Performed once in staged production and twice in concert format

|

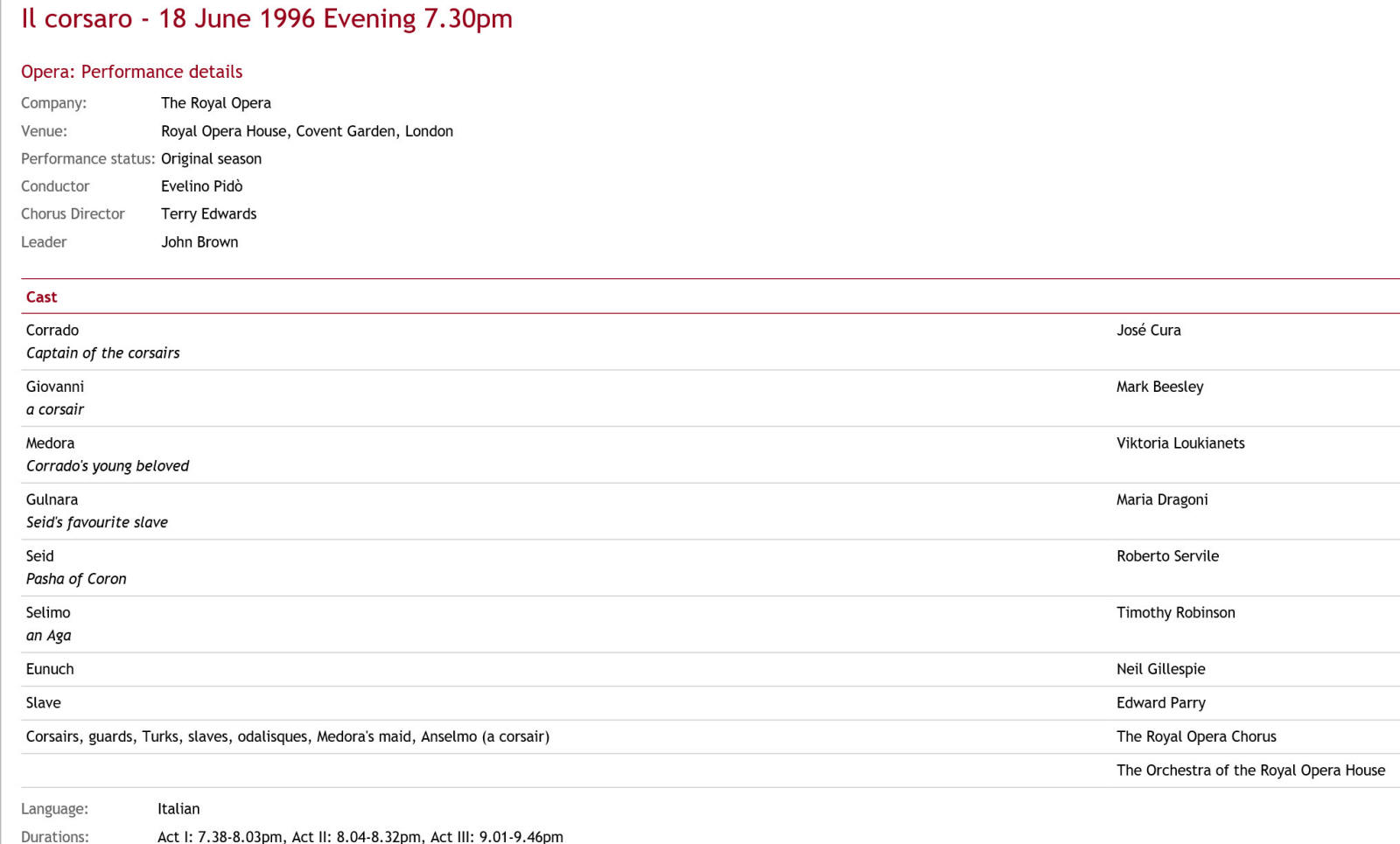

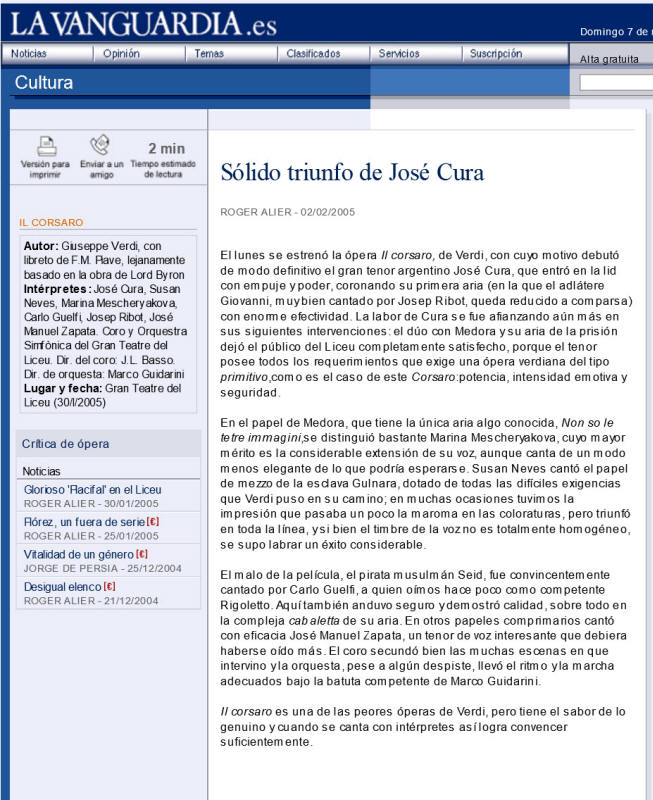

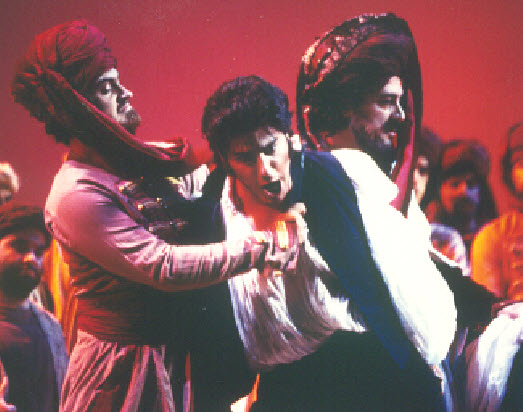

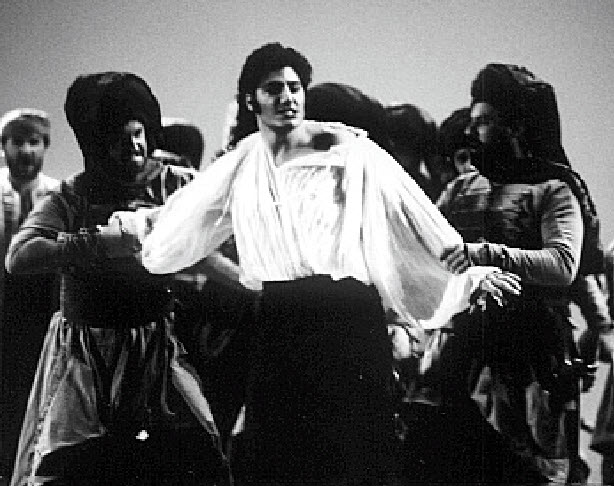

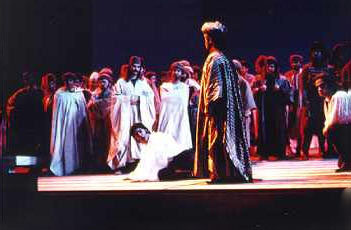

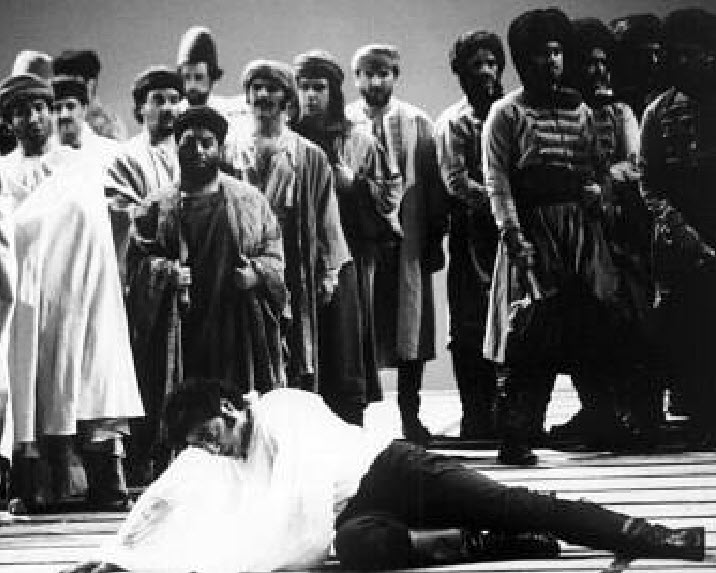

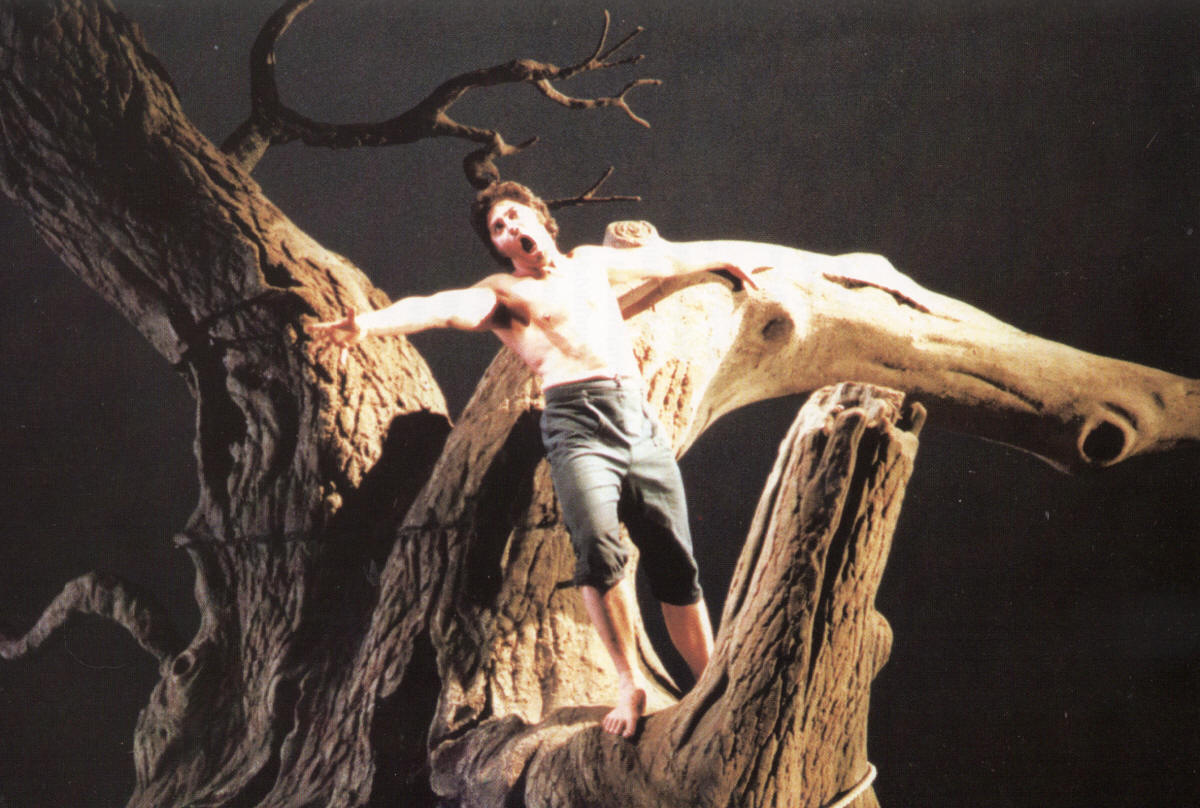

Il corsaro, Turin, February 1996: “Corrado, Il corsaro, is the Argentinian José Cura, who has today’s finest dramatic tenor voice (maybe the only one…?)” La Stampa, February 1996 Il corsaro, Turin, March 1996: “José Cura was authentically Byronic of profile in the title role—his Dervish disguise was based on the National Portrait Gallery painting—but Avogadro took little advantage of the tenor’s gift for rolling-eyeball acting, preferring to make him lope slowly around the stage in a meaningful fashion. At the end, instead of hurling himself into the sea, he just stood centre stage and looked thoughtful. Hmmmmm. Cura sang with the right mixture of dash and sensitivity—the prison scene went especially well.” Opera, July 1996 Il corsaro, Turin, March 1996: “Argentine tenor José Cura posed convincingly as the hero, and his dark timbre suited the moodiness of the character to perfection….” Opera News, May 1996 Il corsaro, Turin, March 1996: “On this occasion, José Cura (considered in some quarters as the new tenor hope) in the title role showed - as in all my encounters thus far - a sympathetic presence and an intrinsically interesting voice in need of further training.” CultureKiosque, March 1996 Il corsaro, Turin, March 1996: “José Cura survived with honors… ” L’Unita, March 1996 Il corsaro, Turin, March 1996: “All the singers were good, especially the two leads, Barbara Frittoli and José Cura, fresh and pure voices, who were a pleasure to listen to if only for the beauty of the timbre…” La Stampa, March 1996 Il corsaro, Turin, March 1996: “The Argentine tenor possesses a special voice, decidedly out of the ordinary. It is a voice with a particular timbre: masculine, sultry, with sensual streaks. Its center is dark but brightens and lightens as it rises. The youth and freshness can be used to hide the limits of a technique that can be defined as somewhat personal, not to mention questionable. The comparison with Del Monaco is, if anything, relevant in this aspect. Both use an unorthodox phonation, but one which, in spite of the technicalities, works. In addition, the Corrado of Regio di Torino’s Corsaro possesses the physique of rôle. When the prisoner appears tied to the trunk of a huge tree, which is a crucial scene, it is appropriate that he be naked from the waist up, displaying an athletic and powerful body, which is stunning: he makes an impression. He has the allure of a movie star and meets that need for image that has become an imperative in modern-day opera. This actor has instincts, credibility and charm. But the young Cura has another card to play: he has the momentum, the impetuousness, and the boldness that Corrado demands. He has all the elements needed to express the iconoclastic anger that is the distinctive characteristic of the Byronic hero, so imbued with the spirit of the romantic.” OperaClick, Giancarlo Landini Il corsaro, February 1996: “The Argentinian José Cura represents the great hope of modern opera.” Herald Sun, 21 February 1996 Il corsaro, London June 1996: “Tuesday’s concert started ominously with an announcement that José Cura was suffering from a throat infection but…he sailed through the evening unruffled… Cura with a properly Byronic mixture of energy and sensitivity. The beautiful dungeon scene, an oasis of calm amid all the swagger, went especially well-it is always good to hear tenor singing softly and sweetly.” The Times, June 1996 Il corsaro, London June 1996: “When a sick tenor (for whom apologies are made) sounds appreciably better than those in good health around him, then you're in trouble, big trouble. José Cura was that tenor, captain of the corsairs, heroically buckling his swash while discreetly expectorating into a ready handkerchief. He has quite a following among the Covent Garden cognoscenti - a tall, swarthy figure with a voice to match. The color of that voice - grainy, dark- hued - is arresting. But it's one colour, one dimension, without the interest of an instinctive, inquiring musicality. And without the natural resonance to sustain long, grateful phrasings, were they ever to be forthcoming. He should work on his legato and leave the trumpeting to look after themselves. But thank heavens for him. He alone sounded like he had any business on this stage - with or without the scenery.” Independent, 20 June 1996 Il corsaro, London June 1996: “Il Corsaro, given at the Royal Opera in concert form - reveals Verdi as already a master of melodramatic effect and incidentally provides a rewarding platform for the outstanding Argentinian tenor Jose Cura.” The Irish Times, Thu Jun 27 1996 Il corsaro, London June 1996: ““Tuesday’s concert started ominously with an announcement that José Cura was suffering from a throat infection but, with aid of much expressive brow mopping, he sailed through the evening unruffled.” The Times, June 1996 Il corsaro, London June 1996: “When a sick tenor (for whom apologies are made) sounds appreciably better than those in good health around him, then you’re in trouble, big trouble. José Cura was that tenor, captain of the corsairs, heroically buckling his swash while discreetly expectorating into a ready handkerchief. He has quite a following among the Covent Garden cognoscenti—a tall, swarthy figure with a voice to match. The colour of that voice—grainy, dark-hued—is arresting. But it’s one colour, one dimension, without the interest of an instinctive, inquiring musicality. And without the natural resonance to sustain long, grateful phrasings, were they ever to be forthcoming. He should work on his legato and leave the trumpettings to look after themselves. But thank heavens for him. He alone sounded like he had any business on this stage—with or without the scenery. “ The Independent, 20 June 1996 Il corsaro, London June 1996: “An announced infection explained this Byronic tenor’s frank, rather inelegant and oddly turned start. His charisma, familiar here, was expected to be the star ingredient. Later he rose to his challenges brilliantly, in the moulded phrased and golden trumpeting of his heroic final scene.” Evening Standard, 19 June 1996 Il corsaro, Barcelona, February 2005: “They put this opera on from time to time, whenever a famous tenor is eager to show his ability to give life to Corrado, the main corsair. And José Cura, the principle draw in the concert version of Il Corsaro at the Liceu, was eager to show his voice and dramatic temperament. He even kept our souls in tenterhooks during the evening with his glasses: now I put them on while the choir is singing; now I leave them on while I am singing; now I take them off as I am not singing; now I put them into their box. The Verdi master Carlo Bergonzi found shattered gold in the role based of elegance, sense of phrasing and control of the Verdi style. Cura opts for a different approach, one more direct and visceral, one taking advantage of the strength of his voice with its resounding center, its dark color, its attractiveness, the great dramatic appeal. A straightforward Corrado, thrilling without filigrees, greatly applauded by the audience.” Il Pais, February 2005 Il corsaro, Barcelona, February 2005: “José Cura, the star of the night, was comfortable in those passages where he was able to convert to the heroic voice with his explosive personal style. He sang his part in accordance with his musicality and temperament, with his trademark vision which can thrill and which, if lacking in the obvious tradition of belcanto, replaces the loss with an outpouring of high notes and glimpses of ornamentation.” ABC, February 2005 Il corsaro, Barcelona, February 2005: “Last Monday was the first performance of Verdi’s opera Il corsaro and also the official debut of the great Argentinian tenor José Cura. He entered the stage with vigor and power, completing his first aria with enormous effectiveness. Cura’s performance grew in quality through the rest of the opera: the duet with Medora and the prison aria left the Liceu audience totally satisfied, because this tenor complied with all the requirements of a Verdian opera of the “primitive” type such as this Corsaro: energy, emotional intensity and self-assurance.” La Vanguardia, 2 February 2005 Il corsaro, Barcelona, February 2005: “In the production at the Gran Teatre del Liceu, where regrettably the work was not staged, the vocal cast did justice to the score. In the starring role of the Corsair, we had the pleasure of enjoying the powerful voice of José Cura, who made a good beginning with his cavatina and offered a vigorous and energetic performance of the character. To his intense vocal performance he delivered theatrical expressivity, which compensated somewhat for his sometimes malleable phrasing. His success was overwhelming.” Crítica musical catalane, February 2005 Il corsaro, Barcelona, February 2005: “Not even the stellar presence of José Cura prevented the numerous holes found in this type of [concert] staging. The charisma and vocal presence of the Argentine tenor are beyond doubt but the concert provided evidence of technical limitations (unorthodox attacks, high note problems, sudden ending of sentences) and a style of singing much more comfortable in declamation than in careful phrasing. Still, the in the jail scene, the most interesting snippet in the work, Cura managed a dramatic internalization that was more than remarkable.” Avui, 2 February 2005 Il corsaro, Barcelona, February 2005: “The protagonist was the tenor José Cura, who sang his role with skill, teaching with his voice the beautiful colors of a lírico-spinto, the voice required for a hero who has to alternate between fierceness and tenderness.” Opera, 31 January 2005 |

|

José Cura, Mister Muscle Le stelle della lirica: i grandi cantanti della storia dell'opera Enrico Stinchelli 2002

The number of steps from the Pampas to La Scala may be shorter than expected: the feat has been accomplished by the new star of the heroic tenor repertoire, Argentine José Cura (Rosario 1962). A bodybuilder's physique, an Etruscan profile, great determination: here is the tenor of the 2000s, duly fit but at the same time musically highly prepared; that is, he is able to play piano, guitar, compose and even conduct an orchestra. In 2000 he was appointed Music Director of the Symphonia Varsovia Orchestra, inheriting the post that was held by the great Yehudi Menuhin: the first tenor in history to receive such an appointment. His voice is dark, emitted with élan and generosity, allowing him to tackle dramatic roles such as Otello, Sampson, Don Alvaro, Radames, in addition to more lyrical parts such as Cavaradossi, Don Carlos, Manrico, Corrado in Corsaro, even Alfredo in a very successful TV Traviata filmed in Paris and produced by Andrea Andermann. Thanks to his imposing figure and a certain boldness as a handsome man, Cura has established himself with audiences, especially female audiences, replacing the legendary figures of Del Monaco first and Domingo later in the hearts of true opera fanatics. On stage he imposed a new way of acting, with movements, gestures and postures not exactly usual for a normal tenor, all focused on the emission of the voice and the success of his own B-flat. "An actor who sings, rather than a singer who acts," this is the motto of the Argentine tenor, who is more attentive to stage interpretation analyzed with extreme thoroughness than to singing, implementing a method all his own, which can hardly be called orthodox. |

|

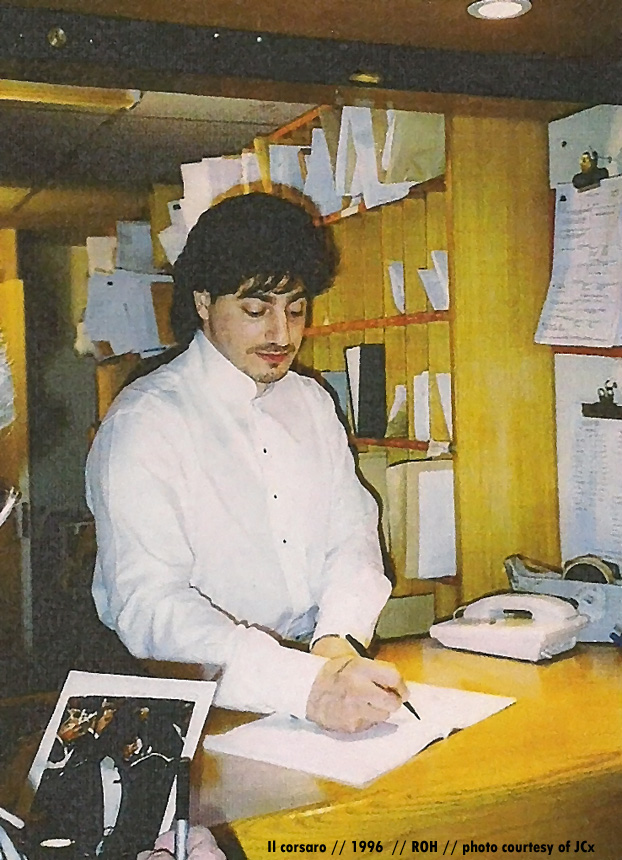

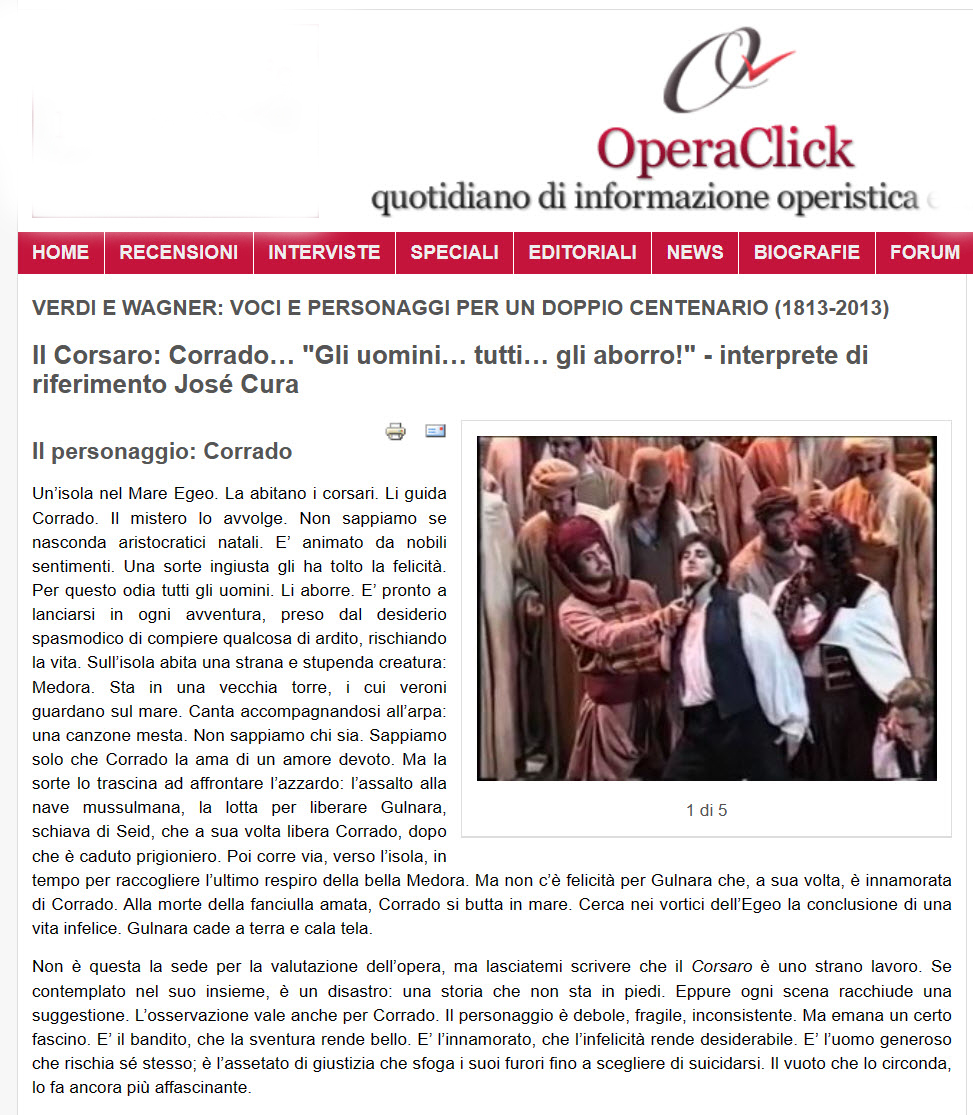

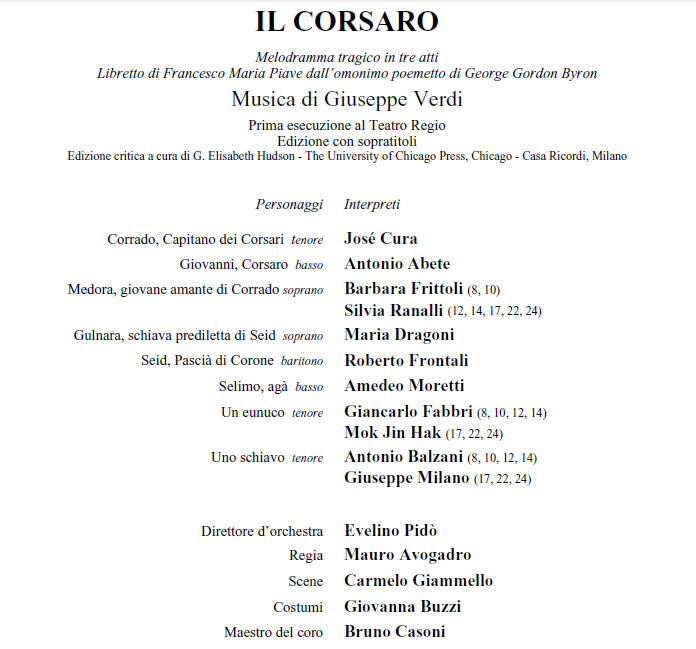

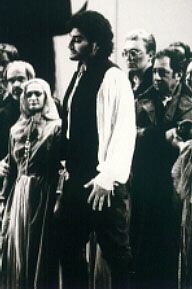

Il Corsaro: Corrado… "Men… all of them… I hate them!"Reference interpreter José CuraFrom Verdi And Wagner: Voices And Characters For A Double Centenary (1813-2013)Giancarlo Landini [Computer-assisted translation]An island in the Aegean Sea. Pirates live here. Corrado leads them. Mystery shrouds him. We don’t know if he is hiding an aristocratic birth. He is driven by noble intentions. An unjust fate has deprived him of happiness. That is why he detests all men. He loathes them. He is ready to embark on any adventure, caught up in the burning desire to accomplish something daring, to risk his life. On the island lives a strange and beautiful woman: Medora. She lives in an old tower whose windows look out over the sea. She accompanies herself on a harp, singing a sad song. We don’t know who she is. We only know that Corrado loves her with a devoted love. But fate leads him into a gamble: an assault on a Muslim ship, the fight to liberate Gulnara, Seid's slave, who in turn frees Corrado after he has been taken prisoner. Then they leave, returning to the island just in time to witness the last breath of the beautiful Medora. Upon the death of the beloved, Corrado throws himself into the sea, looking to the swirling Aegean Sea to end an unhappy life. There is no happiness for Gulnara either, who, it turns out, is in love with Corrado. She falls to the ground as the curtain drops. This is not the place to evaluate the work but let me just say that Il Corsaro is a strange work. If contemplated as a whole, it's a disaster, a story that doesn't stand up under scrutiny. Nevertheless, each scene carries a suggestion. This observation also applies to Corrado. The character is weak, fragile, insubstantial but exudes a certain charm. He is the bandit whom misfortune makes attractive. He is the lover whose unhappiness makes him desirable. He is the generous man who risks himself; he is thirsting for justice until he unleashes his fury and then commits suicide. The emptiness that surrounds him makes him all the more fascinating. The voice, the role and the vocality Il Corsaro was staged at the Teatro Grande in Trieste, today's Teatro Verdi, on 25 October 1848. It was a dud. The part of Corrado was written for Gaetano Fraschini, who increasingly enjoyed the composer's sympathies so much so that it is not wrong to say that this was the tenor Verdi identified with during his Galley Years. Corrado's voice is thus that of a stentorian tenor who sculpts the Recitatives, while in the cantabile in Act I “Tutto parea sorridere,” he collects the voice and stretches it in the phrase from the chiaroscurro of pianissimo to fortissimo. Bold momentum stirs the Cabaletta "Sì: dei Corsari il fulmine," which offers a fine example of forceful singing, with the need for a robust first octave and squillo at the top. As the protagonist in the encounter with Seid, Corrado vibrates with all the nobility of his soul; he touches a sympathetic chord in the great Duet with Gulnara and then finds moving accents in the Terzetto that closes the opera, before he ventures into the whirlpools of the sea, almost foreshadowing the Don Alvaro of La Forza del destino. A strong voice, then, for a robust singing called upon to embody the role of the unhappy, outcast Romantic hero. The interpreter: José Cura Abandoned by Verdi after its unfortunate premiere, Il Corsaro languished until, in the wake of the Verdi Renaissance, it returned to attention in the late 1960s. Then a series of successful stagings took place as evident by live performances (that of 1963, directed by Victor Wollny, with Bottion, la Battinelli, la DeNotaristefani, Carroli, in concert in Rome and that of 1971, directed by Franci, with Casellato Lamberti, la Mazzieri, la Papantonniou, Bruson, at Fenice), a studio recording (Phillips, conducted by Gardelli, with Carrerras, Normann, Caballe, and Mastromei), and a video (part of the Verdi Festival in Parma). To feed curiosity and interest, there is also the contribution of Katia Ricciarelli with her memorable and unsurpassed performance of “Non so le tetre immagini." My choice [to evalutate] is José Cura, who has frequented and continues to frequent the Verdi repertoire, to whom he also dedicated a recital, recorded for Erato. In this case, the reference documents are the 1996 concert from Covent Garden conducted by Evelino Pidò where he sang with Loukjanec, la Dragoni and Servile; the performance from the same year at the Regio di Torino, which this writer witnessed and where in the place of Loukjanec and Serve was Frittoli and Frontali. It also takes into account the most recent live performance, in Barcelona in 2005, which testify to a constant relationship between Cura and this work. The one in Turin was the Cura at the start; he had been in his career for four years. It was already a celebrated one. In 1995 he replaced José Carreras in the title role of Stiffelio, another part written by Verdi for Gaetano Fraschini and which Cura performed last month at the Monte Carlo Opera House. The Argentine tenor possesses a special voice, decidedly out of the ordinary. It is a voice with a particular timbre: masculine, sultry, with sensual overtones. Its center is dark but brightens and lightens as it rises. It is not expansive but suitable to the requirements of the score. The name of Mario Del Monaco, to whom he is frequently compared, comes to mind yet is is immediately evident that the two voices are essentially different. There is no doubt, however, that both find themselves at ease in Fraschini's vocality. Youth and freshness can be used to hide the limits of a technique that can best be defined as somewhat personal, not to mention controversial. The comparison with Del Monaco is relevant precisely in this aspect. Both use an unorthodox phonation, but one which, in spite of the questionable technique, works. It assured both of them fame and a very long career for the former and now more than twenty years for the latter. In addition, the Corrado of Regio di Torino’s Il corsaro possessed the physique of rôle. When the prisoner appears tied to the trunk of a huge tree, which is a crucial scene, it is appropriate that he naked from the waist up, displaying an athletic and powerful body: he makes an impression. He has the allure of a movie star and meets that need for image that has become an imperative in modern-day opera. This actor has instincts, credibility and charm. Corrado's tessitura poses no problems for him: it stays mainly in the center and does’t engage the high register beyond A. It doesn't require vocal prowess but does need strength. Without it, the recitative loses its penetrating force, the aria of Act I is reduced to nothing, the confrontation with Seid becomes trivial, the duet with Gulnara devoid of emotion. You can’t sing Verdi without power and Cura has it to spare. He says the word, captures the soul of the phrase. It is a characteristic that the Argentine tenor still retains today even after years of career that have seen his vocal means tarnish. The artist has kept his charisma intact. That was not enough: the young Cura had another card to play: he had drive and in that momentum he was bold. The role of Corrado requires such an approach. He had, in short, all the elements needed to express the iconoclastic anger that is the distinctive characteristic of the Byronic hero, so imbued with the spirit of the romantic On his part the whole Scene 1 of I Act takes on an obvious significance. Cura carefully shapes the short recitative with plasticity, then attacks the cantabile and gives it adequate prominence. Just listen to how he accents "l'aura, la luce, l'etere," realizing the marking of the central F envisioned by Verdi, thus compensating for the restricted dynamic play which bypasses the chiaroscuro to be realized with the sweetest sound. But let's be honest: no post-war tenor of stature has been able to unravel these passages—that is, those where a dramatic voice should bend to a mezza voce, with the exception, at least in part, of Franco Corelli, in the Battaglia di Legnano. To get an idea of grace singing in a stentorian voice one must refer to certain records by Francesco Tamagno. Apart from these stylistic-vociological disquisitions, Cura has an effect here, as in the subsequent cabaletta. His meeting with Medora evokes sympathetic and sensitive accents both in the andante mosso, "No, tu non sai comprendere," and in the stretta. In the first case it may be of interest to observe the precision with which Cura deals with the short melismatic passage that precedes "Andante meno mosso." In the second, the accuracy and here, as elsewhere, the cleanliness of the diction is striking: it gives us insight into the way in which the Argentine tenor makes Verdi's singing come to life from the spoken word. But the moment I would like to focus on is the great duet in prison, "Eccomi prigioniero!". The entire recitative is declaimed with intense involvment, illuminated in every word and chiaroscuroed with beautiful interplay of sound planes. Gulnara enters and Cura offers an esssay in conversational song, moving from the dreamy tone of "Sei tu mortal o spirto?" to the boldness of "Saprò morire," to the sweetness of "Un angelo!” which for a moment evokes the image of Medora, to the fierceness of "Cessa, Gulnara, lasciami" which preludes the desperation of "No, mi lascia..." up to “il destino a me fa guerra...maledetto sono in terra, la mia speme è solo in ciel!" where the final high note is impetuously grabbed. He tackles everything with an unorthodox sound that seems to come from the throat, but on this occasion he finds his way to a higher resonance, open, never coarse, always noble, encouraged by musical training as an authentic musician who uses it to achieve the desired effect. Then as the hurricane rages and Gulnara has left to commit her crime, the voice rings out strong, "Sul tuo capo discenda fero Iddio la tua folgore orrenda," with an undertone that makes evident the storm of the soul. In this passage Cura instinctively makes us feel the kinship that links this vocality to the still distant Otello, demonstrating the coherence of Verdi's production united by a single arc that encompasses it throughout. If that weren't enough, it's worth listening to how Cura intones "Or più di me sei misera." The dark colors of the center marry with the brightness of the center-high notes, while the phrase has just the right romantic inflection that suits the character. Those who like to explore the technique of singing can find an example of the voix sombrée, typical of the dramatic tenors of the 19th century, dark in the centre, as if the storm of the soul was stirring within, when suddenly the high note lights up with the glare of lightning as they pierce the clouds. |

|

Turin 1996

|

|

Il Corsaro in Turin Opera News Stephen Hastings May 1996 [Excerpt] There is plenty of action in Verdi's Il Corsaro, but most

of it lacks psychological motivation. The appeal of the Byronic hero

Corrado lies partly in his very mysteriousness, yet this was not the

sort of quality that fired the young Verdi's imagination. The work does,

however, contain a number of warming melodies and energizing cabalettas,

as well as a noble trio in the last act. It proved a great success with

the Teatro Regio audience (on March 10), aided by projected titles that

combined key phrases from Piave's libretto with plot summary.

|

|

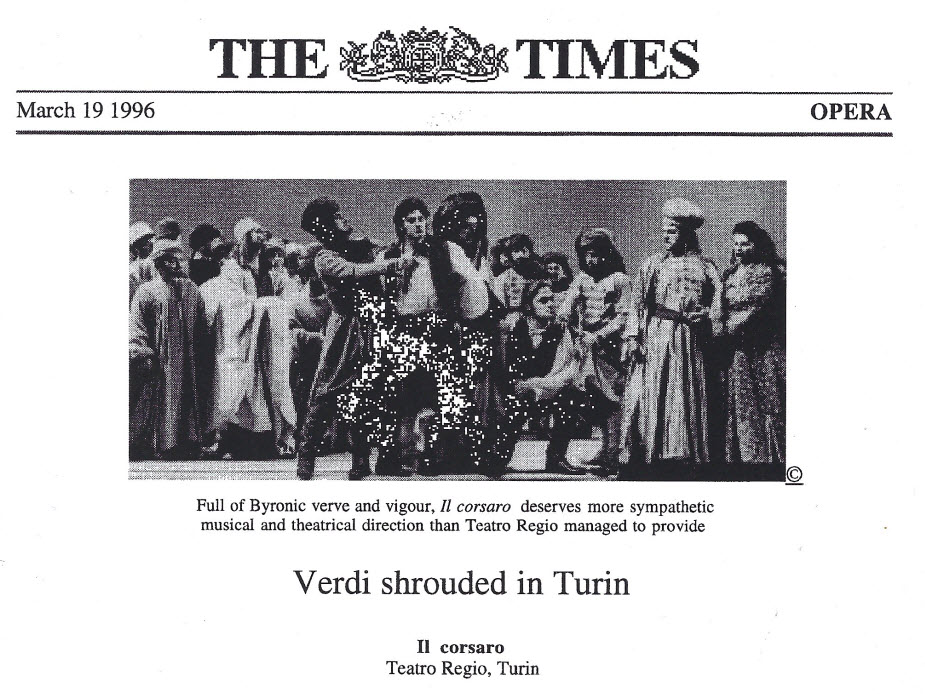

Verdi shrouded in Turin The Times Rodney Milnes 19 March 1996

The Royal Opera’s seven-year Verdi project shines brightly in an increasingly naughty operatic world—all 30-plus operas to be performed by the turn of the century, with both scholarly and entertaining ancillary events turning each summer’s six-week festival into a coherent artistic entity. Sadly, last year’s season was mounted under the Official Secrets Act; this year the ROH marketing department has swung into action with attractive ticket and accommodation packages, and with luck London will indeed become the Verdian capital of the world. But not precisely as planned. Financial cutbacks, which is what UK managements plan nowadays rather than seasons, led to cancellation of the new production of Il corsaro—Byron’s Corsair. It was to have been shared with the Teatro Regio of Turin, and previewed next month (instead we get another revival of Tosca) before joining the festival programme in June. The Teatro Regio went ahead on their own last week. What with this and the non-appearance of Mrs. Kong on the South Bank, Britain really is becoming the poor man of operatic Europe. It would be pleasing to report that the Turin Corsaro was a triumph beyond verbal description. Sadly, this was not the case. While it would be going too far to dub its loss to London a lucky escape, it is certainly not the end of the world. The piece itself, though, is almost pure gold: the combination of Byron and the young Verdi produces an opera of irresistible swagger and energy, tunes pouring out, the plot forging ahead at almost surrealistic speed. The Byronically alienated tenor hero, the two sopranos to whom he is a highly unsatisfactory love-object, the fire-breathing Turkish Pasha—it is a heady mix, swept along with music composed straight from the gut, and exactly what should have been stage at the summer festival to contrast with the grown-up Don Carlos. The lame substitution of two concert performances is little consolation. Mauro Avogadro’s production, in Greek War of Independence costumes, rightly stressed the Byronic content, taking advantage of José Cura’s strong profile: Corrado’s unlikely disguise as a dervish was based on the famous portrait in a turban. But Avogadro took little advantage of Cura’s gift for rolling-eyeball acting: this Corsair was made to lope slowly, meaningfully around the stage. At the end, instead of hurling himself into the sea, he wandered to the centre of the stage and looked thoughtful while the music went ape—directorial bloody-mindedness on an epic scale. There were compensations, including a harem pool full of decorously nude odalisques (Ingres going on Rubens), but they were not enough. Cura sang with a properly Byronic mixture of energy and sensitivity. The beautiful dungeon scene, an oasis of calm amid all the swagger, went especially well00it is always good to hear a heroic tenor singing softly and sweetly. Yet it is also the prison scene that occasions the qualifying “almost pure gold” above. The harem lovely, Gulnara, suddenly turns into Lady Macbeth and slaughters the Pasha, returning with bloody hands for a formal two-part duet. Form may dictate this but it is dramatically inept, the one tiny flaw in an otherwise stunning opera. Roberto Frontali was an appropriately stand-and-sing Verdi baritone as the Pasha, but both ladies—Barbara Frittoli as the melancholy Medora and Maria Dragoni as the spunky Gulnara—could have made stronger showings with a more sympathetic conductor than Evelino Pido. He hustled Dragoni through her florid music and failed to support Frittoli in spinning her long, elegiac lines. The cabalettas were taken too fast for their weight to be conveyed, and there was little wit in the harem music. It was all a little too polite. Pido is also in charge of the June concerts; perhaps the ROH management could slip something into his coffee and liven him up a bit.

|

|

Royal Opera House 1996

|

|

Verdi’s pirates bail out their leaking ship Evening Standard Tom Sutcliffe 19 June 1996 Il corsaro is a notoriously ugly duckling among early Verdi works. The composer loathed the impresario who commissioned it. He also lost faith in Piave, who was fashioning the libretto from Byron’s poem, the Corsair. But this 1848 opera has its moments. Close in tone to Donizetti, what makes it vital in Covent Garden’s Verdi festival, is the way it unveils original musical devices re-used and perfected much later. A whistling flurry of string notes in the overture describes the wind screaming through sailcoth, for instance, anticipating Otello. The three debutants at this concert performance, energetically conducted by Evelino Pido, had much to play with. The baritone Roberto Servile as Pasha Seid, later murdered in his sleep by his vengeful slave Gulnara (Maria Dragoni), produced a refined firm legato for his big act three number, though his top did not shine. For Gulnara’s sometimes almost elephantine music, Dragoni wove her mezzo in and out of chest voice—bumping over sleeping policemen. Her climactic response to Seid was (as Verdi asked) all gesture and no voice. Eyeing the challenge or an enticing trill, she repositioned her long black feathered stole on her shoulders first. But her duet with the Argentinian José Cura as Corrado, the pirate leader, was striking. An announced infection explained this Byronic tenor’s frank, rather inelegant and oddly turned start. His charisma, familiar here, was expected to be the star ingredient. Later he rose to his challenges brilliantly, in the moulded phrased and golden trumpeting of his heroic final scene. The most focused artistry came from his beloved Medora (a Ukrainian soprano, Viktoria Loukianets), her technique shipshape and intense. But she had little to do except take poison, despairing of Corrado, and die—prompting Corrado to jump off a cliff. The denouement is musically robust, but cursory theater.

|

|

Il Corsaro The Independent Edward Seckerson 20 June 1996

Lord Byron wrote the poem but I doubt he’d have recognized the opera. We’re talking here of Verdi’s “galley years,” where plot and music were more or less interchangeable, where what was good for the Israelites would do just as nicely for the Greeks or the Peruvians, where exotic was exotic whatever the location, on high seas or low lands, and the Italian “banda” tradition brashly held court in one trumpet-led unison after another. Il Corsaro is a pretty rum affair, full of eminently recyclable tunes (the furtive, lovelorn clarinet quick to make its appearance) and tremulous declamation. An overworked piccolo exults in its salty spray. Half a handful of character-forming arias are probably worth preserving from its compact hour and 20 minutes of music, not least the tenor’s Act 3 lament with its lachrymose viola and cello obligato. The final trio portends Rigoletto. But the opera needs to be fabulously sung if its’s worth exhuming for even a concert performance. And this miserable excuse for an evening couldn’t even manage decent. When a sick tenor (for whom apologies are made) sounds appreciably better than those in good health around him, then you’re in trouble, big trouble. José Cura was that tenor, captain of the corsairs, heroically buckling his swash while discreetly expectorating into a ready handkerchief. He has quite a following among the Covent Garden cognoscenti—a tall, swarthy figure with a voice to match. The colour of that voice—grainy, dark-hued—is arresting. But it’s one colour, one dimension, without the interest of an instinctive, inquiring musicality. And without the natural resonance to sustain long, grateful phrasings, were they ever to be forthcoming. He should work on his legato and leave the trumpettings to look after themselves. But thank heavens for him. He alone sounded like he had any business on this stage—with or without the scenery. Roberto Servile (as Seid, his antagonist) might regularly pass muster in smaller houses further down the international league table, but his dry, anonymous voice was conspicuously below par in this context. So, too, the young Russian Viktoria Loukianets as Corrado’s beloved, Medora. Now here at least was a singer displaying the kind of musicality so sorely lacking among the rest of the cast. A little precious, a little fanciful, perhaps, but sensitive, subtly inflected phrasings that actually meant something. What a pity, then, that the voice itself should be so anaemic—pale and uninteresting. All the colour, all the quality goes out of it in the lower dynamics. It all but disappears at anything less than mezzo-forte. Maria Dragoni (Gulnara) has plenty of that—and one can just imagine how exciting a prospect she must have sounded before the ravages of a plainly mismanaged career took their toll. The husky, Callas-like timbre is all that remains now. Vocal endearments are no longer an option. She gets by on vulgar glottal stops, an overworked chest register, and pneumatic top notes. It's a voice in distress. Which just about sums up the evening. Evelino Pido eagerly presided over a tired and overworked orchestra and chorus, springboarding into every jaunty, singalong accompagnamento in a fruitless attempt to kick-start the proceedings. One was grateful to have been spare a staging, but some of us would have welcomed the distraction. |

| “Il Corsaro, given at the Royal Opera in concert form - reveals Verdi as already a master of melodramatic effect and incidentally provides a rewarding platform for the outstanding Argentinian tenor Jose Cura.” The Irish Times, Jun 27 1996 Il corsaro, London June 1996: ““Tuesday’s concert started ominously with an announcement that José Cura was suffering from a throat infection but, with aid of much expressive brow mopping, he sailed through the evening unruffled.” The Times, Rodney Milnes

|

Barcelona 2005

|

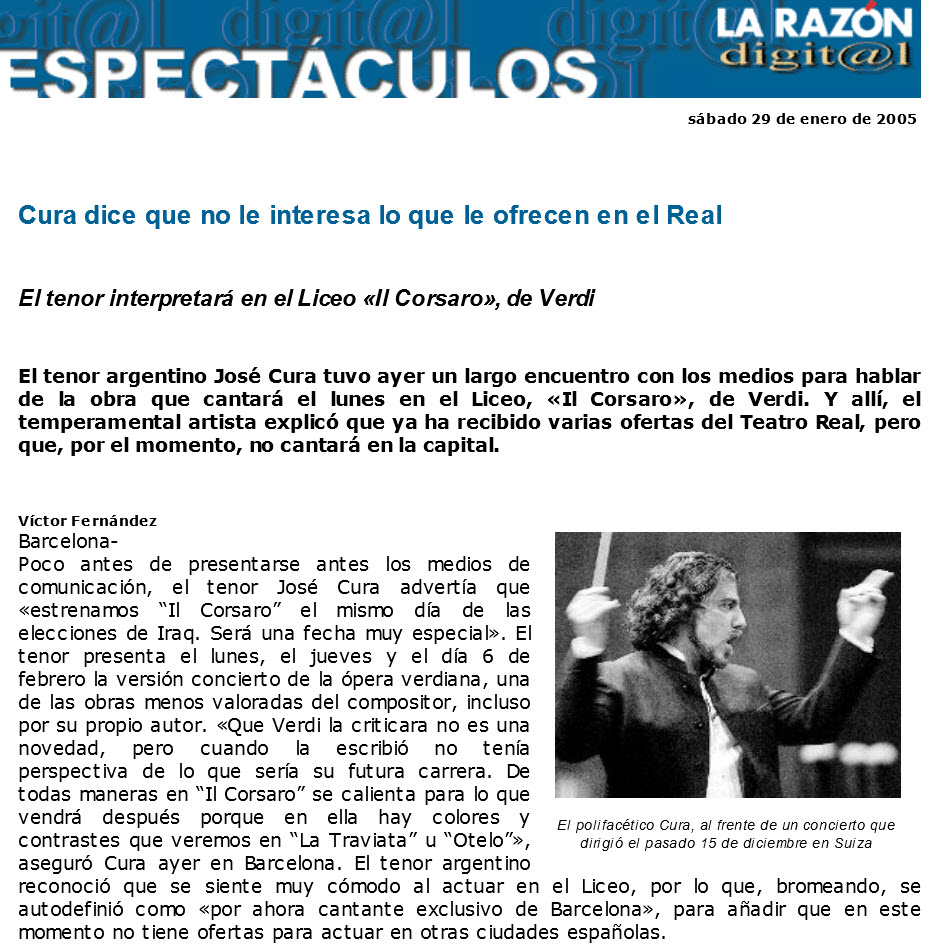

Cura says that he is not interested in what they are offering him at the Teatro Real The tenor will perform Verdi's Il Corsaro at the Liceo La Razon 29 January 2005 Victor Fernandez [Excerpt // Computer-assisted translation] The Argentine tenor José Cura had a long press conference with the media yesterday to talk about the work that he will sing on Monday at the Liceo, Il Corsaro by Verdi. And the temperamental artist explained that he has already received several offers from the Teatro Real but that, at least for the moment, he will not sing in the capital. The tenor will perform on Monday, Thursday and February 6 in the concert version of the Verdian opera, one of the composer's least appreciated works, even by its own author. “That Verdi criticized it is not news, but when he wrote it he had no perspective of what his future career would be. In any case, in Il Corsaro he warms up for what will come later because in it there are colors and contrasts that we will see in La traviata and Otello,” Cura said. The Argentine tenor confessed he feels very comfortable performing at the Liceu, jokingly defining himself as "for now an exclusive singer of Barcelona," explaining that he has no offers to perform in other Spanish cities at the moment. He added that "indirect comments that something is being prepared for the premiere" have reached him, in the sense that some would boycott his performance, although he did not consider the alleged threat important. Among his future projects, Cura said he is still in talks, after Montserrat Caballé's resignation, to work on José Luis Moreno's project, the future Coliseo de las Tres Culturas. “I recognize that it is a mammoth project. Moreno has offered me both the artistic and musical direction positions, but in the end, I decided to take charge exclusively of the musical section," he said. And he is still not sure he will return to sing at the Real soon. He admitted that there have been contacts with the new management, "but I want a return that does not cause controversy." For this reason he declared that the proposals received "did not seem fair to me, since they were experimental stage operations, which meant putting myself fully into the lion's den." Despite this, the Argentine tenor does not rule out that there may be solution coming soon because there have been ongoing conversations with Emilio Sagi, artistic manager of the Madrid theater. |

|

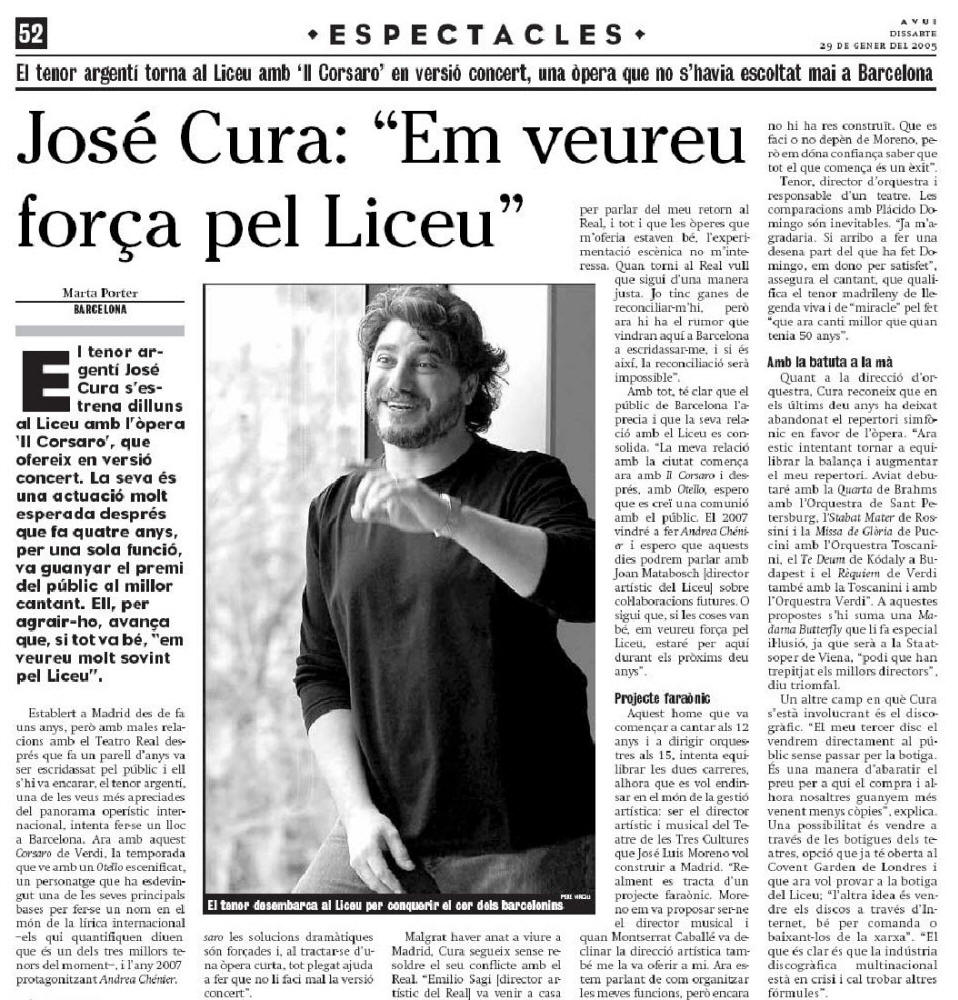

The Argentine tenor returns to the Liceu with Il Corsaro in a concert version—an opera never been heard in Barcelona José Cura: "You'll see a lot of me at the Liceu" Avui Marta Porter 29 January 2005

[Excerpt // Computer-assisted translation]

Argentinian tenor José Cura opens on Monday at the Liceu with the opera Il Corsaro, offered in a concert version. His is a much-anticipated return ever since his single performance four years ago for which he won the audience award for best singer. To express his gratitude he says that, if all goes well, "you will see me very often around the Liceu". Living in Madrid for the past few years but with a strained relationship with the Teatro Real after a confrontation with the audience a couple of years ago, the Argentine tenor, one of the most celebrated voices on the international operatic stages, is trying to make a place in Barcelona. First is this Corsaro by Verdi, then next season it will be a staged Otello, a character that has become one of his main roles in making a name for himself in the world of international opera (those who quantify such things say he is one of the three best tenors of the moment) and finally he will star in Andrea Chénier in 2007. Understanding Verdi About Il corsaro, an early opera by Verdi which, interestingly enough, is being presented for the first time at the Liceu, Cura believes that it is by no means "a masterpiece. There are many great compositions that are only hinted at here that Verdi will later develop in other operas such as La traviata, Don Carlo and Otello," but it remains an opera that is "very useful for understanding Verdi." Il corsaro also presents some vocal difficulties for a singer. "It has passages where a light Rigoletto-type tenor is needed and others where Otello's dramatic voice is called for. These constant color changes are very dangerous for the voice." José Cura, who has sung Il corsaro both in the staged version (in 1996 in Turin) and in the concert version (the same year in London), stated that "no work performs 100% in concert version, but in the case of Il corsaro the dramatic solutions are forced and, as it is a short opera, it is helped rather than hurt by the concert version". Despite living in Madrid, Cura still hasn't resolved his conflict with Teatro Real. "Emilio Sagi [artistic director of the Real] came to my house to talk about my return to Real, and although the operas he offered me were good, I am not interested in stage experimentation. When I return to the Real I want it to be in a fair way. I want to reconcile but now there is a rumor that some of them will come here to Barcelona to criticize me, and if that is the case, reconciliation will be impossible." However, it is clear that the audiences in Barcelona appreciate him and that his relationship with the Liceu is strengthening. "My relationship with the city begins now with Il corsaro and continues with Otello so I hope that a rapport with the audience will be created. In 2007 I will come to do Andrea Chénier and I hope that over the next few days I will be able to speak with Joan Matabosch [artistic director of the Liceu] about future collaborations. In other words, if things go well, you'll see a lot of me at the Liceu. I'll be around for the next ten years." Massive project This man who started singing at the age of 12 and conducting orchestras at the age of 15, tries to balance the two careers and also wants to enter the world of artistic management: to be the artistic and musical director of the Teatre de les Tres Cultures that José Luis Moreno plans to build in Madrid. "It really is a massive project. Moreno proposed that I be its musical director and when Montserrat Caballé declined the artistic direction he also offered it to me. Now we are talking about how to organize my functions, but as of now there is nothing built. Whether it ever gets done or not is up to Moreno." Tenor, conductor and manager of a theater: comparisons with Plácido Domingo are inevitable. "If I manage to do a tenth of what Domingo has done, I will consider myself satisfied," says the singer, who describes the Madrid tenor as a living legend and a "miracle" because "he now sings better than when he was 50 years old." With baton in hand As for orchestra conducting, Cura acknowledges that in the last ten years he has abandoned the symphonic repertoire in favor of opera. "Now I'm trying to balance the scales again and increase my repertoire. I will soon debut Brahms' Fourth with the St. Petersburg Orchestra, Rossini's Stabat Mater and Puccini's Missa de Glòria with the Toscanini Orchestra, Kódaly's Te Deum in Budapest and Verdi's Requiem, also with Toscanini and the Verdi Orchestra." To these proposals is added a Madama Butterfly that he is particularly excited about, as it will be at the Staatsoper in Vienna, "a podium that the best conductors have stepped on," he says triumphantly. Another field in which Cura is getting involved is the record industry. "We will sell my third album directly to the public without going through the store. It's a way to lower the price for those who buy it and at the same time we earn more by selling fewer copies," he explains. One possibility is to sell through theater shops, an option that is already open to Covent Garden in London and that he now wants to try in the Liceu store. "The other idea is to sell the discs over the Internet, either by order or by downloading them from the network. What is clear is that the multinational record industry is in crisis and other formulas must be found."

|

|

Argentine José Cura Premiers Verdi’s Il Corsaro in the Liceu The tenor takes the lead role in the performance of the play previously unperformed in Barcelona El Periodico Roger Pascual 31 January 2005

[Excerpt // Computer-assisted translation]

José Cura (Rosario, 1962) could be reproached for many things but never for being a domesticated tenor. On the contrary. He is one of those artists who must leave their imprint in everything he does and he backs down, as he demonstrated in December of 2000 when after being booed by some people from the pit of Madrid’s Teatro Real, he stopped the performance of Il Trovatore and confronted them.

That’s why, despite having heard rumors that those who rebuked him were preparing "something" for tonight's premiere of Il corsaro at the Liceu, he seems very calm. "In Barcelona this is not possible," says Cura, who hopes that the performances of Il Corsaro and next year's Otello will help create a bond with the audience that will allow him "to be bothering people around here for a long time."

Inspired By Byron

Inspired by a poem of Lord Byron, Il corsaro, which has never been performed in the Liceu, is an opera not immune to criticism, starting with those of its own composer, Giuseppe Verdi: “Il Corsaro must be looked at from the perspective that it was a transitory work in which Verdi hinted at things he would later develop in La Traviata and Otello”.

As a tenor he considers it as “a very demanding work since it combines moments which require very low registers while having a very dense orchestra and other very light moments in which one is scarcely accompanied by a harp, a violin or a flute.” Beside him Josep Ribot, Marina Mescheryakova, Susan Neves, Carlo Guelfi and José Manuel Zapata complete the cast of the concert version of this opera under the conductorship of Marco Guidarini.

Cura and Plácido Domingo, who is performing Parsifal, will share the Barcelona nights in the theatre this week. It is an event that does not lack significance if we bear in mind that since his leap into to the first league in opera, Cura has always been compared to Domingo: “If I was one tenth so legendary and mythical as he has been and is, I could sleep in peace,” says Cura, who places the recently deceased Victoria de los Ángeles on the Olympus of opera.

The artist, who started to sing at the age of 12, to conduct at the age of 15 and made his debut in opera at the age of 30, hopes to “balance his career,” and therefore has plans to strengthen his conductor side and also considering moving into the field of programming if José Luis Moreno’s project of the Colieso de las Tres Culturas finally bears fruit: “It is a grandiose project. We’ll see if it develops.”

True to his reputation of enfant terrible he has chosen to allow his latest album to escape the usual distribution circles and is betting on the Internet: “The most logical thing would be if the points of sale placed the songs according to their quality and not according to how much is given to the salesperson.”

Finally, the singer gives a key to understanding the emergence of great tenors from South America like Juan Diego Flórez and Marcelo Álvarez: “There is a need to fight, a rage to go all out, which does not exist in the first world because young people are installed in comfort.” |

|

José Cura stars in the premiere of Verdi's Il corsaro at the Liceu La Vanguardia Marino Rodriguez 29 January 2005

[Excerpt // computer assisted translation] This is the official debut of the Argentine tenor at the Gran Teatre after an unexpected performance of Samson et Dalila in 2001 Inserted between performances of Parsifal, the Liceu will offer (Monday, Thursday and Sunday) a concert version of Il corsaro, one of the few operas by Verdi that has never been heard at the Grand Theatre. In addition to this welcomed premiere the other great draw of this tragic and romantic melodrama, inspired by the homonymous poem by Lord Byron, is the participation of the Argentine tenor José Cura, who sings the main role—Corrado, the captain of the corsairs ...

Cura, who is 42 years old, is one of the most notable tenors of his

generation and while this can be considered his official debut at the

Liceu, he previously took part for a single performance in Samson

et Dalila in 2001 after José Carreras fell ill. It was

a one-off performance but a triumphant one and it earned him the award

from the Liceistes de Quart i Cinquè Pis li van concedir for the best

singer of that season.

Speaking about Il corsaro, Cura believes that "it is

clear that it is not a masterpiece, but it is an interesting work and

one that every good fan of opera should listen to sometime, since Verdi

experimented with many things in it that he used later. Thus, there

are bars from Traviata, phrases from Don Carlo

and colors from Otello. For the tenor it is not an easy

work because it contains very serious moments with dense orchestration

contrasted by other light ones with little instrumentation... Although

no opera delivers one hundred percent in concert format, I think that

in this case it is a good option to do it this way.”

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)