Congratulations to José Cura

Principle Guest Artist

with the Hungarian Radio Arts Group

2019

|

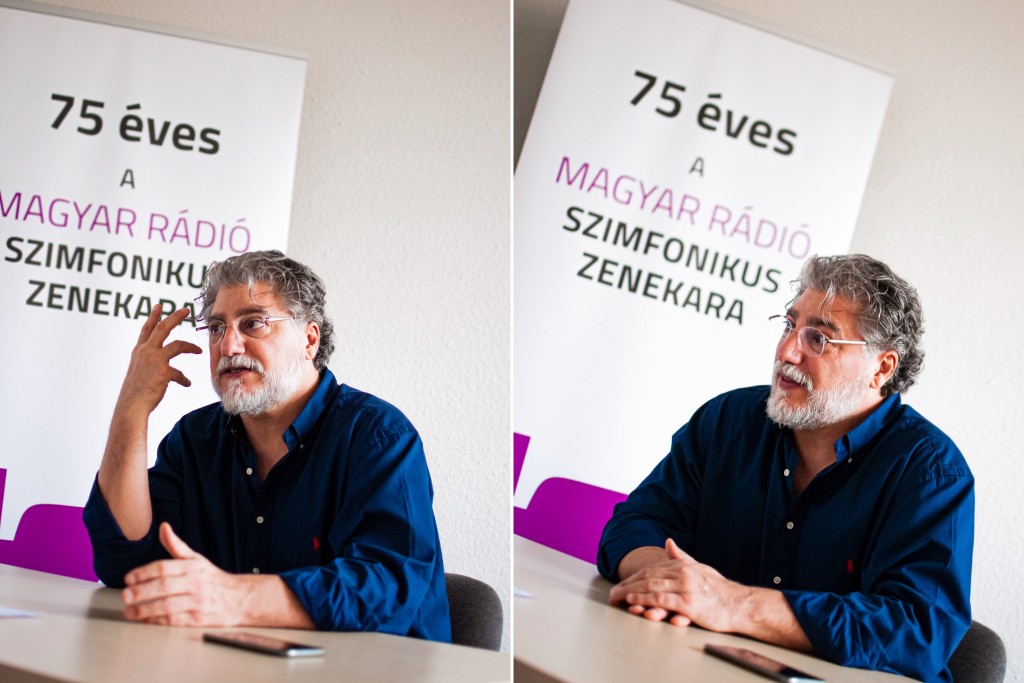

"A Show is Good when it's Intellegent" An interview with José Cura Operavilag Áron Tóth 27 December 2019 All photos by Jóború Adél for Léda Photography At the beginning of his three-year contract in Hungary, world-famous tenor José Cura talked about his career as a singer, conductor and composer.

– What was your motivation for the 3-year-long collaboration with the Hungarian Radio Art Groups? – It was love at first sight! When I first collaborated with them many years ago, we performed Zoltán Kodály’s Te Deum and Gioachino Rossini’s Stabat Mater. During our second collaboration, they performed my own music. If somebody shows so much love and interest in your own music, then the degree of emotional compromise is higher. At the end of the second concert, we were so touched by the nice experience that I was invited to join them as their Principal Guest Artist. – What factors did you consider when planning the program of the season? In fact, who chose the music pieces? For example, Verdi’s Messa da Requiem? – No, no, I didn’t choose any of the music pieces. Usually, an orchestra has a program to be fulfilled. When they invite me, they say: “We can do this, this and this. Which of these can you do? For which of these are you free? Which of these are you willing to do?” I may put my opinion on the program scheduled for 2022 or later; however, if the program is scheduled for 2019, you cannot change it for it is too late. In the present case, Requiem is one of my favourite pieces, and Verdi is one of my most beloved composers, so I said yes immediately.

– Despite having graduated as a conductor, you have gained recognition as an opera singer and have taken the stage the most as an opera singer. What challenges and difficulties do you face as a conductor? – The compromise is completely different when you are an opera singer. As an opera singer you are responsible mainly for yourself – if you are good, the quality of the whole thing grows; and if you don’t do a great job, the blame of your performance will go just on you. However, as a conductor, you are responsible for everybody; therefore, the degree of responsibility is higher and when things go wrong, you just cannot detach yourself from the overall responsibility. In the conductor’s case, the intellectual pressure is bigger, while in the singer’s case, a simple health problem can jeopardize your whole work. As a conductor, you don’t care whether it is cold or raining – you focus only on your job, and there is no such kind of pressure. Now, while the conductor is in charge of the whole performance, he needs to learn how to rely on his musicians, as well as the musicians need to feel they are in safe hands. Very easy to say, but not so easy to achieve. It is a rare chemical and technical formula. – During the rehearsals, do you happen to teach the soloists based on your technical knowledge, or do you focus only on the conducting? – There is nothing more unpleasant than a non-requested advice. Therefore, instead of teaching I make suggestions such as: “If I were you, I would solve the problem like this.” or “If my experience is useful for you, use it, or else, show me your idea..”. It may be advantageous for a singer to have a person in front who knows exactly what he, the soloist, is going through and what he needs. Should the soloists not follow my advice, I will not be angry at all. I am dealing with professionals, good professionals, not just beginners or students! – Since you are a highly recognised singer, how do you manage to instruct the soloists without making them feel you are criticizing or offending them? – Only the mediocre people take a piece of advice as an offense. If you are a “healthy minded” person, you understand the person is advising you because he has been in your place before and knows what you are going through. If a soloist takes advice as an offense, then his problem is not to fix that particular technical situation, but to fix his psychological complexes first!

– When you are invited to sing at an opera house, do you have the power to decide whom you want to sing with? – No, normally this doesn’t happen. When it is a big project such as a movie, of course, there is a conversation about how to combine all the great elements in order to have the best possible product. However, in case of a normal performance in the season of an opera house, you just work with the colleagues you encounter. In my opinion, it is great to meet new people all the time and make new experience by working with them. If you always sing with the same three or four singers whom you are happy with, you may be losing a whole universe of experience. Along the way you meet a lot of different people: from some people you absorb the good and from others you may learn what not to do. If you are wise, you can not only enrich your “luggage” with good experience, but also learn which things you have been uselessly carrying and remove them from your luggage. – Do you prefer classical production to modern production? – I prefer intelligent. I don’t care if it is modern or old, I just like productions which are intelligent. There are a lot of traditional productions that are really silly, and there are also a lot of modern productions that are really interesting, And the other way around, of course. It is like: “What do you prefer? Rembrandt or Picasso?” My answer is: “Listen, I prefer geniuses, and both of them are geniuses. That is the point!” A good director with something interesting to tell can do a good show regardless the production is modern or traditional. A bad director will create a bad show in any case.

– You are considered the most authentic performer of Verdi’s Otello and Saint-Saëns’s Samson. Did you intentionally pay special attention to these roles or is it just by chance that these have become your iconic roles? – First of all, I don’t think that I am the most authentic performer of these roles, because there are a lot of singers who do an honest job in portraying these two gigantic characters. However, it is true that I have done with these roles what I have done with all of my other roles: not what I was supposed to do… I went further, scratching the soul of these characters to see what else I could find there. One of the best reviews I have received in my life was supposed to be a negative review. “This damned habit Cura has of always doing what he wants, and not what he is expected to do”, a guy wrote after my Otello in the Metropolitan Opera in New York. For me it was one of the best reviews. While the critic intended to hurt, I believe this review was literally shouting: “Cura is being an artist, not a hooker!”. – How many times do you need to sing a role in order to know it confidently and fully? – Ugh, a lot! People keep asking me what the difference is between my first Otello in 1997 when I was only 34 years old, and my Otello now. When I was 34 years old, they used to paint my hair white to make me look older, and now they paint my hair black to make me look younger. It took “those” many years to understand what the character of Otello exactly needs. – If you had the chance to have a conversation with a historical composer, who would you choose, and what would be your question to such composer? – I would, for sure, choose Bach and my question would be: “How the hell did you do it?”. (Laughing.)

– In this season you are planning to sing Saint-Saëns’s Samson et Dalila and Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci. You also have a solo concert in your calendar. How do you prepare your voice for this strict and varied schedule? – It is busy but not as busy as it is used to be. I have done approximately 2,800 performances in my life so far. There was a period when I was doing more than 100 performances every year, meaning one performance every two days. This is not the case today. When you have reached a certain age, you shouldn’t stop singing but you should pay attention to have enough time for your body to recover from one performance to the other. The older you get, the more time your body needs in order to recover – and it has nothing to do with the technic. Of course, the technic helps, but if your body needs time you should understand the signals and provide that “requested” rest. You can probably run two or three marathons a week when you are 20 years old, but when you are 50 years old you can run only one marathon a month if you can run at all… – Do you still have a singing teacher? – No, I don’t. – Then how do you protect your voice? – Against what? I think I have a good technique – even if some people think the contrary – because after 30 years of singing, and singing those heavy roles you know, I am still able to talk… My technique may not be what people expect from me, but it is what I need. In addition, of course, you have to be wise and should accept you are not a kid anymore. You have to slow down your career and must not accept everything just for the sake of money. My alternative career as a director or a conductor is a blessing in that sense. Not to mention my work as a composer. These periods keep me in silence for weeks while I’m creating or orchestrating. – What are the common mistakes that opera singers usually make? – There is a very common mistake which is the consequence of the acoustic pollution of the modern times: it is the volume – shouting. People are deaf today due to the noise outside, the headphones and the high volume in pop concerts. When attending a concert, people do not have the same acoustic sensibility they used to have 50 years ago. Nowadays, the first impression of the people is that the performance is not loud enough. Even the young singers keep saying to me: “Maestro, if I sing in a beautiful, classy way, the volume is not enough. I need to sing louder and louder.” It is because of the acoustic atrophy coming from the modern public who needs more volume to “feel”, the same as they need more and more “fireworks” to be able to pay attention to a movie or a stage show. We forget that when we go to a concert of classical music, there is a direct experience from human being to human being, without subterfuges in between. It is an experience from me to you – from me, the human being on the stage, sweating, suffering, working hard, to you sitting down there. The people in a concert should feel they are listening to another person without intermediate gear, microphones, computers or something else. Arriving with enough time to the theatre in order to allow your ears to “focus” is also helpful. It is similar to taking some time to recover your sight to see with clarity after having been blinded by a strong direct light, for example.

– Next January, the world premiere of your opera entitled Montezuma and the Red Priest will be held at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music in Budapest, Hungary. You will be conducting the opera. How many years did it take for you to compose the opera? – It is going to be a tricky answer. In 1987, a friend of mine gave me a novel with a dedication on the first page: “I can see a very good libretto in this novel.” Back then, I was very young and had no experience in opera. I gave up since I didn’t know where to start from. 30 years later, in 2017, my daughter asked me: “Papa, shall we organise the library? It is a mess, and every time I need to look for a book, I will not find it.” During sorting the entire library, the little book came out again. I opened it and wrote the draft of the libretto in one afternoon. I said to my wife: “Wow! I am a genius, I wrote the entire libretto in one afternoon.” My wife answered: “You are mistaken, you didn’t write it in one afternoon but in 30 years.” She was right. It took 30 years of experience for me to be able to write down that libretto in one afternoon. However, I composed the music in two months in the summer of 2017. I left it to settle down to mature for one and a half years, and I took it again in 2019 to orchestrate it. Now it is ready to go, but I am sure that, after the premiere, there will be other adjustments. It is routine to do so. – Which musical era does have an influence on your own music: Baroque, Classical, Romantic or 20th-century era? – The people of our time are fortunate to have inherited the greatness of 500-600 years of music. To say I am influenced by only one era is so poor. The secret of today’s composer is to use all the elements we have inherited from the past, combine them and make something out of it. The only way to be original is not by trying to invent what has already been invented, but to shake all that experience into a big cocktail glass, have a nice drink, and bring it out through your own personality, which – by being different from others – is enough to make the resulting work unique. After Johann Sebastian Bach, there is nothing new under the sun, said a guy called Mozart… |

Cura for Charity

|

|

|

|

Charity Auction 2019 Hungary Sound Sculpture

|

|

|

|

7

Recording - Cura's

Ecce Homo, Budapest

|

I am glad to inform about my contract with the Hungarian Radio Arts Groups as their Principal Guest Artist:

Same text as Hirado

Same text as Hirado

Same text as Hirado

|

|

|

|

Same text as Hirado

|

|

Cura Interview on TV2

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

Interview

We have no idea what was being said (except for moving beyond the honeymoon period), but someone was having a GREAT time saying it!

|

|

Interview

|

|

Flashback

Budapest / 2003

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.

José Cura—Tenor of the Future

Fidelio Rita Szentgyörgy 31 October 2003

[Excerpt] Finally, a modern artist who knows how to make the audience love music! Finally, a handsome opera singer who can make us believe Cavaradossi's revolutionary impetus, Samson's energy, Alfredo's fiery love, Otello's insane jealousy. He also happens to have a Latin-lover appearance as divine as his silken voice, artistic originality, exuberant role creations and suggestive stage play. I was pleased to learn, mixed with disappointment, a few days before my departure that I would not be able to speak with José Carrera in Verona for a TV program. At the last moment he fell ill and “a certain” José Cura had jumped into the role of Don José in the Zeffirelli’directed Carmen. The balance of disappointment was “reinforced” by the skeptical commentary from the program’s editor-in-chief: “Cura? Who is he anyway?” But when I arrived in Verona and saw the performance, I was happy. Even today, I recall the rampage of the magical evening: the catacombs of the Verona Arena, the dressing-room, the sweaty shirt, the deep fire gaze of Cura, the full-being smile with the warm invitation to “Come, just come in, let’s get this over with right now!” While the make-up artist struggled to remove Don José’s beard, the young maestro answered my questions with the immediacy of a born charmer. We started the conversation with Cura’s Puccini Arias CD, conducted by Domingo. - Domingo is one of the best artists. Puccini's music has played an important role in our relationship. Since the Domingo Singing Competition [Operalia], which I won in 1994, he’s been following my career. We sang together several times at the Puccini Festival in Torre del Lago, which essentially gave us the idea of or producing an album based on Puccini’s arias. RS: The question of succession is often raised today… JC: It may be a good story for the newspapers to increase the number of copies sold when such headlines appear but it is unacceptable to me. Everyone has role models in their lives, but every artist has to go his own way. RS: Verona surely brings fond memories of your Italian debut at the Arena in 1993. And you unwittingly returned [as a substitute] for another legendary name for your Don José casting: José Carreras. JC: I have already sung the role of Don José at the San Francisco Opera. I have the utmost respect for the artistic qualities of Carreras, but everyone has to be accepted for their own art. I hope it doesn't sound pompous, but it's not a standard for me to be compared to anyone. Franco Zeffirelli also takes this position, otherwise he would not have offered me the contract. The above conversation took place in the summer of 1997, the year of Cura's debut at Ponchielli's Gioconda in Milan's La Scala. It was a triumphant year for the opera singer as he sang his first Otello in performance with Claudio Abbado. "José Cura: a new Otello is born," the newspapers proclaimed. The Hungarian audiences will now welcome the Tenor of the 21st Century at the Erkel Theater, the tenor who has been a recurring guest on Hungarian stages since that date. On 20 August this year he performed in Szeged, interpreting his favorite composers and on 28 October he will perform an evening of romantic arias and conduct the 9th Symphony by Dvorak at the Budapest Congress Center. Like all artists who have a great career, Cura’s story has not been ignored. Some biographies testify to the Argentinean’s reputation as a body-building champion. He admits he loves sports, body-building, football, horse riding and rugby. And like all great artists, he went through the school of life. He was born in Rosario, the second largest city in Argentina. He started playing piano and guitar and singing when he was 12. His original repertoire included pop, jazz, and spirituals. “You don’t have to over-mystify music. Mozart was the first bar pianist of his time,” he said with ease; he has been praised for her versatility and musical literacy. He still likes to compose and between arias he raises the baton as a conductor. This year has devoted much of the year to conducting symphonic concerts from Vienna to Sydney, Brahms to Beethoven. [In Argentina] he sang in the choir for years, and found opportunities to start a solo career closed. He was flying blind when, in 1991, he decided to start all over and move to Europe. At the age of thirty, he was a family man with a child in his arms and an ambitious wife, who currently runs JC Production, José Cura's Madrid-based agency. He also carried a letter of recommendation from his home teacher, conductor Horacio Amauri. Thus, his first journey led to Vittorio Terranova, a tenor who, as a teacher, was an expert in mastering the Italian melodramatic style. "It was so excellent," recalls Cura, “that two years later I was introduced to the Italian audience in Trieste.” So who discovered José Cura, who deserves the credit? Of course, the Italians are claiming that for themselves while the international press points to the famous Domingo singing competition for the discovery of the most promising talent in the new singing generation. “I didn’t arrive like a comet. My career is the fruit of many years of hard, purposeful work and determination to address people in the language of music. The successes, the fame, the money, the limelight did not make me… Verdi and Puccini's music made me an opera singer. I like to sing more dramatic roles because I am very interested in the psychology of dramatic heroes. I also have a lot to learn as a conductor. I aim for perfection. I will not settle for less.”

|

|

|

Last Updated: Saturday, September 12, 2020 © Copyright: Kira

%20BC.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)

%20BC.jpg)