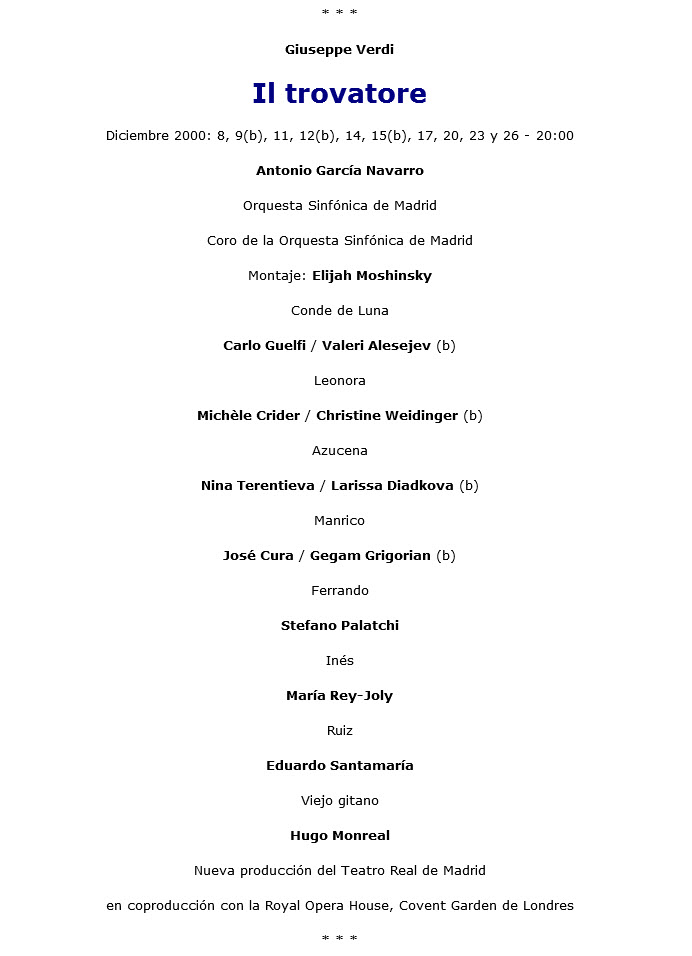

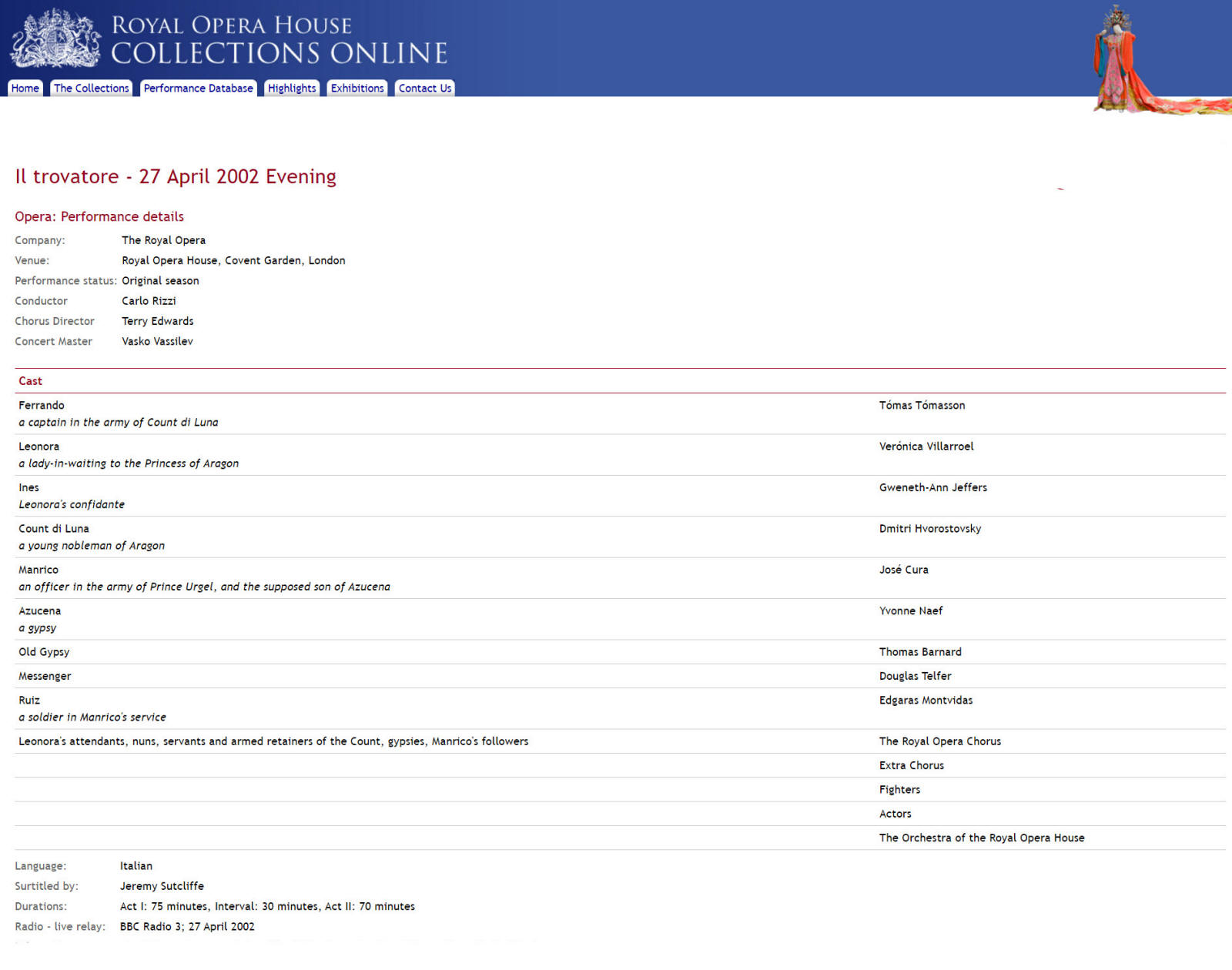

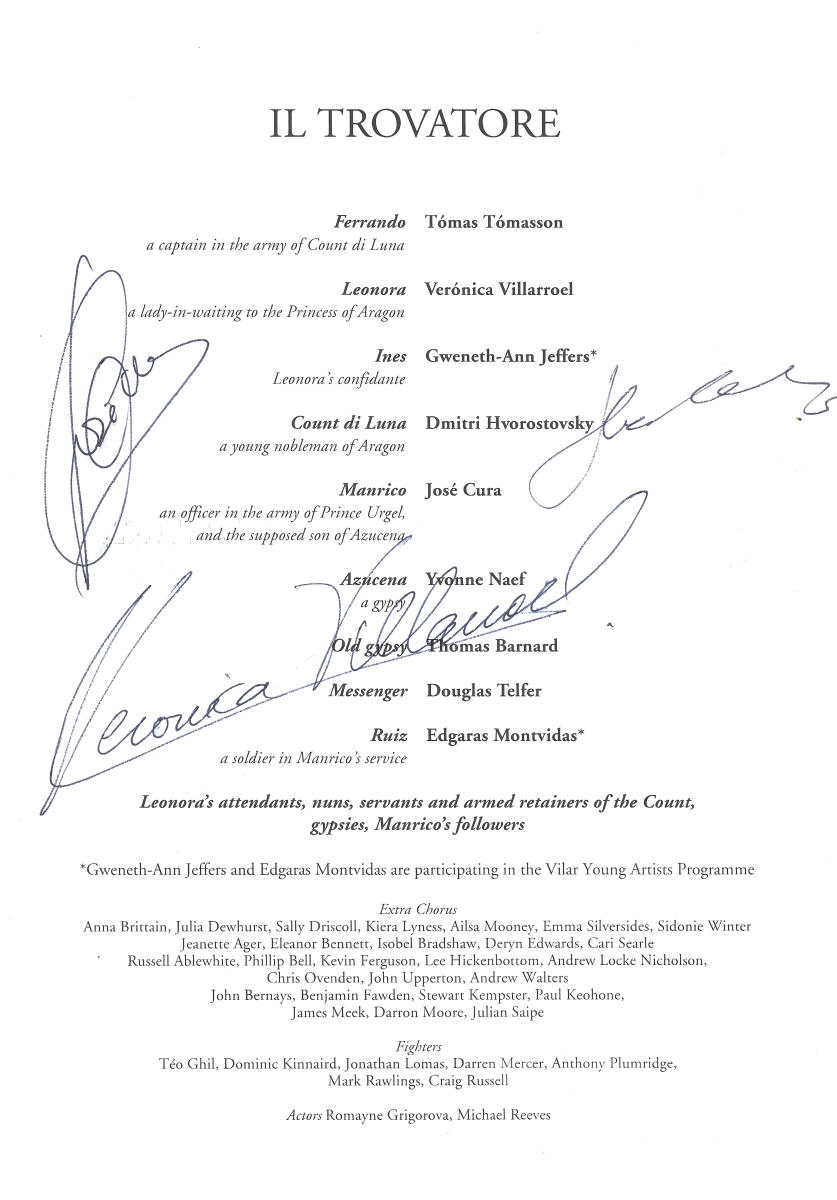

Il Trovatore

|

|

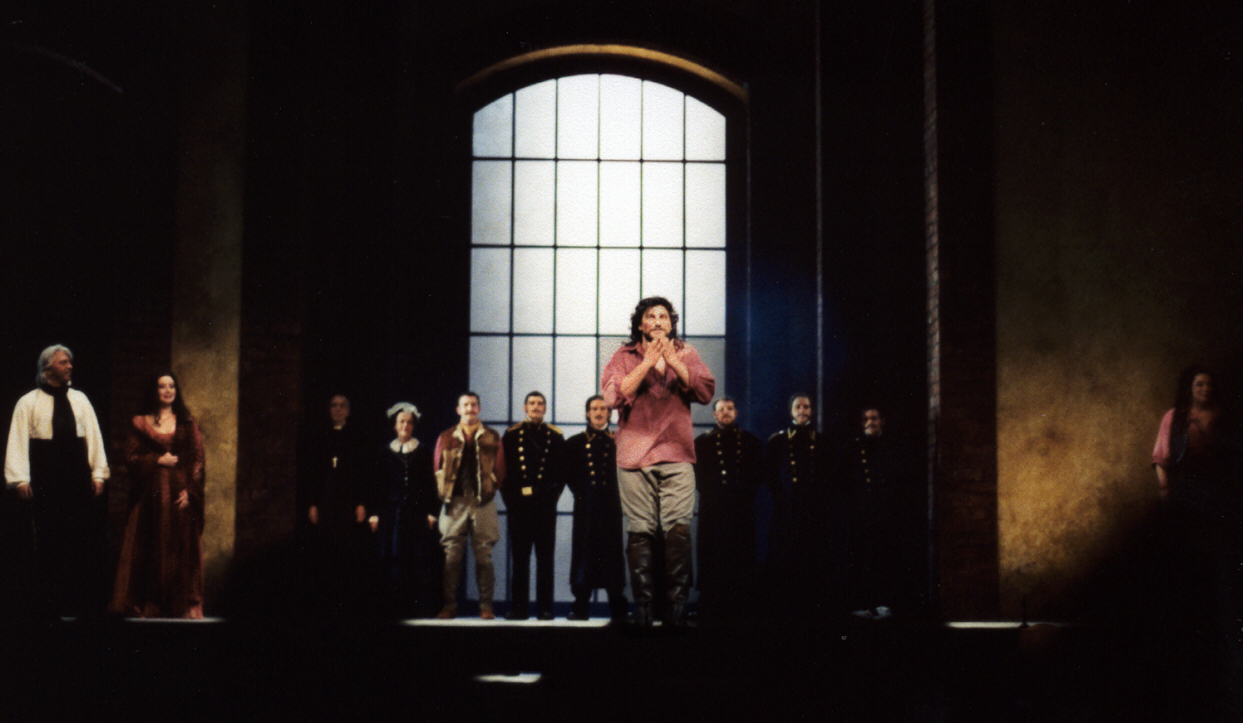

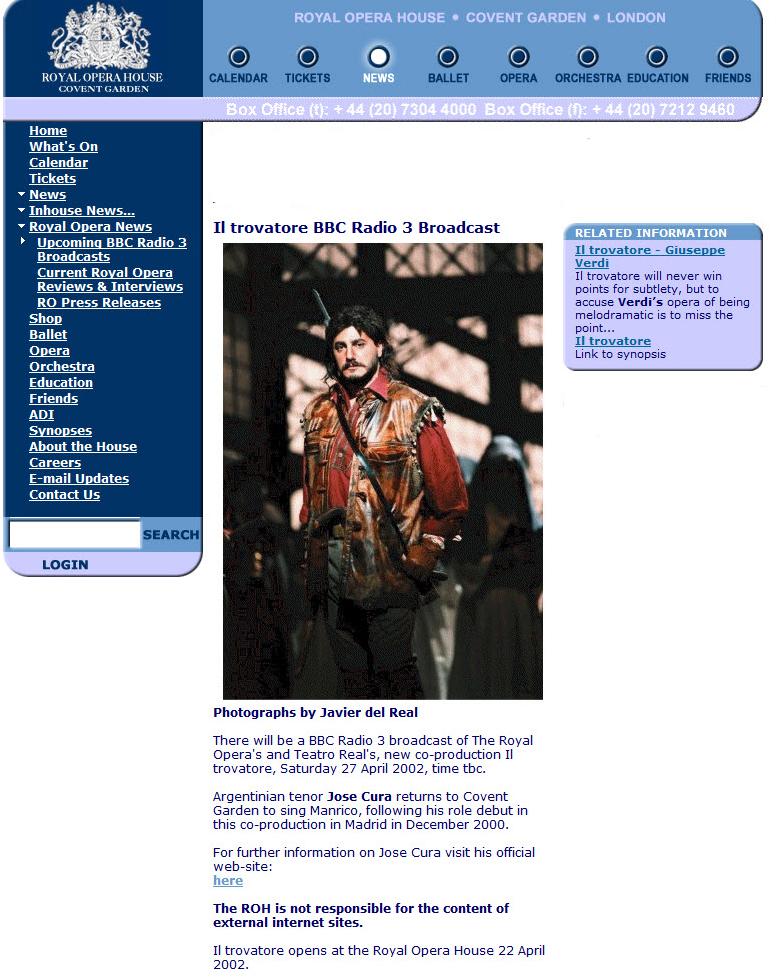

Madrid 2000

|

|

|

|

|

|

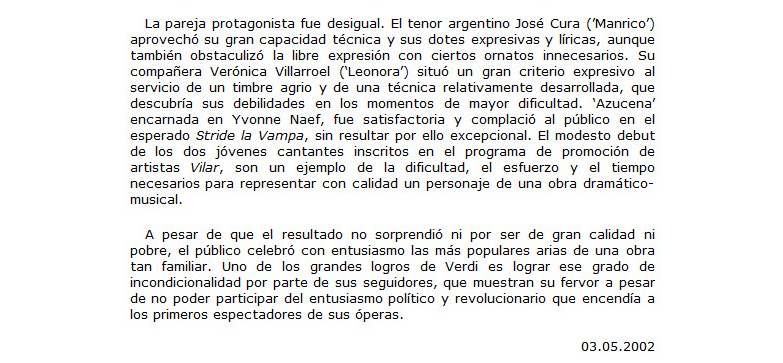

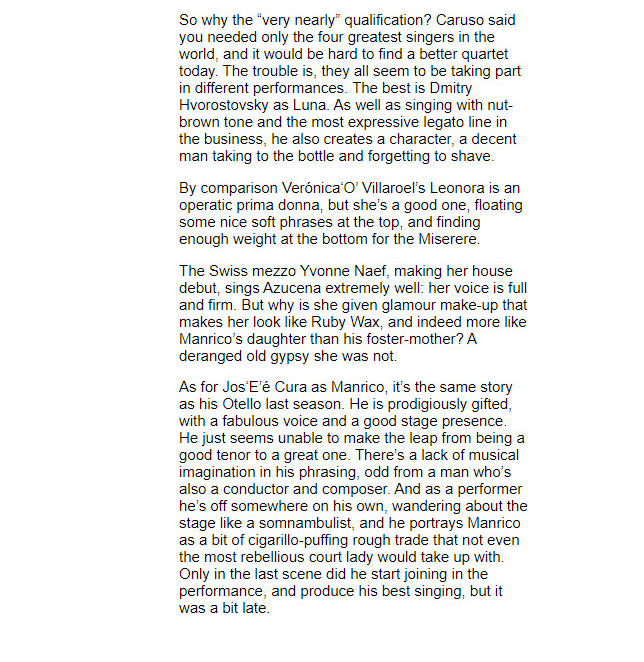

New York Times “IN the heart of Africa or the Indies, you will always hear Il Trovatore.” So said Verdi in a letter in 1862, nine years after the triumphant premiere of this swift-paced, melodically intoxicating Gothic chiller. Il Trovatore remained until roughly two generations ago the most beloved of his creations. Then it started losing ground. Only last week, Joseph Volpe, the general director of the Metropolitan Opera, volunteered: ''Il Trovatore isn't bread-and-butter like Bohème or Butterfly.'' Times change. Who among his predecessors would have agreed? Yet in this season of the centennial of Verdi's death, Il Trovatore is back with a vengeance. From Atlanta to Zurich, from Helsinki to Sydney, from London to Tokyo, the opera is everywhere. The Corriere della Sera, Italy's leading news daily, writes of 150 ''edizioni'' of Il Trovatore this season. Performances or productions? Uniform standards, please. Other sources list more performances but only some 30 productions. Whatever. These are numbers in the ballpark of Aida, Bohème and Carmen. New productions in Milan, New York and Madrid, unveiled within two days this month, have particular claims on the international public's attention. On Dec. 7, the feast of Ambrose, Milan's patron saint, the Teatro alla Scala opened its new season with a production designed and directed by Hugo De Ana. Dreamlike and monumental, choreographed beyond the point of mannerism, the show in the main delivered old-fashioned costume drama with fresh, contemporary flair. But the real news in Milan was the re-examination of the score (unplayed at La Scala for 22 years) by Riccardo Muti, La Scala's music director and supreme Verdian of the age, working from David Lawton's critical edition, published by the University of Chicago Press in 1992. To the noisy outrage of a few standees, the maestro vetoed inauthentic accretions (read: unwritten high notes) long honored in the name of suspect ''tradition.'' The papers, bursting with news of the opening, reported on little but a ''missing'' high C Verdi never wrote. Less conspicuously but more radically, Mr. Muti stripped off the verismo varnish applied by preceding generations, revealing an undreamed-of bel canto refinement. That same evening, the curtain rose on a new Met Trovatore chiefly noteworthy for the misbegotten production of Graham Vick, whose principal contribution was to transpose the action from 15th-century Spain to the Risorgimento, when Italian nationalists up and down the peninsula rose to shake off foreign rule. Elijah Moshinsky, whose staging had its premiere on Dec. 8 at the Teatro Real in Madrid, had the same bright idea, as if both directors were responding -- Mr. Vick in an abstract-expressionist manner, Mr. Moshinsky with a nod to the neo-Romantic cinema of Visconti -- to the same sophomoric homework assignment. But, of course, the concept was self-imposed. As Mr. Moshinsky told the Spanish press, the political clashes in the opera reflect those of Verdi's own day. In fact, politics are inconsequential to the action of Il Trovatore, and Mr. Moshinsky's sloppy take, like Mr. Vick's donnish one, self-destructed on arrival. In response to the jeers on opening night, the Met management eliminated some of Mr. Vick's most laughable excrescences. By the third performance, what remained between the new dead spots was still in the main mildly ludicrous, unpunctuated by the relief of a good guffaw. In Madrid the main interest lay not in the production but in the casting of the Argentine star tenor José Cura as the swashbuckling Manrico, the ''troubadour'' (or minstrel) of the opera's title. Mr. Cura blazed through the action in a red shirt, weapons aglitter, oozing charisma and injecting fierce sincerity into quick exchanges most singers throw away. Alas, Manrico's best scene was Mr. Cura's worst. ''Ah si, ben mio,'' that radiant love song on the eve of battle, streamed forth in an admirably seamless legato but in tones distressingly guided through the nose. Up in the gods, hecklers were waiting and let Mr. Cura have it, but moments later, it was his turn. From a smudged reading of ''Di quella pira'' (transposed down half a step, to finesse the ''traditional'' high C), he charged to the footlights, sword in hard, flung out his top note and actually flipped the gallery a bird. In the stadium, where more civilized standards prevail, there are penalties for such conduct. But the list of unprosecuted crimes against Il Trovatore is endless. Julian Budden, author of the magisterial three-volume ''The Operas of Verdi,'' reports that parodies began appearing in Italy and abroad within months of the opera's premiere. Omitting the murders, Gilbert and Sullivan had fun in ''H.M.S. Pinafore'' with their tale of an aristocrat and a commoner switched at birth. In ''A Night at the Opera,'' the Marx Brothers wrought their trademark havoc backstage and on during a performance of what just so happens to be Il Trovatore. For a lampoon that targets specifics, look up the Opera News of Feb. 18, 1967, in which the writer Nick Meglin and the artist Mort Drucker, both of Mad magazine, fill in what happens offstage between the scenes we know. But in the end satires of Il Trovatore only scratch the surface, leaving its mythic core untouched. Il Trovatore is to opera nothing less than what ''Oedipus Rex'' is to spoken drama: the revelation of the soul of tragedy in its purest form. In Il Trovatore as in ''Oedipus,'' ancient secrets unravel, devastating the innocent along with the guilty. But then, who is innocent? In the tragic no-man's land between reason and unreason, the great crime is to have been born. At that, a man may go to the grave never having known who he is. Such, nearly, is the fate of Oedipus, whose journey to self-knowledge has been likened to a detective story. Such, in fact, is the fate of Manrico, drawn by a power he cannot resist to an aristocratic world of arms and poetry. There he carves out his place as a knight among equals, keeping secret his identity as the son of a gypsy, Azucena. But he is not her son. The power that draws Manrico (as it draws Wagner's Parsifal, a knight's son whom his mother hopes to raise out of harm's way as a wild child of the forest) is in his blood. By birth, he is the second son of one Count di Luna, Garzia by name. Years before the rise of the curtain, a gypsy was discovered by his cradle, a grim sibyl reading his horoscope. (Alas, her predictions, unlike those of the oracle concerning Oedipus, go unrevealed.) Promptly, the boy fell into a fever, and the gypsy was burned as a witch. But a daughter, Azucena, lived to avenge her. She kidnapped the count's boy, took him to the place where the nobles burned her mother and threw him into the flames. The count's men found a little corpse smoldering on the pyre, yet the old man always clung to the conviction that the boy was not dead. Dying, he made his elder son, the young Count di Luna, promise never to stop looking. Such is the story the di Lunas' officer Ferrando tells his sleepy comrades in arms in the midnight scene that opens the opera. And as Azucena later lets slip in the hallucinatory account she gives Manrico of these same events, the old count was right: it was her own son she threw into the fire. ''Who am I?'' asks the horror-struck Manrico, and Azucena instantly recants. Yet she has told the truth. And the false Manrico is her intended angel of revenge. Conveniently, though this is none of Azucena's concern, civil wars are raging and the brothers are fighting on opposite sides. Worse, they are rivals for the love of the same woman, the queen's lady-in-waiting, Leonora. Leonora's devotion to Manrico, repeatedly questioned, never wavers -- except perhaps for one split second when he reveals, with patent shame, whose son he is (or thinks he is). Azucena has fallen into di Luna's clutches and been identified as the baby killer. In ''Di quella pira,'' the most rousing number in the opera, Manrico explicitly places his mother's life above his bride's anguish and charges off to battle, leaving the gasping Leonora in a state of mind too ambiguous to fathom. By the time the curtain rises again, her minstrel is languishing in prison. In the night by the prison tower, she strikes a bargain with di Luna: her person for Manrico's life. Then she swallows poison. In a fury, the cheated di Luna sends Manrico to the block, too fast for Azucena to stop him. With Manrico dead, she reveals her secret. Di Luna is shattered, and her mother's spirit has revenge. It has cost the blood of the real Manrico, burned in infancy, and of Garzia, whom Azucena raised and cherished as her own. Il Trovatore comes as close to perfection as any opera ever written: the quintessential fusion of action, word and music. Though Verdi and the poet Salvadore Cammarano did not always agree, both were by this time true masters. No one in the librettist's line of work surpassed Cammarano in reducing operatic action to its archetypal essentials. Likewise unsurpassed was his gift for compressing the sharpest emotions into brief, polished verses that bristle with memorable images. He was as attuned to motive as to mystery, and though he died suddenly, before crossing the last ''t'' and dotting the last ''i'' of this, his final libretto, he and Verdi had transformed a striking but unwieldy and clumsily dramatized source -- the Spanish melodrama ''El Trovador,'' by Antonio Garcia Gutirrez -- into a scenario that flies like an arrow. As for the music, to do it justice, a book might not suffice. Its rhythmic propulsion has often been remarked, no less manifest in the sawtooth contours of Ferrando's narrative than in Leonora's prancing dismissal of her confidante's prudent counsel. The way Azucena's gloomy song about the execution of her mother puffs into orchestral figures of pure flame when the vision returns is sorcery beyond the leitmotif manipulations of Wagner. The instrumental palette never ceases to amaze, with its exquisite winds, commanding brass and eloquent percussion (the opening drumrolls whirl through the house like thunder). But how much of the opera's spell survives at present in the opera house? At the Met and in Madrid, next to nothing. In the musical performance at La Scala, the lion's share.

|

|

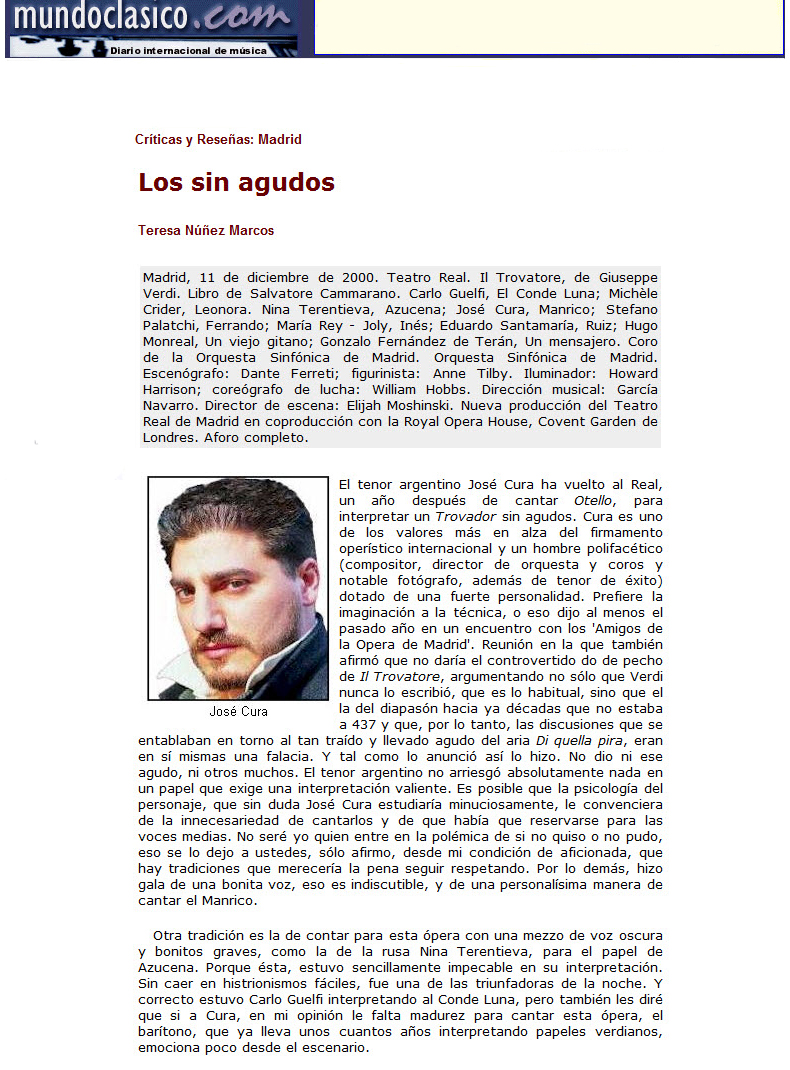

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.

The Glow of the Bonfire El Mundo Alvaro Del Amo 8 December 2000 [Excerpt] Author: Giuseppe Verdi / Musical director: García Navarro / Stage director: Elijah Moshinsky / Orchestra and choirs of the Madrid Symphony Cast: Carlo Guelfi, Michele Crider, Nina Terentieva, José Cura New production of the Theater Real in co-production with London's Covent Garden MADRID.- Rarely has the opera form treated a subject with such enthusiasm and forcefulness. A matter of extreme gravity, the only important one, the most likely to interest everyone: death. A handful of creatures, overwhelmed by ancient misfortunes, pretend to love and pretend to take revenge, but what really motivates them, as we would say today, is the practical exercise of killing and dying, killing, killing oneself, seeking one's death so that it may have a deadly effect on one's brother. [...] These creatures of tragedy hide their secrets. Manrico is the characteristic impetuous and brash Verdian tenor, with little time for melancholy. José Cura faced the role with a desire for freshness and a dedicated purpose to communicate verve and nuance. Such intentions were glimpsed only intermittently in a still developing performance, with severe ups and downs. Leonora is the prototypical soprano, prone to go to convents and ingest poison. Michele Crider showed great care and dedication but said little about her character. Count Luna also repeats the figure of the baritone established by the composer, a well-placed gentleman who refuses to abandon his impossible love. Carlo Guelfi lacked empathy and conviction, ease and mastery. Azucena is the most lucid and truculent mezzo role described by the musician. Nina Terentieva’s voice was not always impeccable and controlled, but she skillfully identified with her role, the only one of the main quartet within a healthy Verdian tradition. The orchestra and the conductor, after a frosty and faltering start, were infected with the vibrations of the black drama. The audience showed variety in its demands, translating into protests manifested in the balcony but countered by warm response in the stalls. García Navarro was scolded but the most deafening, unanimous, and, it should be said, deserved, booing was reserved for Mr. Moshinsky.

|

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive. Controversy El Pais December 2000 [Excerpt] Il trovatore, the forbidden fruit, the swan song of bel canto, the opera of which Arturo Toscanini assured that it was necessary to gather the best singers in the world to mount, tempted La Scala in Milan, the Metropolitan in New York and the Teatro Real in Madrid in the run-up to the Verdi Year. The division of opinions has jumped, passionately, at least at the European level: Riccardo Muti and Luis Antonio García Navarro were aware of where they were getting into. Muti, at a conference at the University of Milan, stated that "Il trovatore is the quintessential opera, Giuseppe Verdi's most performed opera," and García Navarro, in an interview published in this newspaper the day before yesterday, stated that "it is the opera that demands the greatest vocal effort of all those written by Verdi, and perhaps in history.” In any case, both of them went ahead with all the consequences for this cursed opera which, by its own division into four parts of eight scenes, is closer, so to speak, to the serialized novel than to the theatrical structure conventional and, in the Spanish case, it enters into direct analogy with a bullfight of eight bulls. Twenty-two years had passed since La Scala had programmed this title. Muti focused the foreseeable controversy on the devilish high note in the pyre aria. He defended philology against tradition. "It is not written in the score," he said, to which the supporters of the inclusion of the note replied that Verdi was not averse to it while he was alive, though no written evidence of this has been found. Salvatore Licitra, the tenor who assumed the fateful character of Manrico, did not sing the ‘C’ and the loggionisti, who had seen their survival in serious danger in recent months and whose presence is currently limited to 139 seats, protested against the tenor and against Muti […] who, at one point, intervened to ask that "the celebration of the Verdi Year not become a circus." In the final bows, neither the singers nor Muti appeared alone, but always in groups. And in Madrid? Well, the controversy was also present, although not focused solely on the C; the first isolated whistles appeared in the second scene and acquired greatest intensity in the aria Ah sì, ben mio, coll'essere before the famous pyre cabaletta. There was also an exchange of impressions among the audience and severe protests against tenor José Cura, a singer whose personality fills the stage and in the end responded to the heated division of opinions by saluting in a bullfighting manner. Cura's singing did not have a clean execution, but was rather precipitous and confused. […] Stage director E. Moshinsky and set designer Dante Ferretti brought the action, which in the libretto takes place in the 15th century between Aragon and Biscay, to the years when the score was written, the time of the Italian Risorgimento. The first half of the production is more creative and powerful scenographically than the second, despite some gratuitousness. Overall, the effort was rather poorly received by a considerable sector of the audience. Another division of opinions reached García Navarro’s work. His conducting was very neat, especially in the third, fourth and eighth scenes. Attentive to the sonic detail, to the almost chamber-like conception that worked to the benefit of the voices but led to a lessened sense of dramatic tension and the wild atmosphere. It was, in any case, a coherent reading, although at times a little dull, to which the Madrid Symphony responded with precision. In Milan and Madrid no one was bored. Not one cough, not one sigh. Verdi continues to stir passions. The opera is still alive.

|

|

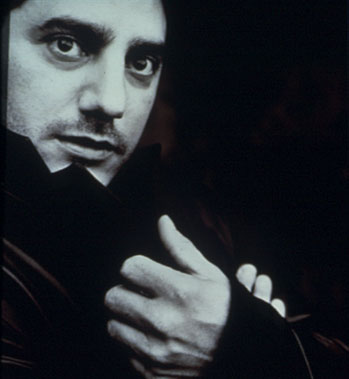

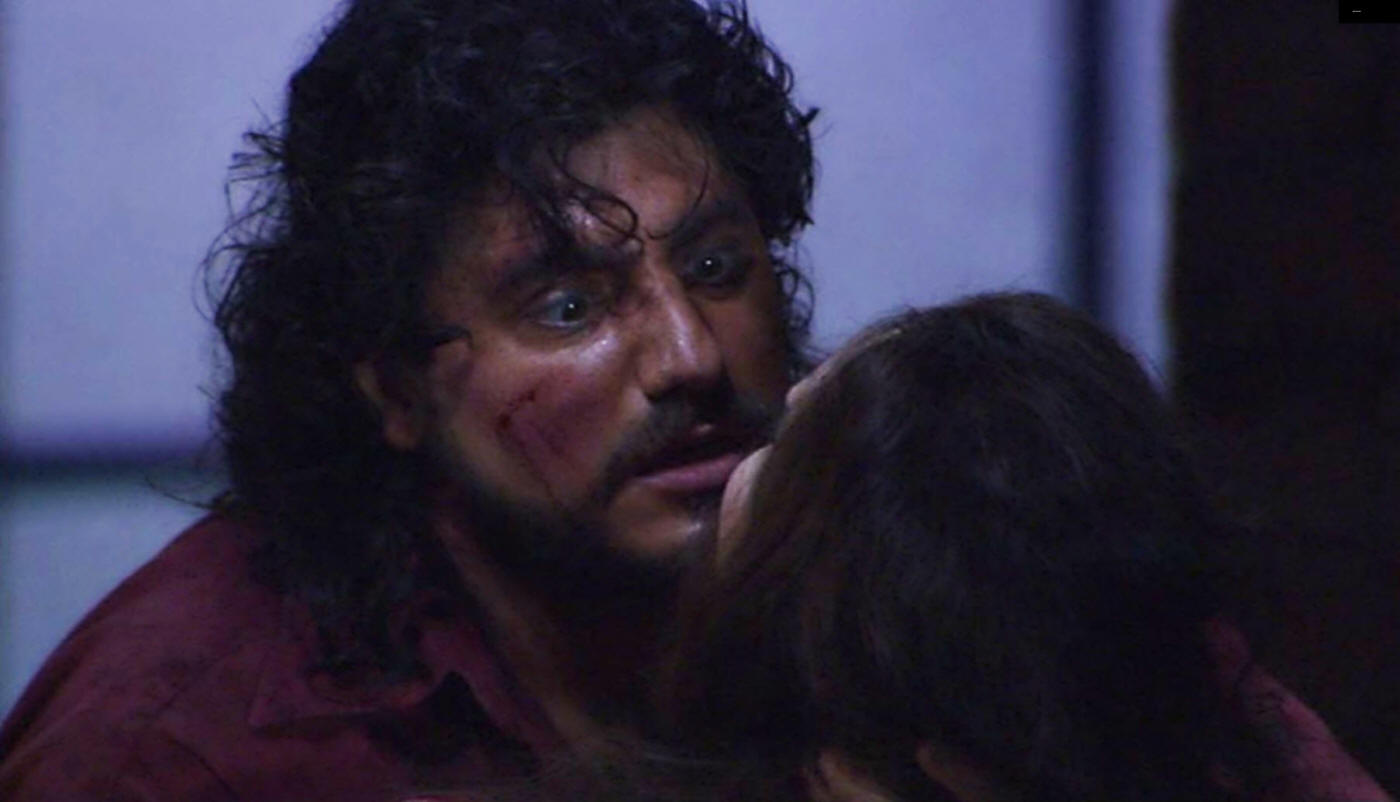

Il Trovatore, 2000, Madrid: One of the main attractions was José Cura, who played the troubadour Manrico. Cura was always in the role. His singing was beyond reproach, but the emotion inherent in the role was restrained. His role has its strong point in the dramatic attack and it was in the transmission of this characteristic that the tenor failed to connect with an audience that expected more from the Argentinean. Estrella Digital, December 2000, Juan Pelegrín

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

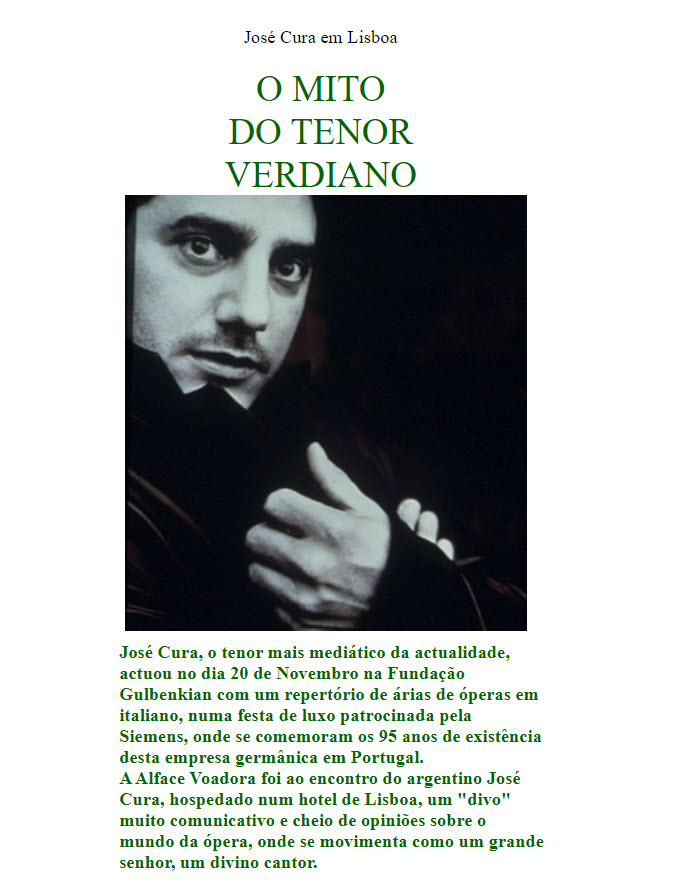

Note: This is a machine-based translation. José Cura uses language with precision and purpose; the computer does not. We offer it only a a general guide to the conversation and the ideas exchanged but the following should not be considered definitive.

José Cura: "I am not arrogant" La Capital 9 January 2001

[Excerpt] The Rosario tenor confessed his weariness to Escenario a fortnight after the Madrid scandal broke “I wish the whistles had been against me!” says tenor José Cura to Escenario from his house in Madrid two weeks after the scandal of the Teatro Real in Madrid, when the singer reacted to the whistles and protests of a sector of the audience during the performance of Giuseppe Verdi’s opera, Il Trovatore. Quick to react, the singer immediately declared that the protests and whistles were prepared to have the widest possible coverage in the press. The fifteen days away from the event has not appeased Cura: “If the whistles had been only against me, it would all have been an amusing, gossipy anecdote, one more of many that populate the history books of opera. Unfortunately, it is not that simple. Since the current artistic and musical director of Il Trovatore, (Luis) García Navarro, began his administration, a campaign, crudely orchestrated, has tried to make him resign due to exhaustion. His tenacious and courageous fight against these low machinations has cost him more than one problem, including his health. Systematically, every artist of a certain prestige who sings at the Real after an invitation by García Navarro is booed. Among others, and to name people Argentines know, the Italian bass Carlos Colombara and the Chilean soprano Verónica Villarroel. Veronica, after a performance of Turandot in which she was especially humiliated by this little group, addressed them from the stage to invite them to come to her dressing room to discuss. She's still waiting for them,” says the unforgiving Cura. The 38-year-old tenor, who has international commitments through 2006, adds that in recent days, “García Navarro, whom I have known for many years, made some comments in the press, thanking me for being available to the Teatro Real, seeing that I turned down other things so I could sing in the theater of the city where I live. I wish I’d never done that! In the past, other artists went through the same here. Only this time, because I am who I am, the media coverage was enormous. Cura pauses and then affirms: “It doesn’t matter, Rosario knows me well. I am not as arrogant as some want to make people believe to justify my attacks, or defenses, against certain types of nonsense. Rather, I am a dreamy Don Quixote. I am a dreamer of a world without mediocrities and cowards, of a world where my neighbors, whether they call themselves friend, neighbor or colleague, rejoice in the triumphs of their fellow men instead of spending their lives looking for the weak spot where they can attack and demolish, thus alleviating their own frustration.” LC: Did this series of actions and reactions harm you or, on the contrary, did it give you more space in the press than you would have obtained had you not mediated these offensive acts? José Cura: Unfortunately, people are rarely talked about someone when it is not due to some scandal. In 1999, after my debut at the New York Metropolitan, there was everything, good and bad, as always. But some newspapers in Argentina limited themselves to translating only what was bad. A little later, this man from Rosario made the cover of no less than the New York Times entertainment section, with the not insignificant title of: José Cura only Sacred Monster of the new generation of singers. Did any of you hear this at home? How many media outlets have translated this for my people? LC: You have written an open letter ... José Cura: I just tried to put some things in their right place. For example, for the opportunistic Mr. So-and-So to say that I am a bluff, a lie, an invention, is still a compliment...to the inventor, of course. On the contrary, the insult is received by the public who, according to them, are so deaf, blind, and ignorant that they do not realize the deception. And not just the public: theaters around the world - who are not fortunate enough to have these scholars open their eyes - are making the mistake of falling into the same trap. Useless to try to conceal the facts by dismissing them with a simple: the Divo Cura cannot bear to have his limits marked! O something like that. Too comfortable. Too easy. Unfortunately, this fragile Kafkaesque strategy succumbs to devastating evidence: the list of top singers who have passed through Teatro Real, and who no longer want to return because they have been unfairly mistreated, is getting longer and longer. LC: Do you think that these events will affect your artistic future? José Cura: Yes, but not in the professional sense but in the personal one: sometimes I ask myself why I can't be an anonymous artist, like so many others (most of them)? LC: Why didn't you celebrate 2001 in Rosario? José Cura: On December 26 I sang the last performance of Il Trovatore and on the 27th I was already rehearsing in Zurich. LC: Are you still thinking about singing again in your hometown? José Cura: It's not up to me. I wish it was! LC: One week after the scandal, what image will the Argentinean public have of you? José Cura: I don’t know. Knowing the facts and the truths that motivated them, each one will take the position he wants or can: the public, what his conscience dictates, the media, what the editorial staff dictates. I only ask for objectivity. LC: Is the degree of public exposure that artists of different genres justified? José Cura: It depends on the cases. If you are an invention, yes, it is justified. If not, what’s the purpose of the invention? In my case, many times I wonder if it is not all this publicity, all this apparatus, this industry that is mounted on my back, which makes dissidents suspicious. It’s just that today, when we are being sold tofu as roquefort, everything is suspicious. I've spent more than half of my life preparing for this and I'm not happy to be on the list with late-night improvisers. LC: Do you feel alone in these difficult times? José Cura: No. If I did, I would have left everything long ago. LC: Do you feel that your country supports you in any way? José Cura: As always, there is everything. In the case of the Real, for example, there were media outlets that limited themselves to publishing what the agencies sent them, without bothering to find out the truth. Others, like La Capital, La Nación, or Clarín, called me right away. LC: What are your expectations for 2001? José Cura: See how my wife becomes more and more beautiful and watch my children grow.

|

|

Il Trovatore at Teatro Real

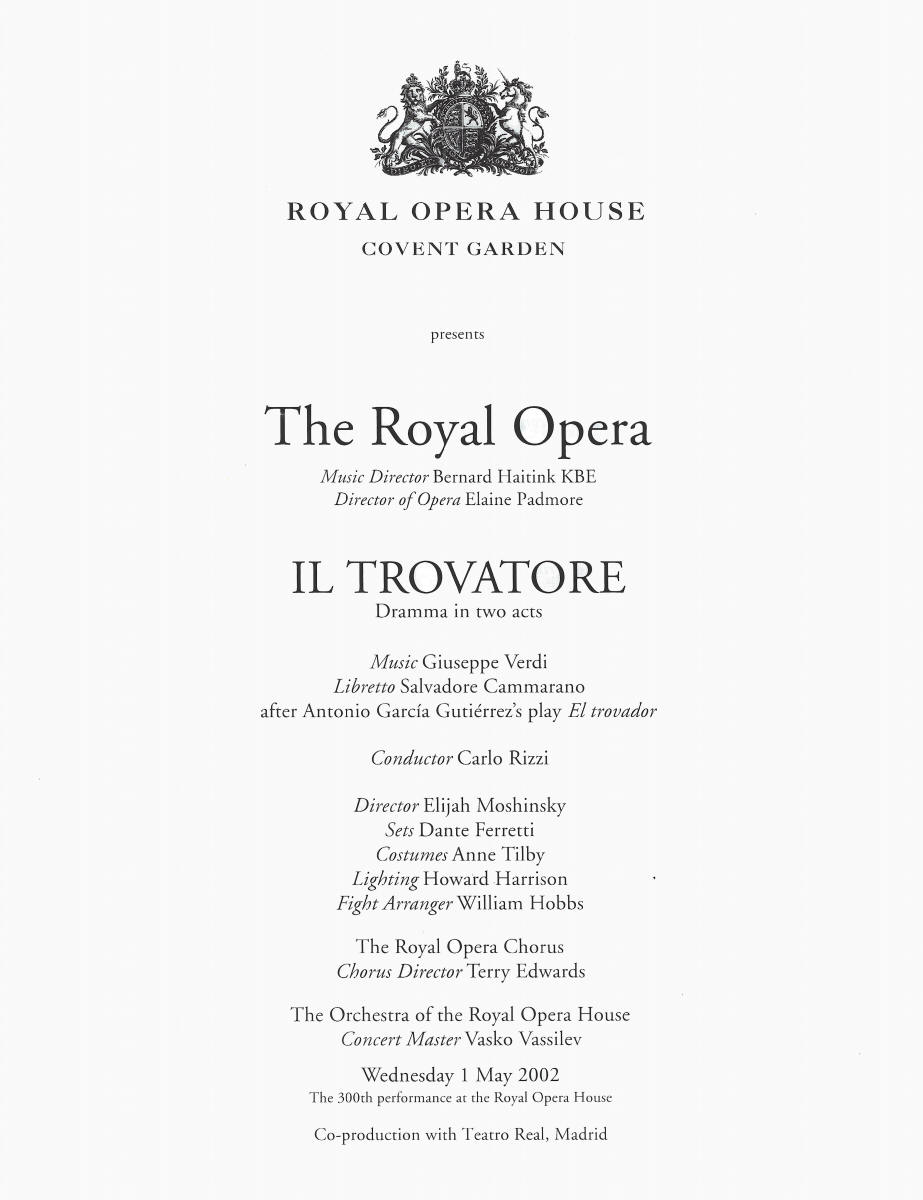

Sometimes magic happens.

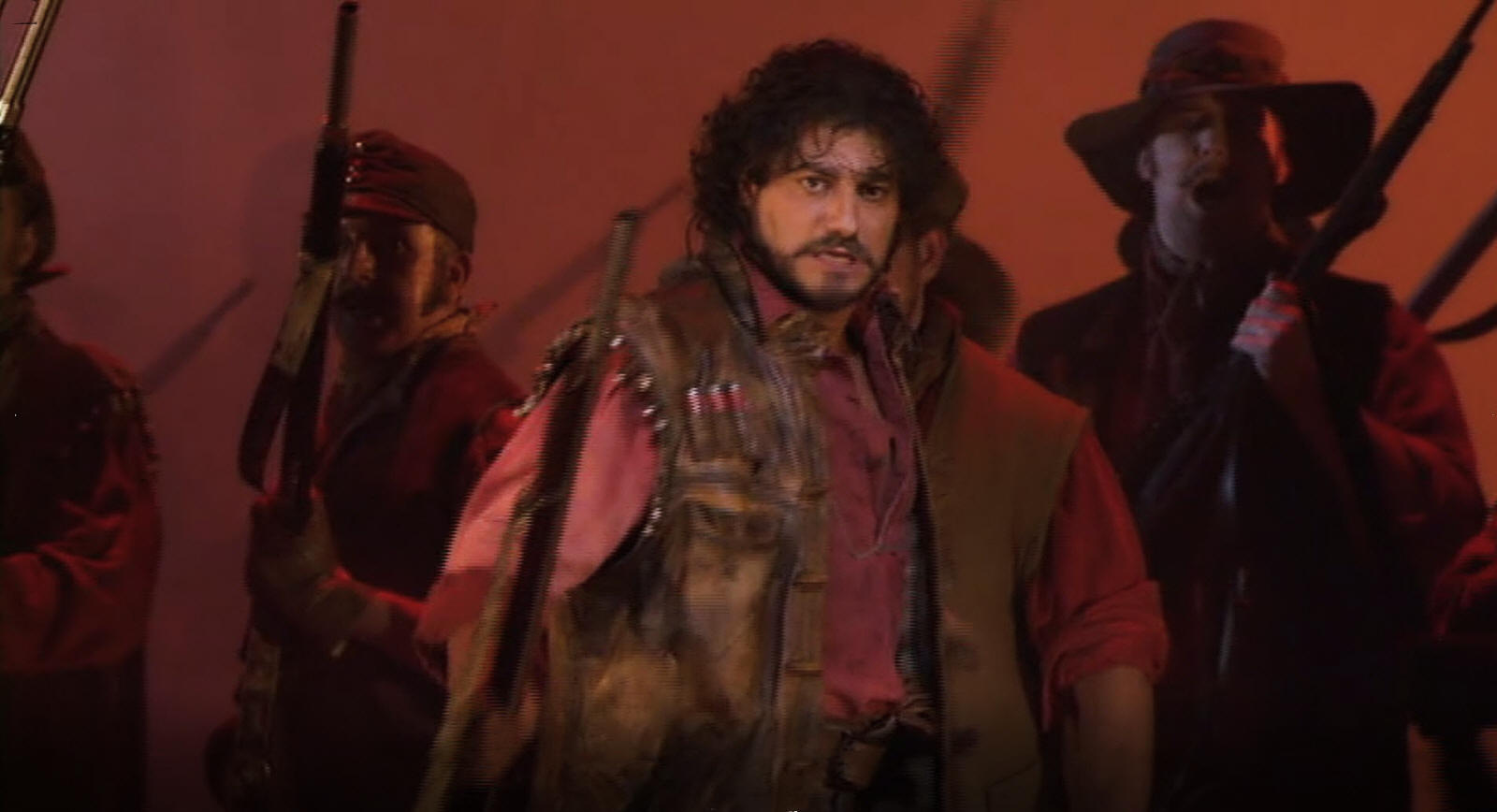

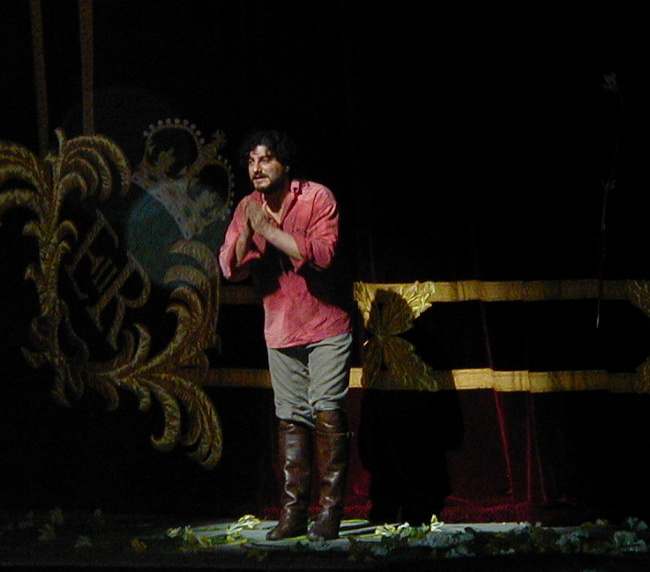

One night in late December, in a dark theater in Madrid, Spain, Jose Cura walked on stage as Manrico in the opera Il Trovatore. At that moment, magic happened.

All the actors (Michele Crider as Leonora, Carlo Guelfi as Count de Luna, and Nina Terentieva as Azucena) put great effort into their roles, but the evening belonged to Mr. Cura. Once he appeared, the atmosphere in the beautiful Teatro Real changed. Everything became electric. Everything became magical.

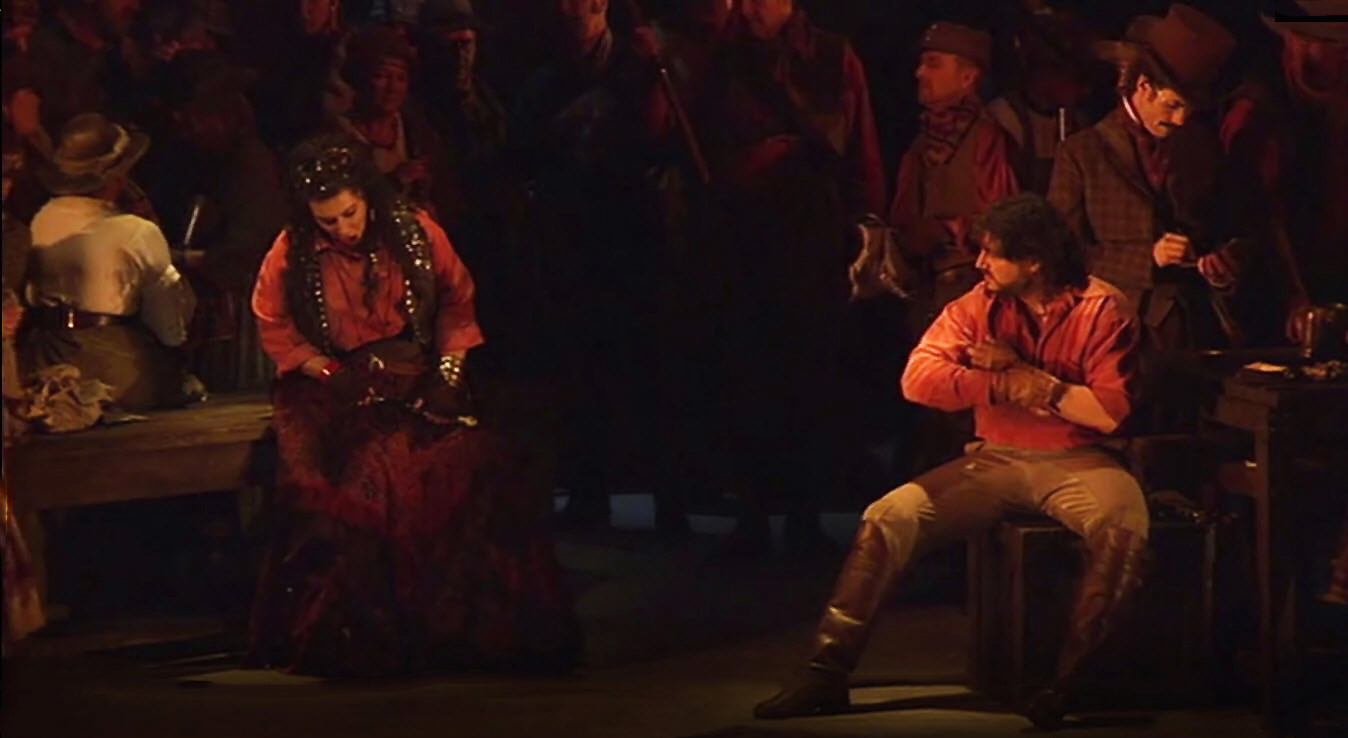

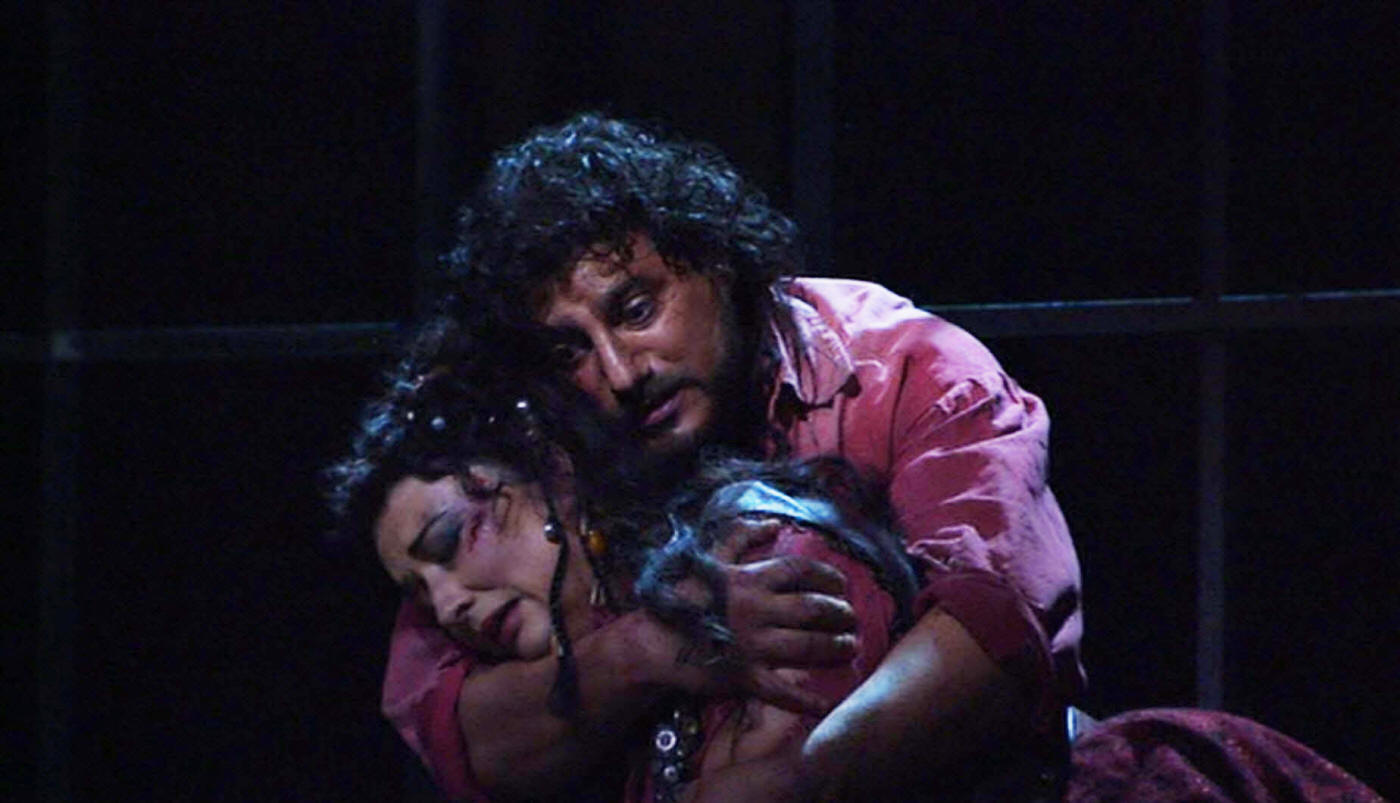

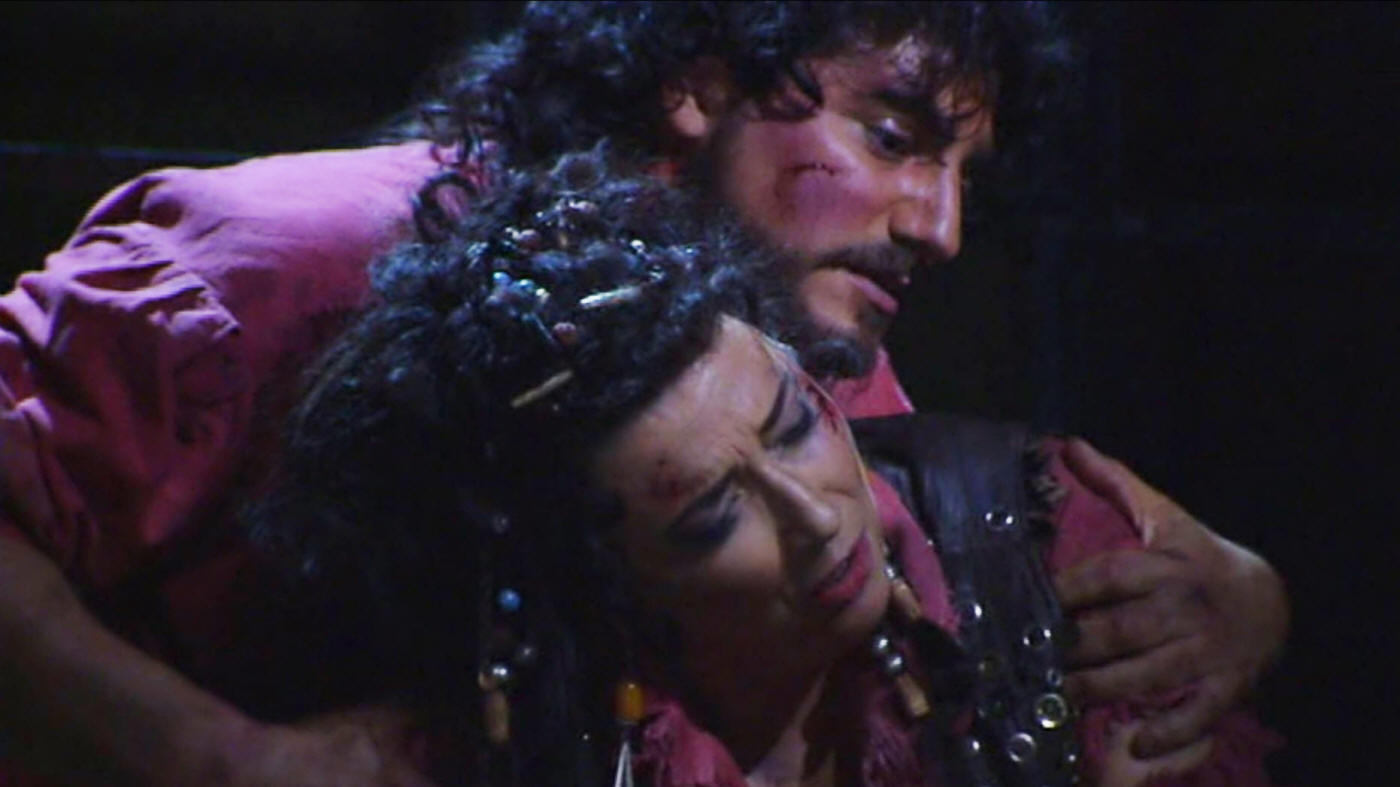

With long hair and short beard, knee-high boots, tan pants, pinkish-red shirt and leather vest, Mr. Cura looked the part of the romantic lead character, the troubadour. Stepping between Leonora and Count de Luna after singing a passionate love song off-stage, Mr. Cura’s Manrico was warmly attentive to his love, boldly defiant to his enemy. In his duel with the Count, Manrico moved so easily across the floor and used his sword so effortlessly that it was clear he was much more than the simple son of the gypsy woman, Azucena.

Mr. Cura played his poet-warrior as an honorable man with a big heart. In the second act, though he had no love for his enemy, Manrico stopped his men from killing their prisoners. He recounted in wonder how fate kept him from killing Count de Luna after beating him in a duel. His face and voice sifted through a hundred emotions as Azucena told the story of her mother’s death at the stake. His confusion about his identity after the gypsy confessed she threw her child into the flames was softened by his affection for the old woman. In the end, Mr. Cura created a complicated character whose loyalty, sense of honor, and kind heart made it impossible for him to believe he was anyone other than Azucena’s son.

He was also very brave. After Azucena is captured by de Luna and sentenced to die at the stake, Manrico leaves Leonora and the safety of his castle to rescue her. In one of the most unforgettable moments in a night full of unforgettable moments, Manrico the warrior gathered his weapons, called his men, and sang ‘Di quella pira’ with such passion my toes tingled. It was magical.

|

| The final act was awesome. Locked in prison and waiting to die, Mr. Cura lets Manrico’s heart shine through his singing. Seeing that his mother is distraught, Manrico consoles her. He joins her in a haunting song about their beloved mountains, blanketing the crazed woman in warm memories. Comforting her as a father comforts a frightened child, he is finally able to calm her enough that she can sleep.

Mr. Cura makes the innocent devotion of Manrico toward the woman who will cause his death heartbreaking. Manrico doesn’t know the reason why his mother is upset.. He doesn’t understand Azucena is struggling against the need to sacrifice the man she has come to love as a son. He doesn’t realize it is her plotting that will destroy everyone. He acts only as a loving son acts when concerned about his mother. This generosity of spirit marks Manrico as a great man and makes his death even more tragic.

The conclusion comes quickly. Leonora dies proclaiming her love for Manrico. Count de Luna flies into a jealous rage at the final victory of his enemy and goes back on his promise to free Manrico. Refusing to hear Azucena as she begs him to listen to her, he orders Manrico’s immediate execution.

Mr. Cura’s Manrico is noble even in death. Calling a last, loving farewell to his mother, Manrico faces death courageously. He is stabbed; then his throat is cut. As his legs give out and he begins to fall to the ground, Azucena screams the truth. In horror, Count de Luna rushes to his once hated rival, catching his brother as if he can somehow undo what he has done. Azucena, torn between joy at keeping her promise and horror at watching her son die, is consumed by her madness.

I applauded until my hands hurt and still applauded more.

Afterwards, I went backstage to tell Mr. Cura how much I loved his performance. It was very crowded and very noisy and very exciting—but also very overwhelming and maybe even a little dangerous for a tiny girl who is only elbow high on most people. But getting to see Mr. Cura is worth risking a black eye or bumps on the noggin, so I waited while the grown-ups chatted and Mr. Cura signed autographs and smiled for pictures.

It was a long time before I could get close enough to say anything to him. By then, even though Mr. Cura welcomed me with a big grin and open arms, he looked so tired! After all his hard work to create a special evening for us, I realized the best gift I could give him back was a quick hug and a whispered ‘thank you.’

But what I really wanted to do was tell him about the magic I felt in that dark theater on that cold, rainy December night.

And thank him for being the magician.

Kira

|

|

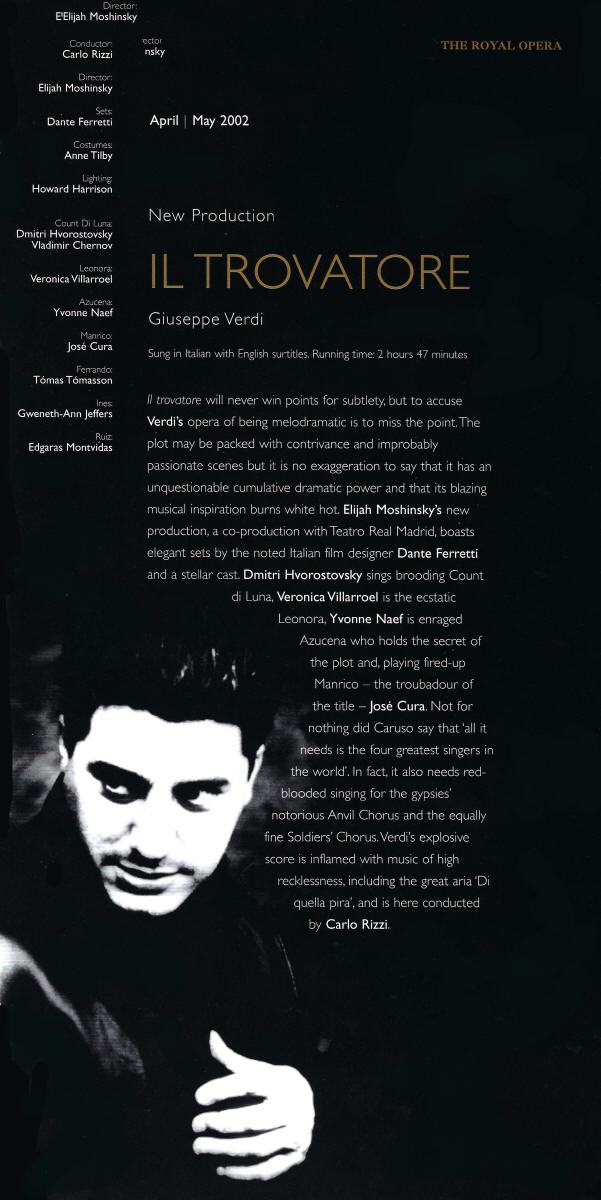

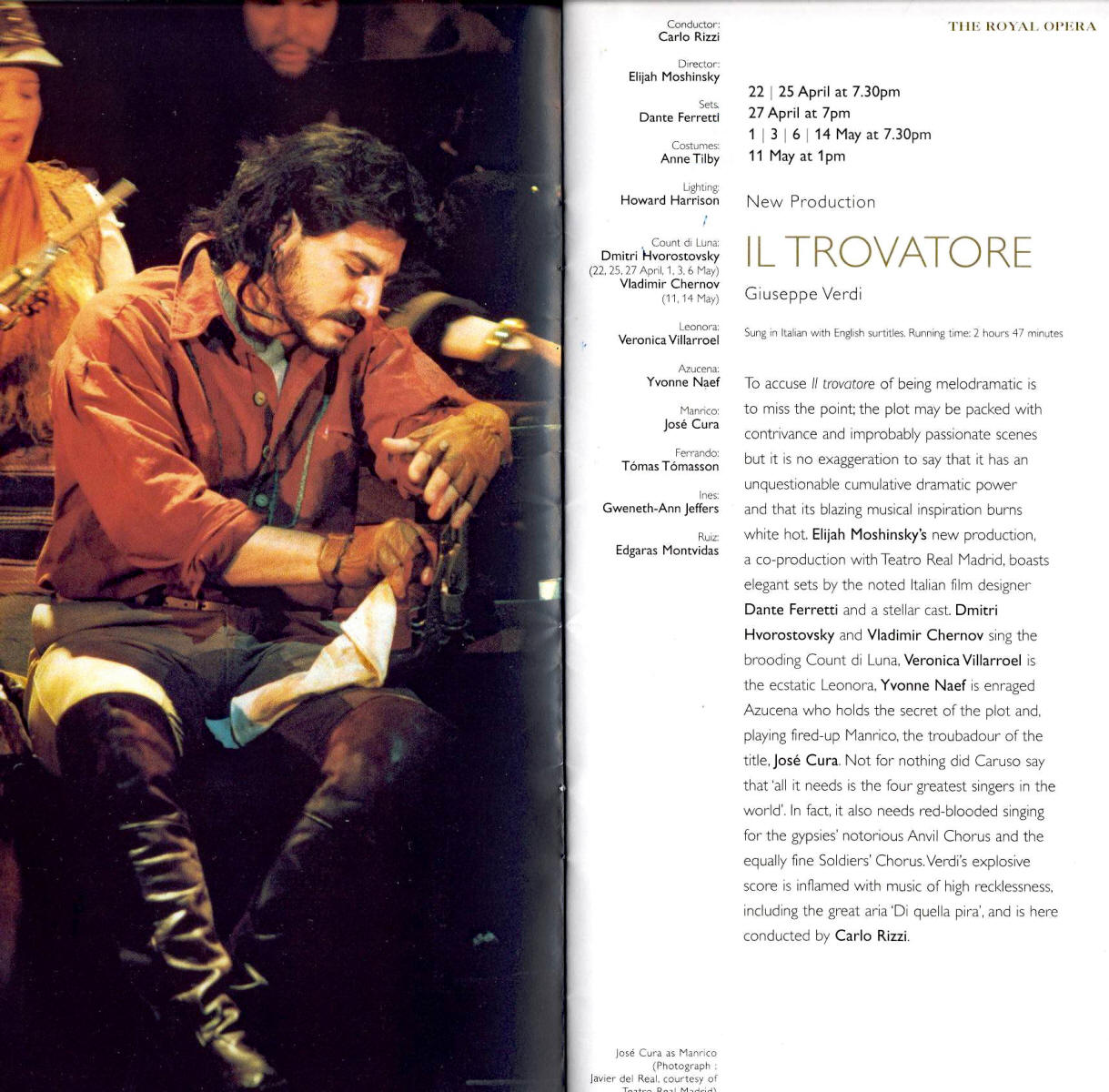

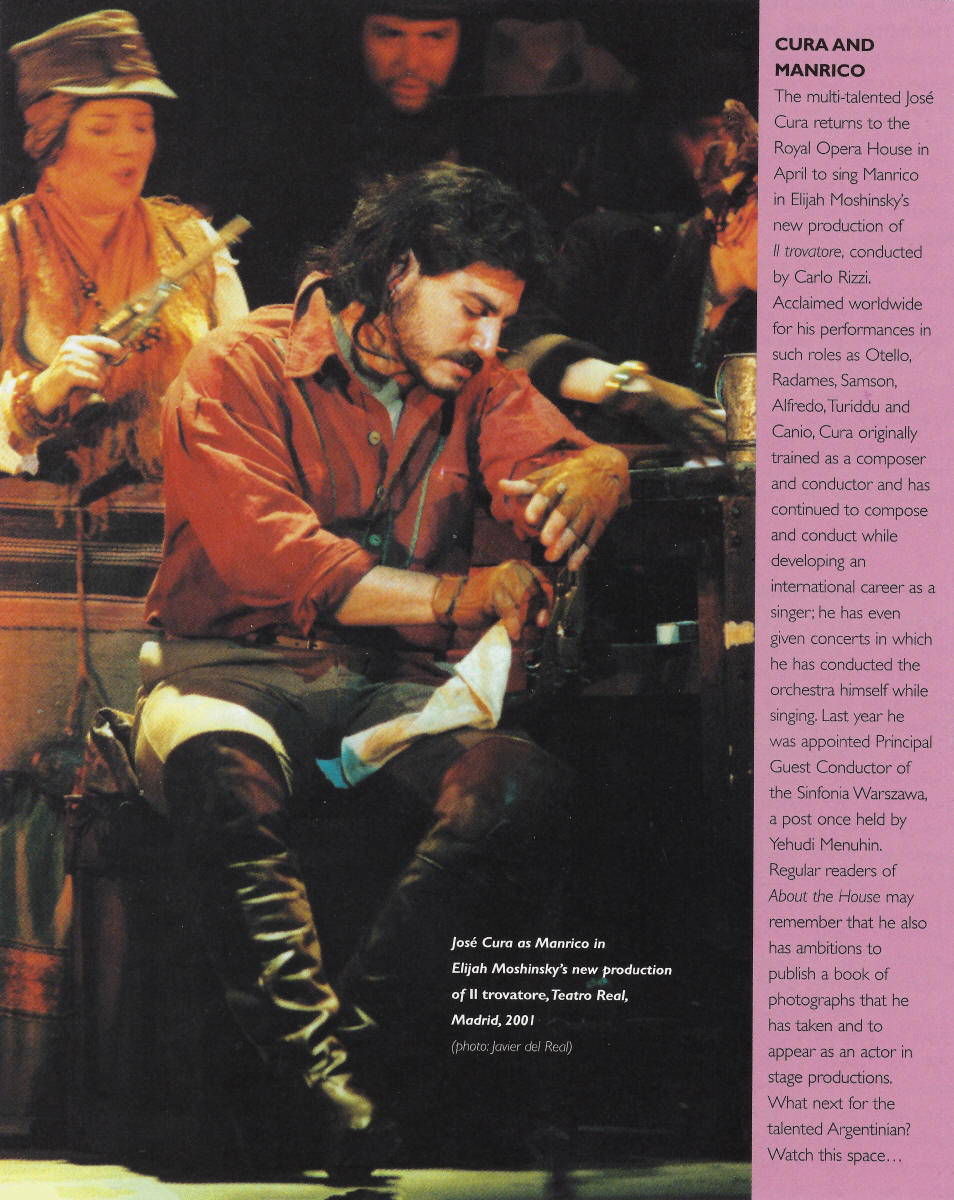

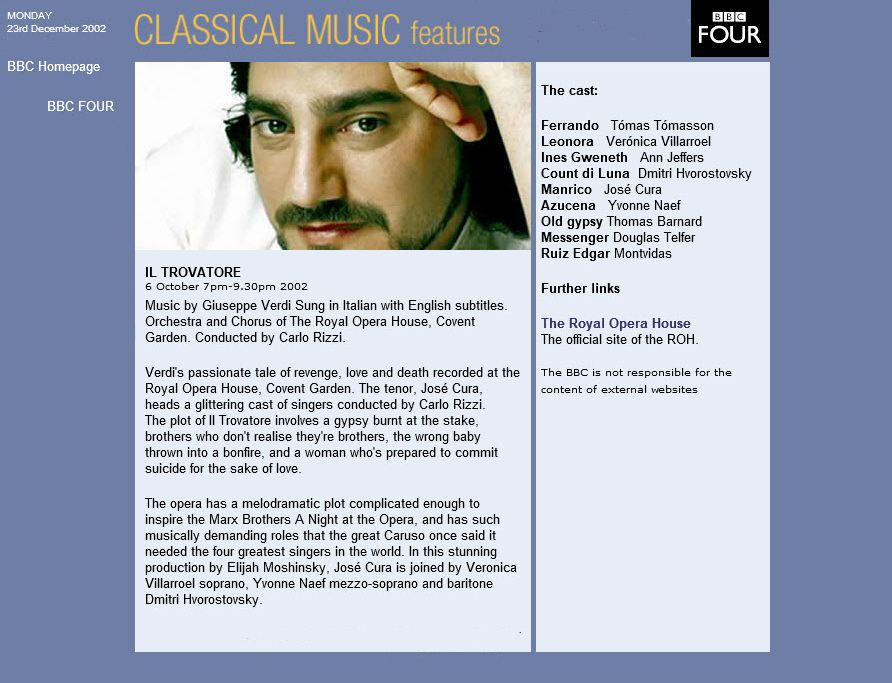

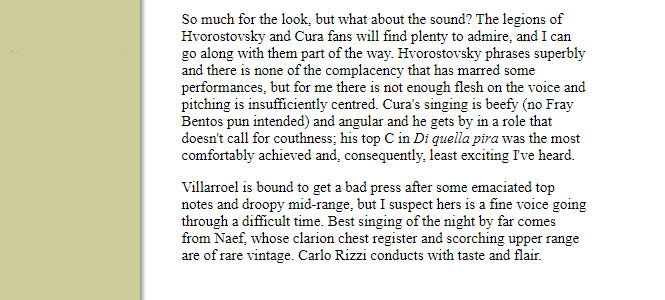

Royal Opera House 2002

|

|

|

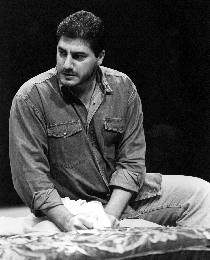

Trouble on

the high Cs Telegraph Michael White 18 April 2002 The 'fourth

tenor' José Cura will shout back if you boo

his singing. Michael White finds there is more to

opera's Latin lover than sex and ego WHETHER or not José Cura is the Fourth Tenor, the Sexiest Tenor or the Most Arrogant Tenor - and he's had to deal with all those propositions at one time or another - he is certainly the Tenor who Talks: the one who speaks his mind and damns the consequences. Which may well explain the slight suggestion of anxiety in the Royal Opera's preparations for Il Trovatore (strictly no press at rehearsals) opening next week with Cura in the lead role of Manrico. When the show - which is new to London but not to the world - first played in Madrid a year or so ago, it was booed. With vigour. But instead of biting his lip as singers are supposed to in such circumstances, Cura hit back with a lecture from the stage. "I'm here to sing for people who love opera," he proclaimed, "not people whose behaviour stinks." Result: a minor riot. Sitting down with him last week I couldn't help asking if he had prepared a few words for the Covent Garden audience - should the need arise. "Please God it won't. Madrid is a special situation, with a small group of people who boo everything. It's pathetic. So I had to say something: why not? And you know, when I spoke, 90 per cent of the audience applauded. The other 10 per cent? They continued to boo. Too bad." One of the criticisms of the 10 per cent - and to be fair, they did indeed boo everything about the show - was that Cura faked some top notes which, in Trovatore, are an issue. There are lots, and people count. By designation Cura has the voice for them: he's a "dramatic" tenor in a line of succession that stretches from stars of the past such as Mario del Monaco to the Pavarottis and Domingos of our own day. But the voice is slightly darker, slightly heavier than many tenors of his type and age (39), which is why he already sings the role of Otello that tends to get left until later. A voice geared down to sing Otello doesn't easily gear up to high Cs. So how, I wonder, is he managing? "I don't approach the Cs with nonchalance - they're not my everyday thing - but they're possible. Why not? I've never been too concerned with these labels - dramatic tenor, whatever - that limit what you're supposed to sing. I don't like to feel confined." More broadly, though, he does confine himself to Italian repertory. Apart from the odd booking for Bizet or Saint-Saens, he sticks to Verdi, Puccini and lesser verismo composers such as Giordano and Mascagni. Strong, emotional, straight-to-the-heart scores. Nothing cerebral like Wagner. "That's because I don't speak German and avoid singing in languages I haven't mastered. I don't sing in English either, although one day I hope I have the courage for Peter Grimes: a fantastic piece but, my God, terrifying. I look at the score and I piss my pants it's so hard. "But who says Italian music isn't cerebral? That's only how it gets interpreted. If you're a second-rate musician you're OK with Mascagni because he helps you so much you can get by on banality. Wagner doesn't let you be banal. This doesn't make Mascagni bad. Just the performance." Cura's defence of his repertoire is all you would expect from the Tenor who Talks. In a profession where success or failure hangs more on the dimension of the lungs than of the brain, he stands out as an articulate, intelligent, all-round musician. At university he studied composition and conducting, and he's recently been made Principal Guest Conductor of the Sinfonia Varsovia, the Polish orchestra that used to appear under Yehudi Menuhin. He may not be, as yet, the greatest maestro; but there are some very famous tenors who can barely read a score. The paradox of Cura's fame, though, is that to a large degree it rests on sex and ego. From the time he came to international attention he's been typecast as the Latin lover of the opera world - to the apparent joy of women's magazines but not of critics, who were quick to welcome him as a potential Tenor No 4 but similarly quick to damn his stage performances as posturing and arrogant. When he started to appear in concerts singing and conducting at the same time (an ungainly novelty for which he stood, back to the orchestra, and flapped his arms together like a duck in take-off) it did nothing for his credibility. The memory still hurts. "If there's one thing I don't do it's posturing, and London is the only place on Earth where they claim I do; but let's not talk about that. It's passed. And so is the Fourth Tenor business, thank God. It was useful for my career to be linked with Pavarotti and the others, but also dangerous - when they had so much more experience - to make me the d'Artagnan to complete the group. Unfair to me, unfair to them." And the sex? "That was dangerous too, for obvious reasons. Calling me the sex symbol of opera was easy journalism, and maybe now I'm nearly 40 this is over. Not long ago I was conducting a concert and produced my spectacles: I need them these days to read. The audience laughed. I said: well, there's a time for everything, and now I have spectacles maybe you will consider me a serious musician." It's an understandable response although, as opera colleagues will tell testify, Cura is not insensitive to how he looks. He has a face that changes totally according to the angle of perception. To the side it has a chiselled sharpness. Straight on it's more ordinary, with a Near Eastern heaviness that says something about Cura's background. Born in 1963 in Argentina, he is Latin to the core. But in the distant past his father's family came from Lebanon: hence "Cura", an originally Arabic name converted into Spanish. His initial interest in music wasn't singing but composition (he still writes but isn't published), and he didn't take his voice particularly seriously until the age of 26. "I enrolled with the opera school at the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aires but only stayed two months because things didn't work out. They said I wasn't born to sing. But I did carry on in the chorus - from '84 to '89 - simply to earn a living. These were bad times in my country, you did what you could. I never thought of myself as a solo singer: I just wanted to compose." Eventually he and his wife decided to chance a new life in Europe. "We sold our apartment to pay for the tickets and spent the next six months leading la vie boheme. Very basic. What we got for that apartment was what is now my fee for one evening." Settling in Italy, he started to get significant work in the early 1990s. The big breaks came in 1994/5 with a competition victory and the tenor lead in Verdi's Stiffelio at Covent Garden. But this was not a sudden stardom. "And so much the better: I learned my craft, and when things happened it was the right time. I was young enough to be of interest to the world, but old enough to keep things under control. I had a wife, children, responsibilities, and a philosophical perspective on life you don't have in your 20s." That philosophical perspective may be just as well during the coming months because, bizarrely for a tenor at the top of his profession, his schedule isn't overloaded with high-profile dates and he has no recording work. His record company, Warner, quietly let his contract lapse three months ago - for reasons both sides are at pains to call "amicable", but even so, this is an odd turn of events for the man they called the Fourth Tenor. The Sexy Tenor. More explicable, perhaps, if it's connected with that other label. Arrogant. During our interview, he doesn't come across that way. He's obviously shrewd, determined, with emphatic business sense (he runs his own production company) and considerable self-belief. But, as he says, why not? He also knows the value of a spot of controversy. As we part he tells me he is Oscar Wilde's disciple. "Better to be talked about than not. So talk." I promise that I will.

|

|

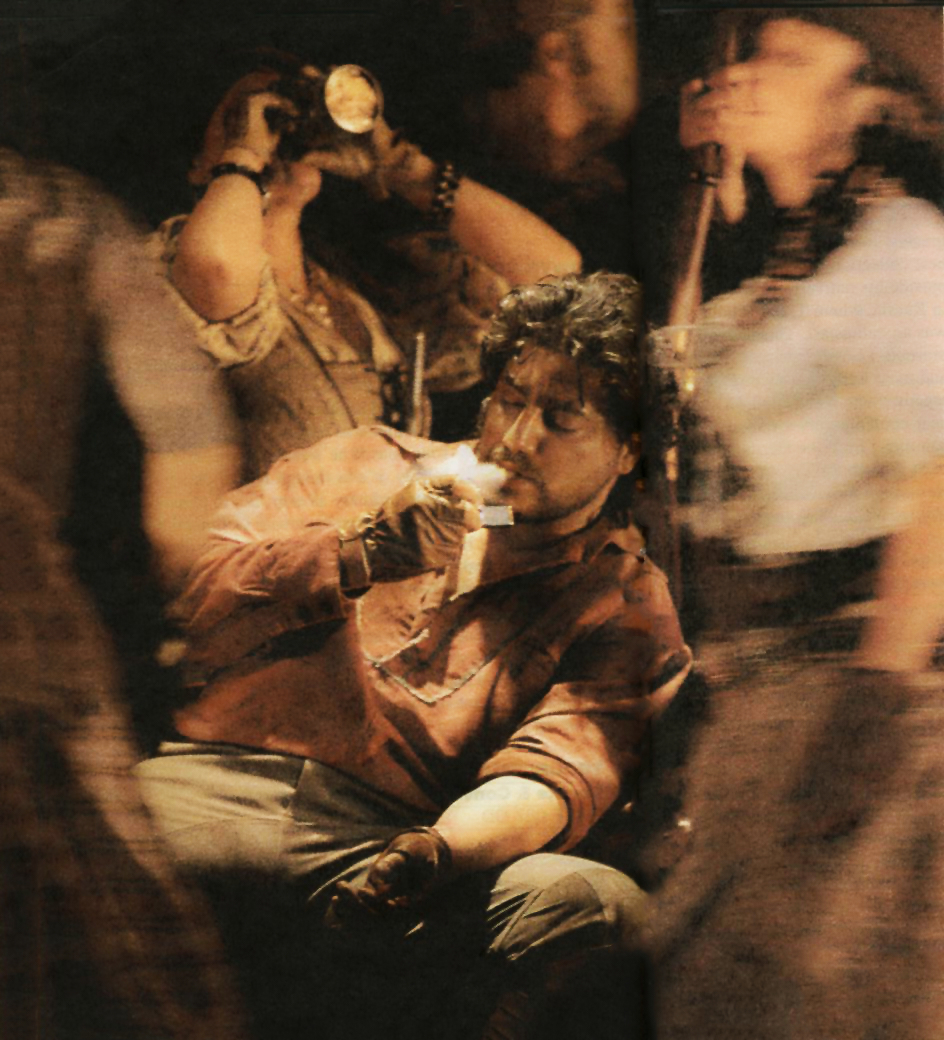

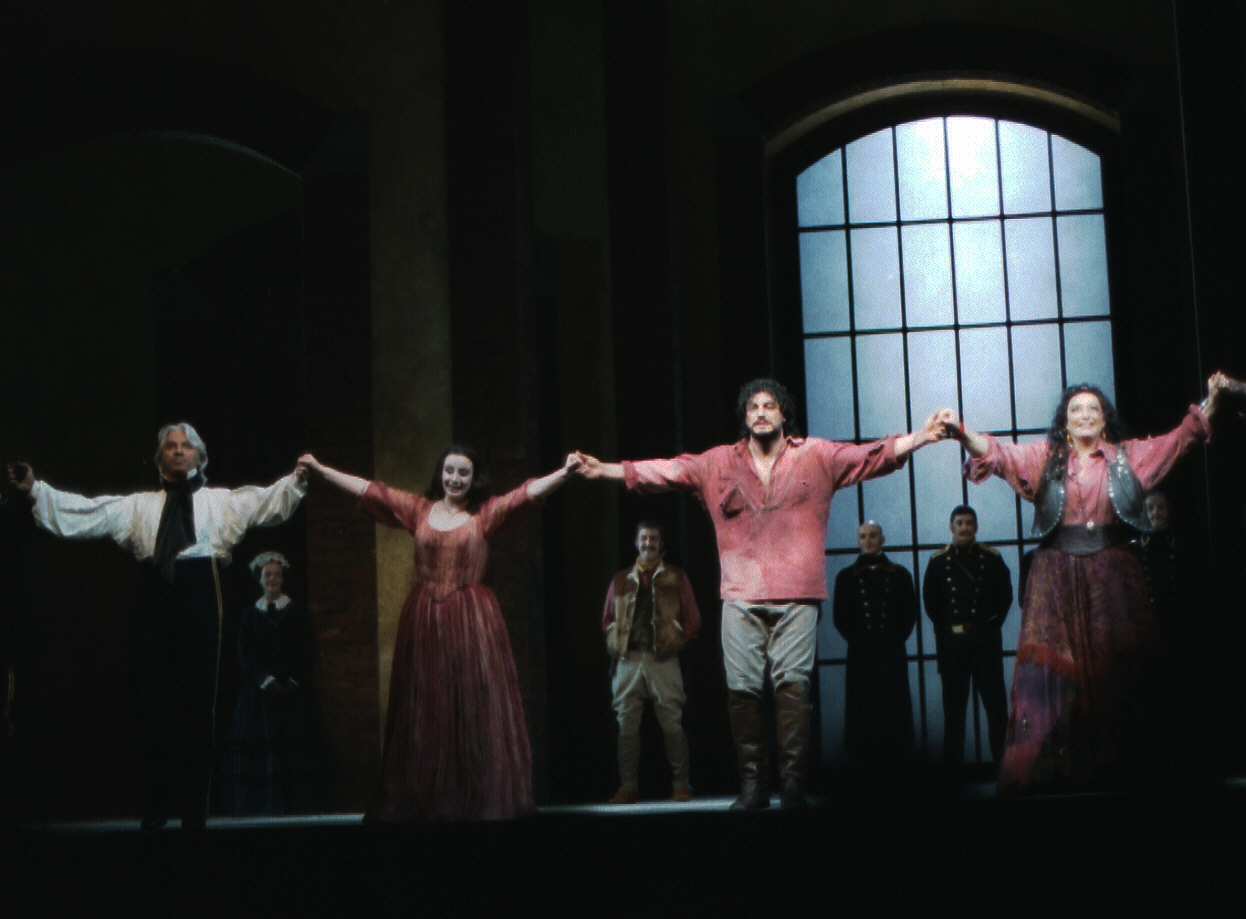

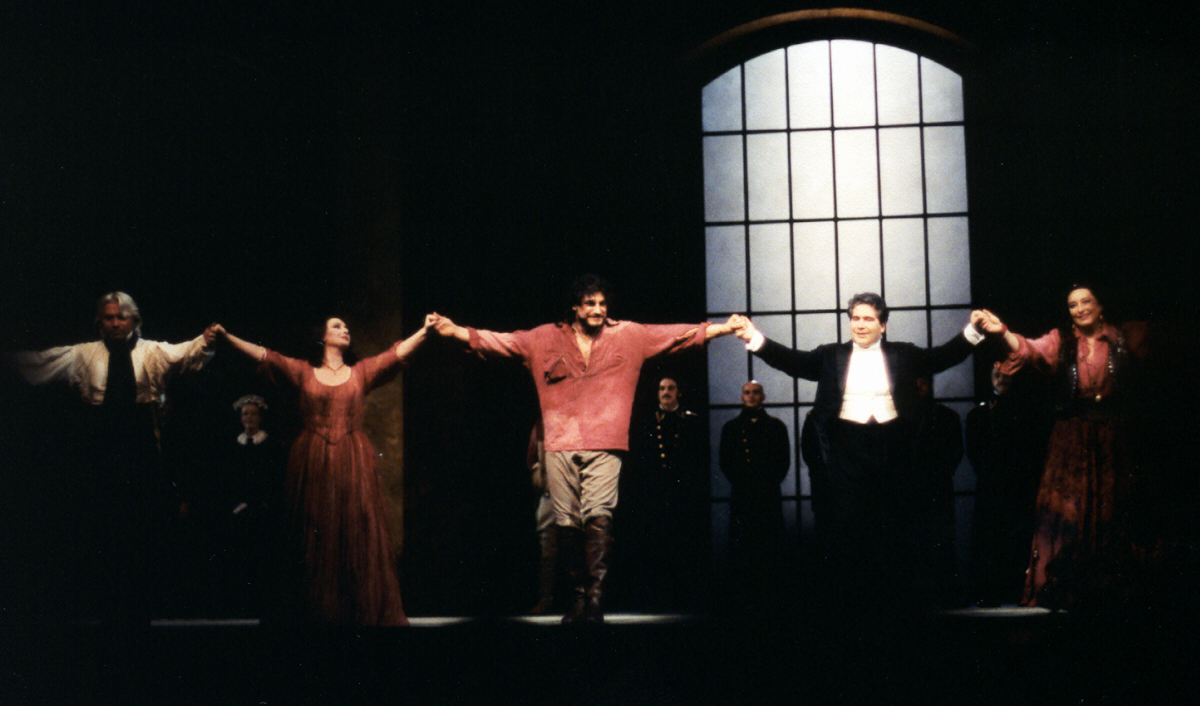

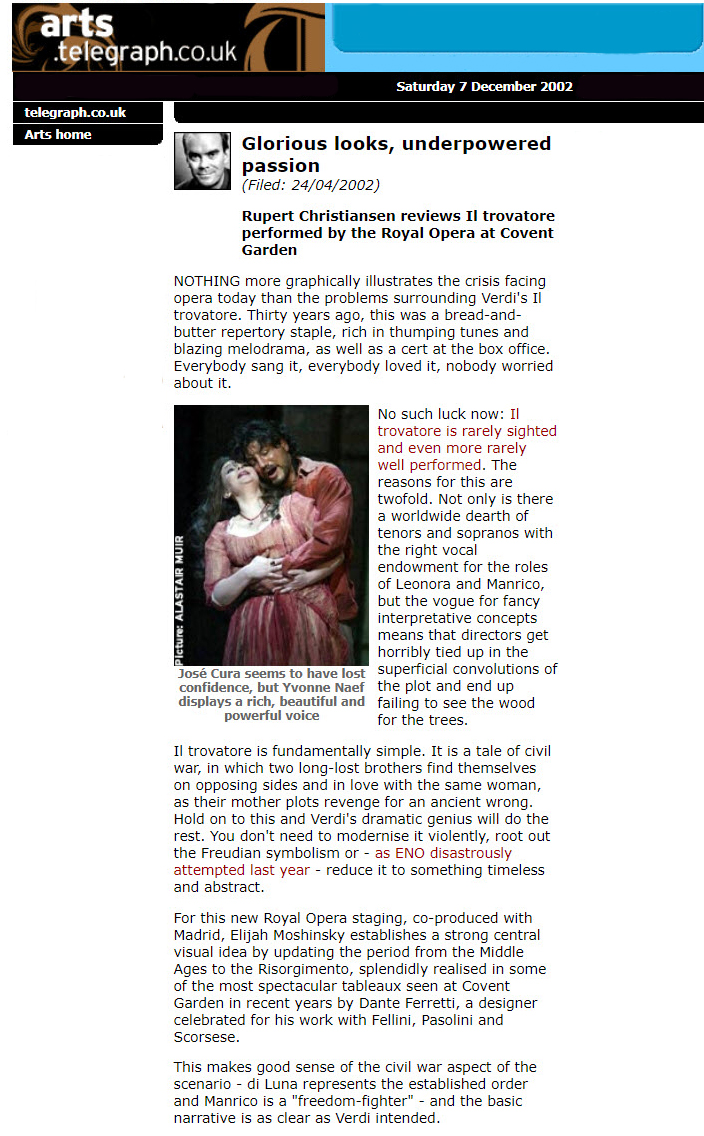

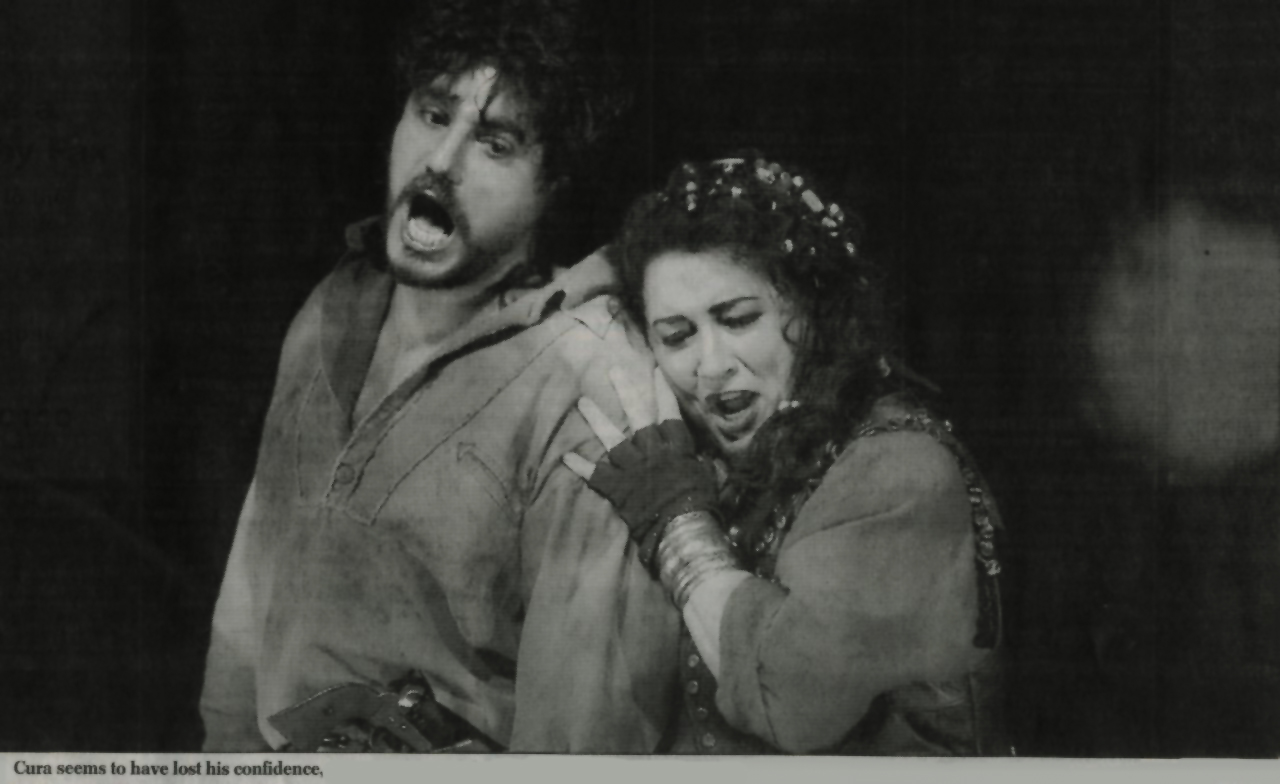

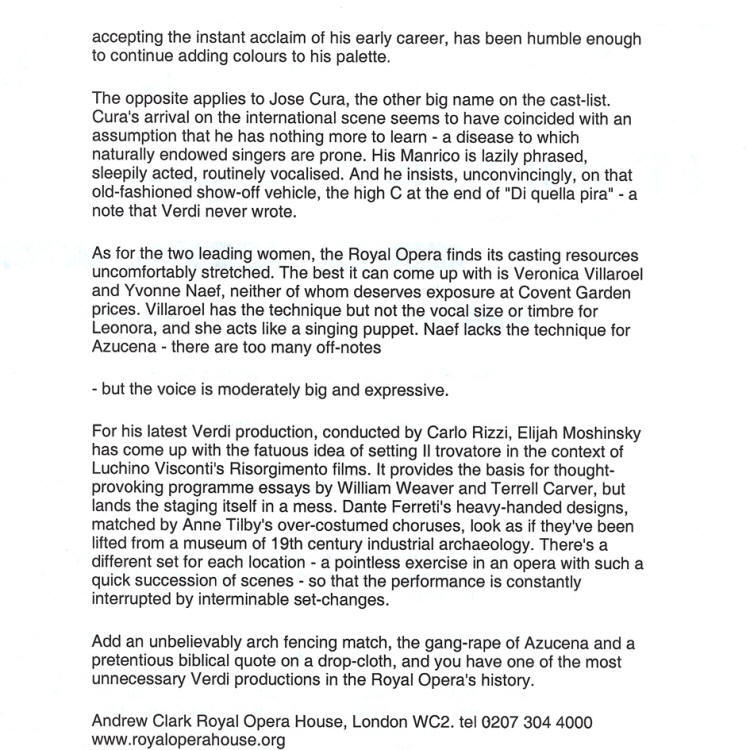

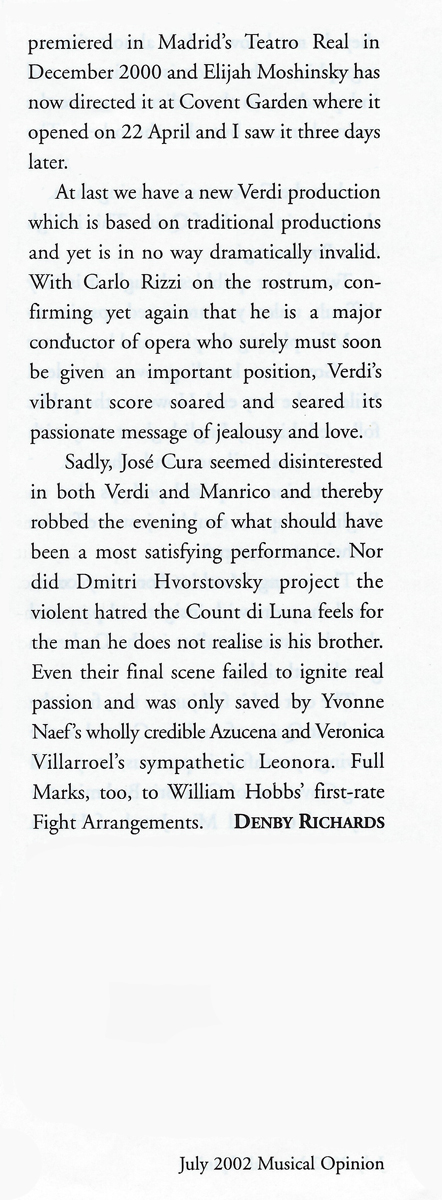

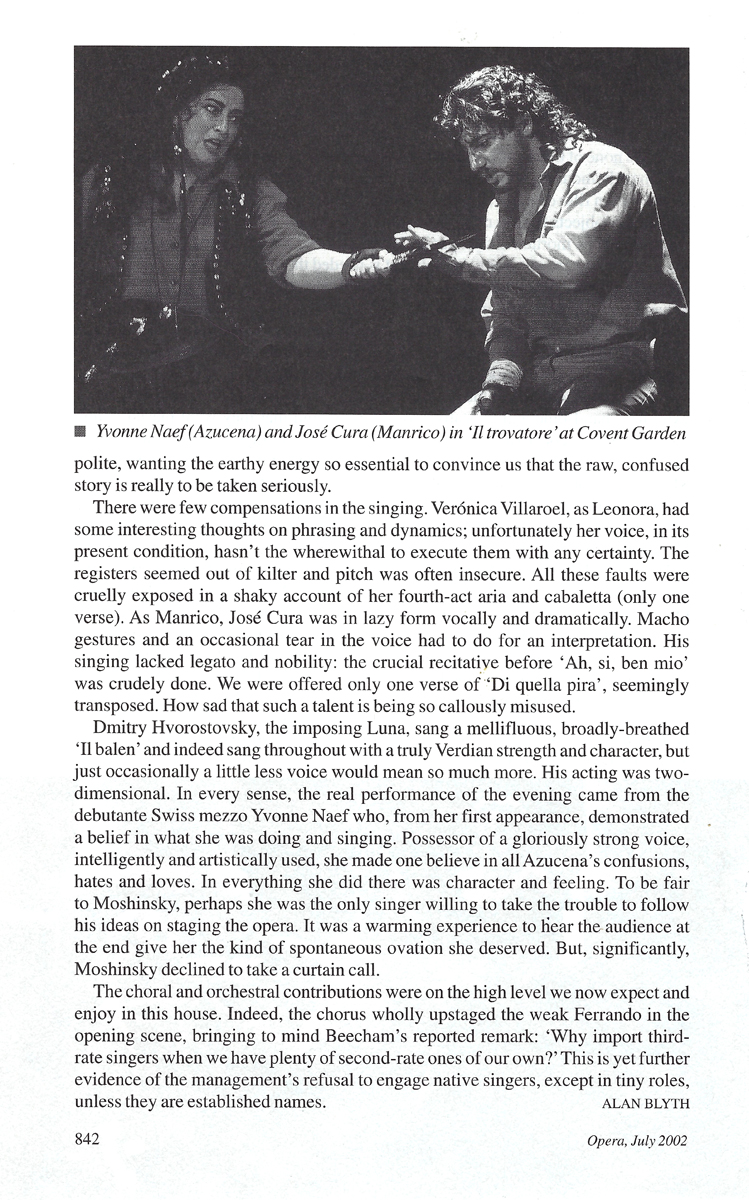

Il Trovatore at Royal Opera House Opera News George Hall Given Caruso's famous dictum that Il Trovatore requires nothing but the four greatest singers in the world, one supposes that the difficulty of coming up with an effective cast for Verdi's revenge tragedy is not new. Covent Garden's latest attempt (April 22) was certainly more presentable than most. It was played out within Italian film designer Dante Ferretti's expensive-looking sets, which exchanged the location and period of the work's setting (medieval Spain at a time of civil war) for that -- more or less -- of the opera's creation: the sullen, ultimately heroic Italy of the Risorgimento. The show boasted what surely must be some of the most realistic fight scenes ever seen on the opera stage (arranged by William Hobbs). José Cura's Manrico and Dmitri Hvorostovsky's di Luna went at it tooth and nail, if not hammer and tongs, and again and again one feared for their diaphragms. Cura's Manrico was an outstanding achievement, technically unimpeachable (he crowned "Di quella pira" with a couple of formidable top Cs) and often elegant. Taking all four phrases at "Riposa, o madre" in the final scene in one breath not once but twice is going beyond the call of tenorial duty. Such diligence helped him create a character of alternate bravado and lassitude, a romantic hero doomed from the start to failure and ignominious death. As di Luna, Hvorostovsky was equally fine, fleshing out the lines of "Il balen" grandly and deploying a wide variety of tone throughout to marvelous effect.

|

|

|

|

Il Trovatore Daily Mail David Gillard 2 March 2002

Caruso once said that Verdi’s gloriously tuneful thud –and-thunder romance called for “the four best singers in the world.” And certainly the opera’s leading quartet—Manrico, the rebellious troubadour of the title, his deadly adversary the Count di Luna, his lover Leonora, and the mysterious gipsy Azucena, his supposed mother—are all formidable roles. OK, the Royal Opera’s imposing new production does not field a foursome that would quite fit Caruso’s demands. (Well, which company could?) But in the elegant Manrico of José Cura, the noble di Luna of Dmitri Hvorostovsky, the refined Leonora of Veronica Villarroel and the chilling Azucena of Yvonne Naef, they have a cast to queue for. There is vocal power here to match the grandeur of Dante Ferretti’s massive sets and Elijah Moshinsky’s crackingly paced staging (interrupted only by some tediously lengthy scene changes). Moshinsky wisely confronts this elaborate plot head-on. Instead of trying to make sense of its notorious complexities—mistaken identity, love and lust thwarted, gipsy curses and brothers parted amid a ranging Spanish Civil War—he just tells the tale. It doesn’t always work. The visual aberrations include the transforming of Leonora’s convent into what might be a Victorian railway station, while the gratuitous, black leatherclad dueling scene is laughably camp and should be run through forthwith. But Verdi’s passionate and melodious score, played with real refinement under conductor Carlo Rizzi, always underpins the occasion and, with the Big Four, keeps the evening nicely on boil.

|

.jpg)

|

|

Opera Japanica

Ruth Elleson

January 2003

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

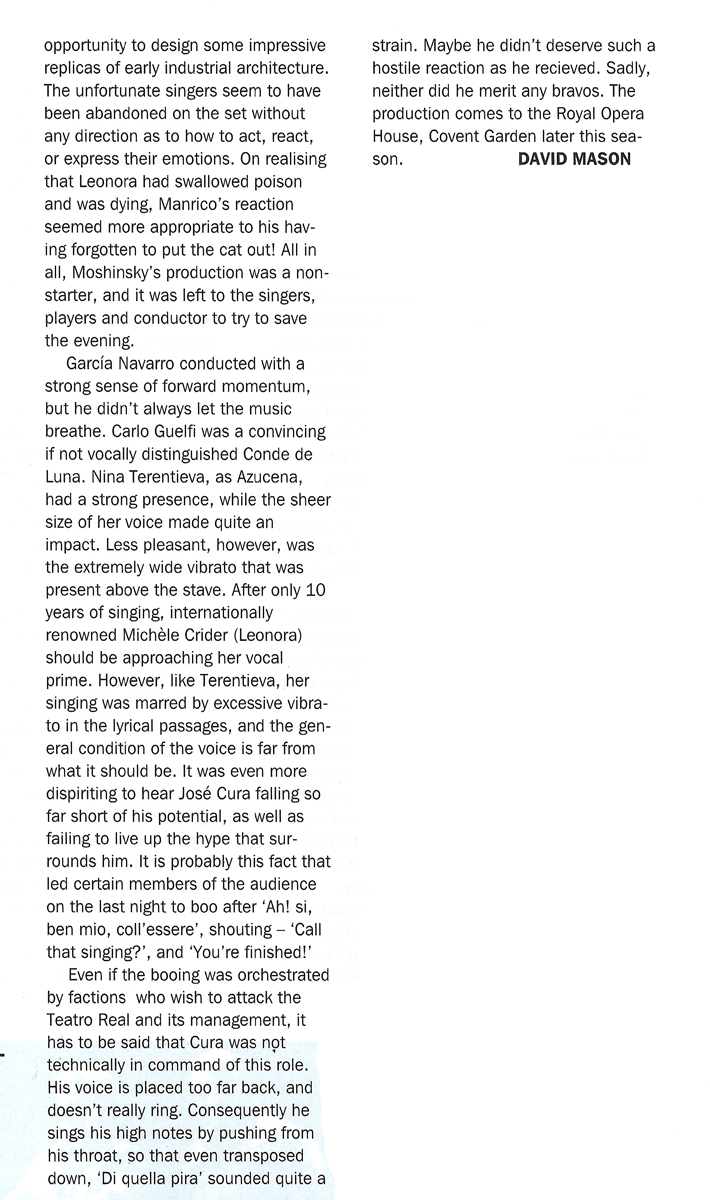

No way, Jose

The new Domingo? Judging by the Royal Opera¦s tedious

Il trovatore, Jose The Sunday Times Hugh Canning 28 April 2002

The Royal Opera¦s recent roll obviously had to come

to an end sooner or later, and it does so ˜ resoundingly

˜ with the production of Verdi¦s Il trovatore it

has staged in collaboration with the Teatro Real,

Madrid, where Elijah Moshinsky¦s grand but plodding

mise en scene was unveiled 15 months ago. The central

panel of Verdi¦s celebrated "triptych"

of mid- period operas, the others being Rigoletto

and La traviata, Il trovatore was, until quite recently,

one of the most frequently performed of all operas.

In the past 20 years, it has become almost impossible

to cast consistently at the highest level, as Verdi

singers with the weight of voice, beauty of timbre

and expansiveness of phrasing have become increasingly

scarce. Since Placido Domingo and Luciano Pavarotti

renounced the title role of the warrior-troubadour

Manrico, the heroic Italian-style tenor has become

virtually extinct, and the contemporary public is

asked to put up with no more than serviceable substitutes.

The Royal Opera fields the Argentinian Jose Cura,

now in his late thirties, who has for some time

now been ear-marked as Domingo¦s natural successor

in the heavier Italian repertoire ˜ but after his

hammy and vulgar Otello at Covent Garden last season,

and now this casual, coarse, stylistically anachronistic

Manrico, he doesn¦t deserve to be mentioned in the

same breath.

|

|

|