Bravo Cura

Celebrating José Cura--Singer, Conductor, Director

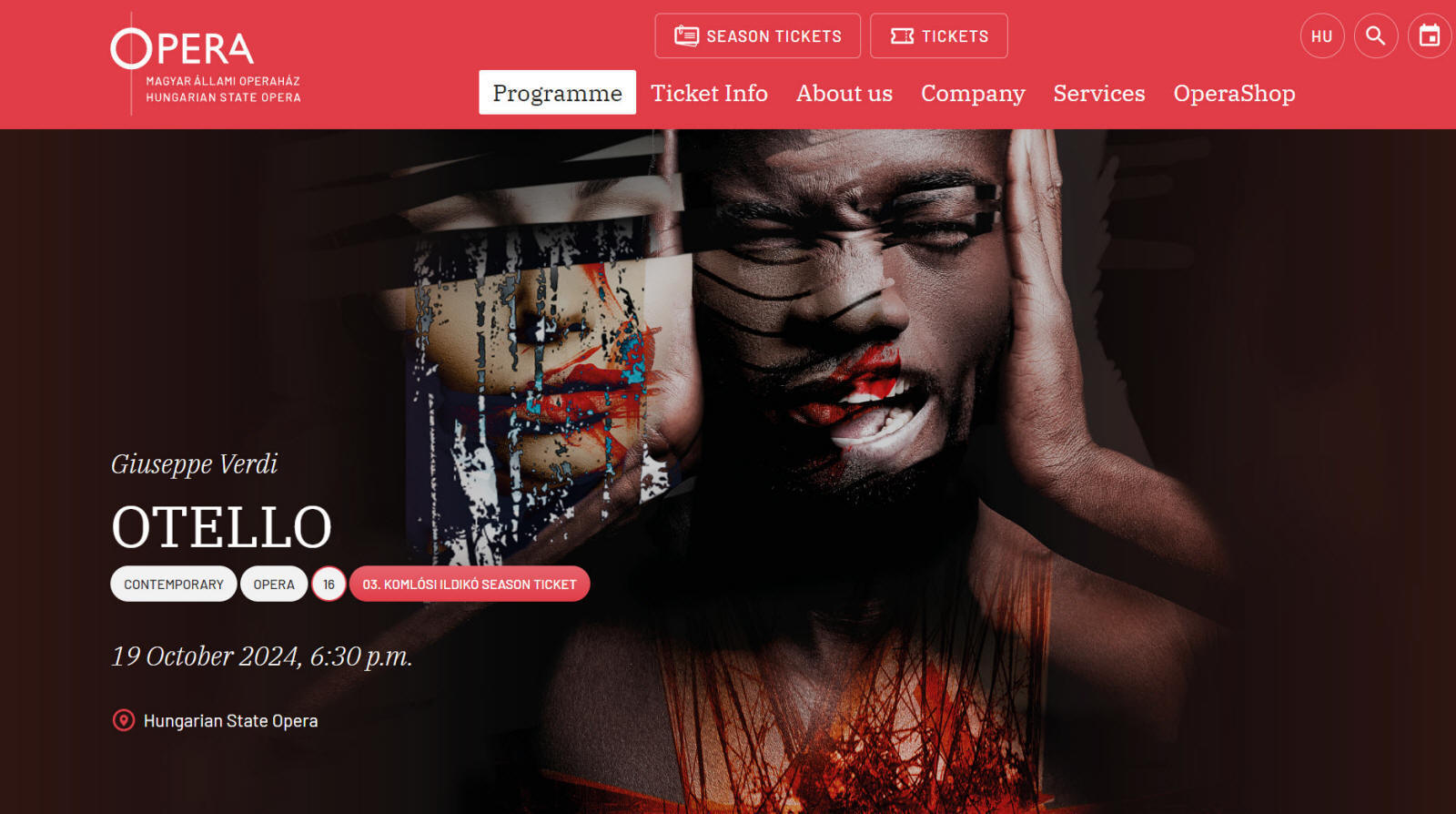

Operas: Otello

Otello -- Budapest October 2024

José Cura performance dates: 19, 22, 26, 31 October

Other tenors will appear as Otello on 24 October and 3 and 10 November; the names have not yet been listed on the website

|

Otello at the Hungarian State Opera Opera Diary Geoffrey Leave 19 October 2024

[Excerpt]

My excitement was through the roof for a second Otello performance in as many days, especially since Otello is my favorite opera. But sadly, the best part of my night in Budapest on October 19th, 2024, was the McDonald’s and beer I had afterward. What should have been an unforgettable evening was a complete disappointment from start to finish. Stefano Poda’s staging brought nothing to the production. It was static and unimaginative, which, for Otello, is unforgivable. I usually appreciate his work—his Aida in Verona was a fantastic and thoughtful production—but this felt like a lazy attempt with no real vision. The result was a performance that was painfully dull, lacking any dynamism or depth. How can Otello, one of the most dramatic operas in the repertoire, end up feeling so lifeless? The audience made things worse. From where I was seated in the orchestra, people in the boxes kept chatting throughout the performance, which completely shattered any immersion in the story. It was like being in a train station, not an opera house. Then there was the music itself. Where do I even begin? The orchestra was consistently off-key, and the coordination between the conductor and the musicians was a mess. The timing was off, with sections either rushing ahead of the singers or lagging behind. The disarray was palpable. Casting was another major issue. How do you cast a team of second-rate singers alongside the legendary José Cura as Otello? It felt like placing a Division 10 football team next to Zidane. The Jago was a disaster—his Italian was shaky, his rhythm was all over the place, and his performance was flat, lacking any menace. He was the least convincing Jago I’ve ever seen. And Desdemona? She was too young, lacked depth, and failed to inspire any empathy. Honestly, at one point, I thought I was in some sort of hidden-camera prank. It was that bad. I kept waiting for the performance to stop, for someone to say it was a rehearsal or a mistake, and to restart the show properly. I had flown in with high hopes, arriving by plane at 5 p.m. for the 6:30 p.m. performance, only to leave the next morning completely let down. It was a waste of time and money. The only redeeming factor of the night was, unsurprisingly, José Cura. His charisma and sheer presence in the role of Otello showed why he is one of the great tenors. He has performed the role across Europe, and his experience shone through, despite the weak cast surrounding him. Bravo, Mr. Cura! Unfortunately, even his brilliance couldn’t salvage the rest of the disaster that was this evening’s performance.

BC: Could someone kindly explain what these folks have to do with Otello--in the context of the libretto, at least? OK, so maybe they represent the Turks Otello just battled? If so, these blood covered, aggressive, violent naked folk did nothing to evoke sympathy or to show reason why we should take pity on them and condemn Otello to purgatory for just doing his job....

|

| Out of the black of night...now just imagine how much darker it was when the scrim was in place and when any of the principles left their little spot of light.... The entire opera featured light too bright, light too dim, light too unsettled. It's hard to feel any sort of emotion for anyone whose face couldn't be seen or who appeared and disappeared depending on the precise placement on stage. Even pulling out the trusty binoculars didn't help much but added even more distance between actors and audience. Obviously painting a stage with light is an artistic decision, but this desire in Budapest to replace visibility with mostly black augmented with a few spots of white was a decision made by the director with no thought at all about how the audience would fare. Maybe he didn't care. After all, as he says in the program notes, (paraphrased) nothing on stage has to be representational as long as the music is allowed to speak. That philosophy gives freedom to the director to create mayhem and then discount criticism because the music carries the story--even if that is not completely true in opera, which is sung DRAMA with an implicit requirement for coordination between music and movement. |

| Better from the camera than in the theater; from our seats, the love duet was as dark as Desdemona appears in this photo, probably due to the distorting affect of the scrim. And don't ask about the hands; they were a topic of general conversation and no one could figure them out. Guesses include they represented all the people Otello had killed, but then war is war and we are all guilty of crimes against each other. Others said it was the eternal helplessness of the doomed, sending a warning; if so, nobody was listening. |

Rehearsal Photos

Cura interview in Opera

|

José Cura: "As a director, I don't give in to the tenor" Opera Magazine Tamás Jászay October 16, 2024

[Computer-assisted Translation]

José Cura - photo: Szilvia Csibi The globe-trotting Argentinian singer, conductor and composer José Cura is almost welcomed home by the Hungarian audience: in autumn, we had the opportunity to observe his directing skills as well as his role-making abilities. In our interview, we also wondered whether Otello and Cavaradossi had anything in common. - You debuted on the Hungarian stage in 2008 in Szeged in the title role of Otello. In an interview, you said: "When I first sang Otello at 34, I could only imagine how a man of 45-50 would feel in that situation... It brings a whole new way of approaching the role that I've arrived at the character." Since then, you have met the Moor from Venice countless times. How do you see him now? - I have always read this work from a Shakespearean perspective, that is, without the patina of nobility that Verdi's music seems to convey. The key word here is 'seems,' as the music displays all the psychological aspects of the character. This, of course, only becomes clear if we really immerse ourselves in it, rather than simply duplicating what others have already tried. One of the recurring criticisms I get during my long relationship with the Moor is that my approach to the role is unique... But of course! The performer deserves the title of Artist precisely because of his uniqueness; so, in capital letters. In any case, my years with Otello have confirmed many of my guesses and suspicions, and the experience of many years has helped me to rethink and polish certain ideas. – In October, the Opera will once again stage Stefano Poda's 2015 production, which stands out among the Otello productions with its striking visuals and symbolic language. What challenges do you face in preparing for such a performance? - The director is renowned for his masterly crafted works, where the audience is touched by the intelligence of the stage aesthetic from the moment the curtain rises. Admittedly, I've never worked with Stefano Poda before, so I'm eager to discover the director behind the breathtaking set design. - Love, intrigue, death - the fictional biographies of Otello and Cavaradossi overlap at several points. As an expert on the operas of Verdi and Puccini, what similarities do you see between the two roles? - There are hardly two characters and stories that are so different. Scarpia is not a traitor, he never hides his intentions: he deceives Tosca, but all those who work in espionage, such as Cavaradossi, know very well what is going on. Tosca is no Desdemona! Yes, they are both young and seem rather naive, but while Tosca represents more of the comic side of the hysterical diva, which helps her to portray the real woman, Desdemona is a strong young woman who stands up to her father for her love of Otello, even sacrificing her life for him as extreme proof of her devotion. Cavaradossi dies for his convictions when he bravely defies Scarpia and his men.

Otello is a Muslim convert to Christianity who wants to make a career in Venice, and in doing so, he sets out to kill his fellow Muslims, the Turkish Muslims. He is an apostate and a traitor, haunted by the suspicion of betrayal of his wife and Cassio, who mistreats and then kills Desdemona. While Mario bravely faces death, Otello escapes human justice by committing suicide, adding cowardice to his other sins. We could spend hours analyzing the factors that lead him to do so, but the facts remain the facts. For me, what is really fascinating is that these details appear not only in Shakespeare's drama, but also in Verdi's music and Boito's remarkable libretto. The latter is sometimes even better than the Bard's play... – Cavaradossi is one of your emblematic roles, and you staged Tosca in Denmark in 2023. Were there any disagreements between the director and singer José Cura? Does directing the same production you usually sing in cause any internal conflict? - The truth is that when I sing and direct, I'm my worst nightmare... I don't give in to Cura, the tenor, because that would mean that I would then have to leave my colleagues who I direct run as well. The good news is that after forty years in the business, I know pretty much what works and what doesn't, especially with singers, so I refrain from pretending to be useless. – At the beginning of September, a semi-staged production of Tosca was staged in Pécs, performed by the Orchestra and Choir of the Hungarian State Opera House. What comes across more strongly in the hybrid form, and what do you have to give up as a director? - In a performance like this, it's not about compromises, it's about accepting that you have to stage the work differently, sometimes because of budget, sometimes because of space. But I've learned that, with meticulous work, most of the limiting factors that come up can actually become the starting point for a great idea - if you know what you're doing. Let's face it: in our profession, there is a long tradition of impressively overcrowded and spectacular stages. The less charismatic the actor, the bigger the fireworks needed to sell tickets. If you're doing a semi-staged performance, the actor cannot ever get bored, not even for a second. There may be a bench on stage instead of a church, there may be a table and two chairs instead of the office of the chief of police in Rome, but if the singers are strong enough characters, they will make the production a success. It works less well the other way round: in 'hyperactive' performances, distractions make it difficult for the audience to concentrate on the essence. - You are almost at home in Hungary. We know you well as a concert singer, conductor and opera singer. Have you ever wondered why the Hungarian public welcomes it with such love? - Hungarians are incredibly passionate! I remember my debut in Budapest in 2000 particularly well: the applause of the Hungarian audience has a special power. I dare say: a love story began there and then, and it has only grown stronger over the years. I remember most of my concerts in Hungary with fondness, but I am especially grateful for the world premiere of my Requiem Aeternam in 2022 at Müpa Budapest, where I had the opportunity to work with my future Desdemona, Klara Kolonits, alongside the excellent Hungarian musicians and choir. I have also made a film of the concert, which I hope will be shown on television once the bureaucratic hurdles have been cleared. Perhaps next year, on the quarter-century anniversary of my debut in Hungary?

|

|

Production Photos

|

Our Photos

|

A general statement of dismay: the lighting in this production was perhaps the worst we had ever experienced. The first half of the first act was almost impenetrable black; the second half of the first act was so bright as to make the singers into silhouettes. Lighting was a little bit better (not much) in Act II, but the stage was still mostly black with some spotlights that sometimes illuminated the singers and sometimes didn't, depending on how and where they stood. Sometimes the light was so bright that half a face was erased and the other half hidden in shadows; sometimes one of the singers was illuminated while the second (or third) standing right next to him was lost in shadow. The second half of Act III was the best for being able to see what was going on, probably because there were so many folks involved that the director realized that it would make no sense to have the majority of the singers obscured in blackness but Act IV brought back the light box that either bathed the singers in light so bright it burned out their figures or became so dark they were puppets in shadows. In addition, the light kept changing Kelvin temperatures, so sometimes the light was blue tinged, sometimes red tinged, sometimes green tinged, sometimes orange tinged, sometimes in the same scene. The lighting sometimes underexposed, sometimes overexposed. From our seats, it was frustrating and fatiguing trying to make sense out of a drama when the director so obviously went out of his way to make sure we couldn't actually see the details of it or the effort the actors were making to bring their characters to life The director's statement that layering a veneer of acting atop the music and lyrics robs the opera of its intrinsic nature seems even more bizarre when you see a demonstration of what he must mean: murky and murkier. Why bother with staging it at all if there is no value in the scenic, just the musical. If not providing all the key ingredients to an opera, why not just settle for a concert performance and spare the theater the expense of a stage setting at all? It didn't help that the director also decided he needed to have a mesh curtain covering the stage to further obscure vision: apparently, he was going for a dream-like concept where nothing is clear and nothing is for sure and everything is black and white, except when it isn't: his way of presenting the story seemed to be to smudge everything and leave it to the singing actors to do the best they could under dire circumstances. Folks sitting close the the stage undoubtedly had fewer problem seeing the action and lucky for them. From our seats in the balcony it was a struggle to maintain interest in the opera we love so much because of the strain of trying to experience a dramatic as well as auditory performance. We shouldn't have to choose.

|

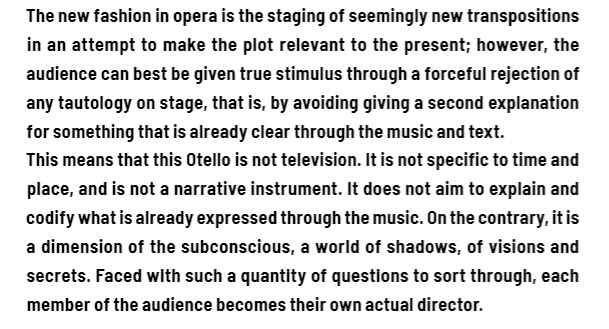

Statement of Concept

|

To which we say poppycock. Here's one reason it's a false narrative. One of the beautiful qualities of opera is that while it helps to understand the language in which the play is sung, it is often impossible to understand the singer during a performance. Reasons vary, from audience members not knowing the language the opera is sung in so they have no idea what the libretto says to non-native singers not getting the pronunciation quite right and finally to the need of singers to to sing vowels and consonant in a vocal way that often leads to some distortion that keep the words from being easily understood. Titling systems help but they are a relatively new addition to the theater and some find them a distraction. Insisting that the audience should know what is going on because it is clear through the text which they don't know and which is being performed by singers who may not be precise is strange, indeed, yet there on rests one of the director's primary arguments for his approach to this production. We don't need to have singing actors interpreting the words we may not understand; the 'subconscious' should do that for. Shadow figures and secrets known only to the director are the way to go. Each member of the audience will of course take away thoughts and feelings about a production but it shouldn't be on the audience to interpret the intentions the director or make sense of nonsense. Or to sort through the dross on the stage to create a secondary performance by picking up the pieces left by an incoherent director. And if you want me to become the actual director, the give me access the lighting board so some illumination can be added to a very dark situation.

|

|

Our Photos -- Act I Act I was VERY dark and was sometimes blue and sometimes yellow and sometimes white.

Act II

Act III

Act IV (sorry)

|

Curtain Call Photos

|

|

Backstage

|

|

Last Updated: Monday, December 23, 2024 © Copyright: Kira