Bravo Cura

Celebrating José Cura--Singer, Conductor, Director

Operas: Samson

|

Samson et Dalila, London, January / February 1996: “Due to the sterling efforts of José Cura, the young Argentinean who never seems to put a foot wrong. His Samson is full of soul; a commanding and vibrant tenor performance that captures the Hebrew leader's weaknesses with as much theatrical devotion as his god-like strengths.” The Evening Standard, January 1996

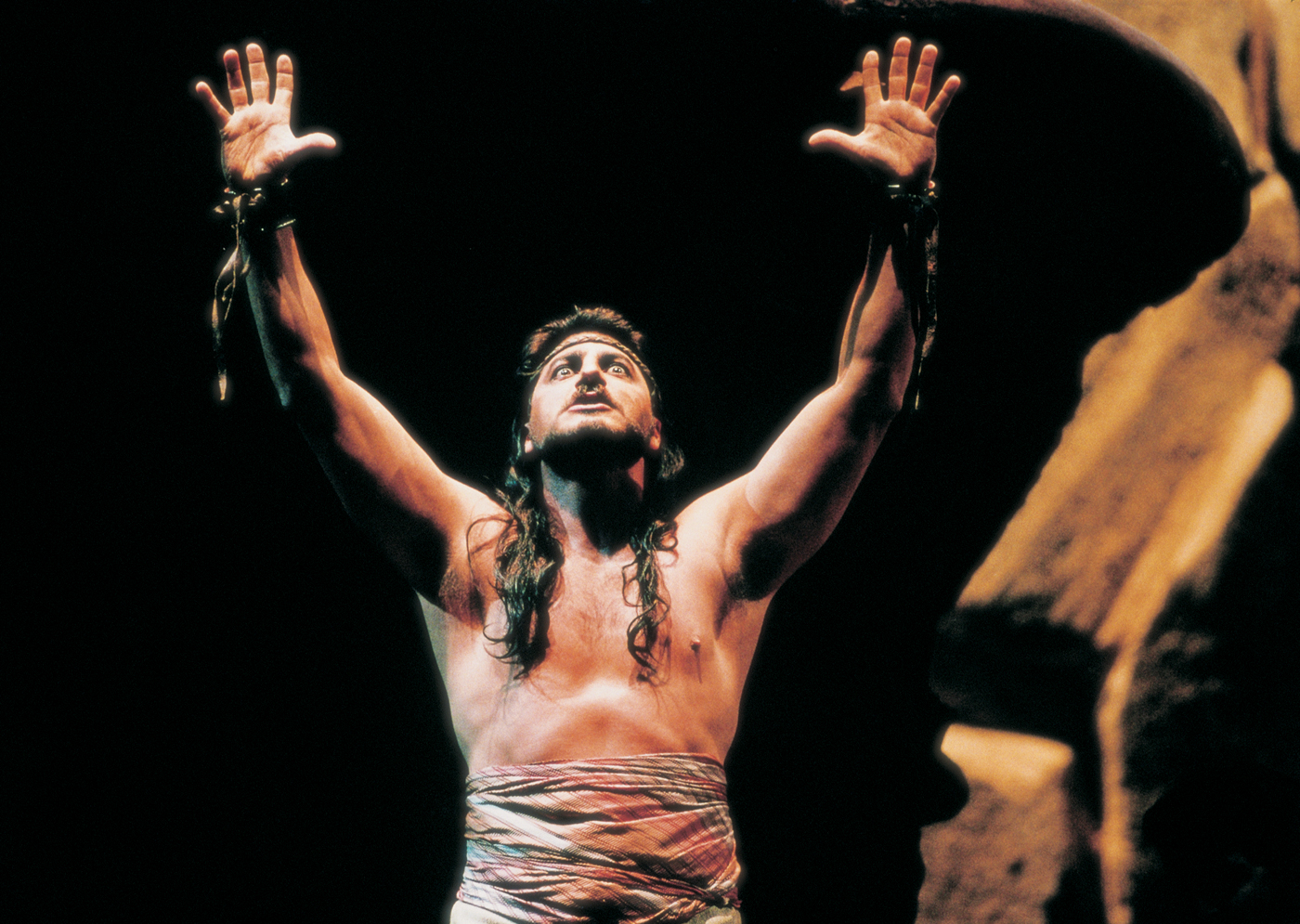

Samson et Dalila, London, January/February 1996: “At full throttle the sound is thrilling and this big, handsome man certainly brings a Victor Mature dimension to this portrayal of Samson, flaunting as much lower limb as the dancers in the Bacchanale. (And not all of it that low--I have not seen so much tenor rump on the Convent Garden stage since Peter Hoffmann accidently exposed himself in Parsifal.)” The Times, January 1996

Samson et Dalila, London, January 1996: “And there’s superbly musical singing from the Samson of José Cura, the young Argentine tenor who has made his reputation at the Garden. It’s a handsome, firm, incisive sound, and Cura makes a power presence on the stage. The audience was ecstatic.” Independent on Sunday, 4 February 1996

Samson et Dalila, London, January 1996: “José Cura adds to his growing reputation and repertoire or roles with a charismatic and sexy Samson. He generates a powerful intensity and flashes enough calf and thigh to convince he is capable not only of leading the Israelites but of inflaming Dalila’s heart—no wonder she is cross he ditched her after a single day of passion. His ardent and sensitive singing movingly projects Samson’s anguished soul. ‘Vois ma misère’ (Act III) was heartrending.” The Stage, 8 February 1996

Samson et Dalila, London, January 1996: “José Cura looks and sounds the part of Samson, strongly athletic and in very robust voice, he makes the part come alive completely.” What’s On London, 7 February 1996

Samson et Dalila, London, January 1996: “Argentinian tenor José Cura, singing Samson for the first time, gives a superb performance in the opera by Camille Saint-Saëns and proves that he is surely one of the up-and-coming top tenors of the Nineties.” The Lady, 6 January 1996

Samson et Dalila, London, January 1996: “The great thing is that he does sing softly, much of the erotic charge of the second act was the result of his sensitive caressing of the vocal lines.” The Times, January 1996

Samson et Dalila, London, January 1996: “José Cura proved a sensitive and touching Samson. His top notes in the love duet were luminous, almost falsetto, tender, and he sang a long, expansive lyrical line; yet in his final scene he managed to summon up almost raucous determination. The single greatest scene of the opera was his extended solo, pushing the grinding wheel to which he's manacled around the harshly lit circle of the threshing floor; pity and savagery blended in this complete portrayal of a man--just a man, not a hero; a man torn between emotions, brooding, [as] obsessive as the music. (Taking his curtain call, he seemed still stunned by the emotions of the role.) Moshinsky's production did not make the best of the potential of the design, failing to mass his chorus with enough power. The most dramatic moment of the betrayal is muffed. Moshinsky stand rebuked, in my mind, by the power of Cura's solo scene--so much more convincing than any of the traffic directing the rest of the production.” Our World, February 1996 Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “José Cura is fantastic. His powerful voice is able to create an atmosphere of introspective self-confession, while the timbre darkens to express the bitterness of a man who recognizes he has betrayed himself and been betrayed.” Avvenire, 1997

Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “Cura fascinated his audience with his brilliant voice, with its ample tone, perfect intonation and his powerful stage presence. As Samson, the singing actor Cura cannot be beaten.” Das Opernglas, 1997

Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “One cannot deny that the Argentine tenor gives an equally handsome and impressive vocal delivery hallmarked by mature expressivity. The color of the voice is that already familiar to us, dark and burnished, but at the same time and when needed rounded and soft. [H]e is bravissimo in the third act, singing with great participation through very refined interpretation, all of which conveys the physical and spiritual suffering of Samson.” L'Opera

Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “The Argentinian tenor gives to Samson all the strength of his magnetic presence, all the energy of a vocal emission of unseen arrogance. Cura confirms himself to be the only possibly imaginable performer for Samson since Jon Vickers’s retirement.” Opera International, 1997

Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “Bravo, José Cura! Cura’s Samson asserts his strength without undue athleticism, with particular attention to the nuances and the nobility of the score.” La Stampa, 22 October 1997

Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “José Cura was an excellent Samson, very accurate in the psychological definition of the character and credible for the voice and the appearance. “ Corriere della sera, 23 October 1997

Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “The protagonist José Cura sang very well, making himself admired also as an actor. Ronconi dressed him as Tarzan, with an ironic touch, in tune with the music of Saint-Saëns: Cura was in the game, drawing a Samson who, within the limits of the character, was really torn between duty and erotic attraction. When, blind and without hair, appearing destroyed, tied to the mill, his figure was that of a withered giant, very suggestive.” La Stampa, 23 October 1997

Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “José Cura was very good, a powerful protagonist always in possession of the role.” La Repubblica, 23 October 1997

Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “Even for professionals Samson et Dalila is a rarity: very few voices in the world have the characteristics necessary to impersonate the protagonists and among these few stands the Argentine tenor Josè Cura (already applauded as Samson at Covent Garden in London).” Il Tempo, 23 October 1997

Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “José Cura sets up his character with restrained impetus, a giant attracted to the earth and bound to her, who finds the strength to break this link only in the last scene, when the temple is destroyed. A great success for Cura …” Il Manifesto, 23 October 1997

Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “Samson—sumptuous, faithful, effective with a cast appropriate to the score [offering] great vocal richness. José Cura is a generous Samson, ardent, bold even in the high notes.” L’Unita, 23 October 1997

Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “A long final applause, which lasted for at least 5 minutes, marked the success of Samson et Dalila in Turin on Tuesday evening. The French opera had never been performed in Turin and the beautiful staging by Luca Ronconi was able to make a breakthrough with the usually not-very-warm audience. Critical reviews were also enthusiastic, some of whom spoke of this as an historical event. The two protagonists, José Cura and Carolyn Sebron stood out….” L’Eco di Bergamo, 23 October 1997

Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “For Turin, the costumes of Vera Marzot are being talked about, with her bold incursions in the faux-nude of the dancers of the Bacchanal. As for nude, much has also been said about Samson, being able to exploit the athletic musculature of interpreter José Cura, a tenor who here expressed the most vocal and stage-craft possibilities. His voice was clear and had a heroic ring, even in the most uncomfortable positions. “ Il Piccolo, 23 October 1997

Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “José Cura's voice had indubitable strong points [with] a beautiful low register and manly, well-positioned highs. The role of Samson is surely more appropriate than others to this voice, so the powerful highs in the heroic moments and the precious pianissimi in elegiac ones united with his athletic qualities and a Tarzan-like acting in making Mr. Cura a really believable Samson, perfect on stage.” OperaWeb, 30 October 1997

Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “The deeply felt aspect of the work was finally completed by the thundering interpretation of José Cura in the role of Samson; the strong Argentinian tenor concentrated on a roaring reading, painted in strong colors.” Il sole 24 Ore, 26 October 1997

Samson et Dalila, Turin, November 1997: “José Cura is a beautiful Samson for voice and physique and bare-chested roles are now his specialty.” Il Giornale, 23 October 1997

Samson et Dalila, Washington, November 1998: “There can be no denying that this is a young singer with extraordinary gifts--combining a full, ringing and powerful tenor voice (complete with marked baritonal shadings and just a hint of the trumpet) with a commanding and athletic stage presence.... the aria 'Vois ma misere' was sufficient to prove that Cura's singing is more than merely loud and hard and that he is capable of some ravishing legato phrasing.” The Washington Post, 1998

Samson et Dalila, Washington, November 1998: “Argentinian tenor Jose Cura was the evening's newcomer and focus. Would he live up to rumor and recordings? I heard a young man of noble bearing, with a pure lyric-spinto voice that had a ping of emotion and a reserve of dramatic power: exciting stuff both now and potentially. As for acting, in Samson's scene blinded at the millstone he was interior, moving and tragic.” Peabody News, November 1998

Samson et Dalila, Washington, November 1998: “The chief reason for the anticipation was the presence of the much-talked-about Argentine tenor José Cura in the title role. It is a coup for the Washington Opera to have engaged Cura before he arrives at the Met next season. He is 35 and is already being touted as the man who will inherit the mantle of Placido Domingo in the heroically scaled roles of the lyric tenor repertory. Cura's Samson in London's Covent Garden was much applauded a few seasons back, and his first performances of Verdi's Otello in Turin recently were enthusiastically received. And, as if to place his seal of approval upon predictions that the next Domingo is in our midst, the great tenor himself, who is the Washington company's artistic director and who still counts Samson among his signature roles, is making his Washington Opera debut as a conductor in this production. So how good is Cura -- or, more to the point, how does he compare with the Domingo of 20 years ago? He certainly resembles the Spaniard superficially -- except that he is better-looking and is physically more imposing than the young Domingo was. And his tenor instrument is superb. Cura's voice may not convey the sweetness that Domingo's did (and still does), but it is beautiful enough and perhaps even more powerful. Even in the highest reaches of the role, Cura's notes never betrayed a hint of strain. I also prefer Cura's interpretation of Samson (he has recorded the opera on just-released Erato 3984-24756) to that of Domingo at the same age. Cura is at least as forceful and expressive, but he gets inside the role in a way that I don't think the younger Domingo did, achieving a bottomless depth of despair in ‘Vois ma misere’ at the beginning of Act III.” Baltimore Sun, 12 November 1998

Samson et Dalila, Washington, November 1998: “Ever since Luciano Pavarotti, Plácido Domingo and [José] Carreras turned into a novelty act playing football stadiums the hunt has been on for the next big tenor. One of the strongest claimants is José Cura, a 35-year-old Argentine bringing down the house (and the set) in Saint-Saëns' Samson et Dalila this month at the Washington Opera. A kung-fu black belt and bodybuilder, he looks the part of Samson. Better yet, he sings it. Thrilling at full throttle, as any Italianate tenor must be, Cura is even more impressive as a lyrical voice in his love duet with Denyce Graves, the Delilah of the Washington production. The surest measure of his artistry, however, is his nuance vocalism and tragic characterization of the blinded Samson.” Richmond Times-Dispatch, 1998

Samson et Dalila, Washington, November 1998: “His is a voice of tremendous depth and range, knife-clean and well-supported. As an added bonus, Mr. Cura is physically handsome and robust; he makes a highly believable and sexy Samson. Mr. Cura is not afraid to take risks. His gasping voice in the last act is not the voice of a superstar tenor divo neurotically hungering for applause. At times, he chokes off his notes with a purposeful inaccuracy, intent on an honest, authentic portrayal of a beaten hero begging for God's help in one final act of vengeance. It takes guts for a young singer to do this, and Mr. Cura has courage in reserve.” The Washington Times, Nov 1998

Samson et Dalila, Washington, November 1998: “José Cura was a compelling Samson ….” Opera, January 1999

Samson et Dalila, Washington, November 1998: “Advance publicity and fan page gush do not exaggerate Jose Cura's compelling physicality, admired on November 18, midway through the run of Washington Opera's Samson et Dalila. But most impressive is the way he puts the eye-candy at the service of a deep identification with his character. Clad in dazzling white, he bestrides Act I, a monument of physical strength and moral authority. His capitulation to Dalila comes as the all-too-topical downfall of a charismatic leader conquered by his own compulsions. Like an addict entering withdrawal, this Samson collapses into a passive heap upon Dalila's cushions -- muscles limp, eyes glazing. The effect is devastating. Dressed in tatters, smeared in blood, and nearly doubled over as he pushes the millstone, Cura in Act III embodies the character's abject shame with Strassbergian realism, setting up the final act of restored faith and divine retribution for a thrilling conclusion. Oh, and he sings, too. Offering more punch than ping, Cura can't shake that "baritonal" label. Act I, where Samson is a kind souped-up Bach Evangelist, found him wanting in declamatory zeal and clarion edge. In Act II, he crooned a series of hooty "je t'aime"s, adding dubiously supported tone to his portrait of erotic submission. But in Act III, Samson's physical misery and moral torment paradoxically liberated Cura to a freer, Italianate attack that is clearly his natural métier. Suddenly the timbre had more juice, the phrasing more color, and the diction more bite.” Parterre Box, 18 November 1998 (Separate review): Another 'risky' tenor is José Cura; when his voice and personality are clicking, he can be, I think, the most exciting singer of opera today. Certainly his Samson with Washington Opera was a 'demented night (to use a useful term of supreme praise): Cura's feral voice and film-star physical attractiveness limned the tragedy of a political superman brought low by his own sexual urges. He whimpered the line "Dalila, Dalila, je t'aime' in a wavering falsetto, drunk with lust and trembling with self-loathing....

Samson et Dalila, Barcelona, 2001: “Cura sang Samson--an opera that he knows perfectly--with spirit, guts, and a taut and vibrant voice which gave to his character a dramatic force that corresponded to the action on the stage. Few times have we heard the sad monologue of the mill-turning sung more emotionally, dramatically, and movingly than from the mouth of José Cura. Then, in the Bacchanal, his performance was immense, without neglecting the vocal demands: he thrust himself into the crowd, rolled towards the ground in his knot of chains, and rose up to bring down the pillars of the blazing temple with a high note that sent the audience into delirium.” Vangardia

Samson et Dalila, Barcelona, 2001: “Now to the star of the show: the Argentinean tenor José Cura. He is a stage animal. His presence has such electricity it is almost impossible to take your eyes off him. He simply fills the stage. The magnetism is captivating to the point that there are more opportunities to be trapped by the eyes and become more indifferent to the ears. After 'Arretez, o mes freres!' the vocal problems were exposed... yes, everything was there to be heard, but his presence and acting convinced that he was Samson. Vocally there was little difference between the heroic character of the first act and the tormented lover, struggling internally and finally seduced in the second, until the vanquished, anguished and vengeful hero of the last act. The singing was always raw but none of this seemed to bother the audience, who clapped wildly and offered a final standing ovation. Yes, the show was undoubtedly a great triumph for Cura. Certainly he scored a public success in his debut at the Liceu. And at last I could understand the reason for the public uproar.” Emrique Esquenazi

Samson et Dalila, Barcelona, 2001: “So I watched two shows – one with José Carreras and one with José Cura - very different from each other. This is a great opportunity, especially since I think that José Cura, because of his interesting voice, interesting interpretation and great appearance, is one of the most interesting tenors of the younger generation. During the first act, José Cura was a bit hidden and probably did not evoke any great emotions; by the second act, José Cura rose to the tops, singing in a strong voice and playing dramatically his role. Cura was a good tenor singing with all his notes in a beautiful voice. In the final of the third act, both tenors were great but objectively speaking, it seemed that the heroic voice of the Argentinean was better than the voice of lirico spinto Spaniard. ” Trubadur, 20 March 2001

Samson et Dalila, Barbican, December 2002: “Samson is a favorite role of Latin tenors, and José Cura has already made it something of his own. [H]is a passionate account of the role.” The Daily Telegraph, December 2002

Samson et Dalila, Barbican, December 2002: “A palpable throb pulsed through the audience around me each time Cura slid on to the stage. Such was the chemistry between the two [leads] that, by the arrival of 'Mon coeur', one of the sexiest love songs in all opera, they could not resist sidling closer to each other, joining hands, then arms, then... well, one feared where Cura's fingers might wander next as he gently crooned: 'Da-li-la' into her elegantly receptive ear.” The Observer, December 2002

Samson et Dalila, Barbican, December 2002: “Now the role is taken by the most carnal of tenors, José Cura, who plays Samson as a feral creature, barely in control of his emotions. You have a real treat in store.” The Guardian, December 2002

Samson et Dalila, Barbican, December 2002: “As Samson, José Cura appears to [stake] the part out as a prototype for the overwrought verismo heroes who let every emotion hang loose. Using all the resources of his powerful, baritonal tenor, Cura gives a characteristically unbuttoned performance that improves as the evening progresses. His first entrance may show him to be loud and somewhat cavalier about pitch, but he is most impressive when he quietens down. His characterization could be deeper but perhaps we should not expect too much subtlety in a religious maniac.” Time, 18 December 2002

Samson et Dalila, Barbican, December 2002: “The love duet before Delilah betrays Samson is one of opera's purple patches, the tingle factor a high-voltage shock, particularly as performed here by the virile, piratical Argentine José Cura. The real star (of the evening) was Cura. He gets some stick from the British critics and it's true he is more of a dramatic than a lyric tenor but he's an accomplished conductor as well as singer, and around his lynchpin role the rest of the cast were able to shine. The way his voice filled and thrilled the hall will be an abiding memory.” The Mail on Sunday

Samson et Dalila, Chicago, December / January 2003/2004: “Cura certainly looked the part of the brawny Samson and, once past the hectoring tone with which he oversang the hero's opening scene, the Argentine tenor mustered the heroic timbre and dramatic declamation needed to get him through this demanding French tenor role. He aptly conveyed Samson's Tannhauser-like struggle between faith and the flesh. His most intense and poignant singing came in ‘Vois ma misere,’ when the blinded, shackled captive despairingly cried out to God.” Chicago Tribune, 15 December 2003, and American Record Review, Spring 2004

Samson et Dalila, Chicago, December / January 2003/2004: “Cura sang with powerful dark tones, impressing the audience with his stagecraft and athletic physique. In his interpretation he showed that he was aware of his weakness for Dalila, but totally unable to resist. He had not been heard at the Lyric Opera in nine years and he received a warm welcome.” Opera Japanica

Samson et Dalila, Chicago, December / January 2003/2004: “With a superb cast headed by José Cura and Olga Borodina, Lyric’s revival of Samson is spectacular. Cura, the tall, dark, handsome Argentine tenor, has been on everybody's list of the longed-for "Fourth Tenor" since emerging on stage in the early 1990s. Mercifully, the sillier aspects of that near-desperate early hype have died down a little, allowing Cura's phenomenally rich, flexible tenor voice and stage presence time and space to blossom naturally. Saturday night, he was, both vocally and in terms of acting, the kind of sexy, noble Biblical warrior opera lovers dream about. With Cura exploiting his tenor's darker weight, Samson emerged as both a thoughtful servant of God and a headstrong warrior. A sexy-looking hunk in his short tunic, he was a magnetic figure in the opening scene, a natural leader whose stirring call to arms galvanized the dispirited Jews. Eschewing cartoonish strutting and gestures for more understated intensity, Cura's Samson was a believable young hero from his first entrance. That intensity turned the Act II love scene into a titanic struggle worthy of both its Biblical authors and Saint-Saëns' gorgeously crafted score. Cura's Samson was acutely aware of his weakness for Dalila and the danger his liaison posed for his people. But the ultimately disastrous clash of his passion with the savvily deployed tears, caresses and curses of Borodina's irresistible Dalila was as riveting to watch as an impending train wreck. Highly recommended.” Chicago Tribune, 15 December 2003

Samson et Dalila, Chicago, December / January 2003/2004: “With two principals who bring large voices, exemplary physical appearance and incandescent histrionic gifts, Samson et Dalila flames up as it rarely has in its century-and-a-quarter lifespan. Cura was a powerful, subtle, ultimately profoundly moving leader of the Israelites. He has the volume, the dark good looks, the sense of stagecraft and the massive physique of a body-builder. After ranting a bit in the first act, he settled down to singing of nuance and purpose. In the first scene of the final act, pushing a millstone, he made Samson's anguish heartbreaking and he lifted himself in the temple scene to the final note that brings down the house - literally. A noble, courageous portrayal. Not for a moment does this Samson et Dalila flag; rather, the full measure of its decadence, sensuality, betrayal and triumph resounds with clarion call.’ News-Chronicle, December 2003

Samson et Dalila, Chicago, December / January 2003/2004: “José Cura as Samson is effective from the dramatic point of view: as a warrior and a prophet he made his entrance in a modest way and then incites his people with fervor and dignity (what dignity permitted him by the short tunic he dresses in during all three acts). From the dramatic viewpoint, his highlight is not the intimate second act, where Olga Borodina as Dalila dominates, but the third act, where the tragic and pathetic vein of this singer finds a vent in the lament ‘Vois ma misère’ and then in the pressing rise towards the final invocation to God and the destruction of the temple.” L’Opera

Samson et Dalila, Chicago, December / January 2003/2004: “Smoldering at the center of the Lyric production were José Cura and Olga Borodina. The Argentinean tenor was last seen here in 1994, a promising young talent subbing for Plácido Domingo in Fedora. Cura returns an international star in what has become a signature role for him, and with good reason. He unleashed torrents of ringing heroic tone within a dramatic conception that remained convincing, from the eroticism of the Dalila interludes to the poignant connection with the child in the final scenes. His voice seemed to gain power through the evening, yet he maintained the necessary control for some delicate pianissimos in the opening of Act III. Cura’s is not a refined sound, and there is a certain lack of French elegance; but this is an exciting performer who here provided a wealth of visceral thrill.” Opera News, March 2004

Samson et Dalila, Chicago, December / January 2003/2004: “The exceptional cast was able to provide long stretches of suspended disbelief. Though not always fully in control of his singing, José Cura achieved moments of great vocal power and dramatic intensity as Samson.” Opera, June 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “[From Cura] out of nowhere comes a burst of splendidly heroic singing or the fine etching of a sensitive musical point.” The Telegraph, 16 March 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “José Cura makes a forthright tenor noise as Samson and judges his histrionics with taste.” Financial Times, 15 March 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “José Cura gives a performance of great power, so obviously the chemistry is just right between these two great singers. It is not always so, but when it happens, it produces sparks of magic.’ What’s On, 24 March 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “Lastly, there was José Cura, commanding of aspect and with a nice line in suffering and staggering for the Act 3 solo. It would be churlish to linger on the mannerisms but surely he needs to iron out those now near-persistent swoops up to the note for 'expressive' effect. These tics are doubly frustrating when they accompany such splendid vocal and musical gifts, such tremendous focus at the top of the voice, and a matching ability to sing quietly and beautifully when the music needs it. By the end of the Act 2 love duet, I was teetering, almost willing to believe this opera worthy of the extravagant praise some continue to heap on it.” Opera, May 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “Argentinian José Cura, arguably the most gifted spinto tenor of his generation, is sturdy and handsome as the Israelite champion.” The Stage, 18 March 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “Cura, unsurprisingly, reacts to [Dalila] as one spellbound, tracking her every move with his huge eyes, fondling her body at every opportunity. His Samson is at once a sensualist and a fanatic, a man in whom desire and spiritual conviction burn with equal, violent intensity. His voice is in better shape than when he sang the role in concert at the Barbican two years ago. There are still moments of rawness in the tone under pressure, though he responds to Graves's seductions with honeyed whispers and captures Samson's mental and physical agony with frightening vividness in the closing scenes.” The Guardian, 15 March 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “It has to be said that [Denyce Graves] and her Samson, José Cura, looked really comfortable with each other. The body language of their fateful tryst was the one great lie that the production made believable - her deceit, his desire. Cura looks great in the role - and he sounds pretty good, too. The swarthy complexion of the voice has always been his strong selling point. And that's what counts in this role - middle-voice masculinity.” The Independent, 17 March 2003

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “José Cura is a very strong Samson: his dark tenor is in good shape with a ringing power, and he is an actor of fearless physicality.” The Times, 15 March 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “Really any production of the work needs only a persuasively butch Samson. José Cura answers the first need to a T, and, furthermore, since I last saw him in the role he has developed an amazing capacity to sing quietly, so that his assurances to Dalila after she had opened her heart to his voice that 'Je t'aime' were positively murmured. Mostly, though, he was singing at full throttle, and sounding superb.” The Spectator, 27 March 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “José Cura [brings] youthful vigour to this testing role. The dashing Argentinian finally seems to be shedding his tendency to play shamelessly to the gallery, not least to his blue-rinse groupies. In this incarnation, Cura is wholly convincing, even moving during the treadmill scene, edging me reluctantly towards a rare use of that dodgy critical word 'definitive'.” The Observer, 21 March 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “Samson … is a difficult role to fill; Cura does a good job. His voice is darker than it was last year, almost as if he was conjuring a sound suitable for the old testament prophet. Act 3 opens with Samson alone, chained to the mill wheel. Here Cura was on tremendous form...his strong performance was a striking contribution to the evening. He gave a wonderful variety of tone color, as he had done throughout the opera, and he made a profoundly moving figure. Cura's final contribution, bringing with it the collapse of the Philistine temple, brought the evening to a triumphant close.” Music and Vision, March 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “The Argentinian José Cura now ranks as one of the world's top Samsons. Large and muscular, he looks ready to topple any old temple and moves with the sass of one who knows as much his remorseful Act III aria, when shorn and eyeless in Gaza he turns the mill, had real force.” The Evening Standard, 15 March 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “José Cura reacts to Denyce Grave’s Dalila as one spellbound, tracking her every move with his huge eyes, fondly her body at every opportunity. His Samson is at once a sensualist and a fanatic, a man in whom desire and spiritual conviction burn with equal, violent intensity. He responds to Graves’s seductions with honeyed whispers and captures Samson’s mental and physical agony with frightening vividness in the closing scenes.” Guardian, 15 March 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “José Cura gives a performance of great power; the chemistry is just right between these two great singers. It is not always so, but when it happens, it produces sparks of magic.” What’s On, 24 March 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “Argentinian José Cura, arguably the most gifted spinto tenor of his generation, has wonderful moments. He is sturdy and handsome as the Israelite champion…” The Stage, 18 March 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “".....Lastly, there was José Cura, commanding of aspect and with a nice line in suffering and staggering for the Act 3 solo. It would be churlish to linger on the mannerisms but surely he needs to iron out those now near-persistent swoops up to the note for 'expressive' effect. These tics are doubly frustrating when they accompany such splendid vocal and musical gifts, such tremendous focus at the top of the voice, and a matching ability to sing quietly and beautifully when the music needs it. By the end of the Act 2 love duet, I was teetering, almost willing to believe this opera worthy of the extravagant praise some continue to heap on it." Opera, May 2004

Samson et Dalila, ROH, March 2004: “Cura found the meaty core of his dark, masculine tenor (and he looked ideal for the role).” Opera Japonica, 13 April 2004

Samson et Dalila, New York City, April 2005: ‘The Samson of the tenor José Cura, returning to the Met for the first time since his debut performances as Turiddu in Cavalleria rusticana in 1999, is the big news of the revival. The 42-year-old Argentine tenor has had an unorthodox career, which began with extensive training as a conductor, choral director and composer. He was 30 before he committed to a career as an operatic tenor. With his powerful voice, hunky physique and animal magnetism he quickly developed an ardent following. Vocal purists may still fault his singing for its lack of finesse and the sometimes patchy quality of the legato phrasing. But the clarion power and burnished colorings of his voice offered exciting compensations. Clearly a solid musician, he sang with rhythmic integrity and admirable dynamic shadings. Still, it was sheer vocal willpower and dramatic risk-taking that gave his portrayal such impact. During the love scene, he sang Samson's climactic top notes lying on his back with Ms. Graves cuddled over his chest. In the prison scene, when Samson, blinded, shorn of hair and sapped of power, turns the mill wheel to which he is chained, Mr. Cura captured the pitiable state of this broken man through his halting steps and anguished singing. Mr. Cura's Samson is the reason to take in this revival.” New York Times, April 2005

Samson et Dalila, New York City, March 2005: “Samson is a real hero of this opera and José Cura was the main attraction in these performances. His Samson is a charismatic Israelite leader, a warrior as well as Dalila's former lover. The beginning of Act III was the most dramatic, impressive and convincing moment of this staging. The captured, betrayed, shorn and blinded Samson turns the millstone, shackled to it. Effective lights illuminate the tragic leader who betrayed his nation because of his love for Dalila. Samson asked God to save the Israelites and to punish only him. His aria ‘Vois ma misere, helas!’ was one of the strongest moments in the opera. Cura is not only an extraordinary vocalist but thanks to his experience as a conductor and a universal musician, he's a rare example of a thinking tenor. That's something!” Kamerton, April 2005

Samson et Dalila, New York City, March 2005: “Saint-Saëns' orgy music inspired many a Biblical movie score, and there is a touch of Hollywood in the Met's show—most notably, in the persons of tenor José Cura and mezzo Denyce Graves. He is tall and strapping; she is regal and voluptuous; both are comely and command the stage. There is chemistry between them, as when Graves' Dalila strokes and nuzzles Cura's resistant Samson, who then follows her beckon like a helpless child. Bloodied and battered with his arms outstretched, Cura's Samson at the millstone resembles Jesus on the cross—a plausible image by the standards of Christian typology, which sees Samson's sacrifice as prefiguring Christ's. While Cura's acting was affecting, his singing was uneven. Back at the Met for the first time since his 1999 debut, he showed few signs of artistic decline or growth. His voice is dark and beautiful in its lower and middle ranges; he tends to bark his way through high phrases (though he nailed his final B-flat); and his enunciation is cloudy. His vocalism ranged from disciplined (a stirring rebuke to the Hebrews in Act I) to willful (crooning and gasping in the millstone scene).” Newsday, February 2005

Samson et Dalila, New York City, March 2005: “To his first Met Samson, Cura brought a portrayal in which spontaneous vocalism was tempered with earnest depth, both in the hero’s devout faith and in the conflict he suffered for his weakness for Dalila. Given the physique du role and a voice of heroic strength, the Argentinian tenor could encompass both rueful piety and volcanic resources of energy. With his direct manner and unruly, almost experimental technique, Cura is an exciting singer who breathes both life and thought into a character. He immersed himself in the role, putting to expressive use the arresting rough edges of his full-throated sound. In Act I, he acted and sang with restraint before rising to eloquence as he exhorted his people. Faced with Dalila, he wrestled his inner demons, emotional turmoil revving like a dramatic engine. In Act III, only sincerity and fervor saved him from hamming it up as he played out Samson’s despair in defeat. When he rose at the last moment to find himself again, the resurgence of his strength was palpable.” Opera News, May 2005

Samson et Dalila, New York City, March 2005: “Argentine hunk José Cura, whose 1999 Met debut as Turiddu proved severely disappointing, finally returned to the company with a stronger––if still uneven––effort. His Samson, in execrable French––how can such an ambitious artist permit himself this lapse?––commands heroic stature physically and, at least in the upper register, vocally, making his visually committed, dynamic assumption theatrically impressive, even if the tone itself was often unbeautiful and the technique varied puzzlingly from effective to peculiar, phrase to phrase. Cura fared best with the anguished intensity of the third act.” Gay City News, 31 March – 1 April 2005

Samson et Dalila, NYC, February 2005: “When José Cura arrived at the Metropolitan Opera in September 1999, he became the first tenor since Enrico Caruso in 1903 to be given a debut at the house's opening night of the season. But after his three performances as Turiddu in Cavalleria rusticana over an eight-day span that fall, Cura stayed away from the Met, building his career as a singer and conductor in Europe. He returned triumphantly this week in the Met's revival of Saint-Saëns' Samson et Dalila, displaying the clear, robust voice and steamy good looks that have earned him acclaim. Based on Thursday night's performance, the second in a run of seven through March 19, the 42-year-old Argentine has become a major artist. Cura combined with mezzo-soprano Denyce Graves for a moving love scene in the second act, when both took turns singing while lying on their backs. With blood on his face and his voice filled with pain, he was thrillingly dramatic as he turned the mill at the start of the third act, after his hair had been cut and he had been blinded. His French phrasing occasionally sounded less than perfect, but that didn't detract from the overall portrayal. In the post-Three Tenors era, he is among the most exciting tenors around.” Associated Press, 25 February 2005

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “The absence of a full staging leaves the voice as principal, though not the only tool to feel each of the multiple states of mind. And in this sense Cura surpassed the others with his brilliance. Flirting with some overacting but never actually doing it, Cura applied an infinite number of vocal devices to his singing, with overwhelming artistic excellence. Thus, Samson sighs agonizingly in the lamentation of the third act and his singing is perfectly audible and touching, he harangues the Hebrews almost like a Wagnerian tenor or demonstrates all his doubts in front of the lurking Dalila with an inevitable musical conviction. The first delights came when the choir, prepared by Salvatore Caputo, began from an imperceptible, perfectly tuned pianissimo, and advanced in increasing volume and intentions to build a fugue shaped with enough freedom by Saint-Saëns to allow the Hebrew slaves to sing of their despair. And when from the center of the choir, hidden among so many dark clothing, there arose the powerful, overwhelming and magnificent voice of José Cura, there followed astonishment, fascination and wonder.” La Nacion, 25 June 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “[T]he most significant aspect in this case didn’t seem to be the general concept but the expressive determination of tenor José Cura, overwhelming even when not “acting.” Cura established the drama from the “get go”, when he appeared in the middle of the choir and began to address his people simply with a look. It was evident that the limitation of the staging reflected even greater significance on the most minor inflection. Cura admirably personifies his role, as much through his acting as through his vocals. His line of singing is luscious, without cracks in the heroic registry in the first, as in the more lyrical of the second or in the whispered and broken of the third.” Clarin, 25 June 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “As to José Cura, he convinced me by the end of the performance. After a start in which he offered a very personal interpretation, one that continued until the beginning of the third act, he made a turn and frankly managed to convince me totally as an actor and as well as with his vocal delivery, emphatically projecting the drama to come and the fate of Samson and this is where I point out that without a doubt the first (two) acts are more José Cura than Samson but the third is Samson winning over José Cura and that is the key to his triumph.” La Opera BuenAyre, August 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “If a musical event depends on the presence of a great artist on stage, that is what happened with Camille Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila. The tenor José Cura, in the main role of this masterpiece of French opera, was incomparable. His vocal qualities are exceptional, his musicality ideal and the force of his delivery impressive. To this it is necessary to add his charisma. Samson has an ideal interpreter in Cura and this was demonstrated in the concert version in the Teatro Coliseo. It was not a concert in the traditional sense, but a ‘staging within a space,” as it was called, that had more to do with Cura’s lack of inhibition and his unconventional approach. Cura was the pillar of this Samson and Dalila.” Ambitoweb, 25 June 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “In the splendid opening performance of this concert version programmed by Teatro Colón, José Cura, stunning vocally and also profoundly convincing as an actor, clearly demonstrated the significance of space in heightening the dramatic effect from the start [of the opera] in his manner of interacting with the chorus. With powerful yet subtle voice, Cura took delight in the pianissimos, in raising the pitch, and even in groaning. His character literally took body and his voice became part of that body.” Pagina/12, 25 June 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “José Cura as Samson was impressive. From the initial scene, in which he emerges from the rows of the choir, his volume and commitment were captivating. In the first act he favored the use of subtlety, in the second he shaded his expressiveness to show his love, and he reached his best moments in the beginning of the third act with his concentrated painful expression and singing in a highly pleasing mezzo voce. It is possible to agree or not with his way of expressing and with some of the tricks of a singer with such solid experience but it is impossible to stay indifferent to his singing and artistic expression.’ MundoClasico, June 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “The indisputable star of the night was José Cura’s performance. From his initial appearance, almost magical, materializing in the middle of the chorus, singing as he came down the stairs to the edge of the stage, the adrenaline raced through the auditorium. His voice sounded marvelous, with excellent volume, beautiful timber—almost baritonal—the particular emphasis he put on his statements and the incredible array of vocal resources that he used. And his work as an actor carried his unmistakable stamp. Samson seems to fit him like a ring on a finger. The quality of his contribution did not waiver through the performance and he received a well-deserved ovation. Cura really is a Divo, with all this word implies. Everything with him is grandiloquent but without doubt he is one of those singers for whom every phrase, every sound he emits has a special value, a bonus.” Canto, August 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “The possessor of significant volume, solidly dramatic, the Rosarino tenor arrives in the middle of a career that has taken him to the most distinguished international stages. And this certainly absolutely justified, based on the qualities he demonstrated in his performance in the concert version of this most beautiful work, so rich and harmoniously creative, Samson et Dalila. Cura (Samson) highlighted a powerful dark tone, full of color, very supple in nuances, completely homogeneous and expressed with astonishing naturalness. And though conceptually he exaggerated somewhat his rage and the vocal contrasts of the characters (he is brave and strong in the first act…blind, weak and reduced to servitude in the last), his work showed without doubt that he is one of the principal singers of the world at the moment.” La Prensa, 25 June 2007

Samson et Dalila in Concert, Buenos Aires, June 2007: “José Cura, in the role that perfectly suits his histrionics on stage and which he was profusely and brilliantly represented, had to adapt to the modality described above. Undoubtedly, he maintains his charisma intact, his voice powerful, and his interpretation of this Judge of Israel converted in a warrior leader looking for his people's freedom is simply magnificent.” Ópera Actual, September 2007

Samson et Dalila, Bologna, June 2008: “The merit of the final scene goes to José Cura, who seems reborn and purposefully refining the interpretation of the role that fits him so perfectly. Beside him we must note, as the principal interpreter of the work, the Coro del Comunale, now in the hands of Paolo Vero who has moved to Bologna from Palermo. The rest of the cast was less convincing—Julia Gertseva combined remarkable beauty with the sensuality of a curbstone and Mark Rucker, a mediocre singer despite a significant voice (the Gran Sacerdote). It was business as usual for Mario Luperi as Abimelech. Director Michal Znaniecki did not convince. The costumes by Isabelle Comte were beautiful for Dalila, less beautiful for others, and tedious for the chorus of the Philistines, encumbered by enormous onions on their heads. Even less convincing was the choreography by Aline Nari, especially in the Bacchanal, which featured rapes and physical violence of all kinds, in absolute dissociation with the music.” La Repubblica, 2 June 2008

Samson et Dalila, Bologna, June 2008: “Dalila, the beautiful Philistine who betrays Samson for racial hatred and thirst for revenge, truly the dark heroine in the work, is Russian mezzo Julia Gertseva. She is beautiful, with a sumptuous voice, sings well, and is both musical and a musician. However, just as in Bizet’s Carmen heard recently at the Maggio Musicale, and even though this role has less weight (Dalila does not have the complex facets of Carmen) there is that necessary spark of inexpressible femininity that renders an artist an excellent professional that simply fails to materialize. Unlike the performance of José Cura. In the first act, shirt opened across his buff chest, he runs agilely up and down the metallic stairs that divides the two levels of the set designed by Tiziano Santi, with the oppressive Philistines occupying the upper level, the oppressed Jews on the lower one. One suspects the inspiration is more Cecil B. De Mille and his colossal Hollywood [epic] than Saint-Saëns, since the promise of years ago of the heroic voice is lost in the opacity of the timbre that did not ring. But if the instrument may not be what it was, any ungenerous thought is swept away in the second act, that of seduction and betrayal, where the emphasis is more intimate and uncertain to prepare for the arrival of the true emotions that comes in the third act, where shorn, wounded, and suffering, [Cura] shows himself to be a mature and sensitive interpreter, with the true timbre of an artist.” Il Sole 24 Ore, 5 June 2008

Samson et Dalila, Bologna, June 2008: “The Bologna season ended with a resounding success for Samson et Dalila, marked by the rhythmic ‘ola’ of the final applause. Principle merit must be attributed to that vocal and interpretive hurricane who answers to the name of José Cura. One of the roles felt most keenly by the Argentinean tenor from Rosario is Samson. You may have seen and heard him in action at the Teatro Regio in Turin when he caused a sensation by appearing in loin-cloth, or at the Liceu in Barcelona when his unexpected performance substituting for José Carreras resulted in him becoming a favorite of that theater. In short, there are few to turn to now for the role: with the abdication by Domingo, Cura is the only Samson. Beyond the undeniable stage presence, it must be noted in this role [Cura’s] obvious musical engagement in respect to the score and in adherence to the signs of expression, arriving at a display of unthinkable and sweet mezzevoci in the vocal surrender, where the timbre of precious bronzed amber stands out in all it manly beauty. Thus applied we want to see and listen more often but one thing more is also Cura: unpredictable. However, when he is on stage he is the catalyst who demands the attention while the other struggle twice as hard to be noticed.” L'Opera, August 2008

Samson et Dalila, Bologna, June 2008: “The predominant tessitura of Samson is congenial to both the beautiful voice of José Cura and his temperament. The broad timbre, encased in burnished velvet, is at its best in the middle tones…in the third act the singer offers the best of himself and the results are excellent, showcasing a man defeated but not tamed, making credible and touching the prolonged moral agony. This Samson, in fact, is not drawn from the religious, maintains at all time a very strong human nature with no hidden ‘divine mission,’ combining fragility and vulnerability to make the events even more tragic.” Teatro.Org, 6 June 2008

Samson et Dalila, Bologna, June 2008: “With his natural fighter’s temperament, José Cura mesmerized the audience and it would be difficult nowadays to find a more convincing Samson with the requisite quasi-baritonal qualities.” Opera Now, September/October 2008

Samson et Dalila, Bologna, June 2008: ‘With great pleasure we found José Cura in wonderful form, extraordinary in stage craft and incisive in accents and phrasing.’ GBOpera Magazine, 11 June 2008

Samson et Dalila, Santander, August 2008: “Style tenor José Cura undoubtedly has, and his beautiful timbre shone brightly in his debut in the Santander Festival. He has the force and dramatic quality necessary [for this role] and was splendid in the second act aria, ' Mon coeur s'ouvre á ta voix,' sung with Dalila.” ElDiarioMontanes, 29 August 2008

Samson et Dalila, Liege, September 2009: “Strictly balanced between the hieratic general and the psychological particular, he directed all the actors except the Argentine tenor José Cura who is allowed free rein and for good reason: the singer knows the role thoroughly, he brings to it his deep, warm timbre (habits, too) and, despite some reservations in style and diction (as his French speaking is perfect), he embodies, by his immense talent, his charisma, and his generosity, the trump card of the production. The Russian mezzo Julia Gertseva (Dalila) has a superb voice but she needs to move out of her reserve, in sexiness and cruelty, to match the fiery temperament of Cura.” La Libre, 21 September 2009

Samson et Dalila, Liege, September 2009: “Julia Gertseva, with a beautiful figure and a large mezzo voice, displayed nothing of the irresistible seducer. And she needed the sensuality to cope with José Cura’s Samson: powerful, carnal, of real presence. If in his first ‘speech’ exhorting the Hebrew to free themselves from their chains the tenor mishandle the accuracy and the line of singing in the second act as a man torn between his God and Dalila he revealed mastery of his broad, solid tonal range, from the low register to the high. Cura unleashed in the third act, painfully, tragically.” Le Soir, 21 September 2009

Samson et Dalila, Karlsruhe, October 2010: “A prominent second jobber staged the first new opera production of the season for Karlsruhe: José Cura, one of the world's leading tenors and a sensational multi-talent. And the Argentine, who is a top-level singer and also active as conductor on occasion, designed and appointed the set for his acclaimed production of Saint-Saëns' Samson et Dalila as well. That he would take on the role of Samson to boot was all but obvious. To come to the point right away: Cura knows his job, has mastered the director's craft. What he put on the stage of the Badische Staatstheater made sense. The singer-director offered up an altogether plausible version, which thankfully omitted superficial updating. Cura by no means abstained from referring to the present time; rather, he unquestionably comments on threats with which the world is faced these days. In his view, the themes molding this opera are power and domination, sex, betrayal, fanaticism, and killing driven by religious zeal. Thus, in Karlsruhe there were scenes of violence, brutality and warlike barbarity, of seduction and hypocritical eroticism, in which lust for power, hunger for revenge and unbridled blind passion characterized the actions of the main players. The high priest of the Philistines functioned as manipulator, as mastermind of this cruel game; an unscrupulous power politician, he was first seen during his big, decisive duet with Dalila in a highly symbolic way as a larger-than-life shadow projected on a drop curtain, entering onto the scene only for the final part. By contrast, the children were carriers of hope and shining lights: the Philistine children as well as the Hebrew children, who wanted to play together peacefully in spite of the opposition of their relatives and even repeatedly found ways to prevent the worst. The dynamism of Cura's production was captivating in many respects. For all its economy, the set design, a desert landscape with three stage-high watchtowers, "an abandoned oil camp" (Cura), also had an optical appeal of its own. The most hauntingly powerful moment staged was the excitingly intense and sensitively acted seduction and fake love scene, where Samson found himself continually entangled, caught in a white stage-high veil or net--code for Dalila's web of seduction. Cura was brilliant as Samson, with an exquisitely colored, sonorous, in the high notes brightly shining tenor (voice). Moreover, he delivered a highly sensitive, multi-faceted character portrayal, fascinating vocally as well as for his acting.” Rheinpfalz, October 2010

Samson et Dalila, Karlsruhe, October 2010: “The personal union of director, costume designer and stage designer does not necessarily lead to a successful artistic effort; nonetheless, this evening belonged to José Cura, towering in every respect. And while one does not have to necessarily relocate the story from the Old Testament to the present day (symbolized by three abandoned oil derricks), Cura offered a logical, and quite sensitive interpretation that was still harmonious with the original. The audience celebrated the artist with frenetic applause.” Opera Point, 17 October 2010,

Samson et Dalila, Karlsruhe, October 2010: ‘That was one of the rare opera evenings that are etched on one's memory and you won't forget for your whole life. The first night of Saint-Saëns' opera Samson and Dalila at the Badische Staatstheater ended with standing ovations and was a real triumph for all participants. It is no exaggeration to speak of a great moment of opera, one that will go down in the annals of the top-class Karlsruher Staatsoper. You really don't know where to start with enthusing- best with the super fantastic singers who made the Opera House in Karlsruhe a world stage on this evening. What an exceptional singer is José Cura, whose Samson belongs with the best! With an extremely powerful, expressive, virile, and ideally supported Italian heroic tenor, he drew a convincing portrait of the biblical hero, whom he also gave a convincing profile through his acting. With utmost élan he threw himself into his role which didn't cause him even the slightest difficulties and whose murderous cliffs he mastered with great sovereignty and distinct technical skills.” Der Operfreund, October 2010

Samson et Dalila, Karlsruhe, October 2010: “The stage is bathed in darkness; burning trash barrels provide the only light and warmth. Playing children burst onto the stage where their naive-carefree activities are broken off by the adults, in some cases by force. The adaptation and shifting of the here ever-present group of themes surrounding power, greed and domination into the children's world becomes a major element in the production's design. The Philistines in military uniform show brute force and demonstrate their merciless power over those who are subjugated. For the second act, an ultra-large white piece of fabric is fixed like a screen. In front of it are a number of white pillows, where Dalila and her attendants lounge in eager anticipation of Samson's arrival. Dalila is now dressed in a white robe (black in Act 1), but it doesn't take long to suspect that this is not the white of innocence but is used for deceitful seduction. A frame is formed in that for the third act, there is a return to the initial set. Formidable [was] José Cura (Samson), who brought his character into focus with enormous intensity. Masterly and at all times credible, he offered glimpses into the deepest recesses of his character's soul by means of his elastic tenor-with transparency and great sensitivity he outlined the conflict between unshakeable allegiance to God and love of a rival. It was José Cura's evening, outstanding in every respect. One doesn't necessarily have to shift this subject matter from the Old Testament into the present time (three shut-down derricks) but that one can nonetheless succeed in [doing so] in a very coherent manner with an interpretation that is inherently logical and absolutely sensitive, was clearly shown by this production. The audience celebrated the artists with frenetic applause.” OperaPoint 17 October 2010

Samson et Dalila, Karlsruhe, October 2010: “José Cura has a message: violence always begets violence. When the underdogs prevail they in turn become the oppressors. His message fits this opera, which the Argentinean star tenor knows inside and out. He has sung the role often and has become exasperated with productions that remain stuck in distant Biblical times. Although the story is from the Old Testament, for Cura the material is timeless. The Badisches Staatstheater gave the singer the opportunity to develop Samson et Dalila based on his ideas: Cura created the stage design, the costumes, directed, and sang the role of Samson. That’s a lot for a beginning director; Samson et Dalila is only Cura’s second [sic] production. He uses symbolic images to illustrate his concepts. Between the old oil derricks representing human greed he placed the choir and extras in a tableau with a dark orange backdrop that shows the misery of the oppressed. Children at play bring the scene to life, with the children of the victors playing with the children of the defeated until parents chase the others away. This moment is not in the libretto or the Bible. José Cura introduced the children to show that all the hope for the future lie in the friendship of the children on both side. Again and again Cura builds small scenes in which the children place themselves in harm’s way to protect their friends from the other side. At the end, when Samson buries himself and his enemies under the collapsing oil derricks, the children run on stage to symbolize a world free of violence and counter violence. Cura seeks to show that this well-known spiral is not just in the Middle East conflict by the use of torture and murder. Abimelech beats the conquered Israelites until he is killed by Samson. The Israelites celebrate when they learn of the victory of the uprising but Cura counters the victory hymn by returning [from the battle] carrying the dead. In Cura’s production Samson’s opponents, the high priest of the Philistines and Dalila, do not shrink [from violence]. The priest shoots a prisoner; Dalila is quick with the dagger and her maidens, who first appear as visions from another world comforting the battle-weary Israelite warriors, turn out to be bloodthirsty sluts who in the last act cut the throats of the prisoners. Not every symbol that Cura introduces fits together, but his message is clear. Cura shone when singing the emotional outbursts of Samson, his sung prayer for power were of impressive intensity. The audience of the Badisches Staatstheater reveled in Cura’s exceptional, wonderfully warm and powerful voice. The applause at the premiere showed real empathy between the singer-director and Karlsruhe.” Badisches Tagblatt, October 2010

Samson et Dalila, Karlsruhe, October 2010: “All-round star José Cura did himself triple credit in one swat and secured a publicity-hype rarely seen in this form for the ambitious Karlsruhe Opera House. In previous years, one had been able to experience the outstanding tenor here in several key roles of his repertoire, most recently in his signature role of Otello. He has been following his calling as conductor even at the major houses on a number of occasions and has been thoroughly successful. What is more, he had introduced himself as director with Verdi's Ballo at the Cologne Opera House in 2008. In Karlsruhe José Cura was given the special honor of directing, set designing, and singing the lead role simultaneously. The experiment was successful with only the smallest of missteps, bringing a much celebrated triumph to the theater and the singing-director. The exceptional project lent wings to the ensemble and created an artistic result that would do credit to any international operatic stage. Cura makes no effort to conceal the fact that the excesses of the Regietheater are not his style. Nevertheless, his version of the Samson story is not historical correct and seeks a middle course between a careful update and a clear focus on the core message of the Biblical drama. Camille Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila has always been difficult to stage effectively since its static chorus scenes seem closer to oratorio than to a passionate, theatrically effective opera. Set in a gloomy oil field in modern times, this production references the current potential for conflict in the Middle East without exploring more deeply the political dimensions. In this respect, the production remained a bold one, motivated by the atmospheric and committed to a point of view. For the more intimate scenes of the second act with its fateful meeting with Dalila, Cura surprised with powerful metaphors that stunned most particularly in its simplicity. The warm and enthusiastic encouragement he earned at the end was not just for the highly gifted singer-actor. José Cura left no doubt that he must still be considered in the forefront in the heroic roles such as Samson. In his baritone-like timbre, the dramatic fire of his performance and the sheer impact of his effort, but also the delicate lyricism enabled by his technique, he impressed once more. Julia Gertseva was an equal partner. This second act gave free rein to emotions and brought to the Karlsruhe opera a vocal triumph of the highest level, one which should rank [high] when writing the history of the theater.” Opernglas, 15 October 2010

Samson et Dalila, Karlsruhe, October 2010: “He would have been called a ‘jack of all trades’ in earlier days; nowadays he is multi-talented. José Cura is no longer content to merely sing. He conducts often; he has performed, for example, Puccini’s Butterfly at the Vienna State Opera. However, this tenor of the first rank wants even more. He worked as a director and set designer in Cologne with Verdi’s Ballo in Maschera, then in Nancy and at home in Buenos Aires. And now Karlsruhe-- he offers himself in Camille Saint-Saëns' opera Samson and Dalila as director, set designer and eponymous hero. No question he is able to do it. What he does is professional. It is strong and discussable and certainly not a show act for Kultur-Boulevard. Cura is surely no revolutionary director; still he does not lose sight of the present. The first and third acts do not play out in either a ‘large square in Gaza City’ or inside the temple of Dagon but instead in an abandoned oil camp. And it is not the temple that the blinded and abused Hebrew muscle man Samson causes to collapse with the help of his God—it is the drilling rigs that are beginning to topple when the curtain falls. Cura also invents [the role] of the children: that the kids (“Children are the letters we write to the future”) from warring nations play peacefully together and protect each other from their own leaders is one of the better takes. One of the visual strengths is the ‘love’ scene between the title couple. Dalila is paid by the High Priest of the Philistines to elicit the secret of Samson’s strength, his thick main of hair: an act of lying and an unscrupulous use of sexual power in the service of the state. The love scene is infamously ‘staged’ by Dalila and Cura shows this clearly–and with a simple pictorial idea of entanglement: a stage-high white curtain veil in which Samson gets caught and is literally wrapped. The unmistakable strength of the evening actual apart from a few diffuse moments in the strings was the high musical quality. Dalila was sung by the very credible Russian Julia Gertseva, slim mezzo soprano who only right at the top was sometimes a trace too shrill. And Cura the singer? An apparently fully mature steel-voiced tenor, blessed with the right material who mastered the gestures of the folk hero as well as the desperate lyricism of the humiliated. The ovation at the end seemed somewhat like an anticipated premiere party.” Badische-Zeitung, 20 October 2010

Samson et Dalila, Berlin, May 2011: “Fortunately, the protagonists were played by magnetic soloists who distracted from an increasingly fizzling production. The prominent tenor José Cura was a thoroughly seductive Samson despite a somewhat constricted vibrato during the first act. His voice loosened up for a powerful performance at the onset of the third act in which the chained hero desperately prays to God. His visceral but vulnerably expressed singing brought a palpable spiritual dimension to the story.” NPR, May 2011

Samson et Dalila, Berlin, May 2011: “Jose Cura demonstrated that Saint-Saëns' music can produce deep emotions of utmost intensity by means of the minutest alterations in sound.” Klassic, 15May 2011

Samson et Dalila, Berlin, May 2011: “This gross error of interpretation, bad taste and lack of sensitivity cost Kinmonth merciless boos and catcalls from the time the curtain fell at the interval to the end in spite of anything the excellent performances of the great Bulgarian mezzo-soprano Vesselina Kasarova and the brilliant Argentinian tenor José Cura (a Samson with enormous dramatic power and rich sound) could do to remedy. There was a standing ovation from the audience for the singers. But when Kinmonth and Darko Petrovic (co-costume designer) appeared to give thanks and take leave, the booing and catcalls reach an unprecedented level for this stage. In short, this was a production to hear rather than see.” Mundocalssico, 14 June 2011

Samson et Dalila, Berlin, May 2011: “Unfortunately, Kinmonth didn’t have the slightest idea how to inject movement into his stiff, hermetically sealed model. So it was a great shock when two cattle cars rolled onstage in the closing minutes, apparently summoned by Samson’s strength and devotion to God, to ship the Philistines to you-know-where. It was frustrating and totally incongruous with the music: the Hebrews’ revenge on the Philistines is sending them to the ovens. The suggestion would be in bad taste anywhere. In Berlin, it was appalling. Fortunately, the evening’s musical elements were less repugnant. José Cura, now in his late forties, has sung Samson all over the world. He is a powerful, forceful tenor with burnished tones and thrilling top notes, but his phrasing can be confusing and the results uneven. He had moments of transcendence and heroism. He sounded stiff and leaden in his Act I entrance (the top hat and cane may have contributed to this impression); he fared better in the love duet but really came into his own in his Act III lament and prayer to God. He projected anguished, almost cantorial tones and attacked this exquisite music with tormented, fearful precision. The evening concluded with generous ovations for the singers and satisfying boos for Kinmonth and his team.” Opera News, August 2011

Samson et Dalila, Berlin, May 2011: “Jose Cura's Samson, virile and enormously touching in the third act, does not sport a mane of long hair. The singer does without macho affectations, and at the end he is no suicide bomber, who causes Dagon's temple to come crashing down, either. Pensive, with top hat and walking cane or without, he acts the part of defender of his Lord, Jehova, God of the Jews, transcending time as it were.” HNA, 31 May 2011

Samson et Dalila, Berlin, May 2011: “Two protagonists in particular put themselves in the service of music and action with complete devotion and had inspired each other to singular levels of achievement. [A] moment of really great singing was Samson's solo scene at the beginning of the third act. Here, José Cura exhibited the full range of his mastery both as a singer and as an actor; based on excellent technique and breath control, he sang with pure, unbridled emotion, which went straight to the heart. After an initially restrained start, the singer, who has grown and matured in this role over many years, escalated (his performance) brilliantly, so much so that the big duet between Samson and Dalila was a total delight in its gripping intensity. In principle, this should have triggered a storm of applause. That it failed to materialize and instead boos and subsequent vulgarities made the rounds in the auditorium, is to be attributed to the directing, which was obviously all but insufferable for many a patron. Indeed, the director opens himself to criticism less for the radicalism of his conception than for the as yet poorly developed ability to offer workable, convincing directing and guidance. Here, the singers--fortunately deeply charismatic--were often left to manage the challenges on their own, were frozen in theatrical gestures or preoccupied with awkward, meaningless gimmicks.” Opernglas, 15 May 2011

Samson et Dalila, Berlin, May 2011: “The roles of the protagonists were taken by the extremely prominent José Cura and Vesselina Kasarova. The tenor, who has emerged over time as both composer and director, no longer sings with his original captivating ease but remains capable of intense expression, as with his dying piani, for compelling effect. He also showed special talents as an emcee when the curtain for the final applause remained down too long …” Neue Musikzeitung, 16 March 2011

Samson et Dalila, Berlin, May 2011: “José Cura looked striking as Samson and sounded great. He certainly has the physical and vocal presence that the role requires and he was consistently intense of the stage. It was certainly not his fault that this particular Samson was staged…” Operamagazine, 17 May 2011

Samson et Dalila, Berlin, May 2011: “One of the most interesting evenings of the season. José Cura in his signature role as the hero with the potent pile, i.e. with the power of an unstinted head of hair, has the perfect hair for Samson and the right (kind of) chest, too. From there he produces those steel-sobs typical for him by the dozen. Respect. Currently there is no one to match him in this. With his Otello, we had already come to appreciate that he likes to plunge into old, familiar roles in entirely new ways. Alongside Laurent Naouri and Ante Jerkunica he contributes decisively to one of the vocally most interesting evenings of the season.” Kulturradio, , 16 May 2011

Samson et Dalila, Berlin, May 2011: “Hardly challenged dramatically, José Cura concentrated his force on producing trumpet-like tones, increasingly successful as the evening progressed.” Der Standard, 24 May 2011

Samson et Dalila, Berlin, May 2011: “José Cura, who has sung Samson almost as often as he has sung Canio, has a strong, controlled vibrato and knows how to use it as a temple for his broken character, developing it was amazing vehemence and authority.” Die Welt, 17 May 2011

Samson et Dalila, Berlin, May 2011: “José Cura produced some powerful, ringing sounds, though his portrait failed to disguise the fact that the part of Samson is woefully underwritten in dramatic terms.” Intermezzo, 15 May 2011

Samson et Dalila, Beijing, September 2015: “It the evening’s performance, the world famous tenor José Cura, who played Samson, was particularly noteworthy. His was a great and glorious voice, full of dramatic tension, resonant as a warrior, tender and confused when bewitched, remorseful and sorrowful after betrayal. Especially in the third act, when Samson sang the famous prison aria “Vois ma misère, hèlas,” Cura’s singing vividly depicted his misery, confession, and sincere repentance. When Samson regains his power and suddenly pulled down the pillars, his penetrating voice was powerful, impressive.” ChinaNews, September 2015

Samson et Dalila, Beijing, September 2015: “If you had been at the rehearsal for the B cast the day before, you would have heard a young Latvian with a powerful, dramatic tenor and certainly have been roused to rejoice that here, finally, was a good tenor! But last night at the premiere performance of Samson et Dalila with super tenor José Cura, we understood that the Latvian tenor was a mere “mortal” while José Cura is the true “god”! At the end of the opera, as he toppled the temple pillars, he sent out a burst of extremely powerful voice and generated a strong aura that was absolutely shocking to the heart and soul of the audience, so much so that after the curtain opened again there was ecstatic, almost Carnival-like cheer and applause to compliment the true “god….José Cura, singer, conductor, composer, director, and photographer, is one of the world’s best Samsons. In the premiere he had a very different sound approach in every scene, so that his Superman-like character is full and strong. His grand, dramatic and explosive sound, enough to restore the “divine power” of Samson, allowed him at the last minute to bring down the Philistine temple and kill three thousand Philistines.” Beijing Morning Post, September 2015

Samson et Dalila, Beijing, September 2015: “In the premiere, José Cura was exceptionally impressive in the role of Samson, presenting a complete Samson from the sonorous brave warrior of unquestioned integrity through the man bewitched by (lusting after) flesh, finally transitioning to regret and sadness after being betrayed. Especially in the third act, when the imprisoned Samson sang the famous aria “Vois ma misère, hèlas,” Cura’s employed a tearful singing voice to offer a vivid portrait of a the misery in Samson’s heart and his sincere repentance.” BJWD, September 2015

Samson et Dalila, Beijing, September 2015: “In the National Theater production of Samson et Dalila, the singer playing Samson is José Cura. In this performance, his singing was most glorious, not only because of the open voice and the high notes suffused in golden light but in its proper dramatic grasp. Such is his vocal power, divinely manifested, that the loud, confident voice, the pianissimo is response to Dalila and the expressions of penance when he cries out to God, are all carefully managed. In performance terms, José Cura, from start to finish, had such boldness about him, whether he encouraged the Hebrews when he sang [Arrêtez, ô mes frères] or when he acknowledges his love for Dalila “May God’s lightning swift overwhelm me / I struggle with my fate no more! / I know on earth no power above thee” that it was the hearts of the audience that burned….In short, being able to watch Samson et Dalila on our home opera stage was good fortune, especially to be able to listen to José Cura sing and to witness his performance.” Beijing Times, September 2015

Samson et Dalila, Beijing, September 2015: “The story of the ‘hero who becomes a prisoner’ is an opera that can be said to be something of a José Cura masterpiece. Over nearly twenty years, in several productions of Samson et Dalila, Cura has brought his interpretation countless times to this ancient Biblical story. This, however, was his first visit to Beijing, the first time this tragic hero has appeared on a Chinese stage. … The fourth tenor in the world really did not let the audience down. Last night, his voice was full of dramatic tension for each of Samson’s “three faces.” Whether presenting the sonorous voice of the warrior in the first act, the confused lustful tenderness in the second, and finally, in the third, the sound of the betrayed, remorseful and sorrowful, Cura’s voice was always full of character. Especially in the third act, with Samson’s eyes removed and the hero secured within a prison, he sang the famous aria “Vois ma misère, hèlas;” he vividly tells of Samson’s misery with tearful singing, presenting the abject hero with meticulous accuracy.” BJRB and BJ Xinhua, September 2015

Samson et Dalila, Beijing, September 2015: “On the international opera stage, it is often said that the dramatic tenor is the hero with the “Golden Trumpet.” Last night at the National Theater premiere of the opera Samson et Dalila, world famous tenor José Cura let the Beijing audience experience a truly dramatic tenor with that gold trumpet style: Cura plays Samson as a god and from the first scene his voice was loud and clear. Even though the orchestra filled every corner of the theater with music, Cura let you feel God’s power. José Cura has performed Samson for twenty years and his countless performances have enabled him to understand the character so that not every word is powerfully sung; when he faces Dalila’s temptation, his voice becomes very gentle. Although the Cura sound is not the lyrical tenor voice we are used to, in its strong flavor and breath control José Cura grasps the emotions of the singing, changing up and down. In the Act III prison scene, when he sang the aria “Vois ma misère, hèlas,” the volume varied from weak to strong, full of emotion when singing pianissimo while at other times making a sound like a mighty bell, making this music strike the hearts of the audience with Cura’s voice changes. Meanwhile, José Cura showed his strong interpretation on the stage as Samson, displaying both sadness and anger.” Art.ifeng, September 2015 |

|

|

|

A Dangerous Cocktail Prolog Andreas Lang March 2020

[Original text courtesy of José Cura]

KS José Cura has sung many important roles at the Vienna State Opera: prominent roles as well as main characters in rarities. "His" Samson was still missing in Vienna—this gap will now be closed in March and April.