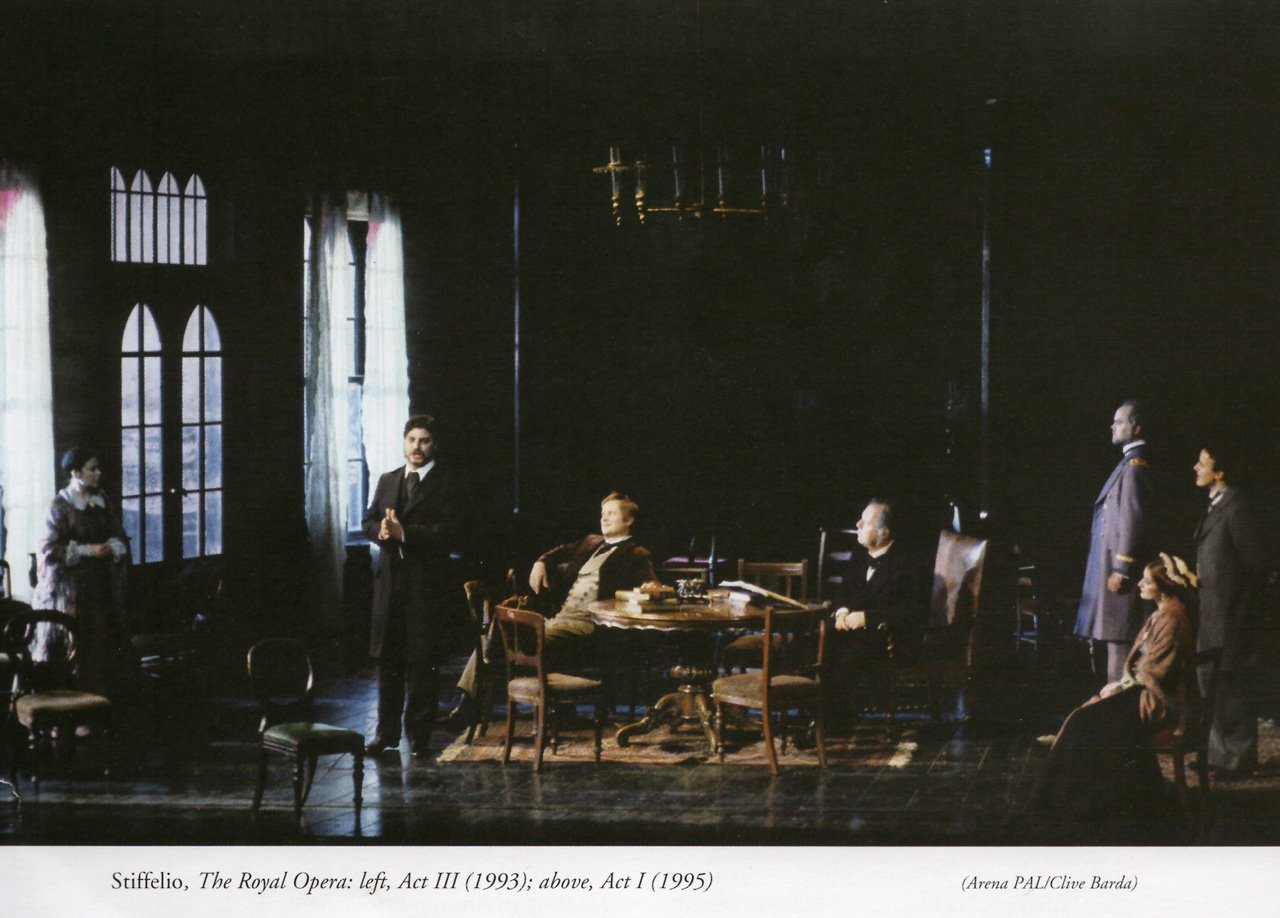

Stiffelio

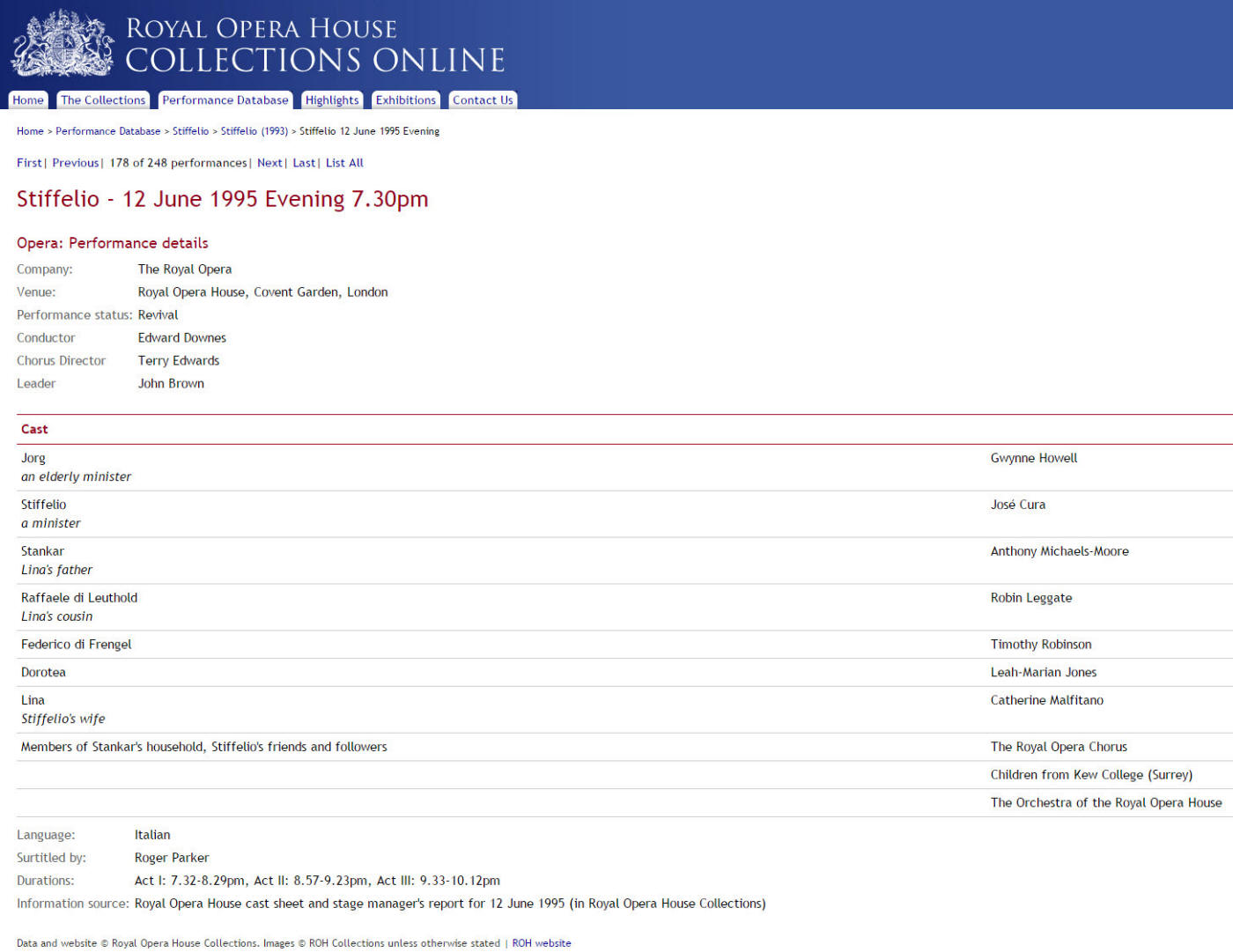

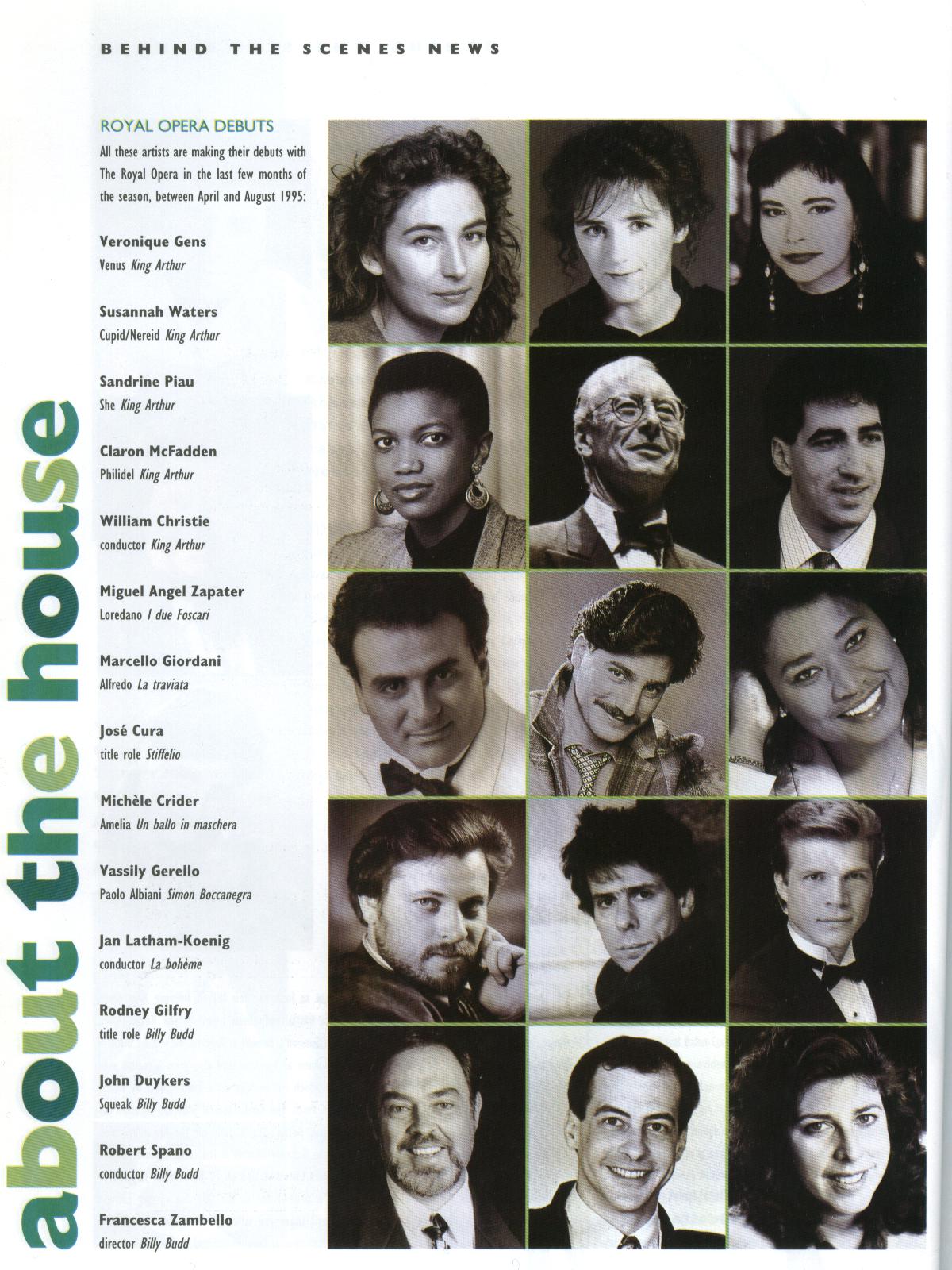

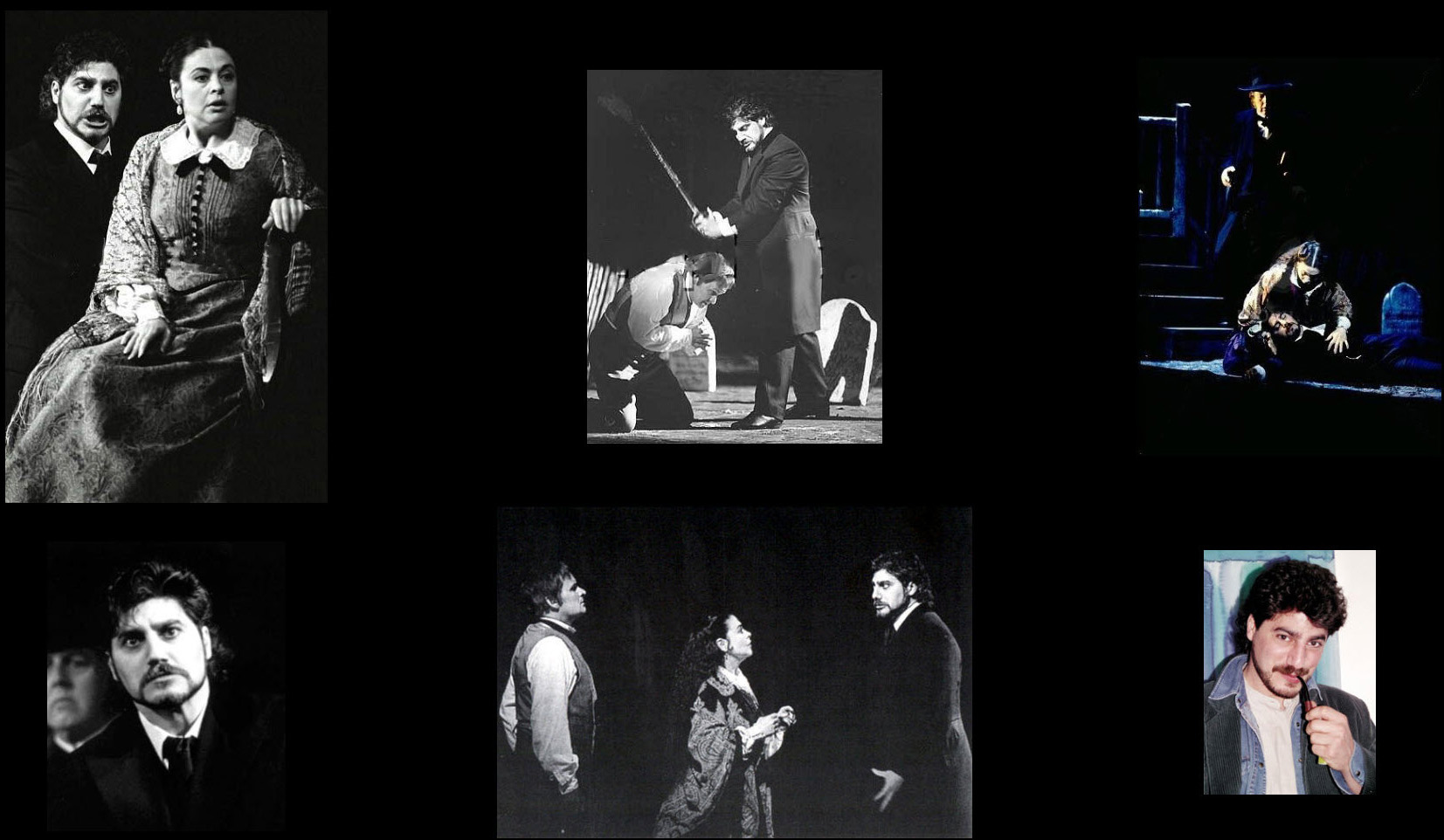

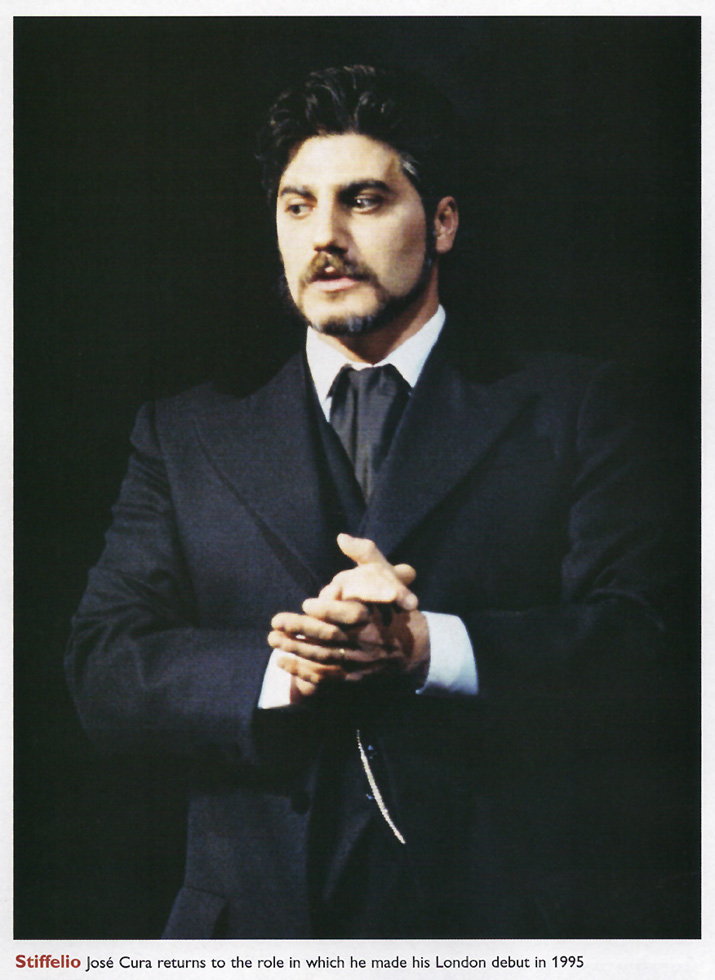

Debut -- Royal Opera House 1995

|

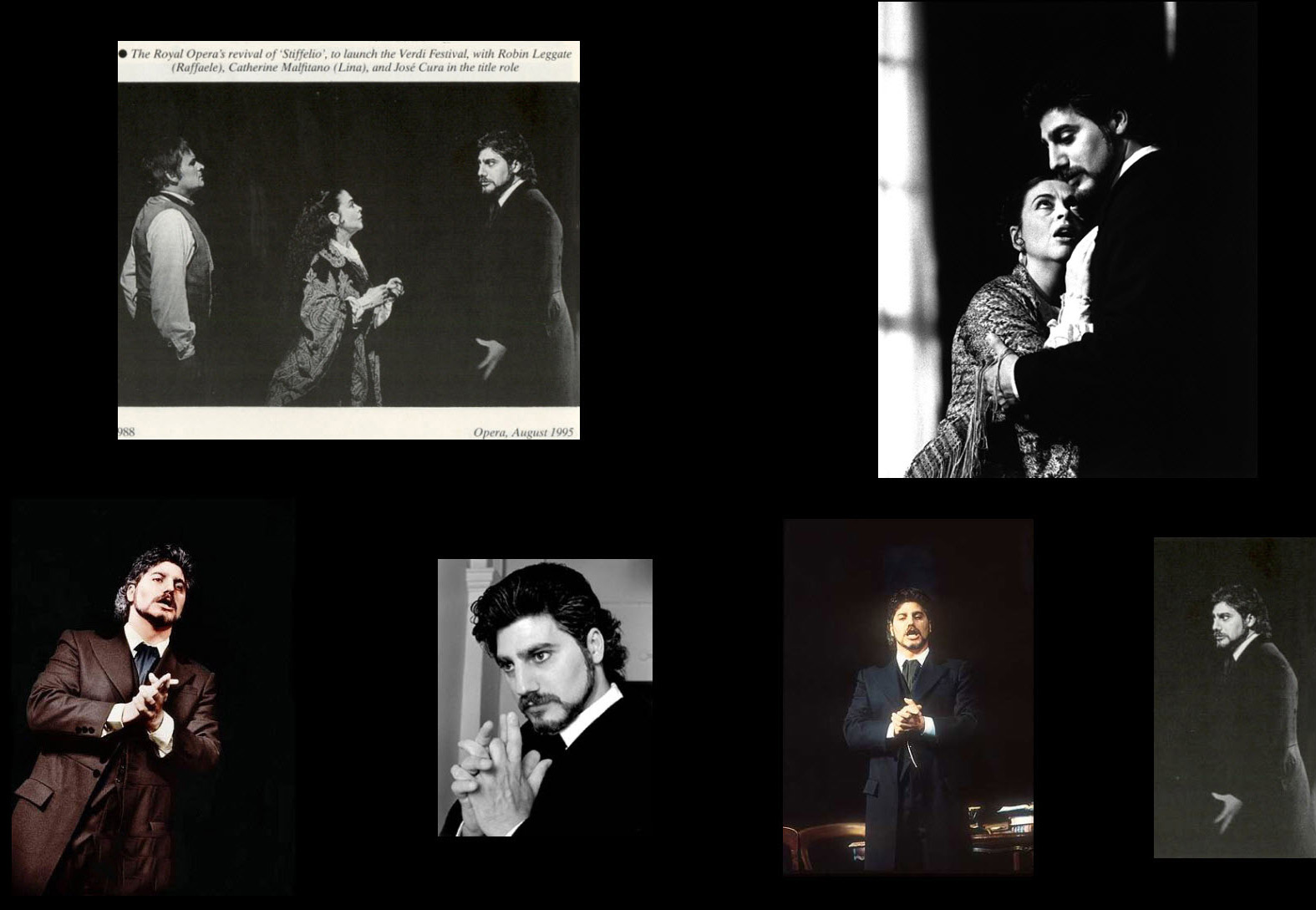

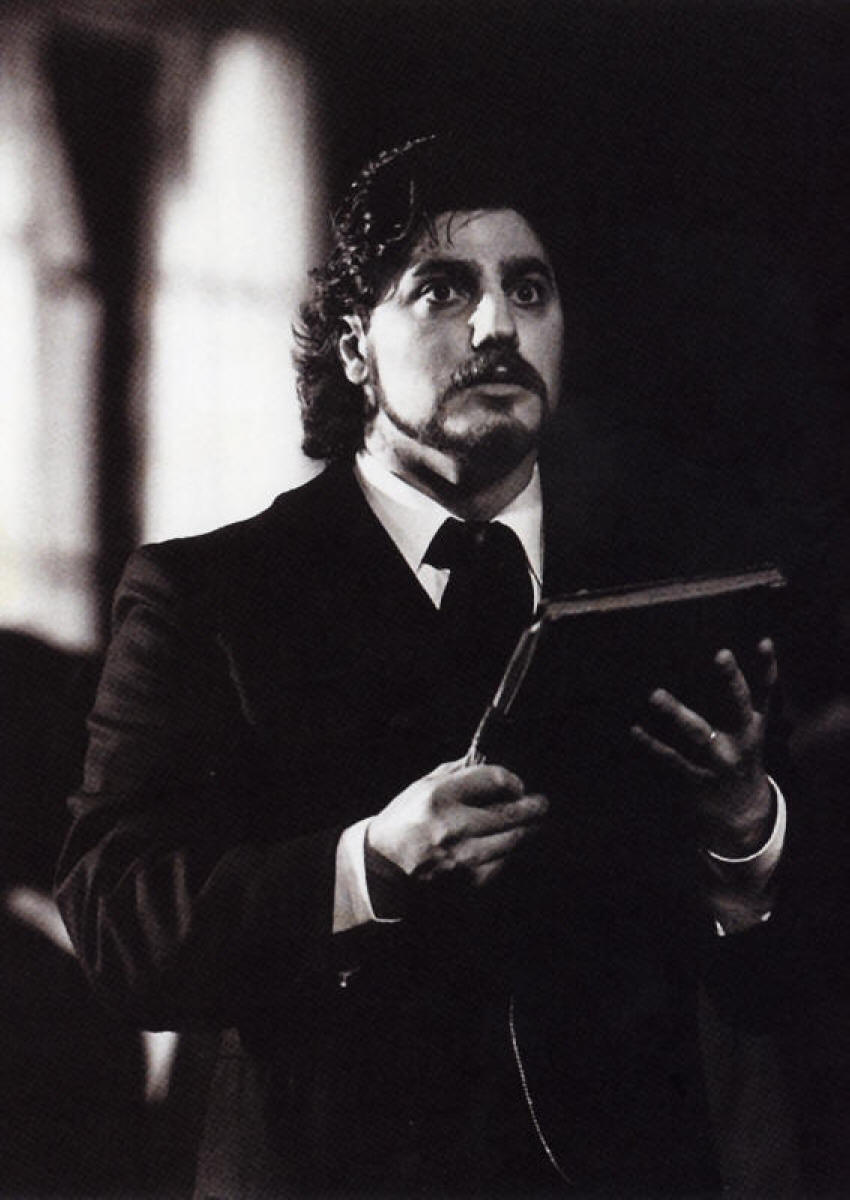

Stiffelio, London, June 1995: “What made last night particularly thrilling was the debut performance of Argentinian tenor in the title role. Are we being introduced here to another “supertenor” for the next generation? His voice is certainly of that caliber; a reedy, almost pre-war tone in the quieter passages is replaced by awesome, open-throated power at high volume. At the top of his range he can supply unlimited pressure without buckling the sound. His Stiffelio sucks the audience into a personality festering with piety, priggishness, hypocrisy and irrepressible rage.” Evening Standard, July 1995

|

|

Stiffelio, London, June 1995: “The Argentine tenor is tall and imposing of stature and the top of his voice is thrillingly free and secure. Lower down his pitch can waver and musical line is not yet his strongest suit. He has a nice line in flashing eyes and flaring nostrils, and neatly suggested the man’s fundamentalist smugness in the early scenes. Above all there is an elemental power to his stage persona which is well suited to the role.” The Times, June 1995

|

|

Stiffelio, London, June 1995: “A real tenore di forza, with a commanding stage presence and an unusually dark, burnished timbre, burgeoning unexpectedly into a brilliant ringing top, Cura is a real find, an Otello in waiting.” Independent, June 1995

|

|

Stiffelio, London, June 1995:

“Cura has an imposing, almost haughty

bearing that makes him perfect for the role of the minister whose moral

sense is ever so slightly tinged with sanctimony. His tone is ringing

and his technique reliable; only a somewhat stiffly unfolding line prevented

him from registering all the finer nuances of the part."

Opera, August 1995

|

|

|

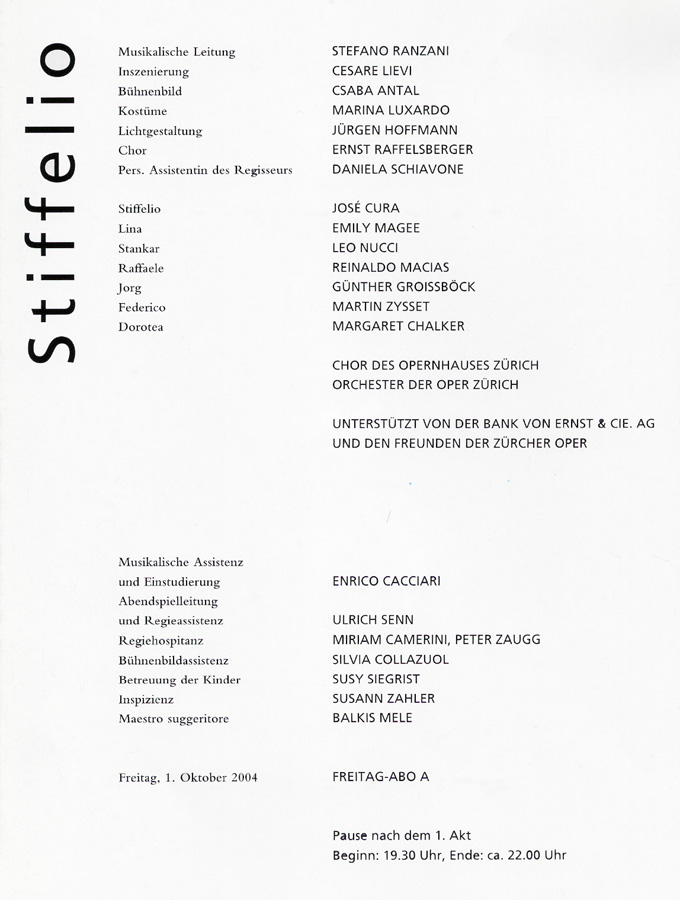

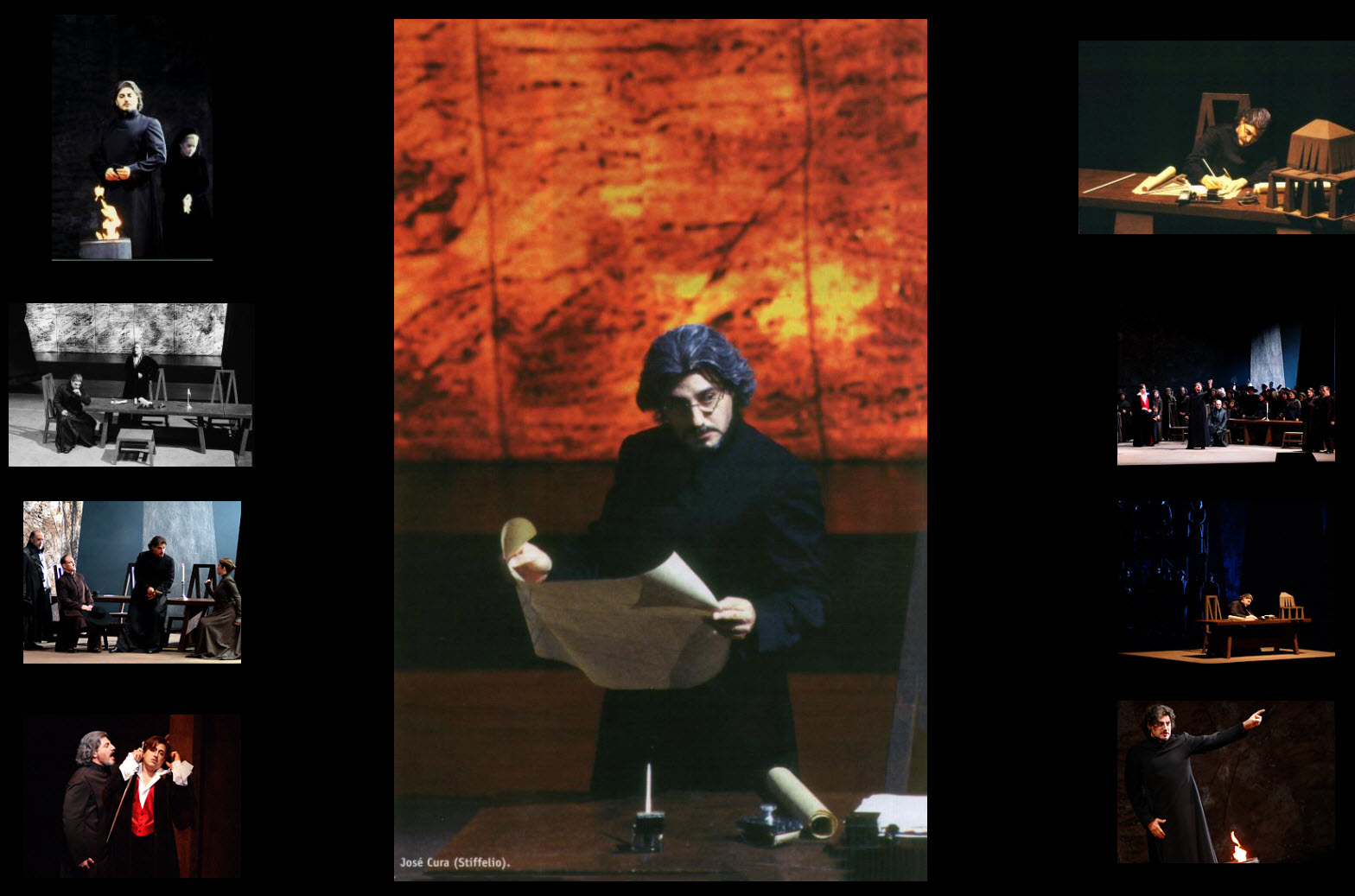

Stiffelio

Vienna 2004

|

|

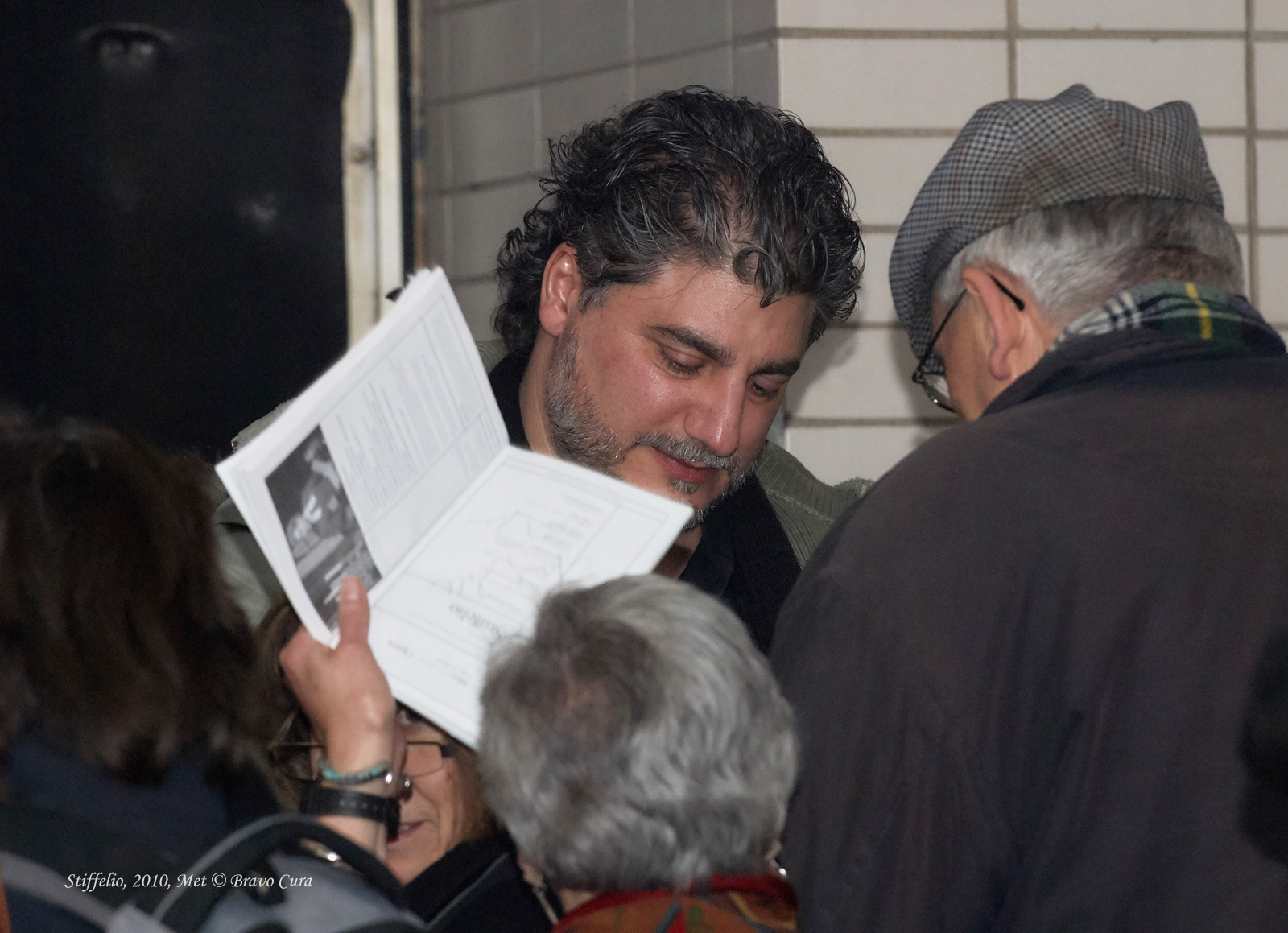

Fan Photos

|

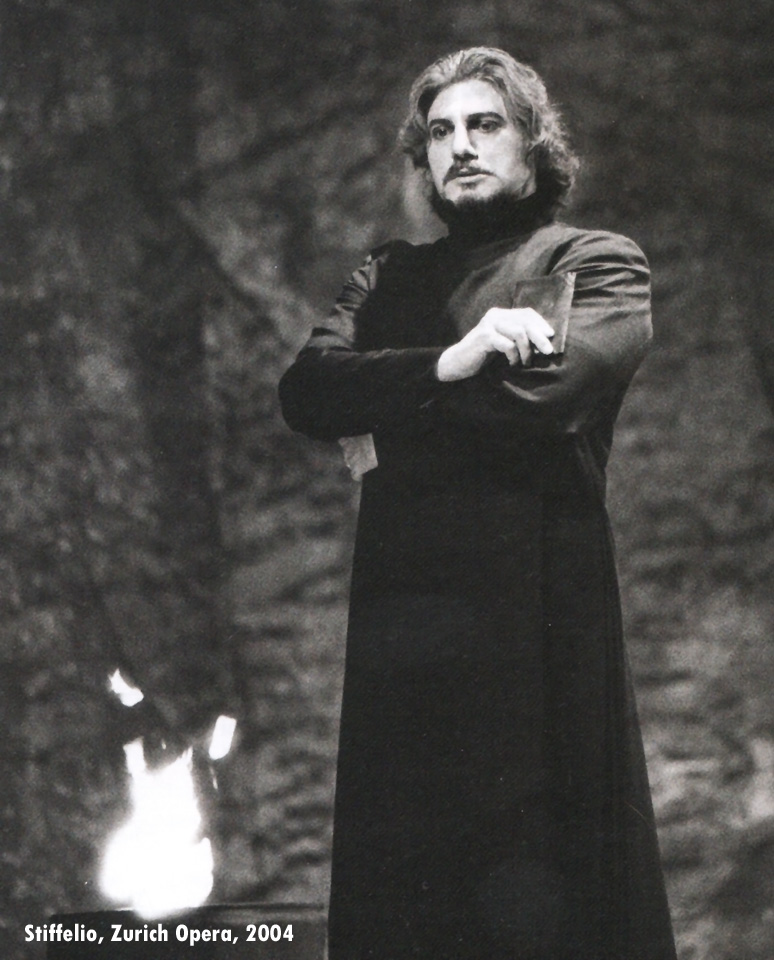

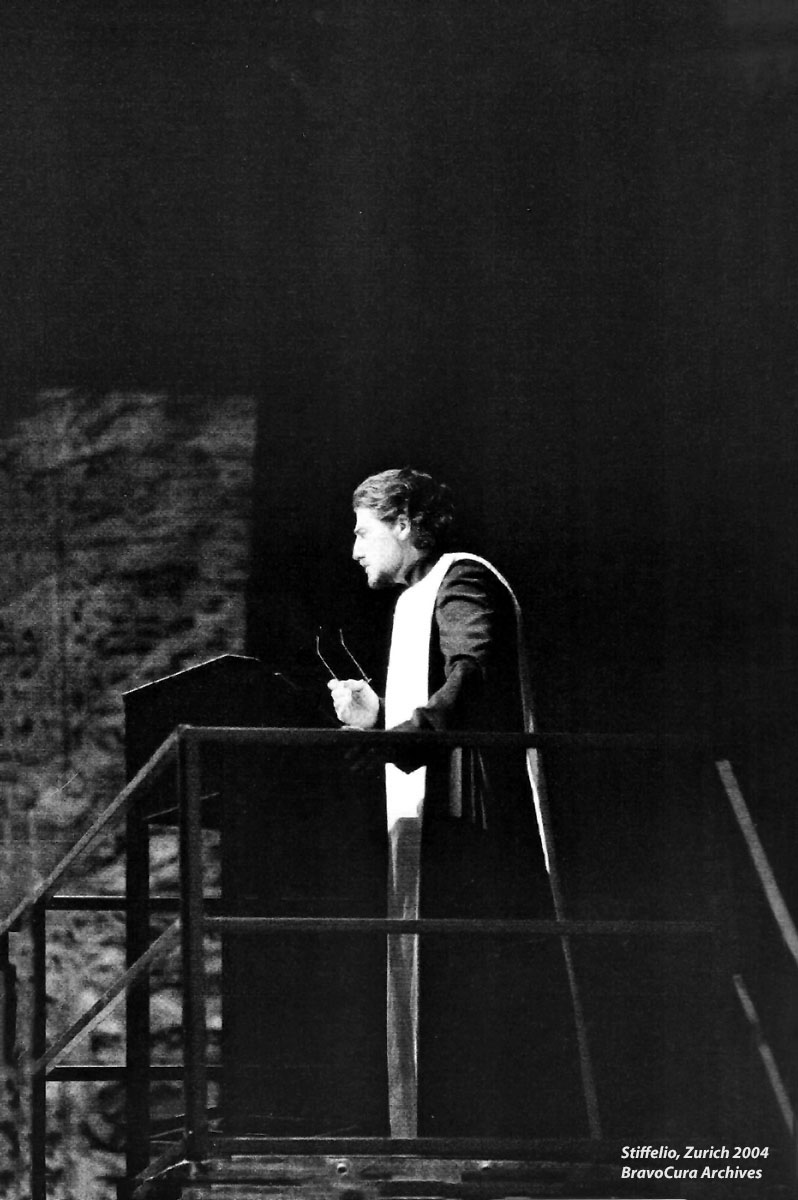

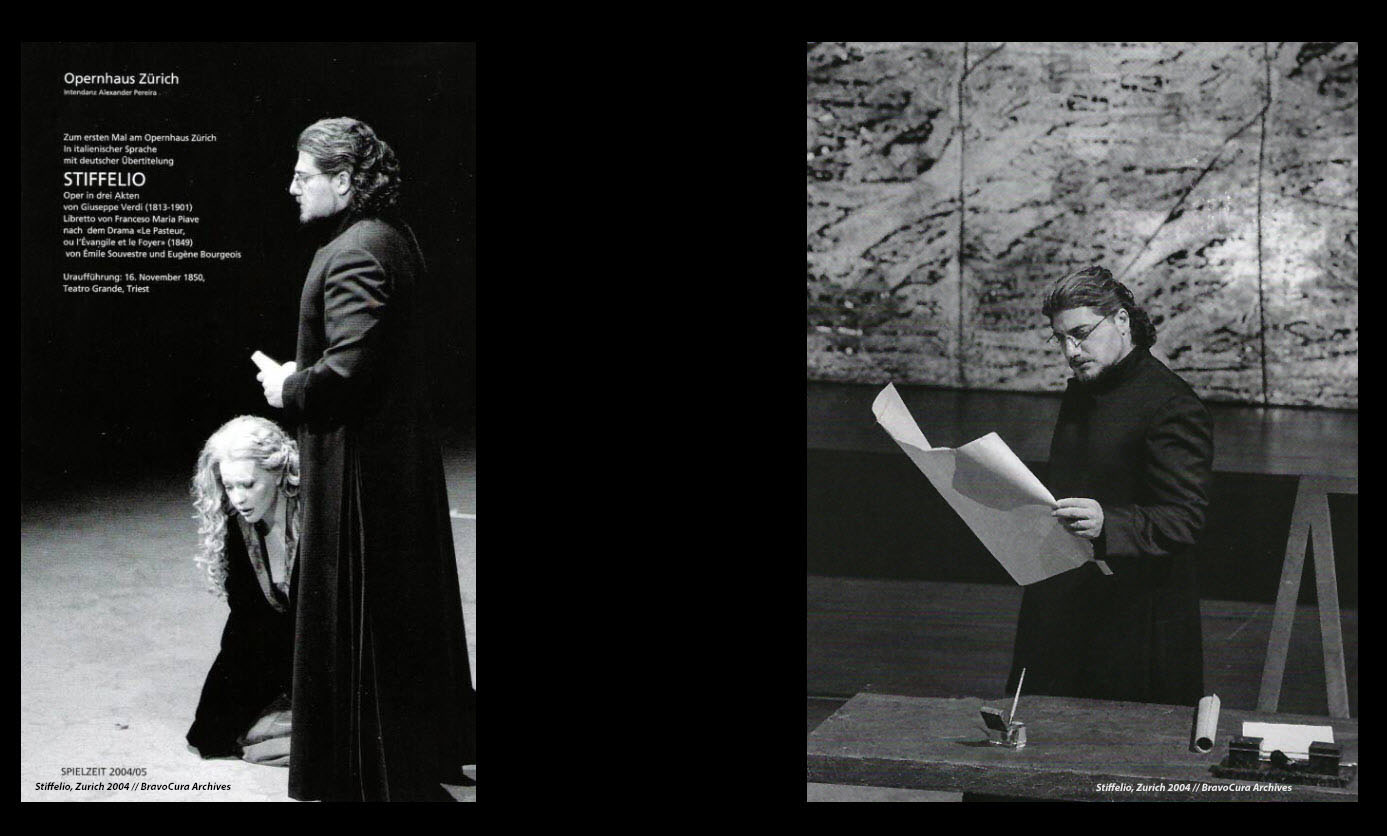

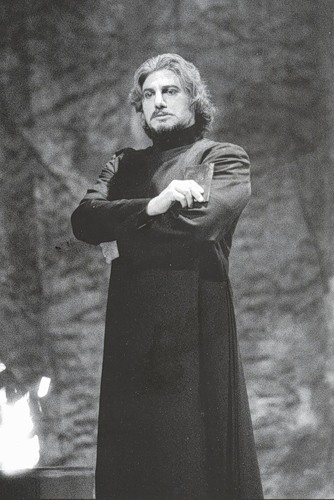

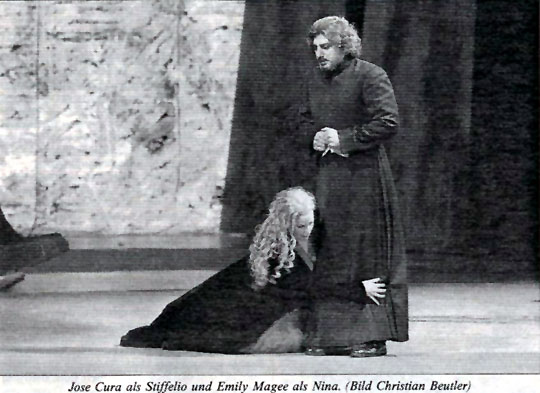

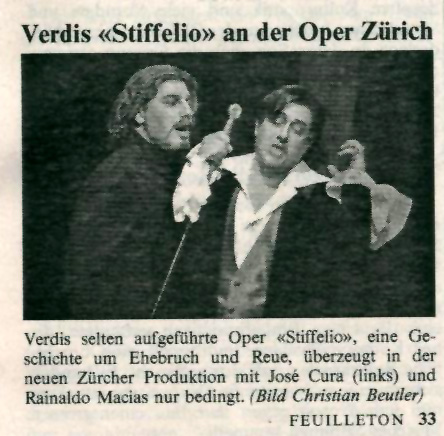

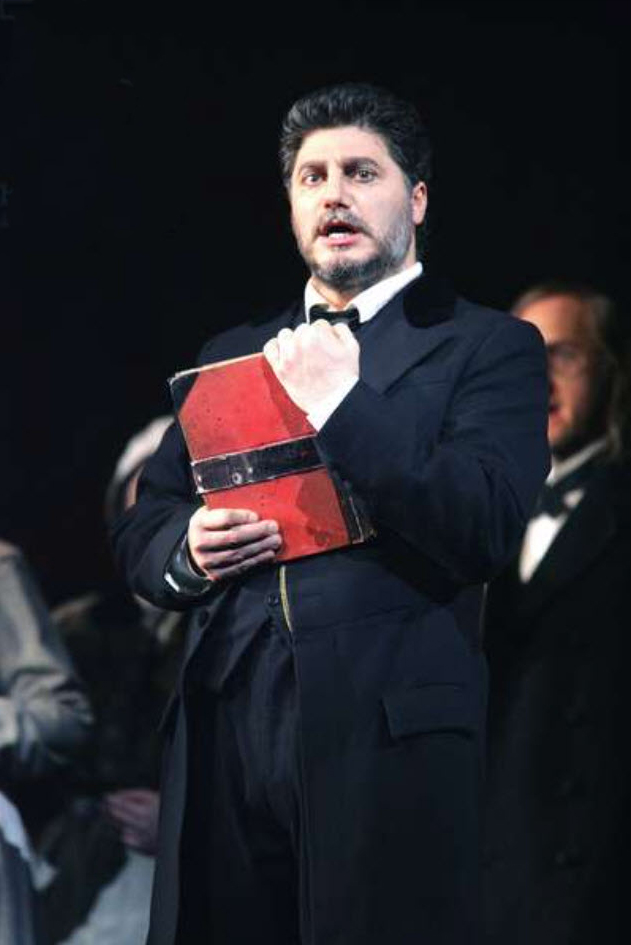

Stiffelio

Zurich 2004 / 2006

|

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “Stiffelio, whose exhausting tenor role outshines all others, at least in the ensembles, is subjected to an ordeal of extreme emotions right from the start, vacillating between manly jealousy on the one hand and pastoral mildness on the other. José Cura not only manages to take turns looking like Otello and Christ; his statuesque tenor voice, which is not entirely unchallenged in the upper register, has the necessary power of the one and the emotive sweetness of the other.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, September 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “[The cast] sing very well. José Cura, the highly acclaimed tenor, is primarily inspiring because of the way he sings. Very intense. Very emphatic. His tone itself cannot be called beautiful and at times it seems as if his deep chest register lacks a bit of overtones.” Südkurier, September 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “José Cura displays dramatic verve as Stiffelio, but is so vocally strained that almost all that can be heard is a pressed twang.” Basler Zeitung, 28 September 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “Tenor José Cura creates a strong vocal commitment as Stiffelio, a man who should be able to forgive his fellow man but in whom, instead, jealousy and anger boil ominously. His gaze remains fixed on the Bible at the very end, after Lina has been forgiven on a religious level, at the request "from above," through the mouth of the priest. Cura sings with an instrument capable of great power; occasionally the voice takes on a somewhat annoying nasal tinge.” Thurgauer Zeitung, 28 September 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “As Stiffelio, tenor José Cura demonstrates the full range of nuances from pastoral depth to ardent virility not only by being near-perfect in appearance, but also in voice.” Tagblatt der Stadt Zürich, 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “The Zurich Opera has had the good fortune to assemble a cast of stars. Granted, José Cura is certainly not the most rigorous of singers and he sometimes shows stylistic inconsistencies, but here we feel that he is very involved in his character, giving him great intensity. Certainly, his Stiffelio does not really appear to be beset by doubt; on the contrary he clearly favors revenge but he remains perfectly credible. Undoubtedly, the strong stage presence of the singer makes it possible to forget some imperfections, in particular a rather nasal emission, but overall the voice - which has become heavier - still seduces, with its baritone tones, its insolence in the high notes and its flexibility in the attacks.” ConcertoNet, September 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “In José Cura’s portrayal of Stiffelio, one can observe the conflict of emotions-a conflict between vindictiveness and reconciliation, worked out carefully by Verdi. Especially in the ‘piani’, Cura finds incredibly beautiful colors and a great vividness.” NZZ, 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “José Cura paints an immensely vivid and malleable picture of the protagonist, the pastor of a sect: (and he does so) with superb body control down to the fingertips and with differentiation in his musical character.” Der Landbote, 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “Stiffelio is at the center of the opera, sung superbly by José Cura. As an actor, the 38-year-old Argentine tenor has strong stage presence in personifying the inner conflicts of his character. From his dark tenor of almost baritonal timbre, he manages to elicit surprisingly velvety colors and shadings. In his strong emotional outbursts, Cura’s Stiffelio points toward Otello.” Neue Luzerner Zeitung, 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “Jose Cura as the cult leader Stiffelio is hardly believable in his transformation into a forgiving priest; he emphasizes the avenger too much early on. Vocally, too, he shapes the role as a veristic precursor: constantly under high pressure, sometimes chanted and with strangely colored vowels. Cura brings tremendous energy to the stage but leaves behind too much of the musical line.” St Gallen Tagblatt, 28 September 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “This role, in which (José Cura) made his debut at Covent Garden and attracted attention ten years ago, does not come across as unoriginal or exaggerated in any way. Cura is rather looking to emphasize the finer points, i.e. an inner drama—an intelligent portrayal.” TagesAnzeiger, 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “José Cura portrays this main character with a high degree of authenticity. And if he hadn’t sung so splendidly and used such an unbelievably easy and surely guided voice, if he hadn’t sung the high notes tied in so organically to the singing line, you could hate this uncontrollable, intemperate man. [Part of] Cura’s exceptional charm lies in his quite specific timbre. A tenor singing the role of priest is quite unusual, because these roles are usually reserved only for basses. But Stiffelio, a bundle of passionate temperament, simply has to be a tenor.” Opernglas, 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “Thanks to the stage presence of José Cura and Leo Nucci, at least two protagonists receive character traits but Reinaldo Macias as the seducer and Emily Magee as the seduced are helpless on stage. As a result, although the four protagonists hit Verdi's notes, musically the performance hits a dead end. José Cura’s personality is so great that it can also be called "behorsororiginell.” But the tenor, who takes pictures as well as conducts, keeps himself and his sometimes exuberant powers in check and sings quite passably. His voice, meanwhile, has the characteristics of a pair of old jeans: sometimes it seems cool, but on closer inspection one notices that the exposed parts have been patched up and that large parts have become colorless.” Aargauer Zeitung, 28 September 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “In this Zürich production, nobody –with one exception—found any really workable solutions to the challenges. The exception? His name is José Cura. The Argentine tenor was the only one who really breathed life into his character; the only one who was capable of creating intensity and credibility, of portraying a real human being with real conflicts.” Zürichsee Zeitung, 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “Two world stars - tenor José Cura and baritone Leo Nucci - save a weak opera by Giuseppe Verdi.” Blick, 28 September 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “A Zürich premiere: At the Opera House, Verdi’s Stiffelio was performed for the first time ever--a powerful opera, sung and enacted by strong singers of great renown....The delight of this production--awarded hearty and warm applause at the first performance--is that it gives wings to Verdi’s soul rather than turning out to be a cut and dry exercise in philology. With great, intense commitment both singing and acting, tenor José Cura offers up a Stiffelio who should be able to forgive another human being but who instead is boiling with jealousy and ire. At the very end, his eyes are still fixed on the Bible, staring at it, as Lina just at that very moment has been granted forgiveness “from above” on a religious level through the words of the preacher. Cura sings with a voice capable of developing and displaying immense power.” Thurgauer Zeitung, 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “José Cura, the Stiffelio, was the only member of the cast who had sung his role before. Verdi imagined that Stiffelio would sound like "a great silver plate struck with a silver hammer"; Cura's timbre is more akin to a bronze tocsin. He has a visceral, chest-oriented ferocity, and there is certainly no lack of heft or vigor to his sound. One could wish for more subtlety in his delivery of the words and a smoother spinning of the musical lines, but his delineation of the character's dilemma, torn between his fundamentalist morals and his intense sexual jealousy, was very impressive indeed. Some Stiffelios I have seen in previous productions could not escape a certain sanctimony; Cura created an unusual and most effective character with his almost unbridled sexiness. Lina must have been desperately frustrated by this Stiffelio's absence to have fallen for the bland playboy charms of Raffaele.” Opera News, December 2004

Stiffelio, Zürich, September 2004: “The Stiffelio by José Cura stresses the avenger. Vocally he images the role as a precursor of Verismo: constant and high pressure even during the quiet moments, often sung with strangely discolored vowels. Cura brings such tremendous energy on stage but he remains guilty regarding the musical line.” ZO, 28 September 2004

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Click on any of the photos above for short videos from the Zurich 2006 production of Stiffelio

|

||

|

|

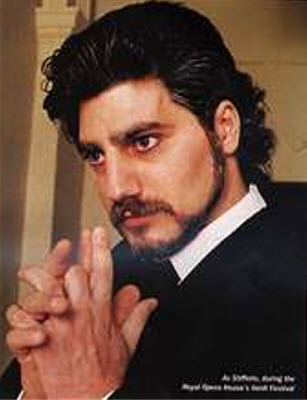

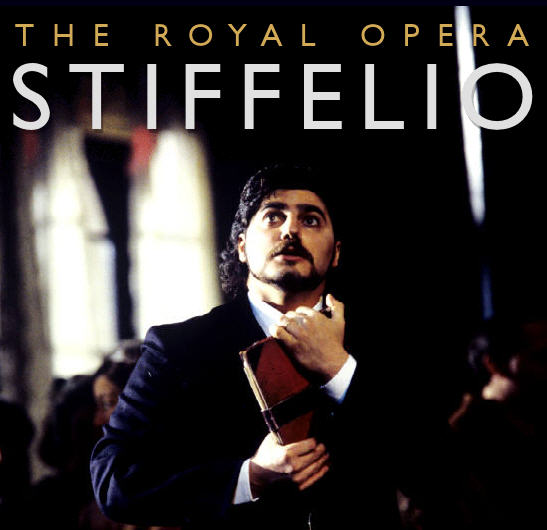

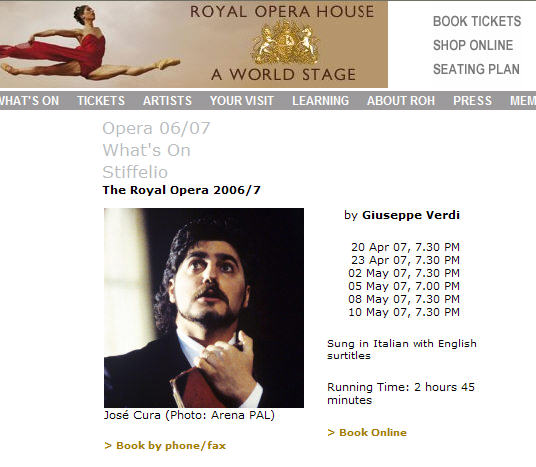

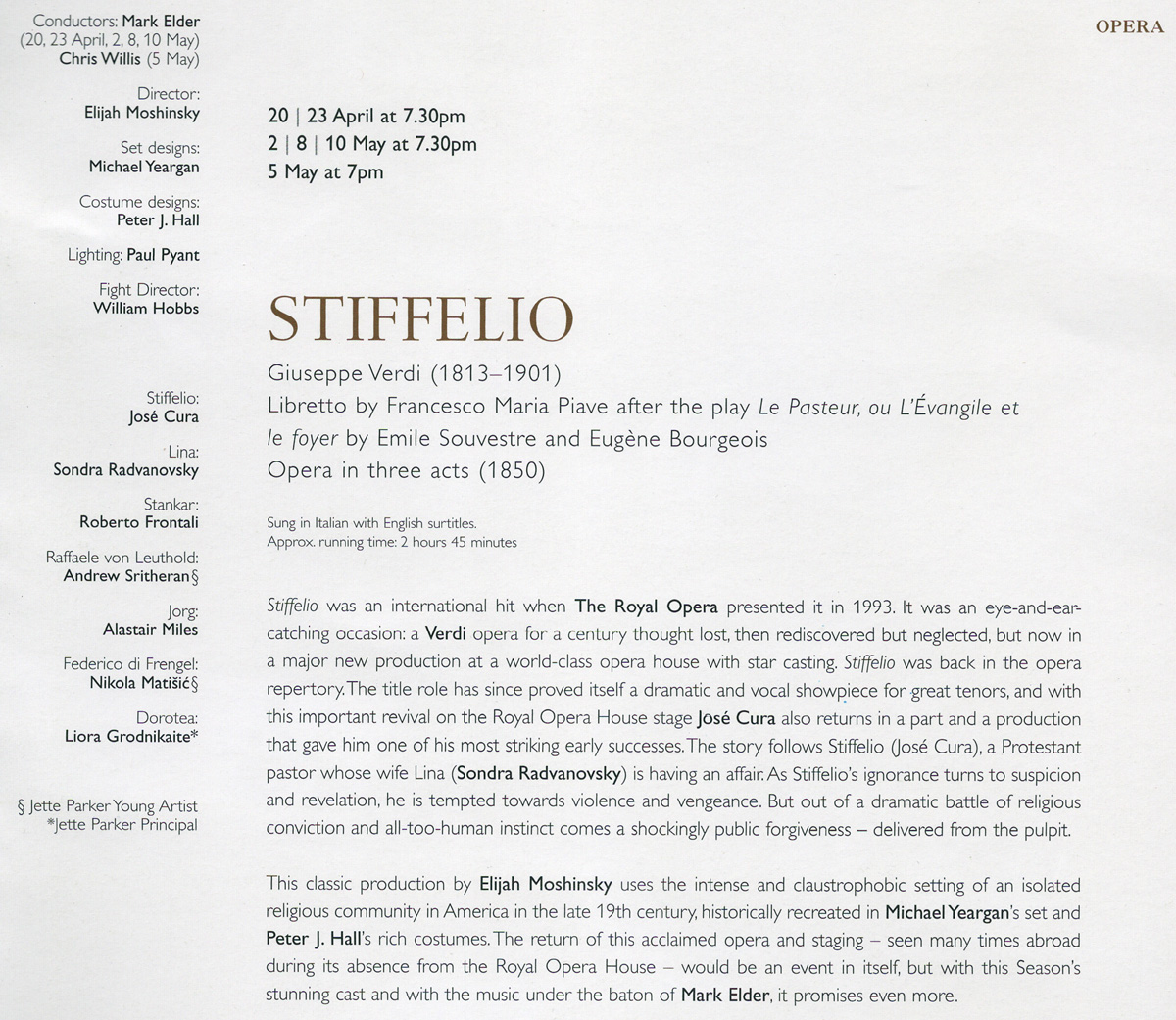

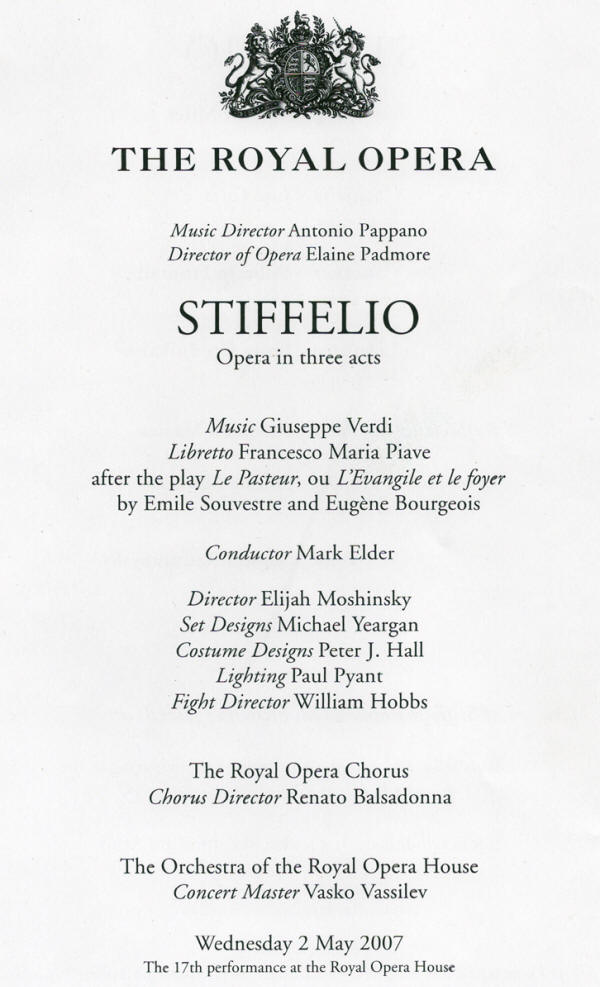

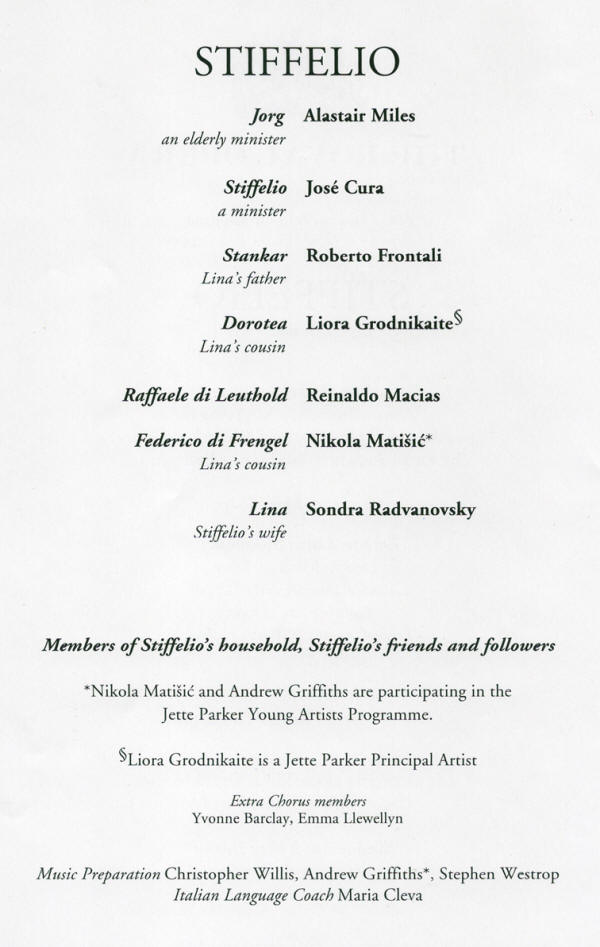

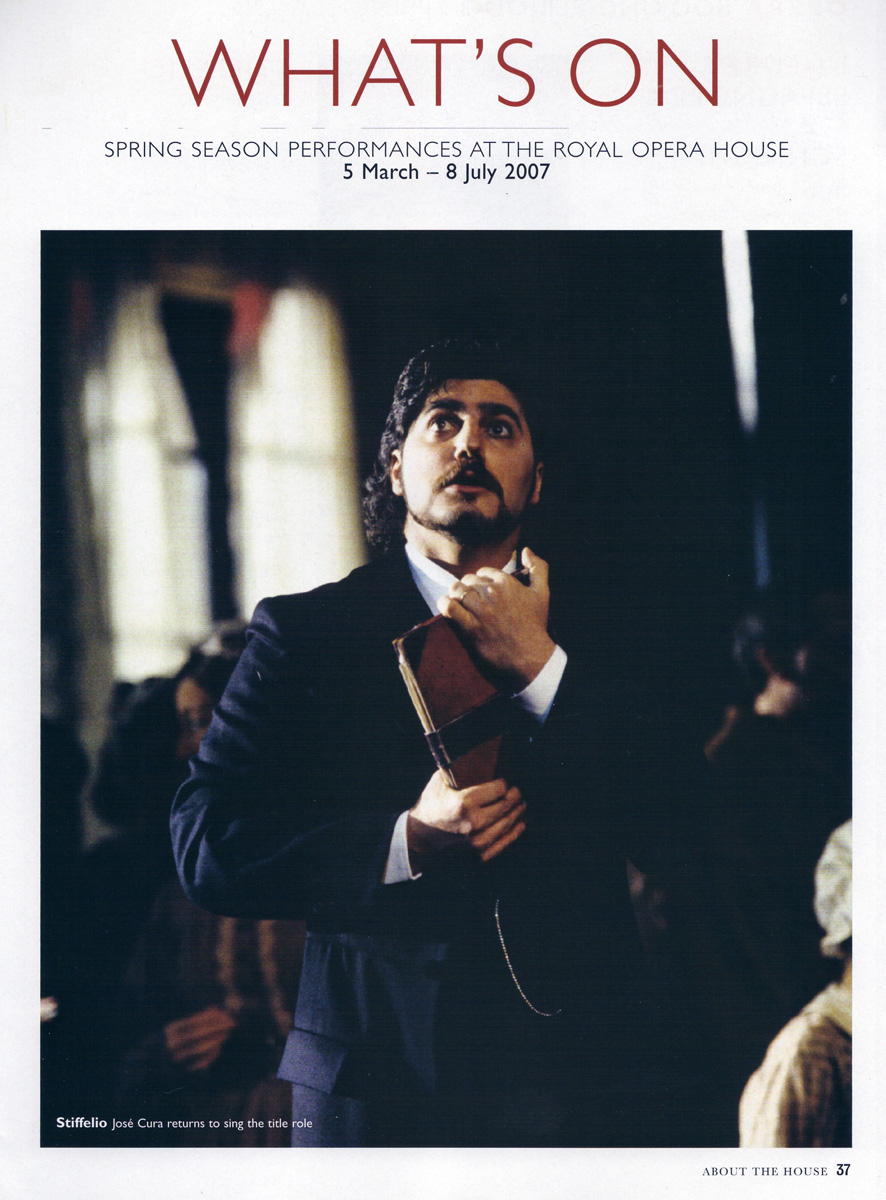

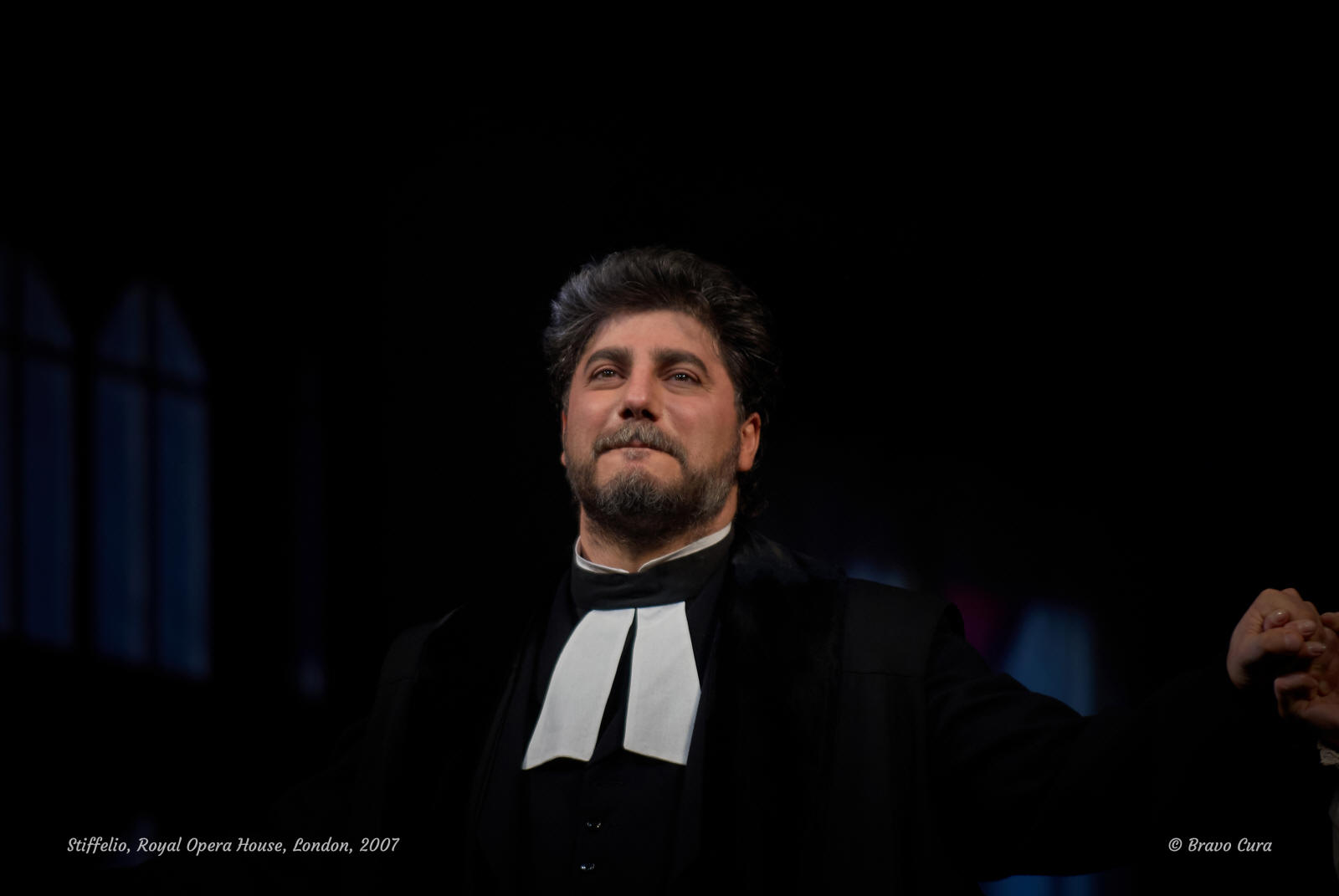

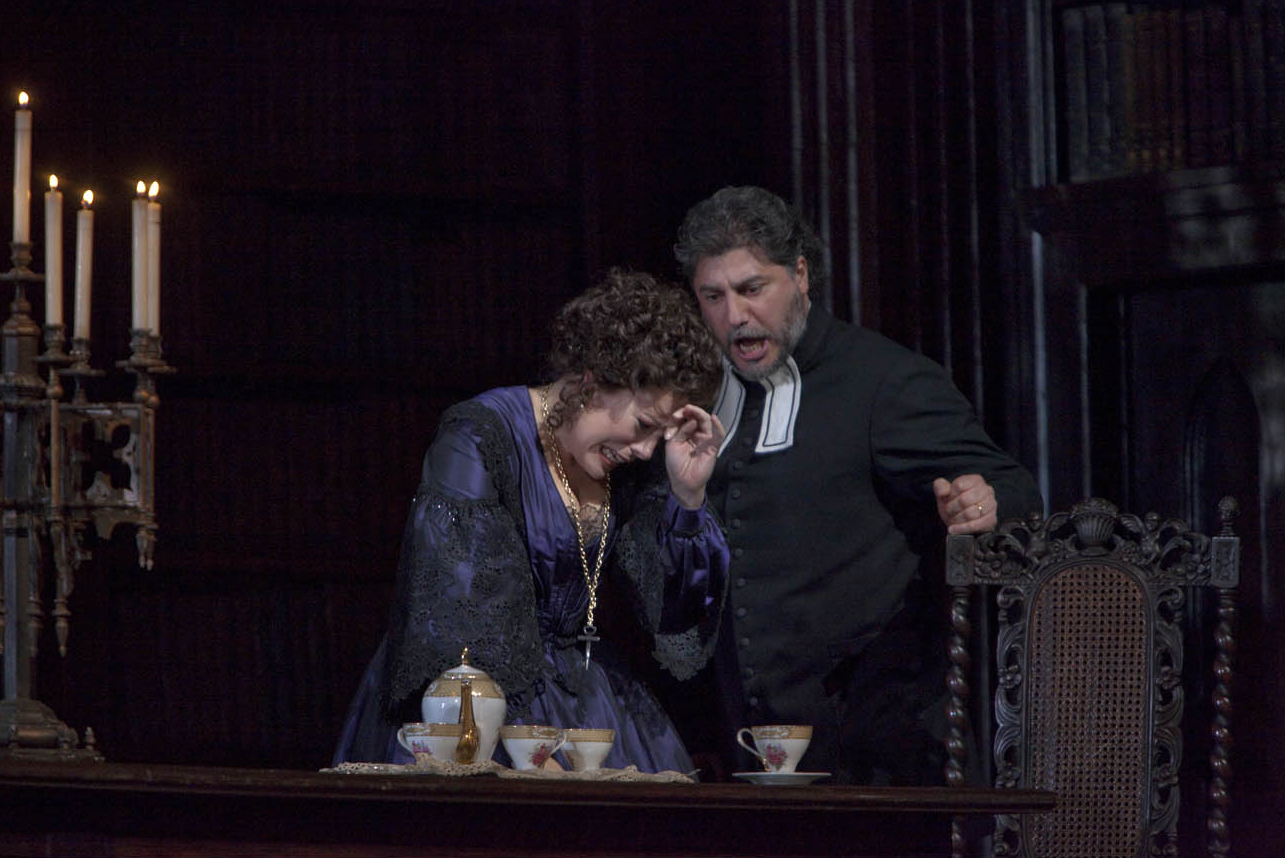

Stiffelio

Covent Garden 2007

|

|

Covent Garden - 2007

|

|

|

Reviews

|

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “The first act seemed a particular challenge to José Cura in the title role. In his short aria of the boatman, the ensuing concertato and in his duet with Lina, Cura had a tendency to push his voice, with the effect that he sometimes lost accurate tuning and, in particular, he kept missing rests or proceeding too quickly through notes so that conductor Mark Elder and the orchestra had a hard job of keeping up. After the interval, however, Cura seemed more at ease. His tone was more exciting in the graveyard scene, and both of the final scenes were deeply moving; his acting was unflaggingly dedicated throughout. I would strongly recommend this rare opportunity to hear one of Verdi’s most modern and unjustly neglected works onstage at Covent Garden. ” Musical Criticism, 20 April 2007

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “Handsome and swaggering, Cura gives a barnstorming performance with a return to the thrilling vocal form which made him famous. The difficulty is that you cannot believe in his inner religious faith. He excels at intensity, but not humility. When finally, with much furious Bible bashing, he forgives Lina you fear for her safety the minute the curtain goes down. …” Evening Standard, 23 April 2007

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “José Cura keeps his extrovert-self contained, but you can see how Stiffelio is boiling inside…” Classical Source, 20 April 2007

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “The dark, Latinate tenor Jose Cura brings a note of beefy charisma to the title role. His top notes might not be as lustrous as I've heard in the past and he overacts on a couple of occasions, yet he keeps a cool check on his glottal swoops and vocal mannerisms, and the result is exciting.” China Post / Bloomberg, 24 April 2007

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “José Cura, in the title role, sounds tight and technically edgy.” Financial Times, 23 April 2007

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “José Cura's glassy eyed stare at the work's conclusion made no promises for the future of the relationship, and it made a lot of sense after the tenor's emotionally giving performance. Stiffelio's animalistic, Otello-like rage was kept firmly under lock and key, and when it did burst forth, it did so with venomous fury. Vocally, Cura's inhumanly baritonal tenor was deployed with a manner standing somewhere between good and bad taste. I could have done with a tad less barking in Act One but, in Act Three, Cura found a noble and exciting ring up above.” Music OMH, April 2007

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “In his first appearance on stage, José Cura did not pay much attention to Elder’s baton, nor did he convey any emotions with his static acting and monotonous singing. Things improved as the tamer’s whip, the orchestra, imposed its rule and made the singer follow them. Cura’s loud wilderness lost its worse side, and from act two on he sounded increasingly passionate and at the same time more controlled. I still think Cura is not the most exciting singer, but his acting has improved a lot in the last three or four years. It is in operas such as Stiffelio and La Fanciulla del West in which this improvement is more apparent.” Mundoclasico, 27 April 2007

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “The crucial shortcoming is José Cura in the title-role. Apart from a little pianissimo crooning, he seems able to produce only a harsh and effortful forte, much of it sliding under the note. He makes nothing of the text, goes his own sweet way with tempi, and despite his swashbuckling appearance, achieves no convincing characterisation. What a sad collapse of a once promising tenorial contender.” Telegraph, 23 April 2007

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “Twelve years on, its latest revival effectively allows Cura to return to the role that made him famous. Time has taken its toll on his voice, though his performance remains compelling in its erratic brilliance. His carnal presence offsets the fiery, eruptive fanaticism that glows in his eyes. Faced with this conflicted creature, you understand why Lina (Sondra Radvanovsky) has sought sexual happiness elsewhere yet remains emotionally attached. Occasionally, he phrases clumsily, but there are also moments of hushed introversion.” Guardian, April 2007

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “José Cura [is] a tower of strength as the preacher Stiffelio.” The Stage, 23 April 2007

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “For its revival of Verdi’s ‘lost’ masterpiece, the Royal Opera fields what must be three of the most turbo-charged voices on the planet. Every note of Verdi’s electrifying vocal writing comes over loud and clear. José Cura [is] the anguished preacher Stiffelio…” TimeOnLine, 23 April 2007

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “Rather more disturbing in the case of Jose Cura in the title role was a complete disregard for Verdian line. For a singer who fancies himself as a composer and conductor, his sense of rhythm is disgracefully wayward. Elder had his work cut out keeping him on track. It isn't Cura's fault that he is infinitely more attractive than his on-stage rival Raffaele (Reinaldo Macias), and those dark, swarthy looks with a voice colour to match will always be seductive to audiences. But he is a poor singer with only vocal brawn and the basics in tenorial histrionics to carry his message to the back of the auditorium. Whatever happened to phrasing, to legato? More and more, too, Cura is developing two voices: it's like he's going from automatic transmission to shift-stick between craggy baritone and dramatic tenor.” Independent, April 2007

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “For me it continues to be Verdi’s realisation of the main characters that is the main reason to experience Stiffelio. José Cura previously took the title role at Covent Garden in 1995, but the intervening years have seen his voice change considerably. Arguably he no longer has what many would consider a typical star tenor’s voice, if such a thing exists; for his is now darker in timbre, appreciably more comfortable in the middle and lower ranges, though not without reach to the top when required. Coping with the challenges such change throws up can make an artist out of a musician. His phrasing is still sensitively timed and weighted, and his long experience in the Verdian repertoire pays dividends in that respect too. If early on in the evening an occasional hollowness of tone induced slight doubts as to his vocal form, these were more than offset by the dramatic benefits to be reaped in his later prolonged scenes of doubt, anguish and soul-searching. That his tone could be none other than it was gave credibility to thought, action and plot that could hardly be manufactured. Stiffelio sees the Royal Opera back on peak form. That this cast and company has a very special relationship with the work cannot be denied.” Seen and Heard Opera, April 2007

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “A decade on, Cura is back in this rather thankless part, flinging his arms around in a display of operatic acting so antique as almost to acknowledge that other tenors have since dimmed his once shining star. His voice is as strident as ever, lacking the expressive subtlety such a role demands…” Observer, 29 April

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “In the title role, José Cura, the Argentinian tenor, is surprisingly convincing. Better known in the roles of handsome seducers himself (he last appeared at Covent Garden as the outlaw Dick Johnson) he here conveys both the gravitas and despair of a pastor whose world is falling apart. Even the way in which he slowly and repeatedly takes his spectacles on and off, shows his pain – they seem heavy as lead. Cura’s immediately recognizable, burnished tenor is made for this role and he shines in it.” The Baptist Times, 26 April 2007

Stiffelio, London, April 2007: “Cura cannot match [his predecessor] either in his portrayal of the character or in the grace and elegance of his singing. When he remembers to sing below forte he is quite agreeable, but his tone is course (to my ears) and often forced.” Opera, June 2007 |

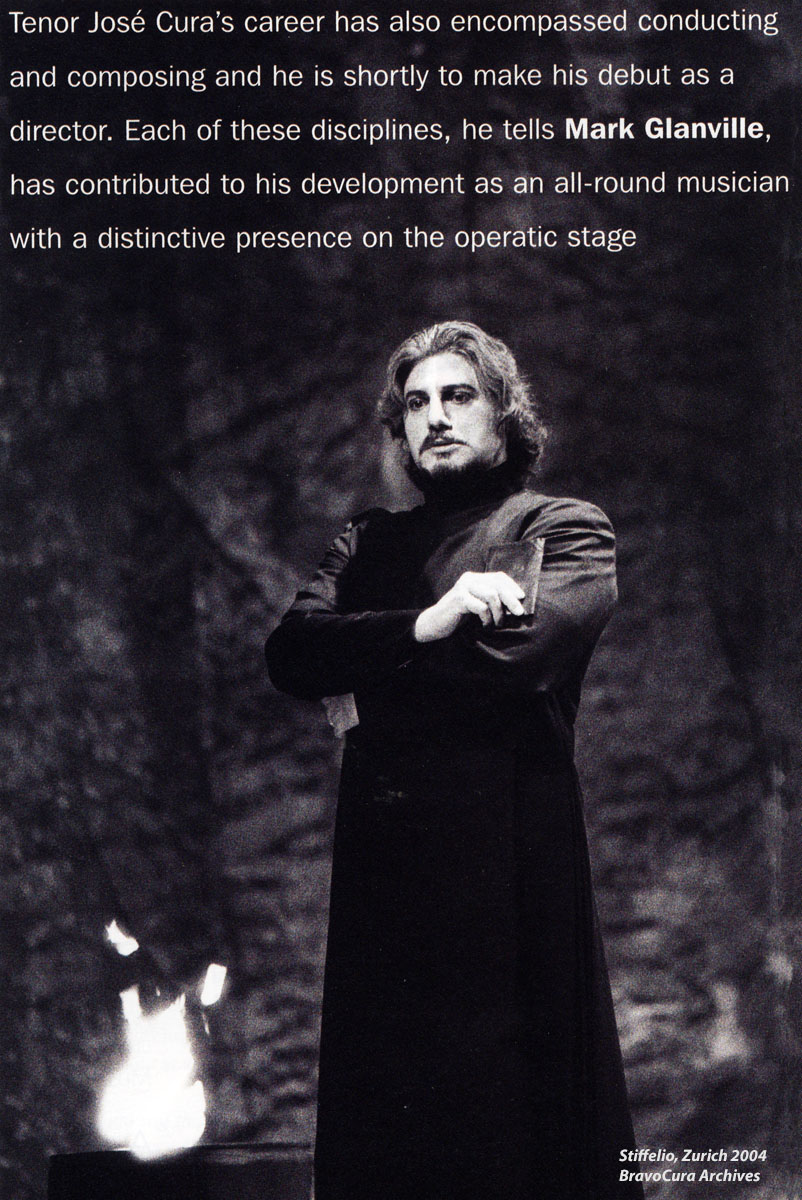

Articles

|

José Cura: 'I have always been an artist who was ready to put his head on the block.' Interview on singing on Stiffelio at the Royal Opera House and his ambition to play Peter Grimes Musical Criticism Dominic McHugh 2 April 2007

Almost exactly twelve years ago, a young and largely unknown Argentinean tenor opened the Royal Opera's Verdi Festival playing the title role in Stiffelio, Verdi's long-neglected masterpiece of 1850. But in the interim, José Cura has risen to become one of the most highly-acclaimed and beloved singers of his generation; at Covent Garden, he has performed leading roles in operas such as Samson et Dalila, Il trovatore, Andrea Chénier and most recently La fanciulla del West. He returns to the House on 20 April to bring a fresh take on Stiffelio, and I caught up with him in the middle of a heavy rehearsal schedule to see what his views on the piece are. Although it's often been overlooked, Verdi took many risks in making an opera out of Stiffelio, because the story is riddled with controversial topics. A pastor's wife commits adultery; the pastor challenges his wife's lover to a duel; she asks him to hear her confession as a minister; and in the climactic final scene, Stiffelio reads a story from the Bible to publicly forgive her (some of the early productions cut this passage because it was considered a scandalous use of a religious text onstage). I ask Cura whether this kind of daring and danger characterises him as an artist as well. 'Well, it's a different kind of daring!' he laughs. 'After having been happily married for more than twenty-one years, it's not the kind of threat that endangers my life. But yes, daring in the sense that I have always been an artist who was ready to put his head on the block, ready not to be too obvious. For that reason, as you know, I have been praised, and I have been criticised. That's fine. It's a good sign.' Cura is a very complete musician: he has been a conductor even longer than he's been a singer, he is an intelligent actor, he evidently understands music from the inside as well as the outside. Is that the key to his success as a singer? 'It is an ingredient, yes. But I think the key ingredient is to be daring enough to use all this information. I don't think I'm the first or the last singer to have this kind of complete approach to the business. That's something called professionalism, and we expect more and more people to have it. But what is rare is to use that encyclopaedic information in the complete sense: not merely to know it - because as I've always said, for as much as one person knows about something, there's always somebody else who knows more - but actually to use that background as well. Show it! It's a case of having the courage to go onstage and say 'I have discovered this and this and this and I am bringing it to you' rather than 'I have discovered these things but because I know what I have discovered it is not what you expect me to do, to avoid any danger I will not show it to you'. That has never been my philosophy.' His debut as Stiffelio at Covent Garden in 1995 evidently holds many memories for him. 'One of the main things that I remember is quite funny, though the meaning is not so funny. At that time, in order to get me to look older they had to colour my hair and my beard white. Now I don't need to because I have enough white of my own! It means I have a completely different approach to life - experience and maturity as a human being, which is perfect for this role. 'This is a completely different take on Stiffelio. Many roles don't need that kind of thing - they need maturity as a musician but they don't change a lot as you mature as a human being. But Stiffelio is one of those roles like Otello, where age and experience of life changes your approach to a part, to the meaning of a word, to the psychology of the character.' Written in 1850, Stiffelio comes before three operas which are often (though erroneously) considered to belong together as a trio: Rigoletto (1851), Il trovatore (1853) and La traviata (1853). Does Cura think it deserves to be elevated to the same sort of 'masterwork' status? 'It depends on your point of view, of course. For me as an interpreter and an artist, yes, I consider it to be a masterpiece. But if to consider an opera a masterpiece you need to have fifteen minutes of recognisable tunes that become hits, then of course it's not that kind of piece. You do not have 'Nessun dorma' or 'Di quella pira' here. In terms of musical style, it is a piece conceived more like Peter Grimes. The music leads the action, one behind the other; apart from a moment in the third act when the baritone has a big aria and stops for a moment for the 'picture' and then goes on, it's music that drives on from beginning to end. It's like an Ibsen play. It's a raw drama.' What does he make of the character of Stiffelio? 'The character is so complex and so psychologically linked to every other character on stage (unlike Calaf in Turandot, for example, who is the same all the way through) that I'd rather say what we are making of the character. What we are doing with him is the result of reading what my colleagues are making of their own roles, and to that extent I think what we're creating is very strong. Today we spent six hours working on the tougher spiritual moments of the opera and we've discovered each other crying more than once. So we're going very deep with this. Everybody in the cast is inhabiting his or her role, not just singing the notes. I think it's going to be a surprise because what's going on now is very essential, in the pure sense of the word. We're doing very little on stage, moving only when absolutely necessary. Everything is passing through the text into our internal feelings and emotions. That's a big risk on one level because the theatre is big and it could easily be lost. But I think it's a good way of building up the opera at the moment - probably when we get onstage we'll make it a bit bigger so that it can be understood by everybody at a distance as well.' Mark Elder is the conductor for the current revival of Stiffelio and Cura explains how they haven't seen each other since he last sang Stiffelio here. 'In 1995 the conductor was Edward Downes. One month after that, I did the original 1857 version of Simon Boccanegra with Mark Elder. But since then, we've never worked together, so it's funny that we should meet up twelve years later to work on the piece that I was singing when I first met him. It's great to finally see him again after we've grown up together in such a parallel way.' We move on to more general questions, and I ask Cura what music means to him: is it just a career or something more? 'Oh, that's a very Freudian question! We could go on for ages and I'm not sure I want you to know what music means to me! With such a question you can become very kitsch or you can become very philosophical. Or I could be very practical, and say that music is a way of earning my living, which is true - it's a marvelous way of earning my living which I'm very grateful for; I truly and humbly believe I'm gifted for it and am glad I am able to do it. 'But parallel to that, I am like many musicians in being an enormous lover of silence. Most of the music in my life is linked to my professional activities; when I am not doing music as a professional, I am normally in silence. So today I cannot say that music is the essence of my life or that I listen to music from the shower to the bed. Music is a beautiful business and I'm lucky to do something so great, but I really appreciate silence.' Does he like working at Covent Garden? 'Yes, I wish I worked more here, and I don't say that because I'm an easygoing flatterer! This is probably today the number one house in the world. It's not just a single aspect that's great but all the departments work perfectly together. Of course if you are inside every day you get to know all the tiny problems, but in a house things are never going to be always perfect. It's the result of the whole thing that makes this house very special. 'You have the luxury of not working in a repertory system. That means that each opera is taken one at a time and built. So each time something goes on stage at the Royal Opera House, we know that it's the best we can possibly do at that time. That's a great thing. In a business that's getting more and more superficial and commercial and 'fast', it's wonderful to have three weeks of rehearsals for a revival like this, for example. Personally, I'm not usually fond of doing many rehearsals unless we're doing good work that justifies the time, but I'm having the time of my life in this case. I'm the first one to arrive and the last one to leave! I'm really having a great time.' He admires the audience here, too, which he feels is very much based in a serious theatrical tradition: 'There's a theatre every 100 yards in London. You can really tell that when you're approaching an opera with dramatic truth, it's being appreciated. In some other places, they expect you to stand around like some singer from the 1950s, so there's a very different characteristic of working here.' Any plans to return? 'Next year in September we're doing La fanciulla del West again because everyone enjoyed it so much - it's a fabulous piece and a great production. And in December 2008 I'm singing Turandot - my first Calaf in the UK. But beyond that, there are no more projects booked, so I hope that before I leave we can plan something.' And what lies ahead for the singer, given that he's already sung most of the major roles in the Italian repertoire - anything new? 'That's a good point, because it's very difficult to persuade opera houses to go for new repertoire. Being mainly specialized in dramatic roles, when you have a free period the opera houses want to go for a Samson or an Otello - works that are very difficult to stage because so few people can do them. So it's difficult to say 'I have one month free, can we do Le Cid?'. But one of my dreams is to do Peter Grimes and I would love to do it here. Where better to learn and perform it than here in London? On the other hand, it's a very dangerous thing to do. If you do an English or German opera and you are not English or German and don't get the accent absolutely spot on, you are criticized to death. But if you're English and you sing an Italian opera without a perfect accent, nobody says a thing. I don't know why it works like that. I think that the Italian approach is the most healthy because it's not possible to have a perfect accent in a foreign language, but who cares if I speak English like a Spaniard? The important thing is to have a perfect approach to the characterisation. I think I could do Peter Grimes, but every time I suggest doing it in the UK they say 'yes, but go and do it somewhere else first and then bring it here'. Why?! I want to learn it well from the beginning rather than do it again and have to start from scratch. Hopefully someone will read this and allow me to do it!' He also seems keen on the idea of having an opera written for him: 'That would be great - if you know somebody, just pass on the word!' While he's in Britain, Cura is busy spending time on helping young singers. On 4 May, he's chairing the panel of judges for Opera Rara's bel canto competition at the Royal Academy of Music, while on 6 and 7 May he is taking part in a masterclass with twelve young singers at New Devon Opera, of which he is Patron. 'For me, this is one of the most important things. It's something I didn't have when I was a kid. It's essential to share with young people all the things you learn as well as hearing from older people all the things they've experienced; it's about growing up together. It can be amazing: you attend a masterclass for two hours and you end up spending ten hours with them and you don't know how it happened! It's great, provided that there's preparation and respect. I always tell them I'm not there to teach them how to sing - I don't have the technical authority to tell someone how to do that. But I want to bring to them some things I know from my own experience. 'Young people like you are everything to the future of opera. I'm only 44, so I'm not the past! But if I'm the future for the next twenty years, you are the future for the next forty years. And the people behind you will be the future for the next sixty years. If there's hope for everything in the world, the hope is in the future, not in the past. Once I read a quote that said, 'Children are the living messages of the future you are not going to see'. That's so absolutely true: it's the future of humanity.' |

Classic FM

Sarah Kirkup

You're the patron of New Devon Opera... Why do you want to help? You're in Stiffelio at Covent Garden from 20th

April... Acting's important to you... You conduct as well... What's your next ambition? |

|

The Latest Challenge for José Cura Heraldo / La Nacion / Terra April 2007

|

|

Preview: Stiffelio, Royal Opera House, London He can't be the same man, can he? Independent Michael Church 12 April 2007 In 1993, José Carreras celebrated his triumph over leukaemia by starring in Verdi's Stiffelio at Covent Garden. Two years later, an unknown singer named José Cura replaced him. That was Cura's launch: overnight he was awarded a big recording contract, and hailed as the "fourth tenor" and as a new operatic sex symbol, and his meteoric career began. Now he is back in that role: the production is physically the same, but since both he and director Elijah Moshinsky have changed in the intervening time, it will also reflect that. "Then I was a naive young kid trying to fit into the shoes of a tormented and complicated adult," says Cura. "Now I am closer to that character." Is his voice changing? "A lot. It's getting darker and darker, to a point where some people think it's moving beyond the tenor range. Certain characters I cannot do now, not because I can't, but because the colour of the voice wouldn't portray the psychology." And although he still exudes the lazy pantherish charm that made his first interviewers go down like ninepins, he's taken drastic steps to obliterate that original image. "All that stuff about the sonny-boy sex symbol, those stories about the fourth tenor - it was sending out the wrong signals, and I was getting shot at with the wrong weapons. I grew very unhappy with how I was being sold, so I dismissed my agent and set up my own company to organise my work. "I'm 44, and I started my career when I was 14 - I've worked very hard to become a serious musician and a finished artist, and now we've cleaned away the garbage. Now I am accepted as serious artist." He globetrots as a conductor as well as singer, he's staging his own touring production of Pagliacci in Croatia, and he has had a new CD and two DVDs out in the past three months: point made, point taken.

|

Production

|

Our Photos

|

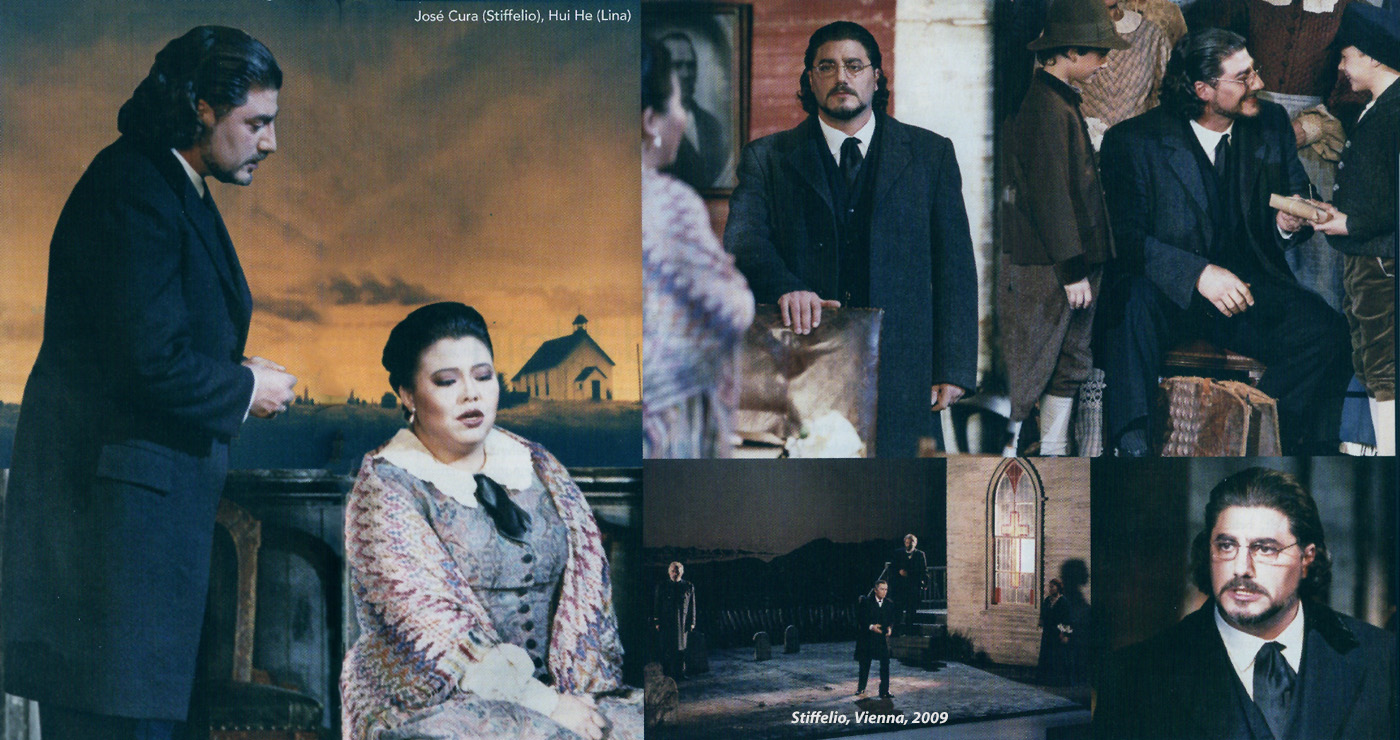

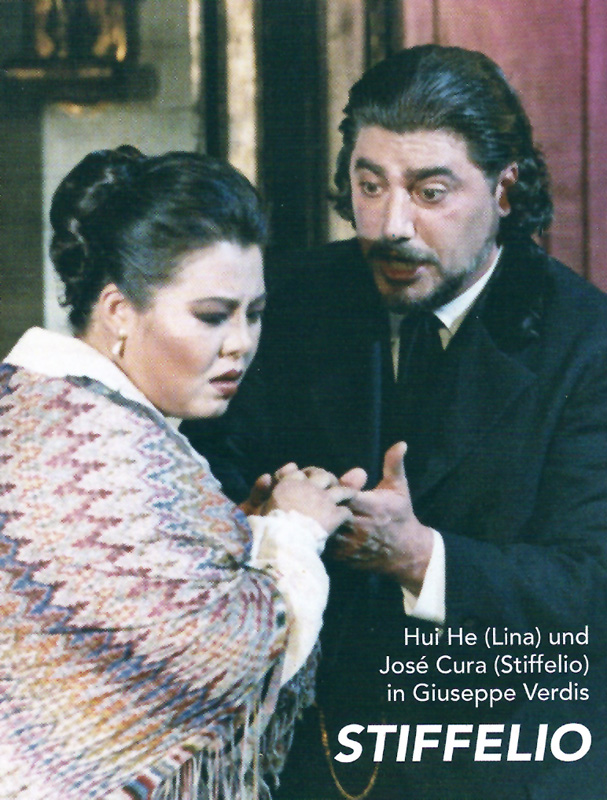

Stiffelio - Vienna - 2009

|

Stiffelio, Vienna, February 2009: “With distinctive baritone and manly roughness in the low [notes] and with lots of strange sounding tones in the high, José Cura appeared as the preacher who was cheated on. Those who do not like him will always knock the effusive style of his singing while those who like him can almost always take pleasure in his intense singing and acting portrait in the role, as happened this evening when he thanked with much applause. To try to bind Cura to a bel canto song line would require a renunciation of intensity and expression.” Der Neue Merkur, February 2009

Stiffelio, Vienna, February 2009: “Star tenor José Cura interpreted the title character with increasing fervor and vocal power. He formed a credible, multi-faceted character.” Wiener Zeitung, 11 February 2009

Stiffelio, Vienna, February 2009: “The hapless man of God, Stiffelio, arrived (as in the last few years) with José Cura and it is certainly one of his best roles - he does not do much yet conveys the internal struggles credibly. Vocally, we have heard the same for some time: passages with real, beautiful tenorial brilliance - and all too many in which he audibly does not control his voice. Applause.” Der Neue Merkur, February 2009

Stiffelio, Vienna, February 2009: “While he maintains an active schedule as both singer and conductor in Europe, José Cura remains curiously absent from North American rosters. (He adds a quartet of Turiddus and Canios in March and April to the scant fifteen Met performances he has given over the past decade.) Stiffelio is a superstar tenor's opera, and Cura has the power, passion, dedication and sheer charisma to pull off a role that is not first-rate Verdi. At forty-six, he can boast a voice in spectacular shape; the slight huskiness that drifts in under pressure in dramatic passages is easily forgiven as an exchange for the moment. There is a ping, a squillo to this big, burnished trumpet of a voice that remains virtually unmatched for sheer tenorial excitement. Michael Halász occasionally stumbled with rhythmically-complicated passages, failing to make a case for this rarity except as a vehicle for the likes of Cura.’ Opera News, 7 February 2009

Stiffelio, Vienna, February 2009: “For José Cura (who also sings Don José in Carmen from February 25) the role of the sectarian priest Stiffelio is an ideal one: he perfectly displays the warmth of a religious leader at the beginning, later the despair during his budding jealousy and the rage of the offended man. Throughout, Cura is always Cura, an extraordinary figure and a unique personality. In that he outshines most of his tenor colleagues. Cura not only portrays his character with great sensitivity for human emotions, he obviously also feels them himself! And he convinces vocally, creates nuances and moods with his dark tenor voice; equally convincing his art of expression and phrasing. His wife Lina’s brief affair provokes in this brooding missionary a range of emotions far from pious, even a desire to fight a duel with his rival Raffaele. Ovations!” Wiener Zeitung, 11 February 2009

|

|

|

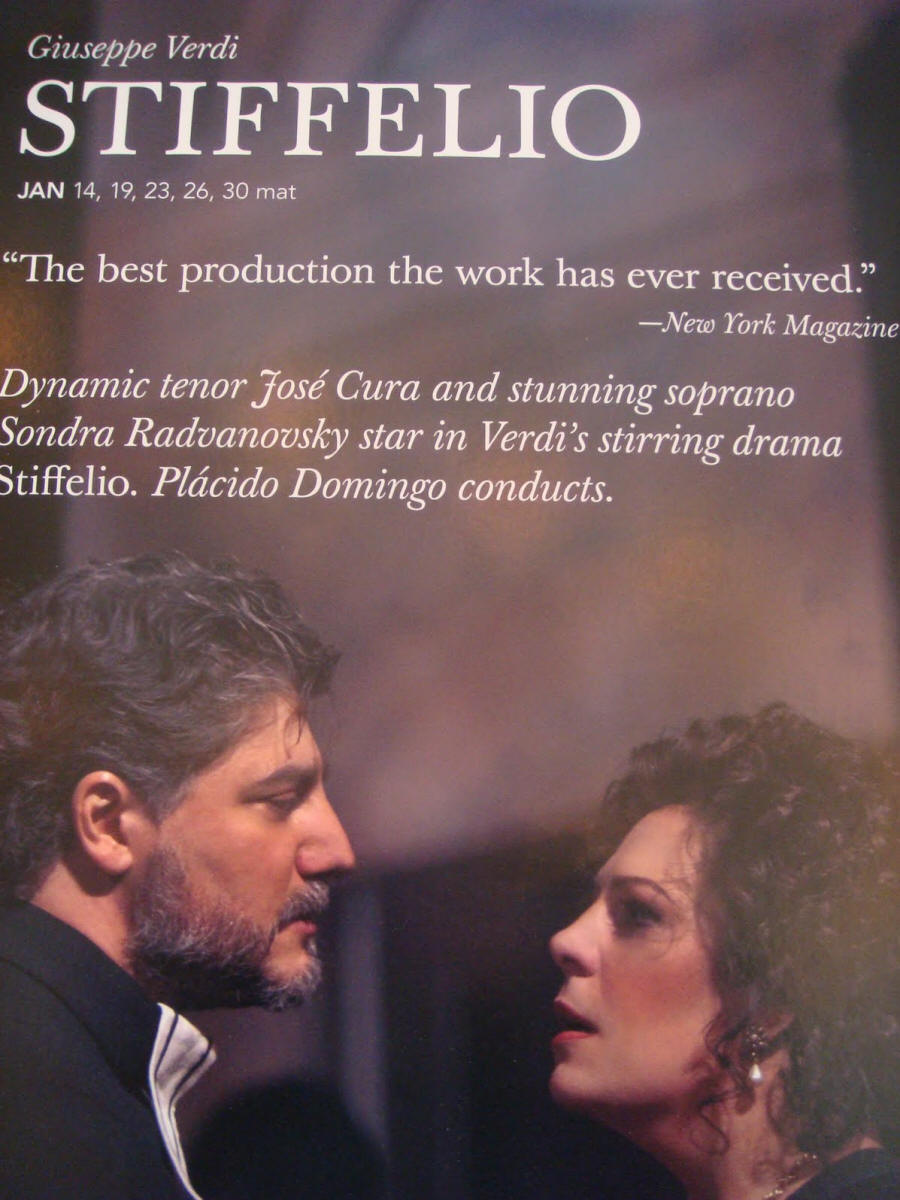

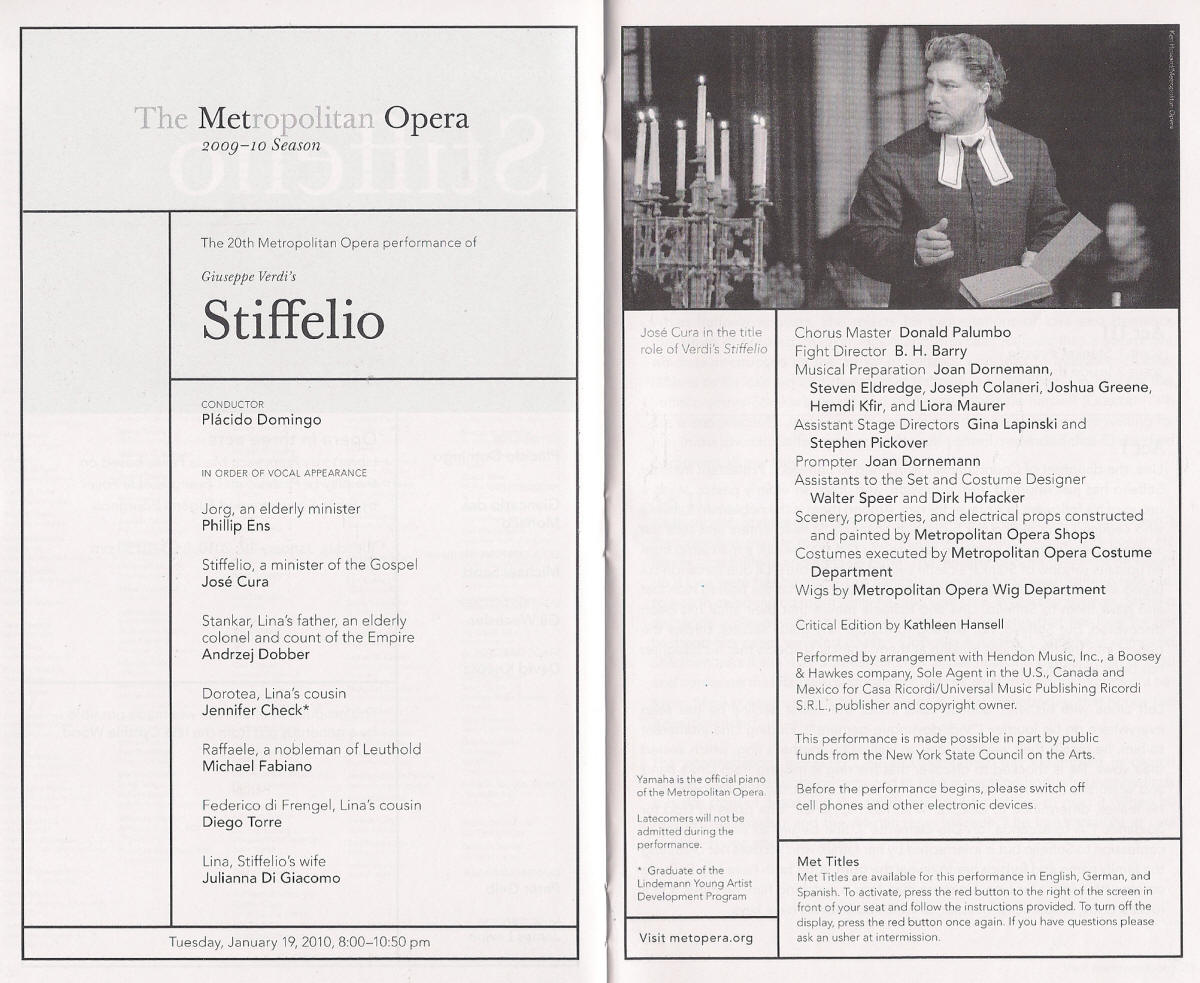

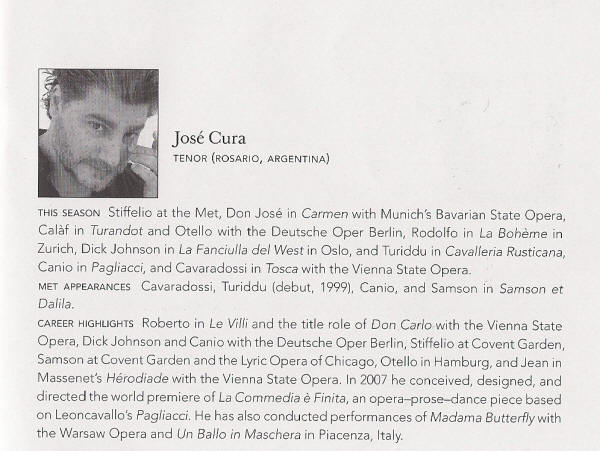

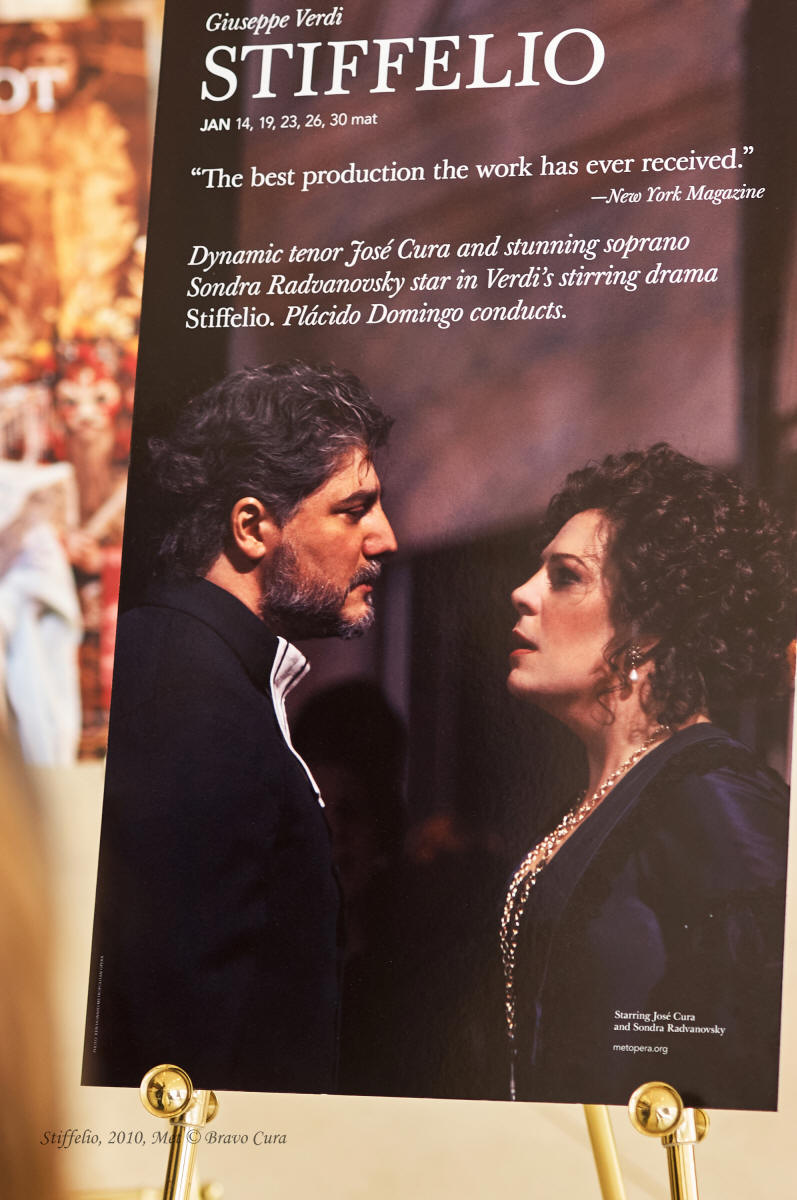

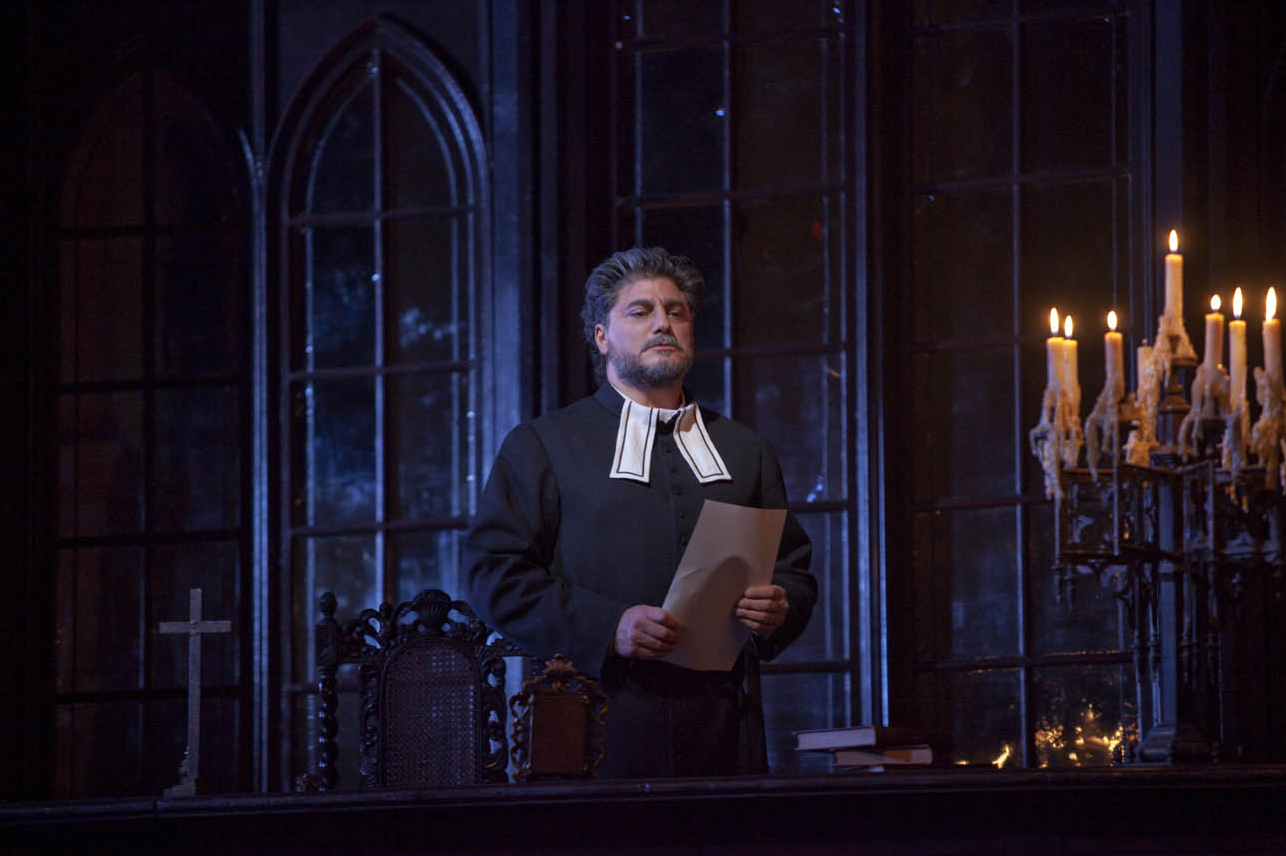

Stiffelio

Metropolitan Opera - New York

January 2010

|

Stiffelio, Met, January 2010: “The Met put together an exceptional cast to make a case for this unjustly neglected work. In the title role José Cura conveyed the minister’s emotional anguish with deep poignancy. From the brilliance of the restoration of the score to the overwhelming power of the singing, Stiffelio is an especially impressive triumph for the Met.” New York Daily News, 12 January 2010

Stiffelio, Met, January 2010: “Stiffelio itself comes off remarkably well. I don’t remember being nearly as taken with it when the production was new in 1993 but now it seems like time extremely well spent. The title role’s piety doesn’t exactly harness Cura’s sex appeal, and vocally he has reestablished himself as a major Verdi tenor.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 13 January 2010

Stiffelio, Met, January 2010: “[Plácido Domingo] didn’t quite sink Stiffelio with conducting that has progressed over the years from vague to basically okay. Giancarlo Del Monaco’s elegantly lugubrious production is back, and this time the role of the cuckolded reverend went to José Cura, who covered himself with respectability, if not quite with glory. Sondra Radvanovsky sang the role of Stiffelio’s wife Lina with irresistible rawness, alchemizing vocal iffiness into fierce intensity.” New York Magazine, 19 January 2010

Stiffelio, Met, January 2010: “José Cura played the title role with understated grief and was certainly more than reasonable.” Out West Arts, 25 January 2010

Stiffelio, Met, January 2010: “Stiffelio” is a drama of internalized conflicts and emotion. Mr. Cura has made his name with vocally raw, vehement portrayals of hotheads, especially Otello and Samson. Here he tried to convey the solemnity of this minister, seething inside over his wife’s betrayal. In bringing restraint and finesse to his singing, he sometimes let the energy drain away. At its best, his performance had flashes of vocal charisma. Still, I wish he had made more of the vocal and emotional similarities between this role and Otello.” New York Times, 12 January 2010

Stiffelio, Met, January 2010: “In the role of the tormented pastor, José Cura is a kind of rough diamond: full of unevenness, rough, wild, he has an electric presence but does not seem to completely master his brilliance. The result is an incandescent but undisciplined singing, a raw energy not always well channeled that surprises as much as it seduces. The upper notes, very high in the chest, remain the main weakness even if they are powerful and accurate: often attacked too brutally, with a too volcanic brightness, they do not fit well with an otherwise well-phrased vocal line. The variety of colors and styles deployed by the tenor throughout the opera, which calls upon the whole palette of emotions and nuances of which the singer is capable, from jealous rage to magnanimous forgiveness, is on the other hand his great strength.” Le Blog Lyrique, 1 February 2010

Stiffelio, Met, January 2010: “On Monday night, José Cura proved himself to be an excellent heir to Domingo, dominating the action from his entry. The character of Stiffelio is a bit more complex than your average Verdi tenor. This is an older man who must deal with his wife's extramarital affair, but stay true to his religious beliefs. There are many psychological, internal moments with fine acting nuances. Cura handled these well, but sounded most comfortable in the second and third acts when he could let his big voice rip through Verdi's arias and ensembles.” Superconductor, 12 January 2010

Stiffelio, Met, January 2010: “As Stiffelio, the “Argentinian tenor Messiah” José Cura sounded forced at times, though warmly lyrical at other times.” Innovative Music Programs, 23 January 2010

Stiffelio, Met, January 2010: “It is more difficult to know what to make of José Cura. He is at this point a damaged singer - the voice, which was once both lovely in tone and powerful enough for the major spinto roles, now seems to lapse into a kind of guttural quality at any opportunity. The basic tone color is too often leathery, and anything above G at the top of the staff begins to sound unsupported, taking on an almost falsetto-like quality. More disturbingly, Cura often has difficulty tuning the voice in the middle of his range, where most of any tenor‘s singing lies, and too often he seems to slide from note to note without ever quite landing square in the center of any note. If he is nonetheless a serious interpreter, Cura rarely seems to bring more than a series of poses to his performances, and if there is one Verdi role which requires a singer who can act, not only with the voice, but in all the interstices where he does not sing, Stiffelio is that role. Cura’s stage deportment is one of considerable dignity - one suspects that vocal caution may play as much a part here as a natural reticence - but he was unable to convey with the pathos of the end of the Act II, when he has become aware of the deception, or the natural dignity of the final scene.” Opera Britannia, 26 January 2010, Richard Garmise

Stiffelio, Met, January 2010: “José Cura (Stiffelio) offered a bravura tenor version suitable for the character in moments of anger, which sometimes resulted in a certain lack of refinement and prevents him from achieving enough lyricism in those moments when the shepherd must keep his moderation. His total dedication and fierceness [of delivery] provided for an undisputed ovation at the end. I must note that, having been in this theater with Barenboim, Kleiber, Mazel, Levine and many others I have never heard an ovation like that which was levied on Sunday.” HoyesArt, 15 February 2010

Stiffelio, Met, January 2010: “The title role is sung by José Cura, who reins in his burnished, sometimes wild tenor voice to give an intelligent and effective performance.” New York Times, 14 January 2010

Stiffelio, Met, January 2010: “The performance caught fire in the duet, which becomes a trio with Stankar, in which Stiffelio (José Cura) discovers that Lina is missing her wedding ring and explodes with fury. The first act’s climatic largo septet and chorus and the ensemble’s stretta, both forcefully kicked off by Cura, were as grand as they should be. Cura’s brooding Stiffelio, bent on divorce, and Radvanosky’s contrite Lina capped their portrayals with a penultimate scene ‘Opposto e il calle’ of full intensity, and emotional subsequent scene in the church, suggesting the peace they have made with each other.” Q on Stage, January 2010

Stiffelio, Met, January 2010: “José Cura is a tenor with a baritonal approach. This suits Stiffelio better than most Verdi tenor roles — the part sits low, the high lines come only at emotional climaxes, and Cura does emotional climaxes well. His meditative moments are pleasing, his more passionate ones edge into growling lack of clarity.” Opera Today, 18 January 2010

Stiffelio, Met, January 2010: “The Argentinean tenor José Cura found himself in the peculiar position of having to sing a rarely performed role conducted by the man most closely identified with it. His voice is on the dark side, almost covered at times, but his dramatic portrayal of the anguished, betrayed minister supplied the intensity sometimes lacking in his vocal delivery.” Classical Source, January 2010

Stiffelio, Met, January 2010: “The Saturday matinee I attended was sold out and the cheers from the packed house would have probably continued until the evening performance—had the houselights not come up. Tenor José Cura as the deeply conflicted title character headed a first-rate cast—all of whom sounded glorious and all of whom acted persuasively.” Proactive Leadership Mag, 10 February 2010

Stiffelio, New York City: “José Cura was cast in the title role, one of Verdi's most layered. He sang it with great variety, from amiability in the barcarolle to jealous rage to chastened transfiguration. Some of del Monaco's careless work remains, along with his production credit. There's still a lot of intimate conversation performed from opposite ends of a twenty-foot dining table. It's too much to ask of singers that they execute unrealistic acts in realistic, detailed scenery. But Cura nonetheless gave a thoughtful, rounded characterization. His voice sometimes sounded worn - in the great Act II quartet ‘Un accento proferite’ it sounded inappropriately deflated - but he never sang beyond his means. He is also one of the very few singers who know just how softly it is possible to sing at the Met, and his ‘Opposto è il calle’ was real bel canto.” Opera News, April 2010

Stiffelio, New York City: “Verdi’s “Stiffelio” at the Met Opera is a mesmerizing affair. José Cura digs into Stiffelio’s sorrow with restraint.” The Stamford Times, 15 January 2010

|

|

Extraordinary drawings by the incredibly talented Denise Gagné Ash

|

||||||

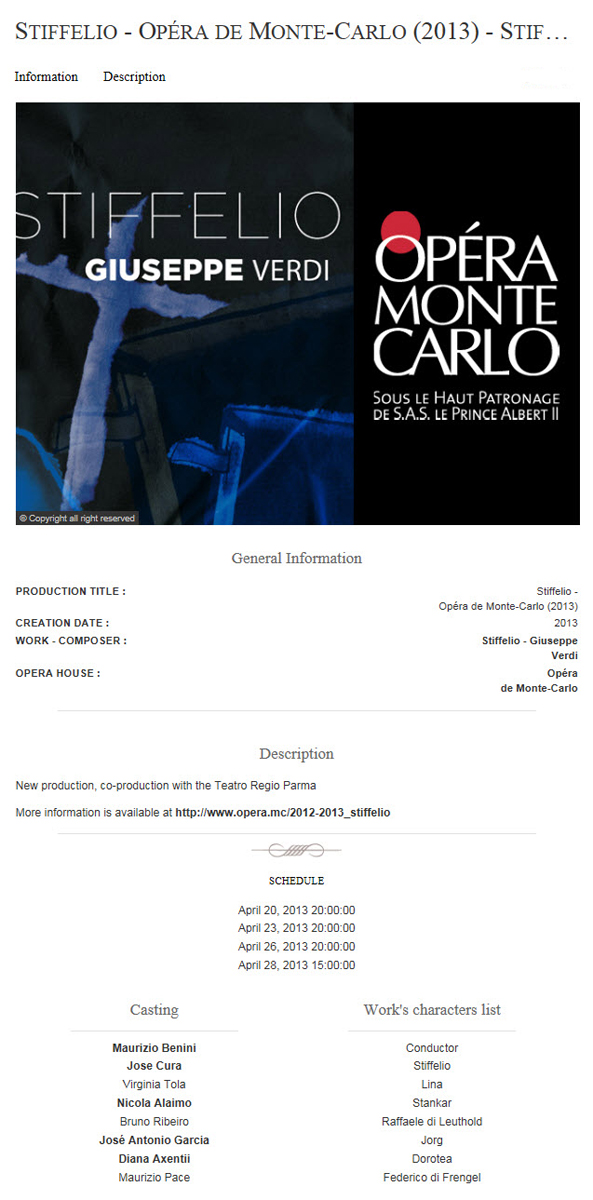

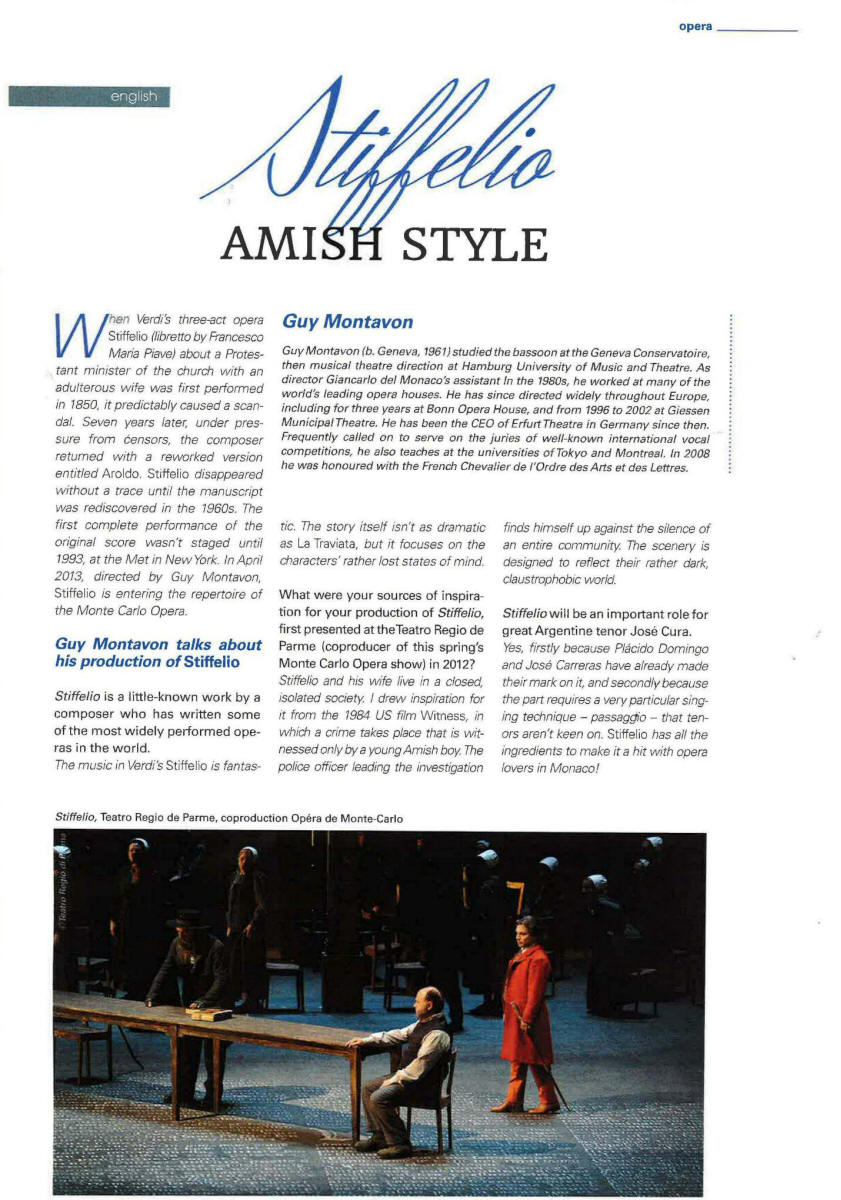

Stiffelio

Monte Carlo

|

Stiffelio, Monte Carlo: “In a role he thoroughly knows - he made his debut at Covent Garden in 1995 - José Cura is once again unreservedly involved. The incarnation is striking, overwhelming. We will pass over with a certain indulgence the timbre whose coppery colors is beginning to tarnish, the high notes that tend to open too much, but it is surprising that a singer who is also a conductor allows his phrasings to languish at this point to the detriment of the measure and the rhythm. Charism does not do everything.” Diapason, 26 April 2013 |

|

Stiffelio, Monte Carlo: “The famous Argentine tenor José Cura (also an actor, composer and conductor) plays Stiffelio with a dark staining of his masterful-- though slightly worn--voice, suggestive phrasing and rare stage personality, giving moral power of this pastor of the Protestant sect. Cura also shows the transformation of Stiffelio: at the beginning of the first act, when he receives the papers compromising his wife, he is ready to forgive but by the end of the same act is suffering the negative emotions of the wounded man. True forgiveness will only be possible in the third act, when Stiffelio discovers his true mission …” Maestro, 10 May 2013 |

|

Stiffelio, Monte Carlo: “In the title role, José Cura shows himself to be dramatically convincing (as expected), although it is sometimes difficult to distinguish his Protestant pastor from Otello, which, along with Samson, appear to be his ‘favorite’ role. Vocally, Cura always displays an incredible vocal health, in a central range that nevertheless never fails in the high notes, allowing him to take care of his singing line, a rare happiness for the ears.” ConcertoNet, 20 April 2013 |

|

Stiffelio, Monte Carlo: “The Argentine tenor José Cura made his Covent Garden debut in the role of Stiffelio and now that he is older, the role fits him like a glove. Stiffelio is not a ‘jeune premier’ who, like so many Verdi heroes, is head-over-heels in love with the soprano and making great love declarations. Rather, he is an older, married man who—carefully expressed—finds disappointment. Cura has a dark, baritonal voice that perfectly fits with the dark story he tells in the first act, in which he speaks of the great sinfulness he has seen during his travels. He still does not know that sinfulness has already crept into his own home…Viva Verdi!” Opera Magazine, 29 April 2013 |

|

Stiffelio, Monte Carlo: “In the title role, José Cura offers a profusion of very moving operatic accents and rare intensity. The vocal structure and tonal richness of the Argentine tenor assures a stage charisma where the exigency of the spiritual vies with the ardor of passion--and this he offers from his first appearance on stage to his ascent to the pulpit at the end. He collapses at the end of Act II in a mystical prayer with an emotional paroxysm that literally seized the audience…” Musicologie, 25 April 2013 |

|

Stiffelio, Monte Carlo: “It is not enough to have great voices to save Stiffelio. What is needed is the addition of soul in the heart and throat, a frankness, an urgency, a dramatic momentum (the famous Verdi slancio), otherwise it falls back into the routine of note for note, making the staging do the rest. Invested like no other, carrying on his shoulders, from his entrance, of the sins of the world and that of his wife’s to come, José Cura, transcendent, brings to the title role a valor, a generosity, a brightness of timbre, a bite, a cast-iron professionalism.” Sortir, 21 April 2013 |

|

|

.jpg)

%20ed.jpg)

.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)