|

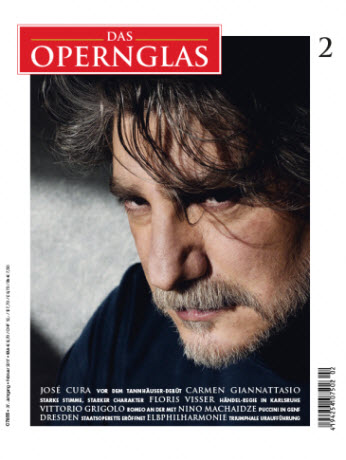

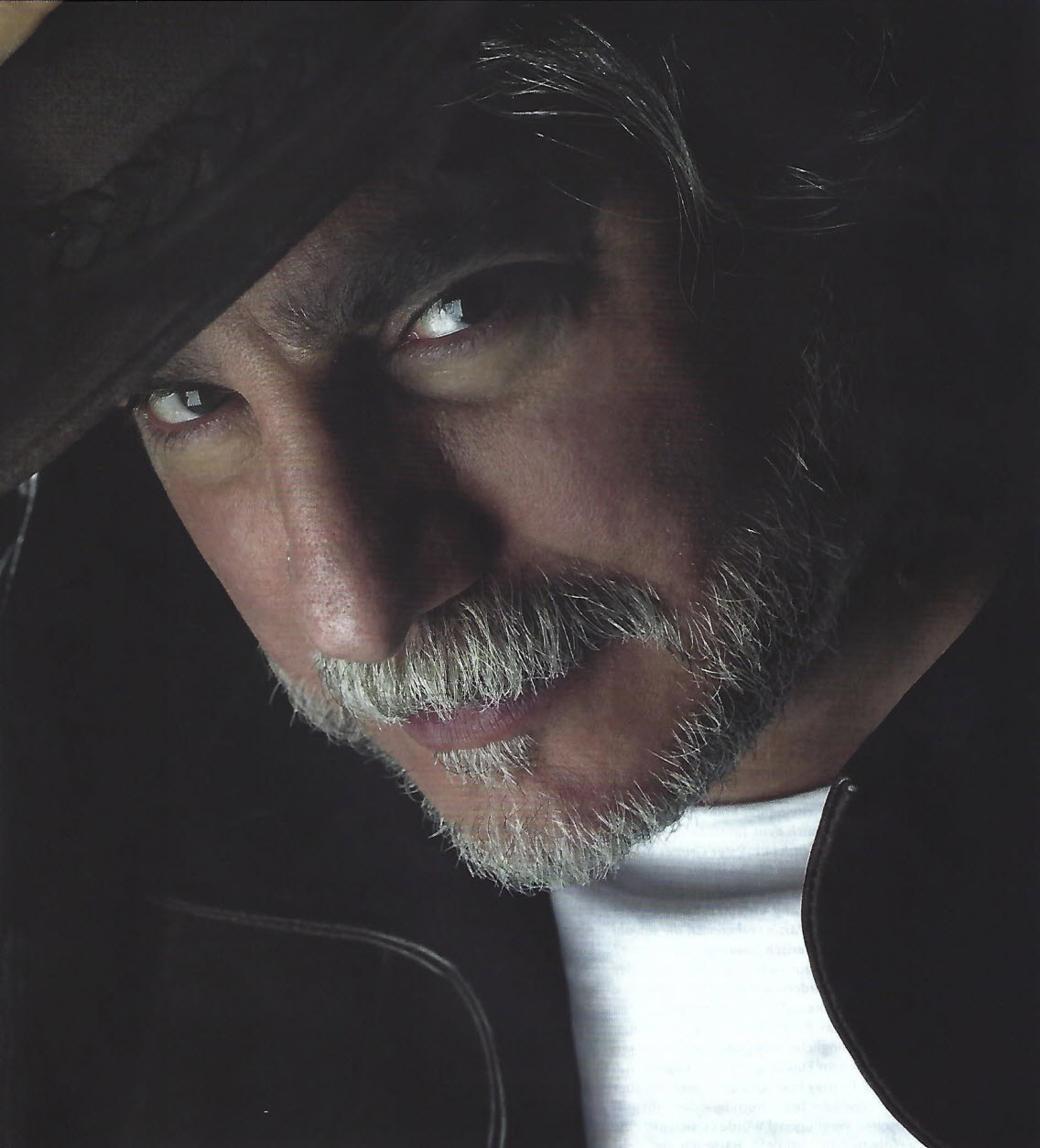

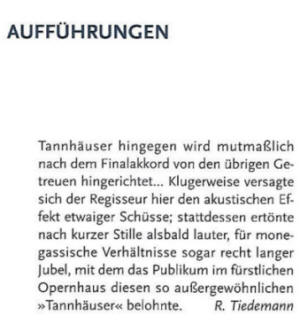

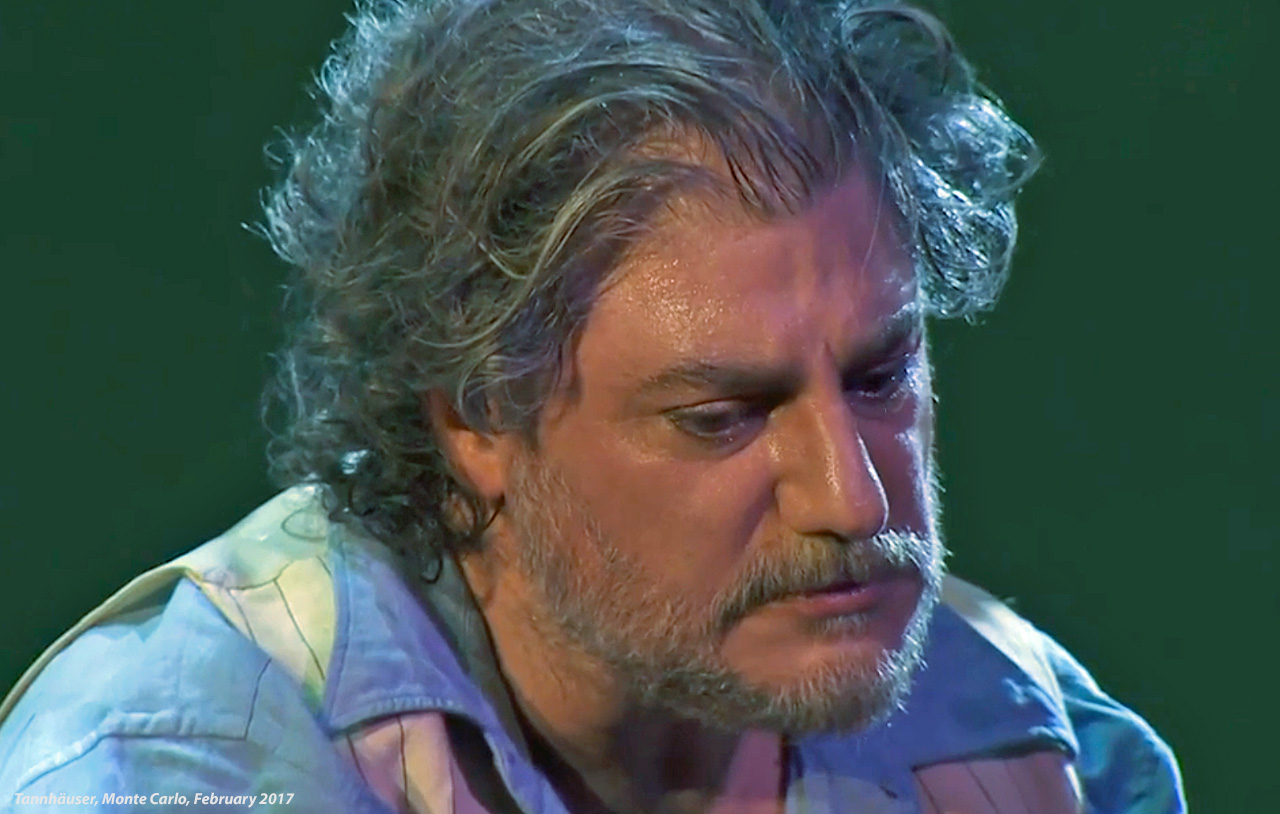

The Cura Standard

Das Opernglas

Rakf Tuedenab

February 2017

[Excerpt // Computer-assisted translation]

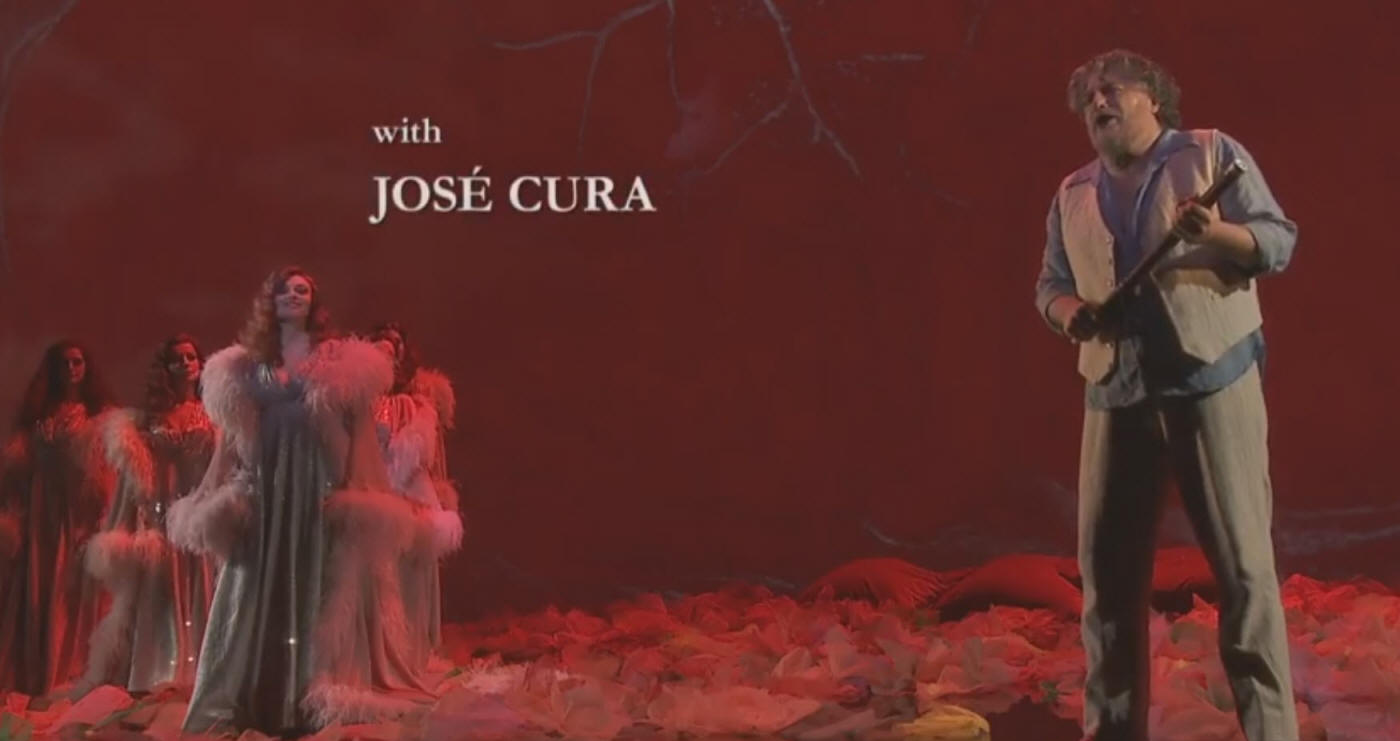

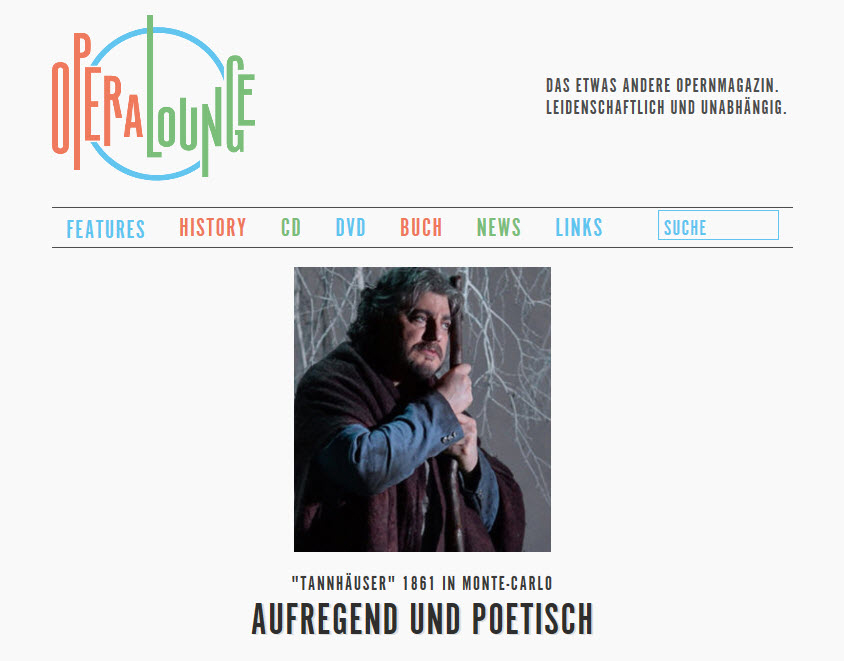

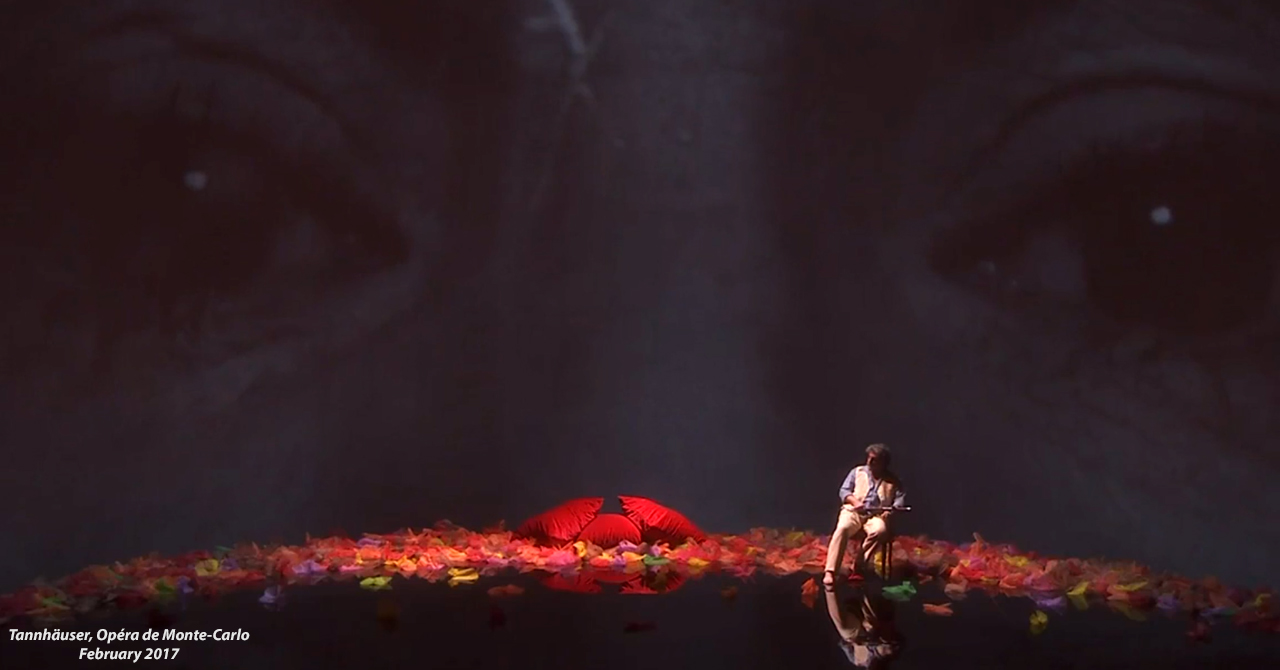

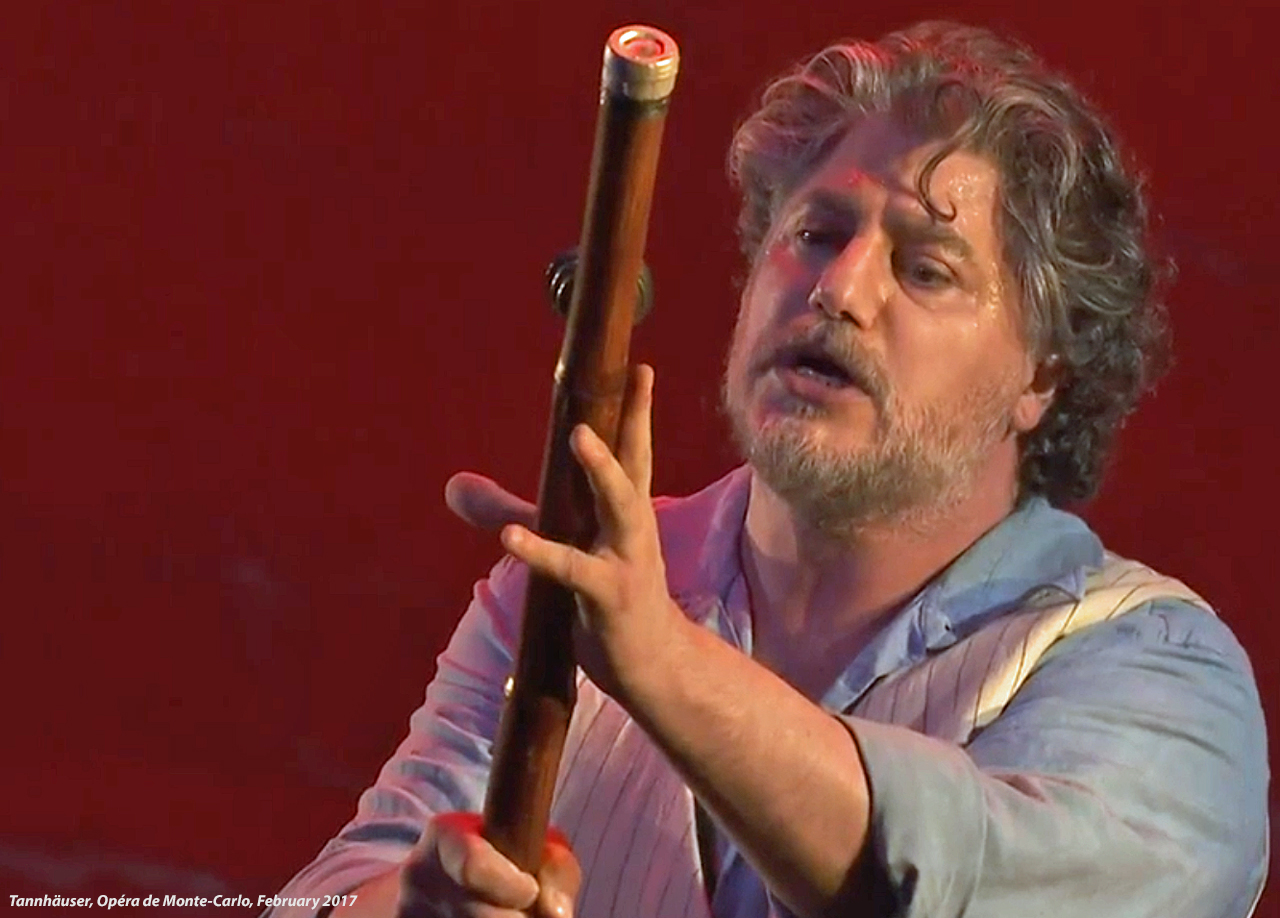

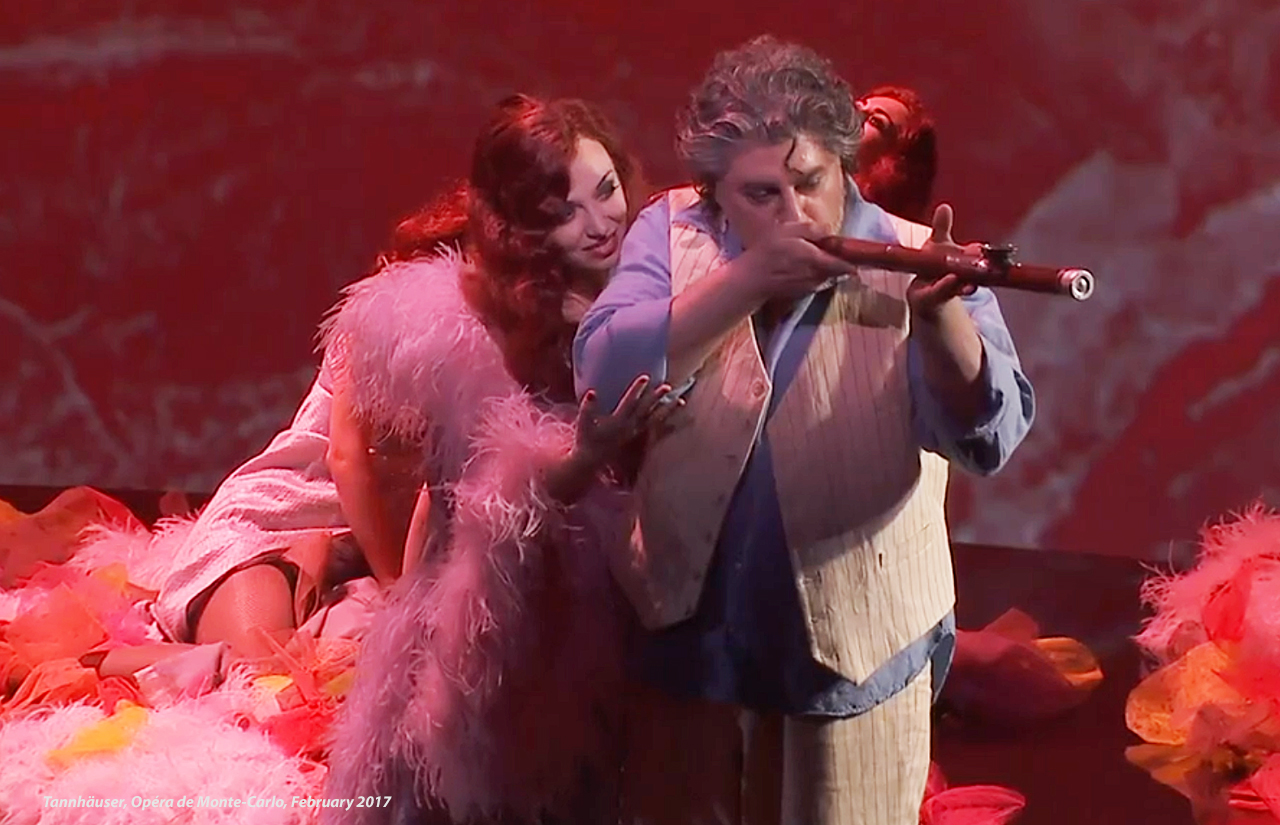

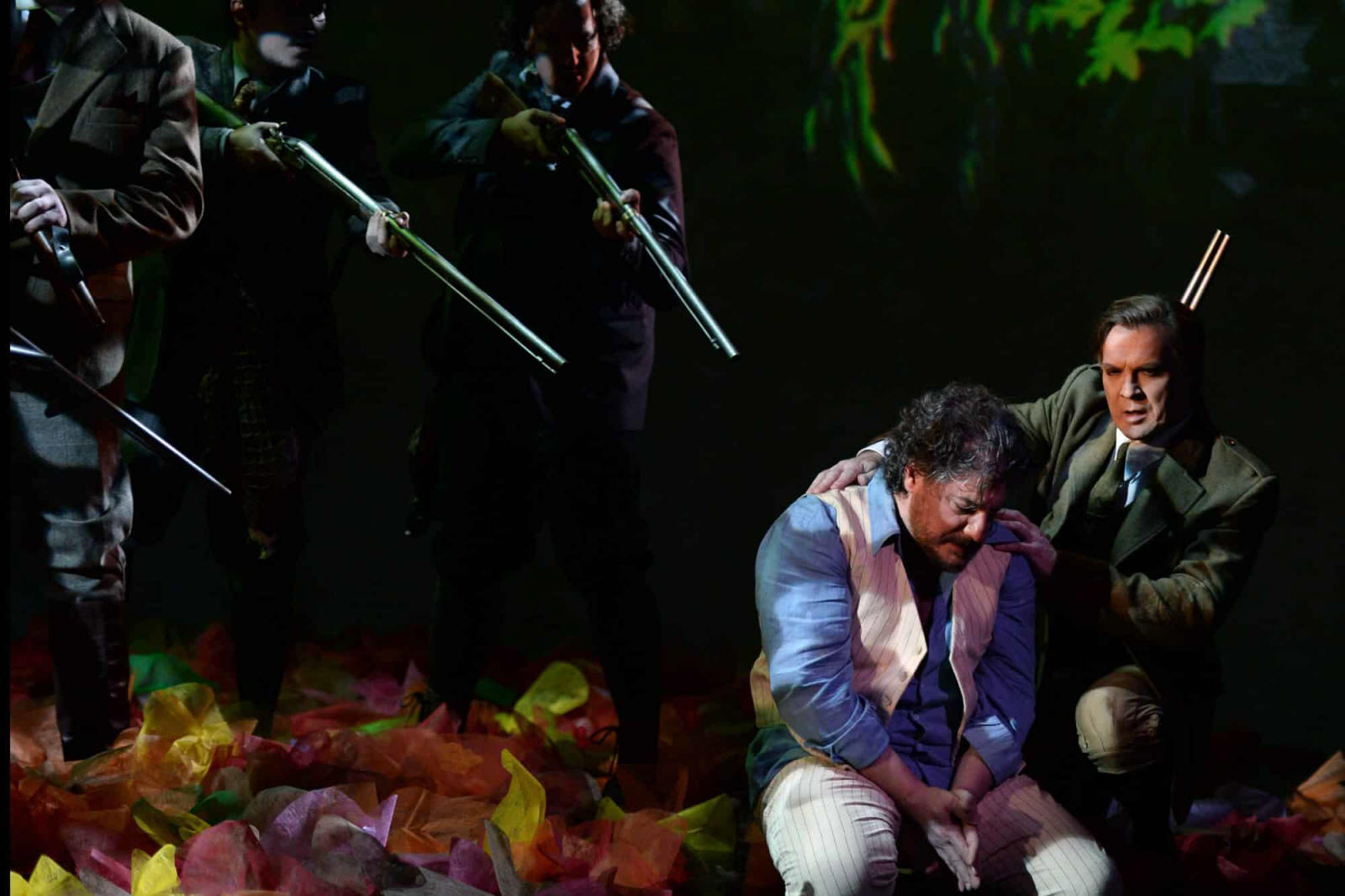

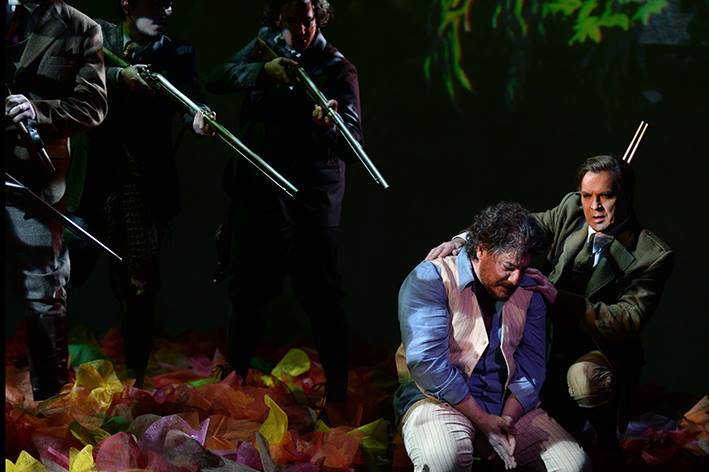

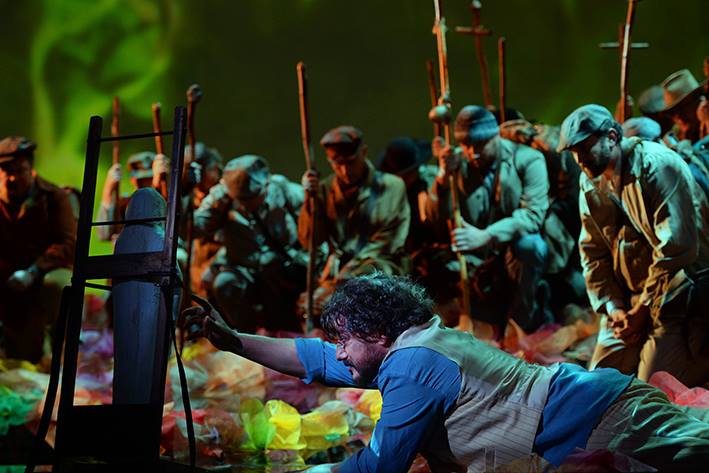

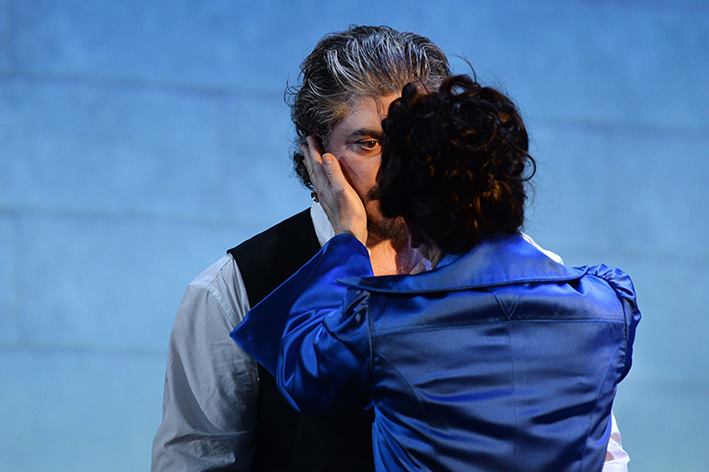

Q: This season offers two eagerly

anticipated role debuts: Tannhäuser and Peter

Grimes. Starting with the Wagner opera, which comes

out in February at Opéra de Monte-Carlo: As they are doing

the French version, the language actually should not be

the problem; so what is the main challenge for you?

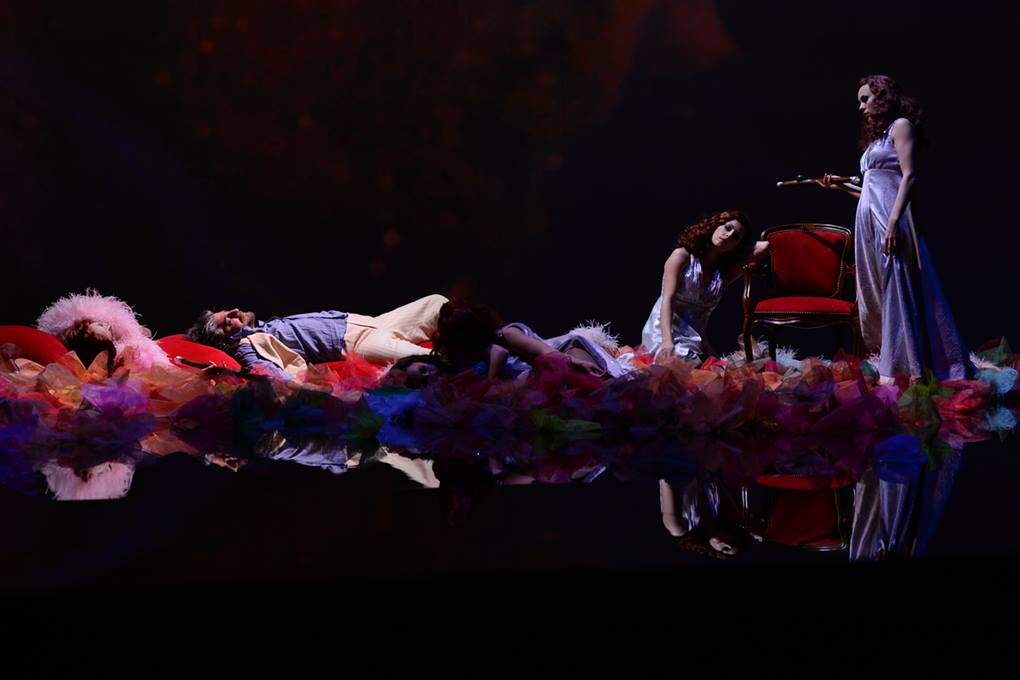

JC: As a performer who prefers

a natural body language (no wonder my favorite pieces are

late Verdi, Puccini and the Verismo), to convey Wagner’s

amazing musical rhetoric with a believable use of histrionics

will certainly be my biggest challenge. Also, the sometimes

forced tessitura in which the tenor sings is a problem to

face, but I trust I will be able to solve it by adapting

my singing to the needs of the score.

Q: Did the fact that they are giving

the opera in French allow you consider this role?

JC: You are my witness in this: during

these long years since we know each other, my only reason

not to sing Wagner has always been the respect I have for

the audience, a respect that doesn’t allow me to sing in

a language I don’t currently speak. Whether people like

it or not, there is a Cura “standard” in what refers to

interpretation of roles, and that standard is strongly bonded

to the connection between the text and my body language—something

that is conditio sine qua non for prose actors, but

seems not to be so in opera. Or at least not always… There

is no way of having an honest body language if the words

don’t belong to your cultural baggage. That is why, when

I was asked to do Tannhäuser in French, a language I speak

fluently, I immediately accepted, sure that this is probably

my only chance of singing Wagner.

Q: And, honestly, would the

German version really let you sweat?

JC: I may solve it with phonetics,

I have a very good ear after all. But it wouldn’t be what

people expect from me. One thing is people saying that Cura

is not as good as some other xx artist (for this is a point

of view), but one other very different thing is saying that

Cura is not as good as Cura himself…

Q: You once also planned

Parsifal, but for some reasons this has not been realized.

I assume that in the meantime this dream of a role might

finally be left unfulfilled?

JC: This was a concert version

that was cancelled. A pity indeed!

Q: Coming back to Tannhäuser:

For Paris, Wagner himself worked together with Charles Nuitter

on the French translation of the libretto. Much more important

were the changes to the score itself, which not only took

the conventions of the Paris opera houses of that time into

account, but also shows quite clearly the composer’s development

during the years, as in the meantime he had already finished

his work on Tristan. Which version of the score precisely

do you follow in this new production at M-C Opéra and what

are the merits of the different editions of Tannhäuser?

JC: I haven’t got enough authority

in Wagner to answer your question. I am discovering a whole

new world now, and in such discovery I am proceeding with

the innocence of a child and the extreme precaution of a

wise adult…

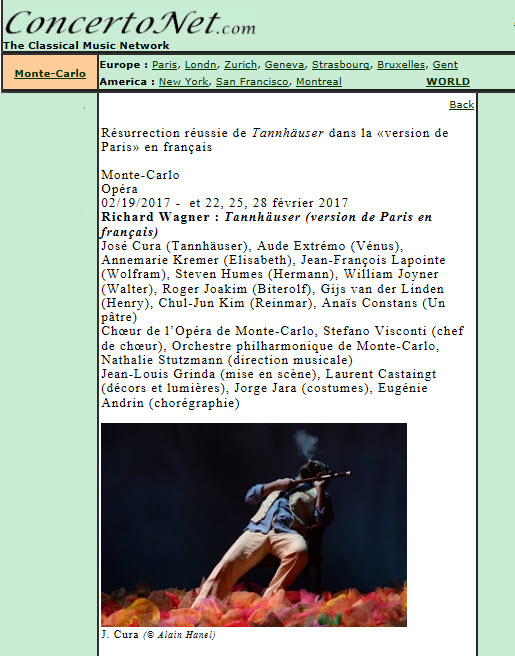

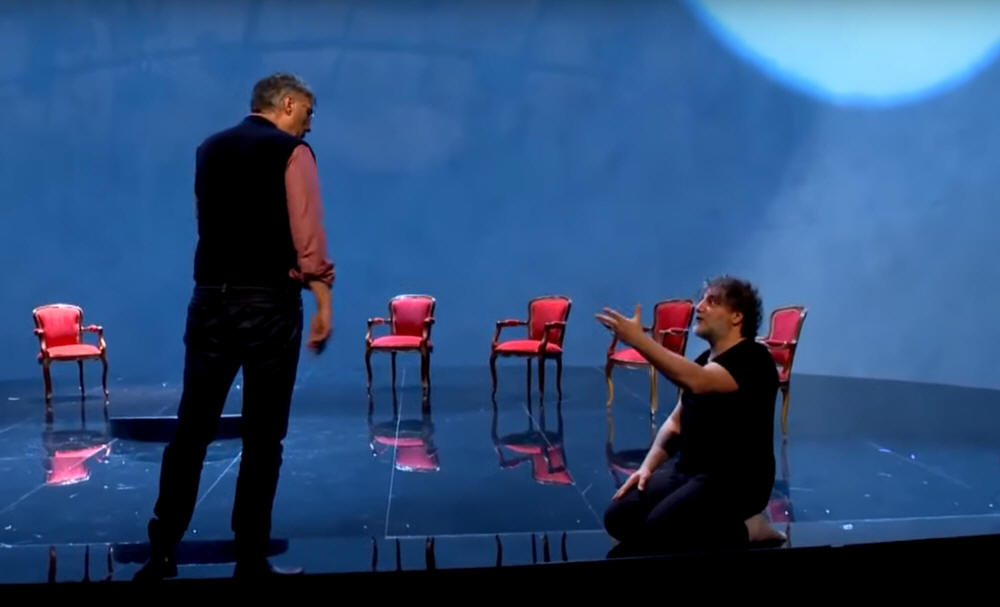

Q: In Monte-Carlo the opera

will be conducted by Nathalie Stutzmann – a singer-conductor,

as you yourself. Have you already experienced her working

in the pit and how does the communication about the musical

interpretation goes on?

JC: I am not a singer-conductor,

but a composer-conductor who later on became a singer. But

I understand your question in the sense that we all, me

the first, expect Mrs Stutzmann to be sympathetic as only

a singer can be when conducting equals. It is certainly

a huge opera full of very difficult singing, so a conductor

that can “hold” the orchestra with authority while accompanying

the singers with love and understanding is determining.

Q: Do you expect that your approach

of the role will differ from what we usually hear?

JC: As said, my authority in Wagner

is very incipient, so I cannot tell if I will be able to

do a “creation” out of Tannhäuser, or just a good professional

work. Let’s talk again in March…

Q: Just three months after

Tannhäuser, the next big role debut will be coming

up: Peter Grimes. This time, at the Oper Bonn, you

are also doing the staging as well as the setting. Isn’t

this quite a challenge for an artist preparing a new role?

JC: It is a huge challenge

and a big risk: the challenge has to do with the amount

of work on my shoulders and the risk with spoiling myself

with the fact of creating my interpretation in the best

of ways: in total agreement with the director… Jokes apart,

it is a hell of a work, but also a super rewarding one:

The epitome of artistic enjoyment! If it would have been

a more frequent opera, probably I wouldn’t have directed

and sung it, but when will I have again the possibility

of staging such an amazing piece that is not so often performed?

I couldn’t lose this one chance!

Q: As I remember Peter Grimes

is one of your “dream roles”. What attracted your interest

in this role – and what are the challenges – vocally? dramatically?

JC: Coming back to what I said

about my difficulties to deal with Wagner’s musical rhetoric

and dense libretti, Peter Grimes is exactly the opposite:

the perfect symbiosis between music, text and action. A

dream for the kind of performer I am. Every moment is a

challenge in this piece, but such a tasty challenge that

each step taken with risk is also a step taken with pleasure.

Q: What differences, resp.

what similarities between your two new roles, Tannhäuser

& Peter Grimes, do you see – vocally? dramatically?

JC: Both are marginalized guys,

but for different reasons: While Tannhäuser challenges his

fate, Peter Grimes suffers its consequences. Vocally, Tannhäuser

relies more on great music, while Grimes relies on the use

of the voice to convey a state of spirit sometimes just

by the voice alone, like in the big monologue of the third

act.

Q: What are the crucial points

in regards to the staging? How far did you come up to now

with the conception of your staging – and can you already

give us some insights?

JC: The show will be based

on the multi-uses of an emblematic Aldebourgh’s building…

Q: This season also offers

three of your most important roles: Calaf, Dick Johnson

in Fanciulla and Otello. Would you consider these

roles as your current signature roles?

JC: I surely can say that Otello

and Dick Johnson are signature roles of mine, as well as

Canio, Samson and, hopefully in a couple years, also Grimes.

About Calaf, although I have portrayed him several times

with success, I don’t consider it a signature role because

he does not offer enough “flesh” to carve. It is a night

of great singing, not a night of deep psychological inside.

Q: Any more new roles to come?

JC: Developing Tannhäuser and

mainly making Grimes mine will take some years, so no other

roles as of today. On the symphonic side, yes, next March

is the world premiere in Prague of my oratorio Ecce Homo,

written in 1989!

Q: It’s about 25 years ago

now that you relocate you and your family’s lives to Europe,

where your international career started soon. We followed

your steps and sometimes unusual ways all over the years

and for me personally it is always a great pleasure to talk

to you – this time even with a bit more delight, because

it relates somehow to my own jubilee: Your first interview

has been one of the big cover stories of “Das Opernglas”

in 1997 – in my very first year as editor-in-chief of this

magazine. Looking back to all these years, you too will

sum up that the business has changed a lot, right?

JC: The world has changed a

lot, and our business has changed with it. The new technologies

in general, and internet in particular, have inoculated

in the mind of many that long-time effort and studies are

not necessary anymore to succeed. Nowadays, everybody is

a photographer, composer, writer, movie director, singer,

actor, cook… Never more than today has the difference between

being “famous” and being “great” been so accentuated. Once

upon a time you needed to be good to be famous. With time,

you also may become great and be venerate for your wisdom.

Today you can be easily famous, without having anything

to impart to society apart from your own home-made garbage,

canalized through “the world wide net”. So far so good:

everybody has the right for their minute of fame… But in

the long run this is seriously affecting the quality with

which we do things as the great majority of people prefers

to “enjoy” bad stuff with which they identify rather than

great stuff that make them feel inferior if they are not

well in their heads. Other’s greatness has always had two

different effects in people: envy and hate —because I cannot

be like you—, or admiration and gratitude —because others

greatness stimulates me to improve, to grow, to become a

better individual. This ancient phenomenon, old as our species,

is today multiplied ad infinitum by the accommodating easiness

of internet.

Q:

One last question, coming back once more to Tannhäuser:

This is not only an opera about a singers contest and the

contrast of the different types of love. It also deals with

the status of the artist in society and with the meaning

of art itself. What would be your answer today to the different

questions in this opera?

JC: I think the answer to this question is embedded

in my long answer to the question before.

|

%20a.jpg)

%20a.jpg)

%20a.jpg)

%20a.jpg)

.jpg)