|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.

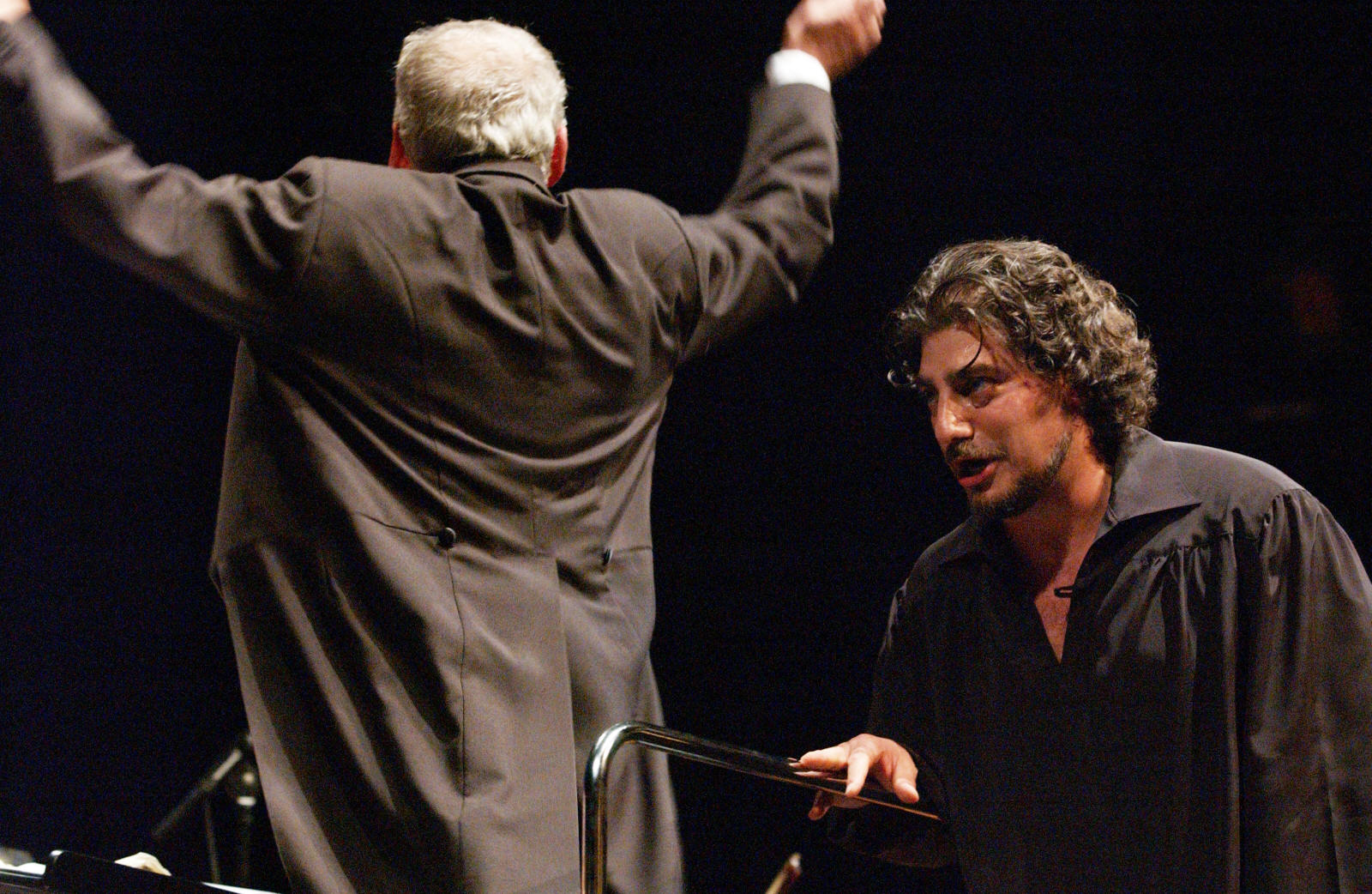

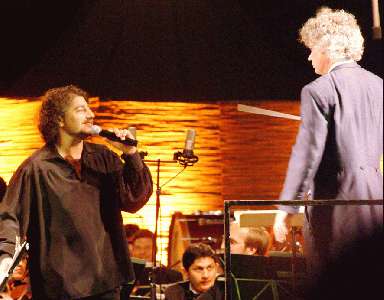

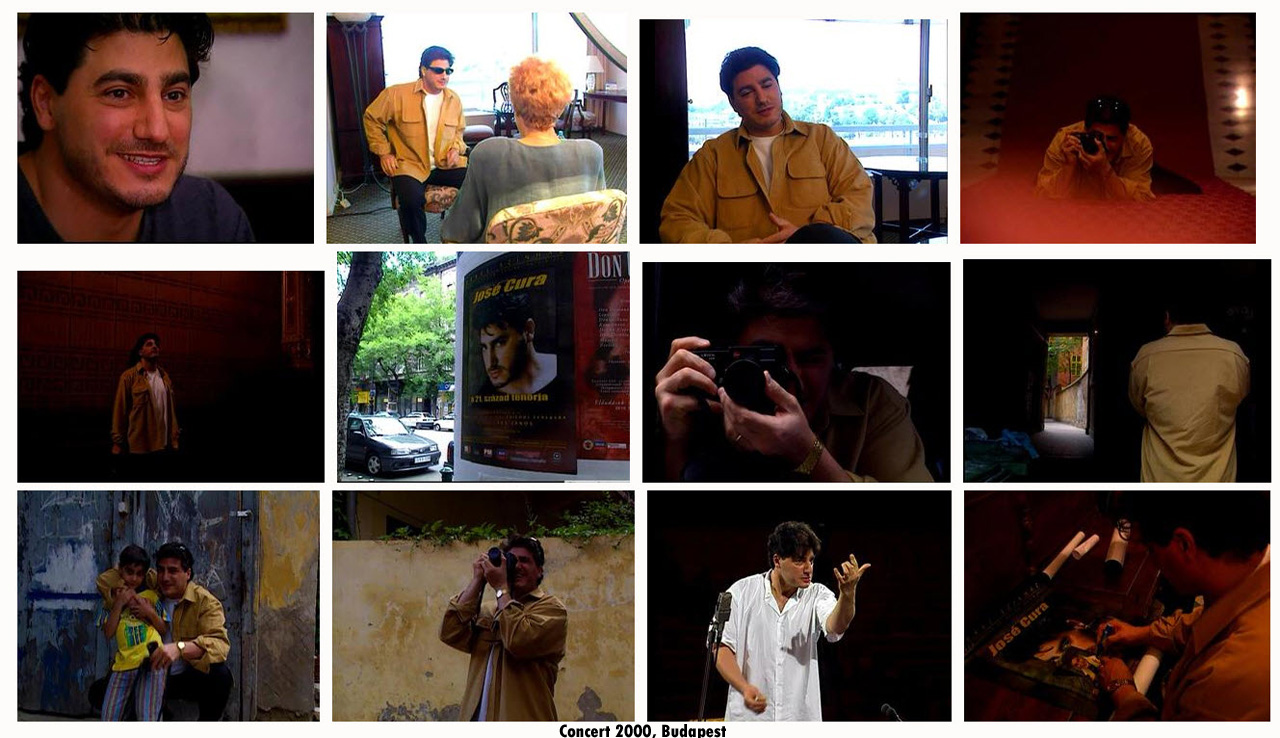

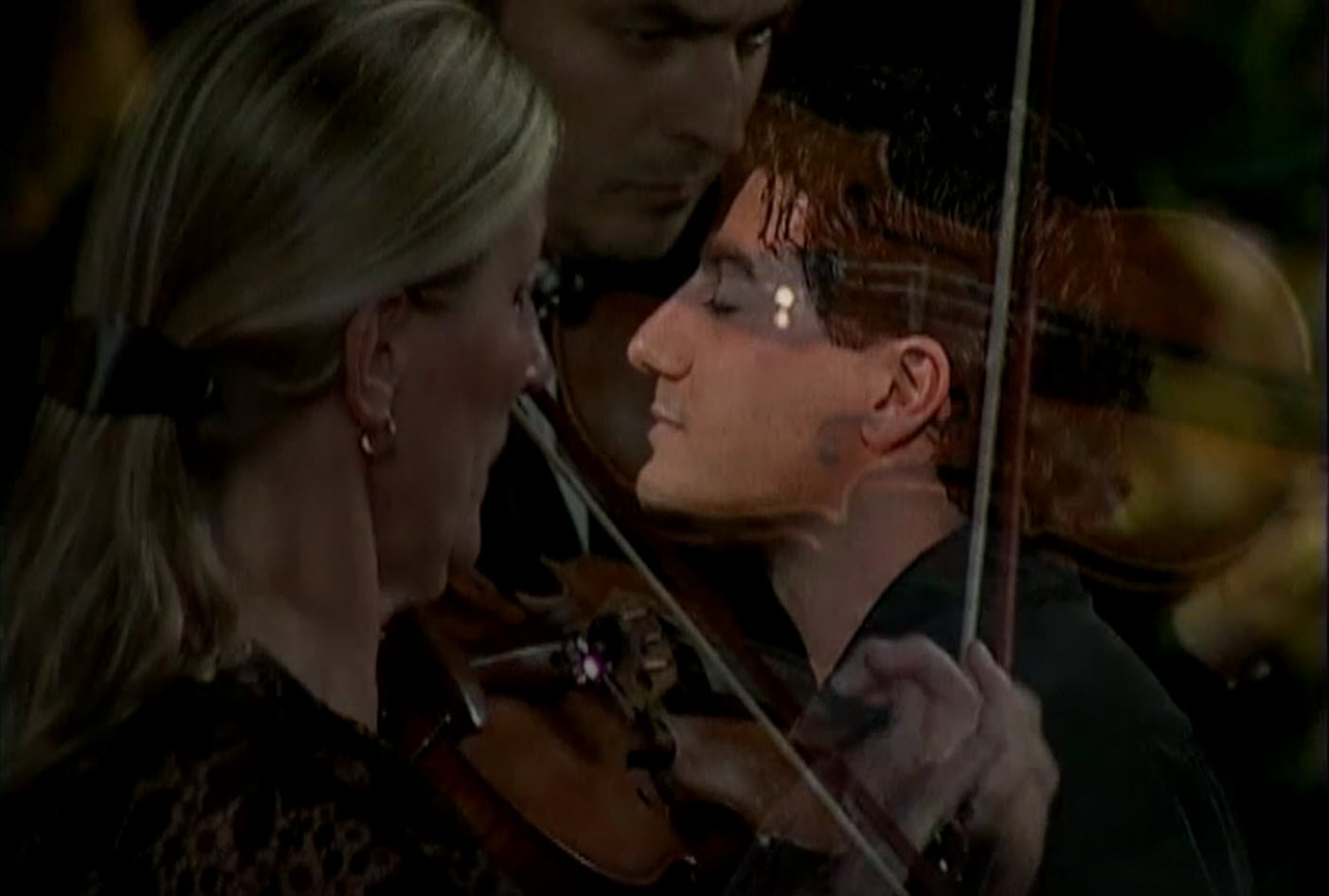

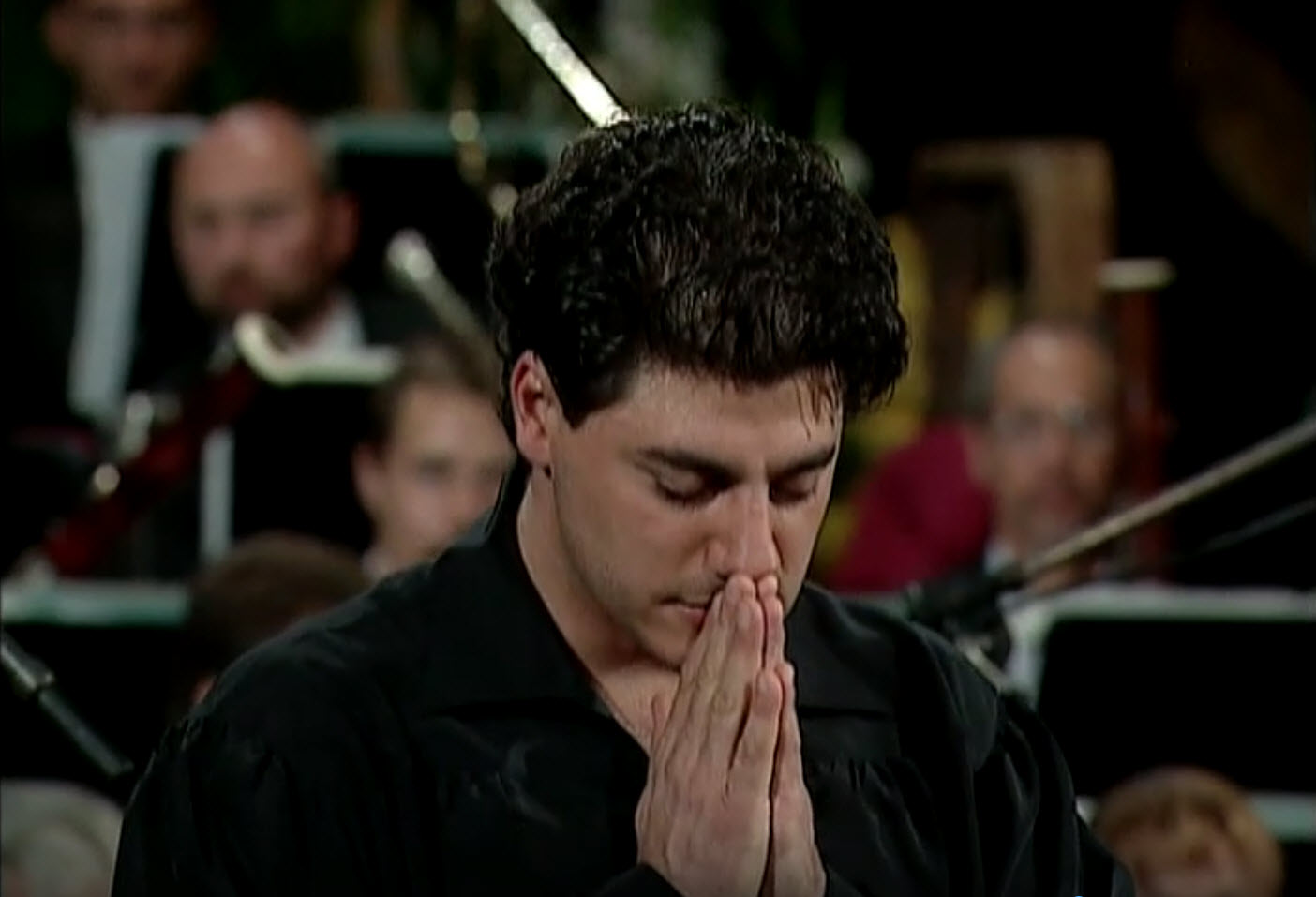

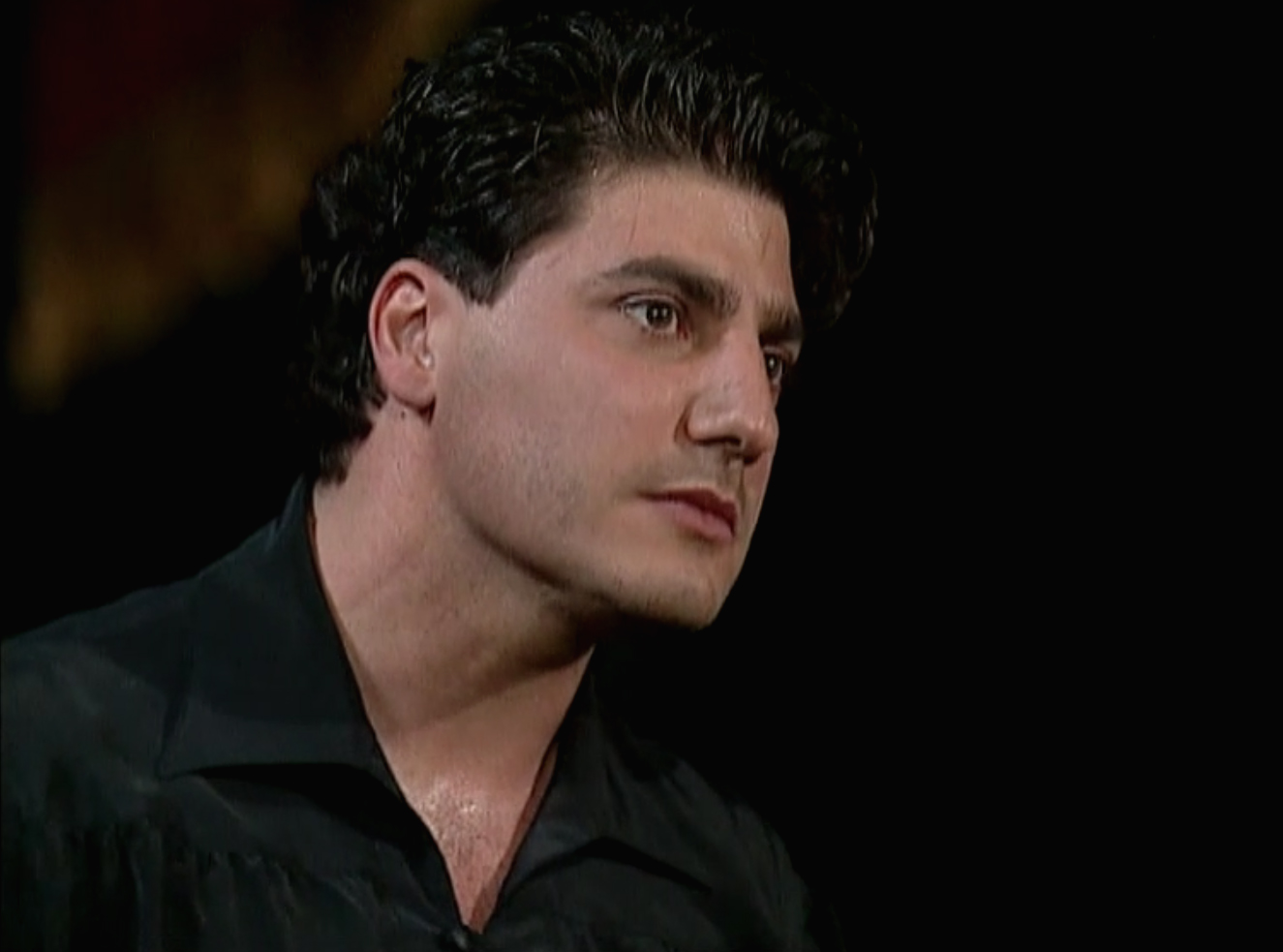

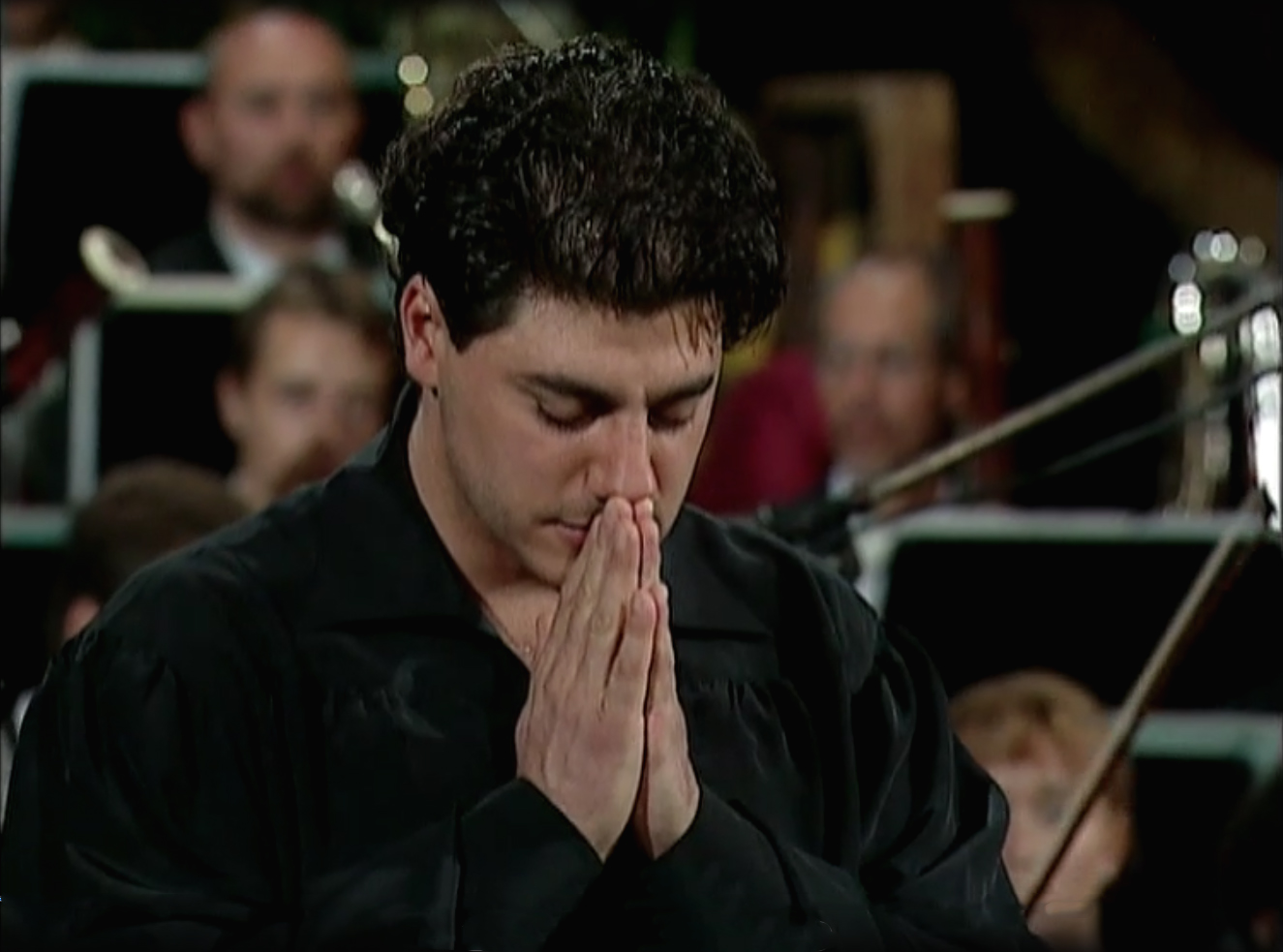

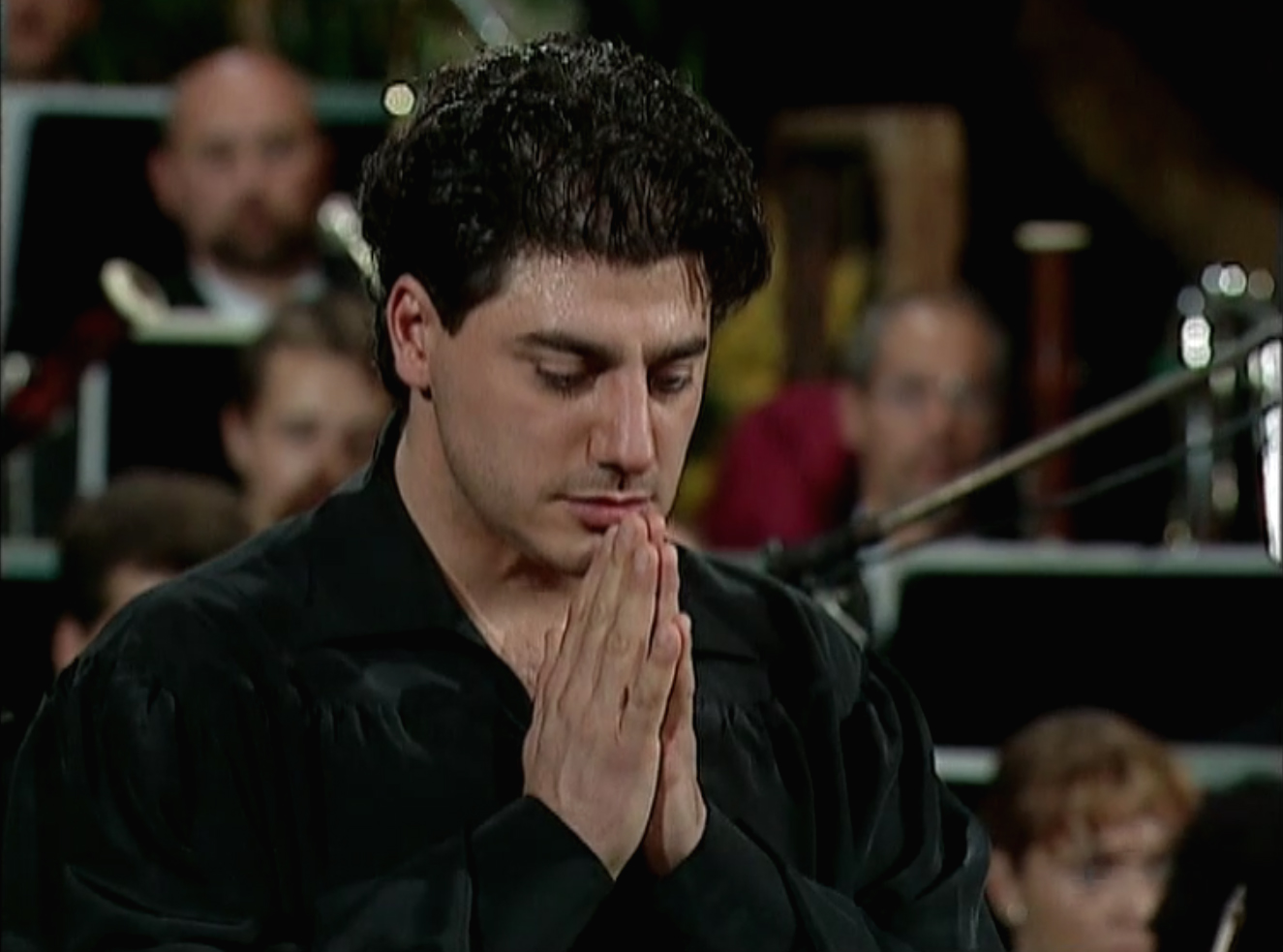

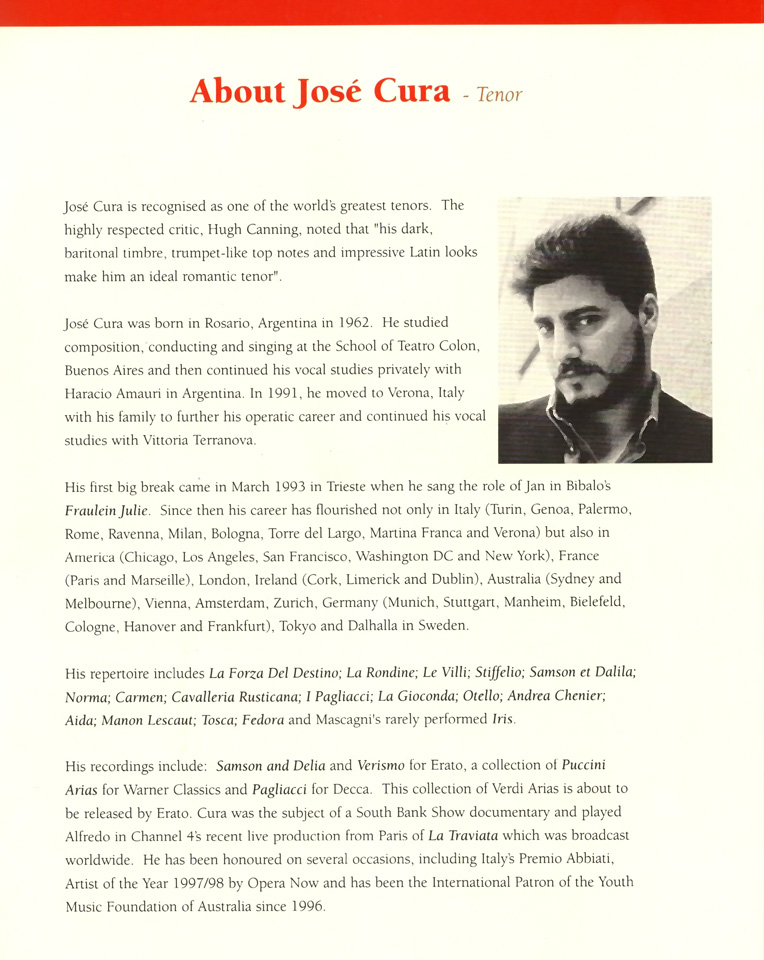

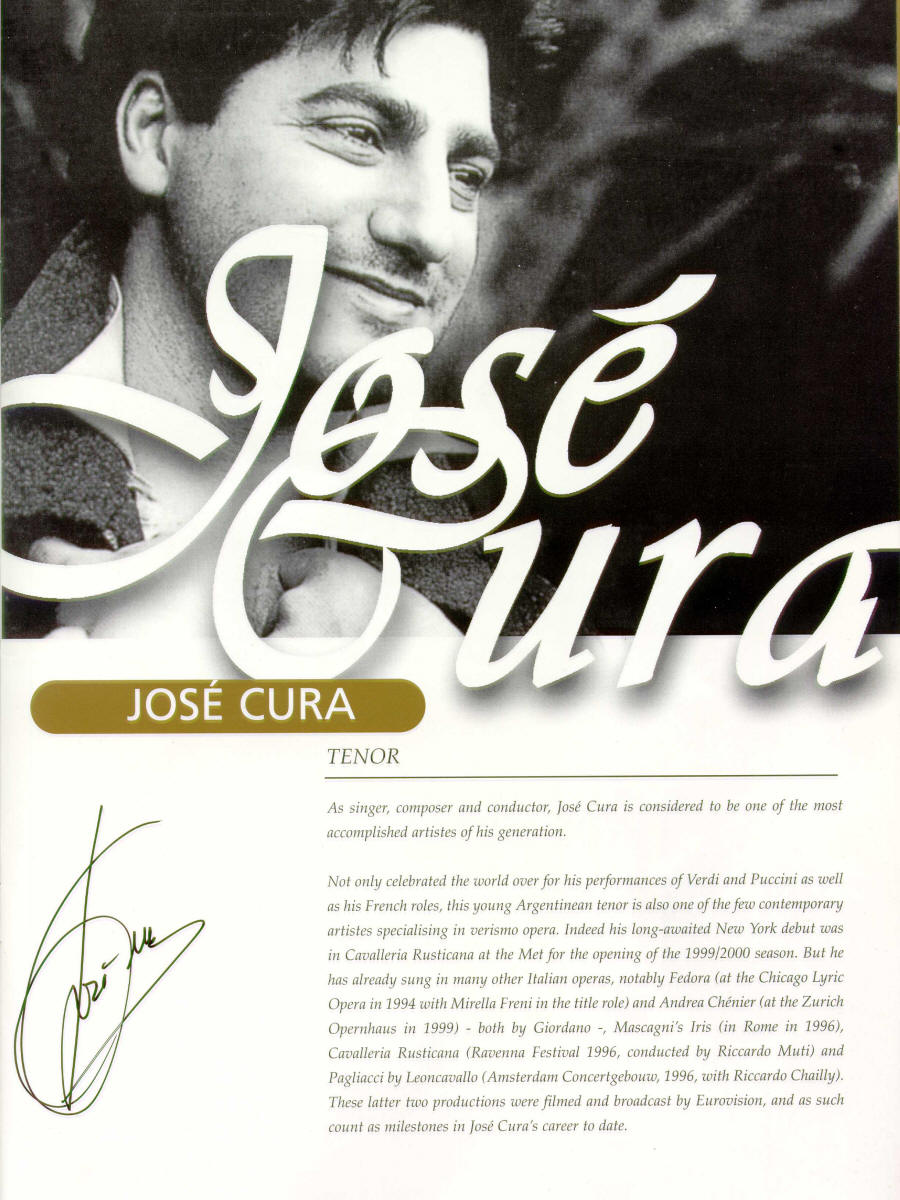

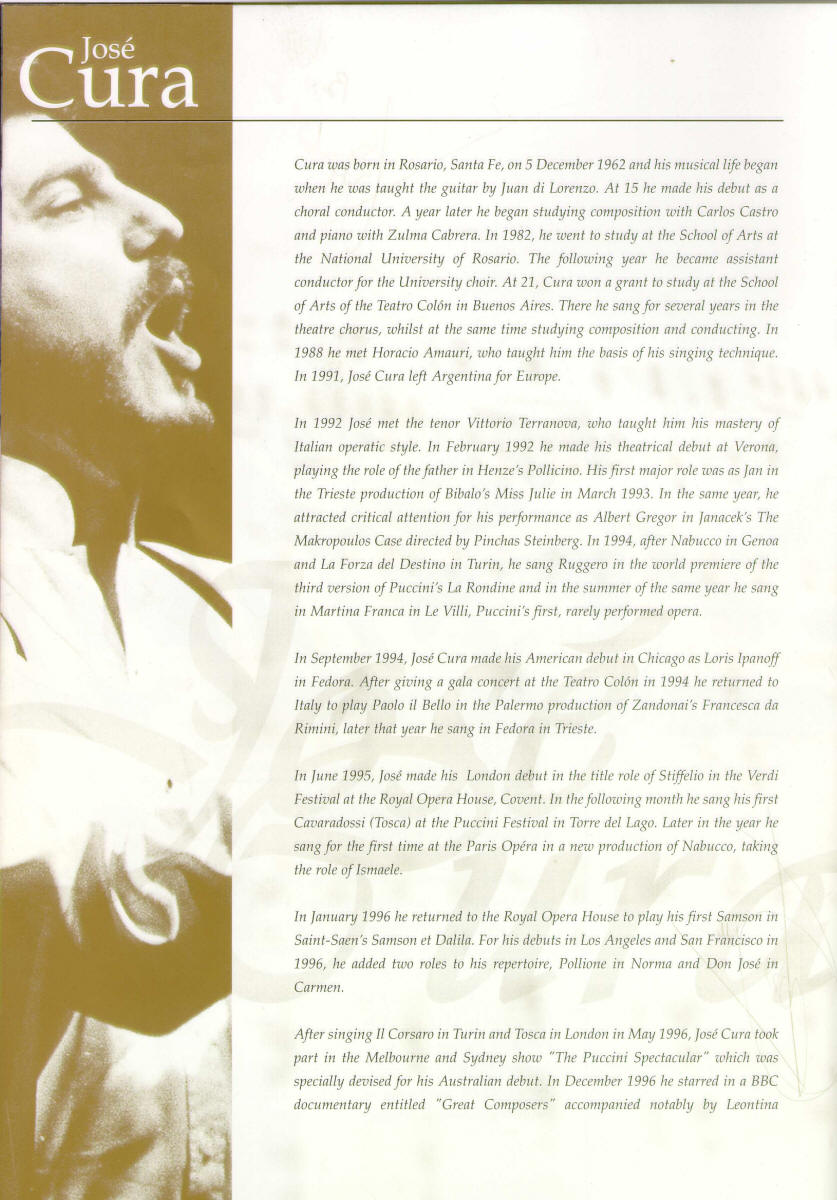

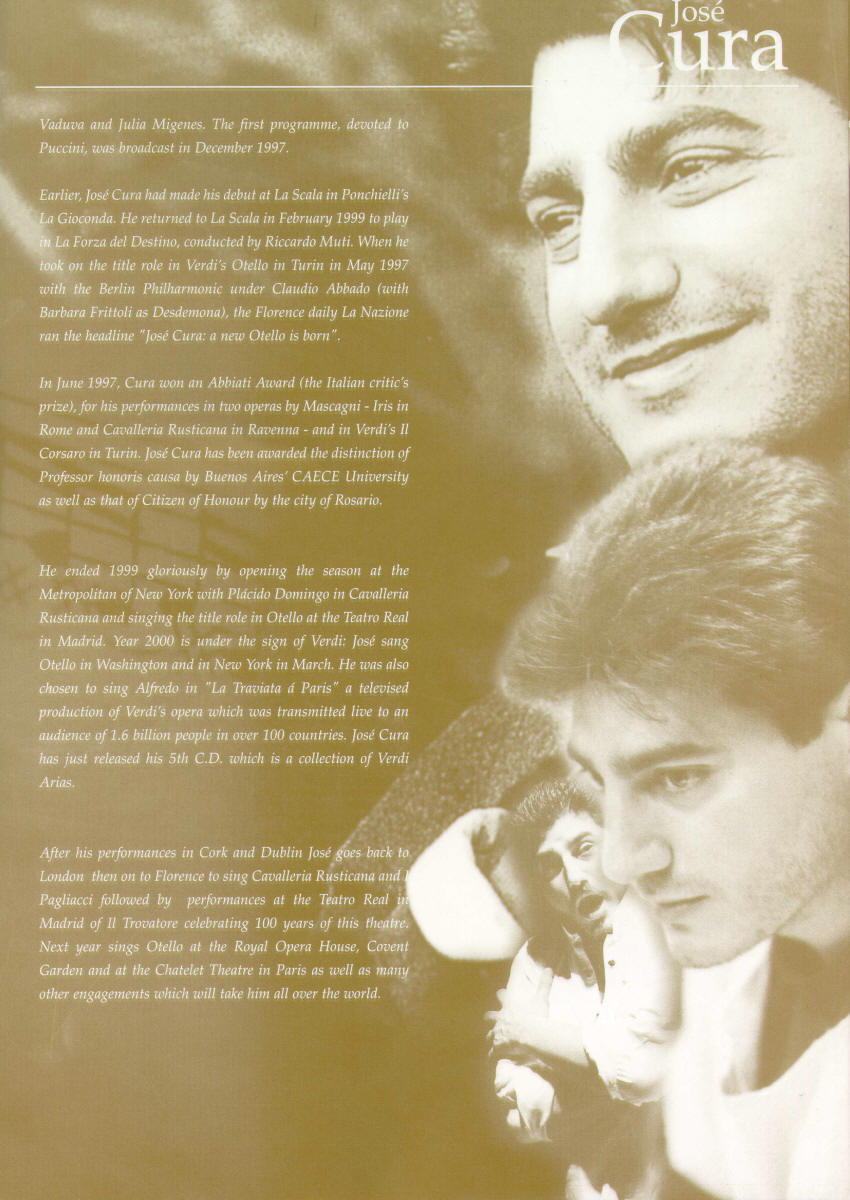

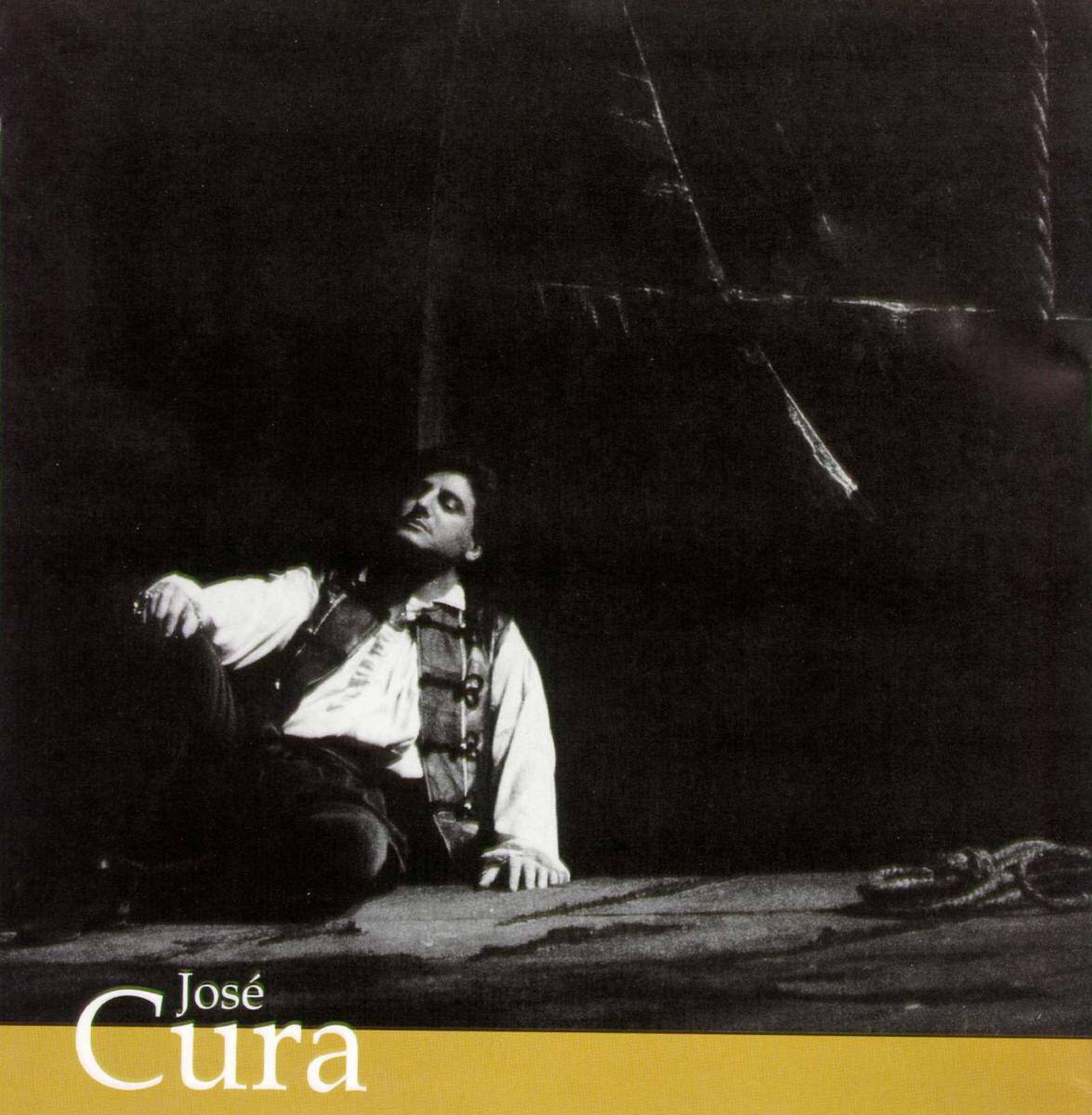

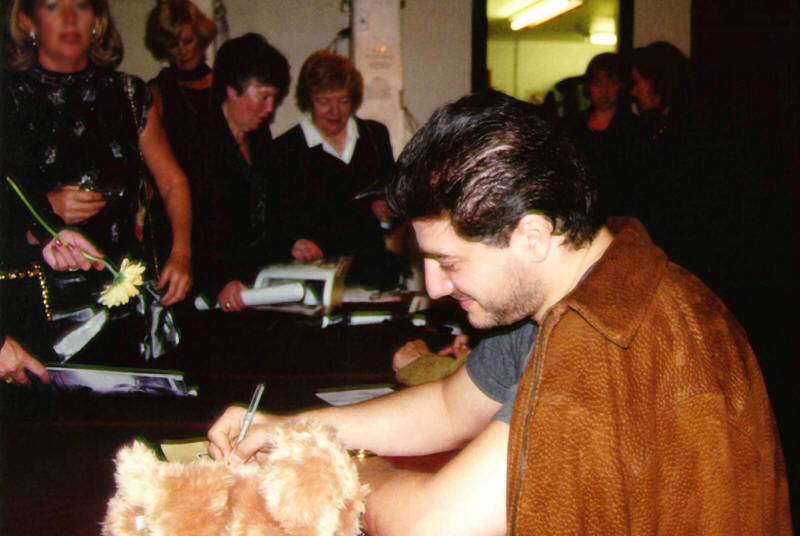

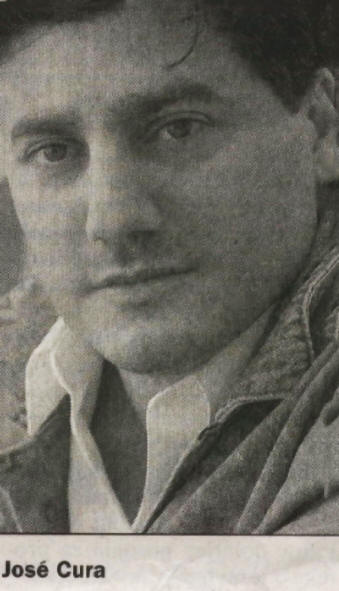

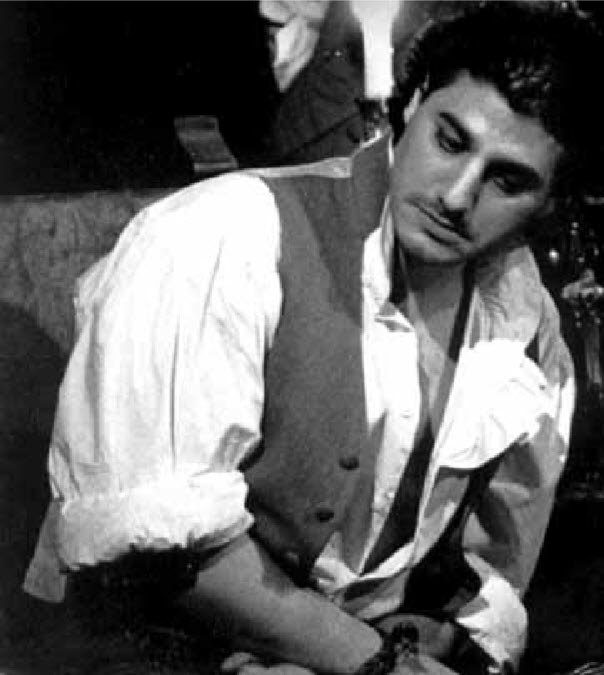

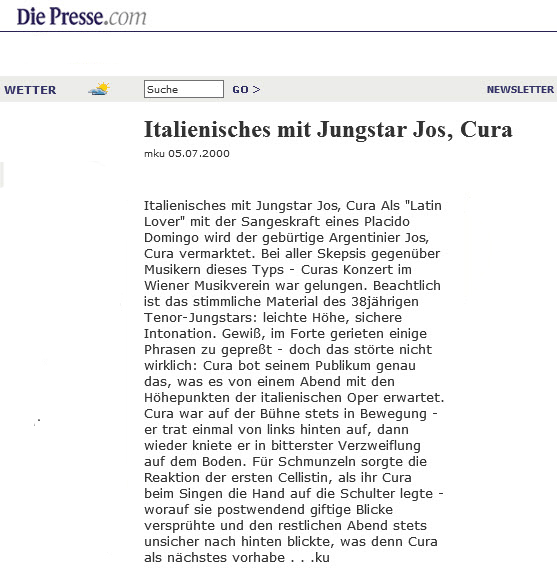

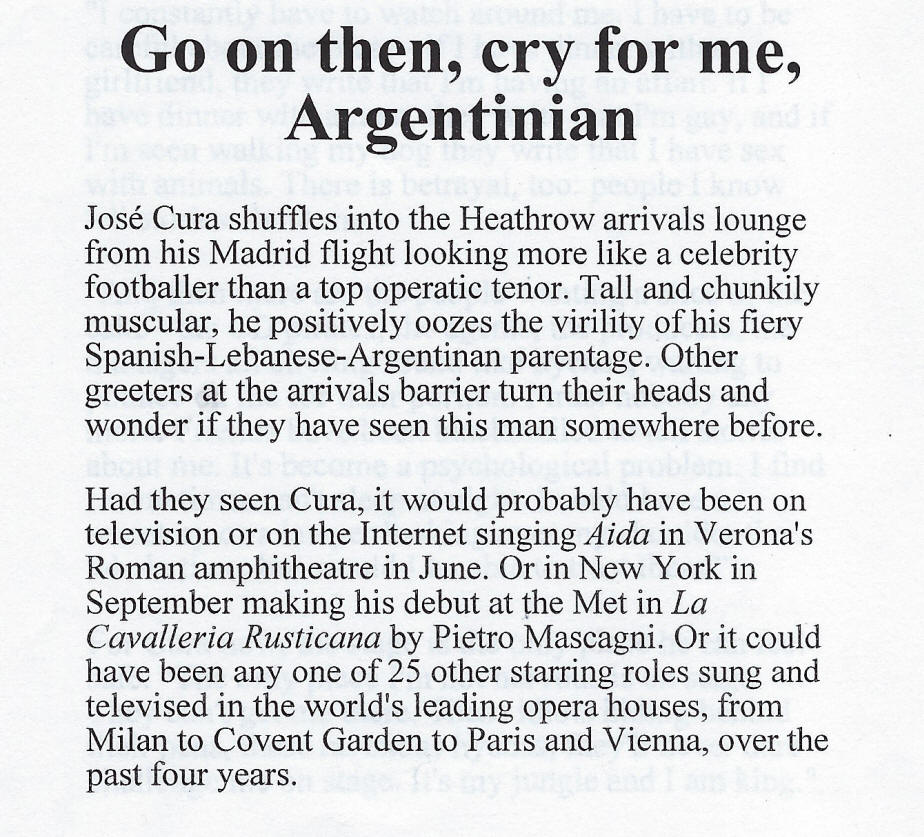

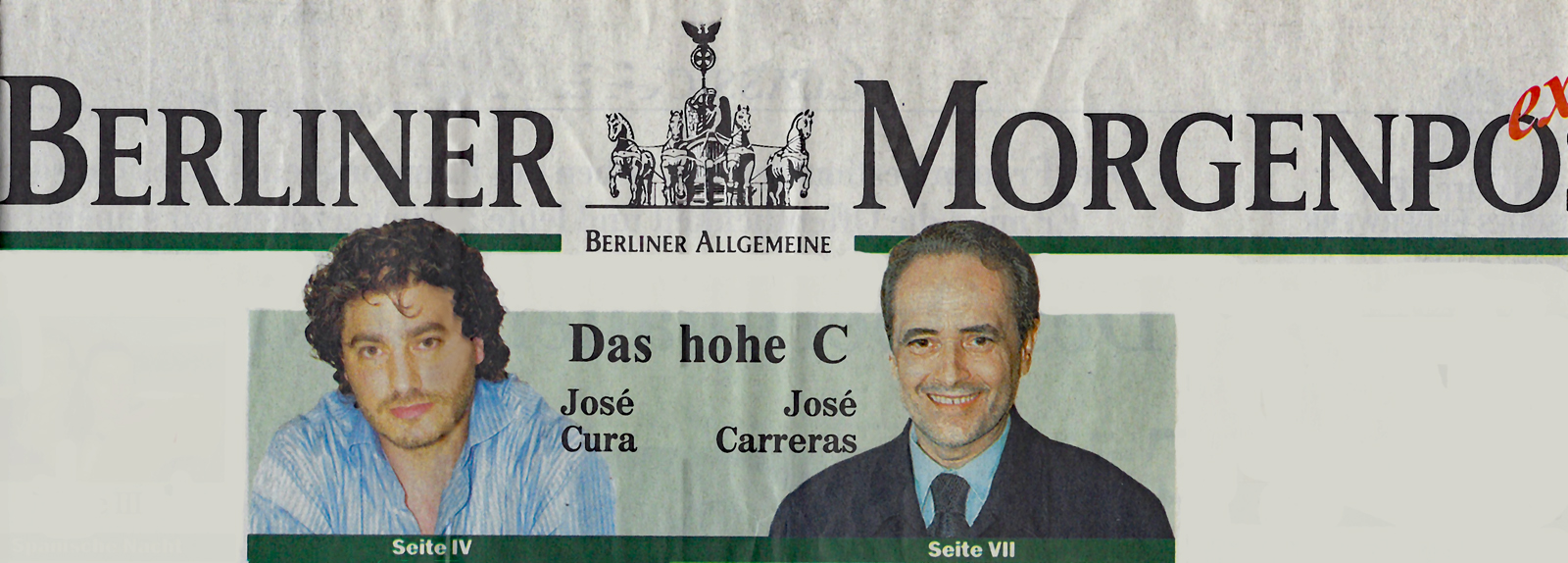

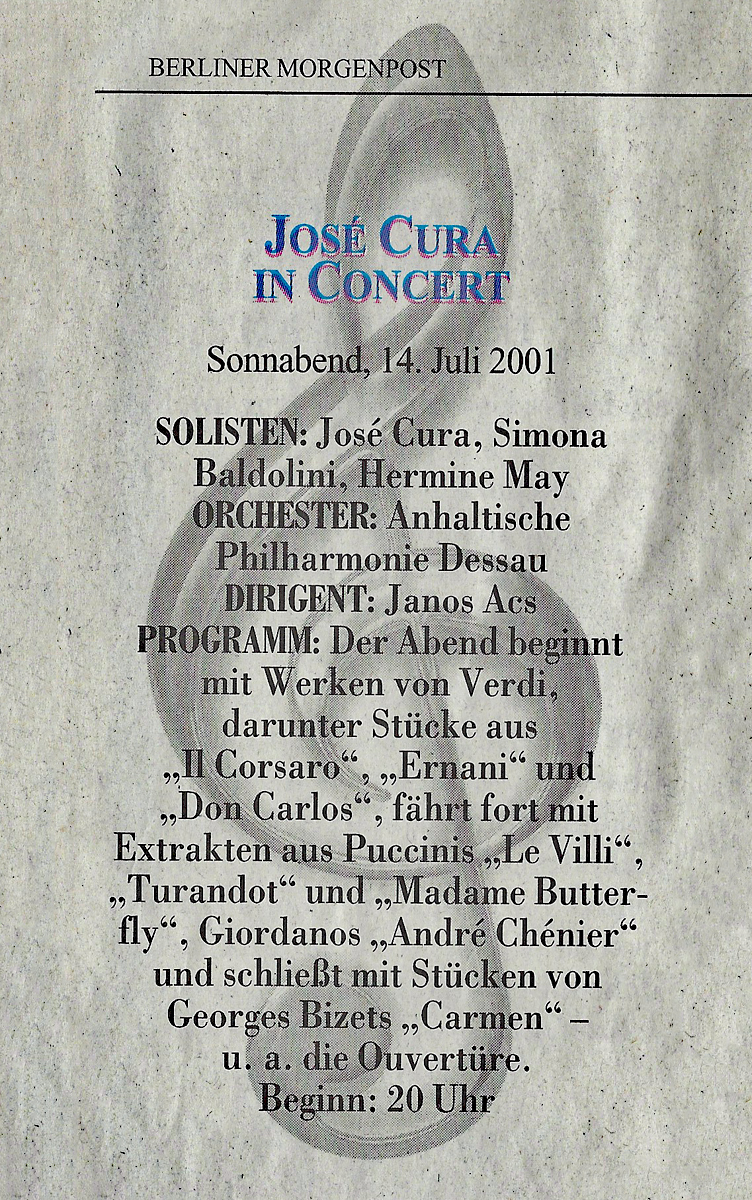

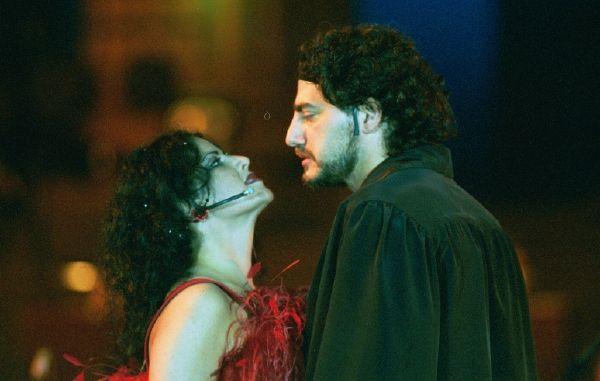

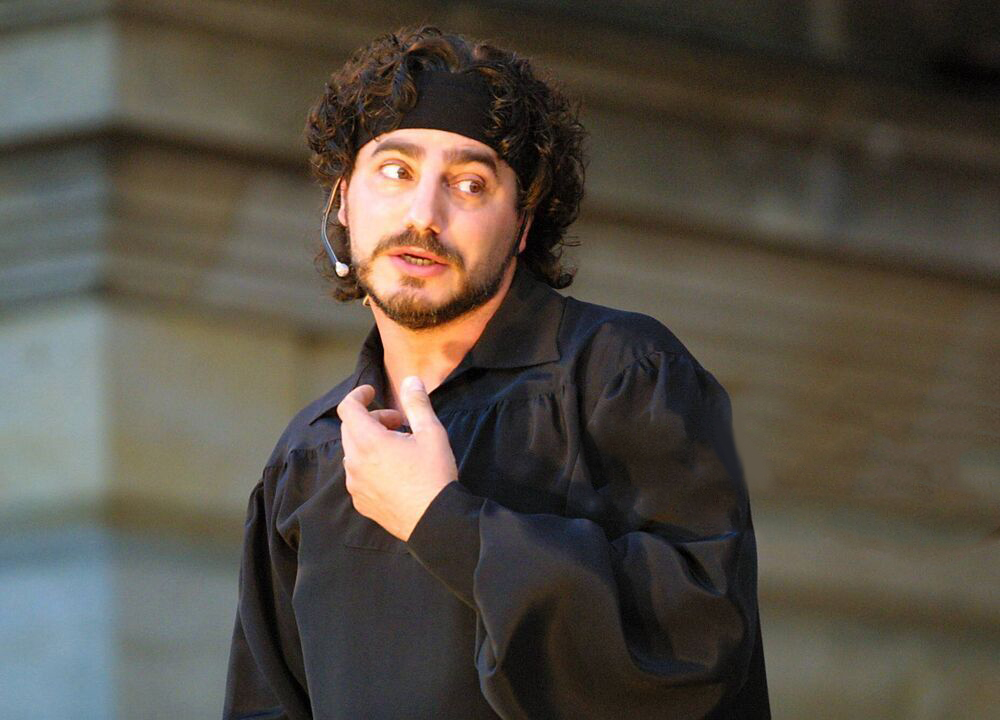

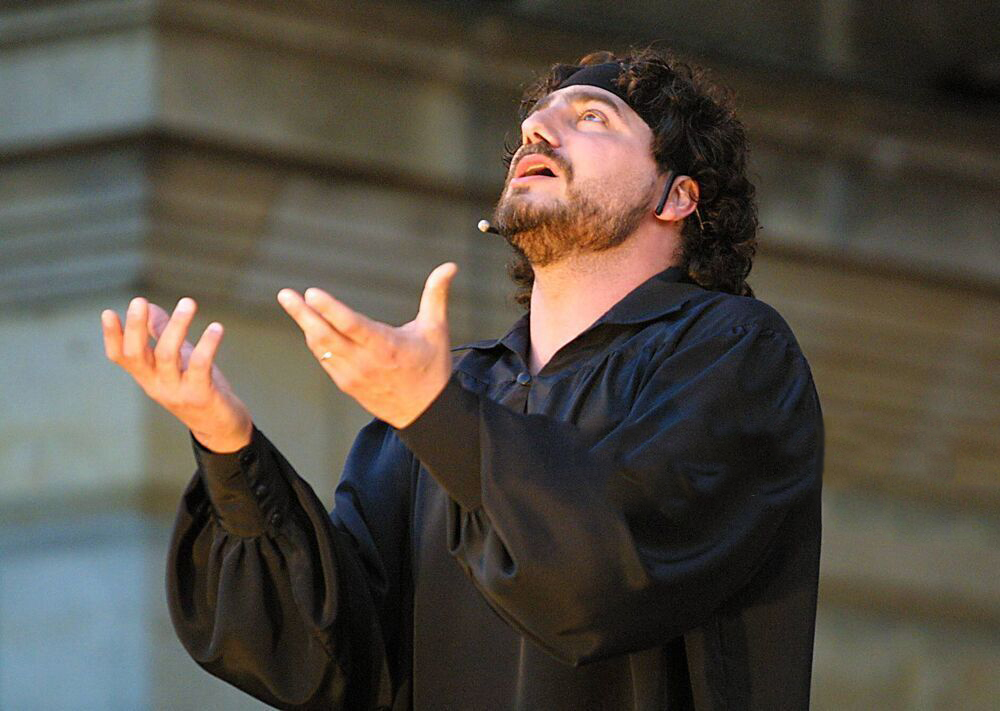

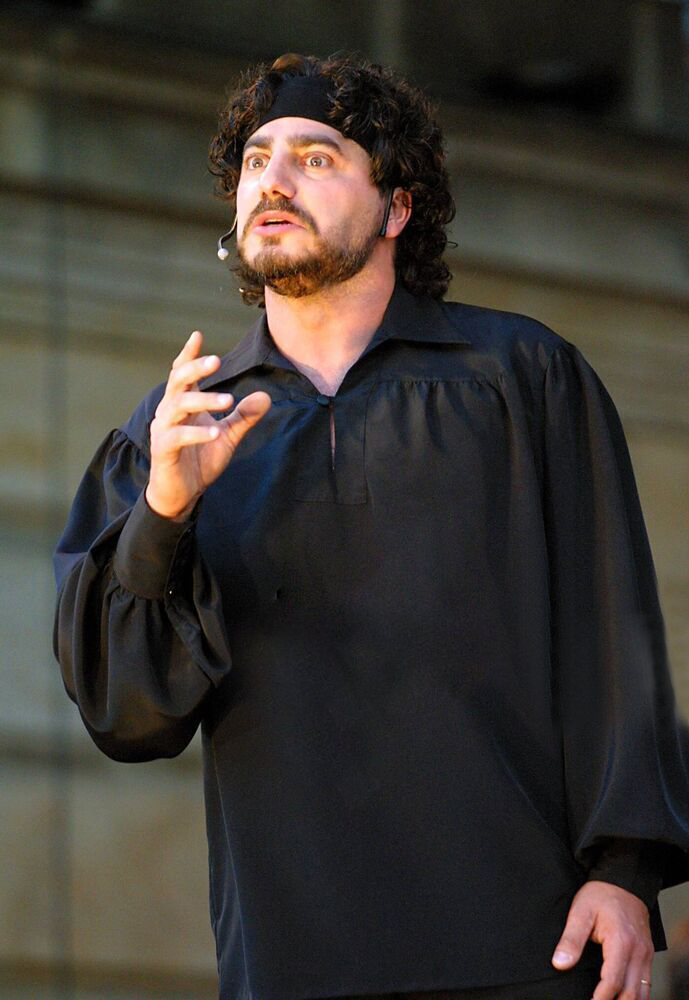

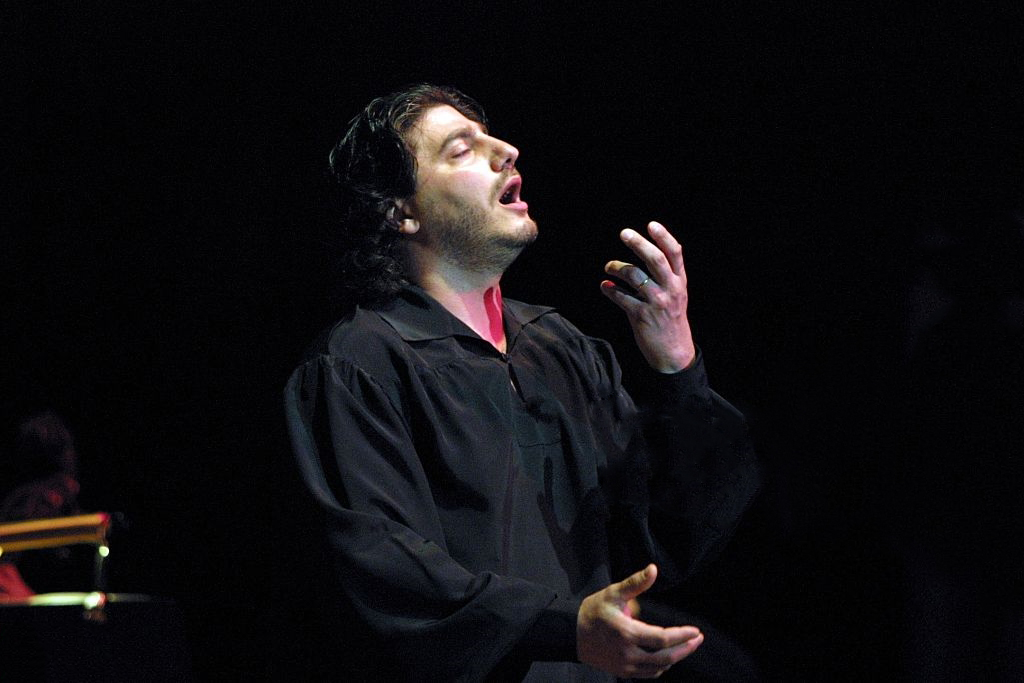

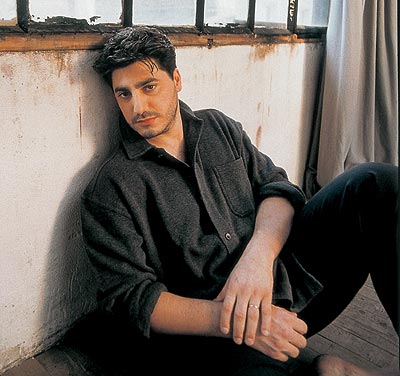

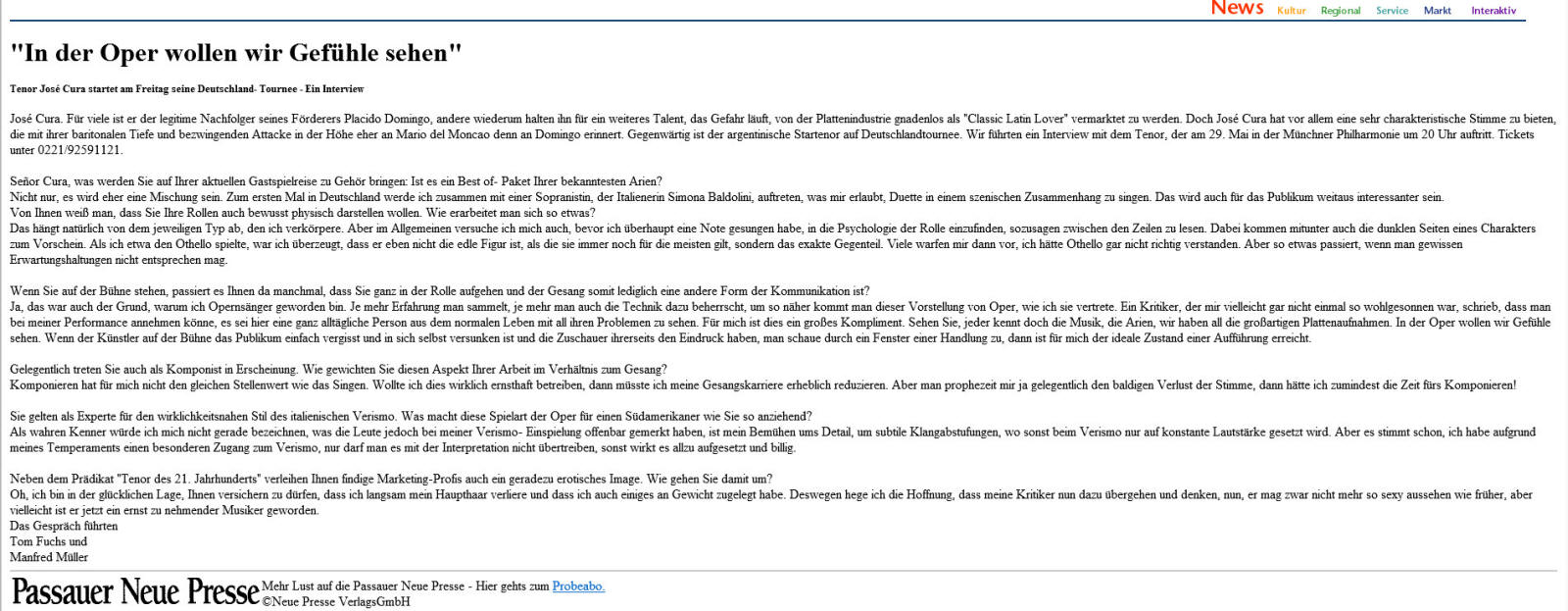

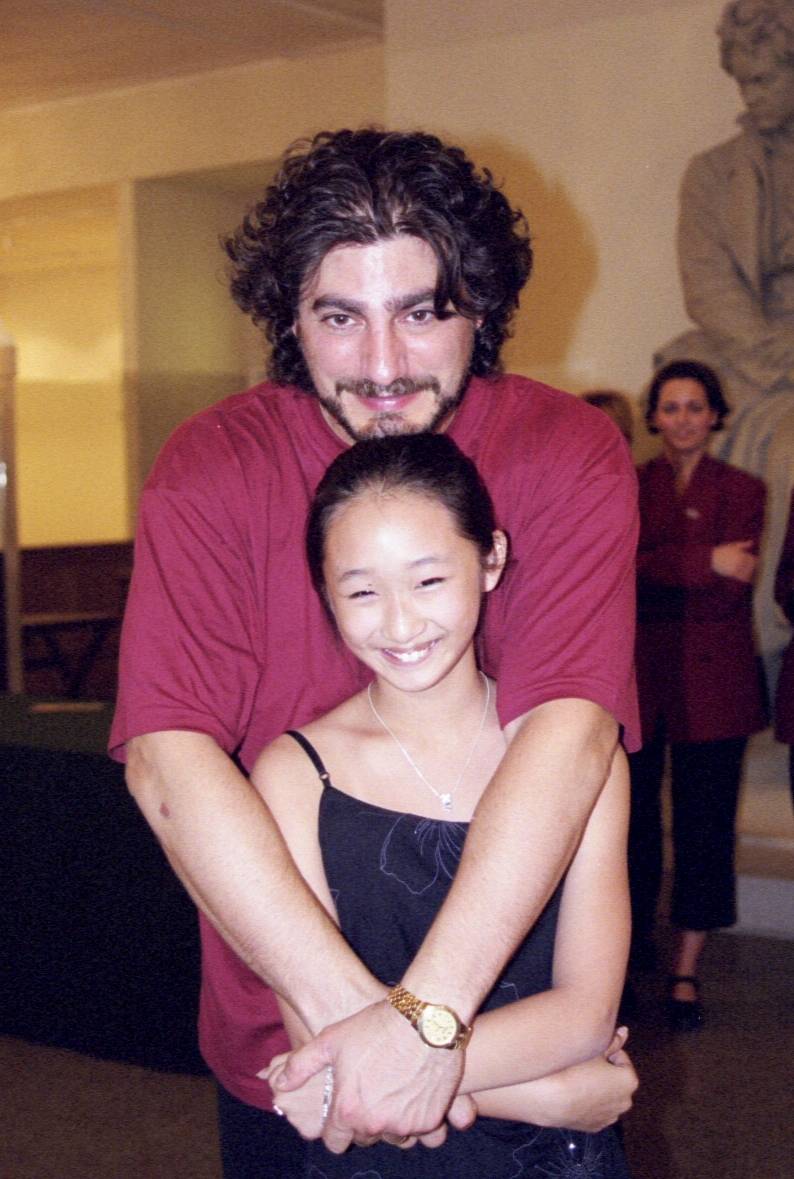

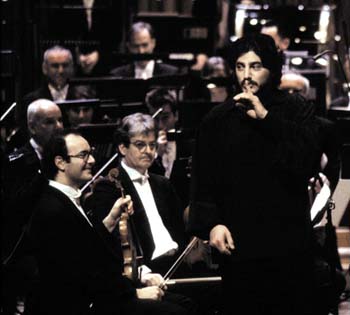

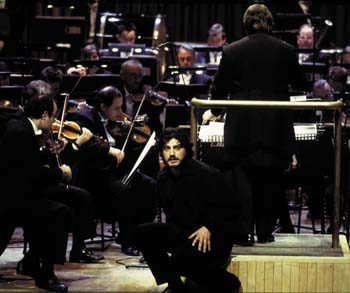

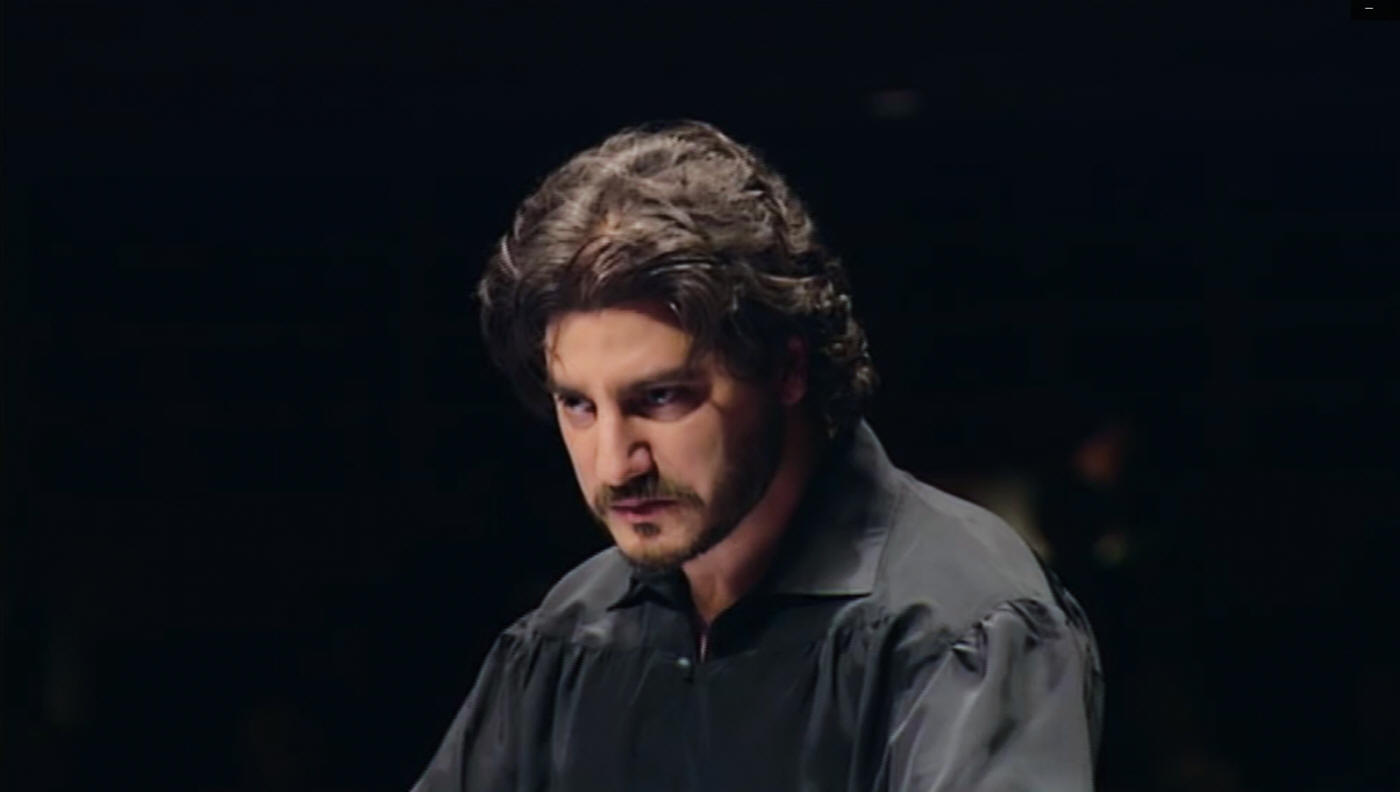

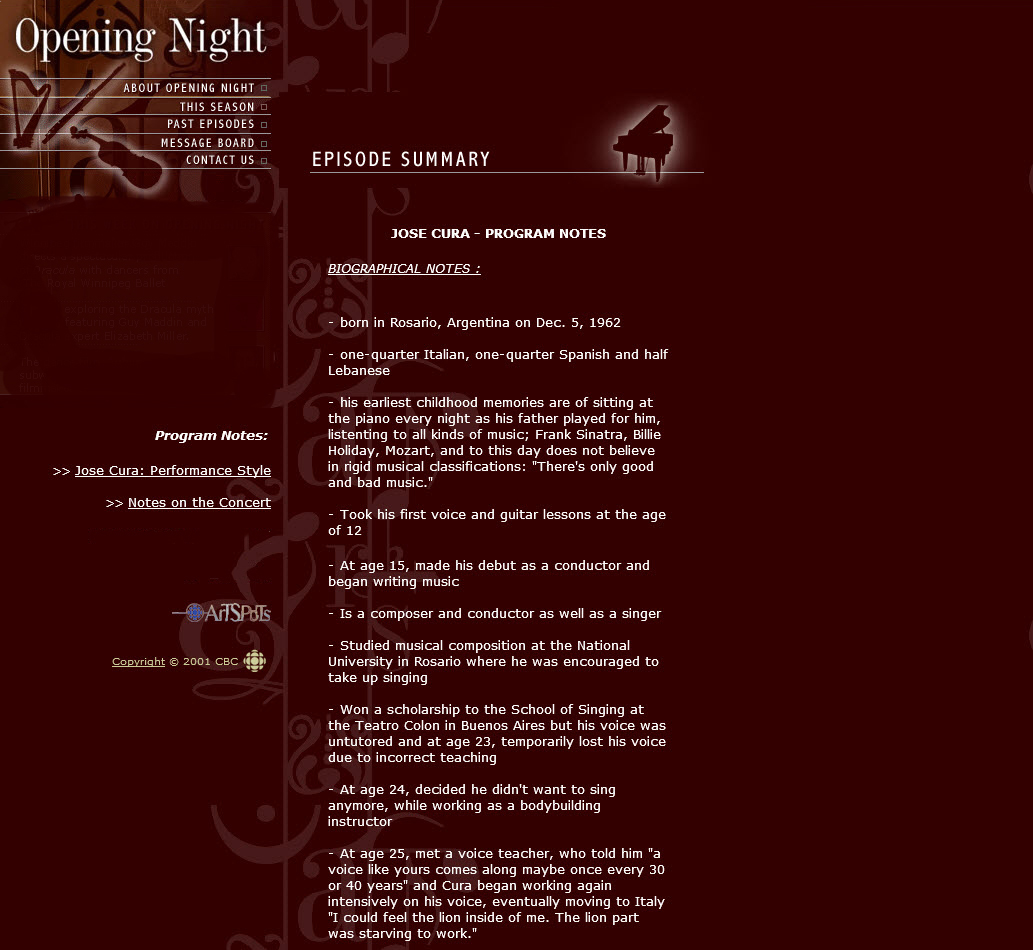

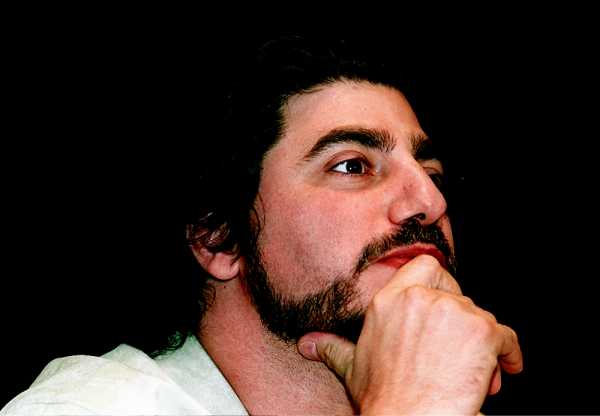

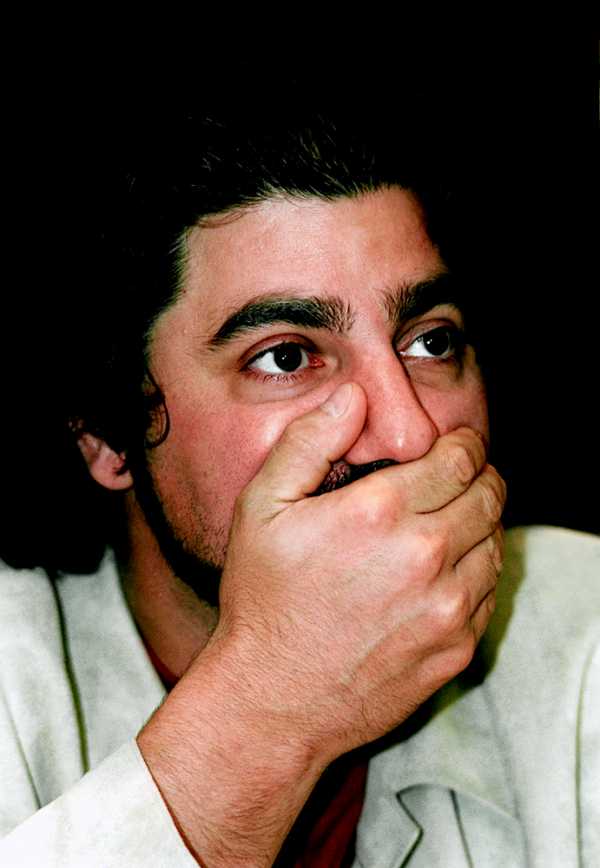

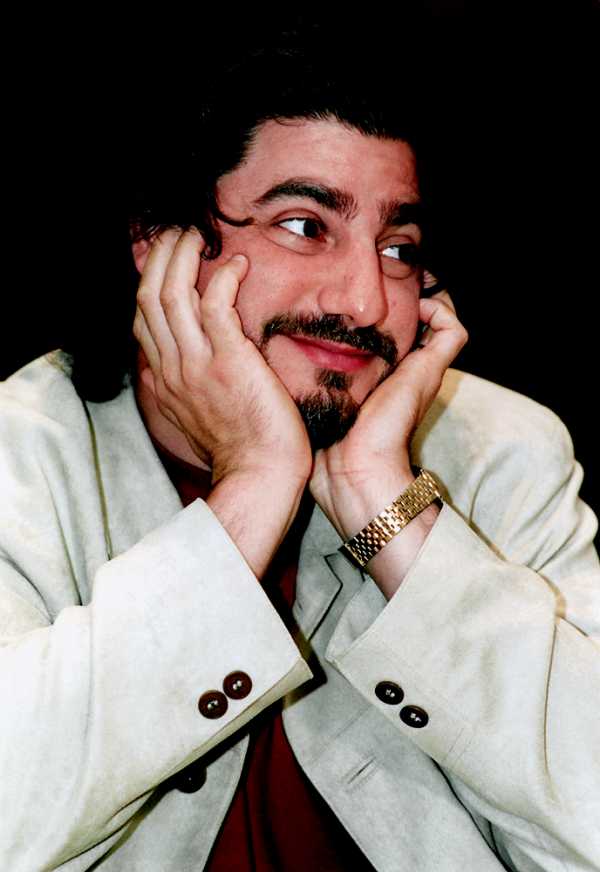

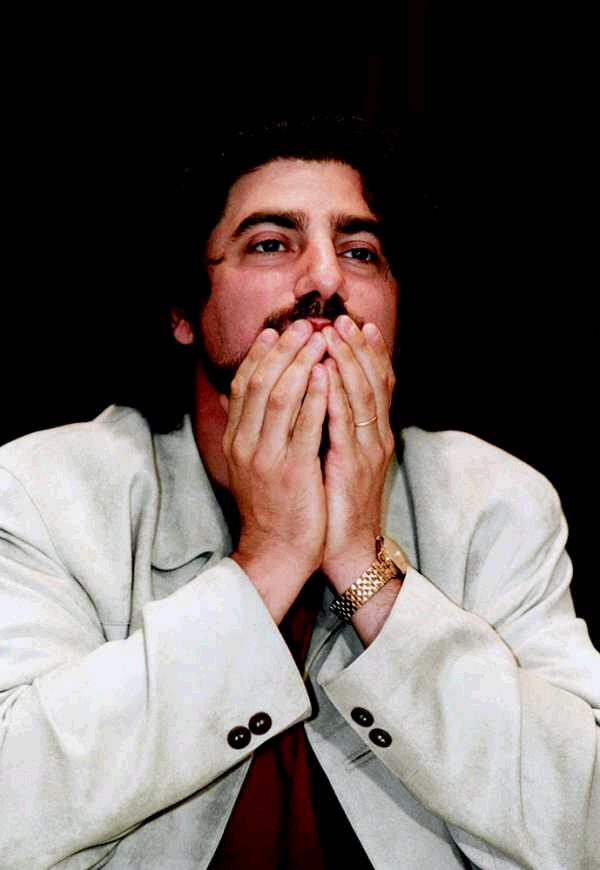

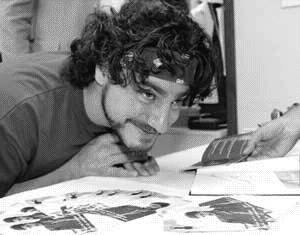

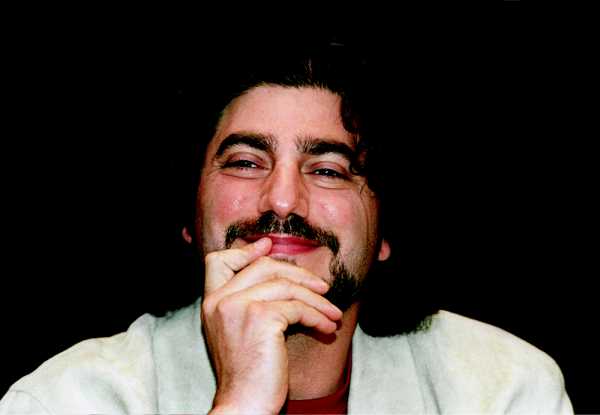

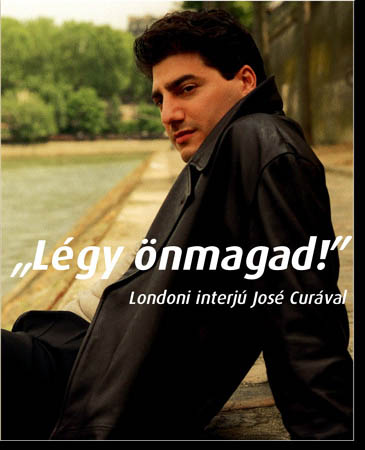

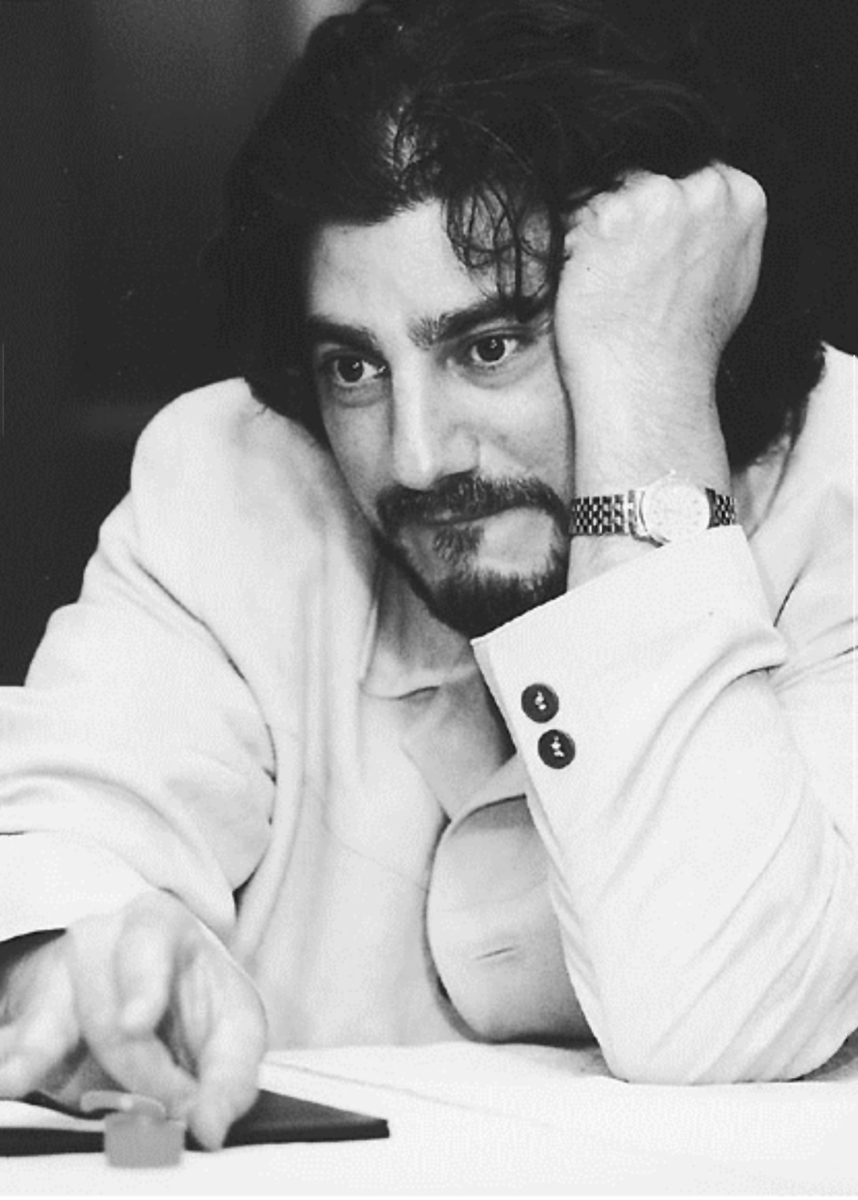

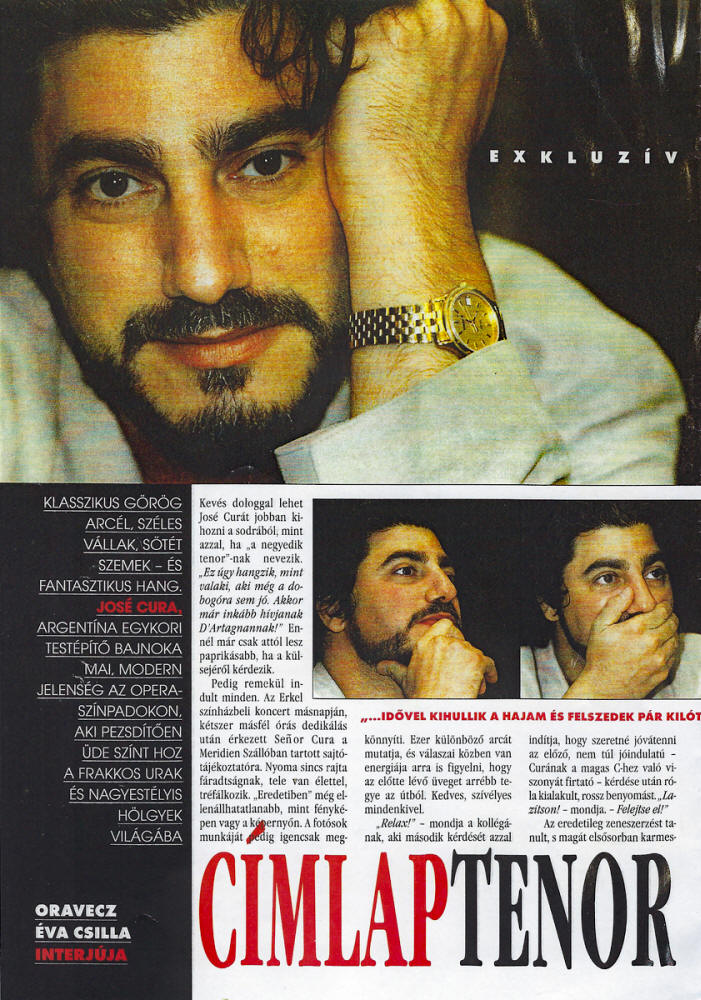

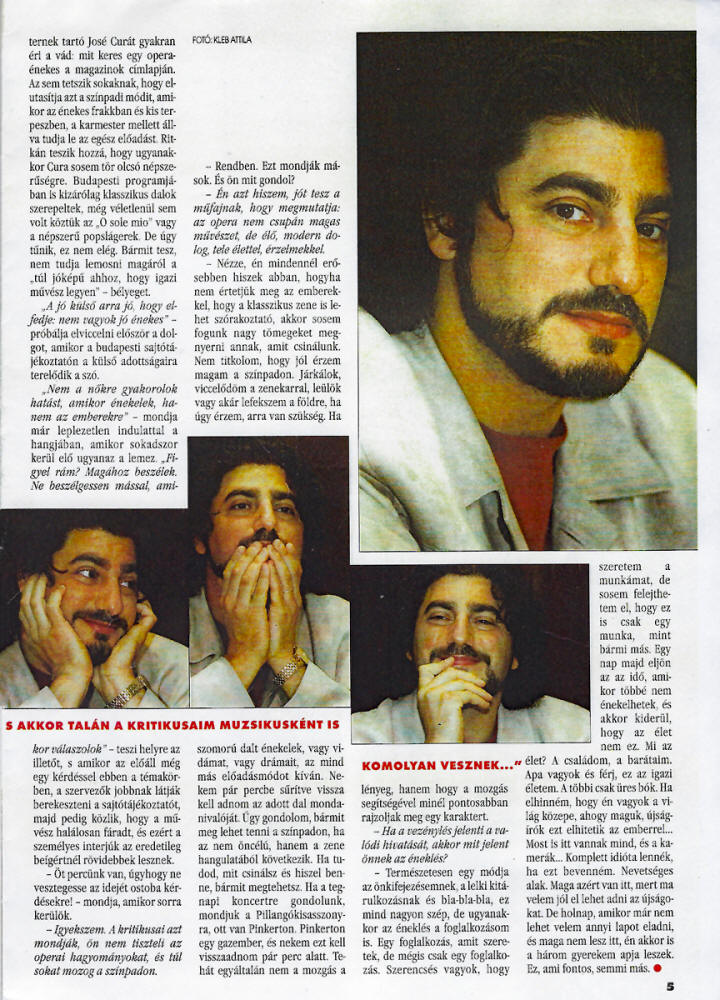

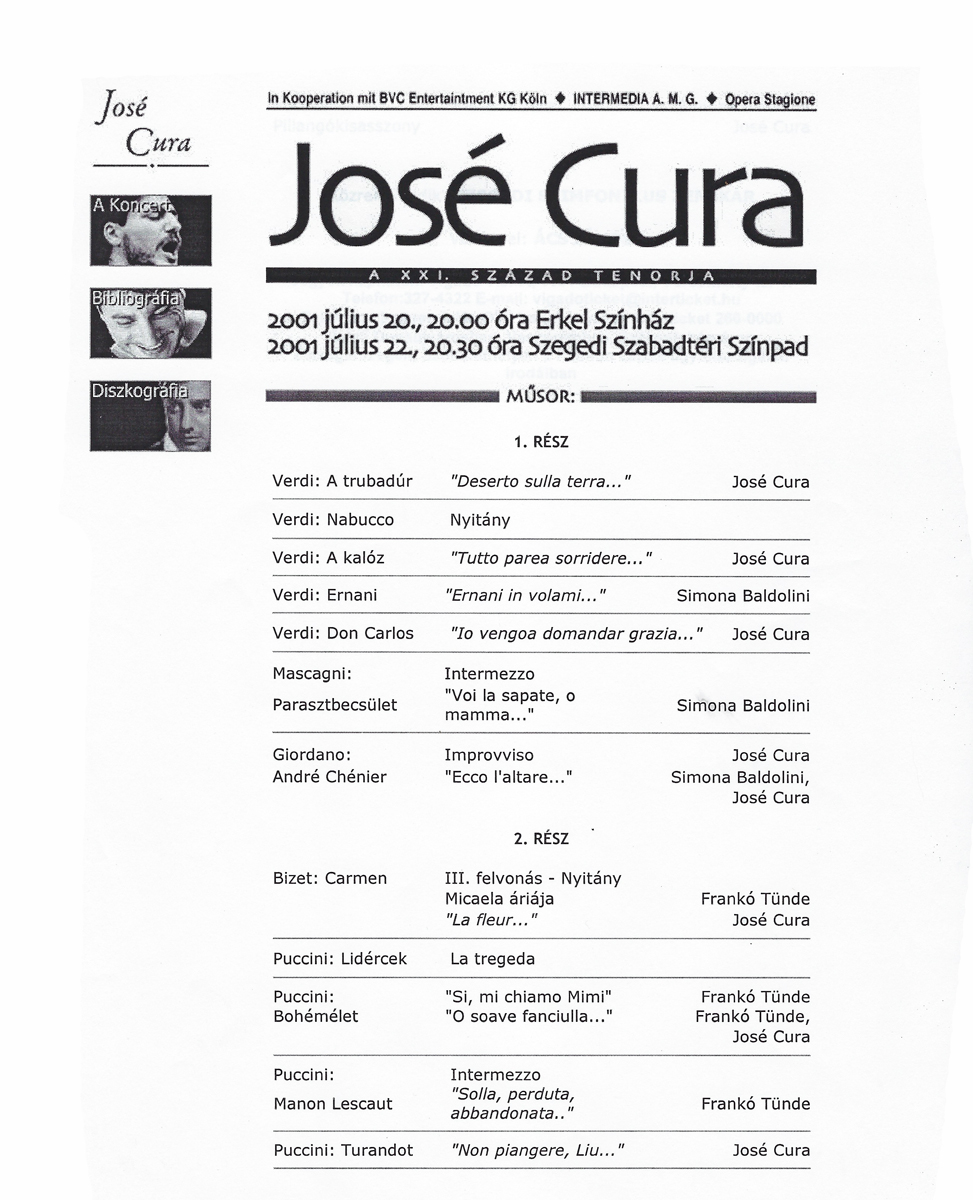

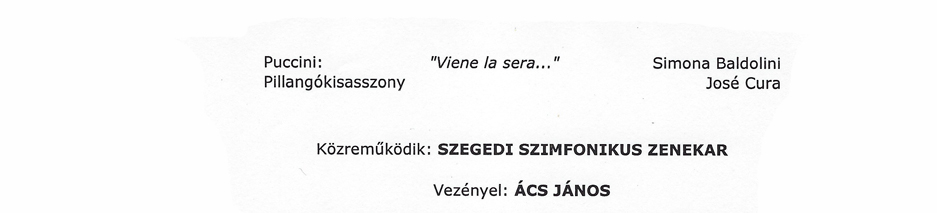

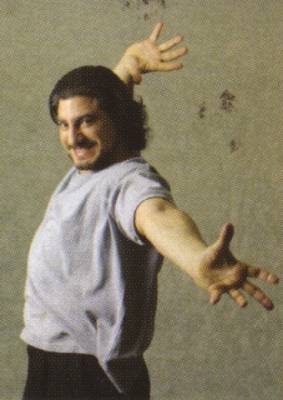

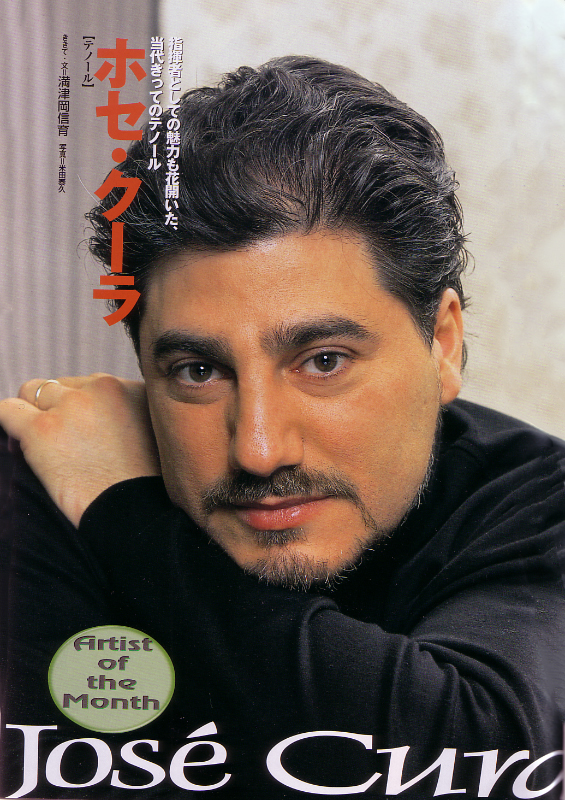

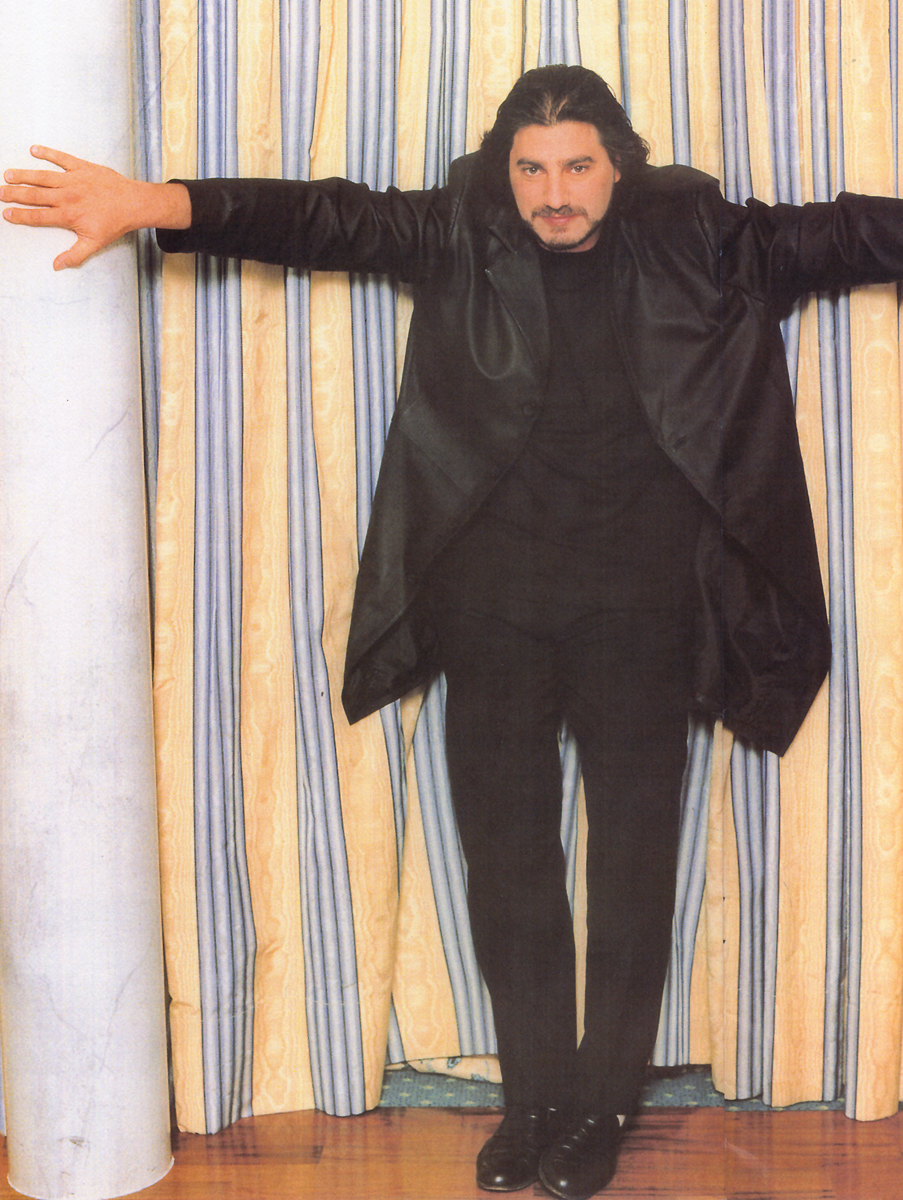

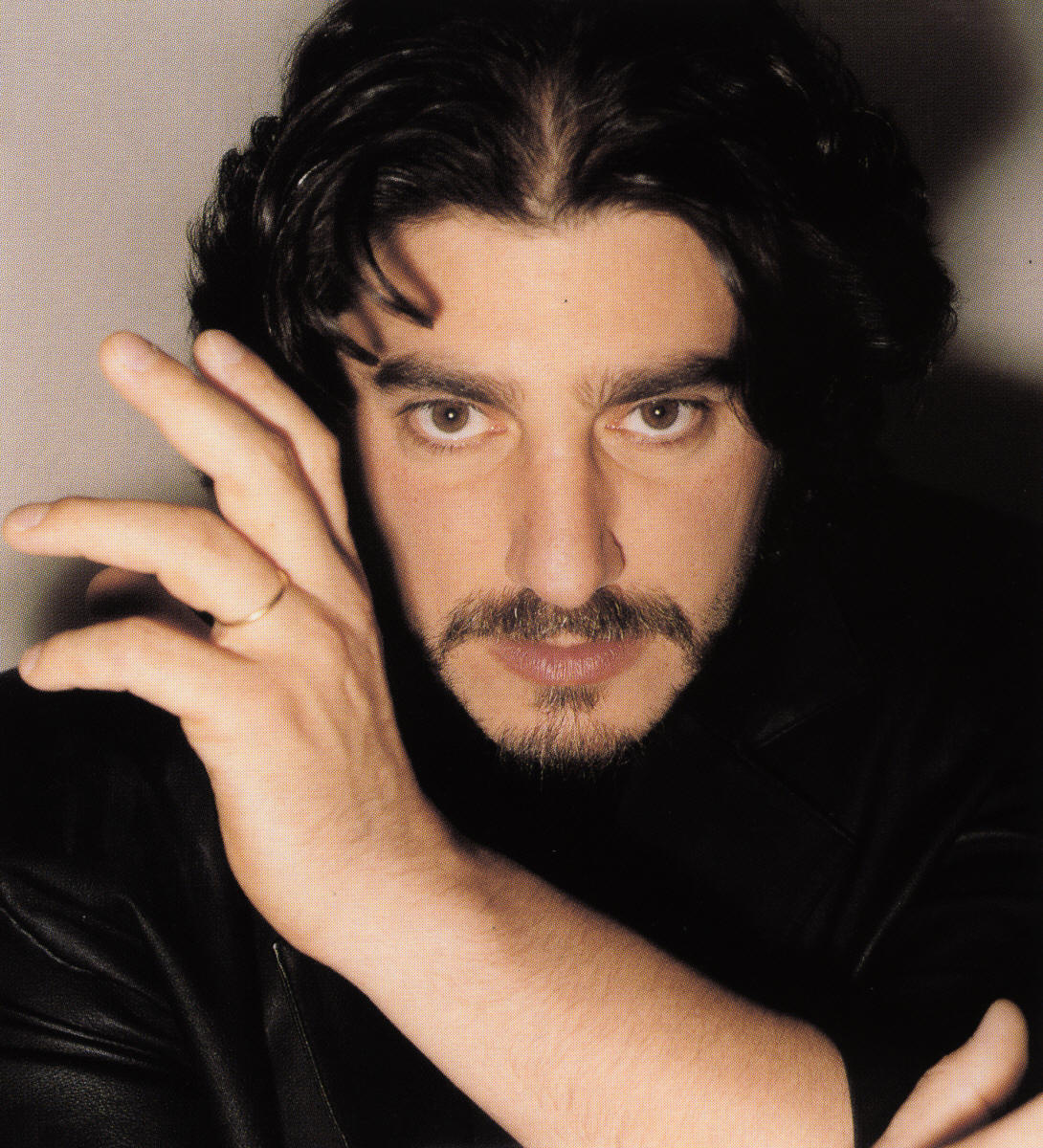

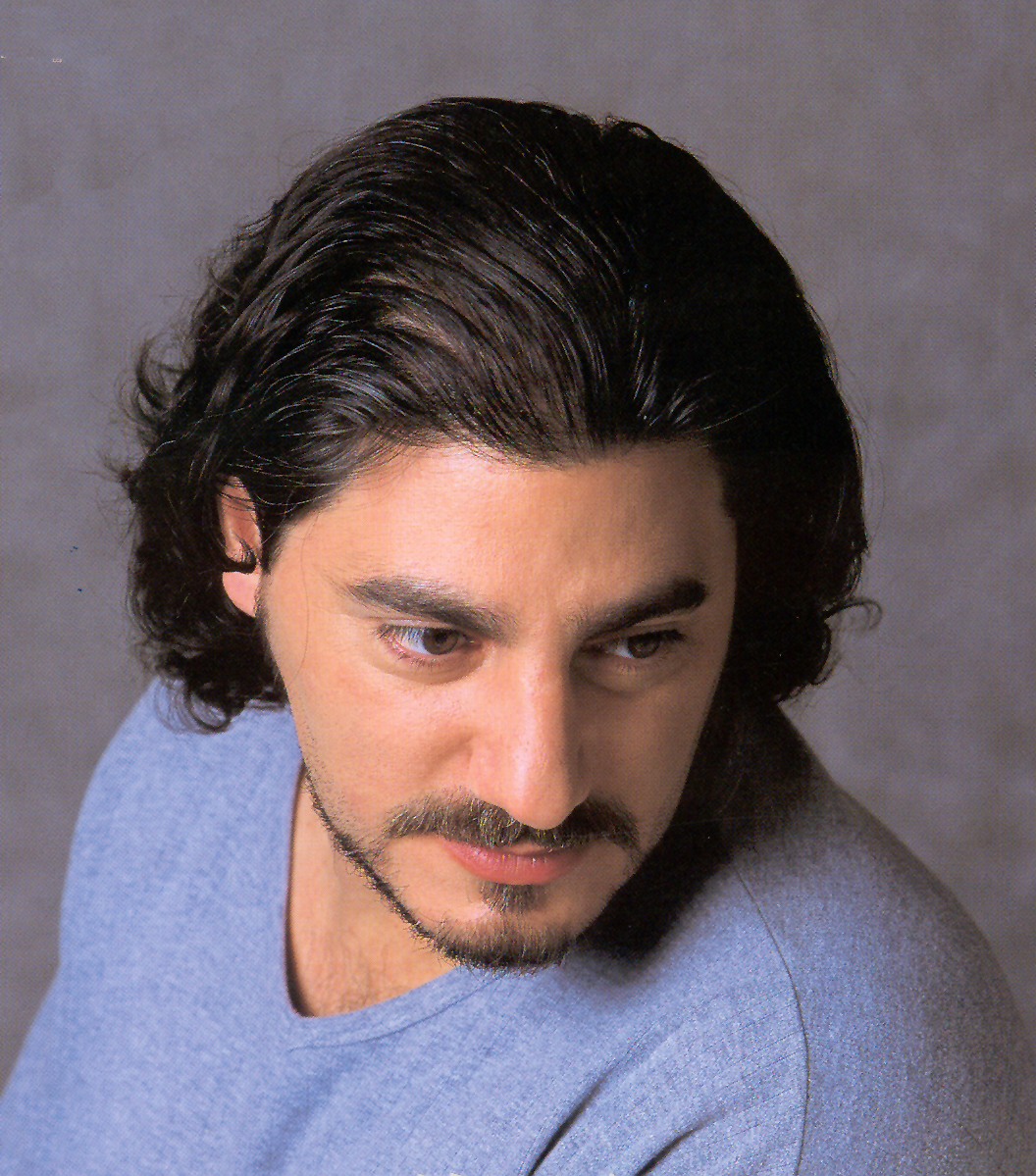

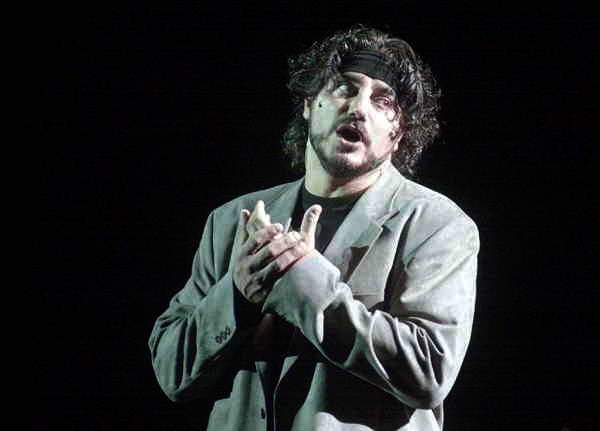

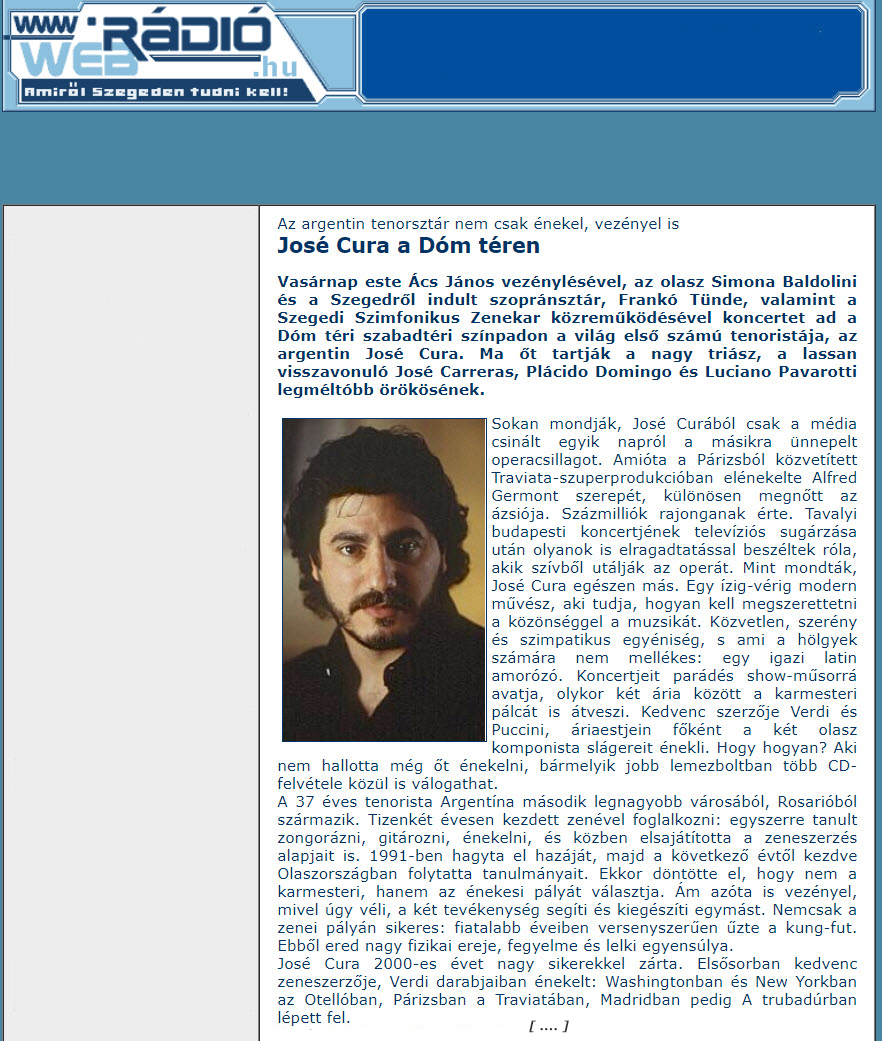

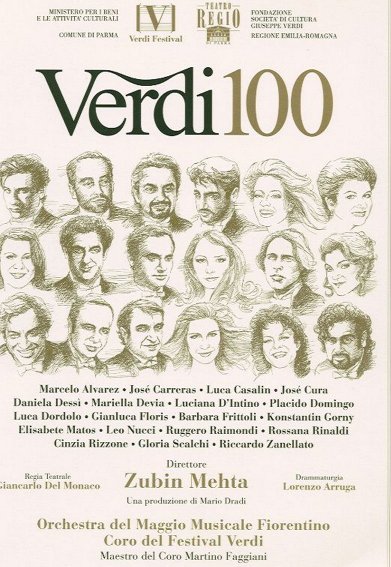

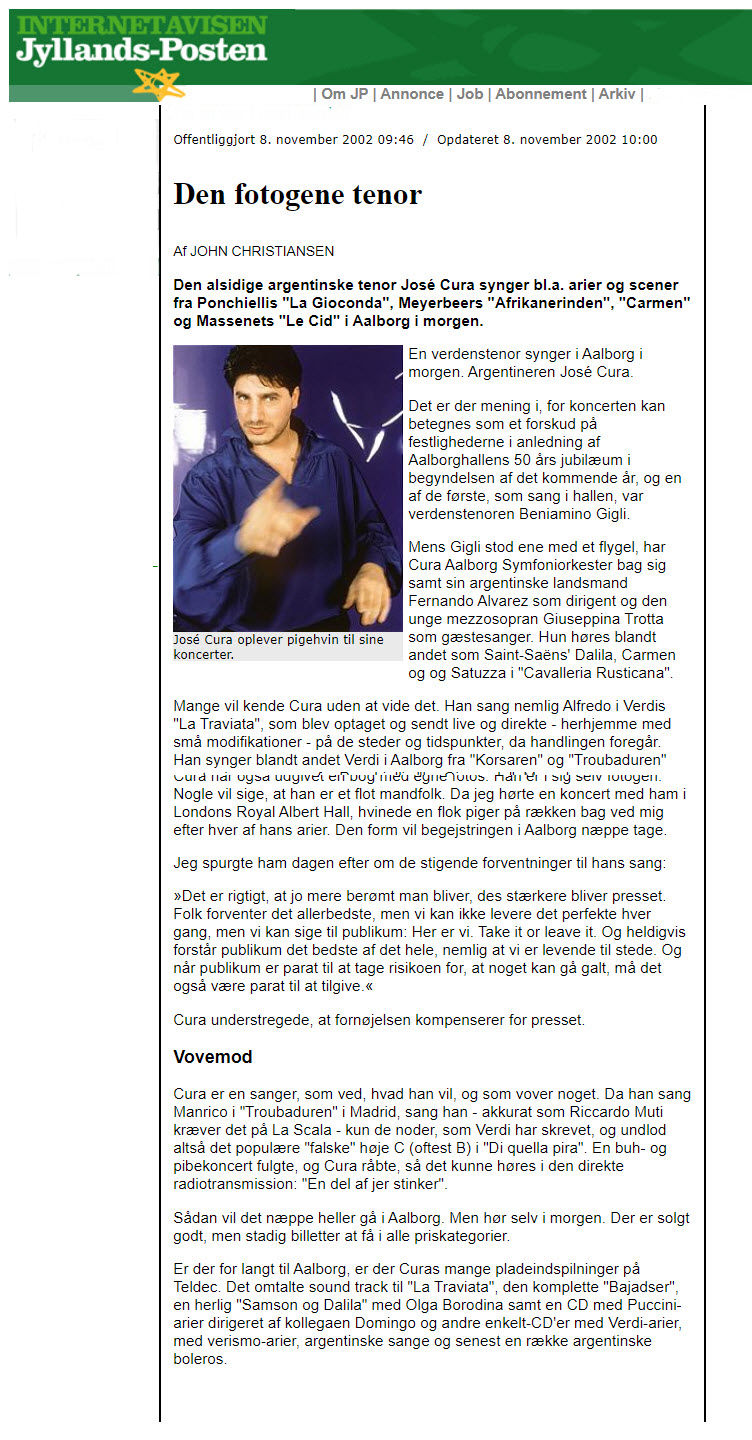

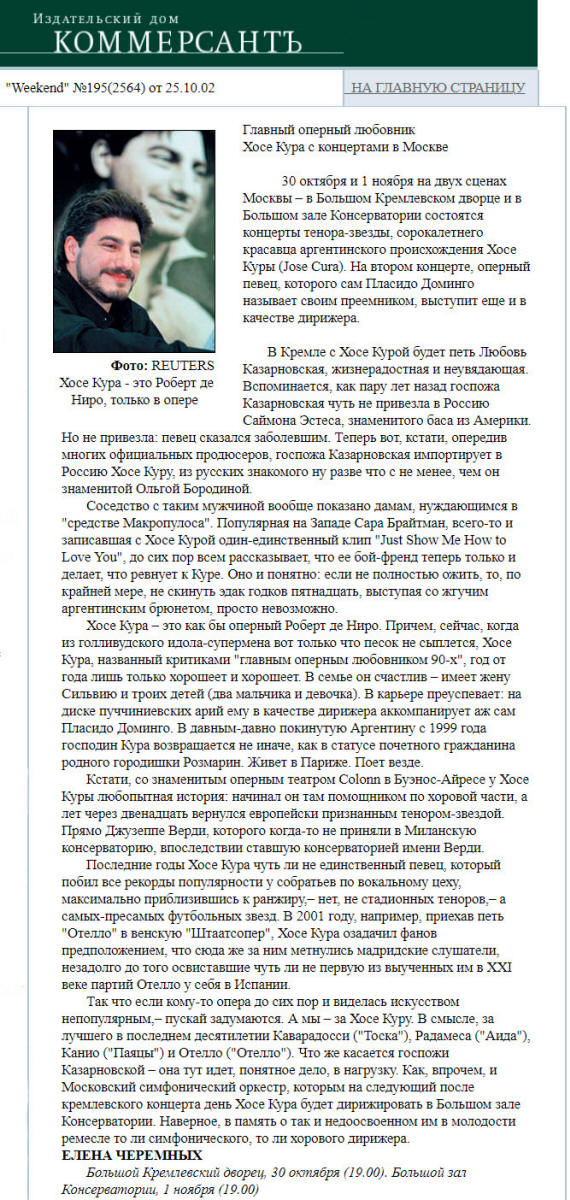

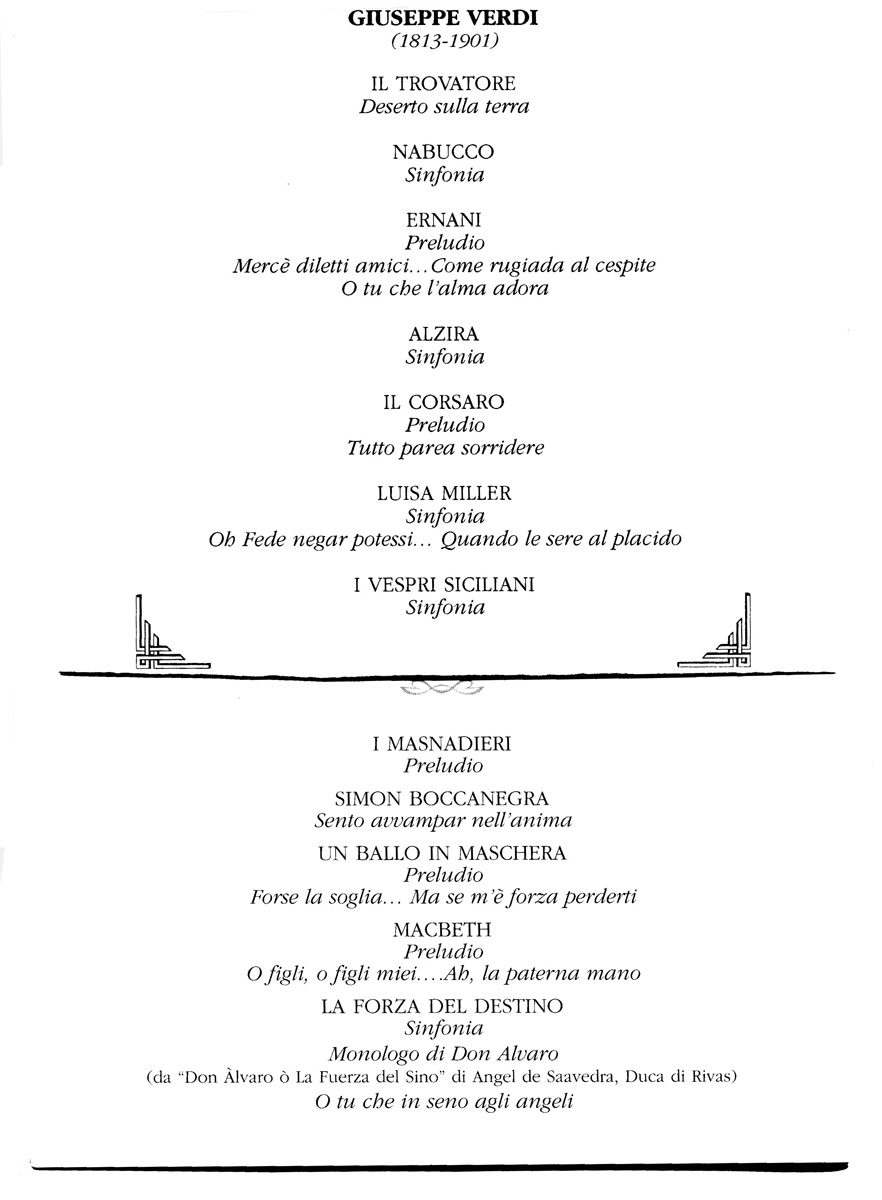

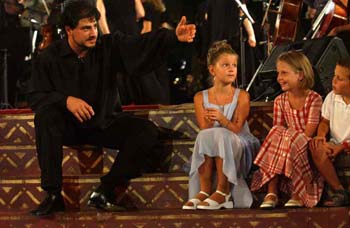

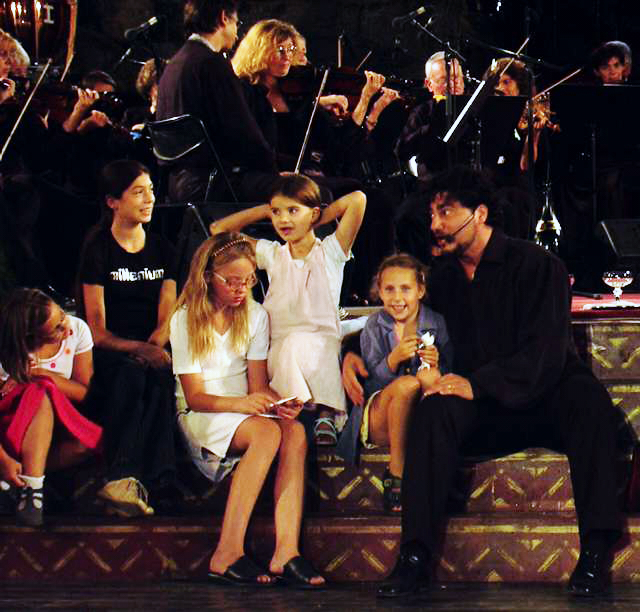

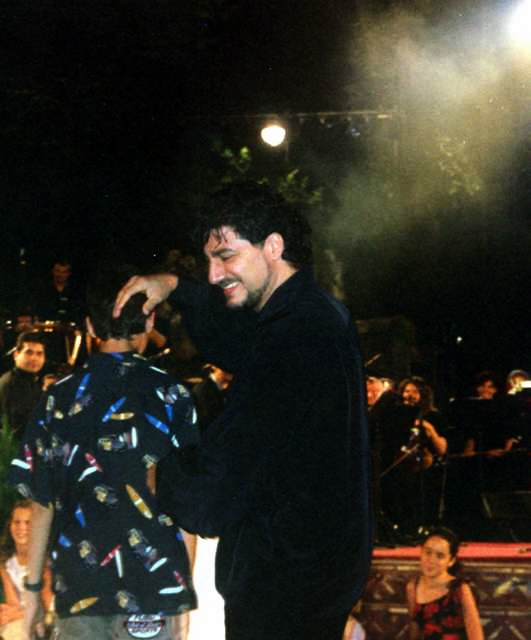

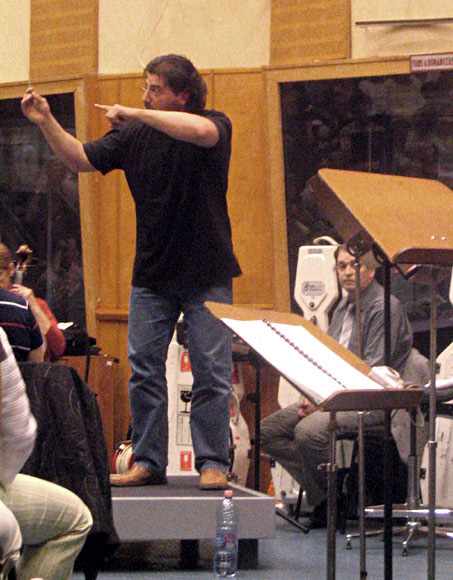

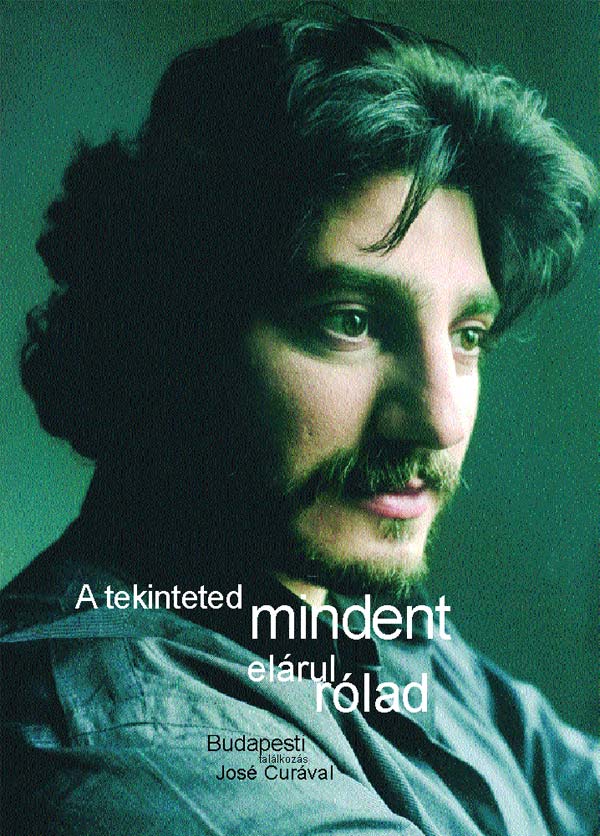

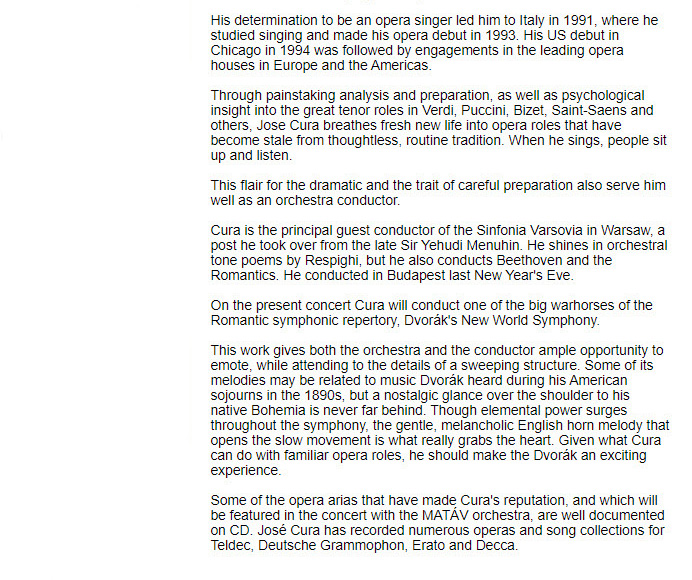

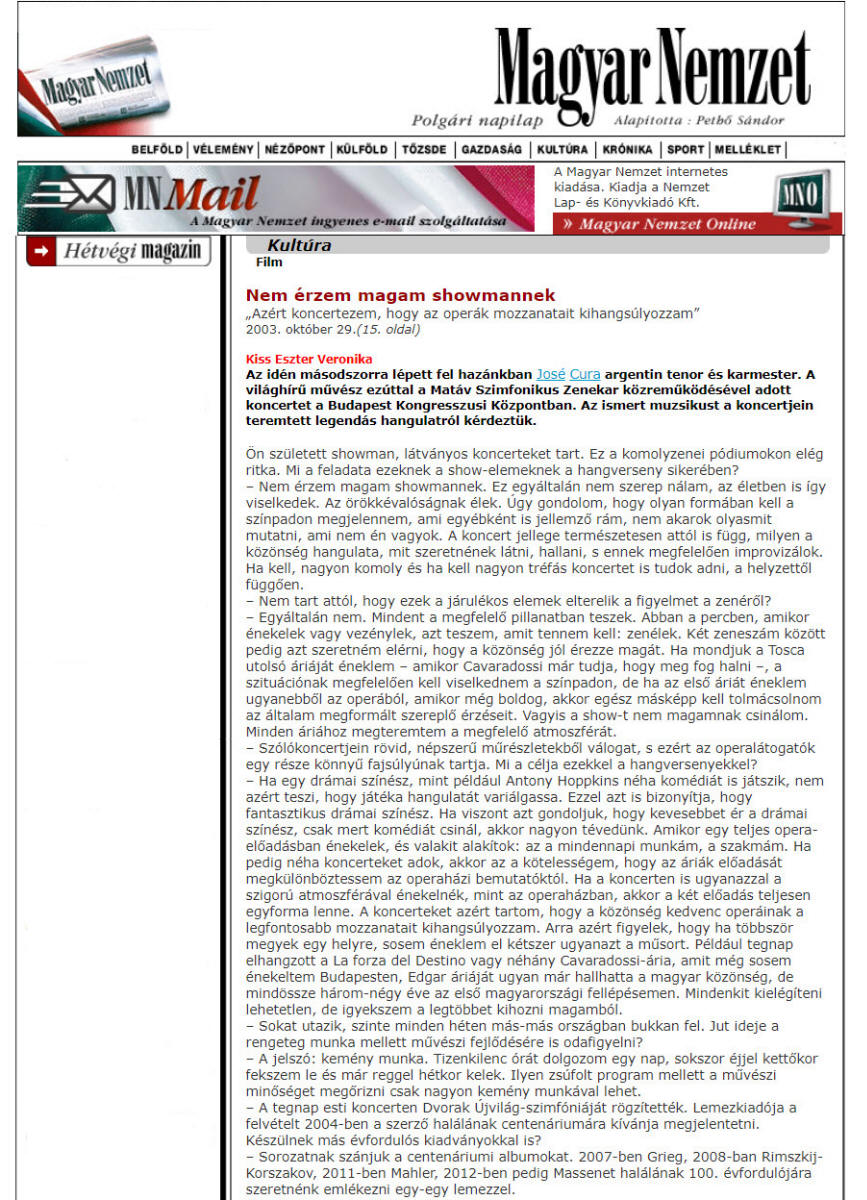

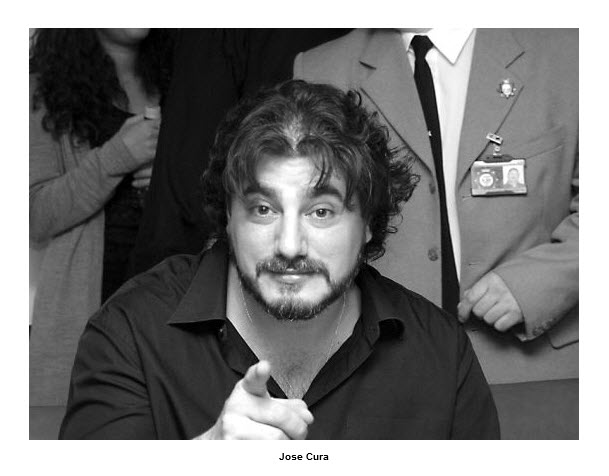

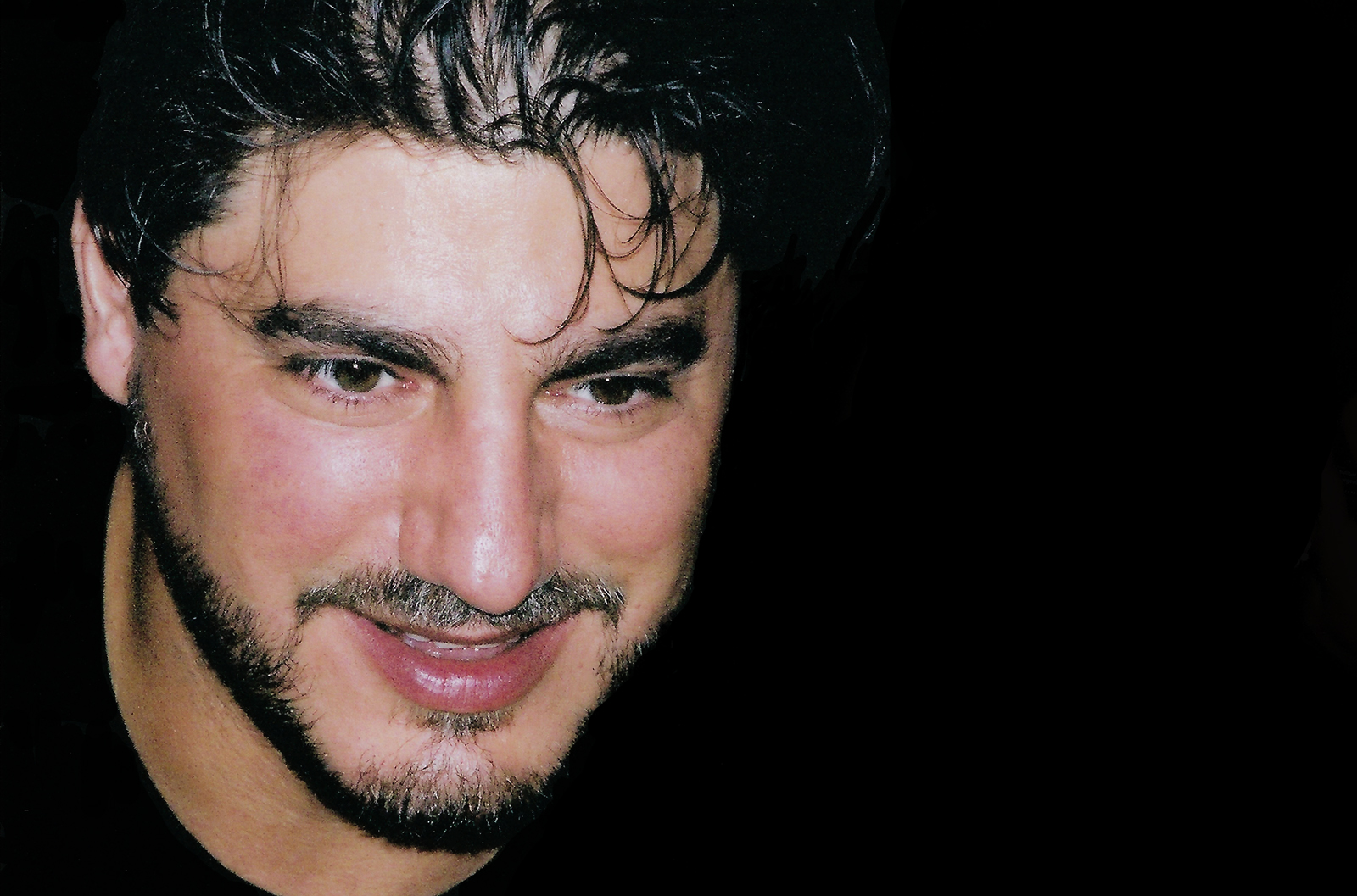

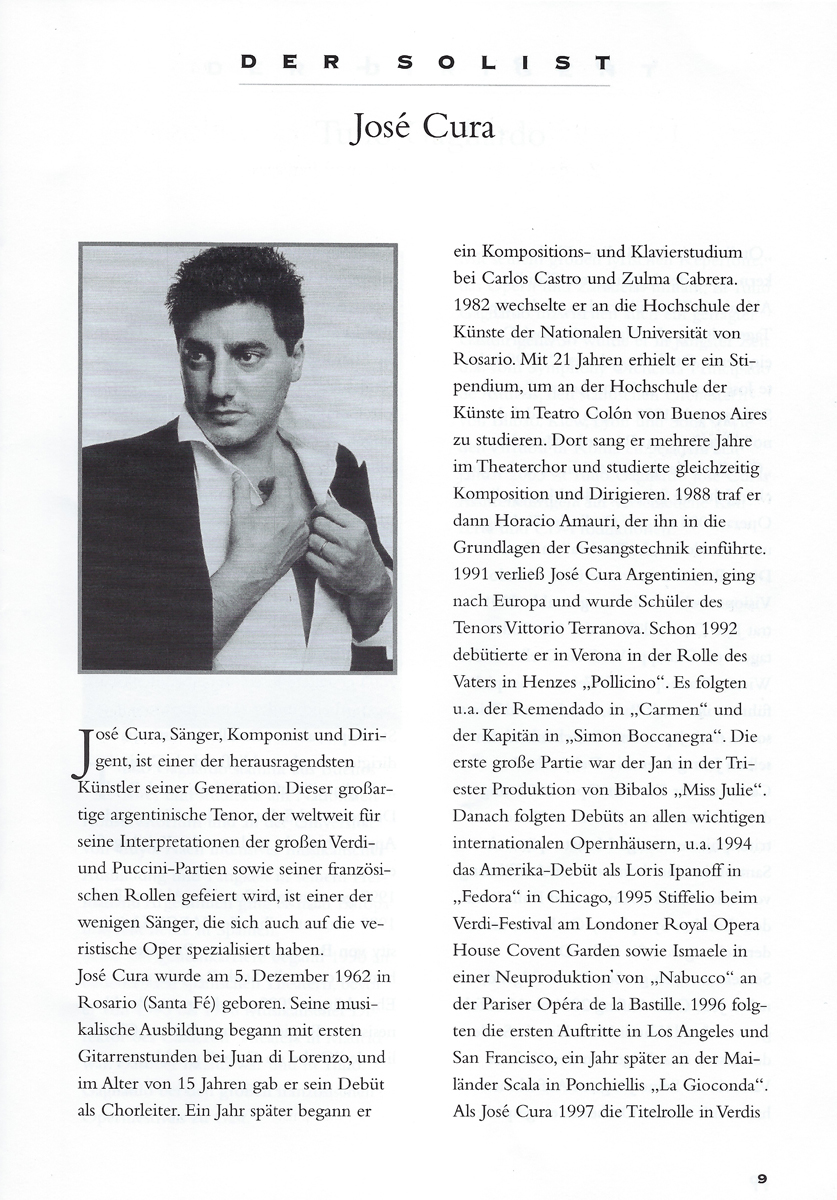

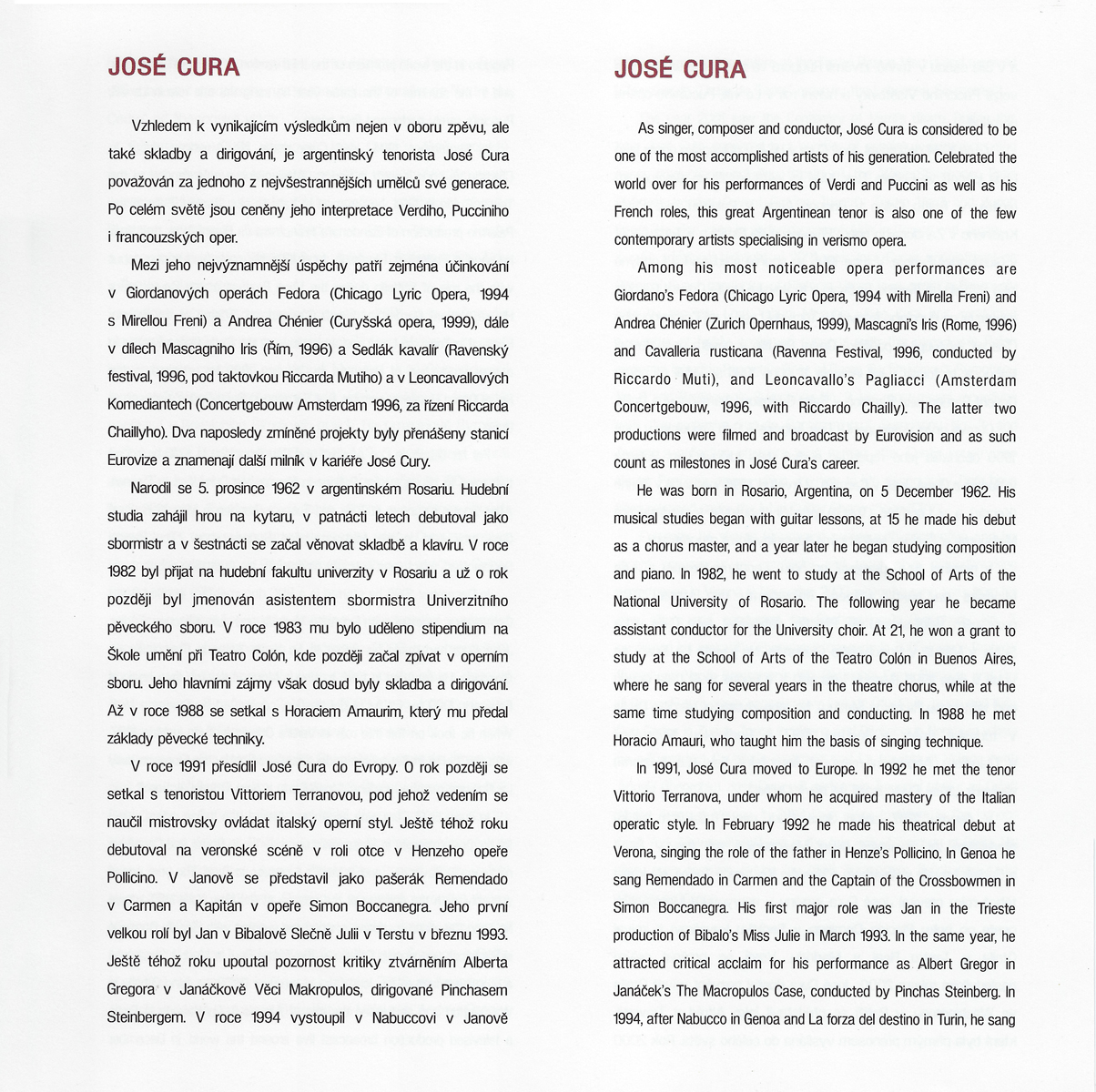

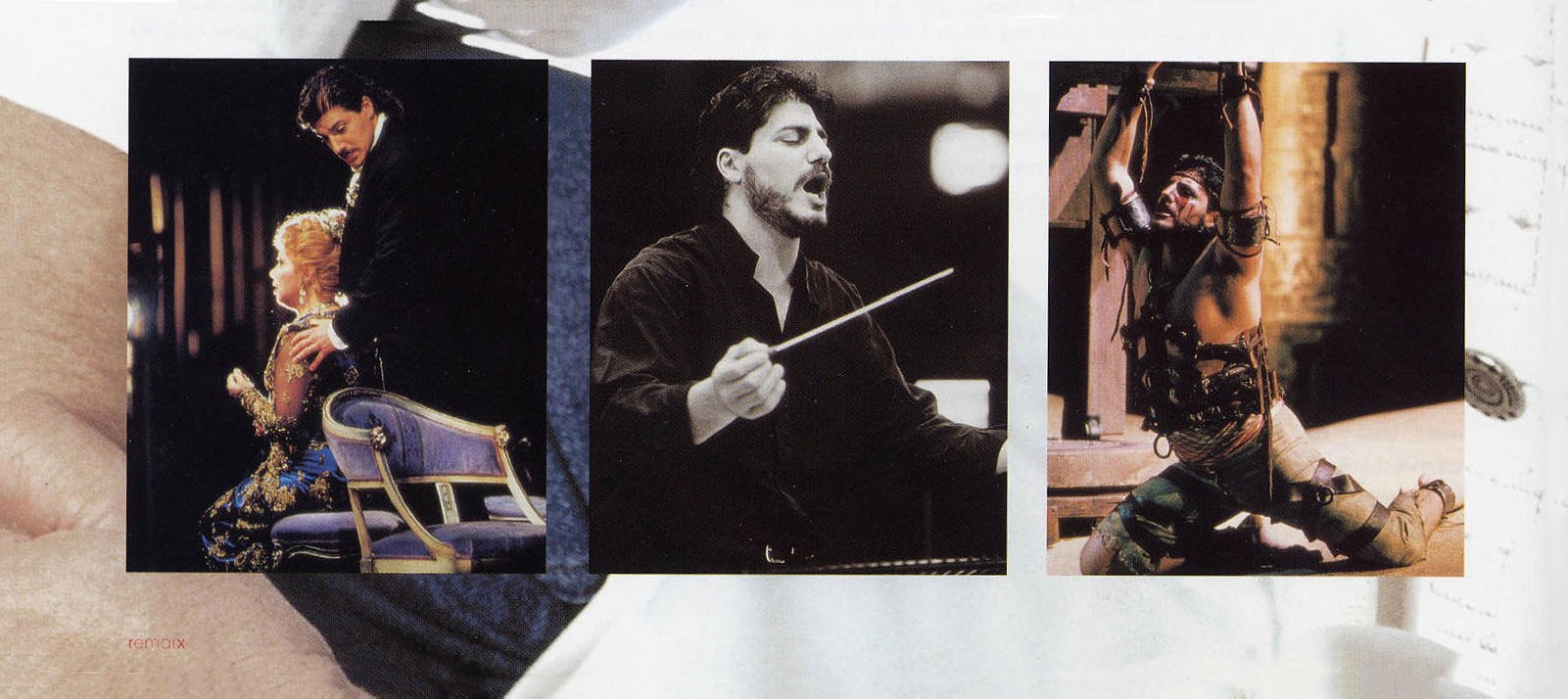

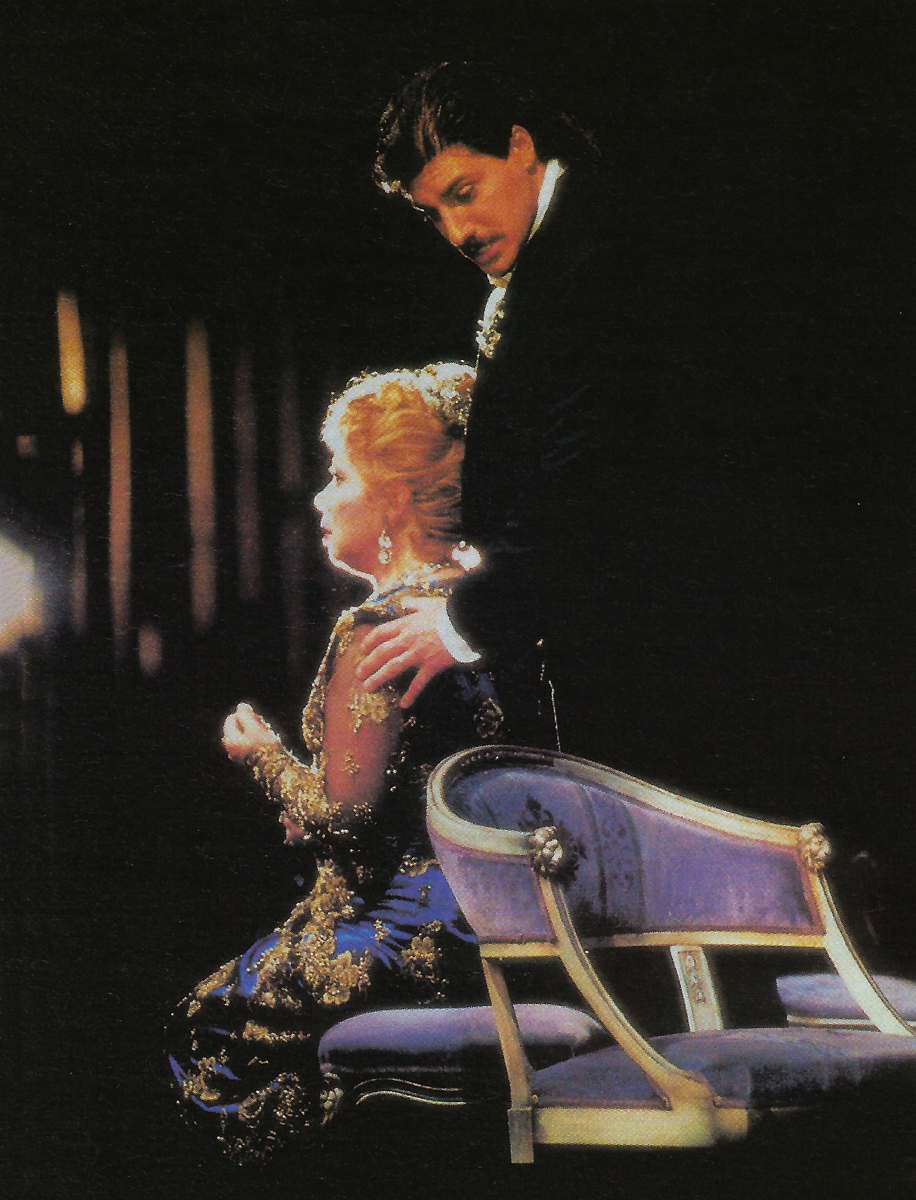

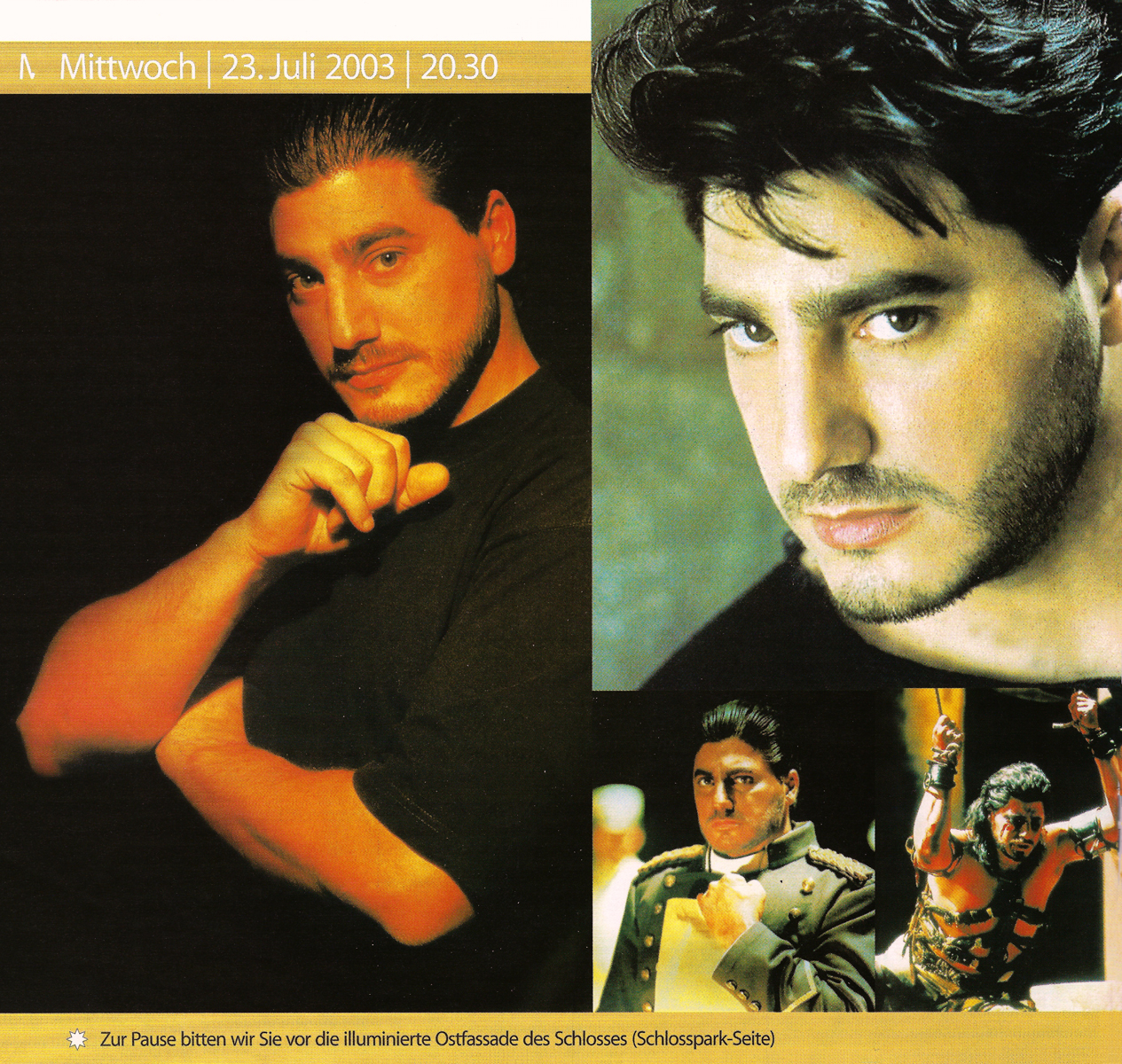

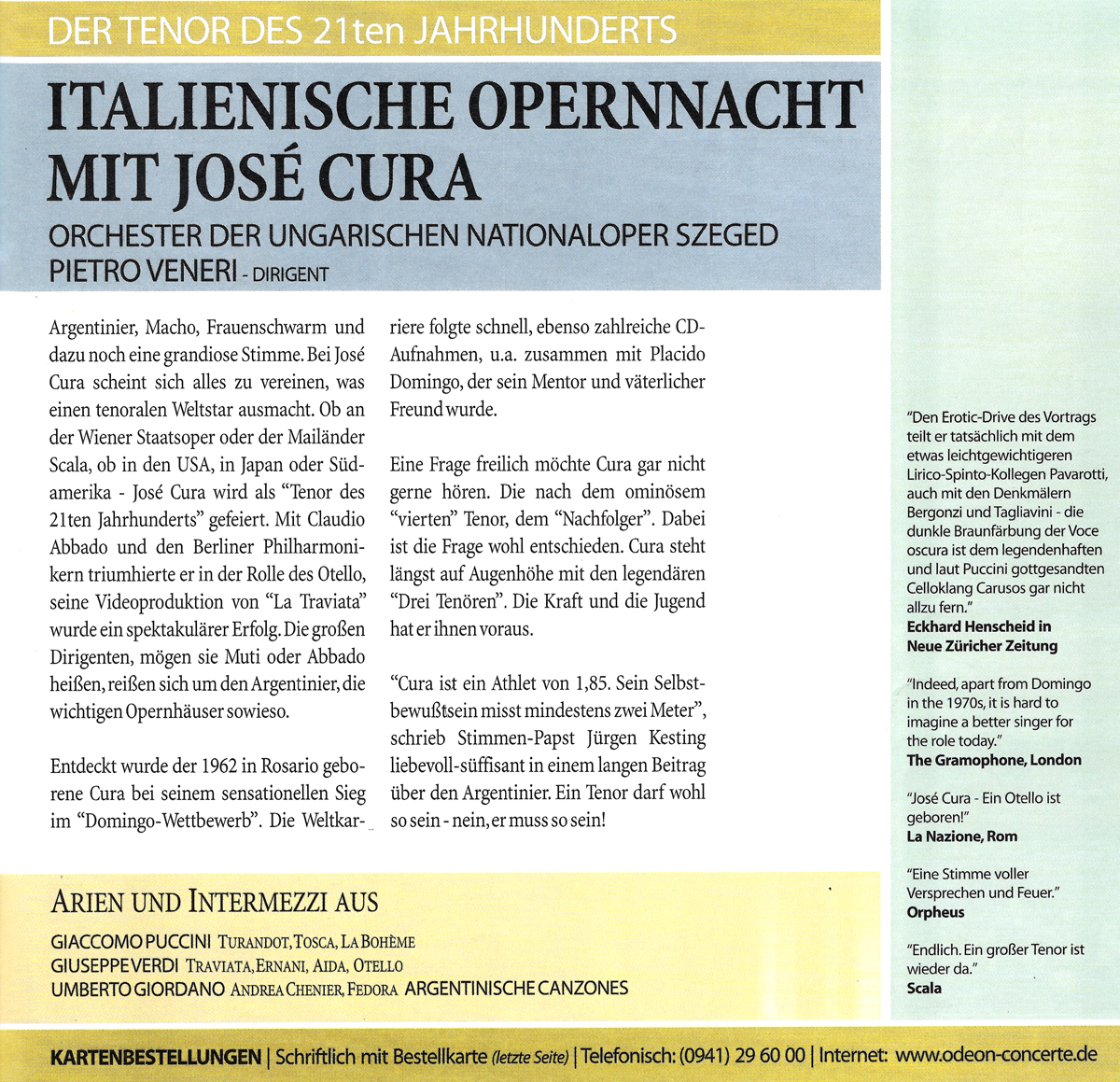

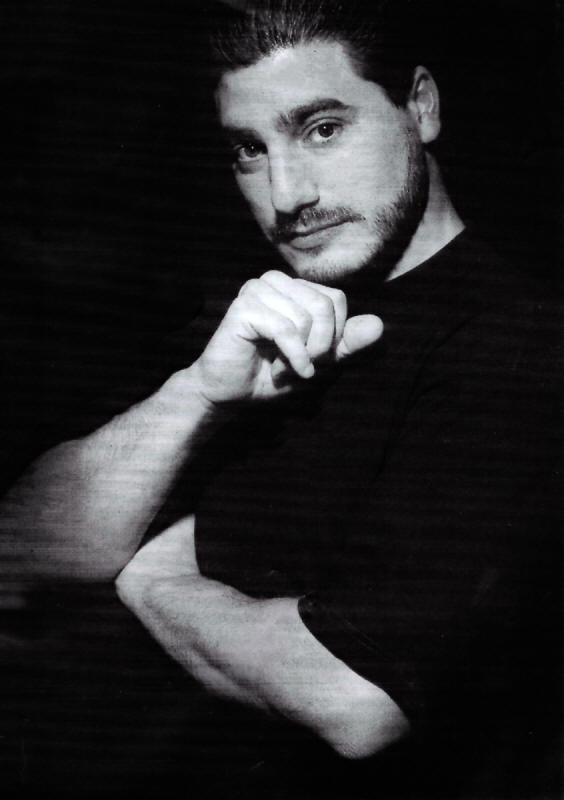

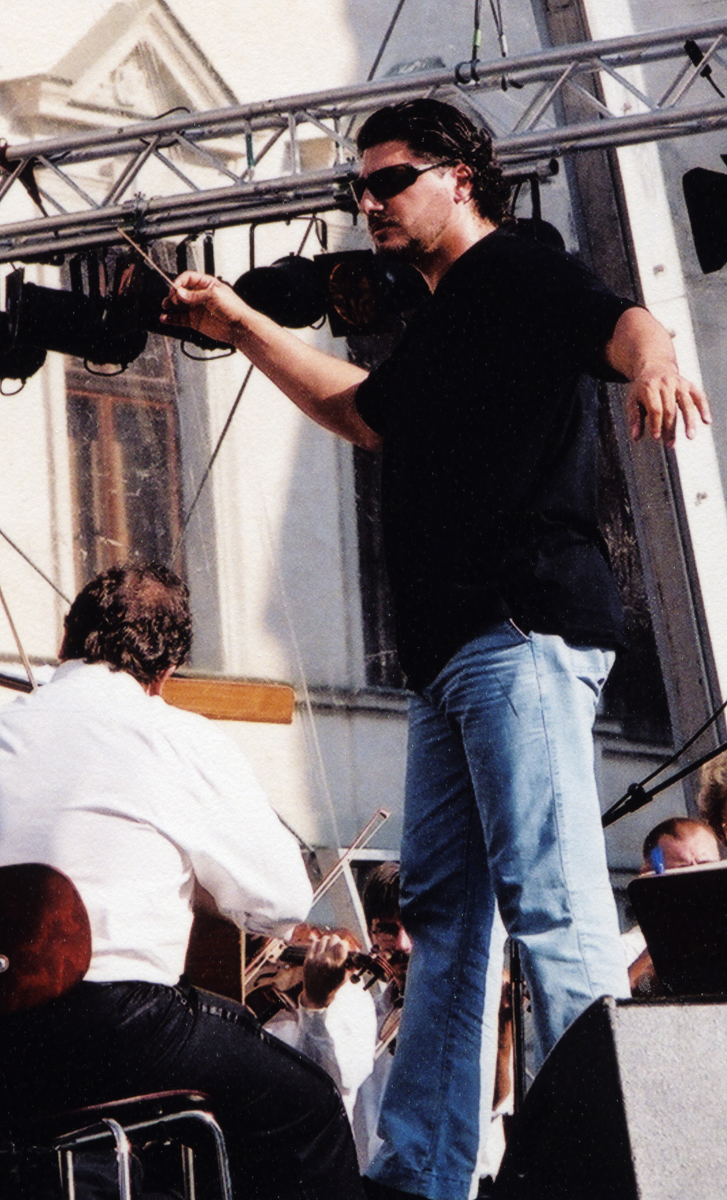

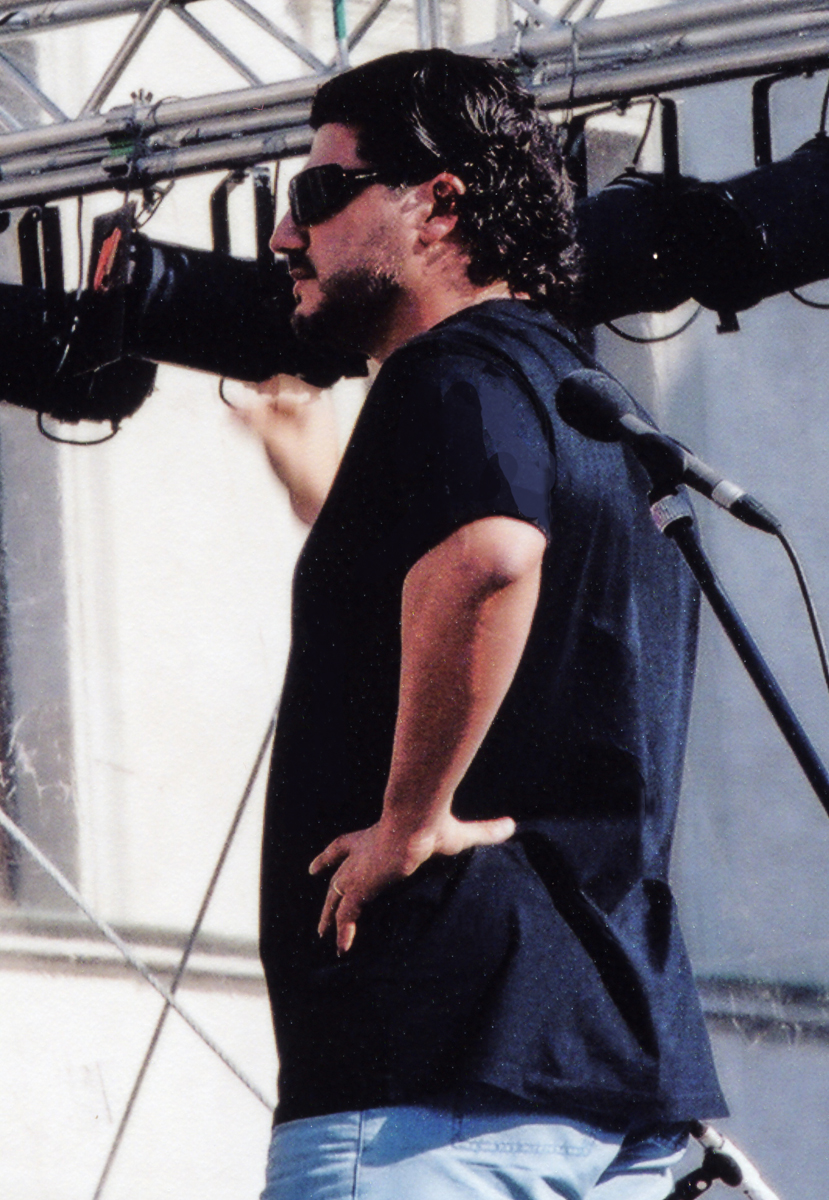

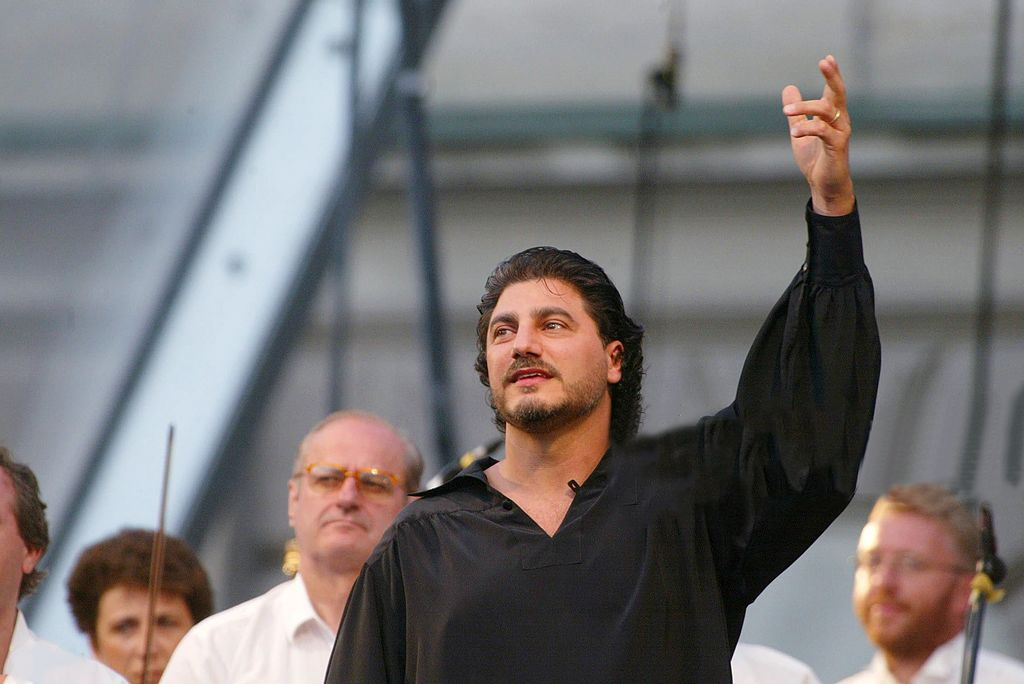

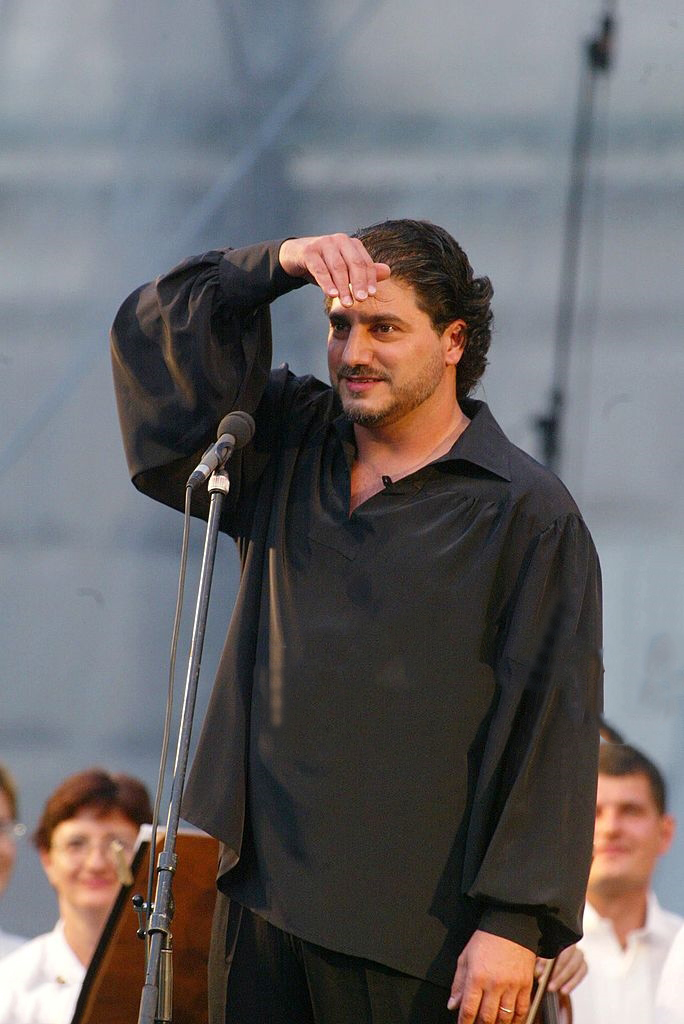

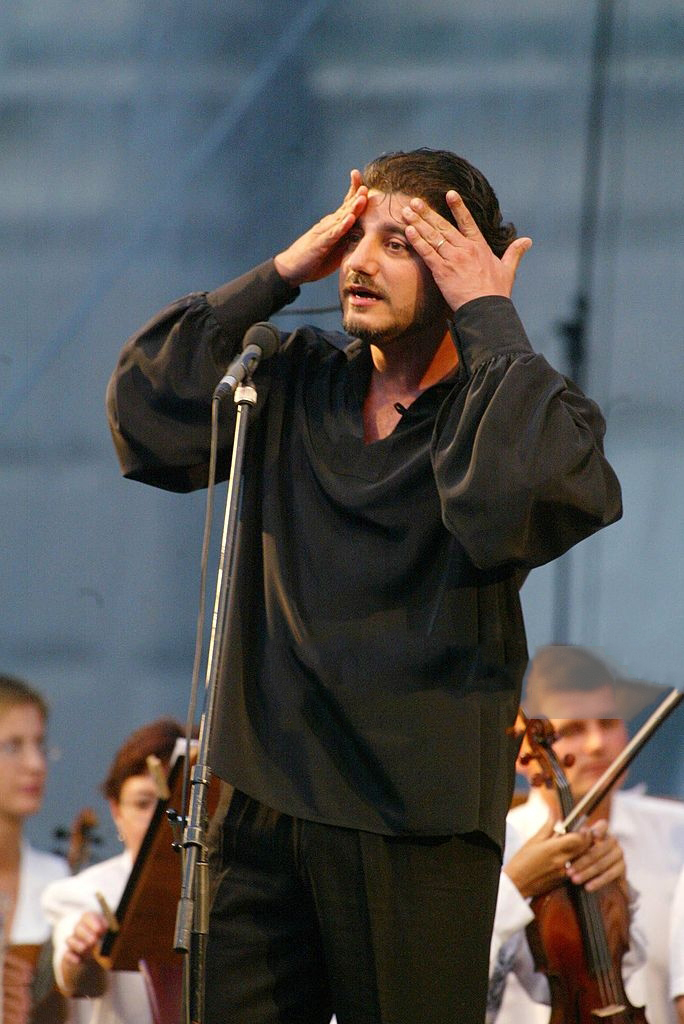

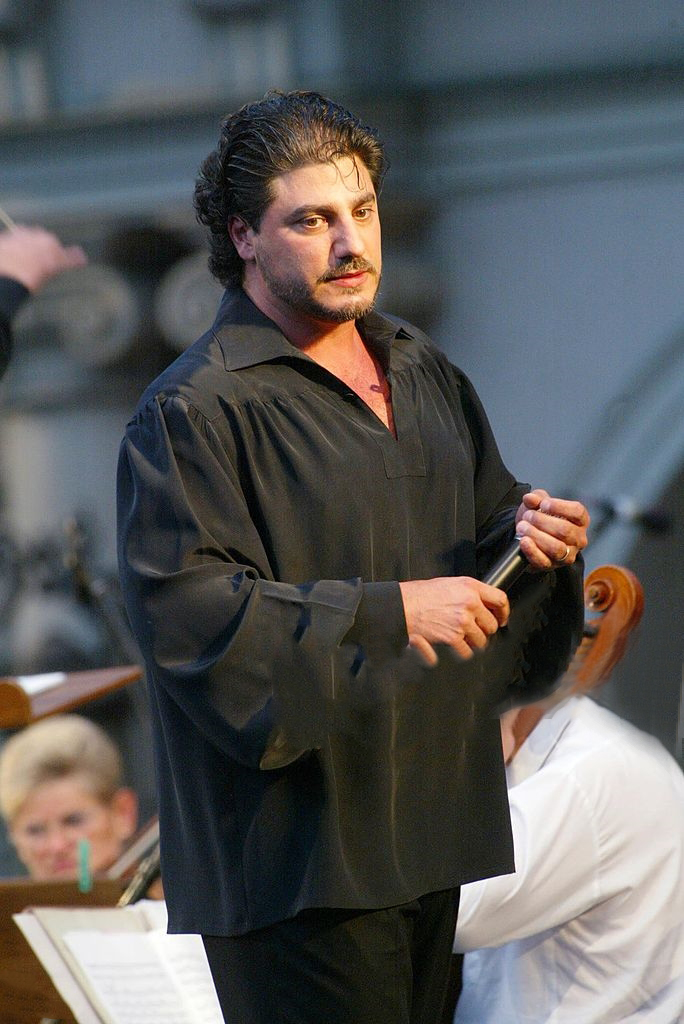

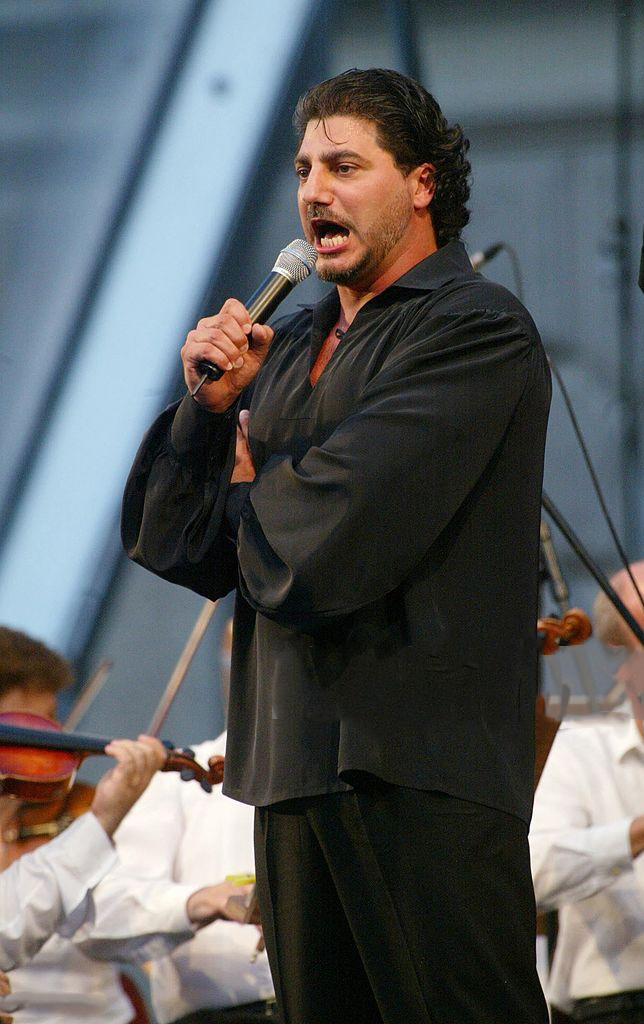

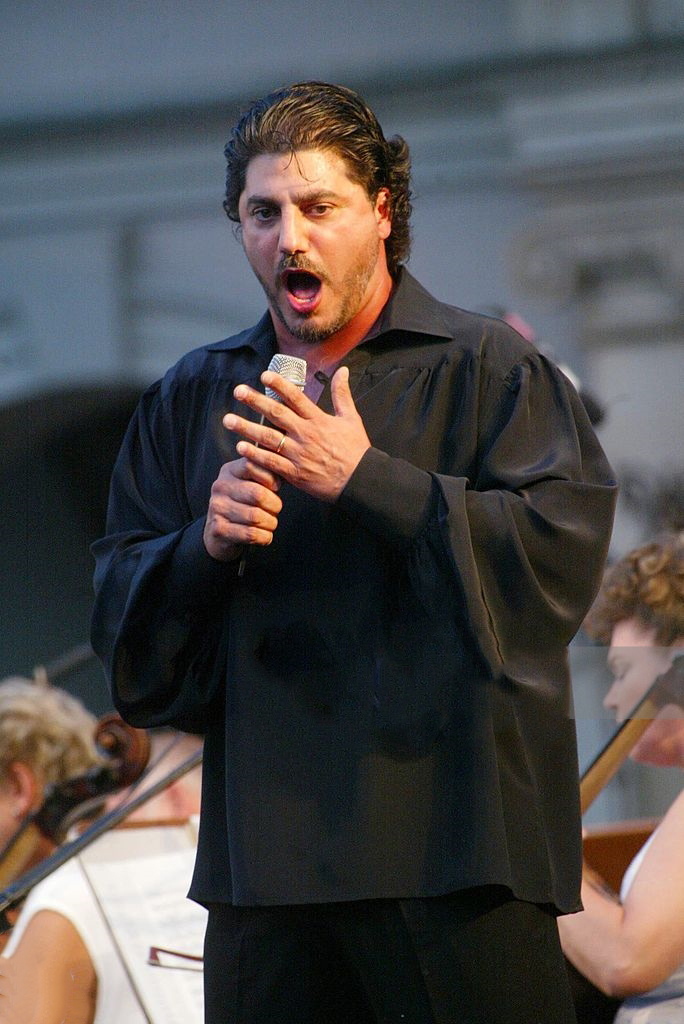

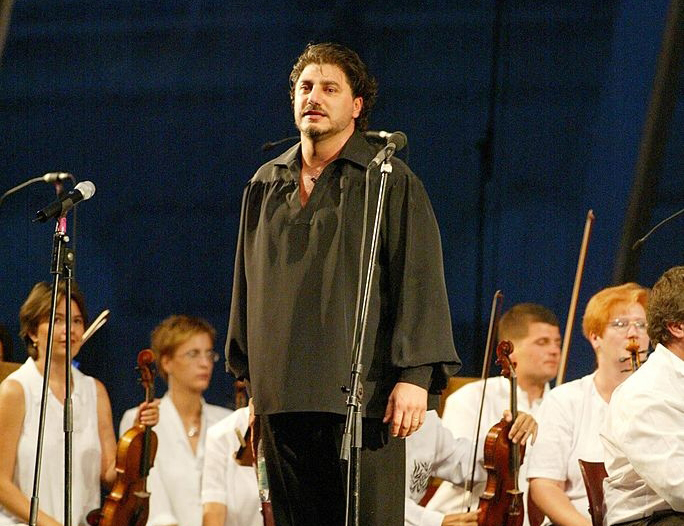

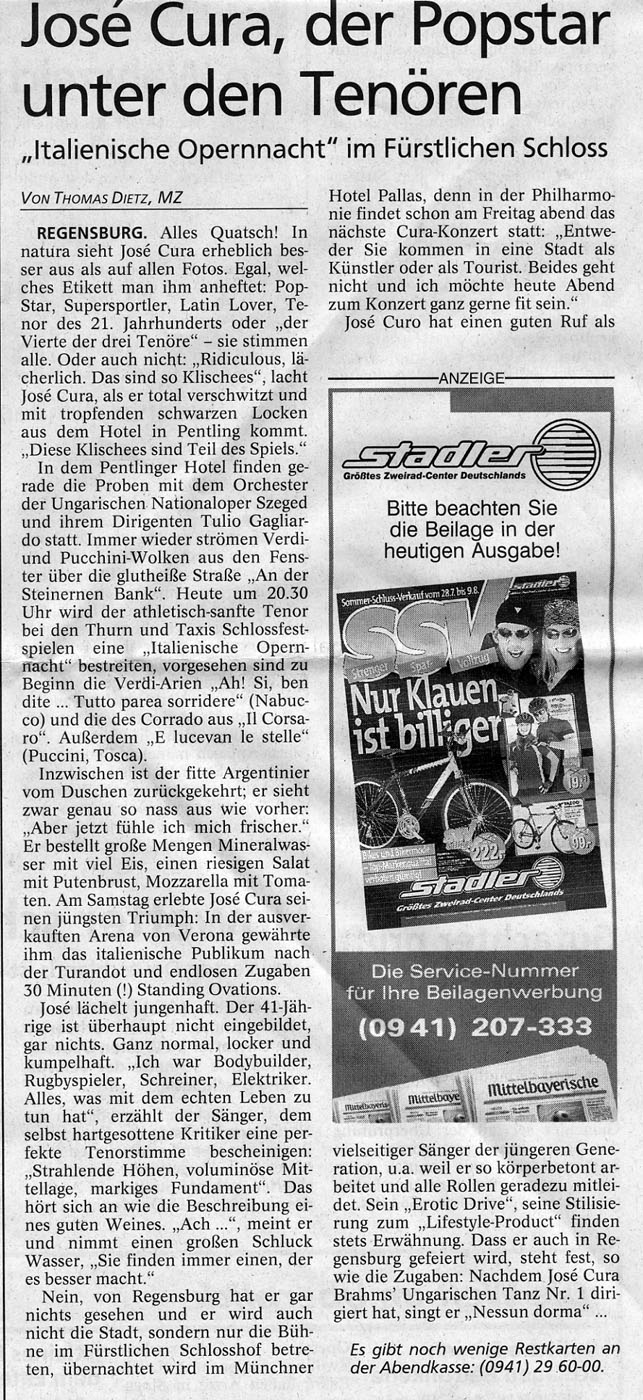

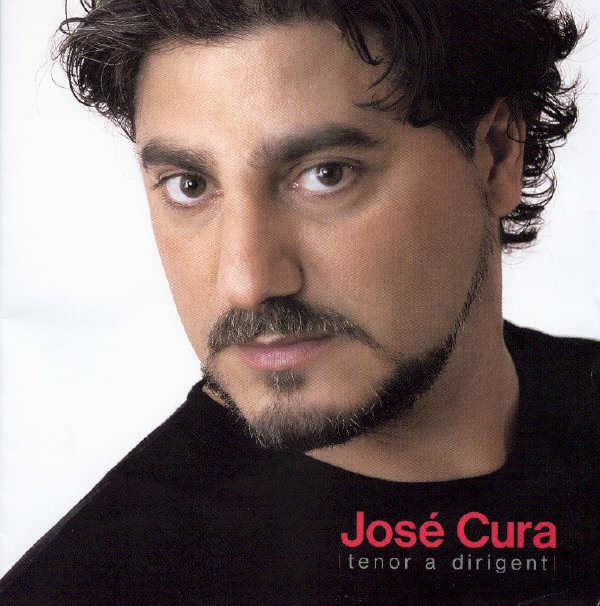

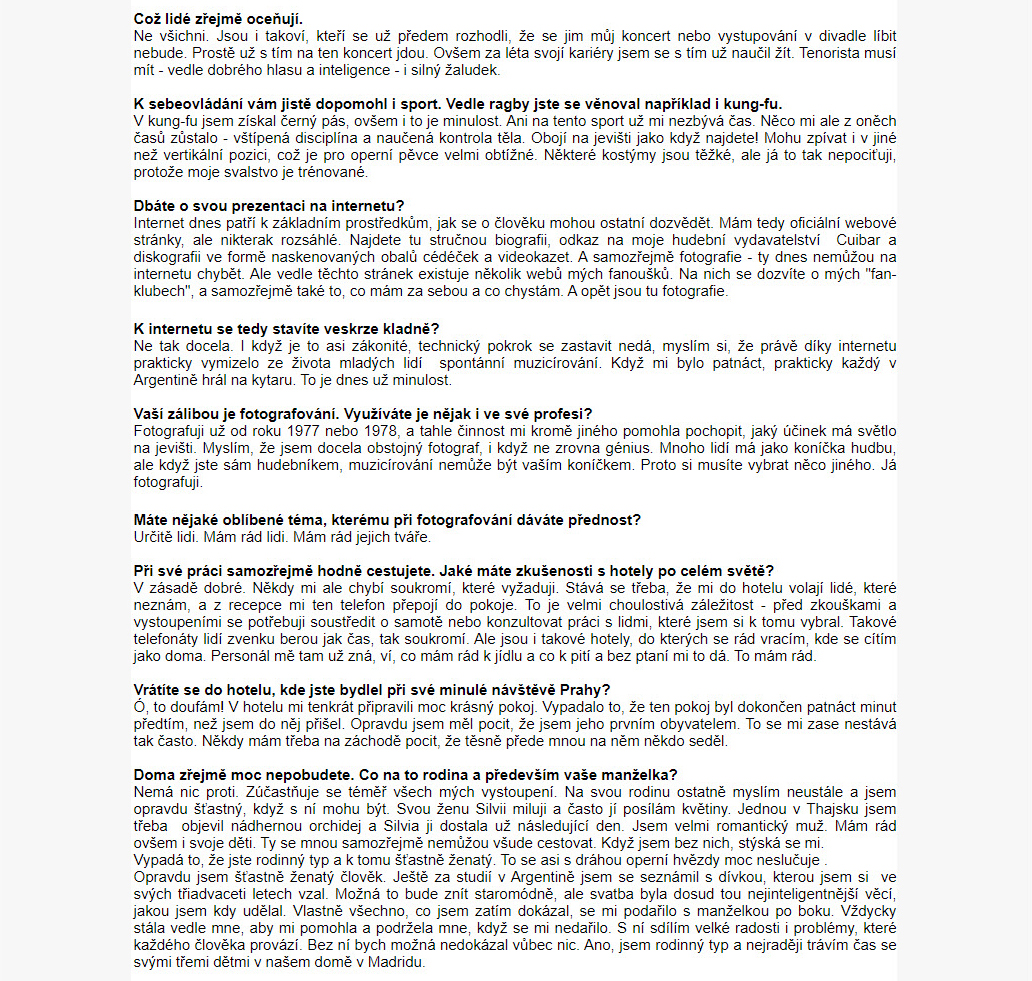

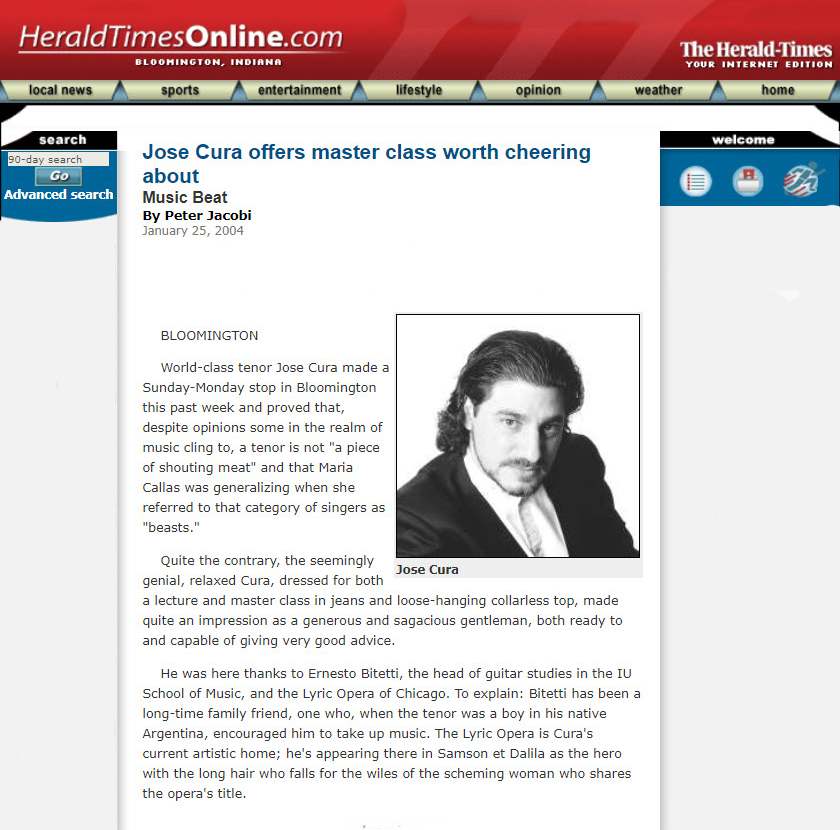

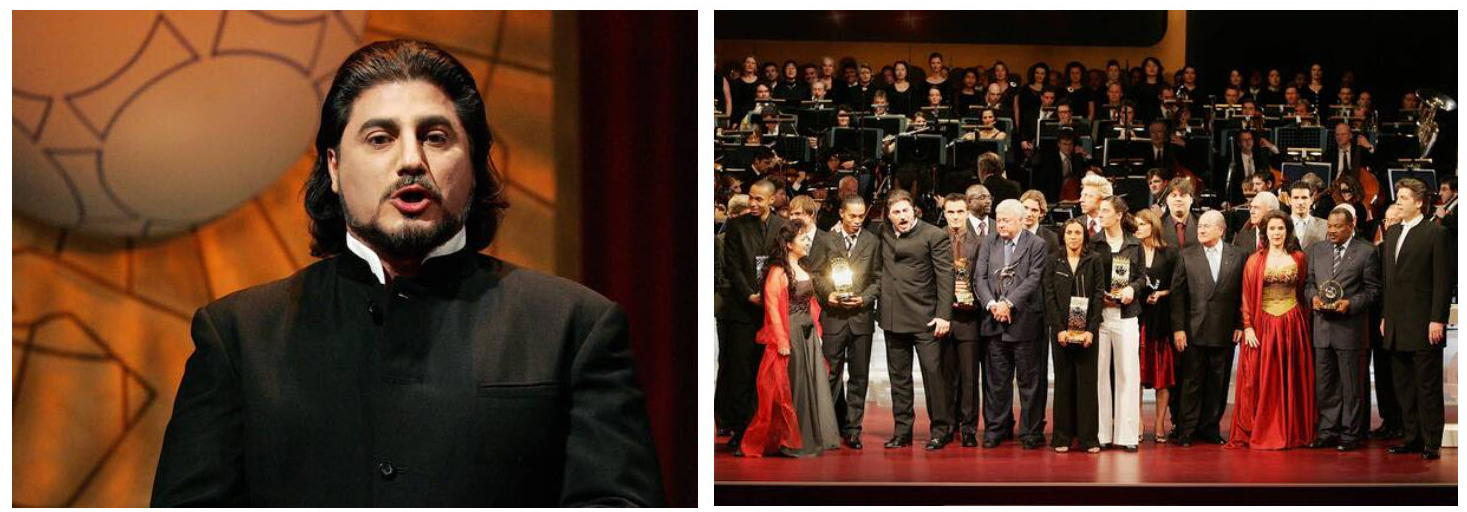

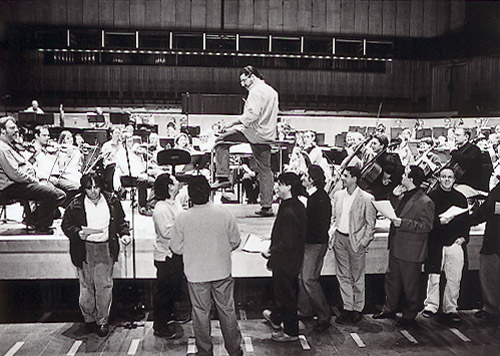

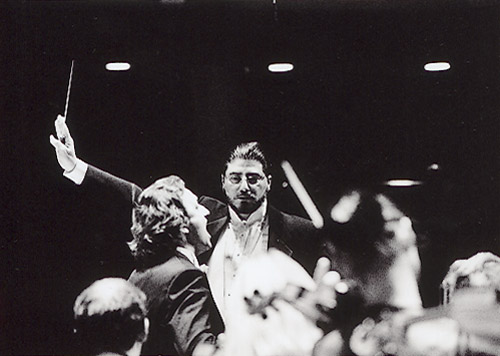

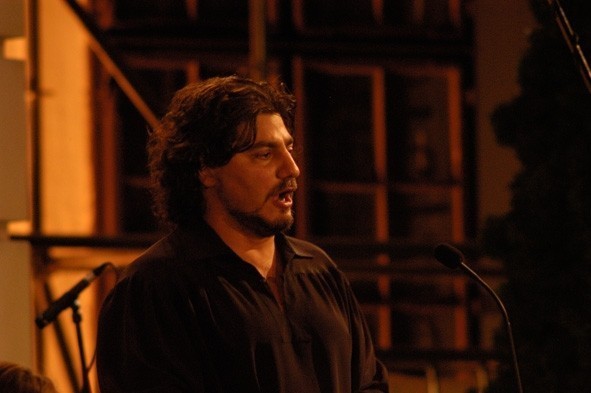

Benefits of Bodybuilding José Cura at the Erkel Theater Muzsika Csengery Kristóf September 2000 [Excerpt] The 38-year-old Argentinean singer, formerly a successful bodybuilder and [the winner] of the 1994 Domingo Singing Competition, has so far been known by the Hungarian music lover for recordings—and, of course, from the La traviata live from Paris performance, broadcast on 3 June by 102 television companies. The night of arias in Budapest was promoted by two advertising slogans. The posters read The tenor of the 21st Century. And the Hungarian television news, reporting on the artist's press conference, called him the fourth tenor - referring to the triumvirate of Carreras, Domingo and Pavarotti. After such history, the mortals on earth prepared for the great encounter with a great excitement. The circumstances at the Erkel Theater were already extraordinary: there was no program, and in the vast lobby a single homemade board announced to the audience of more than two thousand what the star was singing that night. Before the start of the 8: 00 concert, at 8: 15, all of a sudden, the busy ushers started handing out program booklets: it seems the printers had finally finished their work. The contents of the booklet were sometimes the same as the lobby board, sometimes not. A third version was offered after another quarter of an hour of waiting: it did not fully cover the contents of the board or the first booklet, but was similar to both. We participated in the game: when we reached an identifiable number, everyone nodded contentedly; and when rarities were heard, the excitement of guessing spiced up the experience. Who would ever think to complain: José Cura was among us, he sang to us, what difference did any of it make? Indeed, it seemed to make almost none. Moving from aria to aria, listening to Verdi, Puccini, Cilea, Leoncavallo, we begin to understand: it was not the composer or the style, it was not the character or the dramatic situation that mattered—everything here was defined by the personality of the singer. And what was this personality like? First and foremost, rich and original. As in the first vocal performance of the show, Puccini's Edgar Act II aria, when he arrived on stage and disarmed us with his form-breaking ingenuity. Under the baton of János Ács, the Failoni Orchestra of the Hungarian State Opera was in the thick of its instrumental introduction, but for the time being the singer was nowhere to be seen. Suddenly he appeared at the back, in the depths of the stage, in black trousers, black silk shirt, with his hands in his pockets, and he sauntered into the limelight. What an idea! Some of us whispered, already enchanted. This artist certainly knew how to surprise the audience! It is also understandable and justifiable that Cura repeated this impressive trick every possible time throughout the concert: let the audience listen to him and remember him well. Throughout the concert, we saw the benefits of a former bodybuilding lifestyle: during his songs, José Cura, bursting with energy, tirelessly walked across the stage, sometimes walking back and forth between the musical stands. He sang an extremely personal melody while leaning on one of the lady musicians; on another occasions he targeted those in the front row of the auditorium with his deep, fiery gaze. He didn't stop for a moment: he was moving, walking, and going, incessantly. The singer performed Vesti la giubba from Pagliacci on his knees - a great idea, especially because, in the appropriate passage when Canio is singing about applause, José Cura could aptly illustrate: he clapped ... At other times he came to the stage with a pink terry cloth towel to bow—a kind, direct gesture that indicates the artist is also human. Similarly, I found it attractive that at the height of the celebration, the handsome tenor bent down to the front row and raised up a little boy. It is important for the audience to know that this singer is warm-hearted and loves children. In truth, not everyone on the ground shared my opinion. I was sitting next to a skinny man in his forties and this obsessive nuisance added a bitter note to everything. I heard him whisper to his lady partner: Cura is singing beyond his means. Nice thing, I thought to myself, to insult a great artist like that! He didn't even consider [Cura’s] voice special: he said it was a solid, powerful, penetrating voice, but often raw in the middle position and without lightness in the dynamic range below forte. Such are the fanatic opera-lovers: you can bring the star down from the sky but it's not enough for them. Speaking of heaven: my neighbor missed the heights as well: according to him, Cura had “shown” almost none during the concert, except for the single peak in the closing line of Nessun dorma (Puccini: Turandot) performed as an encore. Even the many aesthetic, heroic movements of conductor José Cura did not convinced this infidel: he said, of his capacity as a conductor (Manon Lescaut-intermezzo; Overture to La forza del destino) that the tenorist offered the same as the singer – empty pretense that was not about music but rather exclusively for personal success. This all-out sourpuss found Pinkerton’s farewell aria (Addio, fiorito asil) and Cavaradossi’s hit (E lucevan le stelle) to be a primitive self-portrayal by the singer… And he went even further as he murmured to himself: Why isn't this born showman making his living in the world of light music, when it was clear that God has created him as a rival for Andrea Bocelli, and that everything he was doing was part of the entertainment industry, just pure business. At this point I had had enough of my neighbor. At the next applause, I stood up and listened to the end of the concert in a quieter place, where no one bothered me with inappropriate comments. Because I love José Cura and I think I could adore him… I haven’t even mentioned what an educated musician he is. It had not escaped his attention that the concert date coincided with the 250th anniversary of Bach’s death. He said a few words to the audience about Johann Sebastian: he praised him, told us he was a great composer, and then sang Gounod’s Ave Maria in his memory—beautifully, faithfully, and emotionally as he should have. Next time he returns to Budapest, I’ll be clapping in the front row.

|

|

|

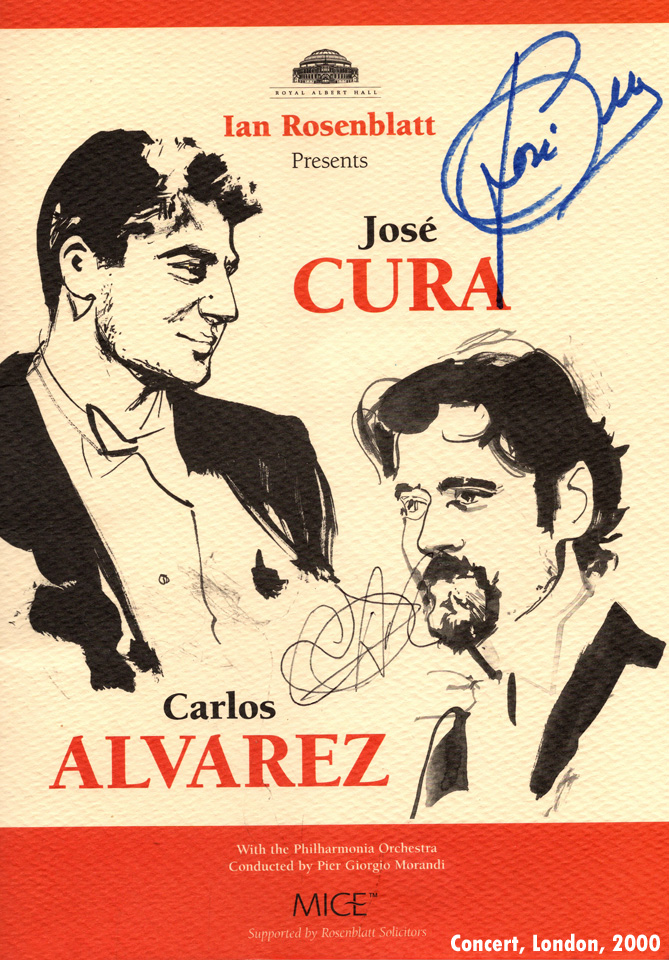

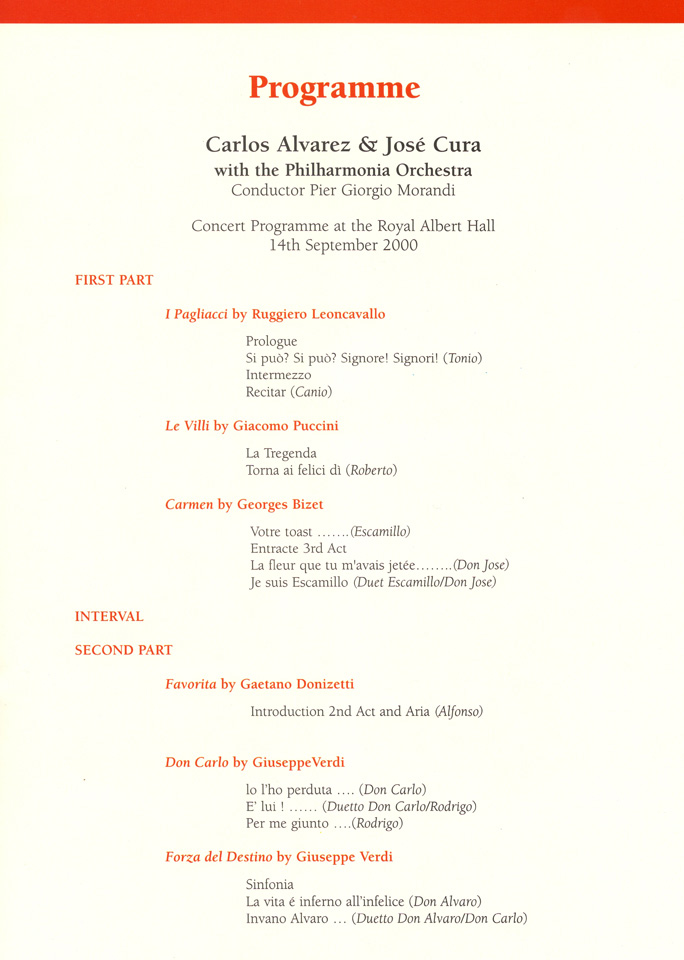

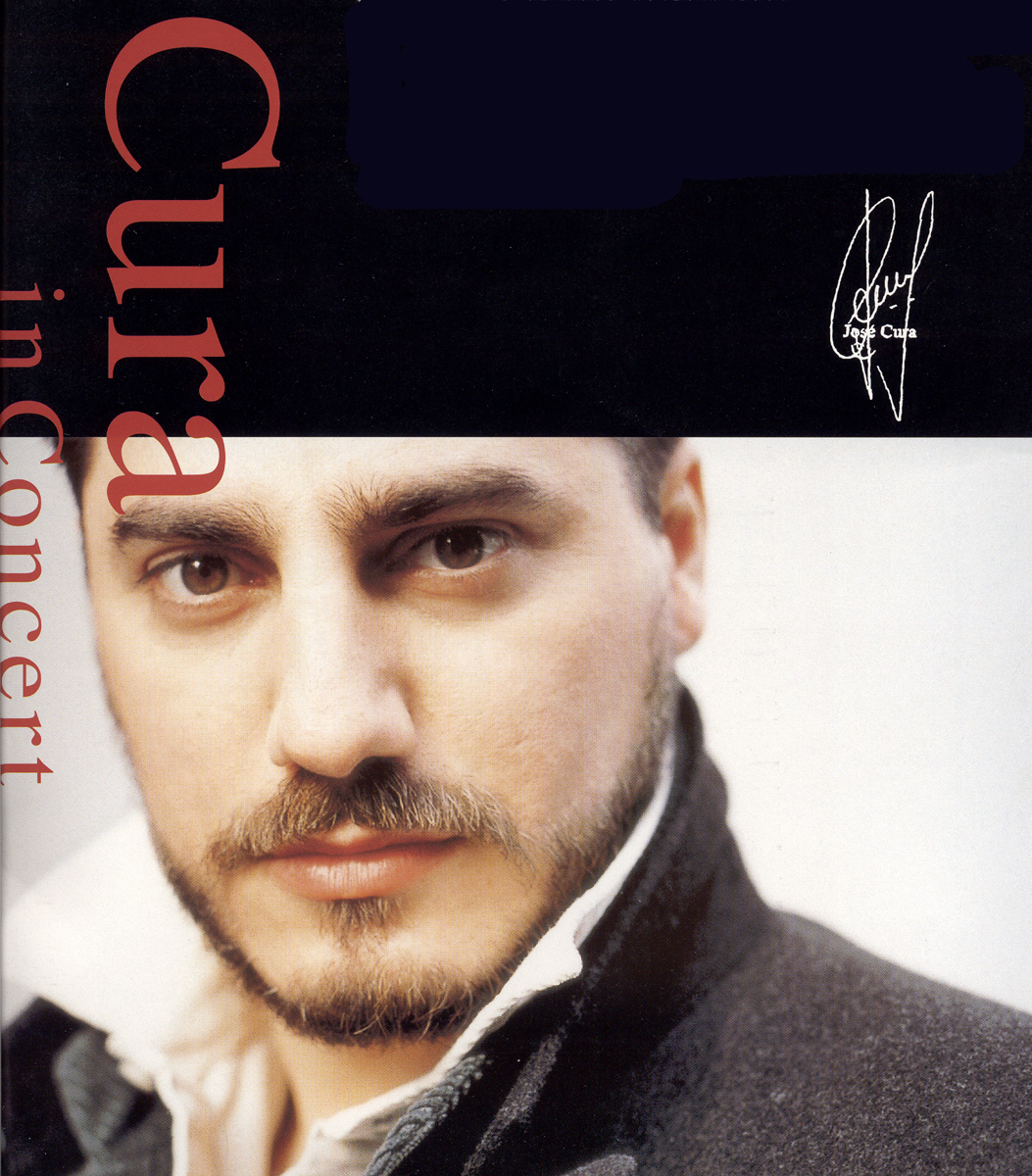

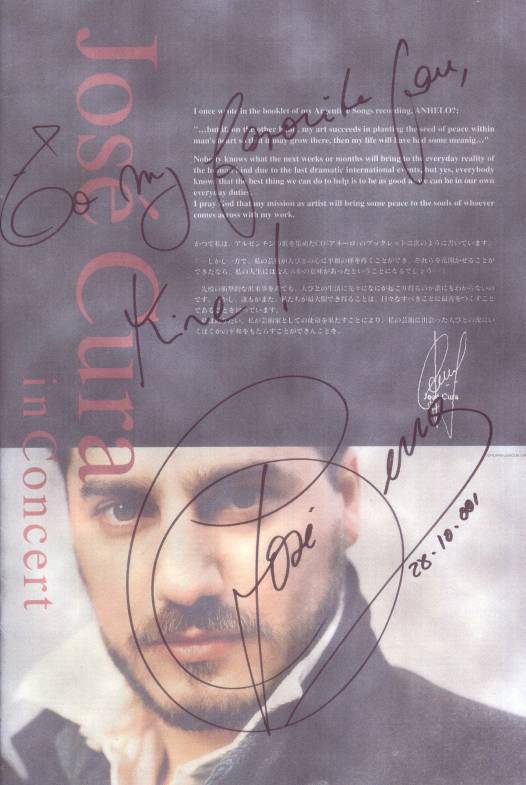

Royal Albert Hall

London

September 2000

|

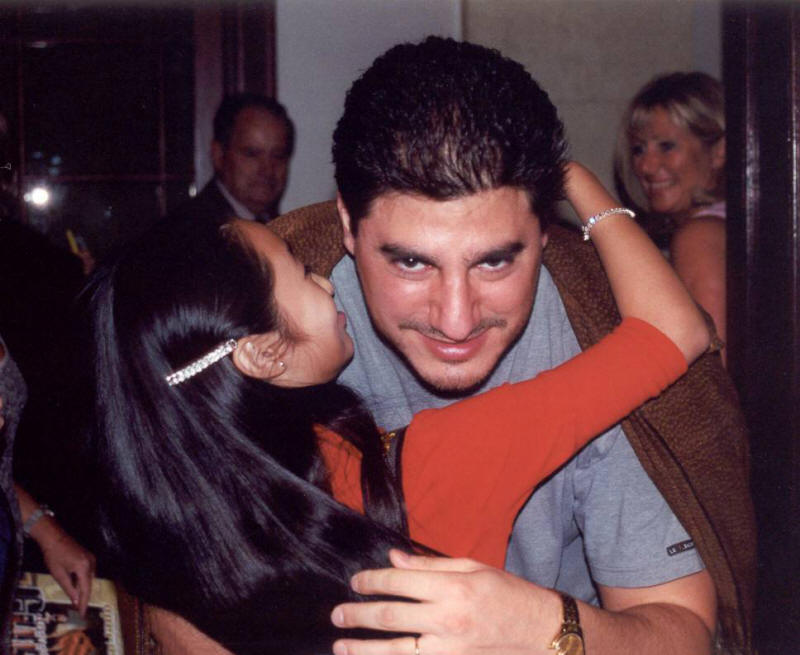

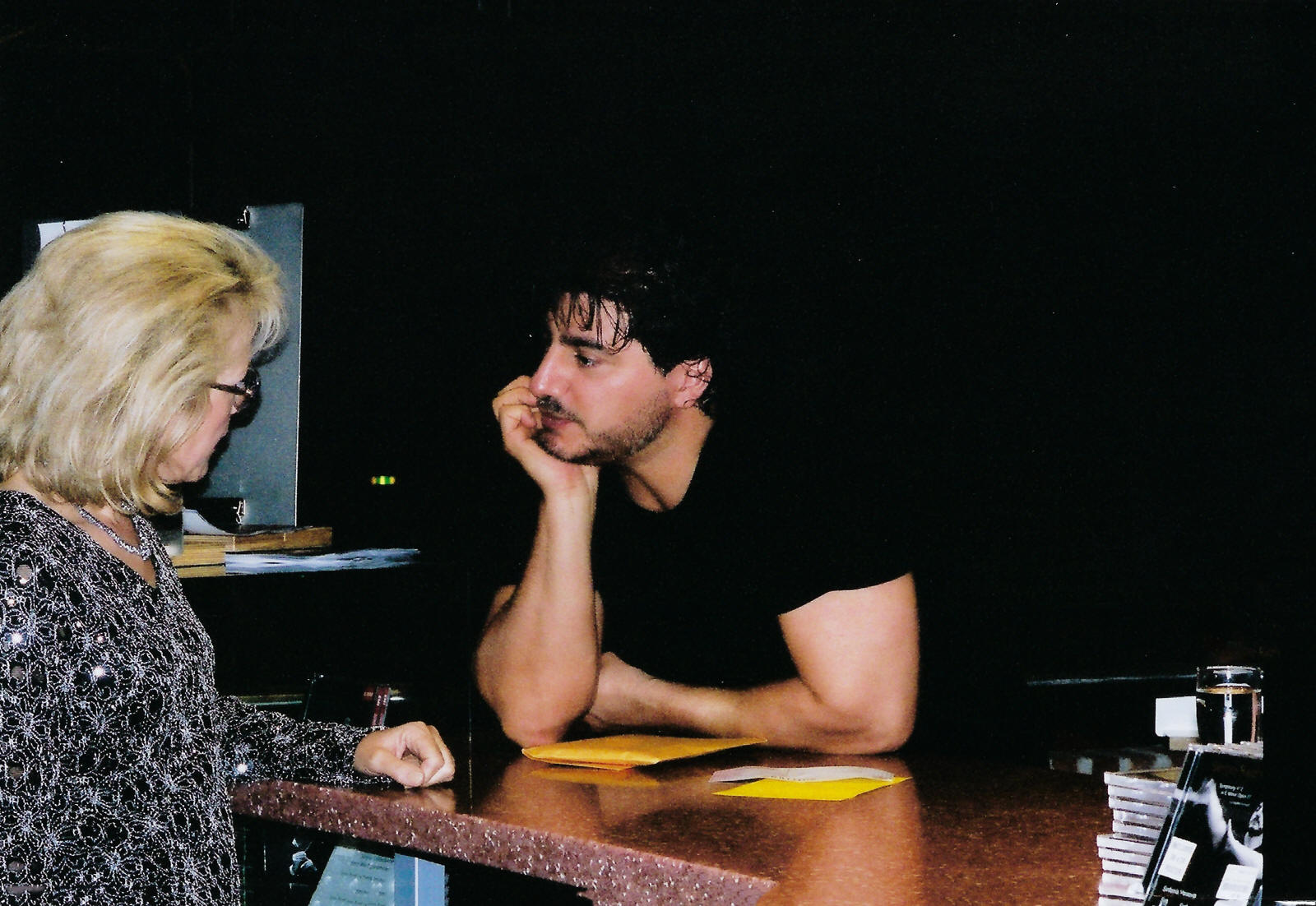

And our very first fan club luncheon!

|

|

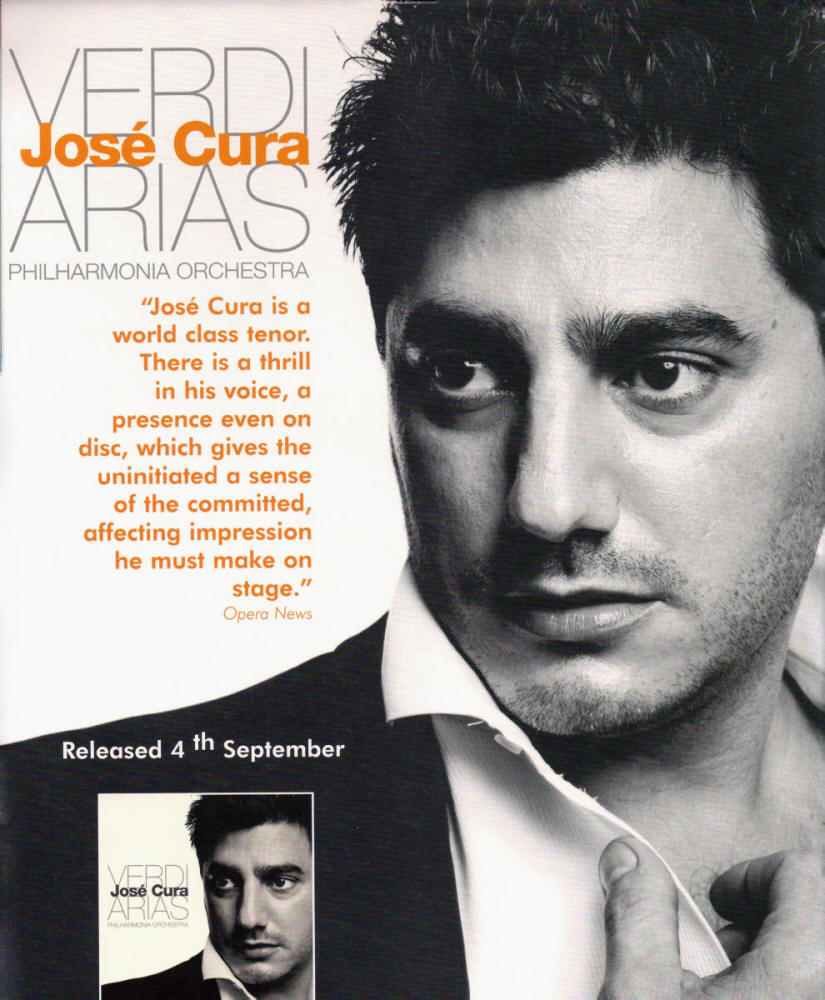

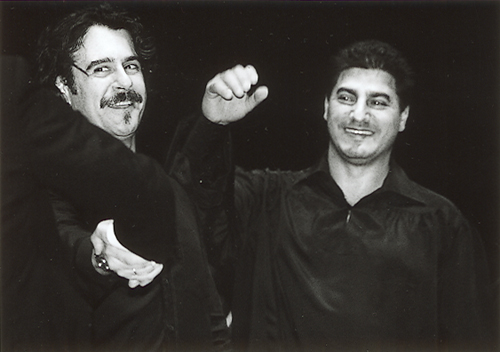

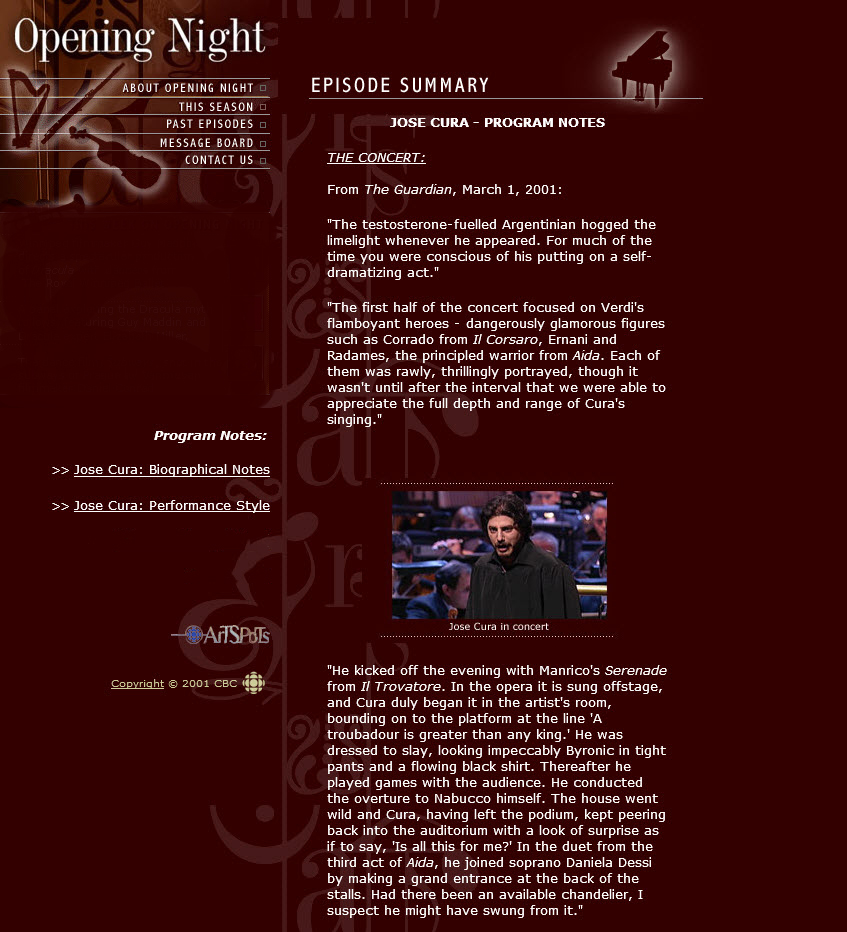

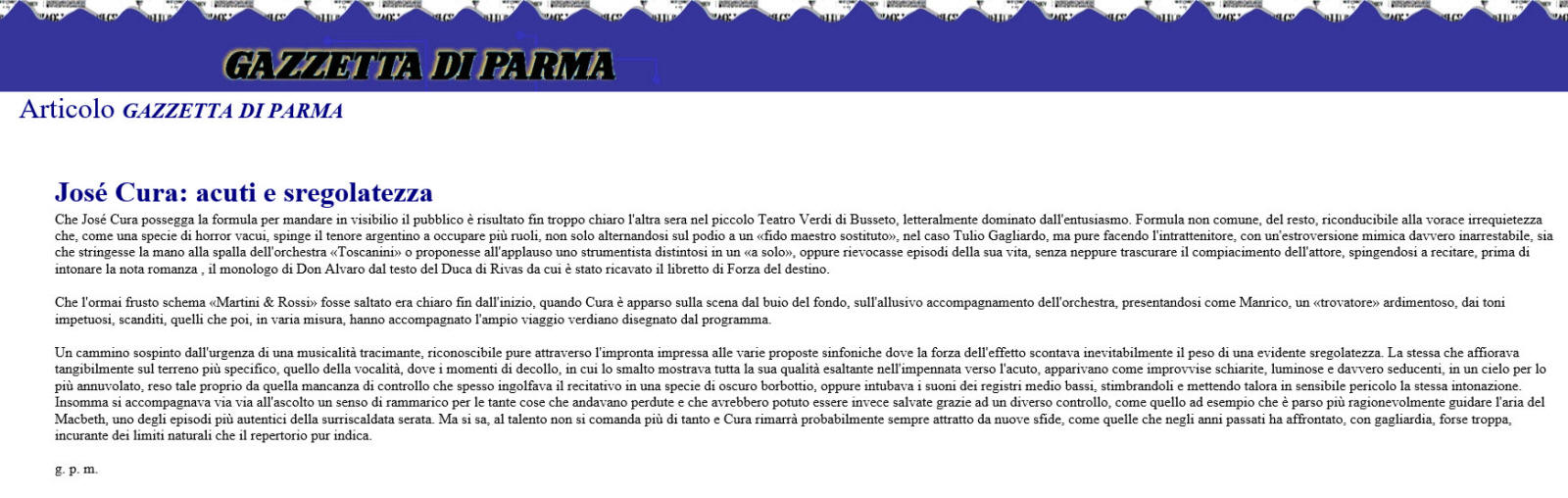

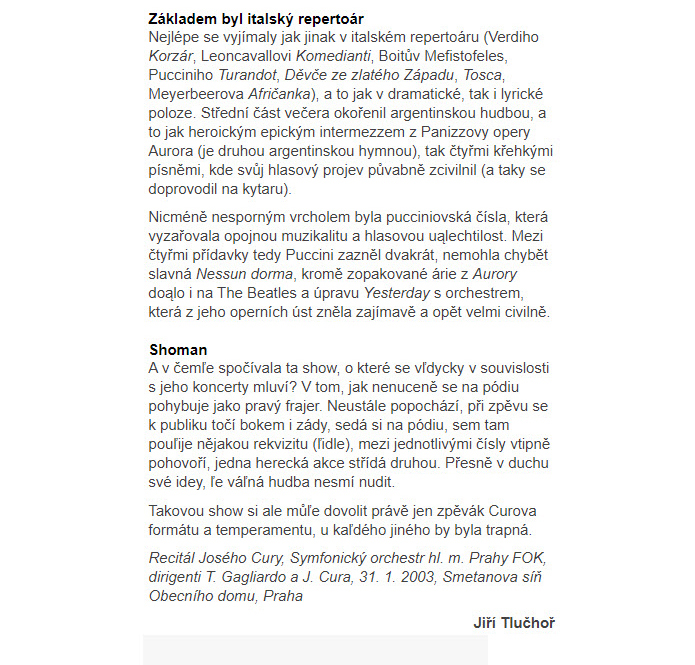

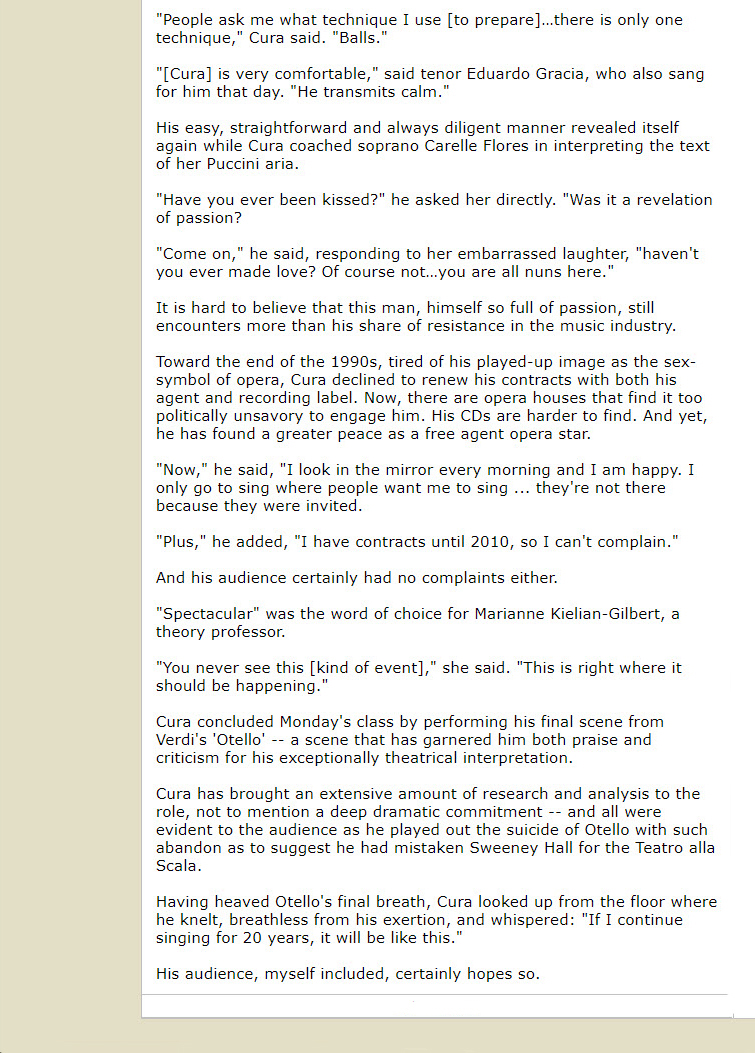

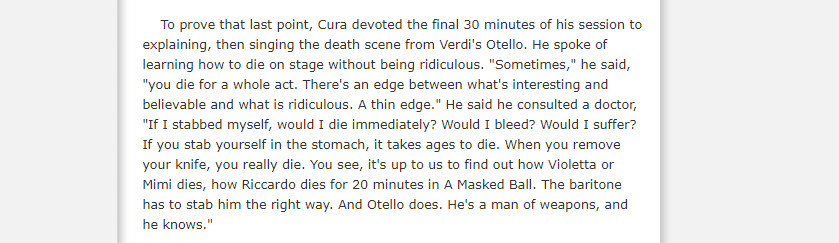

Amazing what a couple of tenors can get you Jose Cura/Carlos Alvarez | Royal Albert Hall, London Independent Nick Kimberley 18 September 2000 [Excerpt] The programme cost Ł8 for nine pages of relevant text, badly proof-read and with the musical running-order garbled. Well, the Argentinean tenor José Cura has an audience that extends beyond the confines of the opera house, and good luck to him. If the programme was a rip-off, you can't accuse "All-The-Way" José of ever giving less than his all. That is part of the problem; the relentless energy of his singing tends to overwhelm the music, especially in a concert of showstopping arias. Not that the show was all Cura. The first voice we heard belonged to the Spanish baritone Carlos Alvarez, who showed a powerful, dark-hued voice and properly idiomatic phrasing. For a baritone in Italian opera, that's half the battle. But where tenors are impetuous, ejaculatory, baritones must be thinkers. Instead, Alvarez blasted away with a monochrome timbre that the sound enhancement only emphasised. Later, he took the role of Escamillo from Bizet's Carmen, where swagger is mandatory, but still he lacked the necessary finesse, while his French was all but unintelligible. At least in duet with Cura there was genuine vocal empathy between the singers. Cura, though, was the main attraction. His first entrance was as theatrical as the context allowed: while the Philharmonia Orchestra played the introduction to "Vesti la giubba" from Leoncavallo's Pagliacci, he emerged from the wings, head hung low, shoulders stooped. Reaching centre stage, he put his hand to his forehead as if resigning himself to the worst that life could throw at him. Theatrical, then, but a mite exaggerated: rather like the voice itself. Cura is the real tenor article, with that Italianate ring that is so rare. He enjoys filling his chest for the big crescendos, which he manages with no apparent difficulty; and there were moments, in Don Jose's "La fleur que tu m'avais jetée" from Carmen, for example, when the timbre lightened, the head voice bringing a delicacy of colour. I can even take the sobs that he introduces here and there: they're a token of wholeheartedness. Too often, though, he's inclined to pump up the volume so that the lyricism becomes a fading memory, effaced by sheer vocal force. He's a big personality with a big voice, and no one would want to stand in the way of that. If only he would temper the largesse with a degree of restraint: but maybe that's not what tenors are for.

|

Cork and Dublin

|

|

|

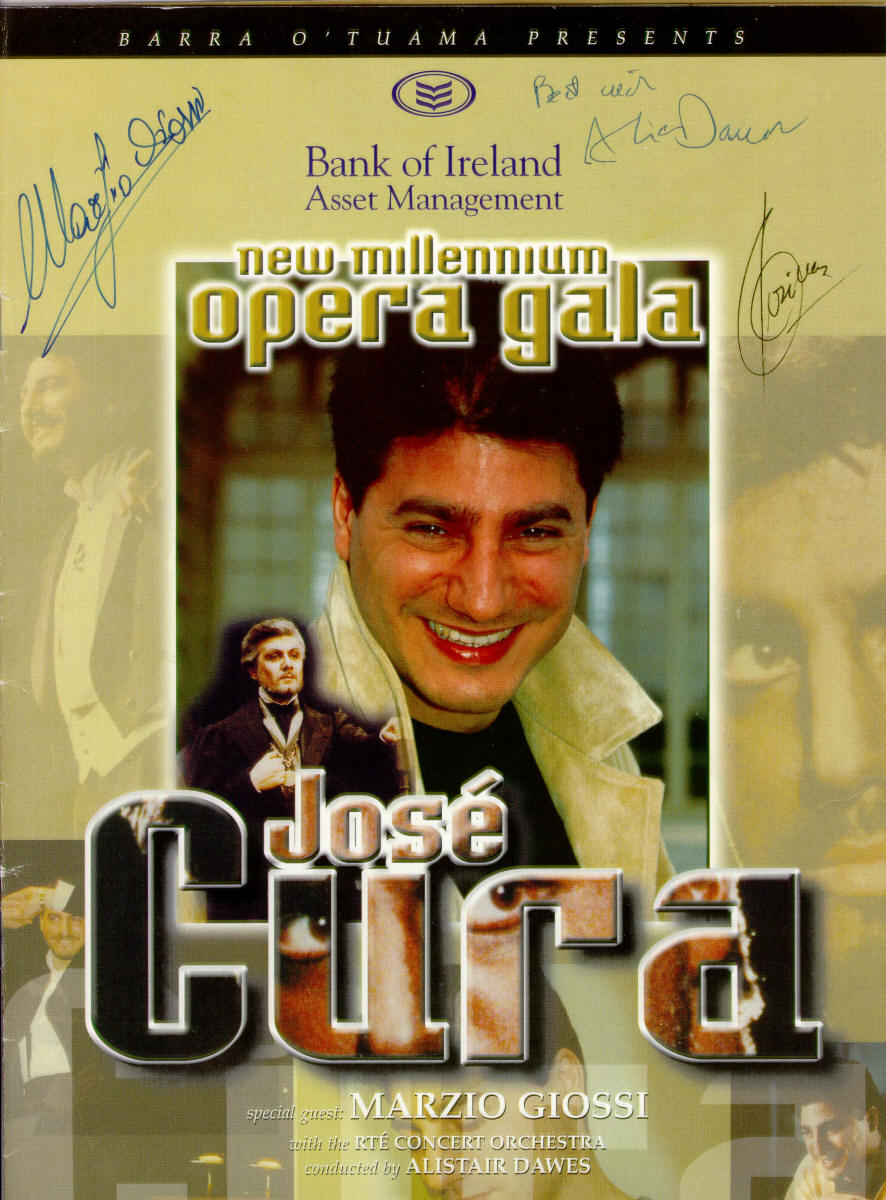

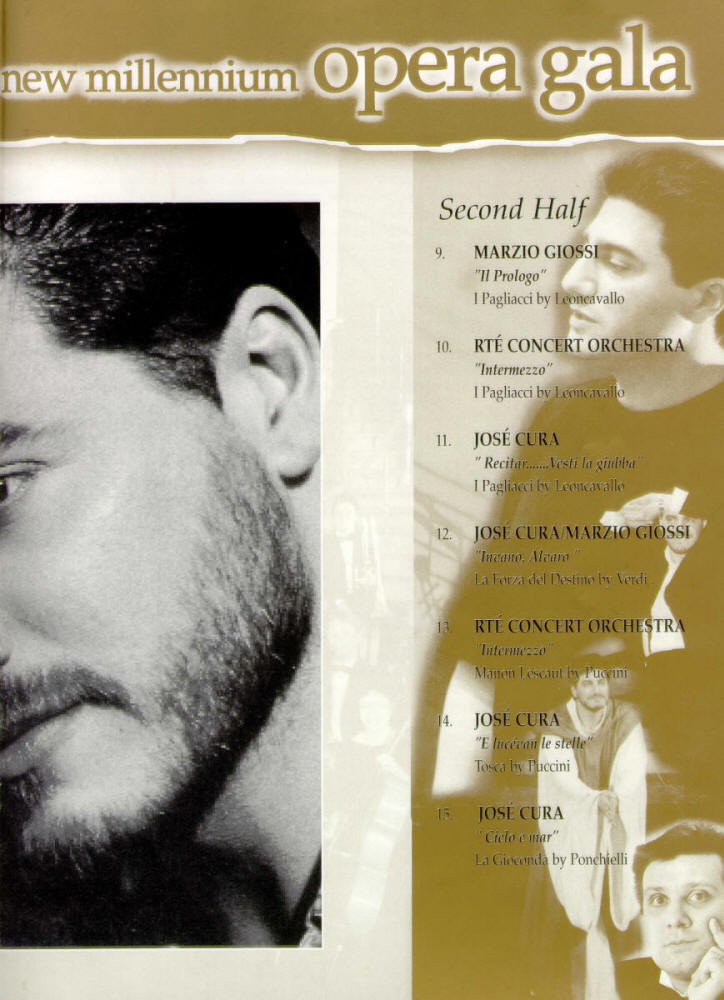

17 February 2000 CITY AND PORT OF CORK NEW MILLENNIUM OPERA GALA

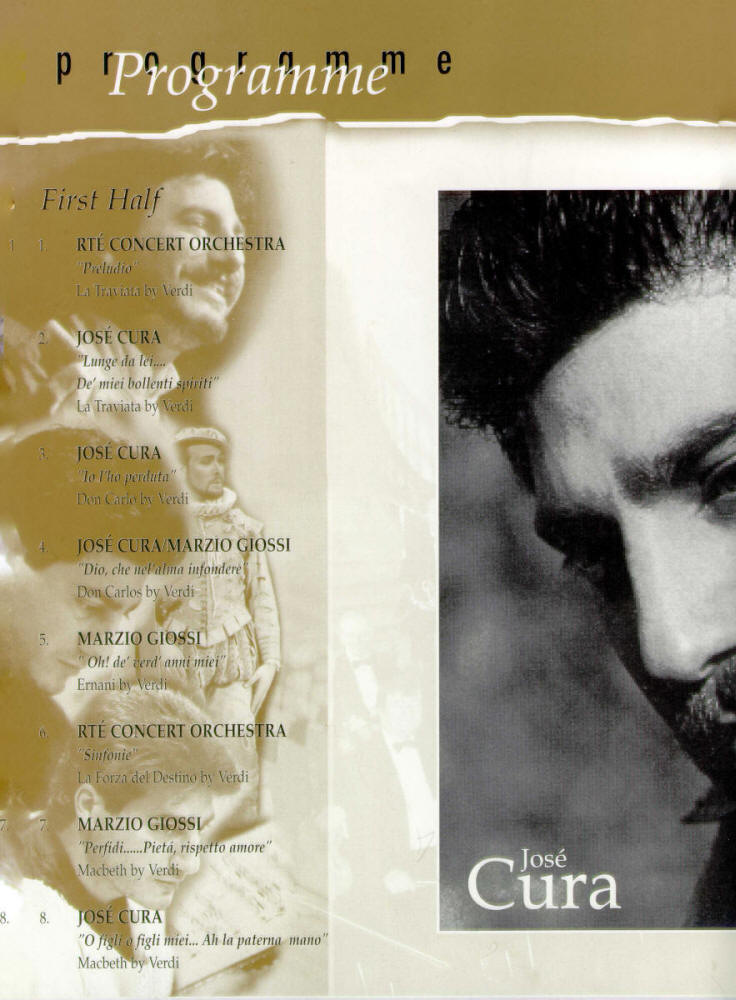

Cork Corporation and the Port of Cork have joined together as main sponsors to bring, José Cura to Cork City Hall, on Wednesday 20 September 2000. Now considered to be the No.1 tenor in the world, José Cura brings a dynamism and verve to all of his performances, unparalleled by his illustrious contemporaries. Sharing the stage in Cork with the great man will be the RTE National Concert Orchestra, conducted by Alistair Dawes and Special Guest, the well known Italian Baritone, Marzio Giossi, who is a great favourite with Irish audiences. The performance will be narrated by David McInerney. José Cura is now recognised by international critics as being the most important dramatic tenor singing on world stages today and is considered to be the tenor of the new Millennium. Cura is sought-after by every country in the world but he has kept a commitment to impresario Barra O’Tuama to come back to Ireland before the end of the Millennium. COMMENT BY LORD MAYOR

Mr. Frank Boland, chairman, Port of Cork, co-sponsors of the event said that he was delighted that Barra O’Tuama had attracted a truly world renowned artist to front a magnificent musical evening. He said the Port of Cork’s involvement in this sponsorship was a further tangible recognition of the wonderful support which they receive from industrial, commercial and social groups in the South West and neighbouring counties. He has sung in all the great opera houses of the world including Convent Garden, Metropolitan Opera New York, Vienna, La Scala, Verona, Rome Turin, Trieste, Palermo Torre del Lago and many many more. Before coming to Cork José will sing Otello in Washington, Pagliacci in Bologna, Otello in Munich and will star in an outdoor world-wide live television performance of La Traviata which will be televised on location in France. In the week prior to his Cork performance he will sing a concert at the Albert Hall in London. José has already recorded a new CD of Verdi arias which will be released in early September and it is believed that this C.D. will be a world top seller. His special guest is Marzio Giossi who has sung in all the great opera houses throughout Europe and the U.S. Marzio has been acclaimed as being one of the finest baritones to emerge from Italy in recent times. He has previously sung with José Cura in Fedora in Trieste and José asked specially for Marzio to be his guest due to his popularity in Ireland. This performance at the City Hall will be supported by AIB Bank, Beamish & Crawford, Murphy’s, Sunday Independent, The Examiner, RTE etc. The city and port must be congratulated on such a coup for Cork as it will be the first time that the top tenor in the world, in his prime, will sing in the city.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20ed.jpg)

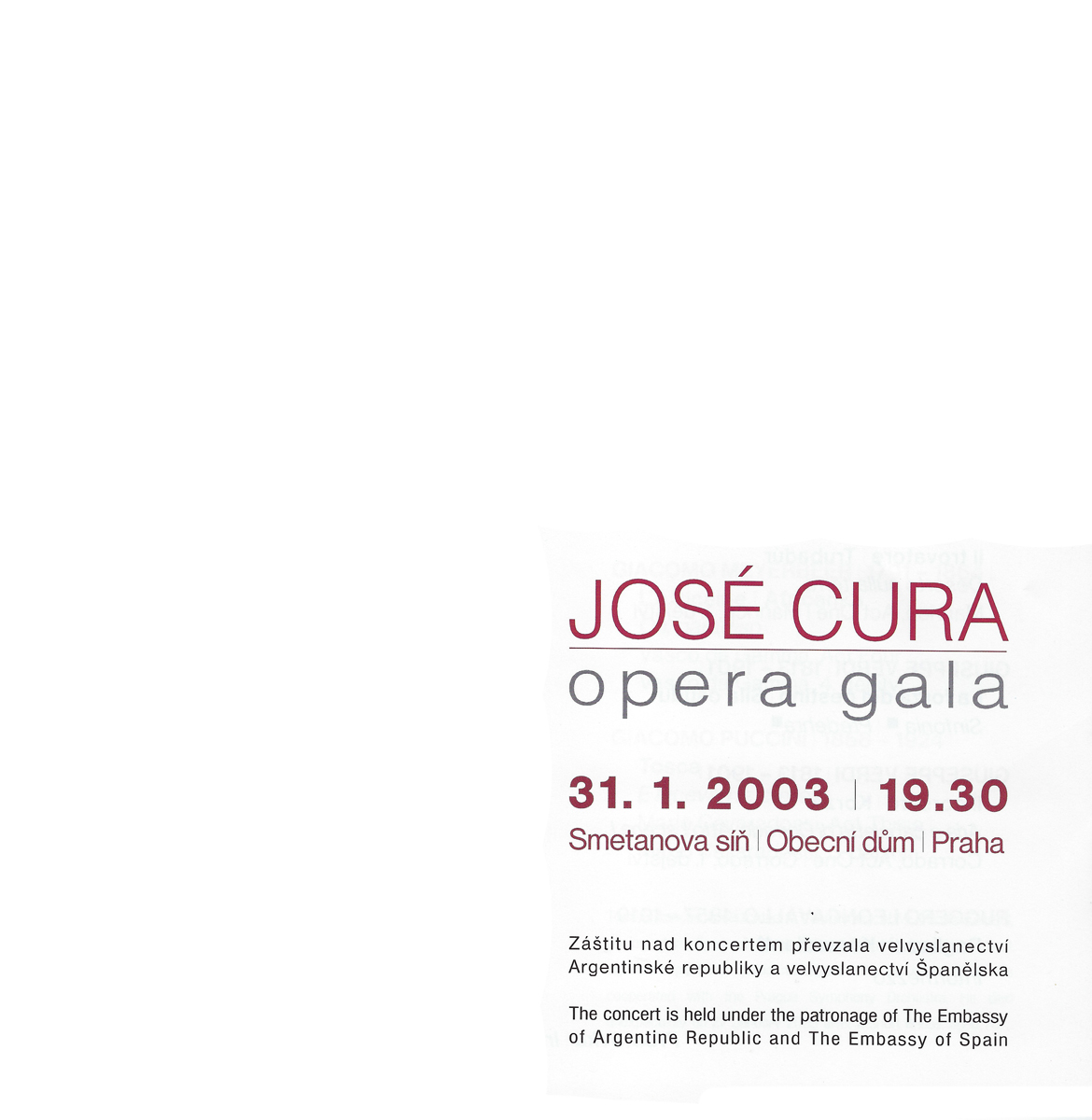

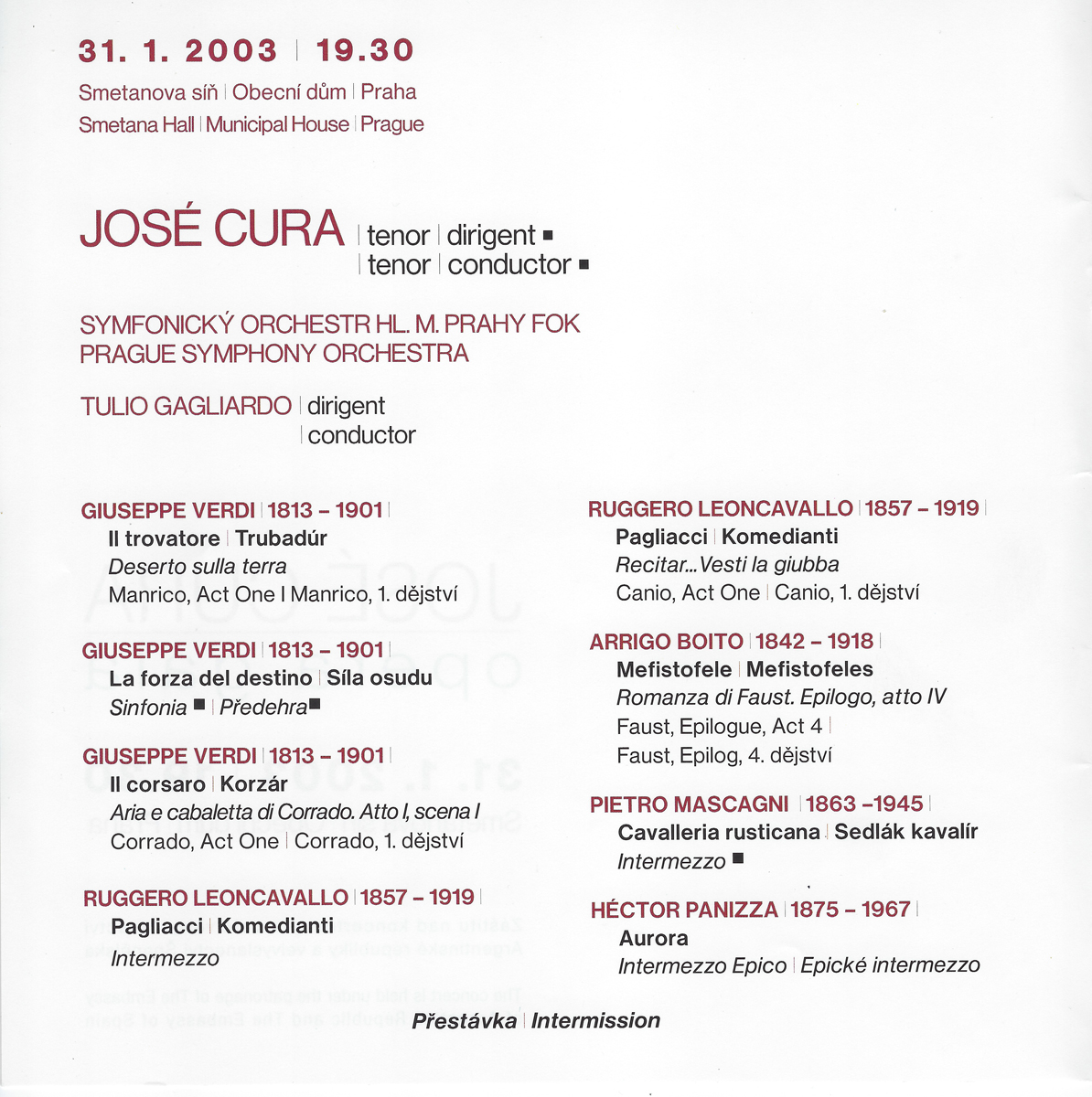

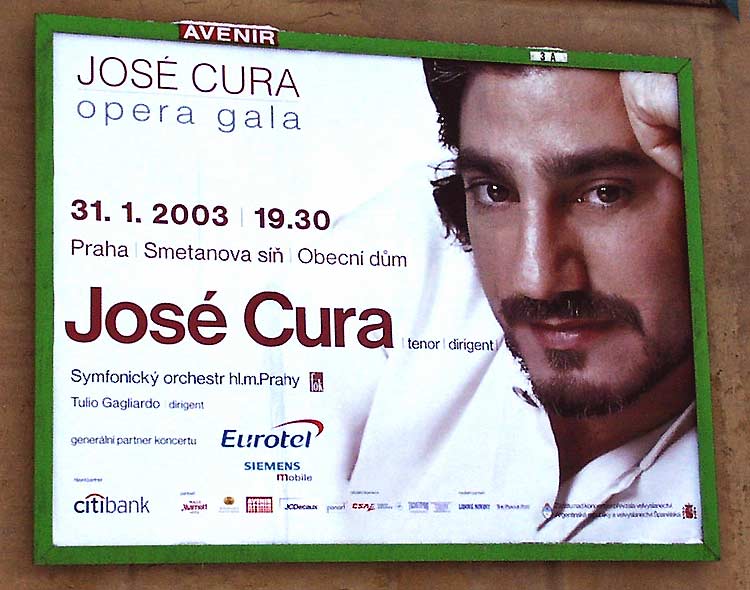

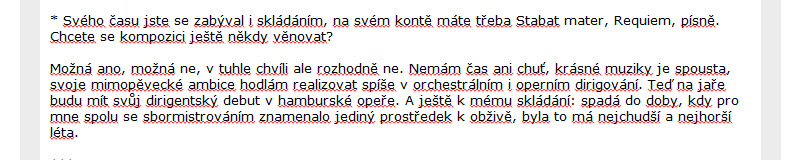

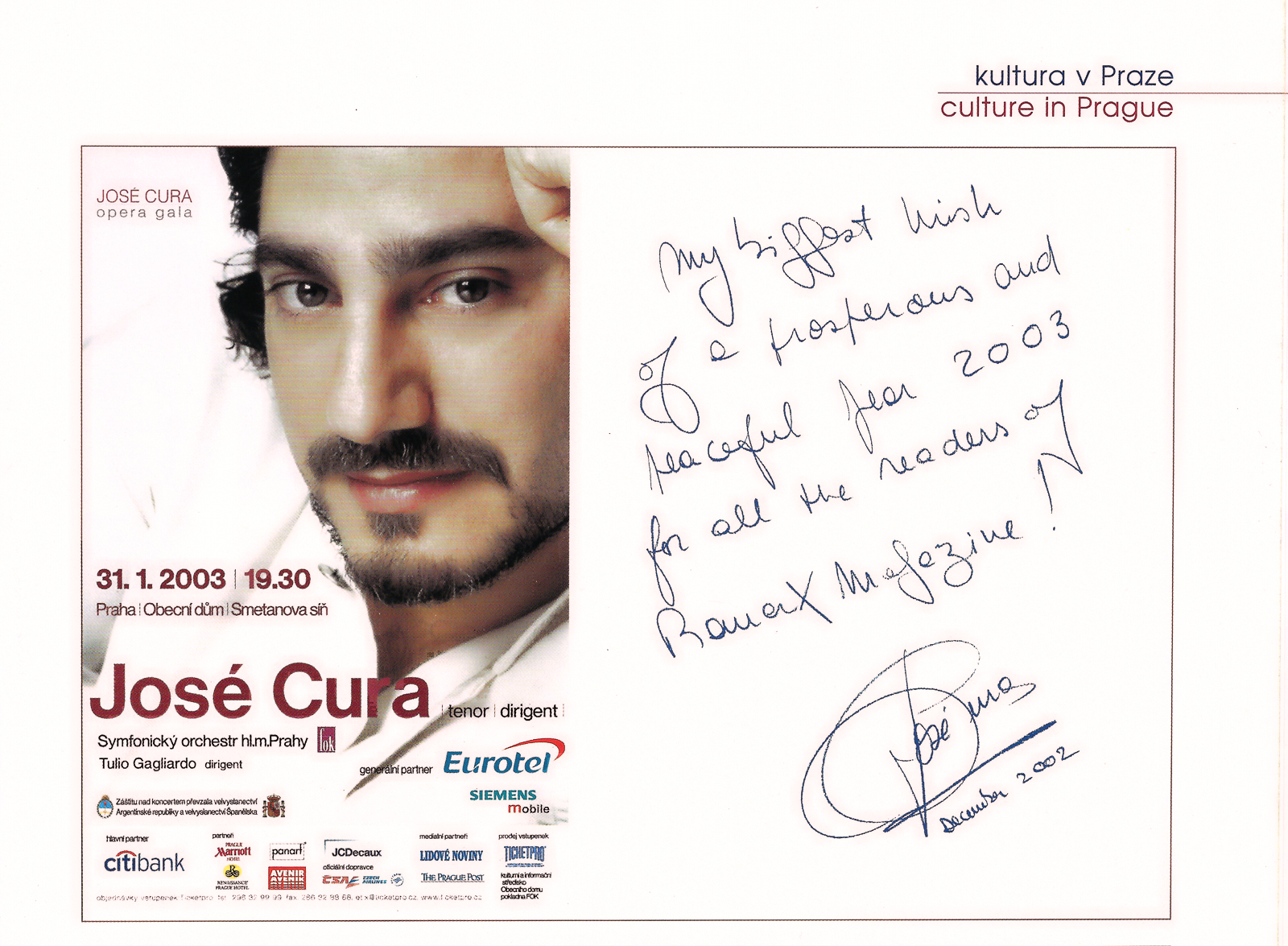

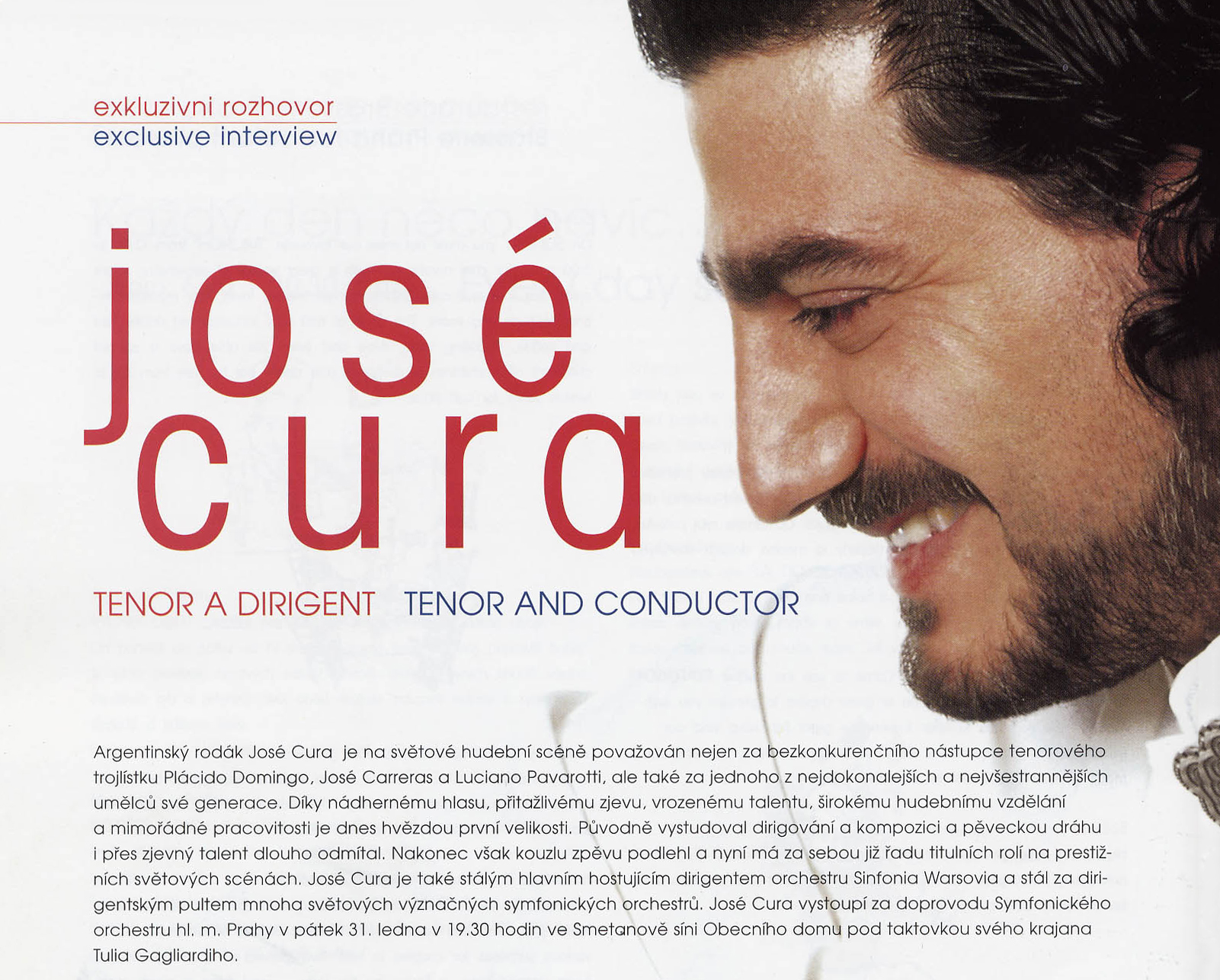

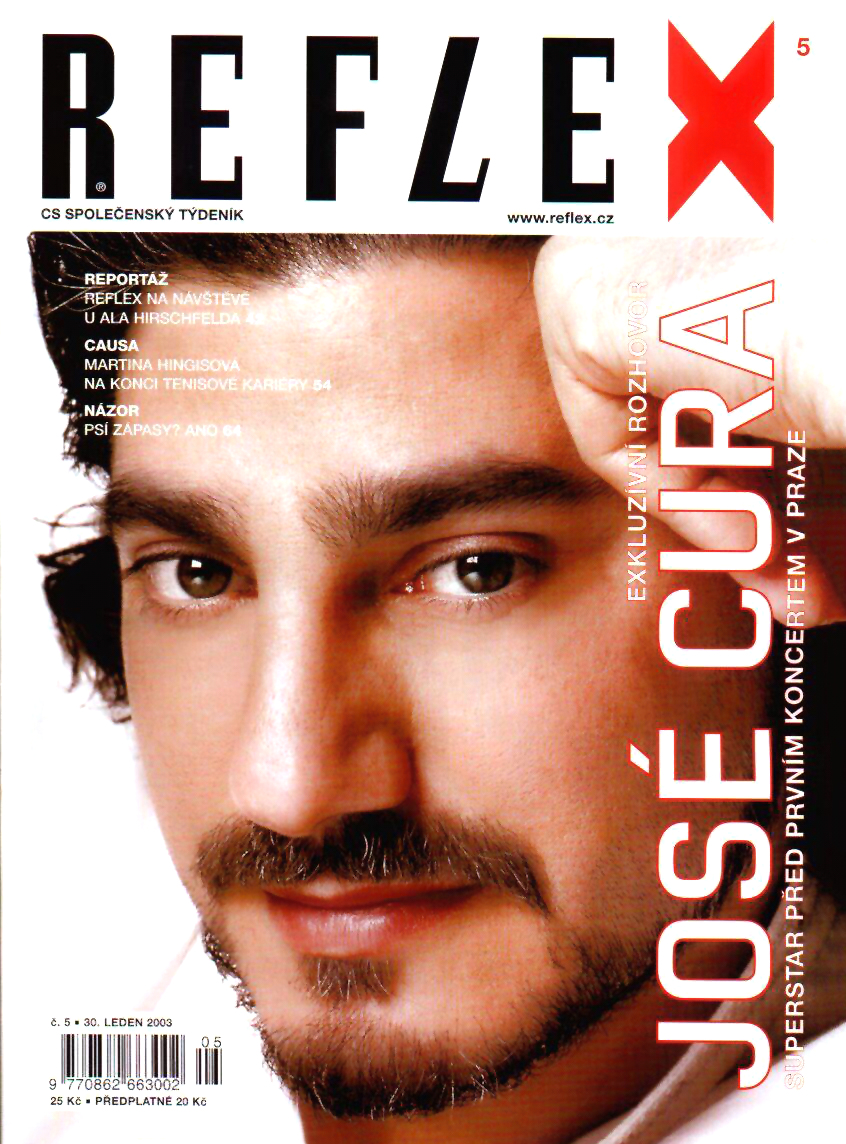

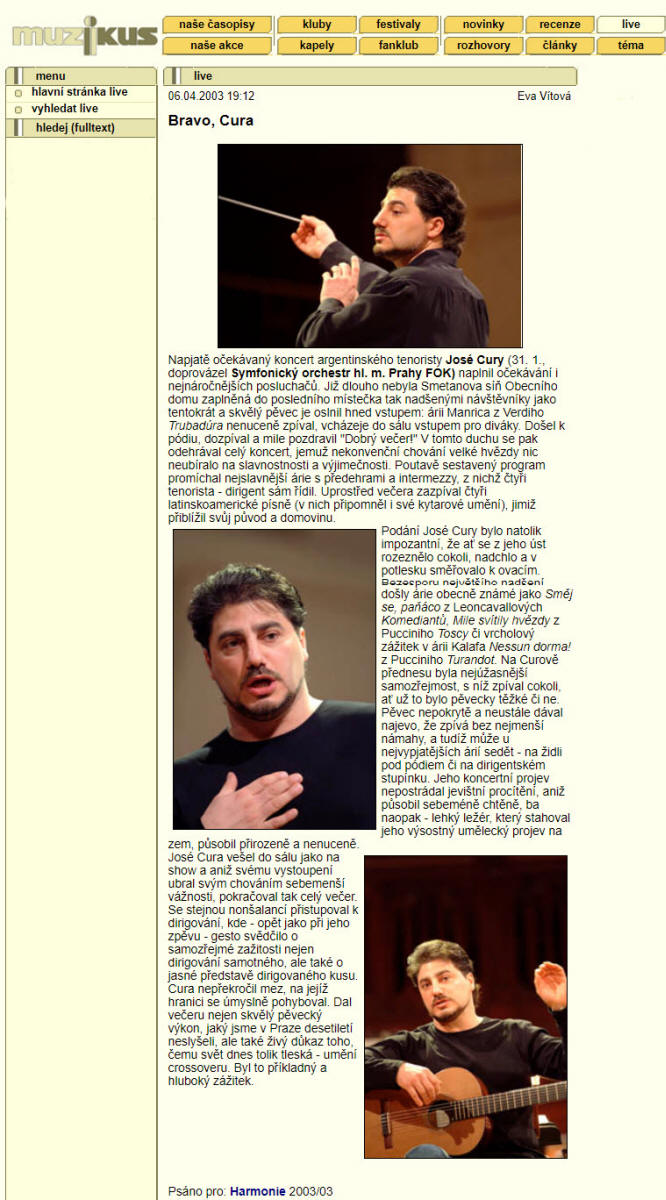

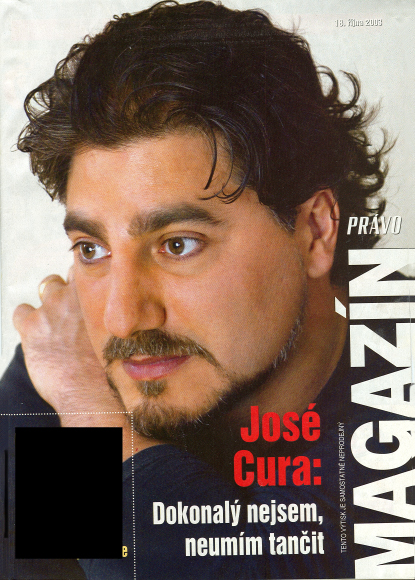

PRAGUE,

Jan 29 (CTK) - None of the three most

difficult roles named by internationally

renowned singer José Cura is an opera

character. The forty-year-old Argentine

tenor, who describes his life as traveling

around the world as a gypsy, considers

the role of husband, father and dog

owner the most difficult.

PRAGUE,

Jan 29 (CTK) - None of the three most

difficult roles named by internationally

renowned singer José Cura is an opera

character. The forty-year-old Argentine

tenor, who describes his life as traveling

around the world as a gypsy, considers

the role of husband, father and dog

owner the most difficult.

.jpg)

PRAGUE

PRAGUE

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%203.jpg)

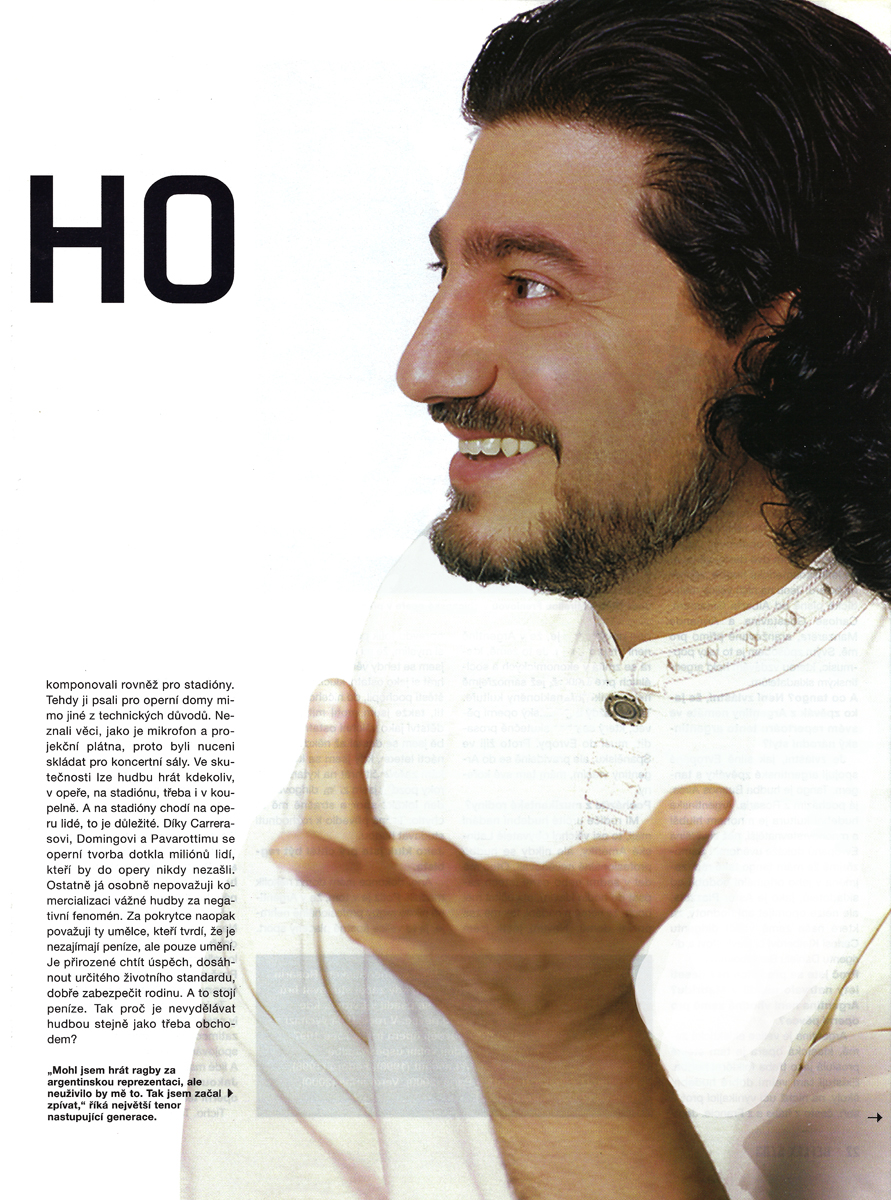

How

did you, a tenor who excels in the flamboyant

roles of the Italian repertoire, break

down these intimate songs?

How

did you, a tenor who excels in the flamboyant

roles of the Italian repertoire, break

down these intimate songs?

.jpg)

"It

is certain that they are a race

apart, a race that tends to operate

reflexively rather than with due

process of thought."

"It

is certain that they are a race

apart, a race that tends to operate

reflexively rather than with due

process of thought."

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)