Bravo Cura

Celebrating José Cura--Singer, Conductor, Director

Operas

Montezuma and the Red Priest

|

|

|

|

|

OperaWire David Salazar 9 January 2020

The opera, which was written by Cura, is “apparently about” the birth of the Vivaldi opera “Montezuma” and will feature a wide range unique characters in conversation. The opera will star Donát Varga as Vivaldi, with Blaon Domonkos as Handel, József Gál, as Scarlatti, and Zoltán Megyesi as Filomeno. Other cast members include Matias Tosi as Montezuma alongside János Alagi, Katalin Károlyi, and Lászlo Borbála, among others. The opera will be in several languages with Cura conducting the Hungarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. In addition to the premiere of his opera, Cura is set to revive a production of “Nabucco” later this season at the National Theatre of Prague as well as take on the role of Samson in “Samson et Dalila” at the Wiener Staatsoper. |

|

|

|

|

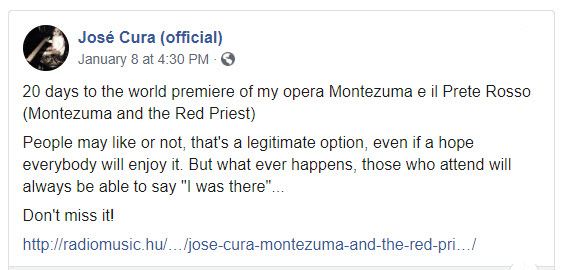

Words by José Cura About the libretto As said, Montezuma e il Prete Rosso is based on Alejo Carpentier’s novel. Or more aptly, inspired by it. In fact, many moments, such as Montezuma’s explanation of the events that led to his death, for example, are not part of Carpentier’s book and needed to be added for obvious dramatic reasons. Therefore, consulting other sources like the Codice Durán by Diego Durán, Historia verdadera de la conquista de Nueva España by Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Segunda carta de relación al emperador Carlos V by Hernán Cortés or Relación breve de la conquista de la Nueva España by Fray Francisco de Aguilar, was imperative. Apart from those historical texts, during the writing process, I felt the need to include a tribute to my beloved Shakespeare, by quoting a fragment of his Romeo and Juliet, extracted from Act I, scene 5, more precisely the verses during which a party is being prepared, and the Innkeeper runs up and down in search of the lazy Potpan. But if there is one big license I took, that would be the insertion of the Stornello: men and women challenging each other to see who comes up with the cheekiest limerick. Based on two 14th century poems, the titles of which are quoted in Bocaccio’s Decameron, it took me a long time to research, and finally discover, the full text of these two elusive rhymes, which I found in the book Cantilene e ballate, Strambotti e Madrigali by Giosuè Carducci. One defining decision for the libretto’s development was to settle on its main language. Having people communicating in Italian over a Spanish subject, like in Verdi’s La Forza del destino, or in German over an English story, like in Wagner’s Parsifal - two examples among countless more - was surely a possibility but, while this was almost sine-qua-non in Verdi and Wagner’s times, today’s librettists have more of a carte blanche to handle this, not so indifferent, dilemma. I remember when I turned 50 back in 2012, we organised a party with some of my dearest friends which - as is inevitable given my having lived in different countries, and being blessed as a result with amities from each one - ended up making my house sound like a cacophony of international proportions… However, to my surprise, even if everyone was speaking their own language, using some of the funniest gesturing in an effort to be understood, they all managed to communicate in the end. Yes, there were some misunderstandings, but these were part and parcel of what made the event fun: comedy was served. Based on that personal experience, and also wanting to experiment with the comic possibilities that a multilingual approach would allow, I decided to let all of the characters in the opera express themselves in their own mother tongue, as they would have done according to their backgrounds. If this had been a more realistic piece, and not a madcap comedy, one could argue on the specific technicalities of how they would have properly understood each other. But the clash of languages here serves the nature of the piece better than one single uniform tongue would.

|

|

|

|

[...]

|

Translation endorsed by José Cura:

"I Share Migration Hopes and Concerns"Exclusive Interview with Composer José CuraKepmasFanni Black26 January 2020

The first opera of composer-conductor-tenor José Cura will be performed at the Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music in Budapest. Montezuma and the Red Priest – A Comedy (But Not So Much), as its title suggests, serves not only to make viewers laugh but also raises issues as serious as the fight for equal opportunity. The Argentinian-born artist himself went on a difficult journey to obtain European citizenship.

Q: Why did you choose Hungary as the venue for the world premiere of this piece? José Cura: I am currently working with Hungarian Radio Art Groups (from 2019-2020, Cura is a permanent guest artist at MRME for three years - editor) who are my artistic family, so when I was considering my premiere I asked them first what they thought about it. They immediately agreed to my idea, so we are set to stage Montezuma together. Q: What is the cooperation with the musicians of the Hungarian Radio Symphony Orchestra and the Choir like? José Cura: Working with Hungarians is very interesting, I could describe it with the words "dangerous" and "fiery." They are quite temperamental, which I really like about them. Apart from the orchestra, they also have other work, such as teaching, so they are quite busy and sometimes they come to rehearsals already tired, so you have to keep that in mind. This is our second collaborative job and I am getting to know them: I already know who is married, who has a child, who has a problem… I turn to them not as a maestro but as a friend, which I consider essential in a community. Q: How did you choose the musicians for the roles? José Cura: It wasn't my job, the orchestra's artistic director was responsible for it. I knew most of them from before and we had already worked together two months earlier when we were preparing for the first rehearsals of the piece. Because of the multifaceted nature of the characters, it was a challenge to find the right people. For example, Vivaldi was not only a composer but also a violinist, so I needed a tenor who could play the instrument to perform the role. We are very lucky with Donát Varga, who is a great violinist and tenor in one person. Q: The story begins with a Mexican baron, a lord, traveling to Venice where, during the carnival, he dresses as the Aztec ruler Montezuma and meets Vivaldi, who in turn writes an opera about the Indian king as a result of the encounter. How do you bring the audience back to the 1700s? José Cura: The language of the opera follows the aesthetics of the Baroque: a small band of only forty people on stage, which makes the text more flexible. In contrast, during the romance age, the whole orchestra played during recitativo or dialogue, sometimes interrupting its continuity. Baroque, by the way, is my favorite era in music history, and I am a big fan of Bach. He is the alpha and omega of music, but Vivaldi, Händel and Scarlatti are also close to my heart. Q: To make the show livelier, the characters speak their native language. Do you speak each of the actors' dialect? José Cura: More or less, yes. My mother tongue is Spanish and I also speak English. I lived in Verona for four years but not Naples but I learned the Venetian dialect. Of course, there will be subtitles during the performance so the audience will understand every word of the characters. Q: Montezumá is based on the short novel Concierto Barroco by Alejo Carpentier, which you first read 30 years ago. Why did you wait so long for the work to be staged? José Cura: I found the book a great literary work at the time, seeing the potential, but I was only 27 and didn't know how to begin. When it came back into my hands much later, everything became clear to me, thanks to my experience over the intervening decades. The story's important characters are composers, so it was logical to turn it into an opera and not, for example, a movie. Q: Despite his comedy genre, Montezuma begins with a tragedy: Francesquillo, a servant of the Lord, dies of plague. In a later scene, Vivaldi, Händel, and Scarlatti talk in a cemetery where they bid Wagner a farewell. How do death and comedy fit together? José Cura: You can die with humor. (laughs) If death is perceived as a sad event, it has no place in a comic opera, but instead of it being a romantic element, I see it as development, a transformation. Francesquillo's death is a symbol of a small child's metamorphosis: the plot begins with a young boy and ends with a man older than he, Filomeno, the servant being reborn in his soul. Later, Filomeno transforms the moral thread of the story. To get to that scene, Francesquillo had to die. Q: In the sixth act, the Lord questions Vivaldi for not being historically authentic, but the composer proclaims the primacy of the poetic illusion instead of facts. Which do you consider more important in art? José Cura: I believe in the golden mean: we must allow space for fantasy without distorting reality. Personally, I love realism onstage, but this opera is different because the novel on which it was based was written in the genre of magical realism typical of Latin American literature. Carpentier toyed with the idea of what it would have been like if Vivaldi had written a piece in the present day, parodying the fashion of the Baroque era, such as a lot of songs sung by women. Q: Did you use other sources for the libretto? José Cura: Because of the limitations of scope Carpentier does not elaborate on who Montezuma was, so I read historical texts and chronicles of the Aztec ruler, such as the writings of Bernal Díaz del Castillo and Fray Francisco de Aguilar, but these are only theories and do not reveal the whole truth. I've incorporated the most dramatic approach into the story. When you write a play, you need different characters on stage; instead of the disputed texts, I relied on paintings and my imagination to create the characters' personalities. Looking at pictures, I was trying to figure out what kind of person each might have been. Based on this, I imagined the chunky Handel to be a kind, lovable figure, while I thought of Vivaldi as having an elegant and sophisticated look that concealed an endearing interior. Q: Who's your favorite character? José Cura: The servant of the Lord, Filomeno, who follows him after Francisquillo's death, and just like Pinocchio's little counselor, he listens and comments on everything. Although not musically, from a moral point of view he is the most important character: the evolution of the story is in his hands. Due to the color of Filomeno’s skin, the issue of human rights is raised several times in the opera, which is why the title of the piece became "comedy - but not so much." Q: The story ends with the Lord's decision to travel back to Mexico and releases Filomeno, who is trying to get lucky in France. Can he thrive there as a famous trumpet player? José Cura: The servant is going to Paris with the hope that he will be called Monsieur Filomeno there, and will not be called "the Negro.” When he hears his desire, the Lord says that this may change one day, to which Filomeno replies, "If you say so..." It leaves the question open, and it is not my job to answer it, the audience must draw the conclusion for itself. I do not think it is a good idea for the author to explain the ending, because then the viewer just goes home, drinks a cup of coffee and forgets what he has seen. It's more exciting if you have to figure it out yourself. In this case, they're going to think about it for a long time, and it starts conversations about how to interpret the performance. Q: How do you see the issue of human rights? José Cura: Racism is still present today, and the problem of migration is causing much debate in Hungary and throughout Europe. Politicians, to divide society, make everything black and white, but this is a much more complex issue. I have nothing to say about it. I know both sides of the coin: at the beginning of the last century my grandparents migrated from Italy, Spain and Lebanon to Argentina, and I was born there. Thirty years ago, I came to Europe. Migration between continents is a natural cycle: we go from one point to another and we cannot tell where we will be in a hundred years. I sympathize with the situation of those on the road to a better life, but I also understand the concerns of Europeans, who are frightened by the masses of people coming to their country. The uncontrolled admission of immigrants is not good for them or for us: we must provide them with work, hope, dignity, because being on the streets begging is not dignified, but an attack on migration. The only thing I cannot tolerate is the lack of education and compassion; with violence, neither side achieves its goal. Q: How do you remember the time you came to Europe? José Cura: In 1991, I waited at the police station, in company of Africans, to be granted a residence permit to three months, and every three months I had to go back to claim a new one. It took me over 15 years to establish my life here, like getting a European passport. These things also affected my career: I wanted to travel to England before the Schengen Convention, and I had problems with my Argentinian passport, and when I wanted to return to Italy, I was rudely received by the police at the border. I know what it is like when immigrants have no money to eat and can't find work. One time someone wouldn't hire me because he was convinced that all Argentines are thieves. Over the past 57 years of my life, I have had many dramatic but beautiful moments, and these experiences have made me who I am now. Q: How important is South American culture to your life? José Cura: Every culture is important if you want to be a good artist. Of course, it is impossible to embrace all of them, but we must strive to at least discover the cultures that surround us or represent our characters. Thanks to my ancestry, I understand the Spaniards and the Italians, but also the Arabs, the Lebanese. Q: What is your relationship to Hungarian culture? José Cura: Although I have been coming to Hungary for twenty years, during my visits I spend only a little time here with no opportunity to sightsee. Right now I'm commuting between the Academy of Music and the Radio building and the National Museum is between the commute, but we work 10 hours a day so by the time we are done, it is closed. But in a few months, I may be able to give a different answer to the question. As a guest artist of MRME, I have a closer working relationship with the nation, so I am slowly getting to know Hungarian culture and life and am no longer seen as a guest. Q: The audience will first see the fruits of their joint work on January 29th. What kind of welcome do you expect? José Cura: I can't tell you that, but I trust they’ll love it. If there is no booing, that's good feedback. (laughs) Q: Who is the audience for the comedy opera? José Cura: This is a very clever and dangerous question! (laughs) Montezuma is for a wide audience. This is an intellectual comedy opera that contains many references to other works. The audience will have fun even if they have no prior knowledge of them, but the play becomes most enjoyable if they recognize the hints. The same goes for other branches of art: if you go to the Louvre without hearing about Mona Lisa before, you will only see a smiling lady, but if someone explains the underlying meaning behind it, the colors, the use of the brush, the thoughtfulness of the picture will make more sense to you. Awareness makes for more fun. Q: What references did you hide in the opera? José Cura: In his book Carpentier cites many musical works as he was also a music historian. In Montezuma, in addition to Vivaldi, Händel and Scarlatti, we cite works such as Verdi’s Otello, Igor Stravinsky's Circus Polka, and for twenty seconds a piece from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. We also refer to Walt Disney as a joke, juxtaposing his tales with Wagner's fantastic world. Q: Montezuma is your first opera. Why has composing previously been neglected in your career? José Cura: As a tenor, I give a hundred performances a year, with no time left to compose. Composing is a full time job. When I orchestrated the music of Montezuma, I spent weeks in the studio, talking to no one, and the outside world disappeared for me. Q: Do you plan on composing more pieces in the near future? José Cura: I'm looking for another libretto, and I hope it won't be thirty more years before I find it, because that would be too late. (laughs) Today, the music is not the greatest challenge but finding the perfect libretto that interests people.

|

|

Photos from Article

|

|

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.

Partial translation

JOSÉ CURA: MONTEZUMA AND THE RED PRIEST Symphony Orchestra of the Hungarian Radio José Cura: Montezuma and the Red Priest - Comedy (but not so much) [Premiere - semi-staged performance]

“In 1988, for my birthday, I received Alejo Carpentier's novel Concierto Barroco (in Hungarian: Baroque Music). I read it quickly and found it so interesting that I scribbled the volume with my comments. At that time, at the age of 26, I had no idea how to compose an opera. The book got dusty on my shelf for 29 years until, in 2017, when it was reorganizing my library, it just suddenly fell out in front of me. I re-read it and decided to make a comedy from the novel. Montezuma and the Red Priest became the title; ‘It’s a comedy, but not so much,’ I wrote as a subtitle, trying to suggest that the story had serious implications. I put the libretto on paper in one afternoon, and in the summer of 2017 I composed the music for it. The orchestral version was completed in the summer of 2019,” José Cura said of his work. The novel, which is the basis of the opera, is about the birth of Vivaldi's opera Montezuma, giving a huge space to the writer’s imagination.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Rehearsal Photos

|

|

|

|

Narrator's script Words by José Cura

Narrator: (voice off): Good evening! My name is Adam and I will be your host tonight. Actually, I exist only for this concert so that you can follow the story surrounding the music, even if you won’t see the action this time around. Also, when the actors sing, a Hungarian translation will be automatically shown in the surtitles area right above the stage, and whenever I narrate the events in Hungarian, a translation will be shown (as you can see right now) in English, for the non-Hungarian audience to follow. Enjoy and, once more, don’t forget to turn off your phones!!!

The year is 1732, and we find ourselves in Mexico, more precisely, in the city of Veracruz. The Baron, the grandson of Spanish immigrants who forged their family fortune during the silver mine boom, decides to travel to Europe for leisure. An amateur baritone, but with aspirations to one day become a great singer, the Baron is observing Francisquillo, his young servant, as he packs their bags for the long trip ahead, when he quickly realises the boy is suffering from a serious toothache. He offers Francisquillo a drink in the hopes it might help soothe his pain. Suddenly, one of the Baron’s lovers rushes in pretending to be afflicted by some sort of premature sense of longing for the Baron, before he’s even set sail for the old continent. Her real intention being to hopefully receive an expensive present from her lover. In order to calm the woman’s manufactured hysteria, the Baron presents her with an expensive necklace, as Francisquillo sings her a traditional Mexican children’s song. There is a knock on the door, and two unexpected visitors offer the Baron a beautifully folded manuscript. The Baron unfolds it, revealing a long list of gifting requests for him to bring back home from abroad: “And if you happen to pass by Paris, can you bring me that delicious perfume that…?” or “Please, don’t forget to buy me a mask if you find yourself in Venice during the Carnival!”, and so on and so forth, down the endless list. The angry Baron refuses to become an errand boy and retires to his bedroom with his lover in order to work through his anger… Meanwhile Francisquillo decides to make fun of the situation, singing Monteverdi’s “Oh, dolente partita” (Oh, sorrowful departure). While this beautiful music develops —a piece which is in fact about the departure of someone in death, and not that of a leisurely trip— we discover that our heroes have arrived in La Habana, Cuba, in the middle of the smallpox epidemic that is devastating the city, in order to board the ship headed across the Atlantic over to Europe. The Baron and his servant seek refuge somewhere they can safely spend the two weeks they have to wait for the ship to arrive. While doctors are taking care of the many infected by the disease, and the corpses of those who haven’t been saved are being thrown onto a chariot to be cremated, the choir sings funeral music. Fate wants Francisquillo, young and weak as he is, to get infected by the pox. A local Cuban man finds himself taking care of him, but the boy worsens, and dies. The Baron, now in sudden need of assistance during his trip to Europe, employs the services of “el negro Filomeno”, Francisquillo’s accidental nurse, who takes the place of his now deceased servant.

The Carnival The Baron and his new servant Filomeno arrive in Venice during the Carnival of 1733, where they discover that the muffled racket of cymbals rattles, drums and Venetian cornets do not differ much from the cacophony of a Caribbean party. Not to be outdone, the Baron decides to dress up, as Venetians are wont to do during the yearly festivities, and short of a better idea, he decides on adopting the likeness of legendary Aztec Emperor Montezuma. Filomeno, on the contrary, decides to proudly sport his looks without any artifices. Having eventually grown tired of the street fare, the Baron and his servant step into a Venetian bottega in order to refuel. Fate wants them to share a table with a mysteriously dark, and elegant figure: violinist and composer Antonio Vivaldi, the Red Priest himself. The Venetian quizzes the Mexican Baron over the legendary Aztec emperor, whose garbs he is donning, when a small orchestra arrives to entertain the bottega’s patrons. The host, quoting a passage from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, sets up an area for the musicians, but when the players realise they are in the presence of the legendary Maestro Vivaldi, instead of playing the joyful popular music they were paid to perform, they decide to pay tribute to him, playing on of his compositions. The host apologises to the great composer, trying to explain rather pathetically why his beautifully refined music doesn’t fit the mundane setting of a street-level bottega, but an offended Vivaldi proves, with a musical outburst, how his art could indeed suit any time or place, if he so wished it to. The musicians, ashamed with the turning of events, begin to play a shy Minuet, as a very angry Georg Frederick Händel, followed by the lighthearted harpsichord virtuoso Domenico Scarlatti, erupts into the establishment. Vivaldi invites the two men to share his table, and the conversation turns towards Händel’s recently premiered opera, Agrippina, at the Teatro Grimani. A few drinks in, everybody relaxes, and the real party starts when a joyful Gavotte takes over the languid Minuet which was being played until then by the orchestra. The party ends with a sudden contest between men and women, hoping to determine who among them can come up with the cheekiest limerick. Based on two mischievous 14th century poems, the Stornello leads to the fourth scene.

The Hospice Still excited by the party, and looking to unwind, while the Carnival continues in the background, Vivaldi invites his friends to visit the Ospedale della Pietà, a historical hospice for orphaned women, in which the nuns would give their protégées a start in life by teaching them how to play an instrument. Vivaldi, a teacher himself at the hospice, is openly welcomed in by the orderly nun. He warmly introduces his pupils to his friends. Scarlatti sits at the harpsichord to play his latest composition as Vivaldi joins, violin in hand. A memorable musical moment takes shape with everyone participating until Händel, responding to Vivaldi’s provocation, explodes in a fearful rendition of his famous Alleluia, blanketing everyone with an overpowering flow of sound. Filomeno, who had gone out in search of an instrument that suited his abilities, rushes back, sporting a couple of cooking pans which he starts banging loudly, hushing everyone. The composers, delighted by the sudden turn in musical style, unite in an unexpected jam-session over Händel’s Alleluia, but after a while, Vivaldi, always hungry for fearful acrobatics on the violin, screeches the improvisation to a halt with the motive of his Four seasons’ Summer Storm. Soon, everyone joins in again and the improvised excerpt of the famous piece ends with an outburst of exhausted laughter. Everyone is having fun, drinking and getting increasingly intimate when, out of the blue, Filomeno starts to sing an ominous melody, as he stares at a painting of Eve being tempted by the Snake in the Garden of Eden. The unexpected change of mood slowly leads everyone off to enjoy the night in each other’s company. Everyone except for the orderly nun who, not being able to join the group due to her chastity vows… finds solace in frantically beating the Peruvian cajón instead…

The Cemetery Having spent the night at the Hospice and the morning sleeping, in the afternoon, Vivaldi’s gang decides to head out for a walk through the town in order to clear their heads. A gondolier takes them to the gardens that grow in the cemetery of the island of San Michele. There, where gravestones seem to be the unset tables of a vast empty café, they hope to be able to peacefully consume the vittles gifted to them by the orderly nun. The story of Montezuma becomes once more the topic of conversation, letting Vivaldi’s enthusiasm emerge again. Determined to modernise the themes on which the operas of the time were based, the revolutionary Venetian butts heads with the more conservative Händel, even at the risk of offending him. During one of the many time jumps of the piece, Vivaldi uncovers Stravinsky’s grave, and Händel uses this opportunity to take revenge upon his friend, reminding him that the great Russian composer used to openly mock his music. Vivaldi retorts, saying that he at least doesn’t write music for elephants to dance to, as Stravinsky did in a Polka he wrote, which was commissioned by the Barnum Circus. Filomeno, innocently suggests they should perhaps write an opera about his grandfather, Salvador Golomón, a slave who’d fought a French pirate to the death, but Händel refuses, arguing that it would be impossible for a black man to be the protagonist of anything. Filomeno, proving to be more erudite than could be assumed from his rank as a servant, corrects Händel, pointing out that a play about a black man’s adventures during the Venetian’s war against the Turks, was proving to be an absolute success in London. The Baron reprieves his servant for overstepping his mark by openly correcting a man of a higher caste and the latter, distancing himself from the group, takes a trumpet out of his bag: a gift from Lucietta, one of the Hospice orphans. A distant funeral bell rings, and a Requiem begins to emerge from afar, sung by a procession carrying the remains of a famous German composer, deceased the day before in Venice, as explained by the monk who leads procession. Scarlatti explains that this was the man who wrote all those fantastically long operas in which horses could fly, dragons would spit fire and even women who could speak under water, and Filomeno, taken by surprise, asks if he is talking about Walt Disney… The group burst into rapturous laughter, before respectfully joining the choir in paying tribute to Richard Wagner.

The Rehearsal A few weeks have passed and Vivaldi, having finished the first draft of his opera Motezuma, spelled without an N as he himself named it, is rehearsing some of its recitativi. Händel and Scarlatti watch their colleague at work from one of the balconies, and the Filomeno, watches from the box opposite. The Baron, turning his singing dream into reality, is himself in charge of interpreting the eponymous emperor. The rehearsal unfolds, peppered by Vivaldi’s increasingly cutting remarks, and the Baron’s protests, unhappy with the historical inaccuracies so disrespectfully incurred by the authors. Eventually, a stirred up discussion takes place between the Baron and Vivaldi, in which the former defends the importance of historical facts, and the latter that of poetic illusion. Scarlatti and Händel, not wanting to take a side, leave the theatre to go out for a walk. The discussion grows increasingly intense and Vivaldi exits, offended by the Mexican’s alleged lack of sensibility. The Baron, fed up with this much arrogance and stupidity, decides to head back home to Mexico, to his true customs and affections, exempting his servant from his obligations in the interim. Filomeno decides to go to Paris, where he would be called Monsieur and not simply “the negro”, as he has always been referred by. At the end, we see “Monsieur Filomenó” alone on stage, playing his trumpet while in the background, posters advertising Louis Armstrong’s legendary concerts in Paris, are projected. |

|

Scenes from a Madcap Comedy -- but not so much!

Performance

Maestro, composer, librettist, director

//

|

|

Curtain Call Photos

|

Last Updated: Sunday, February 09, 2020 © Copyright: Kira