Bravo Cura

Celebrating José Cura--Singer, Conductor, Director

Operas: Pagliacci

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

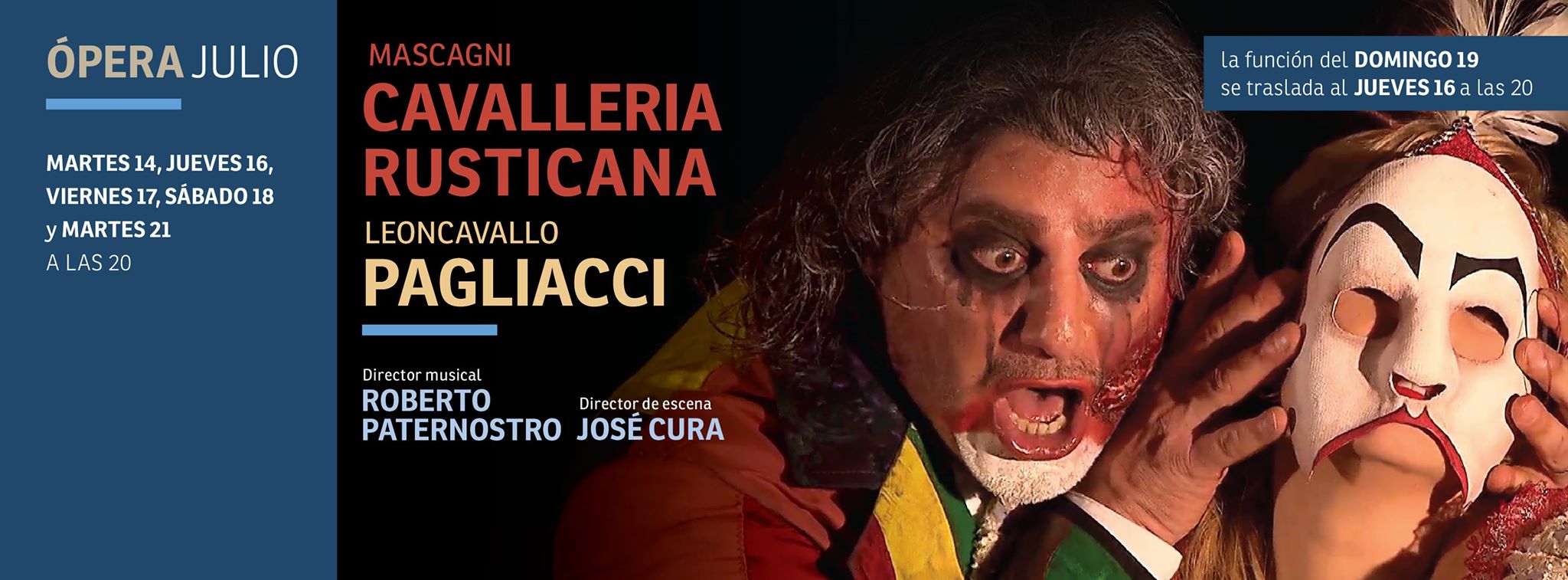

José CuraDe regreso al Teatro ColónEl tenor argentino vuelve al país para presentar Cavalleria rusticana y Pagliacci. Vive en Europa y considera que la crisis es mundial y no económica, sino moral.

—¿Cómo describiría al Teatro Colón en este momento? —Aunque yo soy argentino, y el teatro es mi primera casa, no dejo de llegar como un invitado. Veo cambios, veo esfuerzos. Y más allá de los inconvenientes que pueda tener un teatro tan monstruosamente grande como es el Teatro Colón, el factor humano es el que siempre hace que salgan las cosas adelante. La gente del Colón quiere mucho al teatro, quiere mucho su trabajo, y son artistas de raza, hasta los maquinistas. Con respecto al 2013, siento que hay un poco más de serenidad. Además, han ajustado y actualizado los sueldos, lo cual le hace muy bien psicológicamente a todo el mundo. —¿Qué reflexión le merece que un espectáculo como el que usted presenta realice sólo cinco funciones? —Un teatro con la máquina que tiene el Colón tendría que hacer muchas más funciones al año. Esto no tiene que ver con una voluntad de no hacer, sino con el presupuesto. Para óperas tan populares como las que hacemos, cinco funciones son muy pocas, porque ya está todo vendido desde hace meses. Mucha gente se va a quedar con ganas de verlas. Las razones de la restricción, no las conozco. —Hace más de veinte años vive en España. ¿Cómo son sus sentimientos hacia ese país y hacia la Argentina?

—Yo soy un hijo de la Argentina y allí donde vaya por el mundo

siempre se me llama “el artista argentino”. El orgullo es siempre el

mismo: que me sigan llamando “argentino” hasta la muerte. —Me gusta ver el buen deporte. Ver jugar al Barcelona o al Real Madrid es un ejercicio estético: esta gente juega fútbol casi artístico. Ahora, juega la Selección y el país entero se identifica emotivamente. Argentina o España: si alguno de los dos queda descalificado, sigo con el otro. —¿Qué opinión tiene de la tan mentada crisis en España y en Europa? —Se habla mucho de crisis económica, pero la crisis que tenemos no es económica, es moral y no me refiero a España, sino al mundo. Es de principios. La crisis económica es una de las consecuencias de esa crisis de principios. Crisis económicas, la humanidad ha tenido y va a tener muchísimas y ha salido de ellas con mayor o menor esfuerzo. De lo que se sale con mucho más tiempo, dolor y pagando consecuencias más graves, es de las crisis morales. Y eso me preocupa mucho más.

|

|

|

|

| Note: this is a straight from the computer translation, without any effort to make it read better or more intelligently. Consider it a very general guide.

Back to Teatro Colon The Argentine tenor returns to the country to present Cavalleria rusticana and Pagliacci. He lives in Europe and believes that the crisis is global and not economic but moral.

The Argentinian tenor Jose Cura is based in Europe, and his career excels in all continents. However, in your busy schedule-their upcoming appointments they are in Beijing, Bratislava and Stockholm, and already has made artistic commitments until 2018, there are spaces for our country. In 2013 and he had come to do Otello at the Teatro Colon, as an actor, director and set designer. In 2015, he is back, also in this triple role, which adds a fourth, illuminator. He's here to make five functions (days 14, 16, 17, 18 and 21 July) of an opera double that moves to Buenos Aires Coliseum production Opera of Wallonia, Liege, Belgium. It's Cavalleria rusticana by Pietro Mascagni and Pagliacci, by Ruggero Leoncavallo; in the latter, Cura himself takes the role of Canio. How would you describe the Teatro Colon at the moment? Although I am Argentine, and the theater is my first house, I keep arriving as a guest. I see changes, see efforts. And beyond the problems that can have such a monstrously big theater like the Teatro Colón, the human factor is what always makes things go forward. People from Colón loves the theater, he wants his work a lot, and are artists of race, until the engineers. With regard to 2013, I feel there is a little more serenity. They have tweaked and updated salaries, which makes it very well psychologically to everyone. What analysis can you make a show like that you have made only five functions? Theater-a machine that has the Colón would have to do many more features per year. This has to do with a desire to do, but with the budget. For as popular as we do operas, five functions are very few, because it is already sold out for months. Many people will be eager to see them. The reasons for the restriction not know. Over twenty years ago-he lives in Spain. How are your feelings toward that country and Argentina? I am a child of Argentina and wherever you go in the world always called me "the Argentine artist". Pride is always the same: to continue calling me "Argentine" until death. And how do you live this footballing? I like to see the good sport. View play Barcelona or Real Madrid is a cosmetic exercise: these people play football almost artistic. Now, the team plays and the whole country is emotionally identified. Argentina or Spain, if either of them is disqualified, still another. What is your opinion of the much talked about crisis in Spain and Europe? He talks a lot about economic crisis, but the crisis we have is not economic, moral and I is not talking about Spain, but the world. It is the beginning. The economic crisis is one of the consequences of this crisis of principles. Economic crises, humanity has had and will have many and has left them with more or less effort. What he gets away with much longer, paying more pain and serious consequences, it is of moral crisis. And that worries me more.

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

.jpg) |

|

|

.jpg) |

||

.jpg) |

||

|

Pag @ Teatro Colón 2015 -- Screen Grabs

\

|

|

|

|

||

.jpg) |

|||

.jpg) |

|||

.jpg) |

|

|

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

Note: This is a machine-based translation. It provides a general idea of the article's contents but should not be considered definitive.

Cavalleria Creole, the Day Gardel Sang in the ColónTintaroja-TangoNicolas Cobelli17 July 2015I’m on the fifth floor of the Teatro Colón and can see absolutely everything. The bronze masks that decorate the proscenium, the names of some of the best composers in history surrounding the dome painted by Raúl Soldi. I watch and wait. In a few minutes the performance will start. The quote: Two classic operas of Italian Verismo, Cavalleria rusticana by Pietro Mascagni and Pagliacci by Ruggero Leoncavallo. I’m excited because this is the first time I have come to see an opera in the Colón, but with this very special feature: it is not an official performance, it is the dress rehearsal before the premiere and the theater has decided to open it to the public. To tell the truth it is a performance that is not missing any ingredients, a test run. And to my enthusiasm we add that the main character of the night is José Cura, who has three responsibilities this time: he is the stage manager, the lighting director, and if that wasn’t enough, he was interpreting Canio, the man character in Pagliacci. The first bars of the Orchestra for the Colón , directed by Maestro Roberto Paternostro, are heard and the adrenalines starts to spread among the souls present as a magic elixir that manages alchemy in the same line, even for a few hours (something which only music can achieve). Finally the curtain rises but what you see on stage is not what you imagined, not what you had heard. My mind takes a few seconds to recognize what’s going on. Tonight I came prepared to see and hear something else and now I need to rearrange my perspective and ask myself what it is I’m seeing andhearing. Yes, yes. It’s Gardel! The voice that is heard is Carlos Gardel singing Caminito, by Juan de Dios Filiberto and Gabino Coria Peñaloza. The set is not the streets of Sicily as stipulated, even the clothes are different. The singer is Carlos Gardel and the landscape is the Caminito in La Boca, the Caminito of Quinquela Martin. There are lamps, cabblestones, a bar, “a button that plays round pa don’t fall asleep” […]. Then I smile like a baby and as a tanguero my chest swells with pride to see such a scene, nothing more and nothing less, in the Colón. This marvel came from the restless mind of José Cura. More than a lyrical singer. An artist. The type who appropriates works and produces plays and does not stay with the superficiality of them but dives it its true message. On this occasion he transplanted the stories of these operas into La Boca as a tribute to the Italian immigration to Argentina. And if this artistic prowess and all the artists who participated in it (huge artists all) is admirable, it is also remarkable that it is of little importance to Cura what the critics will say. Those who come to put a division between classical and popular, who only listen to the musical notes, bold voices, bizarre bandoneons, the end of the endless tango, and all the cliches in both genders, those seek the shock only in the virtuosity and not in the artistic event. Who would not like to hear something done well? But something else also matters—expression. This production has both. And Gardel. Readings Cavalleria Rusticana basically tells the story of Turiddu, a soldier who had returned to his village in Sicily to be reunited with Lola, his fiancée. But he learns that she has married another man: Alfio, a carter for the village. Everything that happens on this Easter day will inevitably culminate in a knife fight after a toast with his opponent. This opera reminds us tangos such as "Honor Gaucho", "Brindis de Sangre", "Duelo Criollo", "El Ciruja" and many others with similar themes. Tangos from the simplest poetically speaking, but unbeatable classics. A duel for love affairs is the fastest reading that may be made of the story, but for me Cavalleria also references Borges’ "the man in the pink corner" of Borges or Bioy Casares’ "the dream of Heroes" of Bioy Casares, more complex reading and with a deeper message: the tragedy of a man who is willing to risk his life for honor , betrayals, hopes blighted by a third party, revenge, manliness, courage and human beings with their miseries and virtues. This is what Cura sought to transmit with his staging. And there is a third reading, a metaphorical one, explains José Cura: “Turiddu and Santuzza are diminutives of Salvatore and Santa. Turiddu’s mother’s real name is not Mamma Lucia but Nuzia, which is, in turn, diminutive of Annunziata, so it’s Annunciation. Lola is short for Addolorate, Dolores in Spanish. And if that is not enough, the story of Cavalleria takes place at Easter: as such, the Savior, the son of Annunciation, dies on Easter after being betrayed by a Dolorosa and sold by a Saint. And even more: the ceremony in which Salvatore is delivered is a toast with red wine: a right of blood.” Tango and the Opera The opera has influenced the songs of tango since from the beginning. It’s first sung lyrics are nourished of Verismo. This (Verismo) is an operatic style that emerged around 1880 in Italy. It started as a literary genre and was then taken to the opera by composers such as Leoncavallo, Puccini and Mascagni. They are stories that reflect the lives, the joys and the tragedies of the common man, the workers, the poor, the neglected, the good and the scoundrels. The whores, the unfaithful, the infidels, the battered. There are many tangos that reflect these stories, and even use the names of characters in opera. An example of this is the tango “Griseta” by José González Castillo, about a young French woman who comes to the Buenos Aires suburb full of dreams of love and happiness but his story ends like Camille, the character in La Dama de Las Camelias, a novel by Alexandre Dumas which inspired Verdi to compose his celebrated opera La Traviata. In “Griseta” Castillo describes the French sweet as a “rare blend of Musetta and Mimi, with caresses from Rodolfo and Schaunard,” four of the protagonists of La Bohème by Giaccomo Puccini. He also uses the name Manon from another opera by the same composer. The tango “Silbando” (also by Castillo) has another feature similar to Cavalleria rusticana but the story is set in Dock Sud, in the South Barracks (Avellaneda). The melody and leitmotiv of “Silbando” is identical to a passage in “Musetta’s Waltz,” one of the arias in the second act of La Bohème. Something similar happens with Pagliacci. There are several tangos that reflect the tragedies of men and women who work in Creole circuses, circus people, poor artists like the magician who is described by Raúl González Tuñón in his poem "Johnny Walker". Neighborhood circuses like the one of the famous clown Frank Brown. Stories of artists who must deal with the adventures of nomadic life. Thus we find tangos such as “Laugh Clown” (clear apology to Pagliacci), “Circus Girl” or “Salto Mortal,” the story of a clown who lives very happily with her partner, the circus manceau until a wealthy rancher arrives one day and she is seduced by his promises of fortune and she abandons the noble clown, who is observed afterwards on the stage of the trapeze and throws himself into the void while the children watch the tragic spectacle. Another tango with deeper lyrics and a resemblance to the story of Canio, the clown in Pagliacci, is “I am a Harlequin” by Enrique Santos Discépolo. In this case the circus artist sings and dances to hide his heartache, claiming that the woman who wounded him romantically, whom he had pinned his hopes on, he rescued from the street before being betrayed.

“I was nailed to the cross by your serial Magdalena because I

believed in Jesus and saved you,” So there’s a brief account of some tangos related to opera. But it is not only on the poetic plan that it has influenced tango but also in the interpretation. Carlos Gardel, the greatest vocal exponent of the tango, always admitted to being a fan of Enrico Caruso, Tito Schipa, Beniamino Gigli, and Tita Ruffo. I even managed to begin friendships with some of them and with Ruffo I even managed to take some vocal technique classes to give testimonies to the time. Not only was Gardel influenced by opera singing, he was the first to implement the technique in popular Argentine music (a silly thing of achievement). If we listen to recordings of Gardel in 1912 and compare them with those recorded in the 1920s, we can hear the enormous vocal and musical progress. This was due to his studying opera singing with maestro Eduardo Bonessi, a renowned teaching of singing within tango, from 1919. Besides Gardel he had student singers like Alberto Gómez, Floreal Ruiz, Alberto Marino, Azucena Maizani, Ignacio Corsini and Roberto Maida, among many others. Another scholar of the canto lirico was Edmundo Rivero, who even wrote a small book on this topic and on the voice of Carlos Gardel. Tango at the same time managed to get into the taste of famous tenors such as Tito Schipa, who recorded versions of tangos such as "Confession", "La Cumparsita", "Vida Mía", "where these heart", "Tell me by ear" and even ventured into composition with his tango "El Gaucho" which he recorded in 1928 and no less than in New York. But though the tango first arrived in 1910, Gardel could never sing at Colón though across its stage have passed the greats of the genre. So far, I hear his voice from the fifth floor of the Teatro Colón with a baby smile. Today, I came to see one of the most important tenors in Argentina and the world: José Cura. And he greeted me with the voice of the greatest folk singer: Carlos Gardel. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

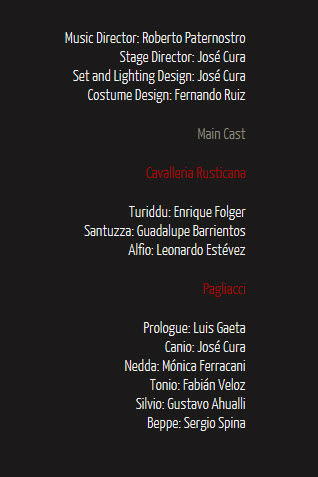

An Argentine Cav And Pag Seen and Heard Jonathan Spencer Jones July 26, 2015 [Excerpts] In a second return to his native land as a producer and participant José Cura (after his 2012 Otello) has brought his Royal Opera of Wallonia production of Cavalleria rusticana and Pagliacci to the Teatro Colón. And it is a very Argentine production, stated as a homage to the Italian immigration of 1900 and featuring the iconic Caminito in the scenery – a street full of colour, music and dance on every tourist’s itinerary in La Boca on the eastern side of the city, where many Italian settlers went and tango was born. Besides the same scenery, Cura also sought to link the two works physically, with the dead Turiddu’s funeral wake at the start of Pagliacci and an estranged Alfio and Lola and a pregnant Santuzza putting in appearances in the second work. […] Musically both works were sound, ably led by Roberto Paternostro, and notably for the Colón all the singers were Argentine. In Cavelleria, Guadalupe Barrientos particularly impressed as Santuzza, despite a bout of pharyngitis, singing with depth and passion. Enrique Folger brought his usual intensity to the role of Turiddu and Leonardo Estevez was correct as Alfio, as was Anabella Carnovali as Mamma Lucia in a role that doesn’t offer much scope and Mariana Rewerski as Lola. Cura as Canio in Pagliacci was a dramatic presence, yet sounded somewhat restrained compared with his Otello (of which I was reminded, although hardly necessary, when the opening section of his 2012 production was shown when he was presented with the Mention of Honour “Senator Domingo Faustino Sarmiento” for his achievements in the week before this production opened). Fabián Veloz was impeccable in the prologue and ably brought to life the character of Tonio. Monica Ferracani was a fine Nedda, while Gustavo Ahualli was a rather colourless Silvio and Sergio Spina an over the top Beppe.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Last Updated: Sunday, February 05, 2023 © Copyright:

Kira