|

|

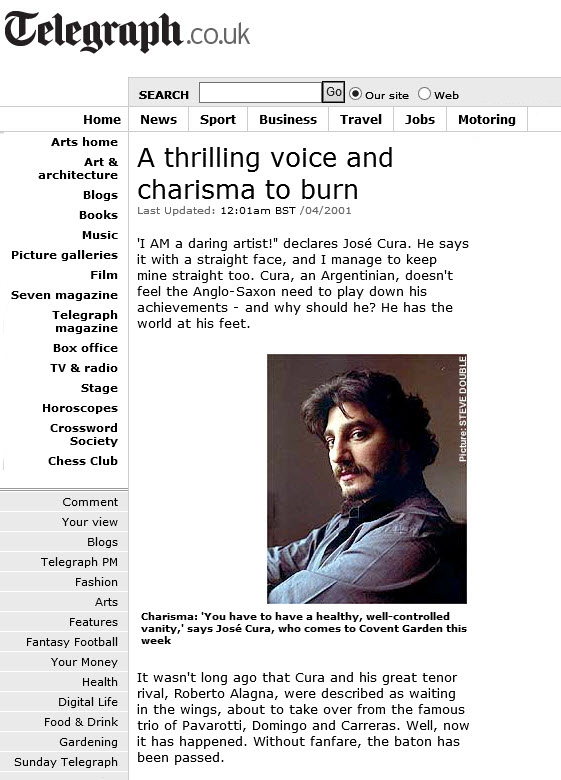

Bravo Cura

Celebrating José Cura--Singer, Conductor, Director

Operas: Otello

Otello - Turin / 1997

The First!

|

|

|

|

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.

Otello OperaWeb Marco Milano 11 May 1997 [Excerpt] This Otello was certainly intended to represents the peak of the current Turin season. The possibility of listening to the great Berliner Philharmoniker, undoubtedly the best orchestra in the world, conducted by Claudio Abbado, in an opera performance in our country represents an authentic "event," and we immediately say that the expectations were not only met but even exceeded by the performance of the Berliners. And certainly not to be overlooked were José Cura's Otello, Barbara Frittoli's Desdemona and Ruggero Raimondi's Iago: the first identified as Domingo's authentic heir, the second now consecrated as a fine performer with a beautiful voice, and the third authentic pillar of Italian musical theater as both vocalist and interpreter. All were encased in the poetic directional vision of Ermanno Olmi and with the participation of the excellent Coro del Regio, flanked by two other choirs. An inspiring picture which granted the discerning audience of the Regio an evening of extraordinary musical level, and whose results were almost perfect. Let’s explain the reason for the “almost” immediately: the Argentinian tenor José Cura provided a painful and intimate interpretation of great musicality, but a suffered and intimate interpretation, of great musicality, but the full expression of this interpretation was, in our opinion, affected by sensitive problems of homogeneity, which made the phrasing problematic, flattening it, and not very powerful voice. Cura is endowed with a wonderful low register, warm and sensual, its high notes are centered and ringing, but between these extremes the connection is precarious, and does not allow the pliability and ductility necessary for a fully satisfactory interpretation of the Moor of Venice, which also requires a burnished medium register and a total volume which the young South American tenor does not currently possess. Of course, the "introspective" interpretation made these shortcomings less evident, but a well-rounded Otello is another thing. Phrasing was, on the other hand, one of the highest points of Barbara Frittoli's very musical and moving Desdemona: a voice capable of a full, rounded forte like a pianissimo at the limits of audible but always alive and vibrant […] Such purity and ingenuity had their perfect counterpart in the cruel malice of Ruggero Raimondi in the role of Iago. Raimondi's theatrical skills are superlative, and every movement, every musical phrase, every glance dripped with hatred and perfidy. His Iago was rendered in total vocal and interpretative fullness. […] The Berliner Philharmoniker performed Verdi's score with unrivaled perfection: the precision of the ensemble, the coordination in the phrasing, the beauty of the sound, all contributed to making this orchestra the real star of the evening. The fullness and precision of the brass, the musicality of the soloists both between the winds and the strings (whose sound has an inimitable warmth), the tonal palette and the practically infinite dynamic range, deserve praise. Obviously the merit of this incredible artistic quality must be shared with Claudio Abbado. His reading of Otello is intimate and poetic, based on introspection, and even if this is not the interpretation of Otello we prefer, one cannot fail to admire the perfect coherence of this vision and its internal richness. The director's vision of the tragedy of jealousy was in perfect agreement with Abbado and with the interpretation of Cura, very intimate and introspective, slipping with wordless despair and desolate inevitability towards the final tragedy. In conclusion, we were delighted by an overall interpretation which, although not our preferred one for Verdi's masterpiece, showed a musical, vocal and visual unity of such a level as to represent a real gem in the current opera scene, especially for emotions transmitted by the dizzying perfection of the orchestral rendering.

|

Otello - Return to Argentina / 1999

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.

Now I Want to Succeed in Argentina Clarin Armando M Rapallo August 1998 He has been based in Europe since 1991. He has triumphed in the great theaters of the world. Besides being a singer, he is a composer. Next year he will debut at the Colón with Otello. He is 35 years old and a Newells fan. He is already a phenomenon, the up and coming tenor. In this century there have been Argentine singers of note, from Hina Spani, Isabel Marengo and Delia Rigal to Felipe Romito, Renato Sassola and Angel Mattiello, among many important personalities in their respective areas. But it is not easy to find—and not only among Argentine artists—a figure of the magnitude of José Cura, far beyond his triumph in the Operalia contest (in 1994, and with Plácido Domingo as president of the jury), and with an ascending career as meteoric as it is dazzling. The day after finishing his recording of Camille Saint-Saëns's Opera Samson et Dalila in London, directed by Sir Colin Davis and with the Russian Olga Borodina in the stellar female role, the Paris-based Rosarino tenor talked with Clarín. Clarin: You never liked the labels, the typecasting ... In fact, you never agreed to be the fourth tenor. José Cura: No way, please! I'm not the fourth tenor because I'm not even just a singer. I consider myself an artist who has been making music for a long time, as a composer, as a conductor and also as a singer. Also, I have other interests. My book on photography will be released shortly. Clarin: Your preference for acting is known. Did you really say you were an actor who sings, not a singer who pretends to act? Was that why you have waited for the recording studio? José Cura: At the beginning, yes, but only because I wasn’t able to transmit the experience, the sensation, to the maximum. The fact is there are still many people who judge an opera singer as if he were a record, trying to reduce the character to an abstract. In opera the different position is considered a great taboo. Let's remember the end of Samson et Dalila, where the central character is tortured and mistreated, and one voluntarily makes unorthodox sounds, more logical for the character because of what is happening to him. There are some critics who will point out the tenor's error in making the unusual sound, regardless of the sense in which it was emitted. Five minutes earlier they were praising everything, saying that it was a marvel. I prefer to modify certain results. In Otello, for example, I sing while lying on my back. I think that if you just want to hear the voice you can stay home with a whiskey and not go to the theater. That's what records are for. If you go to the theater you want a theatrical show, and I think this is the great challenge for the modern singer. Fifty years ago you went to the theater because there weren't so many records, no videos, and no TV. If by not sacrificing a phrase or a note we do not transmit direct emotions, the scene has no reason to exist. With regard to albums, José Cura's first CD, Puccini Arias, with the curious orchestral conductor Plácido Domingo, includes the most important things written by Giacomo Puccini for tenor (eleven of his twelve operas, naturally excepting Suor Angelica) and is a clear example of Cura's aesthetics, from the expressive eloquence of his diction in Non piangere Liú and his voice of singular power throughout the whole register. Cura-as-actor first of all reveals himself in his unsurpassed version of Firenze è come un alberto fiorito, from Gianni Schicchi and in the arias of Il Tabarro, where the full force of Puccinian verism emerges, creating a Liugi as ideal as Dick Johnson from La fanciulla del west, especially in the fragment Ch’ella mi creda. It is not risky to say that in the famous Nessun dorma from Turandot, José Cura now far exceeds the comparison with Pavarotti, Carreras and even with Domingo, for the purity of the emission, the impeccable placement of the high notes, the beauty of its lyrical spinto tone and the remarkable volume of a young voice, with a robust body like few others. Clarin: Tell us about your repertoire. José Cura: At the beginning of my career I generally accepted everything, but now, after taking on 30 roles in four years, I am in a position to negotiate with producers and theaters. I have already arranged with Colón to do Otello in the season next year. And I put as a sine qua non condition that the entire cast be Argentine or South American. I want to have that feeling of sharing this with my people. To sing with Europeans, I stay in Europe. Clarin: Are you aware of what is happening in the Colón? José Cura: Not that much. I found out from Clarin that Renán resigned, which worries me a lot, since I respect and esteem him. I was with him a few years ago in Milan and we sealed my performance for next year. His departure is worrying because I fear falling into the hands of those who put up obstacles. Now I want to succeed in Argentina, but not only to gather applause. Sometimes I think that in Argentina we try to carry forward the adage no one is a prophet in his land until his last achievements. I say this from experience. Clarin: What happened? José Cura: In 1983 they rejected me at the Instituto del Colón, and in 1990 they told me that maybe they would give me a piece of paper. Clarin: You once said that opera is not believable. José Cura: If one goes to its essence, it is not believable. There is an insurmountable limit, many things that are said while singing. But look at Wozzeck, so real and plausible, a very realistic love and death story ... It’s the same with characters like Cavaradossi (Tosca). I recommend that you see my Otello live. Someone in England said that I owe more to Orson Welles than to Mario del Monaco in that work. Clarin: Who is your favorite tenor? José Cura: Ramón Vinay, the Chilean, an odd Otello, an exceptional actor ... Clarin: What do you think of opera on film and TV? José Cura: It serves to spread the art, but I am only interested if they act realistically and not if they are on a stage. Clarin: Do your records sell well? José Cura: My Puccini album sold 35,000 copies in Great Britain, against only a thousand in Buenos Aires. And Anhelo has already made it to the top spot at Tower in Piccadilly Circus. From now on, who knows? I believe I have a historical obligation to show the music of my country. There were some who were concerned about the results before the album was released. I told the producers that if it did not sell well they could charge the cost to my bank account.

|

|

|

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive. Cura Fulfilled his Mission Clarin Armando M Rapallo 20 April 1999

[Excerpt] Verdi’s Otello’s was the first protagonist that the Argentine tenor performed at the Colón. Chilean soprano Verónica Villarroel was a revelation. Remarkable staging of the Italian Metresor. With a show of unquestionable interest, the Teatro Colón continues to retake, despite the extra-artistic conflicts suffered in recent times, the high level that led it to the worldwide prestige that it enjoyed for many years. The first performance of Giuseppe Verdi’s Otello, one of the principle works in the international opera repertoire, had various attractions, from the debut in a leading role of the rising Rosario tenor José Cura to the presence of the Italian régisseur Beni Montreso. From the beginning, José Cura exhibited a relevant acting presence, recreating the role of the Moor of Venice with great intensity. He emphasized, musically, his refined vocal technique and a plausible tendency to refine the most intimate moments of his part. Cura achieved his mission, without a doubt, although the sense of being in the presence of a voice of relative volume remains. It can be said that the Argentine tenor sings well and acts better. His was not a brilliant demonstration, although convincing in many respects, as in the death of Otello, Niun mi temo, in particular. [...] The resolution of the final act was masterful. The intimate setting created around the bridal bed allowed Cura and Villarroel to shine dramatically in the harrowing final sequence of the work.

|

|

|

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.

"When everyone speaks well of me, I will retire"

Clarins Maria Iribarren 17 April 1999

He is 36 years old, he lives in France, he is from Rosario and tomorrow he will debut with Otello. In this interview he talks about his conflictive relationship with the Colón, the divo-ism of the tenors, his principles and ambitions.

A biographical synthesis of José Cura should mention that the tenor, who will star as Otello at the Colón (with whom he has maintained a fractious relationship that includes two frustrated presentations—in 1996 and 1997—although they now seem to have found a friendlier course), was born in Rosario in 1962. There he studied guitar, composition and piano and entered the University School of Art. In 1984 he joined the Instituto Superior del Teatro Colón and took singing classes with Horacio Amaudi.

In 1991 he left for Italy with Silvia, his wife, and their first child, José Ben ("in Arabic it means son of, like Ben Hur"). He was one of the winners of the 1994 edition of Operalia (the award sponsored by Plácido Domingo). The interpretation of more than thirty operatic roles is the foundation on which he built his international reputation. Puccini Arias (conducted by Plácido) and Anhelo (sung, orchestrated and conducted by Cura—accompanied by Eduardo Delgado and Ernesto Bitetti from Rosario)—are his first two solo CDs.

It should also be noted that, at 36, the man carries a muscular physique worthy of an athlete. And that he prefers to wear jeans and sneakers, and with his Contax camera in tow, goes out and hunt pictures. "I have the flaw of being a photographer in my free time," he says. "My photos are all those in which I do not go out," he clarifies as he surprises the Clarín photographer in the middle of work. Among other projects to be completed are, precisely, two photo books. One, a kind of traveler's story in images, gathers the curiosities that Cura captures on his tours. The other is a study of "behind the scenes" (of a show, of an interview), that remain invisible to the public's eyes.

Clarins: At last you will debut as a protagonist in Colón. Has your time for revenge arrived?

José Cura: First of all I tell you: no one is a prophet in his own land. I did not write it. It has been in the Bible for thousands of years. I would be a fool if I thought that what happened here is an operation against Cura. Cura 1, Argentina 2—it’s stupid ... After traveling around the world I have come to the conclusion that beans are cooked everywhere. As I am neither the first nor the last, I can’t take this in the first person or feel like the avenger who comes to cut off heads. It's no use to anyone! As an important person internationally, I would like to be able to build the bridge exactly where it once broke so that others can pass through without falling off the cliff.

Today, José Cura and his family (now joined by Jazmín and Nicolás, the younger Curas) live around the Palace of Versailles in France. And if it is true (as his teachers point out) that "the boy was bored" in the audio-perception classes, now the boy seems to savor the size of a giant Buenos Aires audience that will greet him tomorrow.

Clarins: Opera singers are associated with eccentricity and divo-ism. Do you agree?

José Cura: The same thing happens in all human activities: the more mediocre the individual is, the more capricious he is. The less technically prepared he is, the more divo-ist display he offers. The truly greats are quiet people. Obviously the world of entertainment is a showcase, but look what happens with politicians: the less they have to say, the louder they scream; the fewer good ideas they have, the better they dress and comb their hair.

Clarins: With constant exposure, the press will speaks well of you ...

José Cura: Not always, luckily. The day all the press speaks well of me, I retire. Because when everyone speaks well it means that you have lost originality. An artist who breaks the rules fucks up. And I'm breaking them. When you screw up, automatically, you divide the waters: on one side are those who speak well, on the other those who speak badly. But the day everyone agrees, it is because you no longer revolutionize anything. That day you have to be scared. From there, you are out of the story.

Clarins: Where does your innovative horizon go?

Nobody knows that horizon. Because the guy who invented the wheel never imagined that his invention would take us to the moon ...That is too abstract. I'm a fuckup, what do you want me to do?

Clarins: Let's try it again. What would be the limit of that desire to break up?

José Cura: I'm trying different things. In a concert I conduct, in another sing ... In the last one I did in the Vatican I played the piano, conducted, sang, tapped, spoke with the public, gave a sermon to the cardinals ... I was almost excommunicated! They were very happy and the cardinals thanked heaven because no one had ever done a concert with that dynamic in a church in Rome.

Clarins: If they asked you for a song for the end of a soap opera, for example, would you accept?

José Cura: I am of the idea that everything is acceptable as long as you don't have make concessions in quality. The great mistake of the popularization of art is not that it is popular, on the contrary, but that it is bastardized to reach the people. What Mozart wrote is written and there it remained. Bastardizing art is an insult to people. As for what you ask me, if I sing the song well and it is beautiful and the orchestral arrangement is good, I will do it.

Clarins: What if the work is bad?

José Cura: If boys are killed, I won’t do it. But if he talks about love, even if it's kischt, I don't care. My limit is quality. I have invitations every day to sing Wagner. And I reject them because I am not yet ready to sing in German. I do only what I know how to do well.

Clarins: You are going to conduct at the Royal Festival Hall in London, you open the 1999/2000 season of the Metropolitan Opera in New York, Madrid and Palermo, and then?

José Cura: Until 2004 there are many things. But a couple of months ago my eyes were opened ... on December 31, 1999 I should have been the main artist of the end of the millennium celebrations at the Greenwich Meridian, with the London Symphony and guest artists such as Paul McCartney and Elton John. I was going to conduct, sing, accompany, do some arrangements and I wanted to prepare a version of Yesterday and invite Paul to sing it. Suddenly I said to myself: "I can't get to the new millennium lost in Greenwich, freezing to death, in the rain, even if it's on the BBC screens for the whole planet. It seems to me that I am making a mistake." I canceled everything and on December 19 I will be in Rosario with my wife and children, with my parents and my mother-in-law, eating barbecue, on legs in the garden. I wish we could organize such a party like this in Argentina ...

He does not appear to be a man who likes to walk around displaying tears but a good dose of that liquid flooded his gaze more than once during this interview. For example, when he found words to justify his adolescent approach ("I make an effort not to lose it. The day I lose my artistic innocence I change my job. How do you go on stage, dressed as Samson, with long hair around here, thinking you're going to tear down the temple, if you're not an asshole? You can't! "). When he confessed the urgent and necessary closeness of his wife after the stage lights go out and he must readjust to the silence of everyday life. This is José Cura: an Argentine who lives in Paris, a guy who declines all culinary sophistication for a Milanese with fries and a Scottish chocolate ("for the dulce de leche"), and who walks the world testifying that music is the perfect sound system.

|

|

|

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. José Cura uses language with precision and purpose; the computer does not. We offer it only a a general guide to the conversation and the ideas exchanged but the following should not be considered definitive.

"I Am Not a Superman" Opera Actual Luis G Iberni April 1999 Some have wanted to see in José Cura the replacement of the superstar tenors. What is undeniable is that the Argentinean tenor is part of a new generation preparing to inherit divo-ism. Although in Spain Cura is only known by the few who are in contact with the international operatic circuit, this winner of Operalia is one of the artists who has raised the greatest interest in recent times. With a measured career in which he gives up more dates than he accepts and focuses on the dangerous tenor repertoire between spinto and dramatic, Cura talks in this exclusive interview for OPERA ACTUAL about his reality as an artist and as a singer, coinciding with his debut as Otello at the Colón in Buenos Aires and with the appearance of his disc Samson et Dalila. Opera Actual: Although you have numerous admirers around the world, your name is hardly known in Spain. José Cura: That will be fixed very soon, since next October I will debut at the Teatro Real with a new production of Otello. I know that the Madrilenian audience is one of the most demanding right now and for that reason I hope that too many expectations are not raised, since I am not a superman. To introduce myself to those who don’t know me, I am 36 years old and have 24 years of experience in the musical world. I studied guitar, composition, and choral and orchestral conducting. Professional singing came later. OA: With such intense training, your approach to the opera will be different from other singers... JC: Undoubtedly. I have a great advantage, because it gives me the possibility to face the repertoire with a broader perspective and I can make a more thorough analysis of the score as a whole. Actually, my professional aspiration was going this way. But my teacher told me that it would be useful to know the technique of singing for working with interpreters. I started and here I am. Everything is indispensable and nothing is. A career is like a war; it depends on the weapons you use and the way you focus your resources. The physical in a tenor can be positive and negative at the same time. It depends on what kind of roles you face and what approach you give them. OA: What is striking is that you have focused your repertoire on the toughest roles, which are usually considered at the end of a career. JC: The problem in my case comes from the fact that my introduction to opera arrived later than usual. I am 36 years old. I find myself with an unusual physical maturity in an artist with a normal career. But I would dare to say that my evolution has been ideal. I understand that I can now tackle Otello without the risks it represents for a 20 year old singer. You have to think that a role with these characteristics implies more problems than purely vocal ones, as long as you have the necessary physical conditions. OA: What do you mean? JC: The problem with the characters like Otello and Samson is produced by not knowing how you have to manage the energies to get to the end of the opera, controlling what you have to give of yourself on stage. For the recording, the voice above all has to come out. That’s fundamental. But on stage it is essential to exercise control so what happens to many does not happen to you—you don’t burn out after the first act. The dosage of energy is, in these cases, more important than the voice itself. OA: But you do recognize that these roles are very risky. Do you not feel that you are moving too quickly? JC: I will answer with a simile. It is always said that a certain amount of cohabitation is desirable before marriage. But if one day the woman of your life appears and you are aware of it, don't you marry her immediately? Or do you prefer to tell her "wait five years for me to get used to the idea." Most likely, she won't look at your face again. In my personal situation, with a very intense musical experience, things are very clear to me. I've done everything, even sweeping the stage. Twenty-four years of patience and hard work. I think I know where I’m going without wanting to give a feeling of impatience. OA: In any case, your rise in popularity has been rapid. JC: It is the advantage of some contests. But almost every artist with a professional solidity finds a moment when he transforms into a public figure. Opera, however, does not facilitate phenomena like the Spice Girls, with all my respect for the genre they practice. How many years of study did Montserrat Caballe have before she substituted for Marilyn Horne? Many. However, it was only from that moment that she entered the eye of the storm of fame. Popularity comes from a certain point, where it seems that you are suddenly born, without anyone nodding to the professional burden you carry. OA: Are competitions and auditions the only vehicles to get into the circuit? JC: Of course no one knocks on your door by chance. I know quite a few frustrated musicians, full of resentment because they think they deserve a [better] position and due to many reasons no one discovered them. But they are starting from a dangerous misconception. The bag is very large and no one takes you out if they are not aware you are in it, so it is essential to make noise and move. It is a sign, at least, that you are alive. My theory about this is that even though nothing seems to happen, you never stop making noise until they realize you exist. OA: Is it fair to say your career is the result of Operalia? JC: No. At the end of 1994, when I won the contest, I had been in the business for three years and CD to my credit. But Operalia, with a final broadcast to 70 countries, turns a young artist who lives in a restricted circle into someone well known and in whom many theaters are immediately interested. It is really as if after a long pregnancy you give birth. OA: With you popular impact, through the records, countless Internet pages, and television appearances, it is clear that there is a need for artists with voices. JC: Although many people say that there are no artists, that there are no voices, I am of the opinion that this is not true. At a time when the population has increased and we have a greater number of singing students, there is no justification for saying that there are no voices. I rather think that we are facing a lack of singers with charisma. Vocal charisma is what allows someone to stand out, that hides your technical imperfections. In my opinion, that is what is missing. OA: Why is that? JC: Perhaps, to begin with, things are too easy today. It used to take time. Now almost all problems can be solved with a button. But I think that the lack, more than anything, is the product of a social phenomenon. If we do a market analysis, we will see that most of the young artists of greatest importance come from the Third World: Argentina, Chile, Mexico, South Africa or Korea. There, to stand out, you need enormous willpower because everything is, in the socio-artistic sphere, much more difficult. Comparatively, here in Europe the technical means are greater, and that makes personalities develop less, because everything in the First World is too easy. Just look at the invasion of singers from the former Soviet Union. Many are good because they have grown and endured against all odds. I do not want to be misunderstood, but perhaps it is an attempt to explain something difficult to understand. OA: There is no doubt that today's singers have a greater sensitivity both with regard to dramatic and stylistic problems. How do you deal with the latter? JC: I see this more relative; I understand that you have to be respectful of style, but not at the cost of making yourself sick. Any interpretation requires an objective analysis of the work. But above all I think the message matters, understanding that it is the result of a social and artistic reality. I am in love with Bach because I believe that his music is an authentic prophecy to the point that, after him, I believe almost say that nothing new has come. Even Schonberg's twelve-tone is a game compared to some of Bach's works. Taking that into account, do you think that if Bach had the options offered by today's orchestras and choirs, he would repeat the St John Passion with twelve performers? He did what he did because he did not have more possibilities, but that does not mean that we face only a single option. I believe that the role of the interpreter comes from figuring out the artistic prophecy behind each masterpiece, to render our service, ensuring that these tendencies, the result of a certain snobbery, affect us as little as possible.

|

|

Local Hero: José Cura

Classic FM

|

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.

A Return Following Bumps GaceNet/TEMA April 1999

Rosario's tenor José Cura will make his debut in Argentina as the protagonist in Otello at the Teatro Colón. The singer is recognized in the international artistic environment Buenos Aires. "I left Argentina beaten because, as the Bible says: 'no one is a prophet in their land.' But now I return with the bumps healed and with no intention of returning the blows I received," said the excellent Rosario tenor José Cura, internationally recognized but almost ignored in Argentina, who will make his debut as the protagonist in Otello at the Teatro Colón. The singer, composer and conductor, born on December 5, 1962, settled in Europe in 1991 and built a solid career in opera without going through the Colón. José Cura considered that he reached the national stage "at the right time" because "three years ago it might have been premature and two years ago I didn’t have the appropriate repertoire." He also emphasized his own style that places him more as an actor who sings rather than as a singer who acts. "I never understood why to be dramatic you have to shout and why to be romantic you have to sing softly," he said. Cura adhered to the theory of good music without distinction of genres or origins and advanced: "it is possible that you will hear me singing symphonic versions of great boleros. Twenty-five years after the Malvinas war, I want to present live a requiem mass that I wrote and that I intentionally composed for two choirs, as if to be performed by an Argentine and a British choir," he concluded.

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.

An Old Habit Broken Clarins 20 April 1999 There are rites and rituals, customs and diverse uses. What was missing during the evening’s performance was the appearance of the performers at the end of each of the first three acts of Otello, as if there was a conspiracy to ignore the traditional applause, of which much more was expected than the eventual—and unjust—booing from an audience that has never spared its support to the artists who cross its stage. An authority from inside the theater insinuated, without confirming, that it had been José Cura who was responsible for the lack of audience acknowledgement, although the application of the custom, as old as the theater itself, is generally attributed to the stage director. At the end of the opera it was precisely that régisseur, Beni Montresor, who refused to come out, as if there had been some internal disagreement involving the director in this at least curious episode. One more thing: in the last 50 years, no one remembers a similar slight, made more peculiar if you consider that all artists love audience recognition.

|

Otello - Barbican / 1999

Concert Presentation

|

Stunning Simplicity Telegraph Rupert Christiansen 19 May 1999 SOMETIMES I wonder why opera bothers with stage production. For this enthralling concert performance of Verdi's Otello, the soloists simply lined up in front of the orchestra, wearing a variety of evening dress. For the most part, they faced the audience; occasionally they read from their scores. No sets, no lighting, no curtain-up. But not for a moment did you doubt anyone's intense involvement in their characters, and rarely in a theatre have I felt the drama's emotional essence as powerfully communicated as it was here. Opera singers act so much better when they haven't been fed a lot of half-baked notions by pretentious directors and are allowed to let their interpretations infuse through the music and text unobstructed. Interest at the Barbican focused on the Argentinian José Cura, taking the title role for the first time in London. He impressed me greatly. Although those of us with memories of Domingo and Vickers may miss the former's eloquent legato or the latter's howling anguish, Cura's young, bold and handsome Otello made its own mark. His strong, dark, steady tenor lacks colour, but he uses it with musicality and intelligence. There was no recourse to bellowing, and the quiet intensity of Dio mi potevi and Niun mi tema was drawn with real sensibility. He should stop burying his head in his hands to convey despair: more of the finer, deeper points will come with experience. Cura was fortunate in the cast that framed him. Carlos Alvarez made an impeccably crisp and urbane Iago, more top-hatted gentleman than disgruntled Sergeant-Major, and the pretty Bulgarian soprano Andrea Dankova was an ardent and vocally confident Desdemona - star potential here, I think. Among the smaller roles only the British tenor John Daszak disappointed, with a tired-sounding Cassio. The London Symphony Chorus would have matched La Scala's in their stunning attack on the opening storm and the Act III ensemble. Sir Colin Davis conducted. I had forgotten how fast he takes the piece. Detail is occasionally masked, but the dialogues never meander, the temperature never drops, and the climaxes were scorching. The LSO seemed invigorated by his demands and played superbly.

|

|

|

|

Otello

Metro Live Warwick Thomson May 1999

José Cura’s concert performance of Otello, continuing tonight and Sunday, must be one of the most passionate and focused pieces of music/drama in London at the moment. He has a voice teetering on the verge of breathtaking greatness and a mesmerizing stage presence. He used to be a rugby prop forward and semi-pro athlete and carefully places his gestures so that the overall impression is one of immense power. Yet he is also capable of exquisite tenederness00the love duet with Desdemona is ravishingly delicate. His use of South American ‘son’ techniques—the kind of plaintive singing heard in tango music—will offend purists, no doubt; but the incorporation of these lilting, sobbing sounds into this Italian opera convey a powerful sense of Otello’s cultural difference. The London Symphony Orchestra under Sir Colin Davis played superbly on Monday but occasionally overwhelmed Cura: mere horsepower, however, is something he will undoubtedly gain with age. Greatness is already his.

|

|

A Commanding Otello The Guardian James Naughtie May 1999 The problem with being an international tenor of promising stature at this moment is that the dreadful question is asked everywhere: “Is this the fourth?” But José Cura, the relatively young Argentinian singer, wears that millstone reasonably lightly. His may not be a voice for the Millennium, and it may not prove to be one that lasts for a generation, but it is a formidable instrument. In his concert performances in the title role of Verdi’s Otello in London last week with Sir Colin Davis and the London Symphony Orchestra he was spared the harsh light which staging would have cost on his thespian abilities, and his voice shone. With the promising soprano, Andrea Denkova, beside him and an extremely vigorous sounding Carlos Alvarez as Iago, he turned in performance of real style. This is a part, of course, which became the property of Placido Domingo in the Eighties. Cura has none of that burnished depth to his voice yet, though its silkiness showed there is much more richness to come, and he does not yet have the command across his range that the role requires when it is being performed against such majestic forces as the LSO mustered at the Barbican. But it was good, maybe very good, indeed. Cura is showing unfortunate signs of being diverted into silliness, as the effort to conduct and sing at his own gala earlier this year demonstrated. Everyone should hope that the myriad temptations down this road are resisted. He sings well. He seems to feel Verdi in him and we should hope that the new Covent Garden has him well placed in its roster. Once again, Colin Davis demonstrated his undiminished boyish enthusiasm for scores like this, leading his orchestra with punch and verve from the first crashing sounds of the waves on the Cypriot shore. With Cura’s opening “Esultate!” ringing out in promising fashion, it was clear that this was a performance, and a performer, which would rise well above the ordinary. The question now is whether it is a performer who will grow. If he does, we will all come to know him well. If not, the tragedy is he will be described as another fourth tenor who never was. He deserves much better.

|

|

Insult to Verdi The Times Rodney Milnes 19 May 1999 It’s time to start debating precisely what a concert performance should be, and whatever answer is reached, it will not be what happened at the LSO’s performance of Otello on Monday. Despite a handful or excellent individual performances, much exciting orchestral playing—though the LSO’s somewhat aggressive ‘brightness” of sound can grow a little wearing—and Colin Davis at his most genial really sculpting the long-breathed tunes and discreetly urging the dram on, this was not in any sense a serious occasion. To act, or not to act, or rather “act”? Some did, others restricted themselves to frowning and looking vaguely thoughtful. The playing area was to the left of the platform, and since the chief “actor” and star of the shoe, José Cura, took centre stage, he frequently turned his back on a large section of the audience. To have scores or not to have scores? Cura did both, but continued to “act” while turning pages. You can’t murder someone in bed on the concert stage and then commit suicide: what happened in the fourth act was simply ludicrous, Desdemona turning her back and drooping, Otello doing some heavy breathing. The worst of both worlds, then, a quarter-cock dramatic version without the advantages of a really carefully prepared musical performance. Cura’s “acting” was restricted to stock tenorial posturing, much beetle-browed smouldering and careful presentation of his famous left profile. Verdi’s Otello? Forget it. The man’s vanity is in danger of making him the laughing stock of the operatic world, and in failing to decide whether to pursue a career as a singer or a sex-object, he is short-changing fans on both counts. Which is a tragic waste. He is prodigiously gifted, and there were moments of imaginative, insightful singing, especially in the third-act Monologue, but they sat check-by-jowl with the sort of brash phrasing better suited to Pagliacci than Otello. So Carlos Alvarez, wh stood, sang Iago’s music with beautifully focused, inky tones and projected Boito’s text with real understanding, walked away with the show with—given a pale, edgy-voiced Desdemona—a little competition for Enkelejda Shkosa’s spunky Emilia. An interval announcement reminded us to go and buy Cura’s CDs from the merchandising point. For heaven’s sake, were we in a concert hall or a supermarket?

|

|

Going Solo: José Cura A Moor for the Millennium M. Pappenheim LSO Living Music 1999

|

|

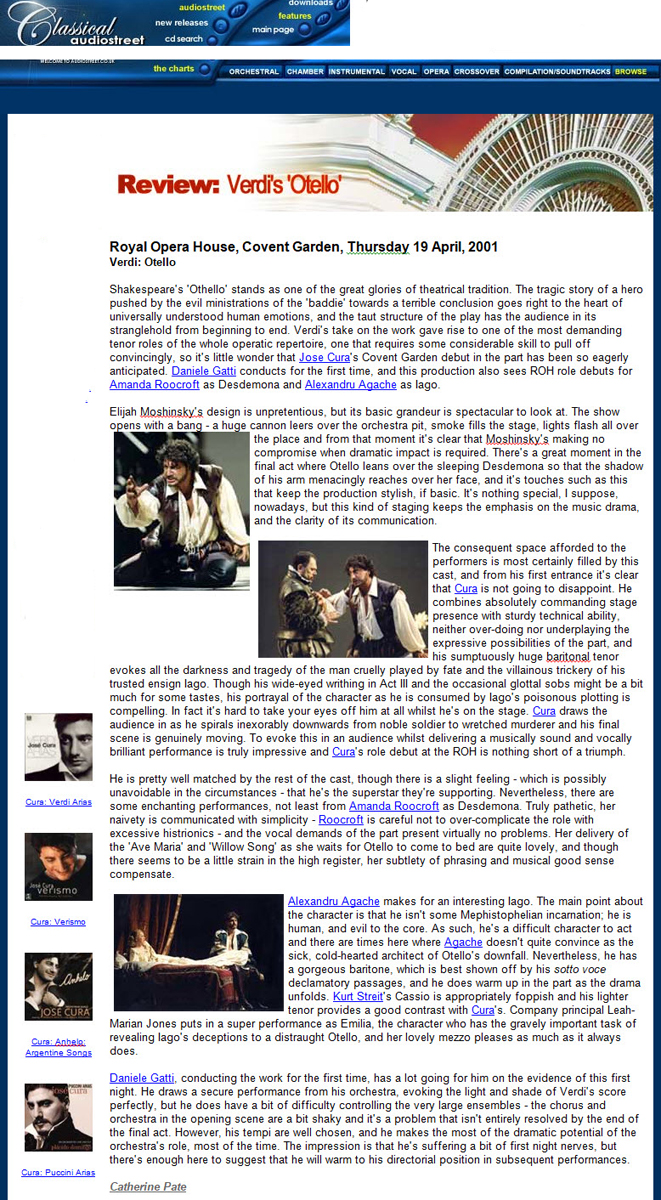

José Cura Opera October 1999 John Allison (excerpts)

|

Otello - Teatro Real / 1999

First staged performance in Spain

|

|

|

|

|

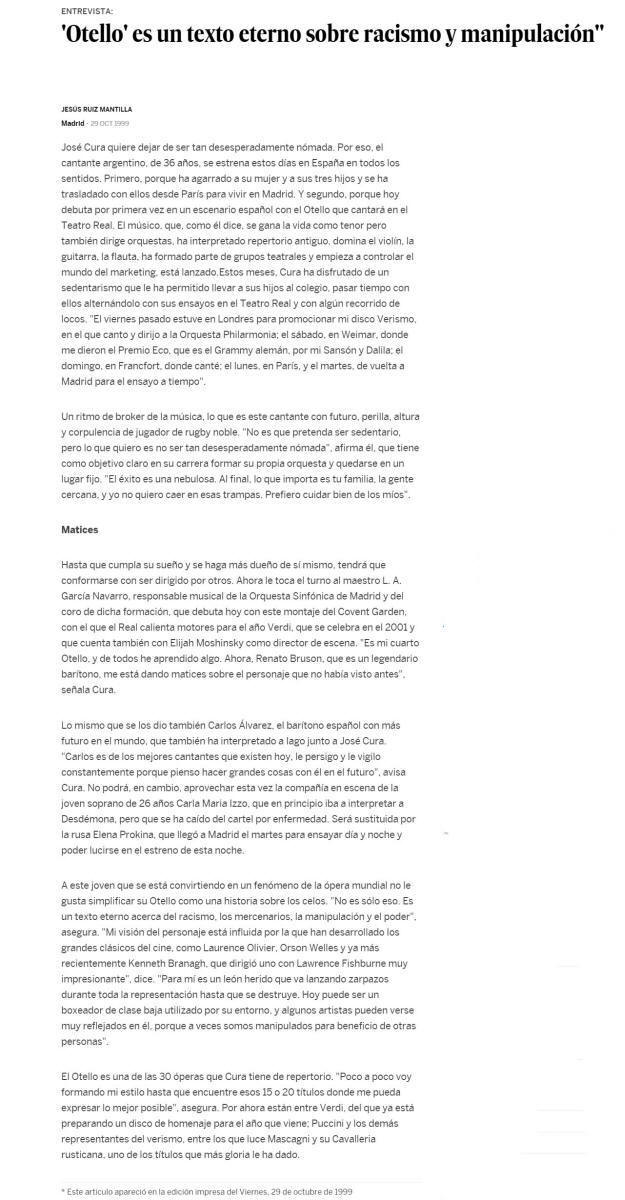

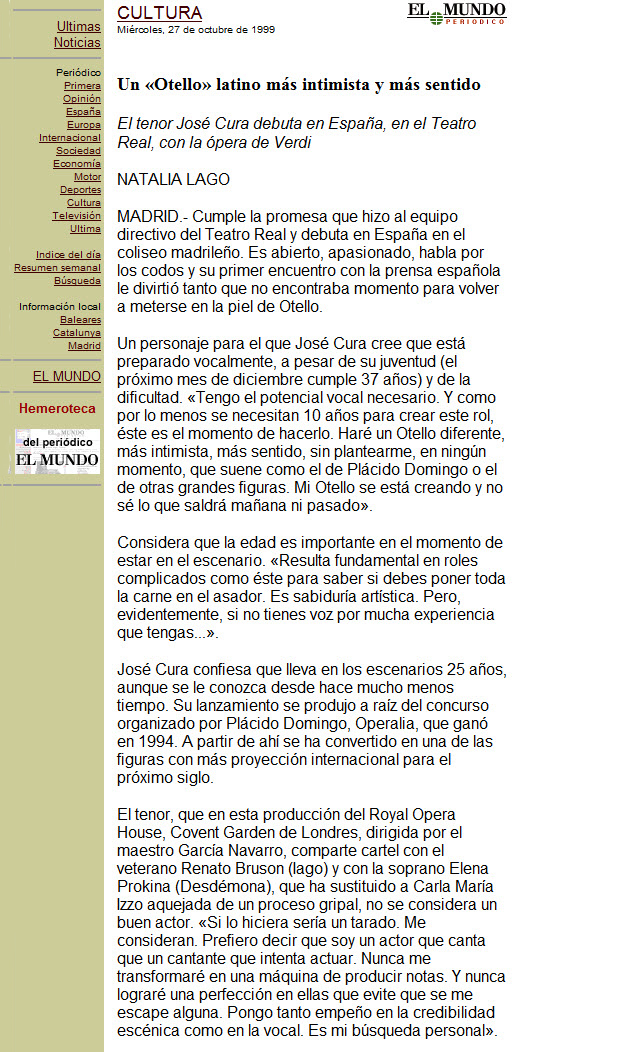

A More Intimate and Heartfelt Latin Otello El Mundo Natalia Lago 27 October 1999

The tenor José Cura makes his debut in Spain, at the Teatro Real, with Verdi's opera MADRID - He is fulfilling his to the management team of the Teatro Real and making his debut in Spain at the Madrid Coliseum. He is open, passionate, talks a lot and his first meeting with the Spanish press amused him so much that he couldn't find the time to get back into Otello's shoes. [Otello is] a character for whom José Cura believes that he is vocally prepared, despite his youth (he turns 37 in December) and the difficulty. “I have the necessary vocal potential. And since it takes at least 10 years to create this role, now is the time to do it. I will make a different Otello, more intimate, more meaningful, without ever thinking that it sounds like Plácido Domingo's or other great figures. My Otello is being created and I don't know what will come out tomorrow or the day after. He considers that age is important at the time of being on stage. “It is fundamental in complicated roles like this one to know if you should put all your meat on the grill. It's artistic wisdom. But, of course, if you don't have a voice, no matter how much experience you have ...” José Cura confesses that he has been on stage for 25 years, although he has been known for much less time. He was launched as a result of the contest organized by Plácido Domingo, Operalia, which he won in 1994. Since then he has become one of the most internationally renowned figures for the next century. The tenor, who in this co-production of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden in London, conducted by Maestro García Navarro, shares the bill with veteran Renato Bruson (Iago) and soprano Elena Prokina (Desdemona), who replaced Carla María Izzo who had to withdraw after developing flu-like symptoms, does not consider himself a good actor. “If I did, I would be a moron. I prefer to say that I am an actor who sings rather than a singer who tries to act. I will never transform myself into a note-producing machine. And I will never achieve a perfection in them that prevents me from missing any. I put as much emphasis on stage credibility as on vocal. It is my personal quest.” Complementing the career Born in Rosario (Argentina) of a Spanish mother and grandfather, he sings, conducts and composes. He is a versatile artist who does not seem to want to waste a minute. For José Cura, this diversification is part of the same career. “It completes it to become an artist of integrity and to keep me alive. You spend your life dreaming. When the time comes and you are asked to make it happen, why would you say no? Some will think that I am presumptuous but these are dreams come true with quality and with a professional background. They are not whims.” What he most wants is to be able to reconcile his professional life with his private life. "When you miss the baptism of one child and the first communion of another, you remember it and cry." Now his dream is to live in Madrid, where he has already signed with the Teatro Real to perform in a production every year. The next ones will be Il trovatore and Cavalleria rusticana. José Cura is not comfortable with the reputation as sex symbol that he has been given because he fears that his physical appearance will eclipse what is truly important: his work. Nevertheless, he admits that he is flattered by it. "It's incredible that they say that when only my wife knows me in private," he explains with a laugh. Then he recovers his seriousness and focuses on his next role, Alfredo in La Traviata, conducted by Zubin Mehta. "But it is clear that it will not sound like we are used to, it will be more believable and never dark." He will begin to prepare it as soon as Friday's premiere at the Real passes and he has finished with his particular struggle: to represent a different Otello, "neither dramatic nor heroic but pathetic."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The production is an adaptation of the one created for Covent Garden in London in 1987 by Elijah Moshinsky, of which little more than the indications of entrances and exits and stage settings remain. Each of the main interpreters has allowed to present their particular vision of the character, especially Otello and Iago. The result is a somewhat washed-out plot, without stylistic unity of interpretation. Thus it was possible to see a hyper-realistic Otello, with spectacular thumps and epileptic seizures; an Iago with a certain mannerism in poses and movements offered in the best melodramatic tradition of the Italian provincial theaters; and a very traditional Desdemona, very classical in gesture and manner, and who moved and acted with the lightness of a ballet dancer. But it is in the direction of the choir and the troupes where this staging of the Teatro Real really fails. As an excuse, the lack of experience of a choir on stage for the first time after its recent creation… There are some odd slip-ups that are surprising from a stage director as experienced as Moshinsky. One very evident: Otello hands his sword to Lodovico before singing Niun mi tema (Let no one fear me even if he sees me still armed); both his words and the stage directions advise waiting for the end of his first stanza with “Otello fu” (Otello I was) before surrendering the sword or simply dropping it. […] García Navarro was received with a few whistles after his return to the pit once the interval was over; part of the audience reacted with applause and a brief scuffle was organized that had its apex when the maestro came out to greet the audience at the end of the performance. Apparently it had been a protest organized by a limited and localized group, although I witnessed some spectators booing on their own. I read in the Madrid newspapers the association of the name of Arturo Toscanini in relation to García Navarro's conducting and others in praise for the style of his lackluster performance. The Madrid Symphony Orchestra sounded bad, tinny. Maestro and orchestra contributed enthusiastically, and whenever they had the opportunity, they filled the pit with thunderous noise that threatened to spoil a performance that both vocally and dramatically had great dignity.

|

||

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.

Otello: Bruson and Cura Captivate the Audience at the Teatro Real Estrella Angel Munoz November 1999

[Excerpt] "I believe that a just man is only a hypocritical buffoon. I believe man a plaything of wicked fate. Heaven is but an old tale." This is how Iago, the villain from Verdi's Otello, expresses himself, masterfully interpreted by the baritone Renato Bruson. His voice and performance is what most captivated the audience in Teatro Real in this Shakespearean tale of jealousy and human manipulation through defamation, one of the most effective tools to destroy lives today and forever. The pairing with José Cura, the Argentine tenor to whom they want to put the stamp of 'successor' of Plácido Domingo, is by far the best aspect of this opera, in which Desdemona, performed by the soprano Elana Prokina is a bit dull, without character, almost in continuous prayer, although with great musicality in her role as a mistreated wife unjustly accused of infidelity. For José Cura and Renato Bruson this is their first time at the Teatro Real. Cura, who intends to make his permanent residence in Spain, had promised this appearance in Madrid to his friend García Navarro. The great tenor has also signed a contract for Il trovatore and it is expected that he will commit himself to the operas Pagliacci, Andrea Chenier and Cavalleria rusticana, the latter title that has spread much of his world fame. As for the review of the first performance—on Friday (opening night) Cura was nervous and somewhat out of tempo at times. By the second, on Tuesday, the nerves turned into security and good work. Cura and Bruson had to go out to say hello between acts because of the excitement of the audience. The jubilation was so great that some loudly criticized the 'excess' of applause at the moment when the director Garcia Navarro greeted the audience at the beginning of Act III. The artistic and musical director of the Madrid opera temple seems to have some bitter enemies among a small part of the public.

|

Otello - Teatro Massimo / 1999

Palermo

|

|

Otello - The Washington Opera / 2000

Washington, DC

(Now the Washington National Opera)

|

|

|

First Opera Ever |

|

|

First Otello |

|

|

|

First Meeting with José Cura |

|

The Two Fine Voices Of Otello

By Philip Kennicott [Excerpt] The popular Argentine tenor Jose Cura sang Verdi's Otello on Wednesday night with the man who has defined the role for a quarter-century staring him down from the orchestra pit. Placido Domingo, one of the greatest Otellos of the century, was conducting the work for the first time at the Kennedy Center Opera House. Cura, onstage, was doing the equivalent of playing Hamlet for Sir Laurence Olivier. The Washington Opera production, which is steadfastly traditional, was enlivened by the drama of watching a torch being passed. No artist should be heard only in comparison to another. Cura has wisely decided to stand aside from Domingo's long shadow. Domingo returned Verdi's Otello to its precedent and inspiration, Shakespeare's Othello, concentrating on the title character's almost abstract progression through the stages of doubt, jealousy and rage. It was the slow dismantling of a statue, from the opening clarion call of "Esultate!" to the final, unfinished whisper, asking for one more kiss . . . "un altro bacia . . ." Cura takes the role more within the tradition of Italian opera than Shakespeare. On Wednesday, in a production that offers little new, but is technically solid, Cura's Otello was smaller and more given to thoughts of victimhood. One sensed more the pain of a vanishing dream, the sadness of disillusionment, than anger at the destructiveness of Iago. At the moment, in the text, when anger finally wins, Cura's cries for blood--"Sangue! Sangue!"--came from some other place, not rage, not certainty. Cura's warm but lyrically lighter voice sets natural limits to the heroism of his Otello. He compensates by going further into the more tender dimensions of the role. In the tradition of Italian opera, we expect the tenor's death to be touching, and Cura made it so. But in the tradition of Shakespeare, we expect it to be horrifying, and Cura evaded that dimension. His Otello wants to be loved. There was enough to like. Cura's voice is attractive and, within its natural compass, effortless and easily produced. He is a musical singer, with a natural sense of phrasing and a tenor's instinct for the drooping, sighing, clinging line. He is more self-consciously an actor than many opera singers, an actor aware of his own glamour and the possibilities it creates for connection to an audience that wants and needs stars. The new production of "Otello," directed by Sonja Frisell, did not arrive without bumps in the road. The originally scheduled soprano, Daniela Dessi, pulled out on short notice, forcing the company to scramble. It found a replacement in the Chilean soprano Veronica Villarroel, who had only three rehearsals but, with the aid of a prompter, sang with confidence. Villarroel, who has sung the role of Desdemona only once before (with Cura), has blossomed into a singer who can ramble about comfortably in the large Verdian repertory. Her voice suggests a certain thinness of texture, but is more than ample to be clear and vibrant in large ensembles. In the last act, she sang at a very fine level, sensibly and sensitively. In earlier acts, she seemed a happy exception to this sometimes sedate production; Villarroel was the uncontrollable element, the only singer working in the realm of pure Verdi mania, musically volatile and threatening. Supporting the hero and his maligned wife were the Iago of baritone Justino Diaz and Iago's wife, Emilia, beautifully sung by Elizabeth Bishop. Diaz is a barker and his Credo, opera's greatest glimpse at pure evil cast in musical garb, was a disappointment. Domingo, who is building a new career as a conductor, has recognizable, interesting and compelling thoughts about a score he knows extraordinarily well, but the technique is not solid. There were stray players here and there (once, unfortunately, in the finale to Act 3), and passages, especially with chorus in Act 1, when the rhythmic foundation was slippery.

|

|

José Cura: The next superstar tenor?

Globe And Mail Philip Anson 13 March 2000 [Excerpt] Washington Opera at Kennedy Center in Washington In the current frenzy to replace the Three Tenors, one of the top contenders is José Cura. The 37-year-old Cura has made his mark singing some of the toughest tenor roles in the world's best opera houses. His voice is medium-large, baritonal and very expressive. As an actor, his sweaty intensity is a throwback to the scenery-chewing Italian singers of the fifties and sixties. Any of these qualities would place Cura ahead of most wannabe tenors, but the swarthy hunk has another trump card -- he actually looks like the irresistible seducers and fatalistic heroes that he plays. A former bodybuilder and karate black belt, Cura is pumped, agile and frankly sexy. Not since the heyday of the svelte Italian Franco Corelli has a tenor worn such tight outfits with so much impunity. So it is not surprising that Cura is the star of the current Washington Opera production of Verdi's Otello. Verdi's operatic treatment of Shakespeare's jealous Moor is a magnificent collage of primal emotions played out under the hot Mediterranean sun. Otello has some of the finest introspective monologues, mad scenes and lyrical love duets ever written for male voice. But the stretch from heldentenor stamina to lyrical finesse also makes it one of the most difficult roles in the tenor repertoire. To his credit, Cura has the stamina, the acting ability and the voice to meet these challenges. His Otello is multidimensional -- both a heartbroken wimp and a maniac. When Desdemona betrays him, he writhes like a crushed worm. But when he glares at his enemies, bellowing and spitting, you can almost smell the gamey aroma of a gladiatorial arena. As the wronged wife Desdemona, soprano Veronica Villaroel matched Cura's presence, while outdoing him in vocal professionalism. Despite her rather peculiar diction, Villaroel is a diva in the grand tradition, with powerful projection and excellent technique. Like Cura, she brings fiery Latin temperament to her roles. The murder scene on Desdemona's bed was dangerously sexual as Cura mounted Villaroel and closed his hands around her neck, closing a thrilling night of Grand Guignol. The only weak link in the cast was the Iago of veteran Puerto Rican baritone Justino Diaz, who was shockingly miscast. Diaz is nearly 60 and sounds like it -- he spoke rather than sang in a faded and utterly innocuous voice, a far cry from the devil's spawn Verdi imagined. The Washington Opera Chorus was loud and hearty. The Kennedy Center Opera House Orchestra, a pickup band with members of the National Symphony, played vigorously and with surprising panache under conductor Placido Domingo. The 1992 sets and costumes by Zack Brown were grand, logical and realistic. Direction by Sonia Frisell, especially of the chorus, was animated, detailed and convincing.

|

|

|

|

[Excerpt] WashOp has a new show in town right now—Verdi’s penultimate masterpiece, Otello, which closes the current opera season—and it’s good. It’s good in its own right, and even better in the context of WashOp’s Verdi-challenged history. It should be noted that the company’s difficulties with this 19th-century icon have rarely centered on singing, which has, more often than not, been quite strong. The problem has been one of creating productions that make this most theater-savvy of Italian opera composers look risibly melodramatic and unredeemably old-fashioned—an old fart worth attention merely because he knew how to write a swell tune. But, like Shakespeare, Verdi could take the dustiest old stories, the most overwrought emotional situations, the least likely relationships, and transform them into works of universality and transcendence and psychological complexity. And when Verdi and the Bard (by way of Arrigo Boito’s literate, sophisticated librettos) came together, the results reached a pinnacle of operatic form. Otello is a melting pot of bel canto lyricism, Wagnerian leitmotif, and Elizabethan poetry. The world it creates is one where private lives are publicly exposed and public lives are destroyed with a word. Verdi was writing at inspirational white heat here, and his grand opera rhetoric is as eloquent as his quietest, inward-looking arias. The current revival of that infamous production doesn’t begin auspiciously. Cheesy strobe-lightning flashes make all the faux granite in Zack Brown’s set look even more plastic than it is, and the chorus, for all its enthusiastic gnashing of teeth, looks silly under the low-rent meteorology. But as the soloists start getting to work, director Sonja Frisell’s staging takes on some compelling life. Key to the production’s success is young Argentine tenor superstar José Cura. Cura’s under an unusual level of scrutiny here. This revival, after all, was to have been D.C.’s chance to experience Domingo’s near-definitive Otello in the flesh at long last. So when it became clear that WashOp would remount the opera, but Domingo (who just sang it last fall at the Met) would be retiring the role of Otello moments before our local production opened—choosing instead to conduct the revival—it all seemed like some mean-spirited joke. Casting the young Cura in a role most tenors wait their entire careers before tackling was a controversial move. But youth has its advantages. Cura’s got runway-model looks, which he exploits in a series of smoldering poses straight out of the International Male catalogue. He’s also got that Latin thing going, which worked well for Domingo and Carreras early in their careers, and never hurts in the leading-man sweepstakes. And you can practically count the number of hours he spends each week at the gym, thanks to what must be the tightest costumes ever worn by an opera singer. (My girlfriend managed to take every conversation we had about Cura’s singing and turn it around to the subject of his thighs, which she was evidently mesmerized by.) Cura achieves what most tenors can’t, even with a battery of corsets and hairpieces: heroic credibility. Cura’s acting, despite the element of self-regard in some of his antics, is strikingly effective. This Otello’s affection toward Desdemona looks lived-in and genuine. There are an enveloping tenderness and an erotic charge to their relationship that are rarely communicated so well on the opera stage. As his character starts unraveling, Cura creates a canny mix of crushing disappointment and repressed rage that tips over gradually into psychosis. Physical passion is inextricably bound up here with the potential for annihilating (ultimately self-annihilating) violence, and only a creepy, pretty-boy charm stands between impulse and action. To Cura’s credit, he avoids the standard-issue blackface, using his own swarthy complexion to suggest the Arab, rather than the African, side of Otello’s Moorish heritage. And in a nice bit of Shakespearean accuracy, Cura generates a convincing epileptic seizure at the close of Act 3. Vocally, he’s in much the same form as in WashOp’s Samson et Dalila last season. The dark baritonal timbre is still virile and thrilling, the support sure up and down the wide compass of the role. It’s an instrument capable of conveying dramatic change with great immediacy. If there are any surprises this time around, it’s the way Cura comes off the high notes fairly quickly. Nothing in the sound or production of those notes is strained or awkward—quite the contrary—which suggests that he’s trying to conserve the voice, not just through each performance, but for the long haul. (Otello, after all, is a notorious voice-wrecker.) Cura is like a panther who’s placed in successively smaller cages as the story progresses… Cura’s Desdemona, Veronica Villarroel, is the real goods. She’s a genuine Verdi spinto with a middle register like warm caramel, a melancholy cast to the sound that’s tailor-made for tragic heroines, and the ability to float ethereal high notes. Villarroel’s acting is broad, built from a traditional vocabulary of stances and gestures and glances heavenward. But, to her credit, she makes it all look like second nature, and because she believes it, we pretty much believe it, too, and can be moved. Justino Diaz has been singing Iago for a lot of years now, and his interpretation is an amalgam of naturalistic acting, blank-faced singing, vibrant physicality, stock poses, rote bits of business, verbal subtlety, vocal bluster, and sheer chutzpah. At the opening, he seemed engaged in playing his character only when not singing. His voice was in trouble, with hoarse patches, tired high notes, a lot of uncomfortable sharp singing (no doubt in an effort to avoid even more uncomfortable flat singing), barking attacks, and vocal effects taking the place of a direct response to the text. Director Frisell creates clear-headed stage business for the singers overall while giving her leads in both casts the freedom to incorporate alternate ideas to make these roles their own. Domingo has gotten a lot of flack for his journeyman conducting in the past, but I’ve never encountered a Domingo-conducted performance that went seriously off the rails or lacked imaginative interpretive ideas. Ensemble, though, was intermittently sketchy at both performances. Some tricky numbers, like Iago’s drinking song in Act 1, held together well, but the opera’s opening chorus veered dangerously out of sync with the orchestra.

|

|

|

Otello - Munich / 2000

|

|

|

Otello in Munich Opera News Jeffrey A Leipsic October 2000

June 15 brought a rare opera evening that promised much and delivered more. All three major roles in Verdi’s Otello at the Nationaltheater were cast with singers appearing for the first time with the company. Special interest centered around tenor José Cura in the title role. It must be admitted that the local public has become suspicious about the “publicity machine” mentality of the major record companies, having been bamboozled once too often by glossy yet empty hype. Perhaps for that reason, tickets were available up to the last minute. Besides, Cura had canceled an engagement elsewhere in Europe the week before and, although it was to be his first appearance in Germany, one was not overly optimistic about his turning up at all. Francesca Zambello’s busy production, much maligned during its first run, in July 1999, began well enough. The chorus sounded in good form, and the constant activity seemed less superfluous. Then came Otello’s Esultate, and once could feel the electicity run through the audience, which seemed incredulous as it waited for the love duet before passing judgment. In between, Sergei Leiferkus steered away from over evil as Iago choosing subtle malevolence instead. Lieferkus has never met a pure Italian vowel that he couldn’t turn into a Russian-sounding diphthong, but his voice is large, strong, well centered and full of personality. The ensuing Otello-Desdemona love duet catapulted the performance into another universe. Cura, a stunning figure of a Moor, linked phrases (no breath between “l’ira immensa” and “vien quest’immenso amor!”), soared as the music moved upward and intoned the final “Venere splende” immaculately while lying on his back, his head in Desdemona’s lap. Barbara Frittoli, as Desdemona, matched his every achievement. Her middle register was pure cream, her pianissimos (in “Amen risponda,” for example) were as breathtaking as they were well chosen, and her top notes emerged full and without strain. The evening moved from one superb scene to the next, with Cura gaining in intensity until his passion totally engulfed the audience. He seems willing to sacrifice tonal beauty for dramatic fervency, and eventually that may cost him dearly. For now, his epileptic fit was as credible as his jealous outbursts, and his vocal mastery of the fiendish part was awe –inspiring. Frittoli’s Ave Maria left hardly a dry eye among the audience, and the crushing drama of the death scene even led to a few seconds of silence after the final curtain. […] General music director Zubin Mehta led a fiery reading. He was not always of the same opinion as Cura concerning tempos but, if anything, this added to the unique spontaneity of the evening.

|

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.

Multi-talented and Stage animal Fono Forum Thomas Voigt September 2000

A stroke of luck: José Cura is a tenor, conductor and composer. He has everything needed for a media career and he is one of the very few real theater singers today. With his latest initiative, the TV Traviata, which was broadcast worldwide at the beginning of June and which has now come onto the market as a soundtrack, he was able to reach the huge number of viewers that otherwise would have been impossible today. The fact that he has long belonged to the first ranks was seen shortly afterwards with his performance in Otello at the Bavarian State Opera, his stage debut in Germany. Thomas Voigt spoke to the artist the morning after the performance. Thomas Voigt: Mr. Cura, you sang two Verdi parts that could hardly have been more different within eleven days. First Alfredo in La Traviata, a lyrical, almost "tenore di grazia" part; and now Otello. Normally every conductor and vocal teacher would strongly advise against it. José Cura: I don't think these roles are so far apart. In my opinion, Alfredo is not a tenore di grazia; it was made so by some tenors who wanted to sing this part. Regarding the tessitura and the texture of the music, we have exactly the same thing with Alfredo as with the Manrico in Trovatore. But I wasn't the typical Alfredo, not the traditional Alfredo; I was more of a macho Alfredo (laughs). TV: According to the original, Alfredo is a rather sensitive soul. JC: Yes, but he is a real man, not a sissy. He comes from the province, is introduced to fine Parisian society, and there he attracts the most desirable woman, leads her away. In doing so, he challenges everyone. And should such a man sound anemic and chaste? Or consider Werther (whispers the phrase "Pour quoi me réveiller"): Does it really have to sound like this? After all, the first Werther was a Wagner tenor. In addition, you should be so flexible as a singer and actor that you can do justice to different parts. Caruso sang La fanciulla del west one evening and L'Elisir d'amore the next. But then came this unfortunate drawer thinking, this specialization, with the singers as well as with the doctors. So you don't get me wrong understand this: I have no objection to someone singing parts like Alfredo or Rodolfo very finely and lyrically, but you shouldn't make it a dogma. It should remain open to other types of interpretation that are just as convincing. TV: What if a conductor comes and says: That has to sound more lyrical, soft and sweet? JC: So far I have always had the luck that the conductors who hired me were convinced that I would find my own way to the role. And if we don't agree on one point, then we discuss it. It's a collaboration. We are partners. Good art is always communication, constructive work together on interpretation. That's the way real artists work. TV: Is the time of the despots on the podium over? JC: I think dictatorial behavior has never done art any good, if only because there are always several ways that lead to the goal. Anyone who insists only on his position and dictates it is depriving himself of the right to interpret. Well, there have been some great conductors who were called as despots. But believe me: a really great artist is never an asshole. TV: No exceptions? JC: None! You can't write music like Verdi and have a lousy character at the same time -- impossible! Perhaps Verdi was not very popular with some; I'm convinced that his perhaps somewhat brusque manner was self-protection. At the moment of creative design you have to have a child's soul. But few artists show their child's souls because they are forced to protect themselves. TV: Finding your own way to the role - how does that work when you get into an impressive production? JC: With rehearsals and improvisation. Compared to the premiere, we changed a lot with Otello, especially in the third act. I still find the second act somewhat problematic. As you know, the second half of the second act is the absolute touchstone for every singer of Otello, and of course it is precisely there that I am placed at the back [of the stage] in a deck chair, in the middle of nowhere. Well, I could have gone to the ramp with "Ora per semper," but that is really not the solution. TV: There are several live recordings of your Otello, Buenos Aires, Palermo, Turin and Madrid, all on video. When does the first record recording come? JC: In the fall of next year. With Barbara Frittoli as Desdemona, Carlos Alvarez as Jago and Colin Davis on the podium. TV: Actors often differentiate between "Natural" and "Method." Which do you see yourself as? JC: Natural with Method. If you are just a "method actor," you lack the dimension of the spontaneous - and the animal. And you can’t do it alone with only nature, as many the examples of singers who have had to stop too early because they had no technique. Of course, the first thing you need is the gift of nature, the talent. And then you have to start working with it. Only then is the matter complete. As paradoxical as it sounds, you need technique to hide technique. The audience should never have the impression that you are “doing” something. If you see an actor playing, he's not a good actor. The same applies to the singer. TV: In an interview you said a high note is like an orgasm. JC: Oh, that's always misunderstood. So, by orgasm I don't mean the moment of ejaculation, but the moment of total physical liberation after an enormous tension. Take, for example, Otello's monologue in Act Three: you build up tension for three minutes in order to finally achieve this target "O gioia!"; the subsequent physical release and relaxation is comparable to an orgasm. And the nice thing is on stage you can experience four or five such moments in one evening. TV: What is it about all these stories and anecdotes that tenors have to be pretty celibate to be able to sing properly? JC: You have to find out for yourself what's good for you and what's not. As for me: I eat when I'm hungry. In general, I try to live a normal life without all these precautions. It would be terrible if I don't dare to go to the museum because as a singer I'm afraid of the air conditioning. How can you sing certain music if you haven't seen the corresponding artwork? TV: People often complain that there are hardly any great personalities left in the opera world. When asked about this, Christa Ludwig said that this was only logical, because in today's world a great personality would only disrupt. What is needed is an appropriate mediocrity that ensures the smooth functioning of the company. JC: A very intelligent comment. The bigger and stronger you are, the more the smaller and weaker ones will feel threatened and work against you. It has always been that way and it will always remain so. These conflicts do not exist when there is a balance of powers, however: when there is no envy and no feelings of inferiority, then the forces work together. For example, yesterday Barbara Frittoli was Desdemona. Singing next to such an artist is inspiring and motivating: you reach another level. TV: If you could change something essential in the Music business - what would it be? JC: The mindset of those who think that classical music is something elitist. It should have the same value in life that it had when Puccini arias were whistled by everyone in the street. This separation of classical and pop music is an invention of the 20th century. We have to say goodbye to that. Then we would not need this so-called "cross-over" - a word I hate. For me, "cross-over" means: "We are here and have our fine art; and on the other side of the river are all the poor sausages who don't know what true art is and whom we visit every now and then. But thank God, we can go back, we can keep to ourselves." Unfortunately, you can also find this elitist attitude in the media. You know that the television production of Traviata has been attacked by some critics. Why? Because we had dared to spread jewels of opera art among the people. This attitude is totally arrogant! For me there is only good and bad music. I’m a great fan of Barbra Streisand. Why shouldn't I be as moved by her music as by a Verdi opera? After all, that's the point of every art: to be touched and moved.

|

Otello - Vienna Staatsoper / 2001

|

|

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.