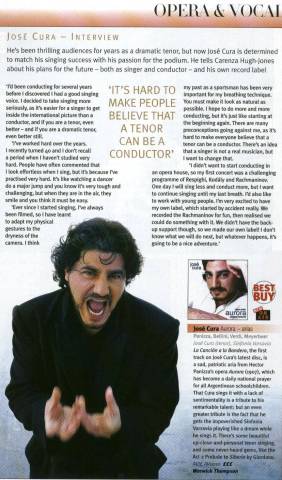

Make Room on Olympus Sacred Monsters

(excerpts)

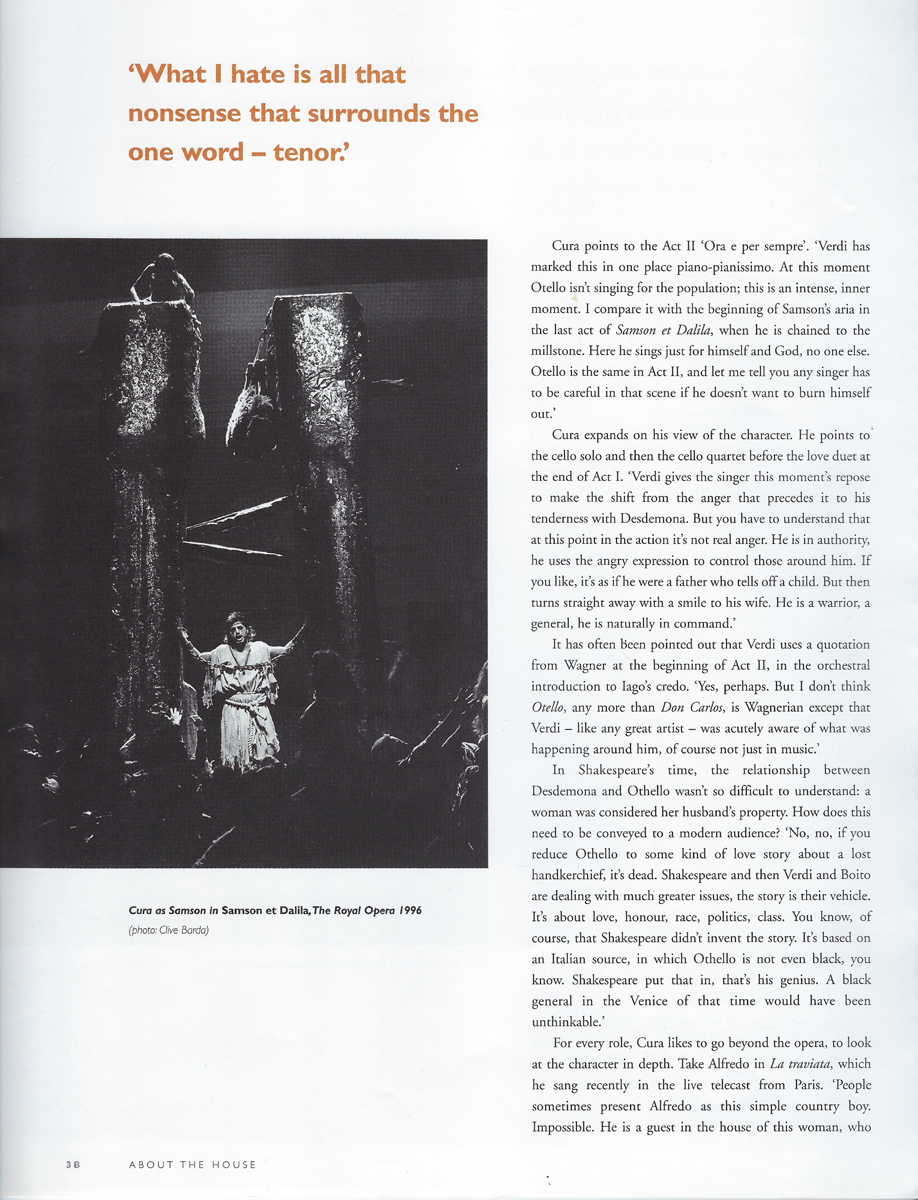

M Gurewitsch

NY Times / 28 May 2000

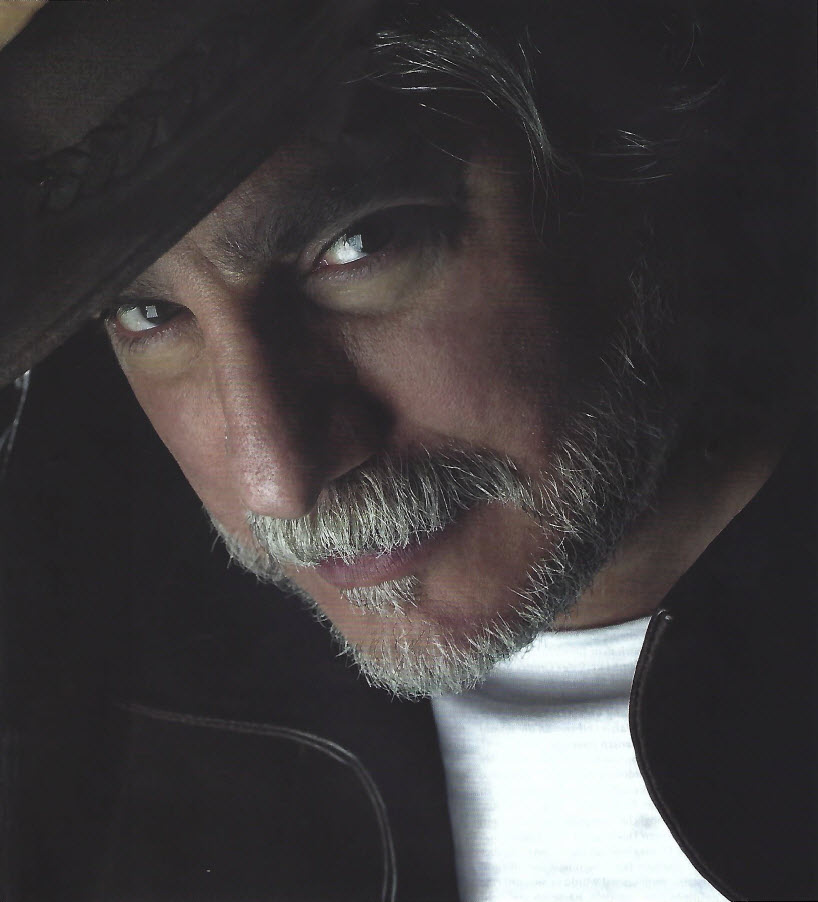

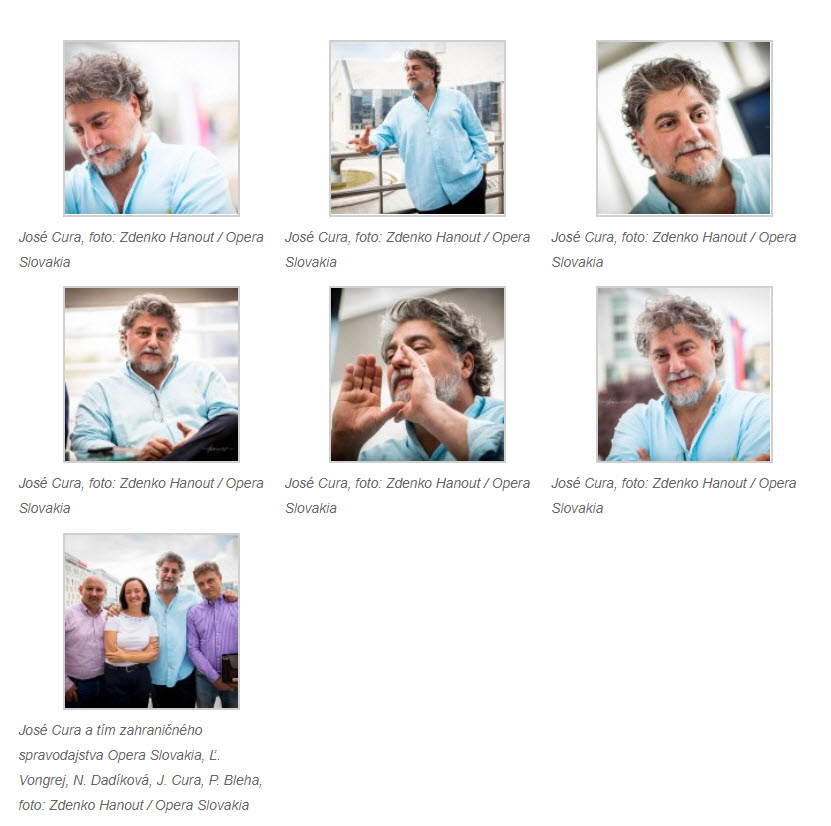

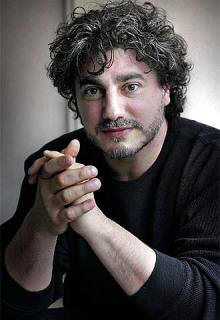

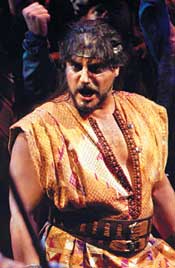

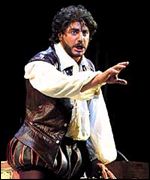

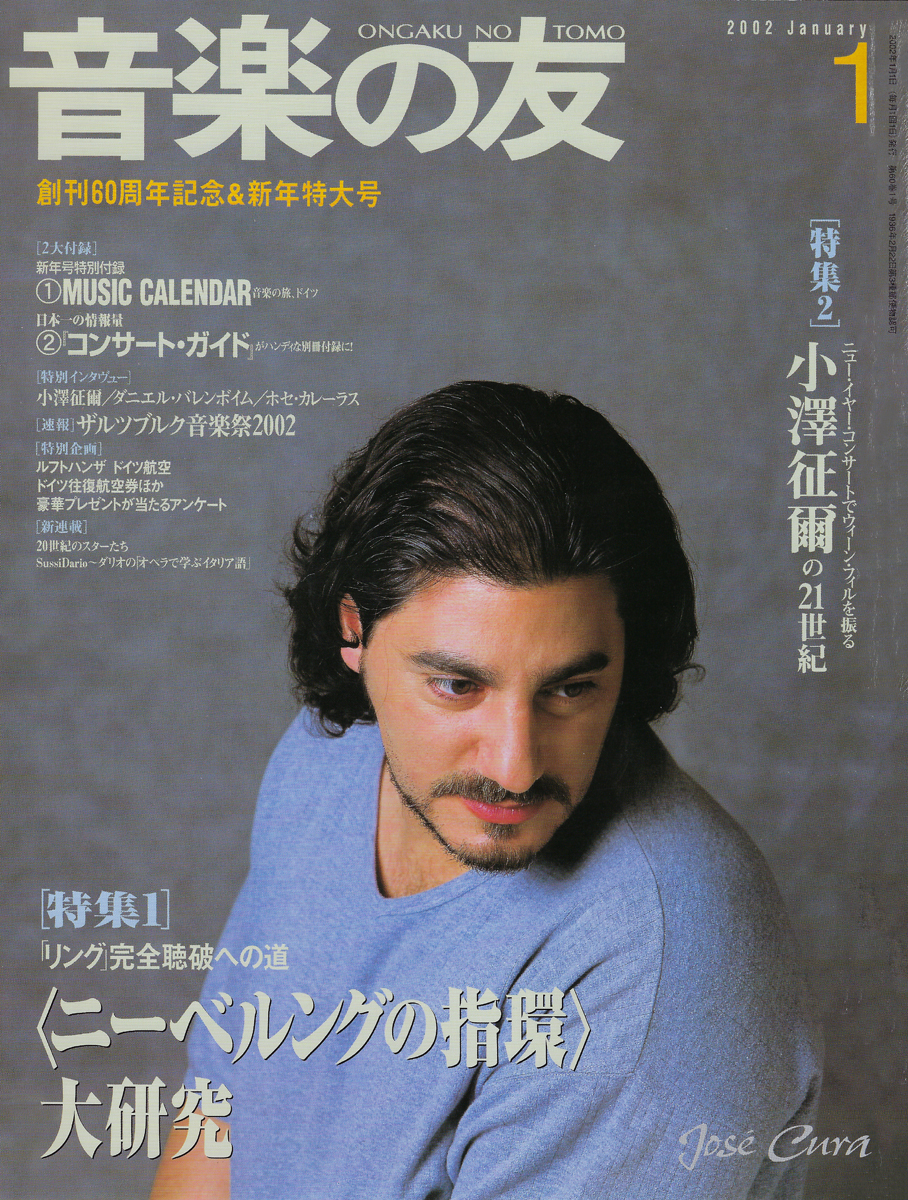

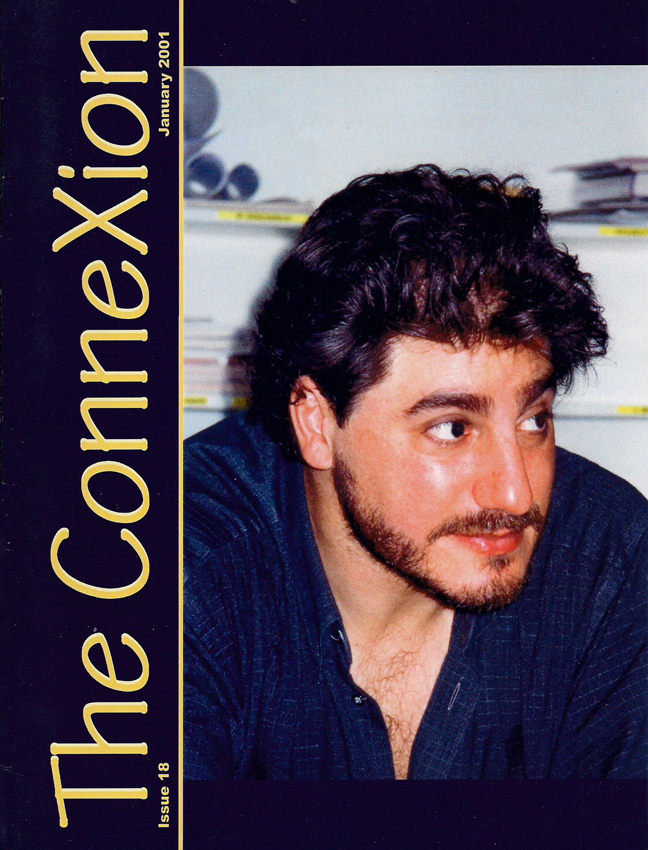

The epitome of the sacred monster at the moment is

surely the Argentine tenor José Cura, 38. So far, New

Yorkers have seen him just three times, in a single

production, as the Sicilian lothario Turiddu in

Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana, amid the

wreckage of the once picturesque staging by Franco

Zeffirelli, woefully led by Carlo Rizzi and partnered by

the uncongenial Santuzza of Dolora Zajick. Thanks to

Placido Domingo in his capacity as artistic director of

the Washington Opera, audiences in the capital have

taken Mr. Cura’s measure in two of his signature roles:

Saint-Saens’s Samson and Verdi’s Otello.

In the biblical spectacular, he

bore the destiny of the despondent Chosen People on

heroic shoulders, his prophetic song ringing forth with

dark, blazing grandeur. His authority was total. But

his last Washington Otello this spring was an

altogether more daring affair. Of the British stage

idol Edmund Kean, Samuel Coleridge wrote, “To see him

act is like reading Shakespeare by flashes of

lightning,” and so it was with Mr. Cura in Verdi’s

Shakespearean mode.

While still singing in choirs in the

mid-eighties, he devoted himself to composing and

conducting. In 1988, he met maestro Horacio Amauri

who gave him the definitive basis of his singing

technique. José Cura left his native country for Europe

in 1991. He lived in Verona Italy for three years and

then in January 1995, he moved to Paris where he now

resides together with his wife and three children.

Praise or censure? That depends

on your point of view. Between lightning flashes fell

long spells of pitch dark. On prior occasions in

Europe, Mr. Cura had executed the notes with a

scrupulousness that had only boosted his tremendous

conception of the part. This time, rather than sing the

music, he chose to channel the character. Call it

extreme music drama, and sway, if you can, whether it

unfolded through or in spite of the music. Over the

radio or on a recording, it might have sounded

grotesque, but it was hair-raising to be there.

Among those who witnessed Mr.

Cura’s Washington Otello is Barbara cook, the Broadway

star of mid-century who created the roles of Marian the

Librarian in “The Music Man” and Cunegonde in “Candide,”

and continues to wrap audiences around her finger in

cabaret and concert performances. (One prominent London

critic has repeatedly placed her artistry on a par with

that of Callas.)

Unlike critics, whose professional

obligation to endure upward of a hundred evenings of

opera a year many has patently come to regret, Ms. Cook

has the luxury of attending purely as the spirit moves

her. For the last year or so, between engagements of

her own, she has traveled as far a field as Madrid,

Paris and London to keep up with Mr. Cura’s

performances.

Why such devotion? “It’s the

total package,” Ms. Cook said recently. “In any era,

only a very few people are at the pinnacle. I can’t

think of anybody who sings as well, who acts as well,

who moves as well. It’s like watching a great baseball

player who has this terrific masculine grace. Whatever

things might be wrong with José’s performances, he has a

concentration that pulls you right into his world.”

This weekend, viewers in more than

a hundred countries will be tuning in for their Cura fix

in a live telecast of “La Traviata,” spread our over

installments on Saturday and Sunday, and shot in what

are billed as authentic Paris locations. (Cinema verite

meets Masterpiece Theater.) The prima donna is the

hitherto unknown Eteri Gvazava, of Siberia, cast, Mr.

Cura says, after the sort of talent search that produced

Hollywood’s Scarlett O’Hara.

By rights, Verdi’s tragedy of the

fallen woman redeemed by suffering is the soprano’s

opera, but this time it may be the tenor’s. Not that

Alfredo Germont, the romantic but callow bourgeois

papa’s boy who woos Violetta from her life of soulless

pleasure, is the sort of character one associates with

Mr. Cura’s brooding macho presence.

Mr. Cura has admitted as much,

adding: “Alfredo has gotten the greatest courtesan in

Paris to give up everything for him. There must be a

reason.” Americans may decide for themselves in the

fall, when the show is expected to appear on PBS; a

Teldec CD of the soundtrack, conducted by Zubin Mehta,

goes on sale here in July.

To a degree seldom if ever matched

in the annals of opera, Mr. Cura – also a composer and

conductor – marches to his own drum. On “Verismo,” his

latest CD for Erato, he dedicates a whole program to a

style of the late 19th and early 20th

centuries commonly thought vulgar and sensationalistic.

Acting as his own conductor, he sets out to redefine it

as a school of chaste refinement.

In the hit-and-run showstopper,

‘Amor ti vieta,” from Giordano’s dismal “Fedora,” the

delicacy of the phrasing (lines taken in a single breath

alternating with lines of similar length taken in two)

is as unusual as it is natural and discreet. There are

discoveries like this to be made throughout. And

nowhere will you find Mr. Cura clinging, in

self-indulgent spaghetti-tenor fashion, to top notes the

composer actually wrote or did not.

On his very best vocal behavior,

Mr. Cura here gives the lie to those who have said that

he has no technique. What we hear, by contrast, in such

daredevil performances as the Washington “Otello” is a

self-conscious, highly idiosyncratic technique fraught

with peril. How well it will Mr. Cura in the long run

remains to be seen. Self-immolation is not actually

required of sacred monsters, but longevity is not always

their strong suit.

Whatever lies ahead,

Mr. Cura has already earned his place as one of the most

supremely original performers of the age.

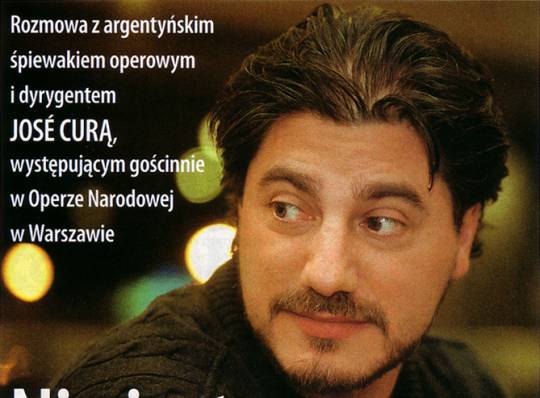

'I don't believe that

classical music exists'

Written by Jacek Hawryluk

Translated by Iwona Pomes

'Music can be played in your bathroom as well as in the

opera house.'

Jacek

Hawryluk: In the 90's some famous operatic singers

started to perform in open-air concerts at stadiums.

Mozart, Puccini and Verdi wrote music for opera houses.

Doesn't it contradict each other?

José Cura:

Don't forget that such composers as Mozart, Puccini,

Beethoven or Schubert were treated like today's pop

stars when they lived. Today they are considered to be

inviolable. They wrote music for opera houses for

technical reasons. They didn't know such things as

microphones, screens, etc. If they lived now, they would

write music suitable for open-air concerts.

J. H.: Do

you think they would be happy with these huge stadiums?

J. C.: It

is not a question of satisfaction. Music is everyone's

property. Many people are not able to go to an opera

house. It's just one of the ways of making people

familiar with classical music.

J. H.: Is

there any difference between a theatre and a stadium

when it comes to creating music and an atmosphere?

J. C.: The

atmosphere doesn't have to be different. A charismatic

artist can create it no matter where he or she performs.

J. H.: In

June you played a role in widely televised version of "

Traviata". This year we celebrate 400th

anniversary of opera. Do you think that broadcasting it

on TV will make it more attractive in the XXI century?

J. C.: This

is only one alternative. You can play music in your

bathroom at home as well as in a big opera house. You

can do it for 10 or 10,000 people. This year we

celebrate opera's 400th anniversary. About

50000 of them have been written over the ages, yet how

many operas do we know? Maybe 150 or 250.

J. H.: Do

you know why so many like listening to tenors?

J. C.: Yes,

I do. It's because the romantic roles are always played

by tenors. Baritones are associated with negative

characters; basses- with old persons.

J. H: What

does classical music mean to you?

J. C.: I

don't know why people distinguish popular and classical

music. For me there are only two sorts of music: the

good one and the bad one. Some classical tunes are

awful; some pop songs are wonderful and vice versa. John

Lennon's songs are no worse than those written by

Francis Schubert.

J. H.: Do

you think it's normal that Pavarotti and Domingo sing

together with pop stars?

J. C.:

Everything is all right if we are good. I hate

categorizing. My first photographic album will be

published soon. If you ask me whether it has anything in

common with music, I would say that it does. It's a

music of pictures.

J. H.: Why

do many singers like cooking?

J. C.: We

have creative souls. I hardly know any artist who

doesn't cook. I don't have my own formula. I like

improvisations.

J. H.: What

a pity. You will not give me a recipe.

J. C.: A

good cook can prepare something tasty from anything that

is in his refrigerator.

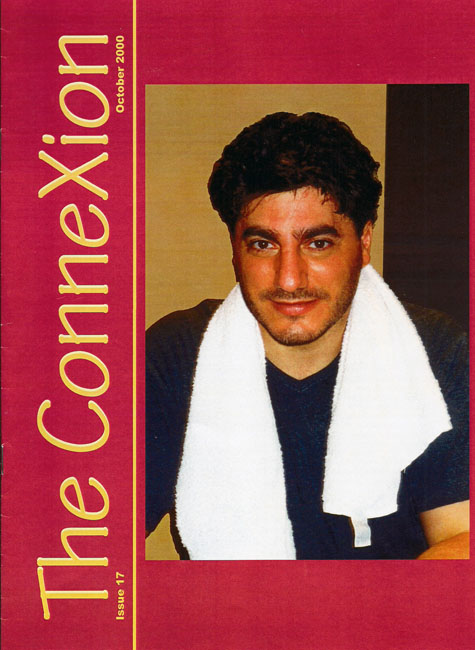

José Cura

was born in 1962 in Rosario, Argentina. He is a

professional singer, conductor, composer and

photographer. He is considered to be one of the best

young tenors in the world. José Cura and Ewa

Małas-Godlewska have recorded a CD called "Era Of Love".

They gave a concert in the National Opera on November 15th.

The original article was published in "Machina" monthly

magazine in November, 2000.

A Fright at the Opera

Ciara Dwyer

Sunday Independent

2000

A day trip to Italy?

It's well worth the trouble if José Cura is part of the

equation. Confirmed fan Ciara Dwyer had only one grouch

ITALY is a long way to go

for a day, but to see José Cura in an opera it's worth

the trek.

The Argentinian tenor was

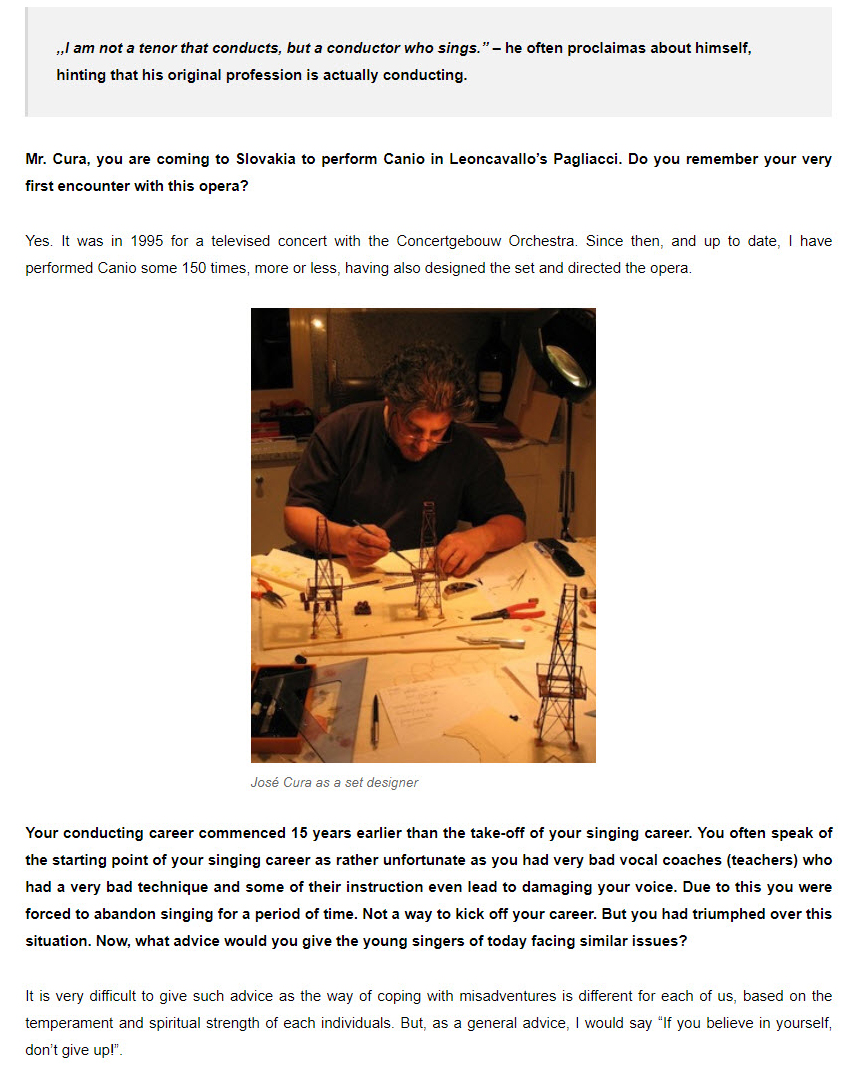

singing in Cavalleria Rusticana and Pagliacci.

The minute I heard about the concert I booked my ticket.

I couldn't afford it, but what the hell, didn't I have a

credit card?

I spent hours shouting down

the phone to the box office staff at Florence's Teatro

Communale. Nobody seemed to speak English. I had no

Italian. Still, my Trojan persistence paid off. A day

and a half later, I received a fax confirming that my

ticket was booked.

At first, I didn't tell a

soul that I was going. Too cute to draw the hassle of

real-world finances on myself, I knew that my mother

would taunt me with Preliminary Tax bill reminders. What

cared I for the real world when I was caught up in

over-the-top arias?

Ever since I interviewed

Cura last July, I am a changed woman. BarraO Tuama,

Cura's impresario, thought that I was smitten by José.

And indeed I was. But that was just the tip of the

iceberg. I became opera-mad.

Back in Dublin I bought

every book that exists on opera: Bluff Your Way in

Opera; Opera A Beginner's Guide, complete with cartoons

of Pavarotti. No tome was too heavy or too expensive.

One Sunday afternoon, the sort of day when most couples

are romantically sauntering down Dawson Street, I left

Hodges Figgis on a high. I had just picked up the last

available copy of an encyclopaedia of opera. I looked at

the colour photos, found one of Cura in Cavalleria, and

that was that. I had to go.

But my opera obsession goes

way beyond Cura. Every week I visit the classical

section of HMV and buy CDs complete with the librettos.

I now spend most Saturday nights sitting up on my bed,

headphones on, rocking to the music and reading the

librettos in Italian. It is a tricky process but well

worth it when you hear some of the lines. In Cavalleria,

Turiddu serenades his lover Lola: "If I were to go to

paradise and you were not there, I wouldn't stay." I sit

in my flannel pyjamas longing for the day that a man

will say such things to me.

NOW my life is measured out

in Cura concerts: Il Trovatore in Madrid; Otello in

Covent Garden; Aida in Athens. I plan to go to the lot.

I even joined his fan-club. So of course I was ready to

fly to Florence.

It took two flights to get

to Florence. I got there at midnight on the Saturday

night. The taxi driver from the airport spoke no

English, but it didn't matter. I love Italians. The man

was only driving the taxi and already I was falling for

everything Florentine.

His aftershave wafted

around the taxi. Delicious. I spotted his silver

identity bracelet and smiled. Driving the taxi looked

like something he did in between romancing all those

women. It was just a hunch I had.

On the Sunday morning I

woke early, worse than a kid on Christmas day. I

wondered if Cura was in the country or was he flying in

that morning. The anticipation of seeing him on stage

was almost too much: that self-assured stride of his;

the smile that he flashes at the audience; the muscles

in his voice.

The opera was on that

afternoon. To distract myself during the long wait I

decided to do the tourist trail: Michelangelo's statue

of David; market stalls brimful of Florentine scarves.

Here was my chance to dress like Sophia Loren. Oddly, I

had no interest. My mind was preoccupied. Every 20

minutes I would look at my watch. Would Cura be arriving

at the theatre? Would he be warming up with the

orchestra? Or would he be doing opera-singer things like

gargling with TCP? Florence was wasted on me. I couldn't

wait to get to the opera.

At lunch time I went back

to my hotel to shower and change. Normally I am thrown

together, but this time I had put thought into my

clothes. My plan was to be subtle and classy. I had

chosen a navy velvet dress, a matching coat and

carefully selected earrings. I put my libretto in my bag

and headed off.

At the Teatro, the ticket

queue was full of well-groomed Italians women with pearl

necklaces, men in exquisitely cut suits. I picked up my

ticket and made my way in. I was 40 minutes early. I

checked out my seat. Had a drink at the bar. Then headed

for the loo for the hundredth time that day. The

excitement was too much.

Eventually the lights went

down. The audience were instructed to turn off their

mobiles. The opera was about to begin. The conductor

made his entrance and began the overture.

THE music was so beautiful.

And I was so happy to be there. I knew that I had done

the right thing. I didn't want to be anywhere else in

the world. Nothing moves the soul like music. Seconds

into the overture, I was crying tears of happiness. The

first aria is sung off-stage by Turiddu (Cura's part).

The minute I heard the voice, I felt uneasy. It didn't

sound like Cura. But maybe that was just because it was

coming from off-stage. I dispelled the doubt.

Another few lines and I

still didn't recognise Cura's voice. Where was that

baritonal quality of his? I was a little worried. But, I

told myself, his name was on the poster outside. Of

course it was him. I sat back and relaxed. Turiddu

wasn't to appear on stage until well into the first act.

I knew the opera backwards.

The set was very beautiful.

The chorus were busy going to church and creating a

village life. It was near the time where Turiddu

appears.

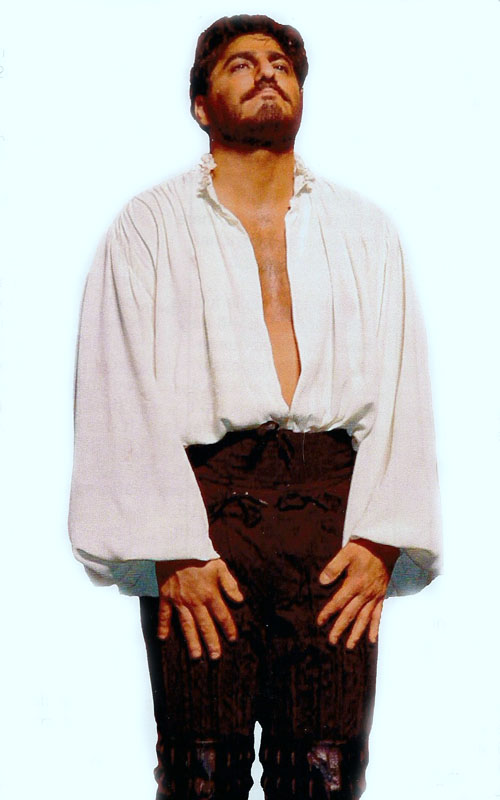

On he came. A squat five

foot nothing of a man with a pot belly. As he walked, he

did so in two parts. His stomach went first and minutes

later the rest of his body caught up. He looked like he

enjoyed his grub. I could almost see the stretch marks

through his white shirt. He had widely-set frog eyes. He

looked a little like Ernest Borgnine. He was no José

Cura. If you didn't laugh, you'd cry.

IF you have never seen a

photo of Cura, you will not understand the full extent

of my tragedy. Cura used to be a body builder. When he

walks onto the stage, he owns it. As he sings, Cura is

full of dramatic feeling. The man is magnificent. A

Greek god. So where the hell was he?

The story of Cavalleria

Rusticana is that Turiddu is the love object. Two

women Santuzza and Lola are clamouring for him. With

Cura as the lead, all that would have made sense. But my

fat frog-eyed puddin', tottering around the stage, made

a mockery of the plot. Oh, yeah, and I think he was

balding too.

At the interval, I asked

the usher about Cura. It had dawned on me that he might

have been sick, that maybe I was watching his stand-in.

But to be honest, I was more concerned with my trekking

all the way to Florence for a day. Instead of a handsome

prince I got to see a pudgy frog. The usher explained

that Cura was finished doing the role. I had missed him

by a matter of days.

It was spilt milk. What

could I do? I sat through the second opera sighing at my

folly.

This is not the first time

I have travelled just to see a beautiful man on stage.

Flying to Florence was a long way to see no José. Maybe

next time I'll travel with the fan club.

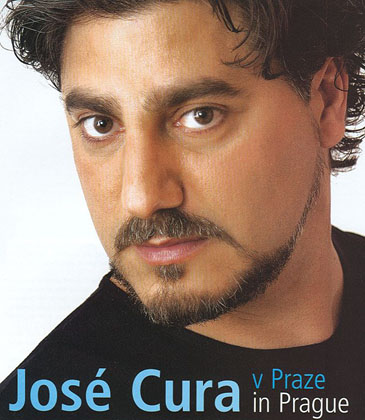

JOSÉ CURA

4th and

5th of August 2000

(temple of Jupiter)

Singer,

composer and conductor, José Cura is considered as one

of the most complete artists of the new generation.

His

Lebanese origin: his great-grand father, Chalita El

Khouri was born in Knet (north Lebanon) in 1874 and his

great grand mother, Teresa Bou Saada was born in Zgharta

in 1881. They arrived in Argentina in 1900.

Since his

debut in the role of Jan in Bibalo’s Fraulein Julie,

his career has taken him to the highest spheres of

the international operatic circuit and to the acclaim

from critics all over the world.

José Cura

was born in Rosario, Santa Fe, Argentina on December 5,

1962. He began his musical formation as a

guitarist under the guidance of maestro Juan di Lorenzo.

At the age of 15 he debuted as a choral conductor. At

16, still in Rosario, he began studying composition with

maestro Carlos Castro and piano with Zulma Cabrera.

In 1982

José Cura entered the School of Arts of the National

University of Rosario in order to develop his knowledge

of orchestra conducting and composition. The following

year, Cura became the assistant to the choir master of

the National University of the Rosario Choir. It

was the choir master, who was also the head of the

conservatory, who convinced Cura to begin studying vocal

technique.

While still

singing in choirs in the mid-eighties, he devoted

himself to composing and conducting. In 1988, he met

maestro Horacio Amauri who gave him the definitive basis

of his singing technique. José Cura left his native

country for Europe in 1991. He lived in Verona Italy for

three years and then in January 1995, he moved to Paris

where he now resides together with his wife and three

children.

In 1992 in

Milan, he met tenor Vittorio Terranova, who has been his

teacher since then and who helped him to master Italian

operatic style. His first professional appearance took

place in an open air concert in Genoa in 1991. In

February 1992, Cura made his stage debut in Verona as

the Father in Henze’s Pollicino . He subsequently

appeared in Genoa as Remendado in Carmen and

Capitano dei Ballestrieri in Simon Boccanegra.

These are the only two "comprimario" roles of his career

so far. Jan in Faulein Julie in March 1993 in

Trieste, was his first major role. In December 1993 he

came to special attention in Turin in Janacek’s

Makropulos Case. Ismaele in Nabucco in

Genoa in January 1994, was his first role in a standard

repertoire opera. After La Forza del Destino in

Turin in February 1994, he sang Ruggero in the world

première of the third version of Puccini’s La Rondine

and in the summer of the same year sang in Martina

Franca in Le Villi, Puccini’s first, rarely

performed opera.

In

September 1994 José Cura won the International

Operalia Competition.

Soon after, he made his

United States debut in Chicago singing Loris Ipanoff in

Giordano’s Fedora. After a Gala Concert in the

Teatro Colon of Buenos Aires, December 1994, he returned

to Italy to sing Paolo il Bello in Zandonai’s

Fancesca da Rimini in Palermo and Fedora in Trieste.

In June 1995, he made his London debut singing the title

role in Stiffelio for the opening night of the

Verdi Festival at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden.

In July 1995, he sang his first Cavaradossi in

Tosca at the Puccini Festival of Torre del Lago

and in September of the same year he made his debut at

the Opera Bastille, singing Ismaele in a new production

of Nabucco. After Fedora in London and

Mascagni’s very rarely performed Iris for the

opening night of the season at the Rome Opera in January

1996. On the 30th of the same month he sang

for the first time the role of Samson in Samson et

Dalila at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. For

his Los Angeles and San Francisco debuts in 1996, he

added two new roles to his repertory, Pollione in

Norma and Don José in Carmen.

Following

Il Corsaro in Turin and Tosca in

London in May 1996, he performed in Melbourne and Sydney

the show "The Puccini Spectacular": 250 artists on stage

for three hours of music, theatre and fireworks

comprising excerpts from the most popular operas of the

Italian composer and specially created for his debut in

Australia. In December 1996, he recorded the BBC

documentary "Great Composers" co-starring Julia Migenes

and Leontina Vaduva. The first episode, devoted to

Giacomo Puccini, was transmitted in December 1997. On

December 22nd, 1996 the Italian TV RAI

transmitted Liliana Cavani’s stage production of

Cavalleria Rusticana starring Waltraud Meier and

José Cura and conducted by Riccardo Muti. The production

was recorded during his debut in the role of Turiddu at

the 1996 Ravenna Festival. Three days later his debut in

I Pagliacci was transmitted on Eurovision live

from Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw. José Cura made his debut

at the Teatro Alla Scala di Milano with Ponchielli’s

La Gioconda, in January 1997. Following his debut in

the title of Otello with the Berlin Philharmonic

Orchestra under Claudio Abbado in May 1997, the

important national newspaper La Nazione headlined

"José Cura : a new Otello is born" and with this

probably best summarized the unanimous praise for the

Argentinian tenor’s assumption of this most testing

role. In June 1997, José Cura received the

Italian Music Critics’ Abbiati award in Italy in the

Category of male singer for his performances in Iris

in Rome, Cavalleria Rusticana in Ravenna, and

Il Corsaro in Turin.

After an

enormously successful Gala Concert in Dublin for

approximately 5000 people he sang Fedora in Lecce

for the 50th anniversary of Umberto

Giordano’s death. On the 22nd of April 1998

he sang Radames in Aida for the official

re-opening of the legendary Teatro Massimo di Palermo .

Recent debuts are

: Opera de Marseille with Don Alvaro in La Forza del

Destino and Des Grieux in Manon Lascaut at La

Scala di Milano.

During

his last German tour in July, he did not only sang but,

for the first time in the history of modern opera, he

also conducted while singing. His recent appearance in

Amsterdam’s Prinsengracht Concert in-front of

20.000 people has also been a big TV event with an

audience of more than 800.000 following-broadcast the

last 22nd of August.

In

coincidence with the release of his recording of

Saint-Saens’ Samson et Dalila, he has done his debut in

Washington on the 10th of November 1998

singing the title role of that opera and on the 25th

of December he sang Luigi in Il Tabarro in a TV

and radio live broadcast from Amsterdam’s Concertgebouw.

After La Forza del Destino, Milano Teatro alla

Scala, February 1999 and his first Andrea Chenier

Zurich, March 1999, he did his home debut in Buenos

Aires, Teatro Colon, with Otello and his

Metropolitan Opera House debut with Cavalleria

Rusticana for the Last Opening Night of the Century

on the 27th of September.

Last

summer, he opened the Arena di Verona Festival with a

new production of Aida which was live broadcasted

on world TV and, for the first time in the history of

opera and transmitted on Internet.

Last

October he sang Otello for his first time ever in

Spain. In December 99, he opened Palermo’s season, also

with Otello. In March 2000, a great event is

marking his career: Placido Domingo, the last of the

greatest Otello, is conducting him in this Verdi

opera in Washington.

1999

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer

it only a a general guide but it should not

be considered definitive.

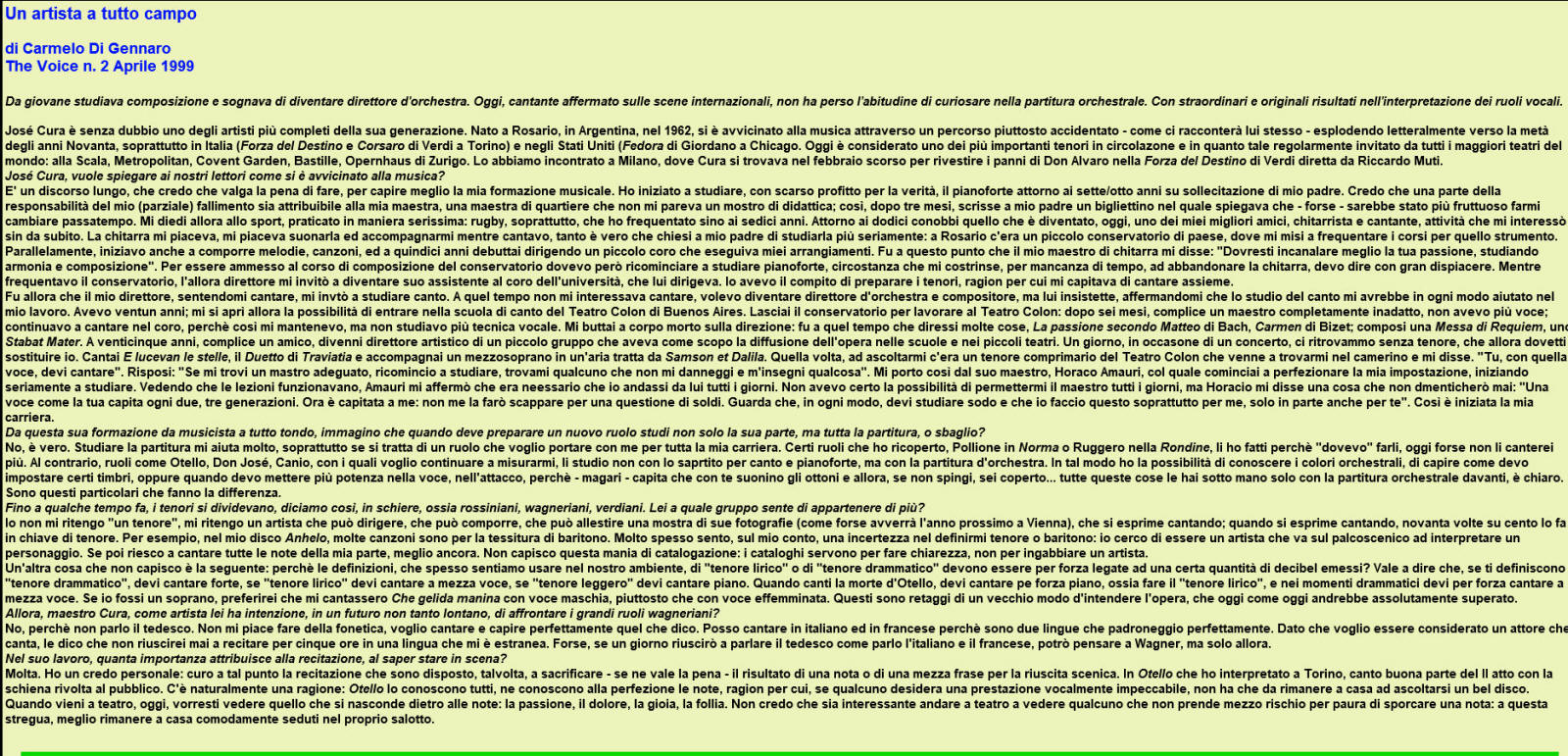

An All-Round Artist

The Voice

Carmelo Di Gennaro

2 April 1999

As

a young man he studied composition and dreamed of becoming a conductor.

Today, an established singer on international stages, he has not

lost the habit of browsing through the orchestral score—with extraordinary

and original results in the interpretation of vocal roles.

José Cura is undoubtedly one of the most complete artists of his

generation. Born in Rosario, Argentina, in 1962, he approached music

through a rather bumpy path—as he himself tells us—literally exploding

in the mid-Nineties, especially in Italy (Verdi’s La forza

del destino and Il Corsaro) and in the

United States (Giordano's Fedora in Chicago).

Today he is considered one of the most important tenors in circulation

and as such is regularly invited by all the major theaters in the

world: La Scala, Metropolitan, Covent Garden, Bastille, Opernhaus

Zurich. We met in Milan, where Cura was in February to play the

role of Don Alvaro in La forza del destino conducted

by Riccardo Muti.

Q: José Cura, would you like to explain to our readers how

you came to music?

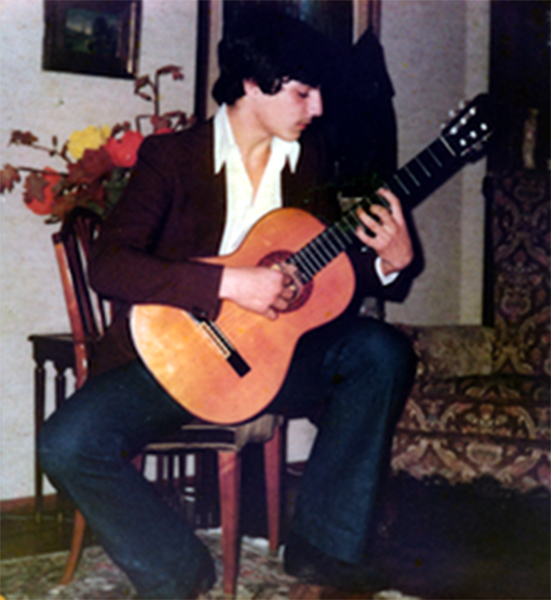

It's a long speech, which I think is worth making, to better

understand my musical training. I began to study, in truth with

little profit, the piano around the age of seven or eight at the

urging of my father. I think that part of the responsibility for

my own (partial) failure is attributable to my teacher, a neighborhood

teacher who did not seem a teaching prodigy; so, after three months,

he wrote my father a note in which he explained that—perhaps—it

would be more fruitful for me to change my hobby. I then immersed

myself in sport, practiced in a very serious way, primarily rugby,

which I played until the age of sixteen. Around the age of twelve

I met someone who has become, today, one of my best friends, a guitarist

and singer, activities that interested me from the beginning. I

liked the guitar. I liked to play it and accompany myself while

I sang, so much so that I asked my father to allow me to study it

more seriously. In Rosario there was a small conservatory, where

I started attending classes for that instrument. At the same time,

I also started to compose melodies and songs, and at fifteen I made

my debut conducting a small choir that performed my arrangements.

It was at this point that my guitar teacher said to me, "You

should channel your passion better, studying harmony and composition."

To be admitted to the composition course of the conservatory, however,

I had to start studying piano again, a circumstance that forced

me, for lack of time, to abandon the guitar, I must say with great

regret. While attending the conservatory, the then director invited

me to become his assistant to the University Choir, which he directed.

I was in charge of preparing the tenors, which is why I happened

to be singing with them.

It was then that my director, hearing me sing, invited me to study

singing. At that time I was not interested in singing. I wanted

to become a conductor and composer but he insisted that the study

of singing would in every way help me in my work. I was twenty-one

years old. Then I was given the opportunity to enter the singing

school at Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires. I left the conservatory

to work at Teatro Colón: after six months, thanks to a completely

unsuitable teacher, I had no voice. I kept singing in the choir,

because that was how I supported myself, but I no longer studied

vocal technique. I threw myself into conducting: it was at that

time that I conducted many things, Bach’s St Matthew Passion,

Bizet’s Carmen. I composed a Requiem mass, a Stabat

Mater. At the age of twenty-five, with a friend, I became the artistic

director of a small group that aimed to spread the work in schools

and small theaters. One day, during a concert, we found ourselves

without tenor, which I then had to replace. I sang E lucevan

le stelle, the duet from La traviata, and accompanied

a mezzo-soprano in an aria taken from Samson et Dalila.

At that time, listening to me was a comprimario tenor from Teatro

Colón who came to see me in the dressing room and said to me. "You,

with that voice, must sing." I replied, "If you find me

a suitable teacher, I'll start studying again. Find me someone

who won't hurt me and who will teach me something." So

I went to his teacher, Horacio Amauri, with whom I began to refine

my approach, starting serious study. Seeing that the lessons were

working, Amauri told me that it was necessary for me to come to

him every day. I certainly couldn’t afford to see a teacher so often

but Horacio told me something that I will never forget: "A

voice like yours happens every two, three generations. Now it happened

to me: I won’t let it go for a matter of money. Look, in any case,

you have to study hard and I am doing this especially for me, only

partly for you, too." That’s how my career began.

Q: From your training as an all-round musician, I imagine

that when you have to prepare a new role you study not only his

part, but the whole score. Am I wrong?

No, it's true. Studying the score helps me a lot, especially

if it is a role that I want to carry with me throughout my career.

Certain roles that I’ve performed, Pollione in Norma

or Ruggero in La rondine, I’ve done because "I

had to" do them. Today I might not sing them again. On

the contrary, roles such as Otello, Don José, Canio, those with

whom I want to continue to measure myself, I study them not with

the score for singing and piano, but with the orchestra score. In

this way I have the chance to get to know the orchestral colors,

to understand how I have to set up some timbres, or when I have

to put more power into the voice, into the attack, because—for example—it

happens that the brass sounds with you, and then, if you don't

push, you're covered... all these things you have in hand only

with the orchestral score in front of you, it's clear. It is

these details that make the difference.

Q: Until recently, tenors were divided, so to speak, into

groups such as Rossinians, Wagnerians, Verdians. In which

group do you feel you belong?

I do not consider myself "a tenor." I consider myself

an artist who can conduct, who can compose, who can set up an exhibition

of his photographs (as perhaps will happen next year in Vienna),

who expresses himself singing. When he expresses himself singing,

ninety times out of a hundred he does it in a tenor key. For example,

in my record Anhelo, many songs are in the tessitura

of a baritone. Very often I feel, on my account, an uncertainty

in defining myself as a tenor or baritone: I try to be an artist

who goes on stage to play a character. If I can sing all the notes

of my part, even better. I do not understand this mania for cataloging:

catalogs are for clarity, not for caging an artist.

Another thing I do not understand is the following: why must the

definitions, which we often hear used in our environment, of "lyric

tenor" or "dramatic tenor" necessarily have to be

related to the certain amount of decibels emitted? That is to say,

if they call you "dramatic tenor," you have to sing loudly,

if "lyrical tenor" you have to sing half-voice, if "light

tenor" you have to sing softly. When you sing the death of

Otello, you have to sing softly, that is, to be the "lyrical

tenor," and in dramatic moments you have to sing half-voice.

If I were a soprano, I'd prefer Che gelida manina sung

with a male voice rather than an effeminate one. These are the legacy

of an old way of understanding opera, which today should absolutely

be overcome.

Q: So, Maestro Cura, as an artist do you intend, in the not so distant

future, to face the great Wagnerian roles?

No, because I don't speak German. I don't like doing phonetics,

I want to sing and understand perfectly what I'm saying. I can

sing in Italian and French because they are two languages that I

perfectly mastered. Since I want to be considered an actor who sings,

I can tell you that I would never be able to act for five hours

in a language that is foreign to me. Perhaps, if one day I can speak

German as I speak Italian and French, I will be able to think of

Wagner, but only then.

Q: In your work, how much importance do you attach to acting, to

being on stage?

A lot. I have a personal belief: I care for the acting to the extent

that I am willing, sometimes, to sacrifice—if it is worth it—the

result of a note or a half sentence for the stage success. In the

Otello I performed in Turin, I sing a good part of the second act

with my back to the audience. There is of course a reason: everyone

knows Otello, they know his notes perfectly, so if someone wants

a vocally impeccable performance, he has only to stay at home to

listen to a beautiful record. When you come to the theater today,

you would like to see what is hidden behind the notes: passion,

pain, joy, madness. I don’t think it is interesting to go to the

theater to see someone who does not take half a risk for fear of

soiling a note. At this point, it is better to stay at home

comfortably sitting in your living room.

|

Fistful of Tenors

The

Irish Times

6

March 1999

Arminta Wallace

A fistful of tenors: Who will be the next ‘big three’?

As the Argentinian singer José Cura returns to Ireland

for the third time, Arminta Wallace finds out who’s

making the most noise in the international tenor stakes.

(excerpts)

Saturday night at the Bastille Opera in Paris, and it’s

show time. Inside the concrete foyer the middle classes

mill about, programmes in hand; outside, Japanese

tourists wearing optimistic smiles and hand-written

“Cherche Billets” signs brave the sharp air of late

maximum chic, and the place is packed to the doors. For

a visiting Paddy, the excitement is palpable-on the

opera thermometer, a new production of Carmen at

one of Europe’s major opera houses has to rate somewhere

between “overheated” and “feverish”.

The moment the curtain rises, however, it becomes

apparent that this production is never going to make it

into the annals of theatre history. We peer in dismay as

interminable chorus lines dressed in 40 shades of brown

repeatedly skip back and forth across a dimly-lit stage.

We fidget discreetly to keep ourselves awake, and are

just beginning to long for a few mantillas and a red

flounce or two when, mid-way through the second act, and

miracle occurs. Carmen’s lover Don José, sung by the

Argentinian tenor José Cura, has taken center stage to

sing La Fleur Que Tu M’avais Jetee – which,

thanks to the seamless beauty of its melody and its

extraordinary pianissimo finish, has become a showpiece

aria. The moment he begins to sing, a profound silence

settles on the audience. All fidgeting ceases. By the

time he reaches the final, anguished “je t’aime”,

Carmen’s is probably the only dry eye in the house. It’s

a miracle, all right – the miracle of a top class tenor

in action.

A beautiful, effortlessly powerful voice; a lithe,

panther-like grace on stage; a commitment to the part so

total that when we go backstage to congratulate him on

his performance, Cura -- though he is, as always, the

epitome of hospitality and charm –- appears drained to

the point of exhaustion. This is what it’s like at the

top of the opera ladder. The rewards are great: so are

the pitfalls. For every tenor who makes it to the top

rung, dozens get stuck on the lower reaches, or fall off

altogether.

But has Cura made it to the very top? And if so, is he

alone there, of is there a plethora of pretenders to the

tenor crown? Over the next few years, will we see the

emergence of “a new three tenors” to replace the unholy

trinity of Domingo, Carreras and Pavarotti, mostly

retired from active service after long and stunningly

successful careers – or is the whole idea just an

outdated marketing notion which will be quietly allowed

to drop by a new generation of intelligent, clued-in

singers? Neil Dalrymple, and agent with the London-based

Music International, has no hesitation in placing José

Cura in the first rank of today’s tenors, along with the

Sicilian-born Roberto Alagna and new boy on the block

Marcelo Alvarez. Below those three, he says, there’s a

major jump downwards to the next level, where he picks

out the Americans Jerry Hadley and Richard Leech, a

Canadian helden-tenor by the name of Richard Margison,

and the Hispanic bel canto trio of Raman Vargas, Luis

Lima and Tito Beltran.

[…]

The Latin American countries are also producing

beautiful, well-trained voices. Cesar Hernandez, from

Puerto Rico, looks a bit like Domingo and has that sort

of sound, and Octavio Arevalo, a young Mexican who just

sang Nemorino for us, will probably be singing at the

Met next season.” Another company which has always

prided itself on nurturing young voices is Welsh

National opera. Isabel Murphy, director of opera

planning at WNO, says her top three tenors would be the

British tenor Ian Bostridge, Roberto Alagna and the

Argentinian Marcelo Alvarez, who recorded his debut CD,

Bel Canto, with WNO last year. “There are some very

interesting young British tenors, too – people like Paul

Charles Clarke who also sings at the Met and around

Europe, or the Welsh singer Gwyn Hughes Jones. Another

exciting British tenor to come on the scene is John

Daszak, who is singing Peter Grimes in our new

production, and has also been booked to do the role at

La Scala in the year 2000.” Such is the perspective from

the opera house. But what about when you walk into a

record shop in search of tenors on disc? Alan Blyth, a

specialist opera reviewer with Gramophone magazine, says

José Cura would be his number one, followed by Roberto

Alagna and Marcelo Alvarez.

“Cura is a very good Samson, as good as we’ve had for

many years, and the performances on his Puccini

Arias disc were very fine...”

[Jonathan Peter] Kenny is himself a tenor buff, with a

considerable collection of historical recordings and a

soft spot for Pavarotti. “He really is wonderful. Of

course he’s such a megastar, he can’t really come on in

an opera without playing the part of Pavarotti – But

he’s still a great singer.

“I first went to see José Cura in Stiffelio

at Covent Garden. It was fantastic. I’d never heard of

him, but he reminded me at once of Giacomo Lauri-Volpi –

it was the vibrato, I think, and also the baritonal

sound which suddenly surprises you by being able to

surge upwards. I like his singing very much – I think

it’s very honest and open and from the heart. Even from

his discs he comes across as a very sincere and truthful

performer.”

“There are far more openings for tenors that for any

other voice in the profession,” says Kenny. “There are

fewer tenors around, and so there are lots of great

roles. But it’s a dangerous profession, being a tenor.

You have to sing in big theatres, before huge audiences,

you have to make a big should and project your voice all

the time. You’ve got to produce the top notes. The money

notes, they call them. But you’ve also got to be careful

because if you spend all your money notes at the

beginning of you career . . ."

It’s a sentence which hardly bears finishing.

And he's not a bad singer. . . . .

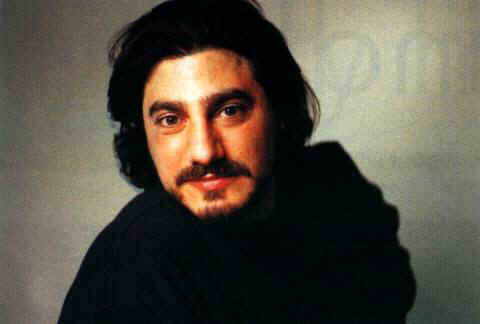

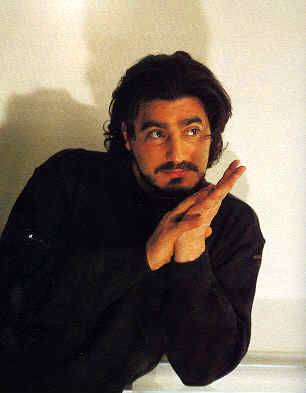

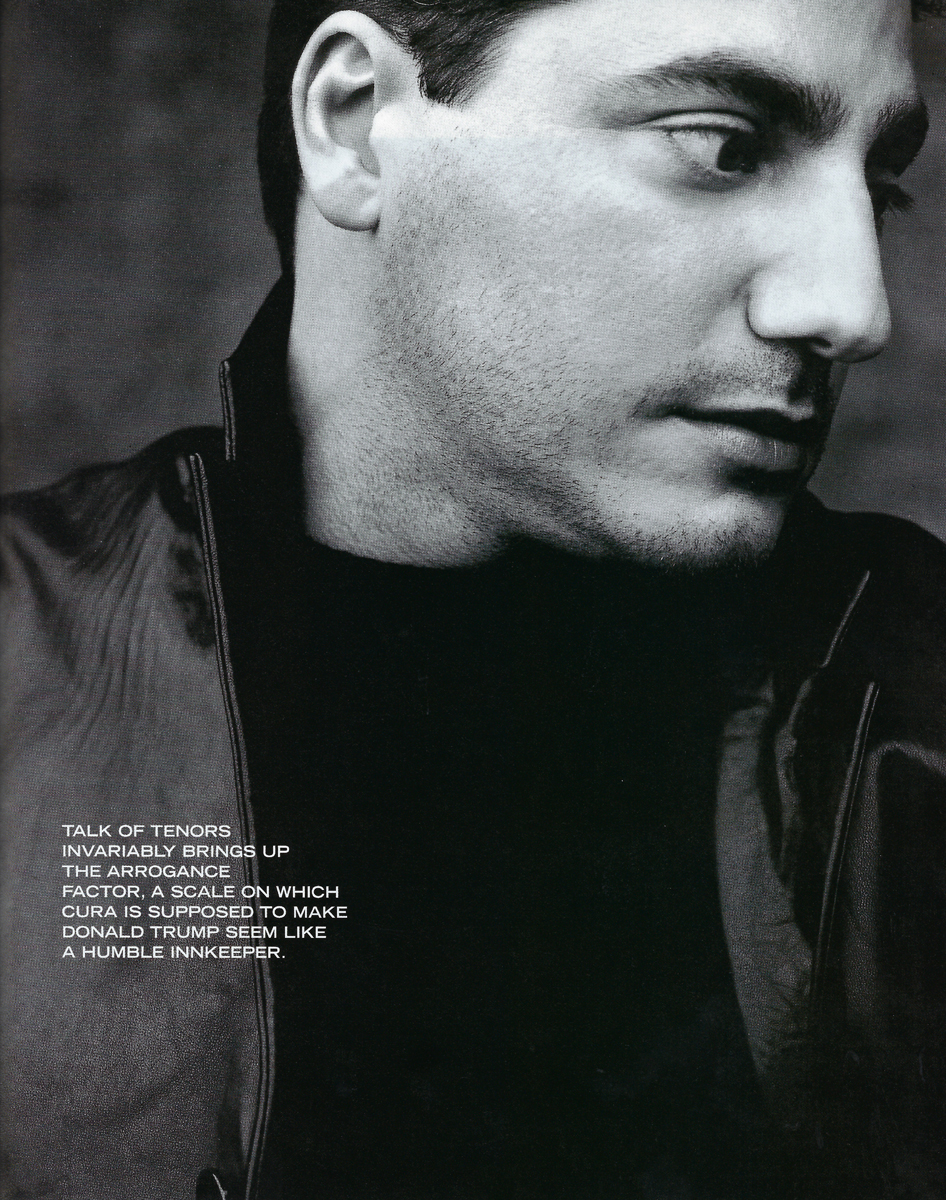

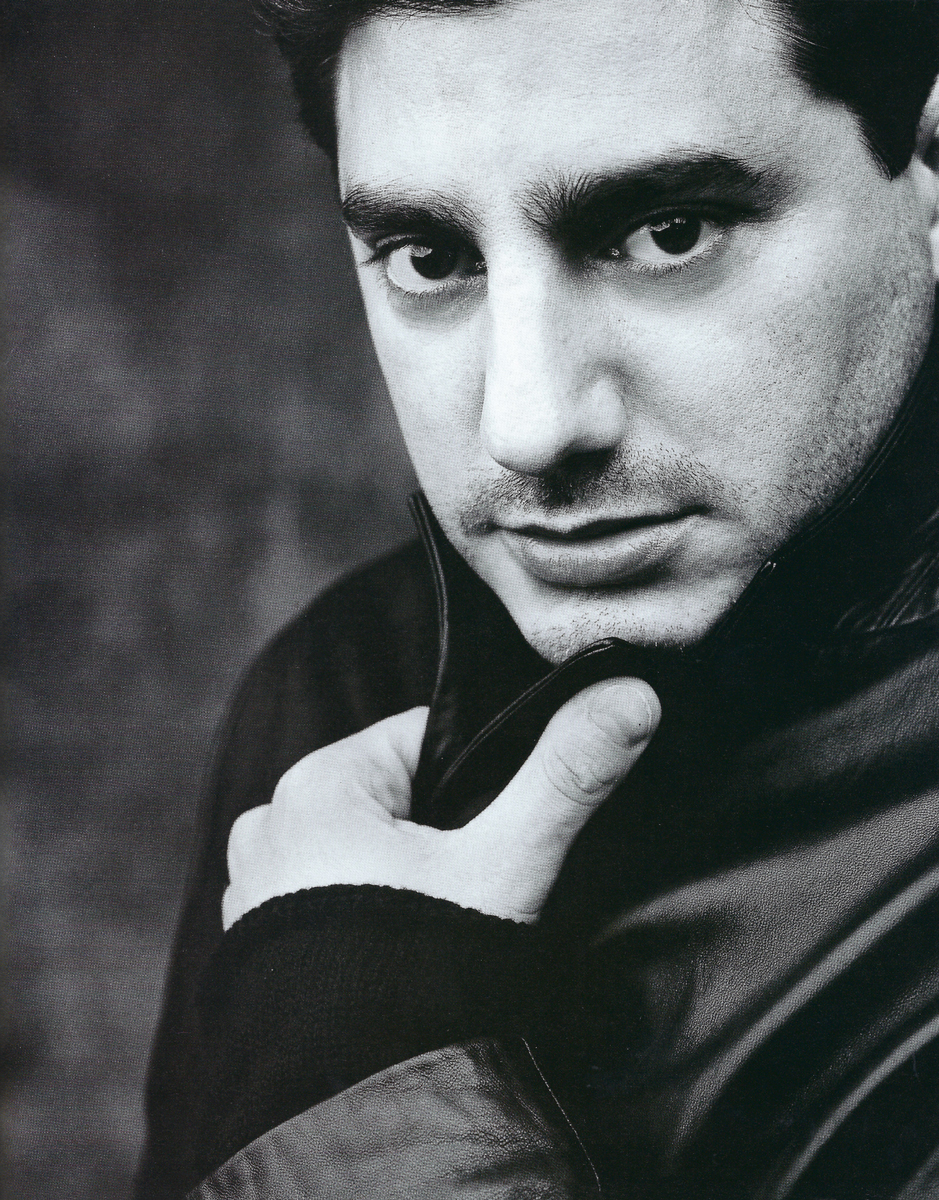

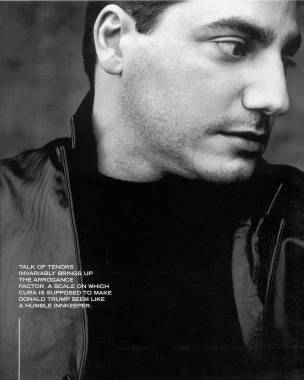

José Cura's good looks are the latest weapon in the

battle to create the next generation of male opera

stars.

The Independent

Anna Picard

05 September 1999

It all started with a woman, a cello and a

chaise-longue: Ofra Harnoy and her instrument locked in

an embrace so intimate, so satisfied, that only the

post-coital cigarettes were missing. Classical music

took longer than most industries to acknowledge the

pulling power of pheromones, but in 1990 - more than 20

years after Jimi Hendrix's Electric Ladyland - it shed

the white tie and started to run, naked, through the

wild woods of mass marketing. From Anne-Sophie Mutter's

bare shoulders to the panda eyes of the Medieval Baebes,

this was the era of the divas.

But what about the men? We had Kennedy's squiggle-like

name-changes and his spiky hair. Simon Rattle had a kind

of hippie chic with his Jackson Five coiffure. But the

singers were lagging behind in the image race - wide of

girth, stiff of stature and woefully straight of dress.

It took a World Cup and a long top B to launch Mr Big

into mass appeal, but Pavarotti took two of his mates

with him. The Three Tenors were (briefly) the Spice

Girls of opera, but even football couldn't really do it

for the primo uomo and sales started to fall again. So

what was left? Sex. It had worked for the girls, after

all.

Italy gave us Andrea Bocelli, the soft-voiced, blind

romantic, and pretty- boy Alagna; but he's very, very

married (to soprano Angela Georghiu) and not terribly

tall. Both Italians are said to stir up "maternal

feelings"; but where do you find an opera singer with a

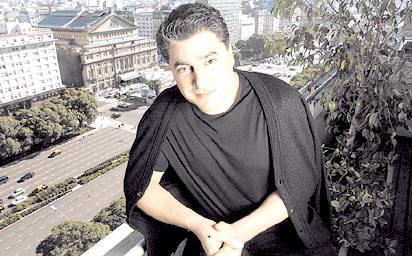

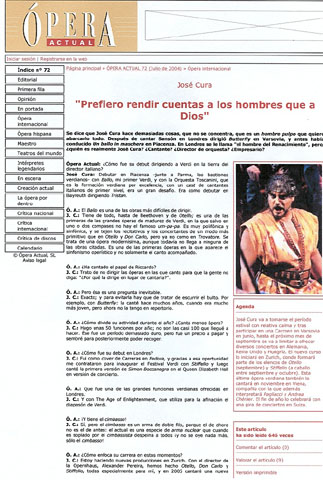

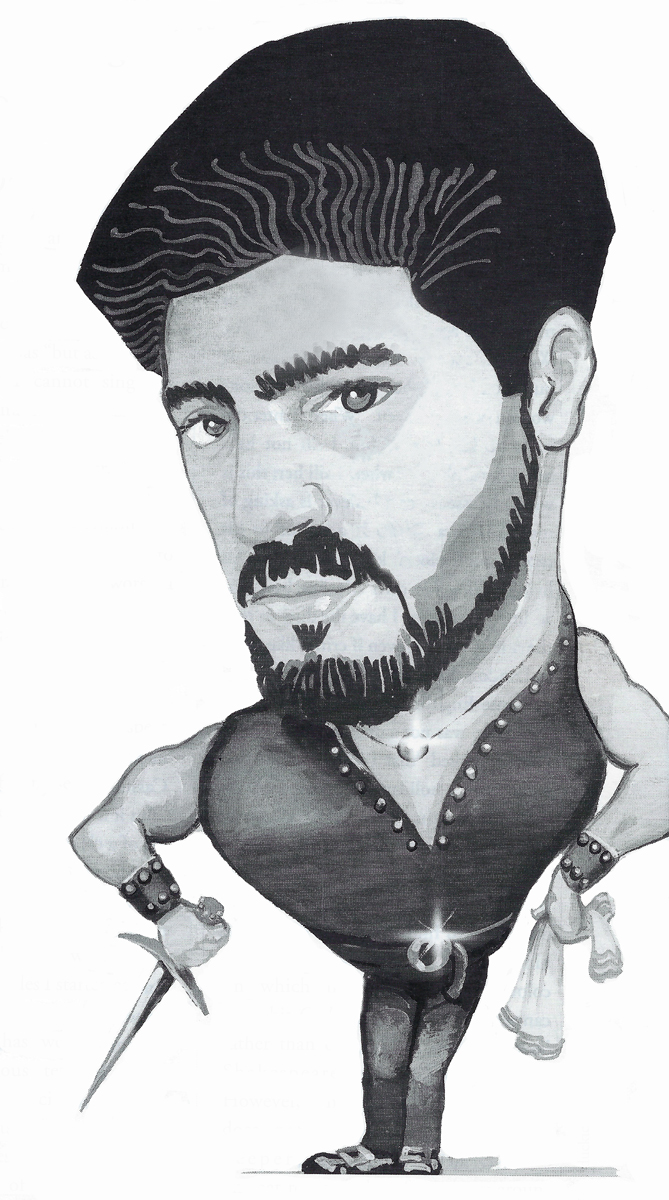

six-pack? Argentina. José Cura, tall, dark and handsome,

a youthful 36 years, a body-builder, a Latin smoothie to

challenge even Antonio Banderas, all the usual interests

(likes football), GSOH (gives bitchy soundbites about

his competitors), tenor, conductor and composer. Cura,

strong of voice, talent and looks, is a miracle drug for

the ailing industry and, according to some, he knows it.

Soon, there will be no getting away from Cura. Next

month he is the subject of a South Bank Show, and

Verismo, his third solo album, a collection of

19th-century Italian tenor standards, is set to be

heavily marketed. Cura's press pack comes complete with

a glossy photo, head inclined downwards like the generic

haircut pictures in a thousand provincial barbershops,

designer stubble, a wolfish grin, and more styling gel

than Ross Geller circa 1995.

But is he sexy? This may seem irrelevant. Surely the

question is "Can he sing?" and yes, he can, but a few

calls to people in various areas of the classical music

industry confirmed that I, my female friends, my gay

male friends and probably my mum too may be the target

audience for tenors.

Traditionally the marketing wisdom has been that women

buy books and men buy CDs. The trouble with classical

music is the repetition of core repertoire, which is

usually already covered in its audience's record

collection. How do you persuade even the most die-hard

opera lover to buy yet another recital disc?

Neil Evans, editor of Classic CD, finds the push for a

new three tenors, or even a fourth one, every

interesting. "I think they're trying to look at a new

market," he says. "Whether it's there or not is

debatable but from the interviews I've seen and from how

they're pushing him, they are big on the macho, moody

figure. Bocelli, Alagna and Cura are certainly being

marketed in terms of mass appeal, in a sexual, romantic

way. There's always been the Mario Lanza type, the

popular light tenor - but Cura is more Clint Eastwood.

"The thing with Cura is he's quite able to acquit

himself with serious opera aficionados as well. I'm a

fan, I'm afraid. I don't feel with him that the

marketing is outstripping his abilities, which you do

get with a lot of musicians. At the end of the day,

whether it's classical music or any other market, the

product has to be good. With José Cura you've got a

genuine talent who combines compelling acting skills, a

wonderful voice and just happens to be highly

marketable."

The record companies admit that good looks help. "Who

would you rather have sing to you?" asked Talia Hull of

Warner Brothers, quite reasonably. But Warner Brothers

and EMI (the company of both Alagna and the pale-

and-interesting Ian Bostridge) deny a conscious move to

hype up the sexiness of their tenors - to women or men.

Bostridge, the most heavily promoted of the young

English tenors, is a curious alternative to the more

obvious va-va-voom of the Latin lover. His career is

built principally on Lieder recitals and relatively

little operatic exposure, so Bostridge's profile has had

to be set in a different niche. EMI's response has been

to have Bostridge loitering diffidently in black

turtle-necks, like an academic Hugh Grant. The company's

uncharacteristically cautious comment on this departure

from glitz and glamour was that Bostridge has "quite a

few female fans".

EMI was recently featured in Private Eye over the

homoerotic photographs of scantily clad "pretty young

things" from its press department that it used to

illustrate Szymanowski's King Roger. But

Theo Lap, EMI's head of marketing, says he is

uninterested in chasing the pink pound. "I don't think

it's necessary. The gay audience and the gay population

will already have a natural interest in classical music.

They always have done, so they're even easier to reach

than other groups. It would be money wasted."

So that's that then? Not according to one record

industry executive, who wished to remain nameless but

who reminded me of the high-camp photo- story that

Vanity Fair ran way back in February 1995 to coincide

with Farinelli, the ultimate castration-anxiety movie.

Six male altos (Chance, Asawa, Gall, Ragin, Minter and

Daniels) were presented in full 18th- century

maquillage, draped across crushed velvet, luxuriantly

lit and photographed by Pascal Chevallier, with the (we

hope) tongue-in-cheek title "The High Boys of Opera".

"It's definitely there in the counter-tenor market," my

source told me. "The packaging of Andreas Scholl's

Heroes CD is disgraceful! You don't need this. Decca is

up to something, and I think it will rebound." Aside

from the allegedly camp portraiture of the (happily

married and stolidly butch) Scholl, the executive

believes that ladies of a certain age are the main

target - 36-plus and Italian-American.

"The men are the thing at the moment," he went on. "In

the 1960s it was the sopranos. These days, basses are

out of it, so it's baritones, which means Dmitri

Hvortovorsky who, if you look at his Phillips covers, is

marketed as the yummy side of Russia, Bryn Terfel - your

original Green Man - and tenors. Tenors have always been

sold on their charm, particularly their Latinate charm.

I don't think anyone tried to sell Pavarotti or Domingo

as sex objects; but women melt when they meet them, they

really do. Alagna is interesting because EMI have tried

to market him-plus-Georghiu as love's young dream. I

think there has definitely been a conscious attempt at

that." So Roberto and Angela are the Tom and Nicole of

opera. What about Cura - does he have what it takes? "Oh

absolutely: (a) he's a very good tenor and (b) he's a

really good musician. Of the younger tenors he is by far

the most complete."

Things bode well for Cura. He has been steadily working

for more than 15 years, and his live performances have

consistently been acclaimed. In addition to the high Cs

he is a competent conductor and a rather good

orchestrator and composer. "It's not Hollywood! I wasn't

discovered overnight in a pizza restaurant!" he snapped

once with a none-too-subtle dig at Alagna's starry-eyed

story. Verismo - operatic for "sh-- happens" - will

probably be that rare beast: a popular success that has

critical backing too.

Though Rodney Milnes of Opera magazine says he finds

Cura's vanity astonishing - referring to his alleged

habit of presenting only his left profile to the camera

- he admits he's "a bloody good singer". Milnes is

unconvinced that the phenomenon of the Three Tenors can

or should ever be repeated. "I don't think it's all that

operatic, honestly. The failure of Turandot at Wembley

proved that. They are two different markets. They're

selling records but they're not necessarily doing the

art of opera any good. Cura is the strongest candidate

for the fourth tenor if there has to be one, because

he's a very good singer. If he does have sex appeal,

then you can't blame the record companies for selling

him that way. He knows it." "There is a definite push

with operatic stuff to appeal to people who want to buy

in a bit of culture, the nouveau riche, the women who

want to buy a little bit of culture for their house,"

added the executive.

José Cura makes his debut at the Met this month

Opera

Rhoda

Koenig

1999

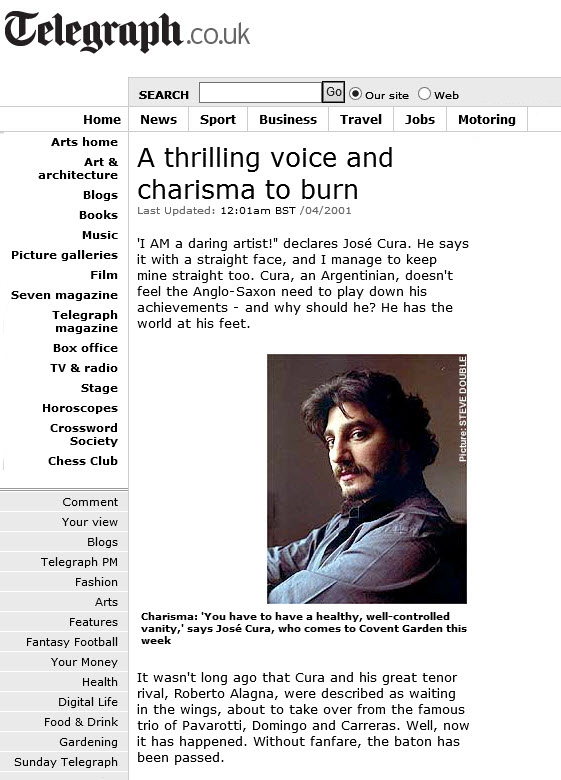

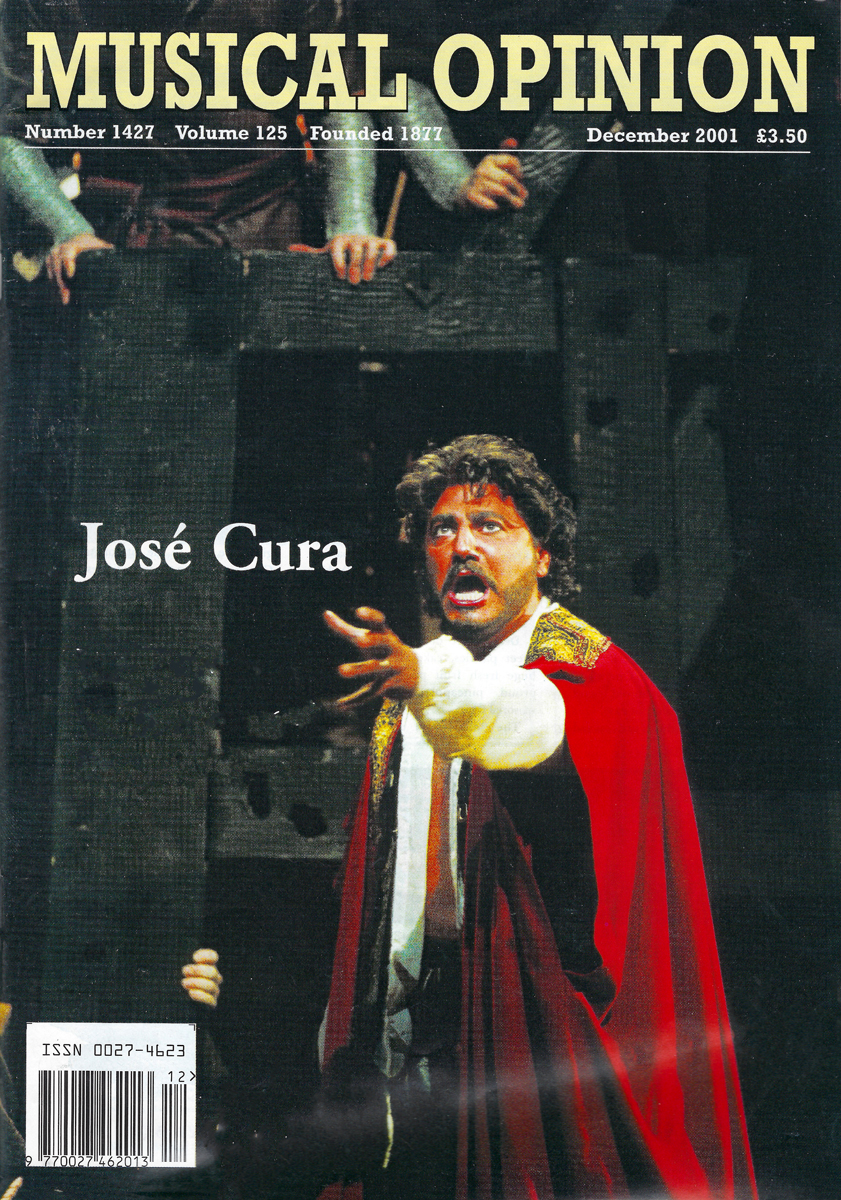

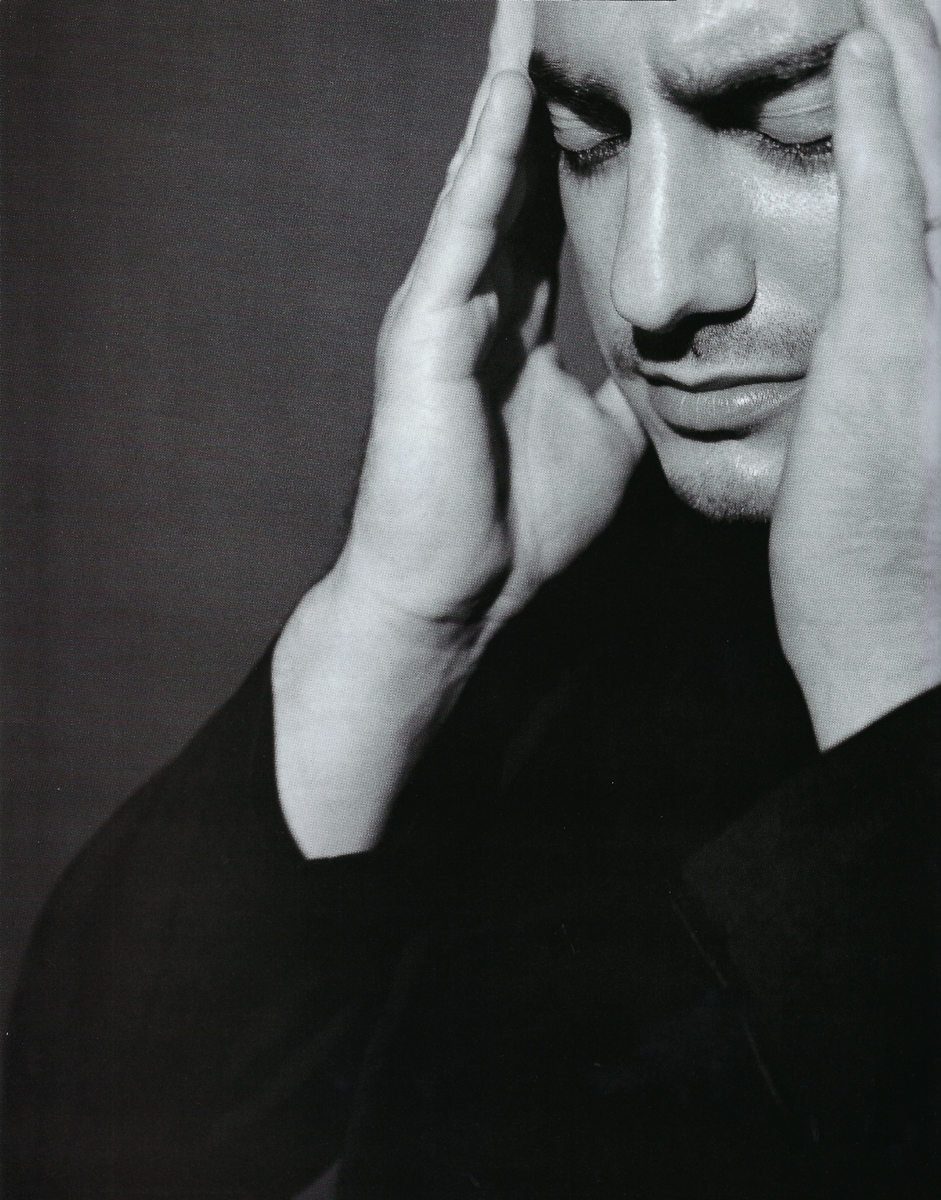

Clutching the air, raging, heartbroken, Otello roars,

“Clamori e canti di battaglia, addio!” and the chic

London audience roars back its rapture. When the

concert performance ends, some of them don’t go home.

Worshipful women of three generation, clutching roses

and photographs (one grandmother is wearing a portrait

on a chain around her neck), wait outside the stage door

for José Cura, a prime slice of Argentine beefcake who

has been wowing the ladies whenever he appears. He

sings all right, too. Even if all you know of opera is

Pavarotti’s singing “Nessun dorma,” you can hear the

difference in the first three notes of Cura’s recording

on his CD of Puccini arias. Instead of a stentorian

declaration, his version is a dark-chocolate

anti-lullaby, the R rolled with a promise and a

threat.

Having triumphed at La Scala and Covent Garden, Cura,

36, will make his Metropolitan Opera debut this month in

Cavalleria rusticana. “It’s a story that could

happen even today,” the tenor says of this tale of

guilty love and bloody vengeance. “Samson, for

instance, [a role Cura has performed and recorded to

acclaim] dies, but he has a victory. But for Turiddu,

there is nothing. This is a really tragic opera.”

Unlike the typical penguin statue in a concert opera,

Cura throws himself into the part – and, of course, does

so even more in a full-dress performance. “To be a

player it is very important to have had a difficult

past. Because then when you have to portray these kind

of human disgraces, you know exactly what you are

talking about.”

Cura’s past was cushy to begin with – he was born into a

wealthy family in Rosario – but when he was eleven, he

and his father were badly injured in a car accident.

The political upheavals of the seventies swept away the

family money and security. But Cura was always

determined to pursue a career in music, at first

composing and conducting. (He continues to do both.

“When I sing I love to perform Verdi, Bellini, Puccini,

but when I write I prefer more contrapuntal music, like

Bach, or satire, like Erik Satie.”)

Though Cura has always been a singer, he decided to

concentrate on the vocal aspect of music only at 26.

Two years later he moved to Italy for its greater

opportunities of work and training, and has steadily

moved up the show-business scale. His wife (he married

at 22) and three children help keep him on an even

kneel, especially since she does not work in the opera.

“Thank God. One crazy person in the family is enough.

Anybody who can stand on the stage and pretend he is

someone else must have folly and the heart of a child in

an iron cage.” Well, that’s one way to put it.

Cura, who performed folk songs as well as opera earlier

this year before an ecstatic Argentine crowd of 40,000,

wants his art to be a popular one, but he is

contemptuous of directors who impose an often alien

relevance on the text. “Bohème is a story of

every day – you can do it in jeans. But if I am going

to do Aida, I want a pyramid and an elephant. I

don’t want to do Aida with a tank. This is not

modernism; this is ridiculism. It is not a word, I

know. But it sounds good.”

Though Cura has been highly praised for his voice and

his acting (compared favorably with Domingo and Gigli)

some critics have called his simultaneous singing and

conducting a silly stunt, or said he is too

narcissistic, too flamboyant. He finds these charges

puzzling. “One critic said, ‘Mr. Cura has to decide

whether he wants to be an opera singer or a sex

symbol.’” Surely he couldn’t deny the latter? (If he

did, the promotional photo of him with soulful gaze and

designer stubble would be evidence against.) “No, no,”

José Cura says, looking hurt. “Why can’t I be both?”

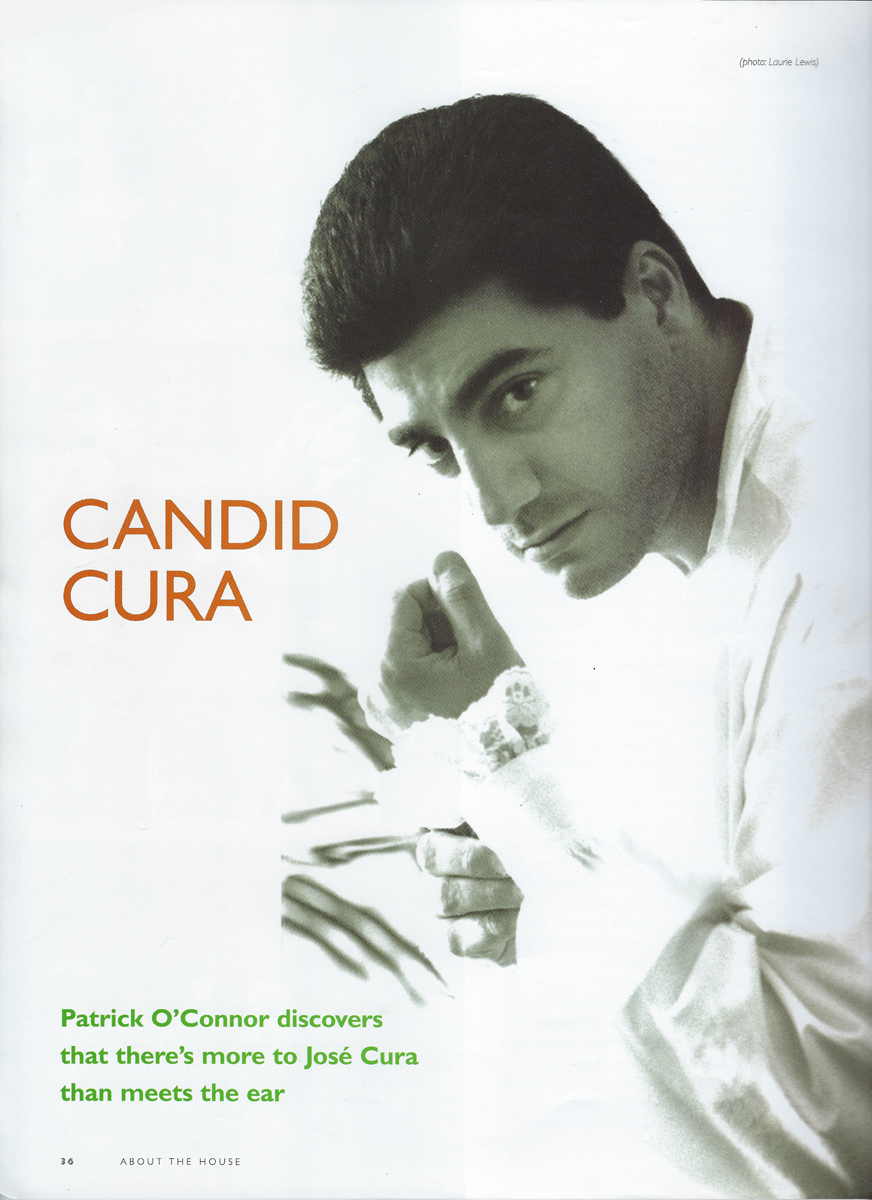

Going Solo: José Cura

A Moor for the Millennium

M. Pappenheim

LSO Living Music

1999

In May, José Cura sings the title role in Verdi’s Otello

in three concert performances with the LSO. The

Argentinian tenor tells Mark Papenheim about the

challenges of a part most singers leave until later in

their careers.

Whatever you do, don’t suggest to José Cura that he is

just an opera singer—or that his career has been a

classic case of overnight success. “I don’t consider

myself to be just a tenor,” he insists, “I consider

myself to be an artist who happens to sing, which is

different...an artist who can also conduct and compose

and take wonderful pictures if he wants to. I’ve been

preparing myself to be what I am today since I first

went on stage at the age of 12. That makes 24 years of

hard work. I don’t think anyone can call that too

quick.”

It is true he combines singing with conducting and

composing—his second recital disc, Anhelo, a

soulful collection of Argentinian songs, includes two of

his own. He has also been a semi-pro athlete, rugby

prop-forward, bodybuilder and Kung Fu black belt. But

it still seems little short of miraculous that, at just

36 and only five years after singing his first major

part in a standard repertory work, Cura has already

notched up another 25 starring roles and sung in most of

the world’s leading theatres, from Covent Garden to

Chicago, via Paris, Vienna and Milan. The statistics

sound even more amazing when you consider that Cura had

never seen an opera before he sang in one himself at the

age of 22. The opera was Massenet’s Manon,

performed at the Teatro Colon in Buenos Aries. As one

of two croupiers in the Act 4 gambling scene, all Cura

had to sing was the phrase “Faites vos jeux,

messieurs! Faites vos Jeux!” (“Place your bets,

gentlemen! Place your bets!”) How many of those

present, I wonder, would have bet money on his chances

of returning to the Teatro Colon this April to star as

Verdi’s Otello - - probably the most challenging and

coveted part in the entire heroic tenor repertoire?

Even four years ago, when Cura made his sensational

London debut with the Royal Opera as Verdi’s

Stiffelio—taking over from José Carreras a part he

would later pass on to Plácido Domingo—I felt I was

sticking my neck out as a music critic when I called him

“an Otello in waiting.” Yet so carefully, so

confidently planned was the course of his ‘overnight’

career that, even then, Cure knew would return to London

this May to sing Verdi’s Moor in concert with Sir Colin

Davis and the LSO.

It was to have been his first attempt at the tenorial

Everest, “in concert, nice and cool and easy, with the

score in front of me, without risk.” But, two years

ago, Cura received an offer he simple could not refuse:

to sing his first Otello on stage, with the Berlin

Philharmonic—under Claudio Abbado, no less—for just two

performances in Turin. After much soul-searching he

accepted, but with one condition: that he would sing

just the two performances and not touch the part again

until 1999, “so as to keep on growing, technically, as

an artist and as an actor.” Despite the avalanche of

faxes which arrived the morning after, the worldwide

offers that could have kept him singing nothing but

Otellos for the rest of his days, Cura stuck to his

guns.

Not that the reception was entirely uncritical. The

Italian national daily La Nazion may have headlined its

review “A new Otello is born,” but some aficionados

thought him too young for the part. Yes, the optimum

age for a tenor to sing Otello may be 45-50, but this

way, when he reaches his prime, he will already have

more than 10 years’ experience under his belt. And

anyway, Domingo, Vickers and Vinay all sang their first

Moors in their thirties. As for it being undersung, “I

can be as loud as I want if I have to. But I don’t

think shouting is the solution to performing this role.”

In fact, the review he liked best was the one that

said: “Cura’s Otello owes more to Orson Welles than to

Mario del Monaco.” That sums up what he was trying to

achieve, he says: his ‘modern vision’ of a bel canto

(rather than verismo) Otello—‘based as much on the

Shakespeare play as on the Verdi opera, in terms of

trying to recreate the last 24 hours of somebody who

used to be a hero but is now breaking into pieces.” If

that annoys ‘conservatives,’ so be it. “When you make

art, you break some rules,” he says. “I think that any

artist who makes everybody happy should be very worried,

because that means he’s not original.”

As for being called ‘The Fourth Tenor,’ Cura admits the

title used to upset him. “They are the old generation—a

wonderful old generation—but we are the new. Only time

will tell what number we will be.” In the meantime, the

LSO can take credit for offering him his first bite at

what looks like being the definitive Otello for the

start of the third millennium.

José Cura

Opera

October 1999

John Allison

(excerpts)

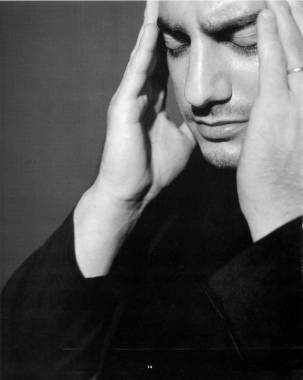

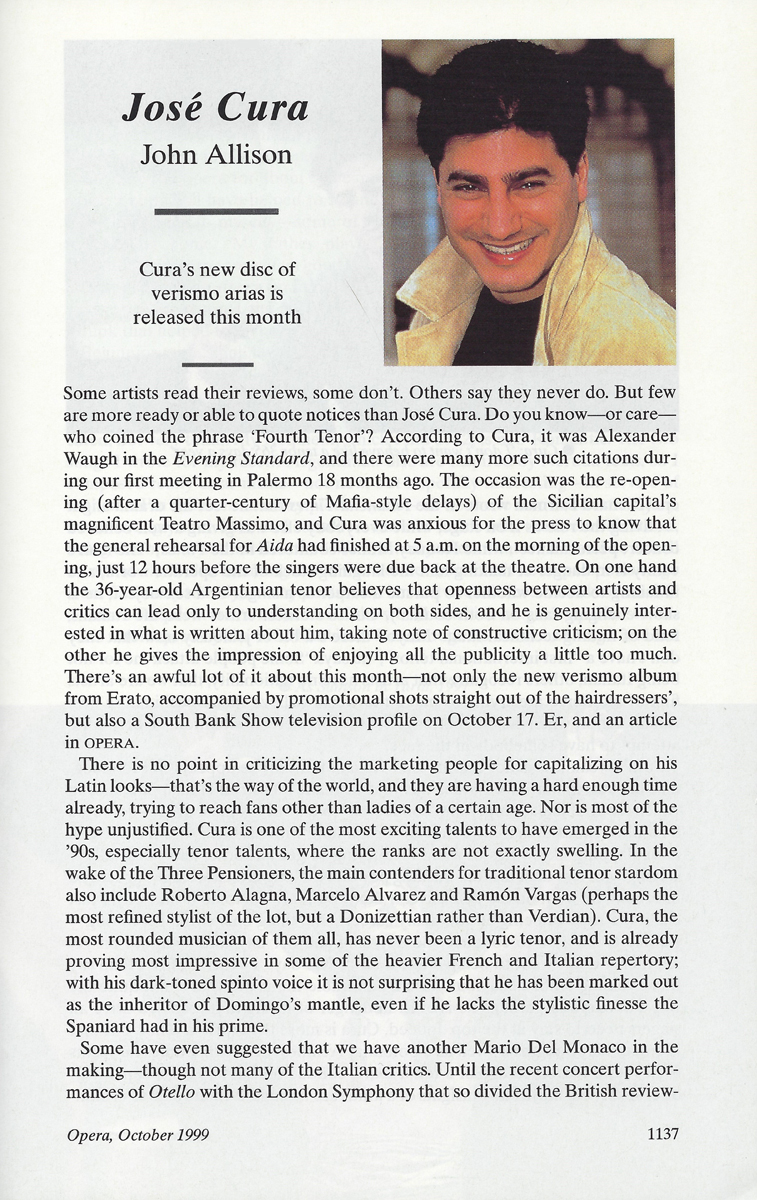

Some artists read their reviews, some don’t. Others say

they never do. But few are more ready or able to quote

notices than José Cura. Do you know – or care – who

coined the phrase ‘Fourth Tenor’? According to Cura, it

was Alexander Waugh in the Evening Standard, and

there were many more such citations during our first

meeting in Palermo 18 months ago. The occasion was the

re-opening (after a quarter-century of Mafia-style

delays) of the Sicilian capital’s magnificent Teatro

Massimo. On one hand the 36-year-old Argentinian tenor

believes that openness between artist and critics can

lead only to understanding on both sides, and he is

genuinely interested in what is written about him,

taking note of constructive criticism; on the other he

gives the impression of enjoying all the publicity.

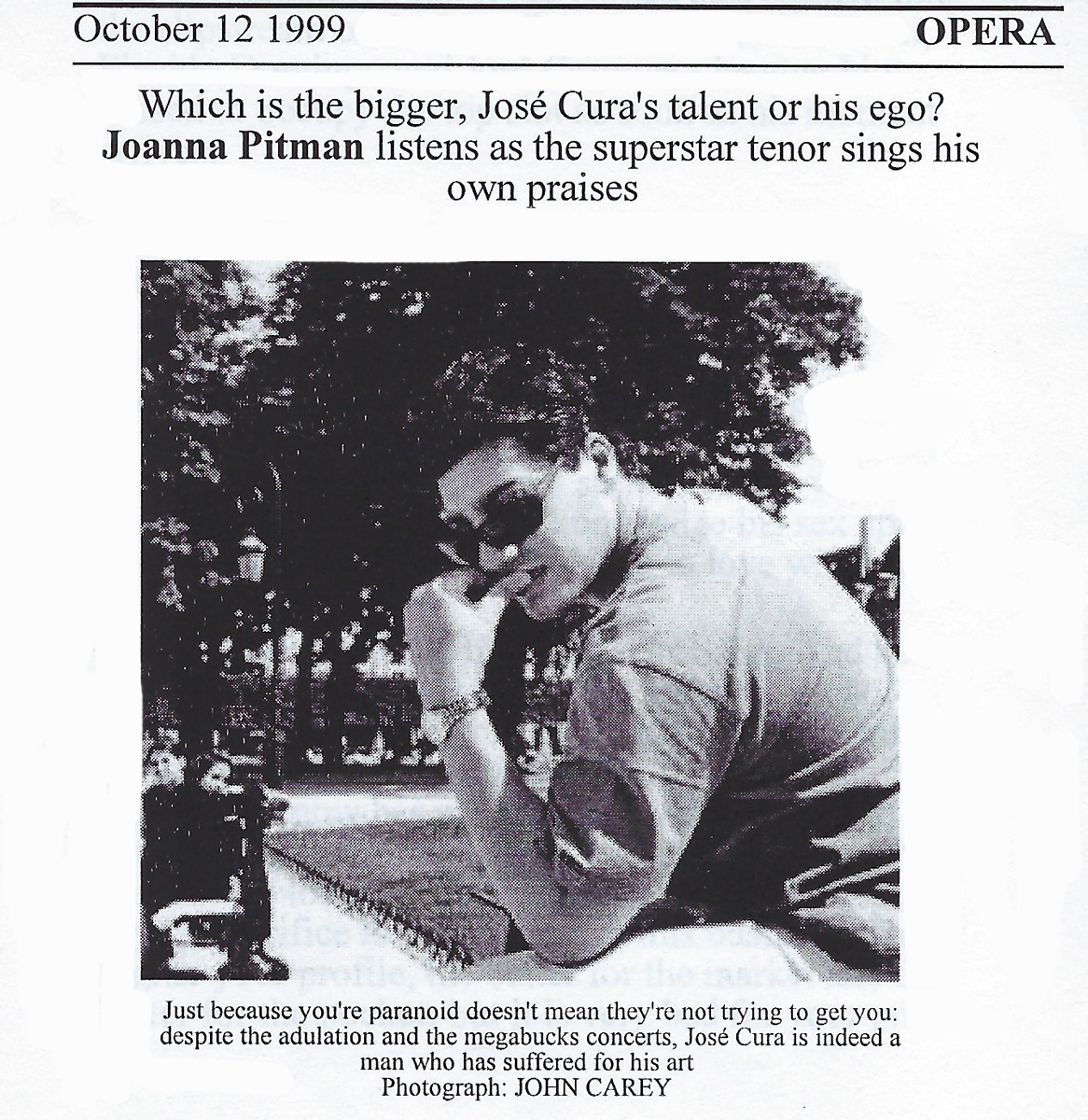

There’s an awful lot of it about this month – not only

the new verismo album from Erato but also a South Bank

Show television profile on October 17. Er, and an

article in OPERA.

There is no point in criticizing the marketing people

for capitalizing on his Latin looks – that’s the way of

the world. Nor is most of the hype unjustified. Cura

is one of the most exciting talents to have emerged in

the ‘90s, especially tenor talents, where the ranks are

not exactly swelling. In the wake of the Three

Pensioners, the main contenders for traditional tenor

stardom also include Roberto Alagna, Marcelo Alvarez and

Ramon Vargas (perhaps the most refined stylist of the

lot, but a Donizettian rather than Verdian). Cura, the

most rounded musician of them all, has never been a

lyric tenor, and is already proving most impressive in

some of the heavier French and Italian repertory; with

his dark-toned spinto voice it is not surprising that he

has been marked out as the inheritor of Domingo’s

mantle, even if he lacks the stylistic finesse the

Spaniard had in his prime.

Some have even suggested that we have another Mario Del

Monaco in the making – though not many of the Italian

critics. Until the recent concert performances at

Otello with the London Symphony that so divided the

British reviewers (Richard Fairman wrote in the

Financial Times that he ‘set the drama alight…living

the role as if on stage, while everybody else was giving

a well-behaved concert performance’, while Rodney Milnes

countered in the Times, ‘The man’s vanity is in

danger of making him the laughing stock of the operatic

world, and in failing to decide whether to pursue a

career as a singer or a sex-object, he is short-changing

fans on both counts’), Cura’s sternest critics were the

Italians, fond of finding technical fault. ‘Maybe

there’s a bit of jealously now that they don’t have a

“first international tenor”,’ he says. ‘Some people

attack me for not being Italian, others recognize that

artists have no nationality, that we are artists first

of all. Some are trying to make the world believe that

Bocelli is the best Italian tenor. It’s a commercial

situation, a desperate attempt to have somebody in the

race.’

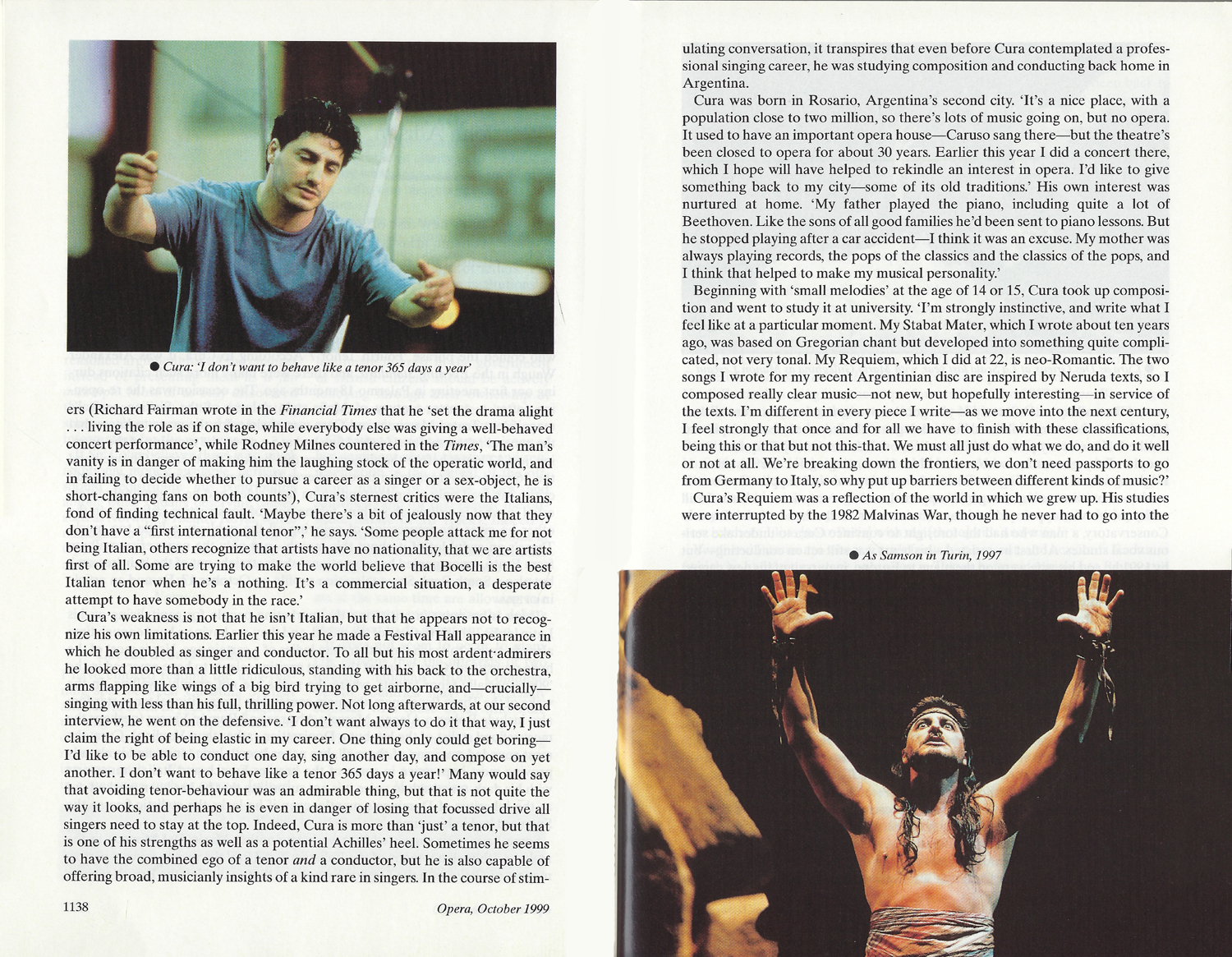

[...]

Indeed, Cura is more than ‘just’ a tenor, but that is

one of his strengths as well as a potential Achilles’

heel. Sometimes he seems to have the combined ego of a

tenor and a conductor, but he is also capable of

offering broad, musicianly insights of a kind rare in

singers. In the course of stimulating conversation, it

transpires that even before Cura contemplated a

professional singing career, he was studying composition

and conducting back home in Argentina.

Cura was born in Rosario, Argentina’s second city.

‘It’s a nice place, with a population close to two

million, so there’s lots of music going on, but no

opera. It used to have an important opera house –

Caruso sang there – but the theatre’s been closed to

opera for about 30 years. Earlier this year I did a

concert there, which I hope will have helped to rekindle

an interest in opera. I’d like to give something back

to my city – some of its old traditions’. His own

interest was nurtured at home. ‘My father played the

piano, including quite a lot of Beethoven. Like the

sons of all good families he’d been sent to piano

lessons. But he stopped playing after a car accident –

I think it was an excuse. My mother was always playing

records, the pops of the classics and the classics of

the pops, and I think that helped to make my musical

personality.’

Beginning with ‘small melodies’ at the age of 14 or 15,

Cura took up composition and went to study it at

university. ‘I’m strongly instinctive, and write what I

feel like at a particular moment. My Stabat Mater,

which I wrote about ten years ago, was based on

Gregorian chant but developed into something quite

complicated, not very tonal. My Requiem, which I did at

22, is neo-Romantic. The two songs I wrote for my

recent Argentinian disc are inspired by Neruda texts, so

I composed really clear music – not new, but hopefully

interesting – in service of the texts. I’m different in

every piece I write – as we move into the next century.

I feel strongly that once and for all we have to finish

with these classifications, being this or that but not

this-that. We must all just do what we do, and do it

well or not at all. We’re breaking down the frontiers,

we don’t need passports to go from Germany to Italy, so

why put up barriers between different kinds of music’

Cura’s Requiem was a reflection of the world in which we

grew up. His studies were interrupted by the 198

Malvinas War, though he never had to go into the army.

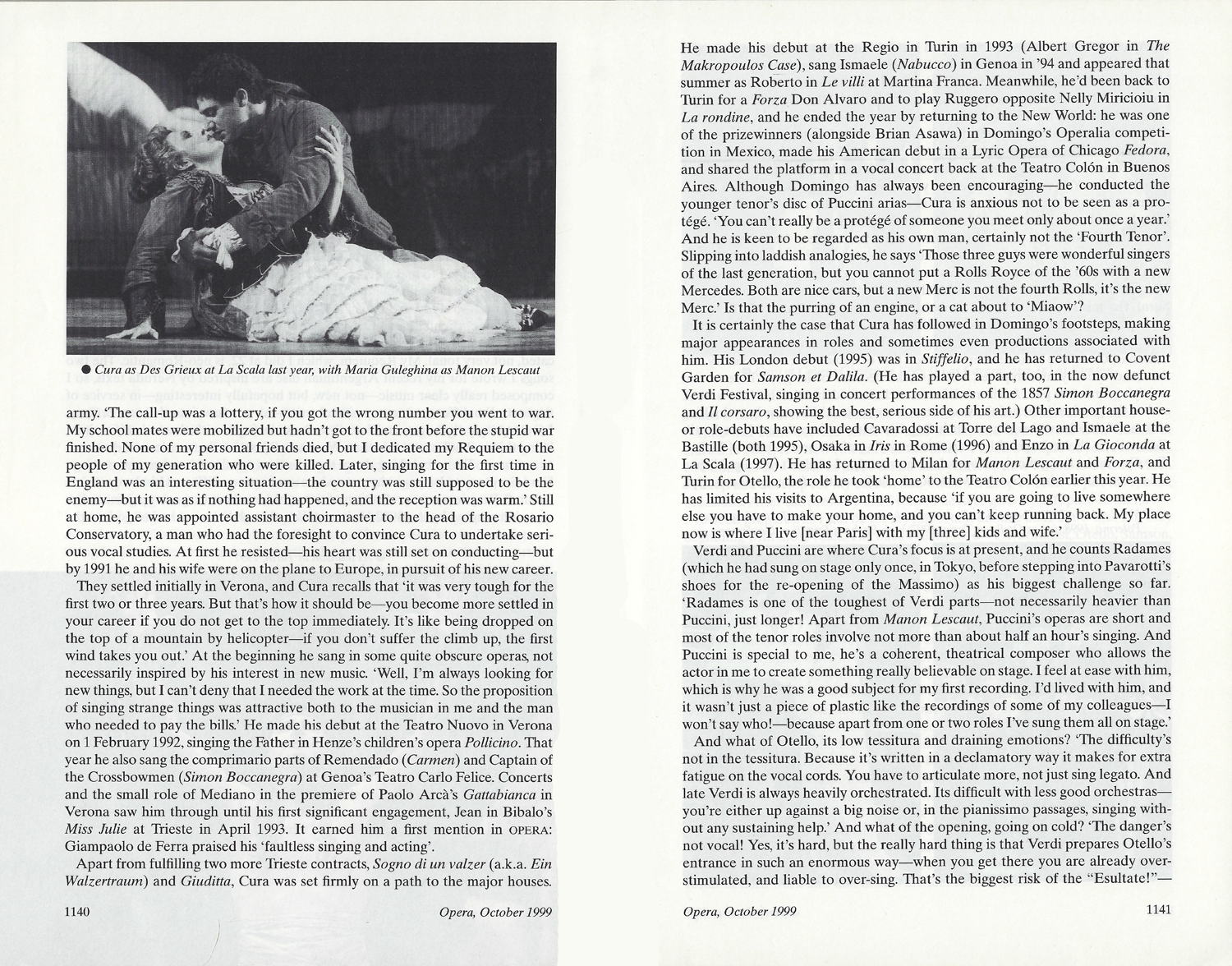

‘The call-up was a lottery, if you got the wrong number

you went to war. My schoolmates were mobilized but

hadn’t got to the front before the stupid war finished.

None of my personal friends died, but I dedicated my

Requiem to the people of my generation who were killed.

Later, singing for the first time in England was an

interesting situation – the country was still supposed

to be the enemy – but it was as if nothing had happened,

and the reception was warm.’ Still at home, he was

appointed assistant choirmaster to the head of the

Rosario Conservatory, a man who had the foresight to

convince Cura to undertake serious vocal studies. At

first he resisted – his heart was still set on

conducting – but by 1991 he and his wife were on the

plane to Europe, in pursuit of his new career.

They settled initially in Verona, and Cura recalls that

‘it was very tough for the first two or three years.

But that’s how it should be – you become more settled in

your career if you do not get to the top immediately.

It’s like being dropped on the tope of a mountain by a

helicopter – if you don’t suffer the climb up, the first

wind takes you out.’ At the beginning he sang in some

quite obscure operas, not necessarily inspired by his

interest in new music. ‘Well, I’m always looking for

new things, but I can’t deny that I needed the work at

the time. So the proposition of singing strange things

was attractive both to the musician in me and the man

who needed to pay the bills.’ He made his debut at the

Teatro Nuovo in Verona on 1 February 1992, singing the

Father in Henze’s children’s opera Pollicino.

That year he also sang the comprimario parts of

Remendado (Carmen) and Captain of the Crossbowmen

(Simon Boccanegra) at Genoa’s Teatro Carlo

Felice. Concerts and the small role of Mediano in the

premiere of Paolo Arca’s Gattabianca in Verona

saw him through until his first significant engagement,

Jean in Bibalo’s Miss Julie at Trieste in April

1993. It earned him a first mention in OPERA: Giampaolo

de Ferra praised his ‘faultless singing and acting’.

Apart from fulfilling two more Trieste contracts,

Sogno di un valzer (a.k.a. Ein Walzertraum)

and Giuditta, Cura was set firmly on a path to

the major houses. He made his debut at the Regio in

Turin in 1993 (Albert Gregor in The Makropoulos Case),

sang Ismaele (Nabucco) in Genoa in ’94 and

appeared that summer as Roberto in Le Villi at

Martina Franca. Meanwhile, he’d been back to Turin for

a Forza Don Alvaro and to play Ruggero opposite

Nelly Miricioiu in La Rondine, and he ended the

year by returning to the New World; he was one of the

prizewinners (alongside Brian Asawa) in Domingo’s

Operalia competition in Mexico, made his American debut

in a Lyric Opera of Chicago Fedora, and shared

the platform in a vocal concert back at the Teatro Colon

in Buenos Aires. Although Domingo has always been

encouraging – he conducted the younger tenor’s disc of

Puccini arias – Cura is anxious not to be seen as a

protégé. ‘You can’t really be a protégé of someone you

meet only about once a year.’ And he is keen to be

regarded as his own man, certainly not the ‘Fourth

Tenor’. Slipping into laddish analogies, he says ‘Those

three guys were wonderful singers of the last

generation, but you cannot put a Rolls Royce of the ‘60s

with a new Mercedes. Both are nice cars, but a new Merc

is not the fourth Rolls, it’s the new Merc.’

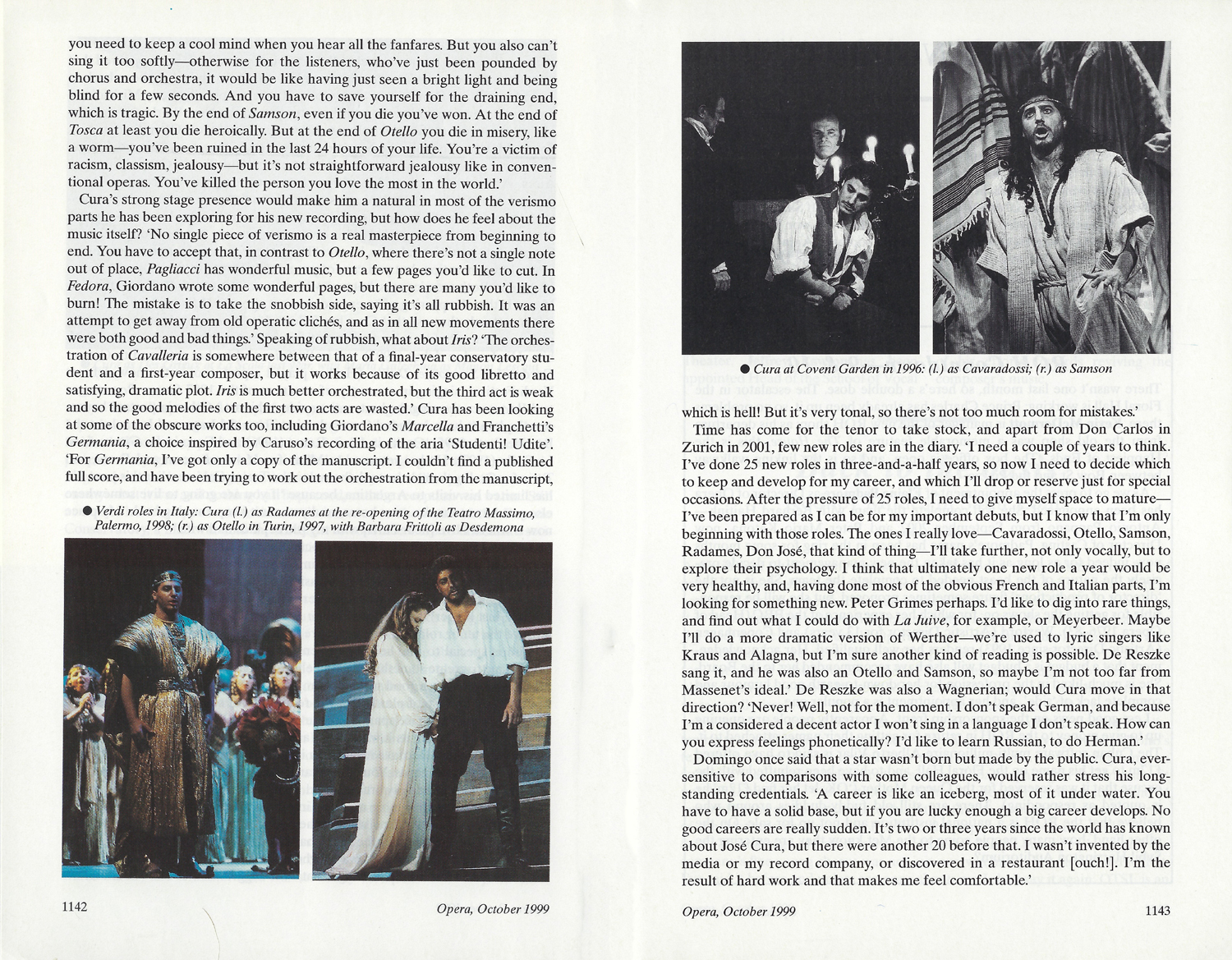

It is certainly the case that Cura has followed in

Domingo’s footsteps, making major appearances in roles

and sometimes even productions associated with him. His

London debut (1995) was in Stiffelio, and he has

returned to Covent Garden for Samson et Dalila.

(He played a part, too, in the now defunct Verdi

Festival, singing in concert performances of the 1857

Simon Boccanegra and Il Corsaro, showing the

best, serious side of his art.) Other important

house-or role-debuts have included Cavaradossi at Torre

del Lago and Ismaele at the Bastille (both 1995), Osaka

in Iris in Rome (1996) and Enzo in La Gioconda

at La Scala (1997). He has returned to Milan for

Manon Lescaut and Forza, and Turin for

Otello, the role he took ‘home’ to the Teatro Colon

earlier this year. He has limited his visits to

Argentina, because ‘if you are going to live somewhere

else you have to make your home, and you can’t keep

running back. My place now is where I live [near Paris]

with my [three] kids and wife.’

Verdi and Puccini are where Cura’s focus is at present,

and he counts Radames (which he had sung on stage only

once, in Tokyo, before stepping into Pavarotti’s shoes

for the re-opening of the Massimo) as his biggest

challenge so far. ‘Radames is one of the toughest of

Verdi parts – not necessarily heavier than Puccini, just

longer! Apart from Manon Lescaut, Puccini’s

operas are short and most of the tenor roles involve not

more than about half an hour’s singing. And Puccini is

special to me, he’s a coherent, theatrical composer who

allows the actor in me to create something really

believable on stage. I feel at ease with him, which is

why he was a good subject for my first recording. I’d

lived with him, and it wasn’t just a piece of plastic

like the recording because apart from one or two roles

I’ve sung them all on stage.’

And what of Otello, its low tessitura and draining

emotions? ‘The difficulty’s not in the tessitura.

Because it’s written in a declamatory way it makes for

extra fatigue on the vocal chords. You have to

articulate more, not just sing legato. And late Verdi

is always heavily orchestrated. Its difficult with less

good orchestras – you’re either up against a big noise

or, in the pianissimo passages, singing without any

sustaining help.’ And what of the opening, going on

cold? ‘The danger’s not vocal! Yes, it’s hard, but the

really hard thing is that Verdi prepares Otello’s

entrance in such an enormous way – when you get there

you are already over-stimulated, and liable to

over-sing. That’s the biggest risk of the “Esultate!” –

you need to keep a cool mind when you hear all the

fanfares. But you also can’t sing it too softly –

otherwise for the listeners, who’ve just been pounded by

chorus and orchestra, it would be like having just seen

a bright light and being blind for a few seconds. And

you have to save yourself for the draining end, which is

tragic. By the end of Samson, even if you die

you’ve won. At the end of Tosca at least you die

heroically. But at the end of Otello you die in

misery, like a worm – you’ve been ruined in the last 24

hours of your life. You’re a victim of racism,

classism, jealousy – but it’s not straightforward

jealousy like in conventional operas. You’ve killed the

person you love the most in the world.’

Cura’s strong stage presence would make him a natural in

most of the verismo parts he has been exploring for his

new recording, but how does he feel about the music

itself? ‘No single piece of verismo is a real

masterpiece from beginning to end. You have to accept

that, in contrast to Otello, where there’s not a

single note out of place, Pagliacci has wonderful

music, but a few pages you’d like to cut. In Fedora,

Giordano wrote some wonderful pages, but there are many

you’d like to burn! The mistake is to take the snobbish

side, saying it’s all rubbish. It was an attempt to get

away from old operatic clichés, and as in all new

movements there were both good and bad things.’

Speaking of rubbish, what about Iris? ‘The

orchestration of Cavalleria is somewhere between

that of a final-year conservatory student and a

first-year composer, but it works because of its good

libretto and satisfying, dramatic plot. Iris is

much better orchestrated, but the third act is weak and

so the good melodies of the first two acts are wasted.’

Cura has been looking at some of the obscure works too,

including Giordano’s Marcella and Franchetti’s

Germania, a choice inspired by Caruso’s recording of

the aria ‘Studenti! Udite’. ‘For Germania, I’ve

got only a copy of the manuscript. I couldn’t find a

published full score, and have been trying to work out

the orchestration from the manuscript, which is hell!

But it’s very tonal, so there’s not too much room for

mistakes.’

Time has come for the tenor to take stock, and apart

from Don Carlos in Zurich in 2001, few new roles

are in the diary. ‘I need a couple of years to think.

I’ve done 25 new roles in three-and-a-half years, so now

I need to decide which to keep and develop for my

career, and which I’ll drop or reserve just for special

occasions. After the pressure of 25 roles, I need to

give myself space to mature – I’ve been prepared as I

can be for my important debuts, but I know that I’m only

beginning with those roles. The ones I really love –

Cavaradossi, Otello, Samson, Radames, Don José, that

kind of thing – I’ll take further, not only vocally, but

to explore their psychology. I think that ultimately

one new role a year would be very healthy, and, having

done most of the obvious French and Italian parts, I’m

looking for something new. Peter Grimes perhaps. I’d

like to dig into rare things, and find out what I could

do with La Juive, for example, or Meyerbeer.

Maybe I’ll do a more dramatic version of Werther – we’re

used to lyric singers like Kraus and Alagna, but I’m

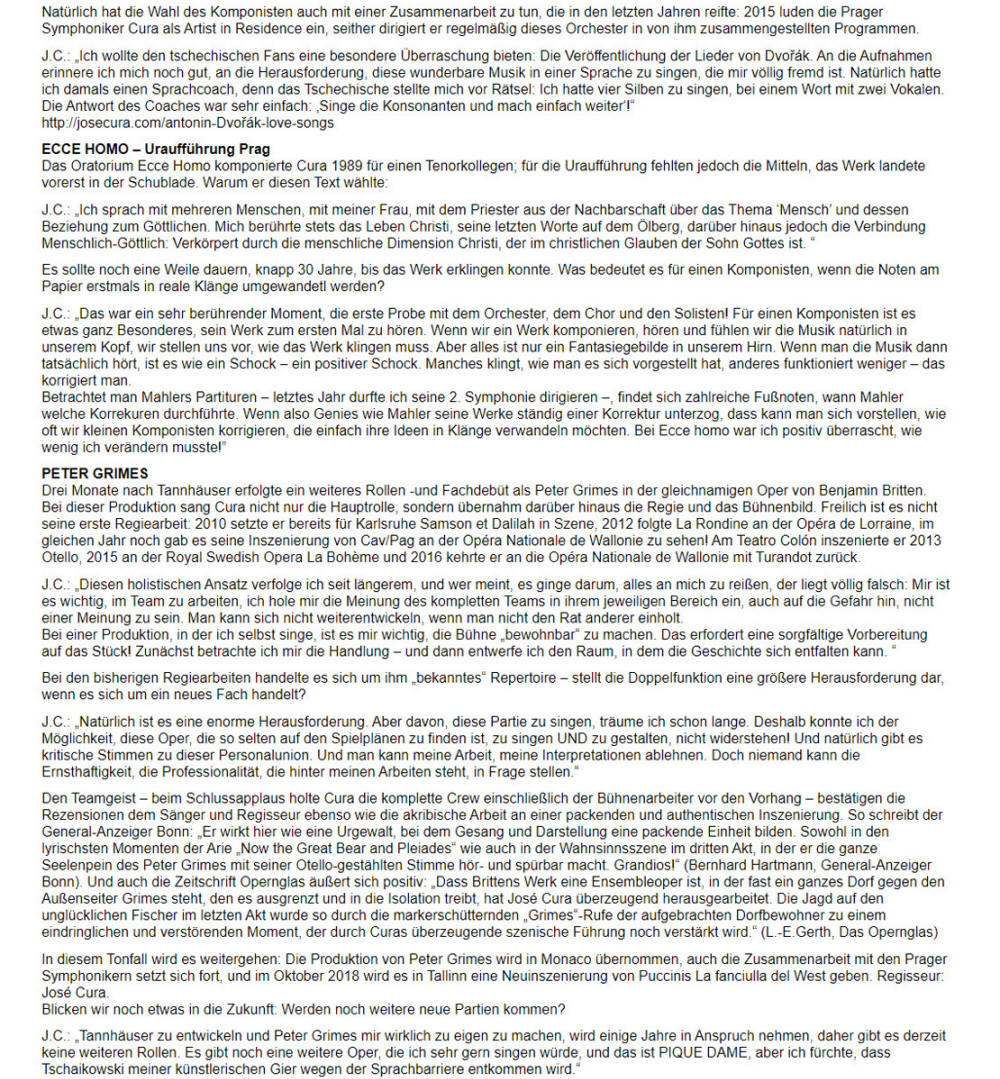

sure another kind of reading is possible. De Reszke