Bravo Cura

Celebrating José Cura--Singer, Conductor, Director

CDs - La Traviata a Paris

|

|

|

|

|

|

Extended Play

|

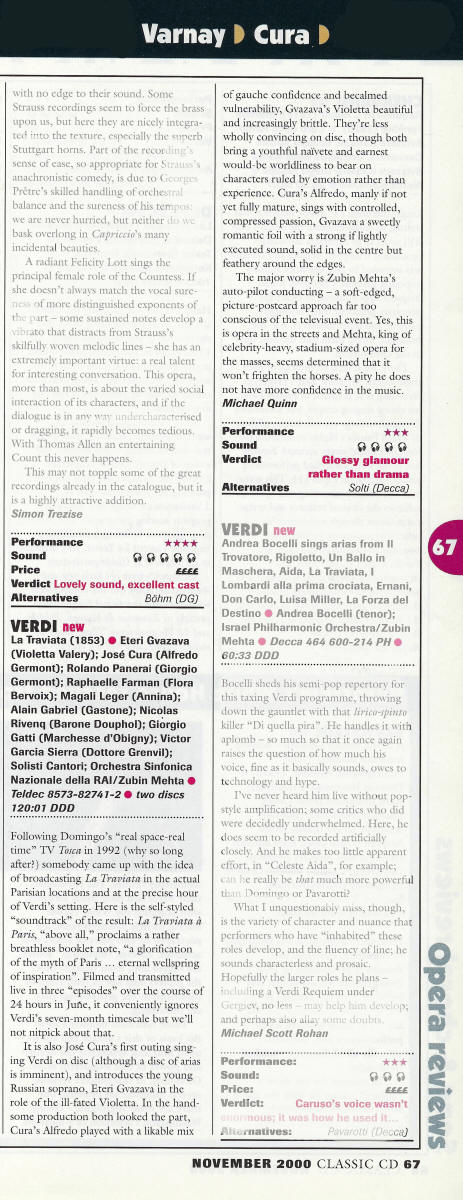

Verdi: La Traviata American Record Guide Lee Milazzo January 2001 A whole generation of opera lovers is being cheated as companies large and small prefer to engage performers who look their parts but can’t sing them. Teldec’s soundtrack for the film La Traviata a Paris is a perfect example of this misguided attempt to lure a new audience to opera. Eteri Gvazava’s smoldering beauty makes her a visual delight, but her weak, thin, unsupported voice makes her a vocal disaster. Only in a few quiet passages, such as the duet with Germont, does she actually sing the notes instead of skimming over, under, or around them (such a Sempre Libera you’ve seldom heard on record). Cura is a handsome Alfredo with so many holes in his attractive voice that he simply can’t convey what Verdi intended. Incredibly enough, Rolando Panerai, now 78 years old, actually sounds better than both soprano and tenor. Even when almost speaking his lines, his presence, technique, and experience allow him to create a living, breathing character (some of his music does sound tracked in in, however). In fact, almost every word and note from this great artist are a rebuke to his ill-prepared colleagues. Mehta’s energetic yet affectionate conducting and the excellent orchestra playing can not be faulted. But this glossy product is for movie fans only.

|

|

|

|

Tenors will be Tenors Gramophone Barrymore Laurence Scherer February 2001

Let’s just say that I’ve been taking the Cura. Despite José Cura’s apparent popularity as an operatic heartthrob, or perhaps because of it, he has been a problematic contender among tenors. Does he want to be taken seriously as an artist? I am of two minds over Cura’s latest pair of entries, the soundtrack from the live television production of La Traviata and the straightforward studio recording of Pagliacci. Certainly his Verismo disc was astounding for its sheer chutzpah. Given the Calvin Klein pose he assumes on the back of the box, one wonders if he strives to rival Domingo or Ricky Martin. Though the repertory was interesting it took second place to the singer’s own ego. Indeed, the singing itself—or crooning, to be more precise, seemed to be subordinated to Cura’s will to conduct the orchestra as well, which means the kind of studio trickery that Glenn Gould might have approved of. What’s worse, the conducting was ineffectual, with orchestral passages as slow as molasses and rubato at the important cadences exaggerated to the point of caricature. Yet, as if to prove how objective his baton can be, he cut his own phrases short at every important point. Cura’s more recent recital of Verdi arias suffers from the same misguided need to be all things to all listeners. John Steane very aptly compared the overall effect to being cornered by a relentlessly serious talker, whose expression never changes. From the opening measures of the first cut, Celeste Aida, whose recitative seems to emerge from a limitless postnasal cavern, we are treated to another dose of Cura’s mannerisms00there is crooning, there is sobbing, there are high notes popped out for special effects at the usual places. And he conducts himself—this time with the Philharmonia Orchestra its professional duty. By the time you get to the Forza scena, you feel that if Cura were also a clarinetist, he would have played those solos as well. That said, I am in two minds over Cura’s latest pair of entries, the soundtrack from the live television production of La Traviata and the straightforward studio recording of Pagliacci. Zubin Mehta conducts the former, pushing the score along as if he were fearful of falling behind the screen action (or obeying a click track). Here again, Cura generally croons Alfredo. Indeed, my impression is of a crooner pushing to imitate a big throaty tenor sound and ultimately achieving what Andrea Bocelli strove for in vain on his own disc of Verdi arias. Nevertheless Cura’s Alfredo is characterized by short-winded phrasing, hence the absence of a genuine cantabile line. The Violetta, Eteri Gvazava, was certainly chosen with an eye to the appearance on the small screen: she is lovely to look at. But her singing is thick and unfocused. She executes the ornamental line in Un di felice with an undisciplined technique that, together with the covered timbre of her voice, produces an almost horn-like tone evocative of ranz des vaches. Like Cura’s, her phrasing is curt. But together with this, Gvazava’s generally tentative approach to the music (possibly the most underwhelming account of Amammi, Alfredo on record) does suggest all too graphically a woman suffering from lung and throat ailments. It all boils down to this: if opera is to be perceived on the level of soaps, produced for an audience whose chief concern is in the story and the physical allure of the actors, this Traviata may be the way to go, regardless whether the die-hard cognoscenti agree or disagree. But on record, what counts is the interpretation of the music and the voices of the singers, and in these areas the present recording is no match for classic accounts. With his Traviata under my belt, it was with a furrowed brow that I played Cura’s Pagliacci. And to my surprise, I was won over. As Canio, he sings without crooning, and his thick, back-of-the-throat tone vividly suggests a man caught in the crisis of middle age. Moreover, there is evident thought given to his characterization. Barbara Frittoli offers a rather dark voiced Nedda—admittedly the aural heft does keep her Stridono lassue rather earthbound. Simon Keenlyside offers a virile, soaring Silvio whose voice blends seductively with Frittoli’s in the love duet, while Carlos Alvarez combines the vigor with a fine line in his convincing portrayal of Tonio. Chailly is a reformed soul here: conducting his generous ensemble with attention to detail and a sympathetic ear for the many nuances of Leoncavallo’s score.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Updated: Tuesday, October 27, 2020 © Copyright: Kira