|

|

|

|

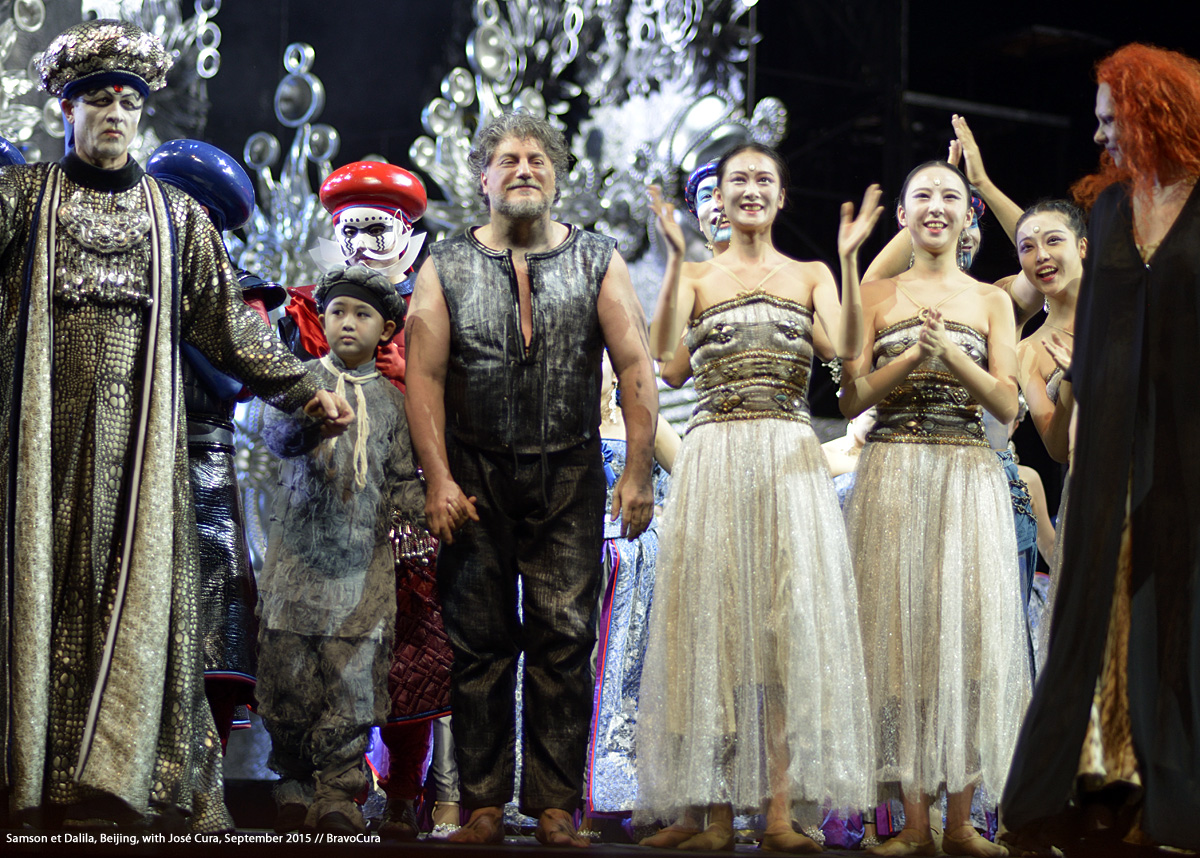

It took a while but we finally finished the retrospective on Samson in Beijing -- it's not easy to work through the differences in languages and collating all the various photos and articles. It was a special production but we'll admit getting around in Beijing wasn't easy and there were lots of restrictions on what you could do inside the venue. The production itself was abstract and at times nonsensical and we weren't sure if the opera-going Chinese were familiar with the surreal approach or this would be something that they might find challenging. (If it counts--we found it pretty challenging.) Still, it was a great experience. We are off for our summer vacation starting mid-week so we won't be updating Bravo Cura until some time in July. Until then, enjoy the summer. |

Tickets are now available

Peter Grimes - Estonia National Opera

Samson et Dalila in Beijing

Samson et Dalila

in

Beijing

9, 11 & 13 September 2015

Opera House of National Grand Theatre

Note: This is a computer generated translation that includes comments from José Cura. Cura uses words with precisions and imagery to effect. The computer does neither.

After Playing the Abject Hero for Twenty Years, He Remains the Versatile King of Tenors

SoHu Business

8 September 2015

[Excerpts]

Pavarotti, Domingo and Carreras formed the “Three Tenors” in the 1970s and became an enormous global sensation. With the death of Luciano Pavarotti and with Plácido Domingo and José Carreras gradually shifting to baritone and concert stage, respectively, the era of the “Three Tenors” is gone, though people continue to seek the magnificent and penetrating voice to succeed them. But the emergence of a leading tenor is a rare thing, since the tenor voice is not a natural sound; as a result, they enjoy a higher status—and compensation—than sopranos.

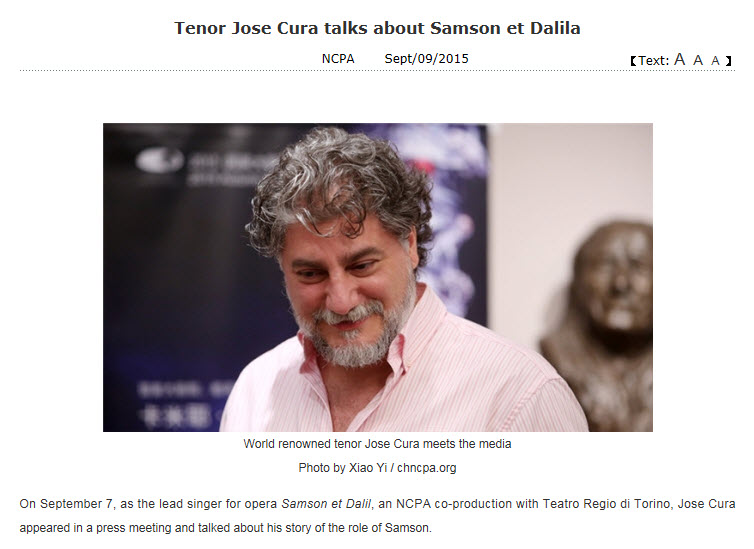

Among the many active tenors on the stage today, Argentine tenor José Cura arrived with great expectations. In the early 1990s the British media praised him as “the brightest star in the tenor sky.” Although Cura didn’t care for the term, people referred to him as the “Fourth tenor.”

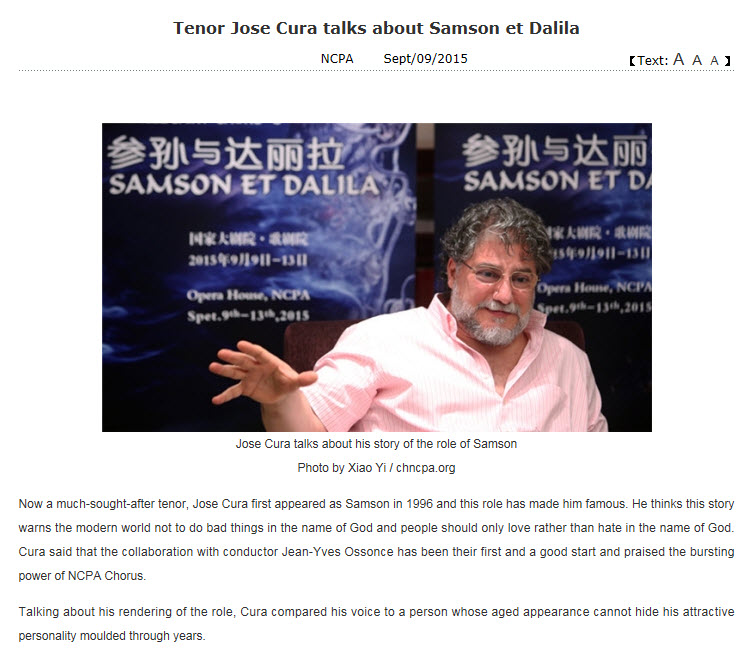

From September 9 through 13, the 52 year old Cura will appear in Beijing in a National Theater and Teatro Regio (Turin) co-production of the grand opera Samson et Dalila, in which he plays one of his best roles, Samson. This is not the first time this tenor who is in his prime has visited China. In early 2007 Cura starred in a modern version of Turandot, which became the year’s most popular classical music and cultural event.

Cura has the sturdy appearance of the mighty ancient warriors. “When I walk the streets of Beijing, there are always a lot of people looking at me, maybe because I am tall and strong, bearded, people think I am like a statue.” Even though he has gained weight, a beard and fluffy curls that are beginning to turn white, you can still see the tall, handsome appearance Cura presented when he first became popular in Europe. He has played the hero’s role in many operas, the most famous of which is Otello, a role he first played when he was only 34 years old, become the youngest tenor to do so thus far.

Cura’s majestic fullness of tone has made him the model of the dramatic tenor, performing in many of Verdi’s and most of Puccini’s tenor roles. Similarly, he loves Samson et Dalila, the opera by the French composer Saint-Saëns. Since his debut in Samson et Dalila in London in 1996, he has sung in many productions; his (role) premiere Beijing is also the premiere of the opera in China.

“Twenty years ago, my body was stronger,” Cura said with a laugh, speaking of how age has changed his understanding of the role: as a young man he could be bare-chested and offer a strong, muscular interpretation of the ancient hero. Now, he finds the character’s spiritual dimensions to interpret this significant tragedy.

“Samson may have been history’s first suicide terrorist”

“My favorite opera roles are those that have credible plots that are close to reality.” Years ago, Cura insisted that the performance of a singer should be real, credibility, persuasive. To better interpret the role of the hero, Cura, who adheres to year-round physical training, was not only a fitness enthusiast but also a martial arts black belt.

Saint-Saëns took seven years to write Samson et Dalila, which remains the composer’s best known opera. The action takes place in 1150 BC and is based on the Biblical story of love and betrayal found in the Old Testament, a book with household recognition in Europe.

[…]

Samson is a Jewish warrior in Israel, a hero lost to love. The beautiful Dalila uses that love to learn the secret of his power and then betray him. Once Samson loses that power, the pagans blind him and turn him into a slave. “Samson may be the first suicide terrorist in history.” Cura said he understood the image of Samson as half-human, half-god, but that he forgot his invincible power came from God. “Arrogance made him lose contact with God, but he also lost his power.”

In the third act, with white cloth covering his eyes, Cura shoulders the burden of torture with trembling, painful singing, using meticulous care in shaping the image of a lonely hero in a hopeless situation. Saint-Saëns wrote against this scene a cheerful celebration of pagan dances, contrasting the failure of Samson. As the story moves toward the climax, Samson prays to God to restore his power and he is able to collapse the magnificent temple.

In the destruction at the end of the play, Cura sees the absurdity of the terrorist retaliation in the world. “The temple is filled with innumerable old people, men, women and children. Samson asks God for the divine power to destroy it all. He did not learn any lesson and is just like the pagans, not understanding that committing to revenge is a mistake. This is opera that maps to the modern age, when today’s terrorists do evil in the name of God, and sticks very close to real life.”

Opera fans like Samson et Dalila because Saint-Saëns wrote such moving music, from Dalila’s aria, Samson’s solo, the quartet, chorus and ballet scenes interspersed to capture both sight and sounds in a very rich opera.

Classical music’s versatile king

Cura has spent more than half his life on stage and more than 23 as a leading opera tenor, “but what I really like is conducting and directing.”

There is no one in classical music with Cura’s wide-ranging interests. He is not only an opera stage star but a conductor, composer, opera director, stage and costume designer and even a photographer with a published book.

He is also the first to have the ability to hold ‘half and half’ concert, where he sings a concert with a conductor in the first half and in the second half he conducts the symphony orchestra himself. In 2010, he performed in Samson et Dalila while directing and designing it. In 2012, he directed Puccini’s La rondine while also holding the jobs of set and costume designer.

In fact, in Cura’s boyhood he had only two dreams: to become a conductor or a professional football player. As early as age 15, Cura was a choral conductor. In 1988, while he was studying conducting and composing, he took a mandatory vocal course. In discovering his talent, and realizing there were no professional opportunities for young conductors in Argentina, the young tenor moved to Italy in 1991.

“If you want to become a singer of Italian opera, you have to go to Italy. Otherwise, you can never really understand Verdi and Puccini.” Cura said conducting is definitely what he loves most deeply, but he never thought his fame would rest on being a tenor.

In 1997, Cura won Operalia, the Plácido Domingo vocal competition, and opened with a series of highly successful debuts. In 1996, he was hailed as the most promising contemporary tenor. At age 34, he made a bold decision, to play Otello on stage in Turn at Teatro Regio; it was broadcast live across Italy. The youngest ever to perform Otello, he became the leader of the new generation of tenors.

“When I sing onstage, my mind is thinking of directing,” Cura said. He is currently the Prague Symphony Orchestra’s Artist in Residence with three performances a year while directing four or five operas. “Ten years ago I started directing, choreography, and costume design.”

“Life is too short. Dealing with superficial things is a kind of waste. I want to master as much knowledge and skills as possible in a limited life.” People always ask Cura how he has the energy to do the seemingly impossible. He stresses that what he does is complementary, rather than playing football today and cooking tomorrow. “I firmly believe that everyone can do more things than they are currently doing. A lot of people don’t because they are afraid of being blamed. The problem is not that I do too much but that too many people don’t do enough.”

Cura hopes that the next time he comes to China, it will be as an opera director. His participation in the opera Samson et Dalila has given him the sense that Chinese opera contains real strength. “I feel like Chinese Opera has a strong power that is about to erupt, but like a sleeping volcano is saving its energy.”

Samson et Dalila will be performed at the National Grand Theater

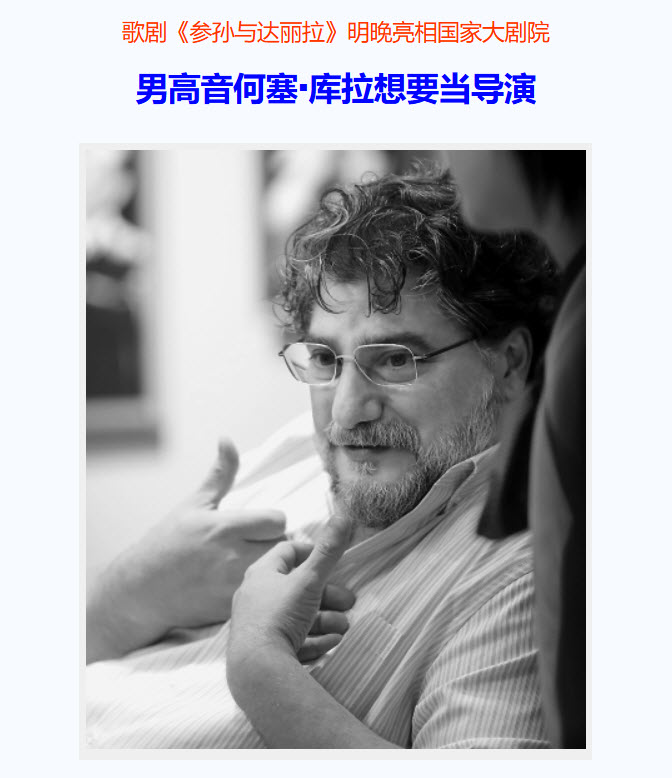

Tenor José Cura wants to be a director

BJD

Han Xuan

08 September 2015

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpt]

"A conductor who doesn't want to be a director won't be a good singer." In this era when everything is about crossover, this is the absolutely right sentence to describe the world-renowned tenor José Cura. Yesterday, Cura, who will play Samson in the opera Samson et Dalila, a co-production of the NCPA and the Royal Opera House of Turin, shared with the media his feelings about his upcoming debut on the Beijing stage. As a singer, Cura has yet to take the stage but with his interest in crossover, he is already thinking of coming as a director next time.

The appearance of Cura, a tall, strong, bearded “muscle man,” immediately reminds people of Samson, the strongman of Samson et Dalila, a role he has successfully played many times since 1996. The opera tells the story of the relationship between Samson and Dalila, a seductress who plots to destroy Samson by feigning love. How José Cura will fall under the heroine's spell is a matter of great anticipation but Cura isn’t revealing anything. "There will be a surprise for everyone. For now I will reveal just one thing - I will definitely not be naked."

But before Cura's debut in the house as a tenor is complete, he's already thinking about directing the next time he comes to Beijing. “The Samson I'm playing this time can only be described as director Hugo's version of the character. A lot of the interpretation of this Samson is in accordance with the director's intention, which can't exactly be described as José Cura’s version of Samson.” Cura said, “Maybe in the future I will return as a director myself with my own version of Samson.”

In fact, the world-renowned José Cura is not only an accomplished opera star but also a composer, conductor, opera director and stage designer. As a young man, Cura studied composition and orchestra conducting in his hometown. In the 1980s, Cura rose to fame with his distinctive voice but in 1999 he took up the baton again, collaborating with many world-class orchestras such as the London Philharmonic Orchestra and the London Symphony Orchestra to perform operas and symphonic works before joining the director circle. Whether in the orchestra pit, on the stage or behind the scenes, his performance has excited the audience.

Tomorrow night, the man who already has several identities will make his debut as a vocalist at the Grand Theater. Given that this is his debut in Beijing, he is full of anticipation. “What I'm most curious about is what young people think.” Cura said. “I was surprised when I arrived in China. In many foreign countries, most people who attend opera are in their 60s, but in China, most of the opera goers are young people. I'm looking forward to their reactions.”

Note: This is a computer-based translation. It is provided as a way to offer a general idea of the commentary but should not be considered definitive

José Cura Arrives

StarDaily

08 September 2015

[Excerpt]

José Cura arrived in Beijing yesterday and tomorrow will star in the National Theater’s debut of Samson; next time, he wants to be the director.

Final rehearsals of Samson et Dalila at the National Theater, the co-production with Teatro Region in Turin, are in full swing, with performances scheduled from September 9 through 12; however, José Cura, the male lead playing the Herculean Samson, arrived only yesterday. The performance is the first one in Beijing for this bearded artist, but Cura expressed the hope that the next time he came, it would not be as a singer but in the capacity of director.

José Cura has the reputation of “the brightest star in the tenor sky” and “super tenor.” In this production of Samson et Dalila, he is working with French conductor Jean-Yves Ossonce and director Hugo de Ana. In speaking of de Ana, Cura said he and the director had been good friends for twenty years, so much so that “in such a big production not everyone agrees but we are professional actors and the cooperation with the production team is very good. The young staff at the National Theater is also very happy to cooperate.”

Cura said he has many careers, as an opera singer, a director and conductor. “The change in my role is not a change in identity, but a complement to each other, so that my career has become more complete. But what I like most is not opera singing but directing and conducting.” Cura said the National Theater and the Theater Choir have great potential. “I very much hope that the next time I come to Beijing, it will be in the capacity as director so I can work with them. When I was among them, I felt a very strong force about to burst out, and I think they are like a volcano about to erupt with energy.”

Cura said he had acted in a lot of versions of Samson but that the most impressive was his filmed version of his own production. He said, “The role of Samson is very complex. From the story of Samson we should learn something, some sentiment, that in the name of God we can have love and kindness.”

Cura has had a very a very good impression of Beijing on his first visit. “I think the people are very friendly when I was window shopping. As I was walking, I think everyone was looking at me, because I am tall and strong but also because I have a beard, just like a statue but also a little bit of a stomach like a statue. I would very much like to give the Beijing audience a pleasant surprise.”

(Above photo was from interview with ChinaNews

Note: This is a computer-based translation that includes comments from José Cura. Cura uses words with precisions and imagery to effect. The computer does neither. Consider this to be an approximation only.

Interview with Tenor José Cura: My Favorite Thing is not Singing, but Conducting and Directing

BundPic

Lu Yi

September 2015

[Excerpts]

“I absolutely prefer conducting. When I studied music as a child, my dream was to become a conductor or composer. I studied vocal music only a part of the required courses. In South America forty years ago, a young conductor had a difficult time launching a career. I never thought I would become famous as a tenor. Of course, for young people to embark on the road of conducting is still not easy. This is a very difficult time.”

In every new city, José Cura likes to window shop; this is his way of seeing the world. “The Beijing residents I met in the streets were very friendly. They would stare at me, probably because I am tall and strong, with a beard, a big belly, just like a large sculpture.”

As a young man, Cura had dark brown, curly hair and a typically South American-style rugged, handsome face. His figure was tall and sturdy, much like a Greek sculpture. In 1996, as the era’s most promising 34-year old tenor, Cura starred in the live, televised production of Verdi’s opera Otello: no one before him had dared to play the complex, tragic commander Otello at such a young age.

In the 1970s, Pavarotti, Domingo and Carreras formed the “Three Tenors” and were gloriously triumphant. With the death of Luciano Pavarotti, Plácido Domingo turning baritone, and José Carreras no longer appearing in operas, people began looking for a successor to fill the vacancy of world’s top tenor. In the early 1990s, after the British media praised Cura as “the brightest star in the tenor sky,” people began referring to his as the “the world’s fourth tenor.”

From 9 through 13 September, Cura will appear for the first time on the Beijing opera stage, at the National Theater in a co-production with the Teatro Regio, Turin, of the ‘grand opera’ Samson et Dalila, in which he plays one of his best roles, Samson. Coincidentally, just two weeks ago the 74-year-old baritone Domingo performed in Simon Boccanegra on this same stage in what seems to be a heritage connection: Cura won Domingo’s vocal competition in 1994 at the start of his career.

“In the 21 years (since I won), Domingo and I have only worked together four or five times. Sometimes he served as a conductor, sometimes we participated in a concert together,” Cura said, adding that there has been no mentoring relationship between the two of them, in spite of what some people think, but rather opportunities to collaborate.

This is the first staging of Samson et Dalila in China and with one of the most prestigious tenor’s starring, it has become a popular topic of discussion in the capitol. As in 2007, when Cura starred in the modern version of Turandot in Shanghai, which fans still talked about as the event of the year.

The Accidental Tenor

For Cura, the road to becoming a world famous tenor was, in fact, full of coincidences.

Born in 1962 in Rosario, Argentina, Cura grew up among the neoclassical buildings of an industrial port city. His exposure to music was not early—he began to learn to play the guitar at age 12—but with his gift he became a choir conductor at age 15.

He had two boyhood dreams: one as a conductor, the other as a football [rugby] player. Eventually he found fame as a singer, but becoming a tenor was a fluke.

“My interest in opera came very slowly and started when I began to learn vocal music as a 21 year old,” Cura recalled, his initial interest in singing being only as it related to conducting and composing. Worse, he was unable to find the correct training method and almost ruined his voice. “I tried to find a better way but to no avail, so I gave up.”

He firmly believed it was his calling to become a conductor—until he had a chance to sing at a concert and people told him he was vocally talented and should continue to sing. When he was 26, he again began to learn vocal music and, slowly, to like opera.

“Life is always pushing you forward.” Cura has thanked his first teacher, Horacio Amauri, who taught Cura the basic skills. In 1991, when he went to Italy and worked with Vittorio Terranova to study Italian opera, he fully entered the door of opera.

Cura said that if you mention his name in music circles some people will mention his winning Domingo’s Operalia (as the start of his international career). In fact, of all the people who emerge as winners from this contest, not everyone goes on to success. Former champions disappear.

Cura had been focused on becoming “a good singer” and thought the competition was just a man-made, gorgeous fireworks. “I waited for the light to disappear, for everything to calm down. If people recognized you afterwards, it just proves you are an important and respected artist.”

Seeking Modern Meaning in Opera

In the 1990s, Cura made a series of highly successful debuts. In 1996, he premiered in London in his first Samson et Dalila to critical acclaim, and then in San Francisco he sang Bellini’s Norma and in Los Angeles he sang Bizet’s Carmen. The following year he worked with Sarah Brightman to create the classic album “Time to Say Goodbye,” consolidating his reputation in diverse areas.

To date, Cura has performed the tenor role in almost all of Puccini’s opera and many of Verdi’s. His favorite composer is Verdi; on the centenary of the composer, he released his own Verdi album (Verdi Arias) which features him singing and conducting. However, unlike predecessor tenors, Cura respects the authenticity of the theatrical performance.

“No one tenor can fully cope with all the tenor roles from Verdi’s pen. Similarly, you cannot expect all of Verdi’s arias to just happen to fit a single voice.” Cura has never been one to sing to the musical score; he is always trying to find ways to shape the role and the interpretation to fit the spirit of the character.

He has never thought that opera is a legacy of a bygone era. On the contrary, opera must be brought closer to present time, the leads must fold psychological and social analysis into the role development and create a dramatic line which modern audiences will appreciate.

“I started to sing Samson et Dalila in February 1996 and in the twenty years since I have sung countless versions.” Cura said that in those twenty years his understanding of Samson has not change. “Samson is probably history’s first suicide terrorist.”

Saint-Saëns took seven years to write Samson et Dalia. It takes place in 1150 BC and is the story of love and betrayal, based on the story in the Book of Judges from the Old Testament. The Israeli warrior Samson is bewitched by Dalila who uses her beauty to seduce him and betray his secrets; he is then blinded and put into slavery.

“Dalila is a tool by which God tested Samson 3500 years ago. It is a Bible story to educate young people to not be distracted by beauty.” Cura said that to win over a modern audience, you cannot continue to use the same thinking as in the past.

In 2010, he served as director, stage and costume designer and star in his own production of Samson et Dalila. “When the semi-divine Samson, who is lost in love, begins to grow arrogant, he loses touch with God and also loses his power. In the third act, he prays to God to return his powers but he has not learned his lesson and in hatred commits suicide, killing everyone, making the same mistake as the pagans. In classical literature theory, Samson is a negative hero. Today’s heroes, in the name of God, with hatred commit suicide and destroy the world, this is the reality of actual conflicts.”

“We must search for the meaning of opera in the modern sense and should not ignore the story of modernity. This is the future of opera,” Cura said.

Conducting will be my way forward

Despite his exalted status in the opera world, Cura is not satisfied just being a tenor. He never wanted to be a piece in a commercial board game, but to be an artist. In 2000, because he was dissatisfied with how his production team was commercializing him, he ended negotiations and left. “I had studied music for more than twenty years, not to be just a product. I needed art and respect.”

In Cura’s experience, a conductor can become a tenor, even if a low probability event, but he can also continue to develop in the field, learning choreography and costume design, every detail of the entire opera production. He knows that by merging his talents he can control the general situation and the minor details of the opera entirely. He believes that the more experience and skills a musician has, the richer the content on the stage.

When Cura is asked he manages to do all this, he shrugged. “My life is work, study, research. While others are resting, I’m working. When others are sleeping, I’m learning. When others are on vacation, I am at home preparing for a new opera production.”

Right now, Cura is singing on an opera stage about 50 days a year and he hopes to maintain his voice from a physical point of view.

He is not afraid to retire. “The day I decide to step down from the stage as a tenor, conducting is the other way I will go.”

(article from above continues with Q&A session)

Q&A

Q: At the age of 15 you were a choral conductor and held your first public performance. You were just a high school student. How did you manage it?

JC: At the time I was a junior high school student. Why is it impossible to be a conductor at fifteen? The people in the orchestra are older compared to you but if you wait until you are that much older, it will certainly be too late.

Did I sleep for ten hours every days, then go to school, to dances, listen to rock and roll when I was thirteen? No. I remember getting up at 5 AM every day to study music and go to school at 8:30. If you want to do something, anything is possible. Of course, I was not the best young conductor at that age, just a child who is learning how to conduct.”

Q: In1991 you moved from Italy from Argentina to begin true professional vocal training. What made you decide to turn to vocal music?

JC: When I went to Italy it was as a professional singer but not one with a lot of lessons. When I studied vocal music while attending university it was because to conduct I had to complete many different disciplines, including composition, flute and drum. I was singing in the opera chorus because of the obligation to learn vocal music. One teacher said I sounded good and I started to study vocal music in earnest.

If you want to become a good Italian opera singer, you have to go to Italy; otherwise you cannot really understand Italian opera. ….

Q: How many opera roles have you starred in?

JC: I don’t know. So far, in my theatrical career I have performed over 2200 times, so perhaps thirty or forty roles.

Q: You were the first to use the “half and half” concert, where you both sing and conduct. Which capacity do you prefer?

JC: I’m not sure I’m the only one but I’m sure a lot of people can do it since, technically speaking, it is not difficult.

I definitely prefer conducting. As I child studying music, it was my dream to become a conductor or a composer. Learning vocal music was just part of the required coursework. In South America forty years ago, a young conductor had a difficult time in launching a career. I never thought I would become famous as a tenor. Of course, for young people to embark on the road of conducting is still not easy. This is a very difficult time.”

Q: In 2010 you created the production of the opera Samson et Dalila as director, stage and costume designer, and singer. In 2012 you put Puccini’s La rondine on the stage as conductor, director, stage and costume designer. This transformation sounds incredible.

JC: Every change of identity was not a change but rather a complement to the others, so that the music became more complete. If I were a football player today and a chief tomorrow, that is called transformation. My favorite thing is not singing but conducting and directing. I favor teamwork, leading a team rather than acting independently.

Q: You hold so many roles in a production—is it because you think other people are not doing it well enough?

JC: It is not that I’m not satisfied; it’s just that I want to do these things. I firmly believe that everyone can do more than they currently do. A lot of people don't do more either because they are afraid of the responsibility or because they lack energy.

If you do a lot of work it means sacrifice. There are always people asking me how I do so many things. I ask you, if you were in my position and you had the opportunity to do so many things, what would you do? Michelangelo is the best architect, the best artist, the best sculptor, but also a poet. Everything is possible. To do these things, he worked hard.

The issue is not that I do too much, but that a lot of people do nothing. This is a common problem in our world. People would rather play on their phone, no longer thinking, no one depending on their brains.

Q: You said on Facebook that you were worried about mass media and the progress of science and technology will have an adverse effect on the younger generation.

JC: I am not against scientific and technological progress. I also use IPhone 6. The phone is not the problem. The problem comes when you allow the machines to think instead of you. Young people cannot image a world without the Internet. The progress of science and technology has made life easier. But if we stop using muscles, over time the muscles will become laze and lose capacity. The mind is the same. I know I sound like an old man….

Q: You said opera singers should not just play the role but be authentic. To play the role of the hero, you worked out and got a black belt in karate. I have even heard that you are an electrician and you repair the house you live in?

JC: My house is a big house. It was not possible for me to build it but if you have the opportunity to go into my house, you will find many things made by my own hand.

I played baseball as a child and wanted to be a rugby player. I love fitness, studied Chinese Kung Fu and karate, but that was 25 years ago, before I gained 25 kilos.

Q: How do you have the stamina to master so many skills?

JC: Life is too short, without enough time to be bored so to use that time for superficial matters is a waste. When you are a young man looking at this life, it is life coming to you, you still have that whole life. But in middle age, when you look at your life, time is running at a very fast pace. When you are young you feel that life is slow but in middle age you feel time is flying by.

To learn as much as possible is that short life you must study. I couldn’t live a life that was spent watching TV at home. I hope, in my limited life, to make life richer. I hope that one day I do not look back only to discover I have not done anything.

Q. Your favorite singer is Karen Carpenter. You have said you loved listening to jazz and symphonies but not to opera.

JC: Karen Carpenter is my favorite singer. I’m not talking about her music but about her voice. She had a special tone and timbre that was especially warm and pure.

I never listen to opera in my spare time, absolutely not. Of course, it is not because I don’t like it, but because it is my job. When you spend eight hours of your day with opera, when you go home you have to put aside opera. In fact, I do not listen to much music when I rest. I prefer silence.

Q: In the last 30 years you have been keen on photography. Is photography another way that allows you to observe the world?

JC: Photography can bring me peace. It's my hobby, part of my passion, but also a way of looking at life. I’ve been improving and practicing my photography and have talked with many outstanding photographers. My photography is just for myself. I want to know the human heart through people’s faces. I want to reveal their souls.

Q: In 2008 you published a book of photographs. In what style?

JC: If you want to know, go buy it! (laughs). It is a collection of black and white photographs. I like to take photos of ordinary people but I don't think people need my photos. They aren't necessary. I never wanted to publish a book of pictures but in 2008 a Swiss publisher came to me and said, I have seen some of you pictures. I want to publish a book. He convinced me, “You can’t become a Richard Avedon but you are a well-known artist, people will want to see how you see the world. It will be a good thing.”

Q: When you appear on an opera stage, you always erupt with huge energy, volume and penetrating power. How do you do it?

JC: Today I am almost thirty years into a singing career. I cannot say that I have a young, pure, powerful, fresh, beautiful voice. Now when you come to the theater to hear me sing, what you hear will certainly not perfect but you can hear my energy, my strength, my charisma. Those are the elements included in my performances. These are the most important things an artist brings to the stage and they become more important as time passes.

Q: Looking back on those thirty years, what time made you feel the most honored?

JC: None. My glory is in my family. I was fifteen when I met my wife. We have three children. That is my greatest honor.

Note: This is a computer-based translation that includes comments from José Cura. Cura uses words with precisions and imagery to effect. The computer does neither. Consider this to be an approximation only.

José Cura is no ‘Law-abiding’ Tenor

Beijing Morning News

Li Cheng

September 2015

[Excerpts]

The star of Samson et Dalila hopes to return next time as an opera director

“If you ask me whether it is singing, conducting composing, directing choreography, costume designing I like best, it would be directing because I like working as a team. Working alone does not maximize results. I hope to collaborate with the National Theater next time as an opera director.” The world-renown tenor who is famous for his role as Samson, just two days away from his debut in Samson et Dalila at the National Theater, has not yet settled in but is smart enough to use the capital media to sell theater director Cura and his opera productions.

Yesterday evening Cura faced Beijing’s media in a press conference, making no secret that he does not entirely agree with director Hugo de Ana--his fellow countryman and friend for more than twenty years—version of the opera. “You will see that I act the Samson that is in Director Hugo’s mind, which is not exactly my idea of Samson.”

Cura immediately began to sell his own production version. “If you go to Amazon and search for Samson et Dalila with José Cura’s name, that is my performance of Samson, where I sang, directed, designed the stage art and the costumes. That, in my mind, is Samson!” As to this Samson, he keeps us guessing. “This is the first time I sing opera in Beijing. The shape of my Samson will give the audience a surprise. But of course, it will only be revealed on 9 September!”

Beijing Morning News had an exclusive interview with the legendary restless tenor on the same day he arrived in Beijing. Having performed in Samson et Dalila for twenty years, Cura has a profound understanding of Samson: “Samson is a negative hero.”

Q: What year did you first sing Samson? How many versions of it have you sung? How many times?

JC: I first sang Samson twenty years ago, in February 1996. As to the number of different productions and number of performances, I can’t remember them all--there are too many! In 2010 I created a very beautiful version of Samson et Dalila. You can find it on Amazon as a DVD edition.

Q: In the twenty years that you have been singing Samson, has your understanding of the role changed?

JC: In twenty years my views on the role have not changed much, but twenty years ago, I relied more on a physical performance, being stronger. Even now I maintain a strong sense of the physical body but there is a stronger spiritual sense that was not available twenty years ago.

Q: How do you understand the character of Samson?

JC: I think he might have been history’s first suicide-type terrorist. In the final scene, in the temple, there are so many men and women and when he appealed to God to restore his power, he destroyed the temple. So many people were crushed to death inside it with him. The story has a profound modern meaning, in which we invoke the name of God to do bad things, historically and everywhere today. The opera tells us that in the name of the Lord, there can be only love and never hate. So, in my understanding, Samson is a negative hero.

Q: What kind of role is Dalila?

JC: God uses Dalila to test Samson, so it doesn’t matter if she is Dalila or someone else. Over 3500 years ago, to teach young people not to be so attracted to beauty, such a story might be more persuasive. At that time, people believed that being sexually attractive was a great sin.

Q: How do you manage to have such a dramatic voice?

JC: I think voices should be understood as an integration of sounds and that voices contain a variety of information. Sound is a material. When a person uses it a certain way it can convey different feelings to another. I have experienced an almost 30-year long career so I can no longer talk about a young, fresh, powerful voice, but when I am on stage, the energy and charm fuse in my voice and my performance. This I think is the most important thing as an artist. I would also like to ask you a question. Did you think Brad Pitt was handsome when he was young? And now is the nearly 50-year-old Brad Pitt still handsome?

Q: Of course. Now that he is older he has more character!

JC: In my view, after time settles things, the art is the most important.

Q: When did you begin to realize you could conduct?

JC: It was just the opposite. I was 15 years old when I began to study composition and conducting and 29 years old when I began to sing. But I became famous as a tenor, so today this interview is with tenor José Cura.

Q: So when did you come to understand that you would sing opera rather than conduct?

JC: When I was in college at 21 years of age, my major was conducting. I needed to learn a variety of musical instruments and of course to learn vocal music. I had never tried the opera repertoire but one teacher said to me: your voice is very good. You must sing. So after I finished composition and conducting courses, I began studying voice seriously.

Q: When did you realize that you had so many various talents?

JC: About ten years ago I discovered I had a talent in terms of design. In addition, I also like photography. In 2008 I also published a photography book. Life is too short, without enough time to be bored!

Q: If the National Theater invites you to return as a director, which opera would you chose?

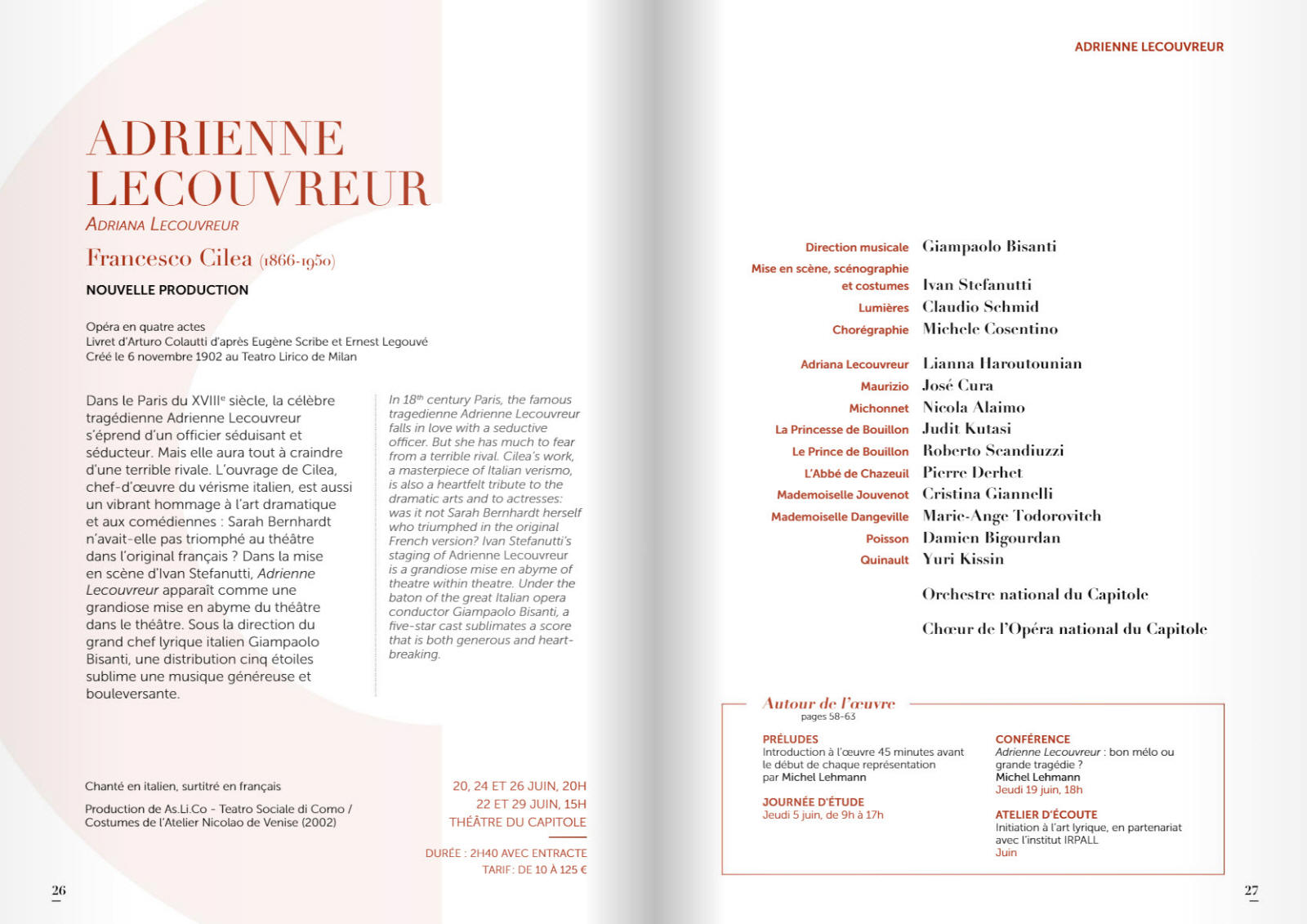

JC: My first choice would be Britten’s Peter Grimes. This is a major drama, very suitable for a big theater stage. In 2017 I will product this opera in Germany. In addition to singing, I will be doing the directing, stage and costume designs and the choreography.

I always have people asking me how I do so many things. I would say the question isn’t why I do so much but why they do so little. This is a universal issue in the world today.

Note: This is a computer-based translation that includes comments from José Cura. Cura uses words with precisions and imagery to effect. The computer does neither. Consider this to be an approximation only.

Samson et Dalila: José Cura Interprets a Anti-Hero

Sina Weibo

8 September 2015

[Excerpt]

José Cura: Energy and the power of charisma are included in my vocal performances.

Samson et Dalila is one of José Cura’s best operas. As a world-famous tenor, Cura has sung the role for twenty years, he said during an interview with the Sina Weibo reporter. “Twenty years ago, in February 1996, I sang the role for the first time. In 2010, in Germany I directed a very beautiful version of Samson et Dalila and filmed it.”

In performances of Samson et Dalila José Cura’s singing is stunning, with great power and a unique temperament that is widely praised. When it comes to his voice, Cura said, “When I perform in an opera, I always feel that my voice is the fusion of various information. Sound (voice) is a material, a raw material that can be used by one person but is not the same in another. We can have an experience of seeing a man or a woman whom we feel is perfect but who doesn’t convey any information to us. Sometimes they aren’t so perfect on the surface but the personality and personal characteristics impact us deeply so you think this person is beautiful. The same is true of the voice. Even if the voice is perfect, if the person using the voice does not have good character traits and charisma, then there is no significance. If you are an expert who is coming to the theater to listen to me, my singing will not be perfect, but you can still hear the energy, the power, the charm that are included in my vocal performance. That to me is the most important point as an artist.”

José Cura begat to study conducting and composition at the age of 15 and began formal vocal training at the age of 29. “Conducting influences my singing very much. When I sing there is wisdom in my head about how to sing. Yesterday I was in rehearsals with an opera conductor I didn’t know, who had been rehearsing with the chorus that afternoon. The conductor said, ‘I rehearse with you easily, as if we had been in rehearsal for two weeks.’ I know what the conductor needs and help him do it. I conduct a lot. I’ve conducted thirty-four operas. I am serving as the resident conductor at the Prague Symphony Orchestra. I believe that everyone can do more things than they do, that many people do not because they are afraid of what other people say or because they do not have the energy or to do a lot of work would require sacrifice. Someone asked me how I can do so many things. In turn I ask him, if you were in my position and could do such a thing, would you do it or not? The problem is not that I do too much, the problem is that you do too little.”

|

|

|

|

||||

.jpg) |

|

Samson et Dalila with José Cura

José Cura's performance is eye-catching

Beijing Times

14 September 2015

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpt]

In addition to writing famous instrumental works such as Carnival of the Animals and Introduction and Rondo Capriccio, French composer Saint-Saëns also created 13 operas. Among them, Samson et Dalila is the only one now performed as a repertoire by major opera houses around the world.

Especially in the third act, when Samson sang the famous aria "I am sad and sorrowful" in prison, Cura's singing with a crying voice vividly portrayed Samson's miserable situation and sincere repentance in his heart. When Samson regained his divine power and sang the last high note at the moment of pushing down the stone pillar, a warrior finally gained spiritual rebirth.

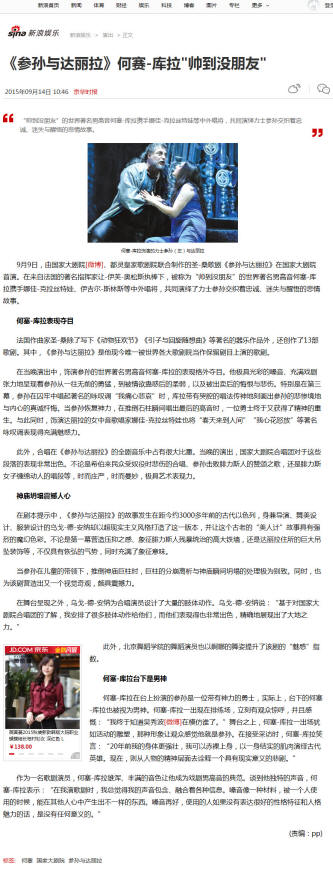

In the evening's performance, the world-renowned tenor José Cura who played Samson, gave an outstanding performance. His luminous voice, full of dramatic tension, portrayed Samson's courage, his weakness after being compelled by lust, and his regret and sadness after being betrayed. Especially in the third act, when Samson sings the famous aria Vois ma misère, hèlas in the prison, Cura’s voice was full of tears as he portrays Samson's tragic situation and sincere repentance. When Samson regained his strength and sang his final high note as he pushed down the stone pillar, the warrior gained spiritual rebirth.

The collapse of the temple is shocking

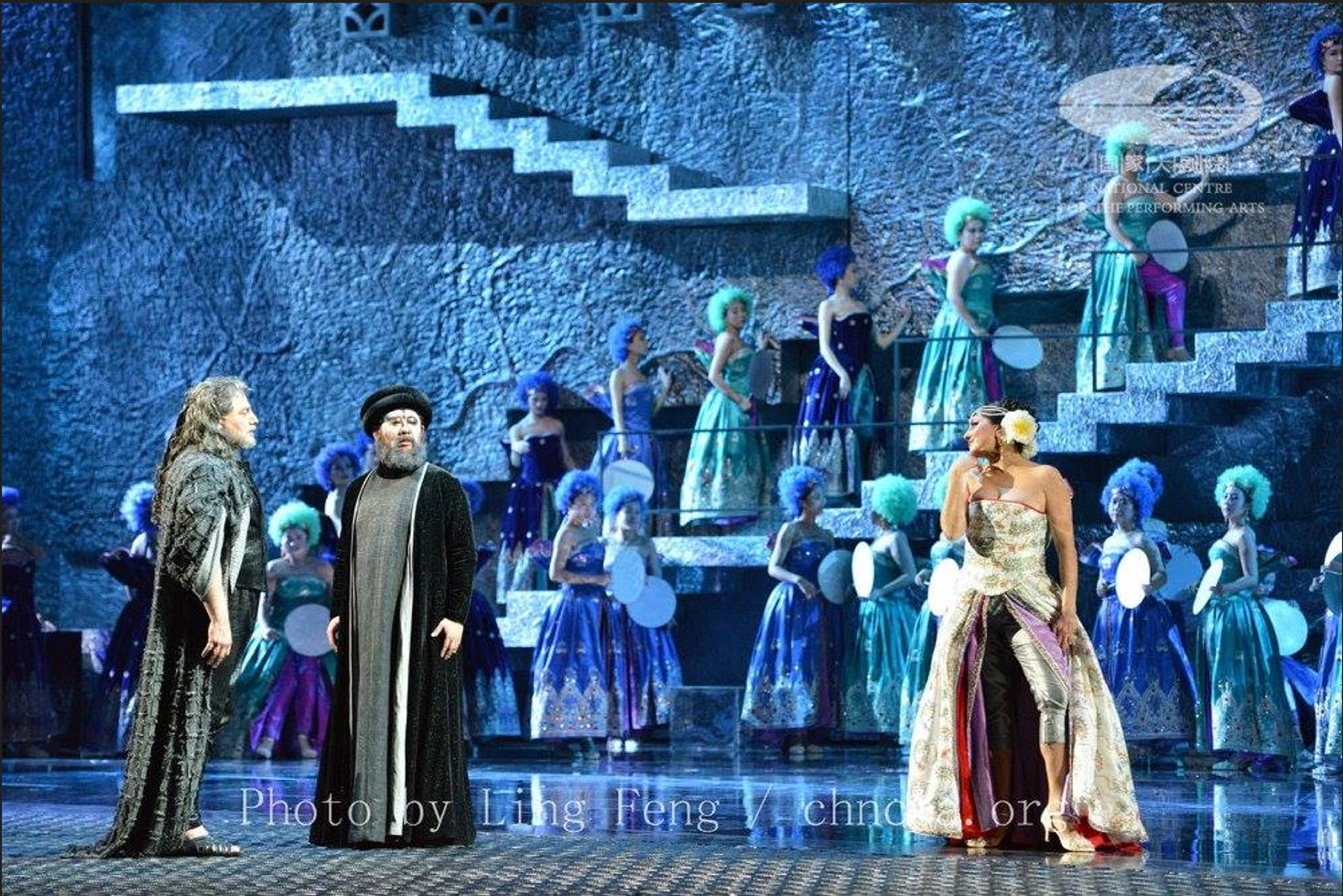

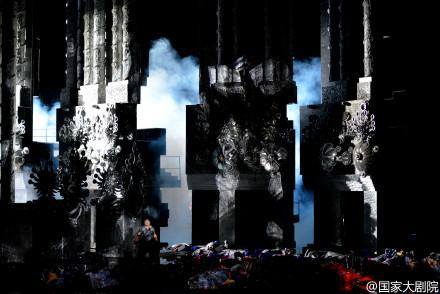

According to the story, Samson et Dalila takes place in ancient Israel about 3,000 years ago. Ugo de Ana, who is the director as well as the stage designer, and costume designer, created this version in a surrealist style and gave this ancient "honey trap" story a strong magical color. Whether it is the high iron wall in the first act that creates a sense of oppression and symbolizes the brutal rule of the Philistines, or the huge pendant decoration in Dalila's residence, the staging was full of symbolic meaning. The toppling of the pillars and the instant collapse of the temple were handled with great style that provided the final, shocking spectacle for the play.

[…]

The Samson played by Jose Cura is a warrior with divine power. On the stage, he appeared as a moving sculpture, an image that allowed the audience to more clearly identify as the Biblical hero. In an interview, Cura acknowledge his physical stature was a plus in the role. "Twenty years ago, my body was stronger. I could be shirtless and interpret ancient heroes displaying strong muscles. Now, it's about interpreting a realistic tragedy from the spiritual side of the character."

No matter how good the voice is, it is meaningless if the person using it does not express good personality traits and personal charm."

As an opera singer, José Cura's majestic, full-bodied tone makes him a model for dramatic tenors. Speaking of his unique voice, José said, "When I perform opera, I always feel that my voice contains and blends various messages. The voice is like a material that, when employed well, can produce something extraordinary in the hearts of others. No matter how great a voice is, it is meaningless if not used to express great character traits and personality."

Note: This is a machine-based translation. It is provided as a way to offer a general idea of the conversation and the ideas exchanged but should not be considered definitive

José Cura’s Voice Holds Sorrow

BJRB and BJ Xinhua

10 September 2015

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpt]

The opera Samson et Dalila premieres for the first time in China; the theatrical elements manufactures a “brightly blind…”

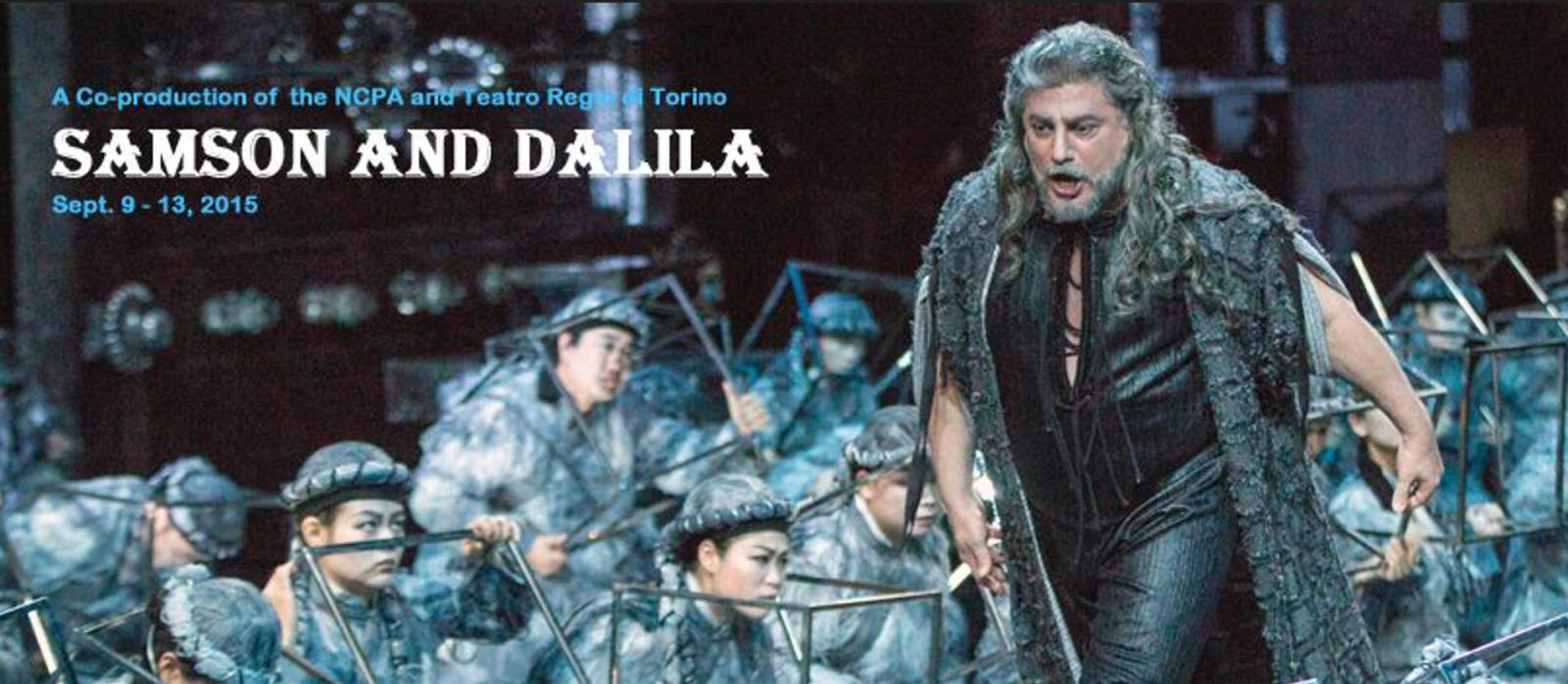

At the National Theater the curtain opens to dozens of stainless steel prop cubes neatly arranged in three rows on the stage. The music begins, a group of enslaved ‘Hebrews” is summoned by the sound, then world-famous tenor José Cura strides onto the stage. Yesterday, the National Theater, in a co-production with Teatro Regio in Turin, premiered the Saint-Saens opera Samson et Dalila, with José Cura’s compelling voice coupled with a metallic stage setting bringing the audience an intense experience.

The story of the ‘hero tempted by beauty’ is an opera that can be said to be something of a José Cura specialty. Having performed in several versions of Samson and Delilah over the past 20 years, Cura has lost count of the number of times he has performed this ancient Biblical story. This, however, was his first visit to Beijing as well as the first time this tragic hero has appeared on a Chinese stage. “When I walk the streets of Beijing, there are a lot of people who look at me, probably because I am tall and big but also because I have a full beard. People think I look like a statue,” Cura said in a previous interview, making fun of himself.

The statue-like fourth tenor of the world did not disappoint the audience. Last night, he presented the "three faces" of Samson with a voice full of dramatic tension. Whether presenting the sonorous voice of the warrior in the first act, the confused lustful tenderness in the second, or finally, in the third, the sound of the betrayed, remorseful and sorrowful, Cura’s voice was always full of character. This was especially noticeable in the third act when Samson, who has had had his eyes gouged out, sang the famous aria Vois ma misère, hèlas while in chains in prison. He vividly expressed Samson’s miserable situation with his evocative singing, presenting the abject hero with meticulous dramatic accuracy

However, the surrealism of director Hugo de Anna's production seemed to distract from the drama and José Cura's classic singing, and frequently stimulated the audience's eyes. From the stainless steel box in Act I that shows the labor of the Hebrew slaves, to the huge pendant hanging from the sky in Dahlia's bedroom in Act II, to the illuminated stick in the hands of the Philistines in Act III, all the props were set up in a way that was very much in line with the plot. Under the light, the reflective effect with metallic texture brought great visual stimulation to the audience, and many people called “blind”.

Regardless of the production of Samson et Dalila, the finale in which Samson pulls down the pillars is always the focus of attention for the audience. In previous versions, the pillars themselves almost always break. In this version, which Cura called “the revenge of the terrorist,” Samson is led by a child to the temple pillars and at that moment the theater lights go dark and in the flashing light a hole appears in the temple, then the pillars appear broken, the temple collapses, fissures explode with dazzling white light. The opera Samson et Dalila has ended but the audience has not yet recovered from the shock.

At the end of this run of performances in China, Samson et Dalila moves to Teatro Regio in Turin, Italy, a chance to show the quality of a Chinese Opera production.

Note: This is a machine-based translation. It is provided as a way to offer a general idea of the conversation and the ideas exchanged but should not be considered definitive

Samson and Dalila

BJWD

The National Theater, in a joint production with Turin’s Teatro Regio, made its premiere appearance last night. Under the baton of the famous French conductor Jean-Yves Ossonce, world famous tenor José Cura, singers Nadia Krasteva and Egils Silins and other foreign and Chinese performers together created an interpretation of Samson that intertwined faith (loyalty) and betrayal.

The work as performed revealed the grandness in French Grand Opera.

Samson and Dalila is a story selected from the Bible’s Book of Judges. Samson is a fierce Hebrew hero who falls under the charms of the beautiful Dalila, the woman who ultimately succeeds is obtaining his divine secret, and who is subsequently tortured in prison, repents and, after having his power restored, destroys the (Philistine’s) temple. In the premiere, José Cura was exceptionally impressive in the role of Samson, presenting a complete Samson from the sonorous brave warrior of unquestioned integrity through the man bewitched by (lusting after) flesh, finally transitioning to regret and sadness after being betrayed. Especially in the third act, when the imprisoned Samson sang the famous aria “Vois ma misère, hèlas,” Cura’s employed a tearful singing voice to offer a vivid portrait of a the misery in Samson’s heart and his sincere repentance.

The stage effects of Samson and Dalila were amazing. In the first act, the brutal rule of the Philistines is symbolized by the tall iron walls while the huge decorative pendants in Dalila’s huge bedroom put the audience in the historical context. Most amazing was the opera’s end, when Samson, who was led to the temple pillars by a child, pulled those pillars down. With projections and an ingenious set design, the temple collapsed on the stage to crush everyone to death in a very realistic, chilling effect.

The opera Samson and Dalila is also designed to incorporate a number of dance scenes, here gracefully presented by the Beijing Ballet Dance Academy to add color to the stage. The work also has a chorus of 79 and 45 actors so there many spectacular polyphonic ensembles, difficult to manage but the actors were methodical.

Note: This is a machine-based translation. It is provided as a way to offer a general idea of the conversation and the ideas exchanged but should not be considered definitive

Samson et Dalila: José Cura Interprets Samson with his Magnificent Voice

China Youth Daily / art.ifeng

2015-09-11

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpts]

On the international opera stage, it is often said that the dramatic tenor is the hero with the “Golden Trumpet.” In the opera Samson et Dalila, premiered at the National Grand Theater last night, the world famous tenor José Cura let the Beijing audience experience a truly dramatic tenor with that gold trumpet style: Cura plays Samson as a god and from the first scene his voice was powerful and magnificent, passing through the symphony orchestra and filling every corner of the opera house, allowing you to feel the power of Samson.

José Cura has been performing Samson for 20 years, and countless performances have enabled him to understand the character. He knows that not every line of his singing needs to be forceful; he allows his voice to become very gentle when seduced by Dalila. His voice is not the polished lyric tenors we are most used to but his formidable breath control allows Cura to capture the emotional elements in his singing and adapting those emotions as needed.

In the Act III prison scene, when he sang the aria “Vois ma misère, hèlas,” he played with the volume of his voice, shifting from weak to strong. When he sang softly, his voice conveyed full of emotions; when he sang forte, it rang out like a mighty bell. Such rich use of the voice deeply touched the hearts of the audience

What sort of French opera is Samson et Dalila? Is it magical or tragic? Director Hugo de Anna did not seem to find a clear line, focusing instead on the magic at the expense of the inner lives of the character and thus the opera seemed a bit messy in its overall conception. On stage he joined many Chinese elements, many of them fantasy, putting in the hands of the characters shiny sticks and using metal framework and having Samson in prison always carrying a bright silver stick, all increasing the magical aspect but weakening the character portrayal.

Used to seeing more realism, the Beijing opera audience seemed somewhat surprised by De Anna’s magical approach. After the performance, the audience was vocal. Of course, both supporters and opponents have their own opinions, but for an opera director it is crucial to explain the story to the Beijing audience instead of showing off magic techniques that take away from the plot. One audience member summed it up for all: "Thanks to José Cura's performance, it is worth watching this unfamiliar opera!"

|

|

|

|

Opera Fusion

BravoCura Review of Samson et Dalila, Beijing

The success of Samson et Dalila, starring José Cura at his best in this signature roles, was reflected in the overwhelming ovation

Incorporating local color seems to be something of a growing trend with opera directors: consider José Cura's highly successful infusion of Argentine sensibilities, including tango and bandoneon, into his Cavalleria rusticana and Pagliacci. Director Hugo de Ana attempted a similar approach in the Beijing production of Samson et Dalila by introducing traditional Chinese elements into the Biblical story. But while De Ana’s Samson ticked off all the boxes as far as structure and spectacle, it failed to produce the heat and heart this quintessential human drama demands. Compared with Cura’s efforts--Cura beautifully maintained the intense emotional balance between his cast, the storyline, the music and the audience throughout his integrated staging—de Ana’s success rested primarily on opulent sets, polished choreography and his star tenor.

This co-production with Teatro Regio combined modern multi-media and metal stage elements with more traditional Chinese theater practices. The painted and masked Asians and Dalila’s troupe with brightly colored wigs bordered on cartoonish but with a dollop of suspension of disbelief, the fusion of styles more or less worked. De Ana, also responsible for sets and costumes, filled the stage with increasingly lavish designs and used lighting (light boxes to illuminate the faces of the Hebrews in the Act I hymn of deliverance, light sticks for the extravaganza in Act III) to add emphasis. With an apparently unlimited number of cast members, he populated the stage with so many singers, dancers and supernumeraries that the human drama was lost. At other times, de Ana used decidedly static and choreographed moments that slowed the narrative: the stylized ‘battle’ between Samson and the Philistine warriors and the ‘dance’ of Dalila and her acolytes, with its poses and repetitive hand movements, made theatrical statements rather than emotional connections.

The director maintained loose historical ties with the Biblical story by modifying some of the religious aspects of the work: In Act I Samson does not defeat Abimelech in battle but rather by extending the hand of God to crush the enemy’s heart--a powerful and magical depiction of God’s ability but not a particularly intense one. In Act II, the voice of God heard and seen in the storm that rages as Samson struggles between Dalila and faith is significantly downplayed, lessening the dramatic impact. And in the Act III finale, Samson survives the destruction of the temple, standing tall and triumphant amidst the carnage.

That Samson survives is not an original concept; it was a feature of the Deutsche Oper’s controversial staging several years ago. While not a traditional reading, it was effective, perhaps particularly so in China where Cura's physical size and presence lends itself to mythology. The extended ending, which continued the destruction of the temple long after the pillars fell and the music ceased, made for a more satisfying conclusion than Saint-Saëns‘ abrupt stop and rapid curtain drop. It also provided a nice symmetry to the opening where the opera music was delayed to allow the arrival of the Hebrews. Whether these embellishments enhanced the work or undermined it is open to robust discussion.

Given the strength and weakness of de Ana’s production, José Cura's Samson was virtually flawless in both performance and vocals. He elected to engage during the more stylized moments and become the still, powerful center when the production became too busy--highly effective. His command of the role began with his stirring exhortation to the Israelis in Act I ("Arrêtez, ô mes frères"), continued through his tender response to Dalila’s "Mon cœur s'ouvre à ta voix" and his heartbreaking “Vois ma misère, hèlas,” and culminated in the glorious final moments. As an actor, he provided a master class, commanding as much attention when he lay prone in Act III as he did when he was standing on the platform in Act I. He mesmerized, earning a substantial and sustained ovation from the appreciative audience.

His charismatic presence was necessary, given Nadia Krasteva as his Dalila. Krasteva was vocally adequate but her stage mannerisms were off-putting; her body movements and facial features often lagged behind the vocal line. She turned one of the most seductive scenes in opera ("Mon cœur s'ouvre à ta voix") into caricature by ceaselessly tossing her hair, endlessly touching herself, constantly stretching, and bizarrely sticking her foot into Samson’s face as an erotic gesture, all while staring at the conductor and leaving her Samson without anyone with whom to interact. Her desperate overacting continued in the third act when she ping-ponged between glee at defeating her enemy and horror at what she had done; neither were convincing. This Dalila was better heard than seen.

All three performances had noticeable musical issues with the pit but the orchestra will improve with more experience. The conductor, Jean-Yves Ossonce, was adequate, no more, and the bacchanal--music that should get the heart racing and the passion rising--lacked any sense of fire and brimstone; it was tepid. Choreography was equally tame but the young dancers seemed well trained and ready for more dynamic, inventive moves—as with the orchestra, there seems to be great promise and underlying strength.

The somewhat Kabuki-like Asian aspects of this Samson was different but also allowed for an easy differentiation between the material, manipulative, and powerful Philistines and the simple, defensive, humane Hebrews. It will be interesting to see how well this production plays in Italy.

Samson et Dalila is a powerful opera full of memorable music and high drama but it can present staging problems. Notable recent productions include José Cura’s in Karlsruhe (available on DVD). The Beijing production failed to create the same emotional impact or the dramatic tension of the Karlsruhe staging but the fault lies less with the fusion of East and West than with other directorial decisions and an unwieldy Dalila. Still, de Ana’s approach worked well in Beijing, where the audience seemed deliriously happy at the end of the evening.

And significantly, the willingness of the NCPA to offer great operas and its commitment to educating the populace will provide exciting opportunities for western directors and performers.

Note: This is a machine-based translation. It is provided as a way to offer a general idea of the commentary but should not be considered definitive

French “Grand Opera”: Samson et Dalila Grand Premiere

China News

September 2015

[Excerpts]

The French Grand Opera, Samson et Dalila, a co-production of the National Theater and Teatro Regio in Turin, premiered 9 September 2015 under the baton of the famous French conductor Jean-Yves Ossonce, world famous tenor José Cura, singers Nadia Krasteva and and other foreign and Chinese performers who together created an interpretation of Samson that intertwined faith and betrayal. At the same time, well-known opera director Hugo de Ana’s surreal fantasy-style choreography and ambitious staging of the production showcased the grand in French Grand Opera.

The French composer Saint-Saëns wrote many well-known instrumental works like Carnival of the Animals and Introduction et Rondo Capriccioso but also created 13 operas. Among them, his Biblical story of Samson et Dalila is the only one still in the repertoire of opera houses around the world.

It the evening’s performance, the world famous tenor José Cura, who played Samson, was particularly noteworthy. His was a great and glorious voice, full of dramatic tension, resonant as a warrior, tender and confused when bewitched, remorseful and sorrowful after betrayal. Especially in the third act, when Samson sang the famous prison aria “Vois ma misère, hèlas,” Cura’s singing vividly depicted his misery, confession, and sincere repentance. When Samson regained his power and suddenly pulled down the pillars, his penetrating voice was powerful, impressive. Mezzo-soprano Nadia Krasteva, who played Dalila, performed "Printemps qui commence" and "Mon cœur s'ouvre à ta voix" and other famous arias with forced charm. The Beijing audience’s enthusiasm infected José Cura, who said, “I hope that in the future that I come not only as a singer to the National Theater but as a conductor and director …”

In addition, the chorus in Samson et Dalila accounts for a large portion of the total music sung. In last evening’s performance, the National Theater Chorus did a great job in these moments. Regardless of whether they were the Hebrew people enslaved in a chorus of grief or praising Samson after the defeat of the Philistines, they were sometimes solemn, sometimes graceful, always expressive.

The story of Samson et Dalila takes place some 3,000 years ago in Biblical times. Director, set designer and costumer Hugo de Ana used a surrealistic style to create his version of Samson et Dalila and made this ‘honey trap’ story that happened in a distant era strongly magical. Whether in the first act he used tall iron walls as symbols of the repression and brutality of the Philistines or the giant pendants decorating Dalila’s home, the set not only had great momentum but was full of symbolism.

Regardless of the production of Samson et Dalila, the moments when Samson pulls down the pillars were the most worth watching. In this version, after the child lead Samson to the columns, the pillars come down, the temple instantly disintegrating and collapsing in a process that was very stylish but one that also created a visual spectacle that was quite shocking.

Beyond the stagecraft, de Ana also designed a large number of the chorus actors’ body movements, making the stage show always seem to have a sense of movement. In addition, the Beijing Dance Academy graceful dance added to the opera’s ‘charm’ index.

Same review as above but with additional paragraphs at the end. Note: This is a computer generated translation that includes comments from José Cura. Cura uses words with precisions and imagery to effect. The computer does neither.

(Beijing Times)

José Cura is like a male god to the audience

Onstage, José Cura plays Samson as a warrior god. In fact, to the audience, Cura is considered one. When Cura appeared in the rehearsal, the audience exclaimed at once, and with emotion; I know someone who blogged, “José Cura appeared on stage like a moving sculpture,” which let the audience feel the kind of image he projects for Samson. In an interview, Cura said with a smile, “Twenty years ago, my body was stronger and I could go bare-chested (in the role) with a strong, muscular interpretation of the ancient hero. Now, I have to find the character’s spiritual interpretation to realistically portray the significance of the tragedy.”

As an opera singer, José Cura’s rich, powerful timbre makes him the model of the dramatic tenor. Explaining his unique sound, Cura said, “In my operas, I always think about what my voice is able to do and integrate it with a variety of elements. The voice is just one component a person can use. But even a better voice, if there is no character or charisma, has no meaning.”

Note: This is a machine-based translation. It is provided as a way to offer a general idea of the commentary but should not be considered definitive

Samson et Dalila – José Cura’s Divinity

Beijing Morning Post

10 September 2015

Li Cheng

[Excerpt]

After a taste of José Cura in Samson, the Latvian tenor was a mere mortal while Cura justified his reputation as a true ‘god.’

If you had been at the rehearsal for the B cast the day before, you would have heard a young Latvian with a powerful, dramatic tenor and certainly have been roused to rejoice that here, finally, was a good tenor! But last night at the premiere performance of Samson et Dalila with super tenor José Cura, we understood that the Latvian tenor was a mere “mortal” while José Cura is the true “god”! At the end of the opera, as he toppled the temple pillars, he sent out a burst of extremely powerful voice and generated a strong aura that was absolutely shocking to the heart and soul of the audience, so much so that after the curtain opened again there was ecstatic, almost Carnival-like cheer and applause to compliment the true “god.”

This is Hugo de Ana’s fourth production at the National Theater and he continued his realistic staging while adding more intention and symbolism. When the curtain went up, there were tall walls with steps in silvery black, the Jewish group wearing blue-gray toned clothing with stainless steel boxes, singing the opening chorus while dancing with the boxes, sometimes holding the boxes overhead, sometimes leaning on the ground with the boxes, to symbolize the agony suffered under the oppression of the Philistines. Then Samson arrives, the tall and burly José Cura, and in his first aria he had overwhelming power, his compassion for the Jewish suffering awakening his people.

The first surprise “jump” was the subsequent appearance of the Philistines, wearing helmet-like hats, exaggerated red and green costumes, the soldiers masked and the leader of the Philistines [painted], all looking more like characters from cartoons; then came the play on Chinese martial arts, immediately reminiscent of the “Journey to the West.”

Director de Ana’s design for the Philistine women were blue and green wigs, similar to anime, and colorful and gorgeous dress with exaggerated skirts, contrasting with the plain blue-gray clothes of the Hebrews.

José Cura, singer, conductor, composer, director, and photographer, is one of the world’s best Samsons. In the premiere he had a very different sound approach in every scene, so that his Superman-like character is full and strong. His grand, dramatic and explosive sound, enough to restore the “divine power” of Samson, allowed him at the last minute to bring down the Philistine temple and kill three thousand Philistines.

In a previous interview, Cura said that in the Bible story Dalila isn’t important but in the opera she’s charming and her allure is essential. The two Dalilas both have beautiful voices but in contrast the Dalila from B cast is sexier and more emotional while the one who partners Cura has more color.

Note: This is a machine-based translation. It is provided as a way to offer a general idea of the commentary but should not be considered definitive

Samson et Dalila with José Cura Ignited the Audience’s Innermost Feelings

Beijing Times

16 September 2015

[Excerpts]

Watching the opera Samson et Dalila at our home theater is a blessing, especially when able to hear José Cura sing and to witness his performance

Saint-Saëns’ Samson et Dalila recently premiered on the stage of the National Theater. When it comes to the opera, the voice I first heard sing "Mon cœur s'ouvre à ta voix,” the aria from the opera when Dalila tempts Samson in Act II, was soprano Maria Callas, whose voice charmed people. Later I collected the recording which moved my heart by Carreras and Agnes Baltsa.

In the National Theater production of Samson et Dalila, the singer playing Samson is José Cura, my favorite Argentine tenor. In this performance, his singing was most glorious, not only because of the open voice and the high notes suffused in golden light but in its proper dramatic grasp. Such is his vocal power, divinely manifested, that the loud, confident voice, the pianissimo is response to Dalila and the expressions of penance when he cries out to God, are all carefully managed. He could not help but make me think of Carreras and compare the two—the older generation was elegant and delicate, José Cura is solid and warm, both are equal. In performance terms, José Cura, from start to finish, had such boldness about him, whether he encouraged the Hebrews when he sang [Arrêtez, ô mes frères] or when he acknowledges his love for Dalila “May God’s lightning swift overwhelm me / I struggle with my fate no more! / I know on earth no power above thee” that it was the hearts of the audience that burned.

[…]

The dancers in the orgy scene were somewhat cautious [stiff], and perhaps this was the reason the dance seemed less able. A more meticulous choreography, more frenzied and elaborate, would be nice. As for the stage design, it cannot in general be said to be innovative but accompanied by the appropriate lighting, it had sense of mystery.

In short, being able to watch Samson et Dalila on our home opera stage was good fortune, especially to be able to listen to José Cura sing and to witness his performance.

|

%20lg.jpg)

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. It is provided as a way to offer a general idea of the commentary but should not be considered definitive

The Strong Man Sings: See Me in my Weakness

Ifeng / Beijing News

12 September 2015

The opera Samson comes to China for the first time with world-famous tenor José Cura in brilliant, magnificent voice

While many people are familiar with French composer Saint-Saëns’ Carnival of the Animals, his operas don’t have such high visibility. In fact, Saint-Saëns wrote thirteen operas. Among them, the story from the Bible of the Hebrew Samson composed as a three act opera known as Samson et Dalila is the epitome of his work and is also the only one included today as repertory in the world’s major opera houses.

From September 9 through 13, the National Grand Theater of China and Teatro Regio in Turin, Italy, will co-produce the opera Samson et Dalila premiering in Beijing. Renown conductor Jean-Yves Ossonce and the National Theater Orchestra join director Hugo de Ana, tenor José Cura and others to bring the magnificent music and visual magic of this wonderful French “Grand Opera” [to life]. It is reported that this opera, produced in China, will travel to Teatro Regio in Turin in the near future.

Performing as Samson for the first time in China is the world-famous tenor José Cura, whose magnificent, brilliant voice is filled with dramatic tension. Especially in the third act, in Samson’s famous aria “Vois ma misère, hèlas,” Cura sang with such a tearful voice and expressive interpretation that the listeners’ hearts broke. In the final moments, determined to take revenge after divine restoration of his powers, Samson pulls down the pillars and in the tragic moment sing the powerful high note to end the opera.

[…]

| Memories: From José Cura Official Facebook Page

|

Note: This is a computer-based translation. It is provided as a way to offer a general idea of the commentary but should not be considered definitive

José Cura’s Grand Opera Interpretation of Samson

Epaper/ynet

11 September 2015

[Excerpt]

On the international opera stage, the hero is often the dramatic tenor with the “golden trumpet.” Last night at the National Theater’s premier of the opera Samson et Dalila, the world-famous tenor José Cura gave the Beijing audience a chance to experience the genuine gold-trumpet tenor style: Cura plays Samson as Hercules (alternative translation: a god). From the very first act, he sang in grand opera style, filling the opera house above the orchestra and into every corner, allowing everyone to feel the power of Hercules.

Cura has performed Samson for twenty years, enabling him to understand the character so well that not every one of his arias are sung powerfully, as when he sings softly in response to Dalila’s temptations. Cura’s timbre is not the usual lyrical tenor we are used to hearing; he expressed feelings clearly and strongly, with formidable breath control that allowed him to sing loud and soft. In the Act III prison scene, he sang the aria, “Vois ma misere, helas!” with a volume went from weak to strong, full of emotion when singing pianissimo, full of the power of ringing bells while singing strongly, so this section of music struck the heart of the audience. Meanwhile Cura showed a strong stage interpretation of Hercules, showing both his sorrow and his anger.

What kind of French opera is Samson et Dalia? Is it magic or tragic? The director invited by the National Theater, Hugo de Ana, seemed to focus on the magic and therefore lost the inner lives of the characters; the play on the whole looked a bit messy. Adding so many Chinese elements to the choreography, spending so much time on fantasy, using shining sticks and metal frames as well as having Samson (shackled) to a silver pole while in prison, may have increased the magic in the performance but weakened the portrayal of the character’s innermost feelings.

Used to seeing realistic operas in Beijing, the audience seemed surprised in the face of de Ana’s fantasy. The staging at the end created discussion among the audience after the performance. Of course, everyone had an opinion but as one viewer said, “Thanks to José Cura’s interpretation, and to see José in this unfamiliar opera, it was worth it!”

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Legacy

Subscribe: https://www.youtube.com/@josecuralegacy/playlists

Available on iTunes and at Amazon

Resources

|

|

|

Visit at JoseCura.com |

Find Cura on Wikipedia!

This page is an UNOFFICIAL fan page. Mistakes found in these pages are our mistakes and our responsibility.

This fan page is dedicated to promoting the artistry of José Cura. We are supported and encouraged by Cura fans from around the world: without these wonderful people, we wouldn't be able to keep up with the extraordinary career of this fabulous musical talent.

Note that some of the material included on these pages are covered by copyright laws. Please respect the rights of the owners.

About Bravo Cura |Bio Information |Concerts 1 |Concerts 2 |Discography |Opera Works |Opera Work 2 |Press

Last Updated: Sunday, June 15, 2025 © Copyright:

Kira

%20lg.jpg)

%20lg.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%202.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20lg.jpg)

%20lg.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20lg.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20lg.jpg)

%20lg.jpg)

%20lg.jpg)

%20lg.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20lg.jpg)

%20lg.jpg)

%20lg.jpg)

.jpg)

%20lg.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)