Carmen @ La Scala

Low voltage Carmen in Emma Dante's return to La Scala

Bachtrack

30 March 2015

This is the year of Milan's Expo - the international Summer exhibition on everyone's lips - for which La Scala have extended their season and pulled some old productions out of the wardrobe. Emma Dante's Carmen received a famously mixed reception at 2009's season-opening performance from press and public alike. Barenboim assured it would become "a legend production", whilst traditionalist opera director Franco Zeffirelli claimed that it had caused him to see the devil.

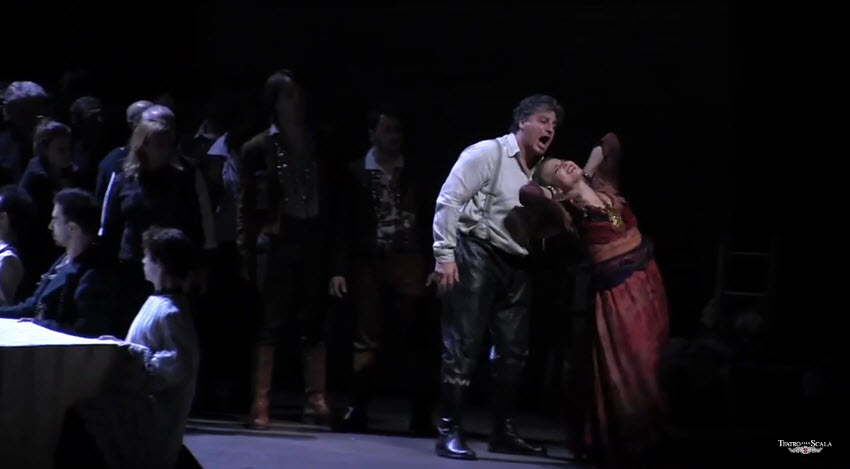

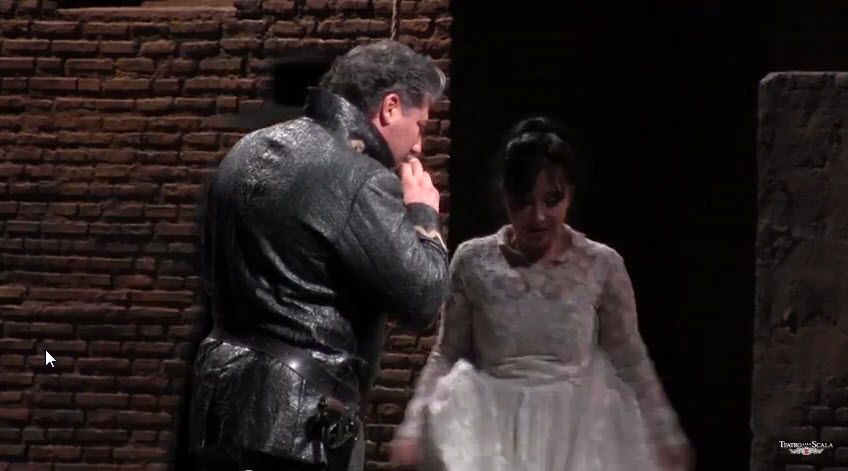

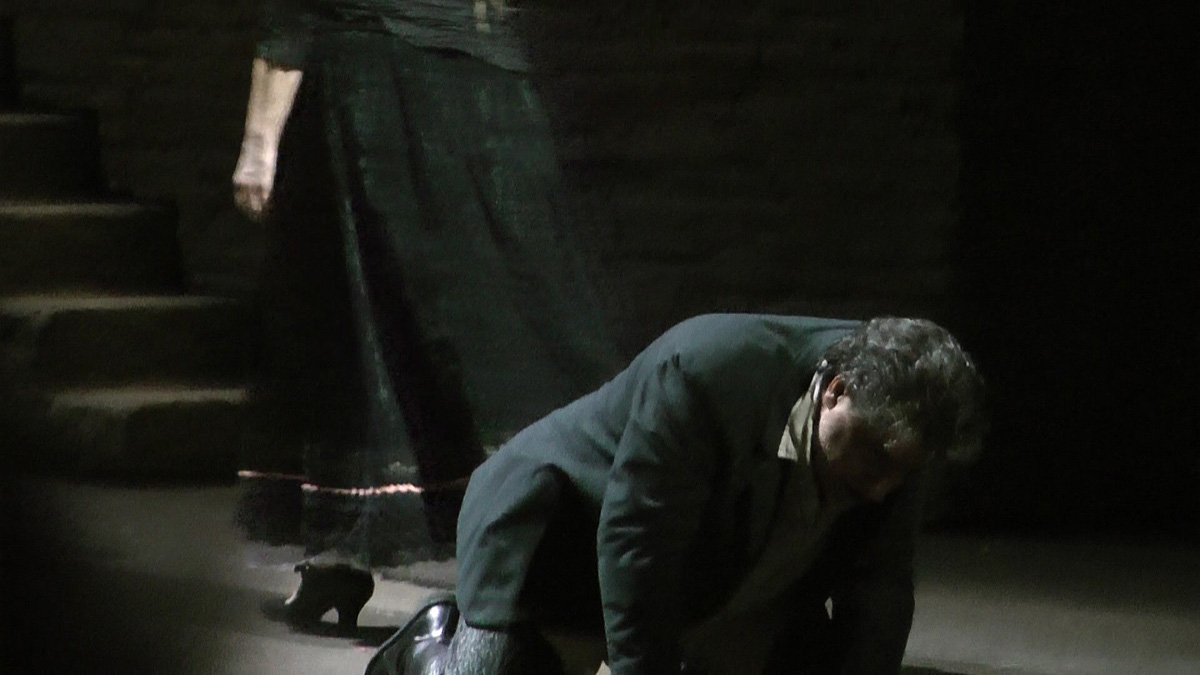

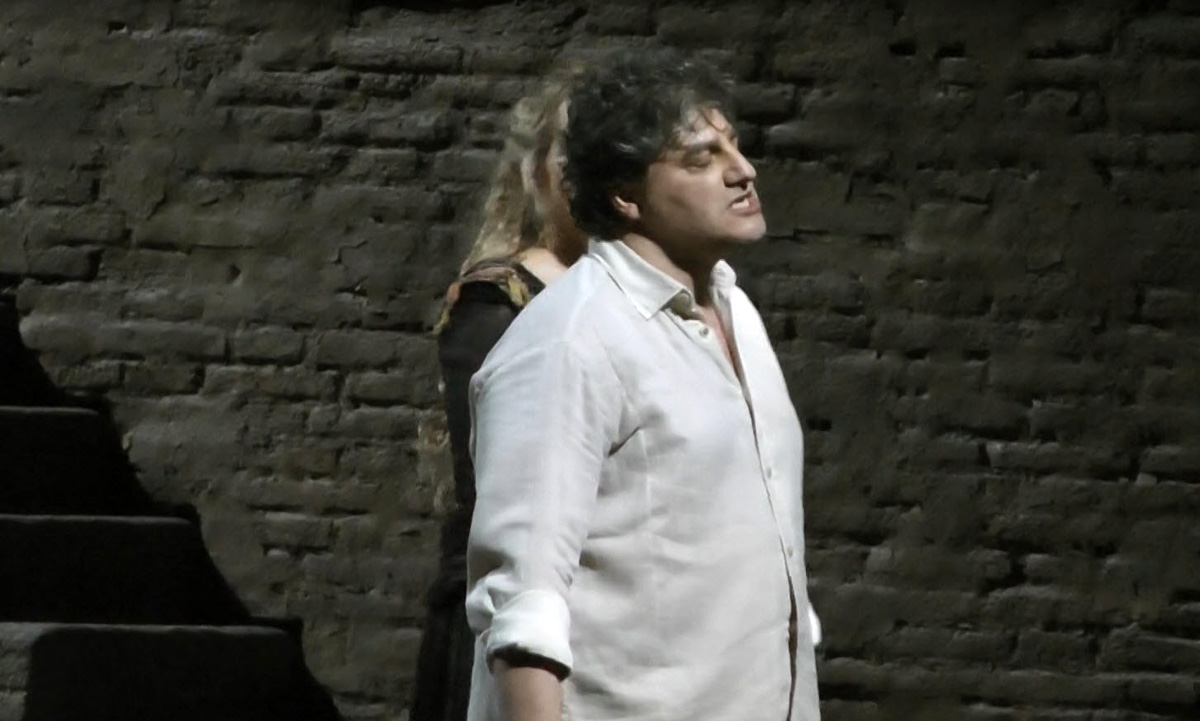

This year's version remains largely intact, though the original star-studded cast has received an overhaul. There was often a lack of chemistry between tonight's leading roles this time around. Elīna Garanča's blonde Carmen possesses an innocent streak, and her cheery "Habanera" lacked the necessary sass to get our pulses racing. José Cura's Don José is world-weary and seemingly old enough to be Carmen's father - impassible and often immobile, he hardly flinched when Micaëla relayed news from his dying mother, sweetly conveyed by Elena Mosuc as this was. Such a low voltage rapport between the main characters made it difficult to buy into the plot's tragic developments or the various directorial quirks. In a reversal to conventional practice, Carmen rather than José plunged the dagger into her heart at the work's climax, which was a somewhat implausible feature when there had been so little in the way of a dramatic buildup.

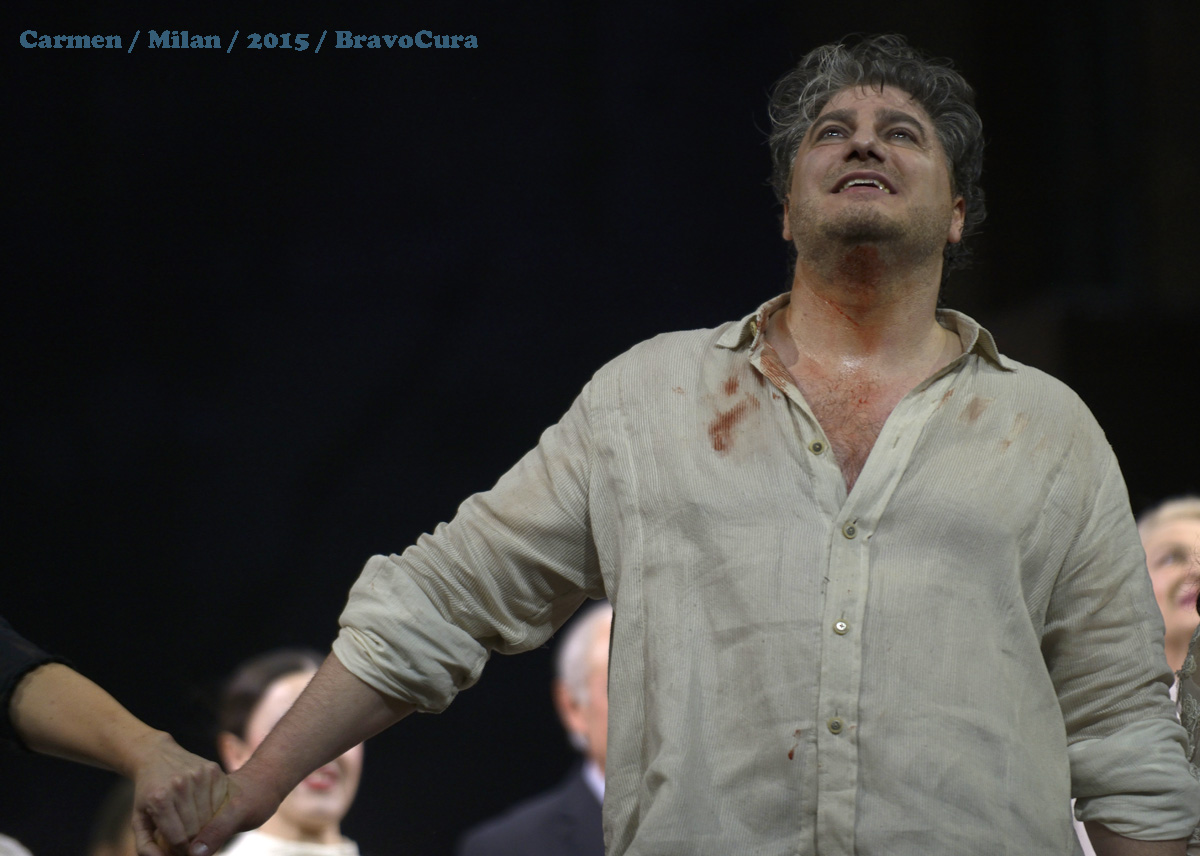

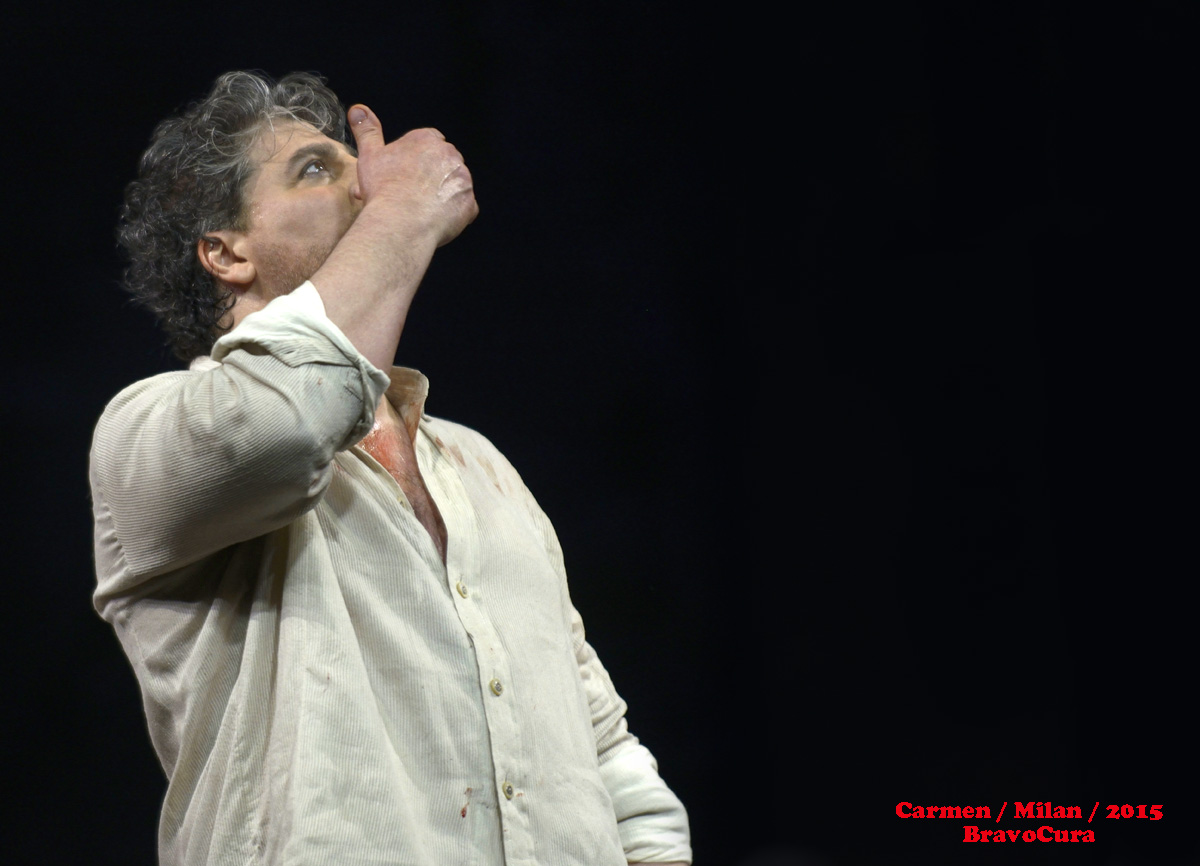

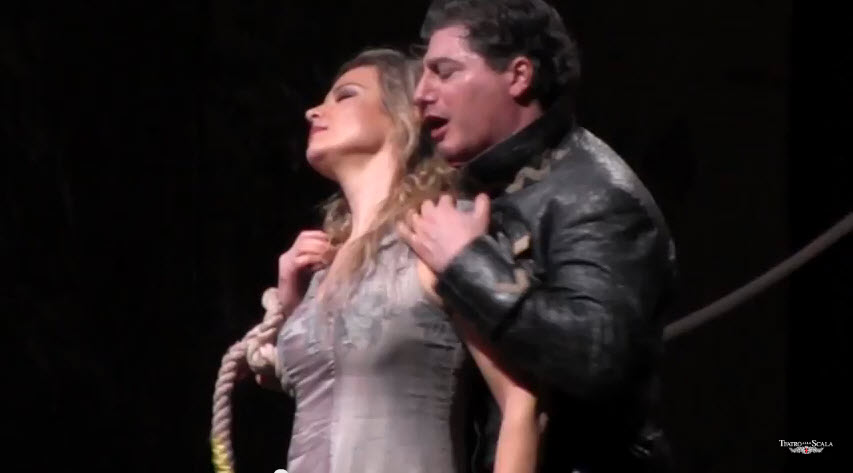

But in spite of these weaknesses, there were moments where the characters' relationships started to kindle. Carmen ensnared her captor José with a hazy "Tra la la", entangling him in the suspended ropes that bound her arms, and the tension bubbled in a candelabra littered Lillia Pastia's, with José tormented and Carmen burning with resentment at his refusal to desert the army. There is by now some wobble to Cura's voice, but he is capable of shifting cleanly through the gears to find an emotive range.

Massimo Zanetti, a dapper silver fox of a conductor, overflowed with energy, and we might have wanted him to steal through the texture more often to provide some oomph. The prelude to Act III had utter poise, whilst that to Act IV brimmed with joie de vivre and all the zest of Seville oranges: smouldering strings, lippy brass and rapping tambourine. And there were also heart-warming contributions from gypsy swashbucklers Frasquita and Mercédès, charmingly conveyed by Hanna Hipp and Sofia Mchedlishvili respectively. There is impressive depth and sheen to Mchedlishvili's voice who, like her fast-rising compatriot Anita Rachvelishvili, is a product of the La Scala Academy.

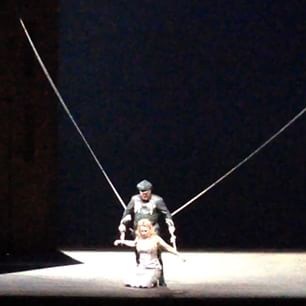

A much bigger problem in this production than casting or individual performances was posed by the direction and scenography. Dante shares with Zeffirelli his penchant for buzzing, bustling sets, which was easy on the eye in the case of Act I's heaving piazza with marching children, trinket flashing gypsies and a woman giving birth. But incongruities between the sets cause disorientation when we switch to a geometric blankness for Act III's mountains, or to Act II's Lillia Pastia's Inn in an underground lair, borrowed from a James Bond villain perhaps, where a slowly descending dumb waiter didn't allow Escamillo the most imposing entry. Without grounding in time, place or a coherent aesthetic, the narrative is left to flap helplessly in the wind.

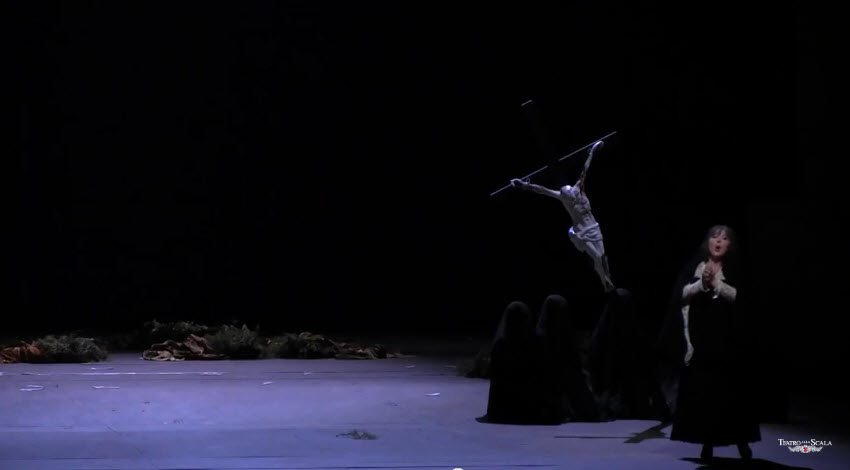

In particular, Dante has the tendency to clog the drama with cloying symbolism. Religious imagery abounds, for example with a hearse crossing the stage to spell out Carmen's imminent death from the off. When factory girls dressed as nuns disrobe to nightdresses before frolicking in a steam-filled fountain, we are unsure whether we are supposed to feel aroused or amused. Far from sharpening our focus, the symbolism tends towards the obscure, and it is often gratuitously nauseating, so that watching bloodied factory girls kicked into the air by raving soldiers made for an uncomfortable sitting. It was surely no coincidence that moments of dramatic clarity coincided with respite in the stream of allegory.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Carmen Bleeds but Passions Die

Random Thoughts / BravoCura

A contradiction at La Scala: Carmen, an opera that explodes with passionate music, provocative women, and testosterone-fueled men remained stubbornly listless with a production that inundated the stage with red but remained curiously bloodless. Emma Dante’s directorial concepts were ill-conceived and implemented with such heavy-hand that they both overwhelmed and undermined Bizet’s slender drama. Not even the formidable talents of José Cura and Elina Garanca were able to salvage the evening.

Carmen is not the story of the Catholic Church stalking a deviant spirit who threatens the conservative teaching of the institution, driving the gypsy to suicide and ending with a smug, congratulatory procession; this is pure invention by Dante. To introduce original elements to a work requires the director find a way to form visceral connections and create the cause and effect that illuminate the plot; that was missing in Dante’s retelling. Instead, we had inconsequential busywork filling the stage at inappropriate times, gratuitous violence and passionless passion. The tragedy of Carmen and Don José is superseded by the triumph of the Church.

Carmen is not a feminist manifesto, and feminism is not an excuse for women on women violence or men on women violence—such activity is never a cause for levity. Act I featured a fight between women which concluded in near slapstick hair pulling, wild, bizarrely exaggerated faces, choreographed flips to display panties and enough blood to mark the stage floor for the rest of the opera, followed by male guards brutalizing a prone woman. Nor does feminism function as a means to introduce pre-pubescent girls into prostitution, which this Carmen appears to do.

Carmen is not about the emasculation of men; Carmen’s excess does not depend on Don José’s constraint. In truth, Carmen is a shallow character who dominates with catchy music and provocative lifestyle but her pursuit of freedom covers an adolescent refusal to accept responsibility. In most productions, her superficiality is compensated with exploitive sexuality but in Milan even that aspect was blunted: this Carmen was more flirt than vixen, more tease than temptress, more innuendo than heat. And Dante’s Don José, the character with the most complicated music and the most persuasive developmental line in the opera, was turned into a cipher, leaning passively against a wall or sitting passively against a stone for swatches of time. He was never allowed to generate the prerequisite carnal heat usually associated with the character's motivation: in Act II, after release from prison, his initial sexual encounter with Carmen consisted of taking off his jacket and slowly rolling up his shirt sleeves--certainly not the actions of a man in need of sexual release. Cura did manage to reclaim some dynamic control by killing Carmen rather than allowing her to commit suicide (as dictated by Director Dante in her notes) but the impact of his desperate act is immediately lost in the distraction of the Catholic procession which, unfortunately, left Don José once more passively off to the side.

In short, the director reinterpreted Carmen and created a fatal imbalance between opera and director, between storytelling and ego, between Carmen and Don José. Nothing the two leads could do could undo the director’s conceit. How much better the evening would have been had Dante simply stuck to libretto and trusted the instincts of her stars.

Next week: an act by act recap.

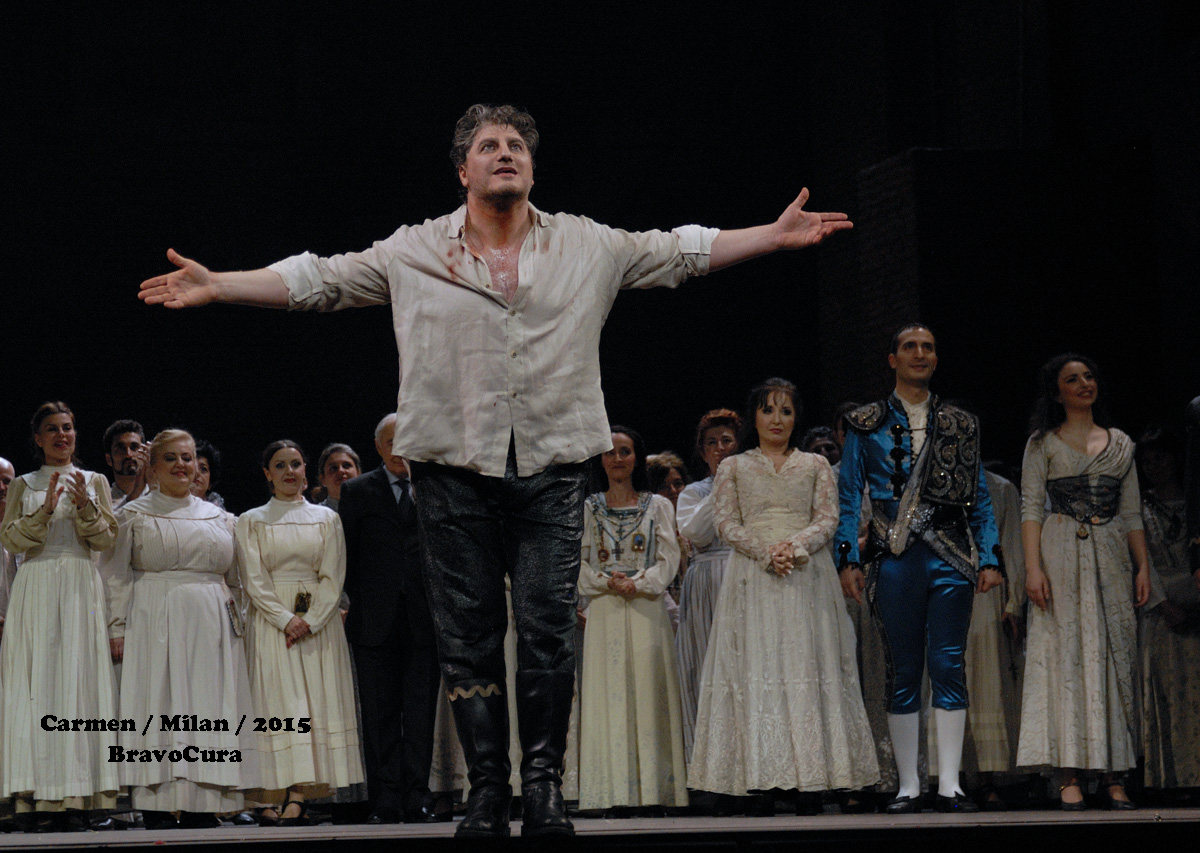

About La Scala

The performances in this production, despite the directorial overreach, were world class and probably in any other theater in the world the singers would have been celebrated with standing ovations and unending applause. In Milan, everyone got booed (some more than others). The bulk of the disruption came from the ‘cheap seats’ [loggia] where a group of folks gather to boo—that is all they do and all they come to do. Depending on where you sit, you hear them as overwhelmingly loud or not at all; sadly the artists on stage hear them all too well. The booing has nothing at all to do with the quality of the performance but the mentality of a small group of La Scala regulars. It should be a huge source of embarrassment for the theater and they should move to limit or reduce the nuisance booer (and those who are paid to do so) but on some level we sensed management encourages it and may even take some pride in it.

La Scala is the typical horseshoe auditorium. Orchestra stalls are fine and recommended if you can afford them; they at least allow good sight lines. The boxes on the side walls are narrow and deep: if you go, do anything you can to avoid any seat in the boxes on the side except front row (boxes more toward the back may have better options). Anything else is an expensive ticket for standing room only. I was in third balcony, third box first row seat, stage right. My knees were jammed into the partition and the lady in the front row seat beside me kept asking for more room—there was no more to give. From my perch I could see half of the stage—and that was craning over the body of the lady in box 2 next to me who was lying across the railing and obscuring a lot of stage with head and shoulders (she was just trying to see as well). The two people behind the front row had to stand the entire opera and lean over those of us in the first row, making the box even more hot and stuffy than it already was. It was not a pleasant experience and both music and body suffered as a result.

But at least I had it better than Kira, who was in box 5 in balcony 2, stage right. She was in the second row (the theater sold out for this performance within ten minutes so we took the seats we could.) Although she was lower down and further back, from her seat she had absolutely no sightline to the stage. At best, she could see the first balcony on the other side and a glimpse of the curtain, stage left. The theater is obviously aware this is a completely blind seat because in a four seat box they added a fifth, behind the other second row person. By standing or kneeling on that fifth seat and dodging the bobbing head of the standing woman in front of her, Kira could see less than half of the stage some of the time.

Which brings us to sound. La Scala has an international reputation as an opera house so one assumes the sound quality would be spectacular. We had one performance in the orchestra stalls and the sound was fine—certainly not spectacular but all right. Once we got to the boxes, however, that changed. Certainly front row was satisfactory but the back row in box five was so far back in a narrow space that sound was muffled and muddy; not only did it have to find its way back to the ears but it had to survive the heavy paneling of the walls. That we were paying high price for what turned out to be a dead zone (visually and aurally) was a huge disappointment.

A couple of other things of note: La Scala has the most bizarre refreshment process we have ever experienced: you have to stand in line at the cashier to order and pay, then you have to stand in another line to get your order. With hundreds of people milling around and jockeying for attention during a 20 minute intermission, it seems pretty impossible to succeed—especially if you have to visit the restrooms (good luck!) during the same break. We gave up and assumed some people paid for refreshments they were unable to get. Also, La Scala programs for each performance are quite expensive (15 Euros per book, compared to 5 Euros at most other theaters) and the photos contained in the programs weren’t even from the current production.

Bathroom facilities are limited and rather than expand stalls the theater has introduced unisex stalls. A solution but perhaps not the best.

We were absolutely disappointed in our first, and perhaps last, trip to this famous theater. The facilities are below average, the acoustics are no more than average, and even with an excellent production with extraordinary singers, the people in the balconies who live to boo ruined the experience. We would rate the experience as horrible if not for the wonderful effort of the musicians who deserve combat pay for enduring their stay in Milan.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)