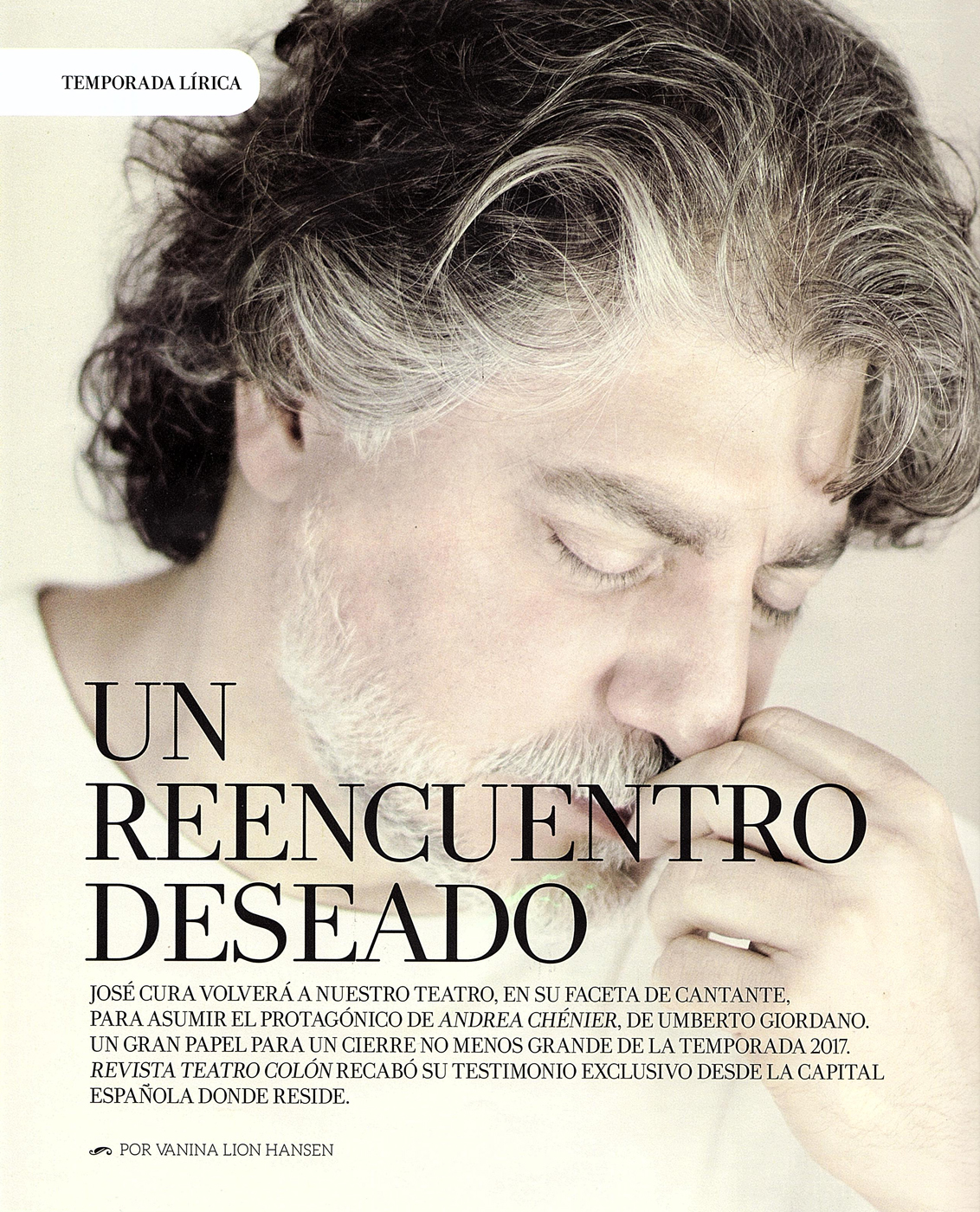

Balance. José Cura opined that

the past must be respected without it

becoming "necrophilia."

"When the prize is at home, the

weight and responsibility are

different," stated the Rosarian tenor,

composer and director José Cura shortly

before receiving the title of Honorary

Professor from the National University

of Rosario. Settled for almost twenty

years in Madrid and visiting his

hometown where he had already been

declared an Illustrious Citizen, Cura

chatted with Escenario about his career,

his projects and his work in some of the

most prestigious theaters in the world.

Friendly and in a good mood, he said

that classic art may please or not, but

it requires "time" to enjoy something

more than "the little song of every day"

and that his style is characterized by

"sincerity" and by trying satisfy

neither "conservatives" nor "the new."

In a broad sense, he opted for a society

in which "the love for the past, which

must exist, does not turn into

necrophilia, because then it is a

defect, and the triumph of the new does

not become a mockery of the past,

because it is an error."

Q: You’re an Illustrious Citizen

and now Honorary Professor. What do

these distinctions mean to you?

José Cura: And the next mayor

(laughs) The prize and the applause or

recognition most difficult to achieve is

always that of your brothers, that of

your family. That has a double cut, the

pleasure of feeling recognized and

respected by your brothers and the

commitment.

Q: How did you live in Rosario

the first stage of your career? What

projections did you do then?

JC: I believe that all young

people, and I do not say it in the

chronological sense, but include those

who remain young at 80 because they live

with projects in their heads, we have

and we drag the eternal dream. You

finish one and another comes and

another. But the arrival is almost less

important than the journey. It's all

good, but when you start everything is

like a romantic idealism. Then there

comes a time, after 50, and your

idealism stops being romantic and you

become more stoic and you play for

something that is worth playing. That

is the difference, but idealism is only

changing its face.

Q: What is your assessment of

the changes and transformations?

JC: The crises serve to help you

grow if you know how to capitalize or to

sink you if you let them drag you down.

Obviously each generation has to fight

with their own things, but until the

2000 and peak changed more than anything

the modes with which we fought but the

tools were basically the same. From the

overwhelming force of technology that

almost manages our lives, we had to

learn a completely different set of

codes. Some are very good and others are

dangerous. One of today's delicate

risks with technology is that it can

make you famous, something that was once

part of a huge process and it happened

if you really had something to tell.

It’s relatively simple if you know how

to manage a means of communication or

networks. Now, because being famous has

become easy, the difficult thing is not

to be famous but to be great, worthy of

fame.

Q: Technology also invaded all

areas, including music ...

JC: It happens in newspapers

especially ... Being able to take

advantage of some of this for the

distribution of music so that it reaches

further and to more people would be a

positive thing, although the negative

for the industry is that at the business

level of culture, there were

transformations to the industries.

Where before a hundred people were

needed to put a record on the street now

you need one who presses a button.

However, the artistic creators are still

the same, the singers, the orchestra,

except in electronic music. But the

amount of people needed for that product

to reach people is a thousand times

lower and that creates a huge crisis at

work in our industry.

Q: Why did you choose lyrical

singing or not rock or another genre?

JC: My training is as a composer

and orchestra conductor, that's what I

studied at the School of Music. The

vocals came a little later. Singing was

a complementary subject at school and

through that subject I discovered that I

had certain aptitudes beyond singing in

a choir. But even now more than before,

I continue to develop orchestral

composition and direction. Being a

famous tenor helps people have some

curiosity, now if it's a good or bad

work or a piece of crap, however famous

you are will continue to be, but at

least opens a door (laughs).

Q: Does opera still have

validity?

JC: I always answer that with

feet of lead. The changes and the

innovations at first helped and then we

will see where we are going to stop.

What scares me the most is the path the

world is taking in climate, energy and

war. I am not one of those who say that

the past is always better, but I think

that we must continue with some things

in classical art, with everything that

has to do with beauty and that keeps man

with his feet on the ground. But you

also have to be careful that by having

the most beautiful picture, you have a

wall to put the painting on. That is to

say, go on with everything but don’t

forget the essential thing because we

are going to have classic opera but we

are not going to have a world.

Q: What kind of opera could

represent the current complexity of the

world, not only with the climate crisis,

but also with religious extremism or

extreme political tensions?

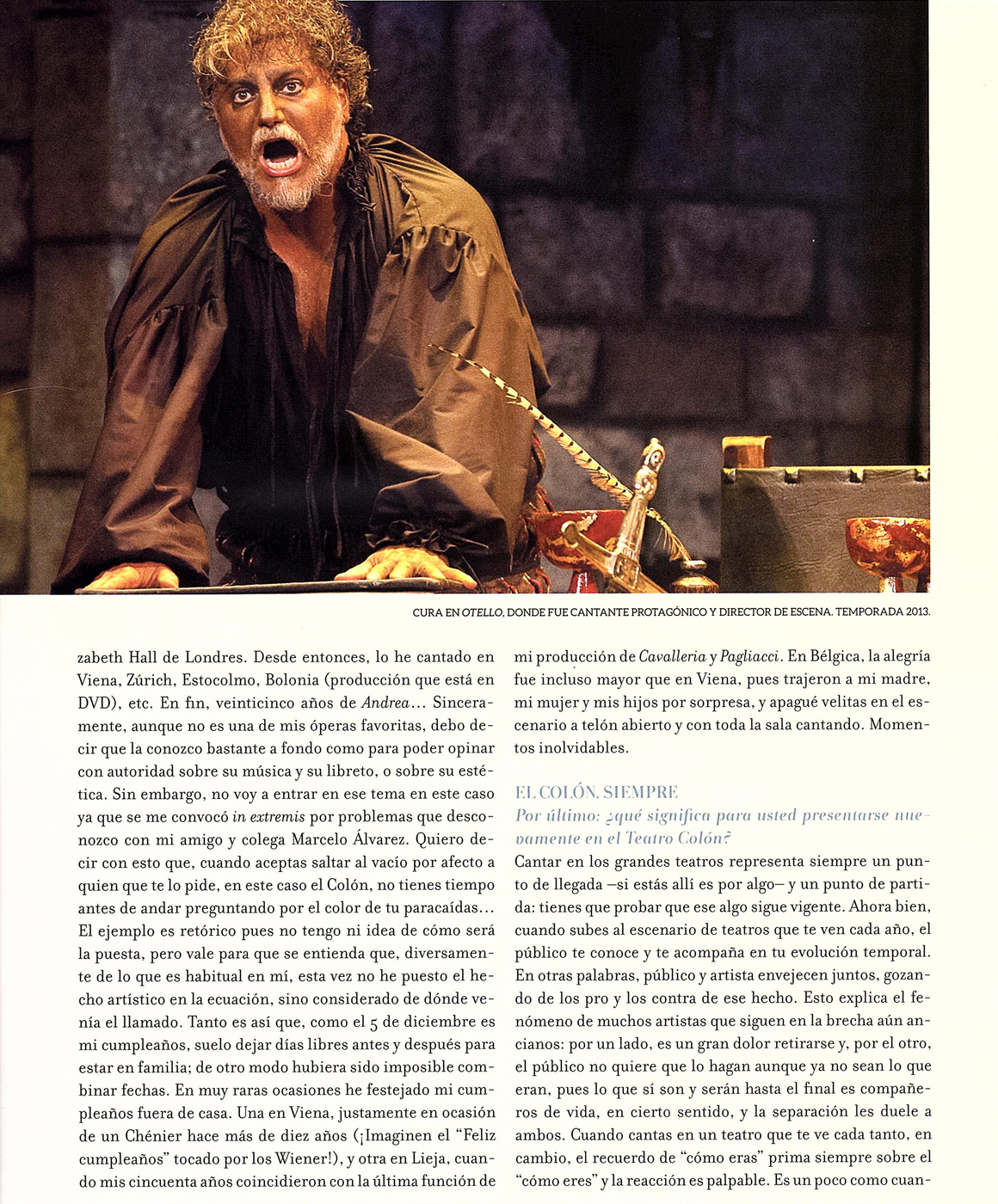

JC: The background of art closet

in general has been to pull from and

even were premonitory, or originally was

taken from scandal that today are

something ordinary. For example, the

gender violence that was already

denounced by Shakespeare with "Otello"

500 years ago.

Q: In what way did these

historical, political and social events

influence the emergence of other genres

such as jazz, rock, blues?

JC: I'll say it in a culinary

way: there is leaven and there is yeast

and when there is yeast the dough

grows. From that you can draw all the

analogies that come to you. Whenever

there are crises, things happen and in

crises the opportunists are mixed, with

the idealists, the dreamers, the

dishonest. We are all mixed up and will

depend on what type of individual there

is in the majority where everything is

headed.

Q: How do you live in the

interpretation of the opera the fact

that not hitting a half tone can

generate a conflict or affect an entire

production, something that does not

create scandalize other genres?

JC: It is a conflict that for me

is positive. The world is divided

between conservatives and progressives,

in broad strokes. There are those who

believe everything in the past was

better and everything present is better

until it smells a lot tomorrow, and then

those who say "we can do something

new." I think both forces have to live

together and it is good that they live

together. When everything is

conservative we stay in the Paleolithic,

but when everything is progress we lose

roots. It is the balance between the

two that makes a good society. But

society is made by men and not by

machines, then it adds an ingredient

that is passion, more or less heat,

defend ideas with more or less

vehemence, and man is man because it is

so. One thing is that they fight with

each other passionately with an idea of

wanting to do a good, and another is

that if we coexist with that we do not

feel sunk by the fight but we feel

stimulated because for me it's great

that a guy wants to pull forward as

someone else wants to balance. I never

thought that a very serious issue. The

only thing that seems sad, but is also

part of the nature of man, is when they

want to be right, they start insulting

or mistreating. In that sense today

more damage is done than before because

we have the great alibi that gives us

anonymity. Today we can shoot like

snipers without anyone knowing who we

are. That complicates the situation

because it has transformed an old issue

like the world into an act of cowardice

that hurts, and that does not work.

Q: How would you define your

style?

JC: My style has always been

characterized by sincerity. When I do

something, I truly believe in what I am

doing. I do not make it old so that the

conservatives are happy nor do I make it

modern for the rest. I do it as my

sincerity tells me that I have to do it

and then conclusions will be drawn.

When you see a show, whether I wrote it,

directed it or sang it, what you will

see is something that I truly believe in

it. I think the basis of success is

also that because people can argue if

Aida arrives on a motorcycle or on a

camel, they are details and a discussion

until tender, what is serious is when it

arrives in one thing or another, what is

seen betrays the lack of conviction of

the creator. There everything goes to

the devil. The progressive is so

negative that he progresses only because

he does not like anything that looks

like the conservative who keeps doing it

only for fear that nothing will destroy

what has already been done. Both things

are negative. I believe that sincerity

is the most important word. And the key

word is originality. Originality is a

great word because it speaks of origin,

sources, birth, root, but also has a

connotation of the future, is something

original, new. In the same word in

which both conservative and progressive

can exist. And if they can coexist in a

word why won’t they be able to coexist

in society? A society in which the love

for the past, which has to exist, does

not turn into necrophilia because then

it is a defect. And the triumph of the

new does not become a mockery of the

past because it is a mistake. This

applies to all behaviors of the human

being, from the technological, to the

artistic, family.

Q: Was the public of the opera

renewed?

JC: The public in general, not

only the opera fans, understood as that

part of society that consumes what the

entertainment industry proposes. People

sometimes confuse art with the business

of art, or sport with the business of

sport; they are different things. If the

money in football ends tomorrow, it does

not mean that the sport is over. People

can continue to play sports. What will

not be there is soccer spectacle in

which millions and millions are made.

And if the money for art is over,

because sometimes people say that the

crisis will end the culture, I say that

the crisis will not end with the

culture. If you want culture, the

libraries are there, the museums, the

academies, the schools are there. What

is going to end is the art trades if

there is no money. This has to be very

clear because if everything is not very

black and very ugly and you can not mix

things. In a world like ours, it is an

ever greater challenge to maintain

interest in a human activity that binds

us in some way to the past but

positively. Classical music, ballet,

like sports, are activities of human

beings and of culture. The Greeks

already said that sport was included in

culture. If we stop having an audience,

there is no need for culture. But while

there is an audience there is a product.

Q: Has the public moved away from

classical art?

JC: It is always spoken and we

fill our mouths because people will not

see classical music because it is

expensive, because it is only for the

elite. And that's a big lie like a

house. It is much more expensive to go

to see a Real Madrid match with

Barcelona than a show at La Scala in

Milan. Today we go to the Vienna Opera,

we are going to talk about the outside

because we like so much to look at the

outside, here we have the Colón, but you

can go to the Vienna theater for 16

euros, and the last minute tickets,

There are some for two euros. Just as

the artists or those who run the

business have to call things by their

name, so the public has to do it and say

I do not consume classical art because I

do not like it, it bores me or I do not

understand it. And he has every right.

No, you like other things. One thing

you learn over the years and stop being

so desperately passionate is to give

Caesar what is Caesar's. That's the

theme and not "I do not go to the

theater because it's expensive."

Classic art costs dearly because it has

a march more than the little song of

every day. And that implies more of an

effort than eating something in a rush.

The audience of classical art able to

understand that to enjoy all the wonder

that a great book, a great painting, a

great symphony, it takes its time. That

investment of time in a world where

everything goes so fast the classic art

is more that the last moment. The

validity of something that was done 200

years ago requires getting in, getting

dirty, perspiring. And that's what

costs the most. When we talk about the

fact that the public is moving away from

classical art, it does not do so because

it has less desire for beauty, which has

less and less time, because it does not

have it or because it does not want to

do it.

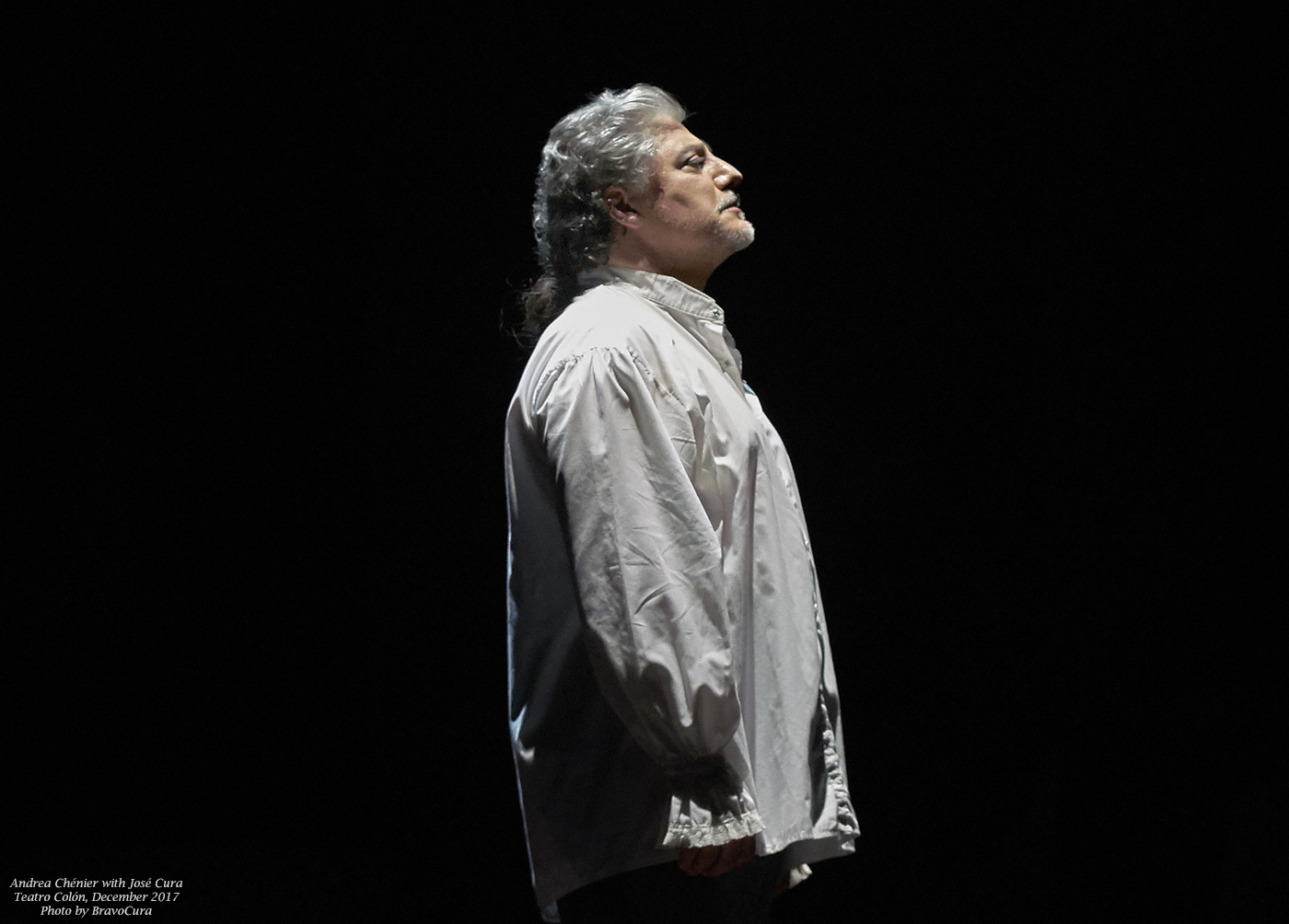

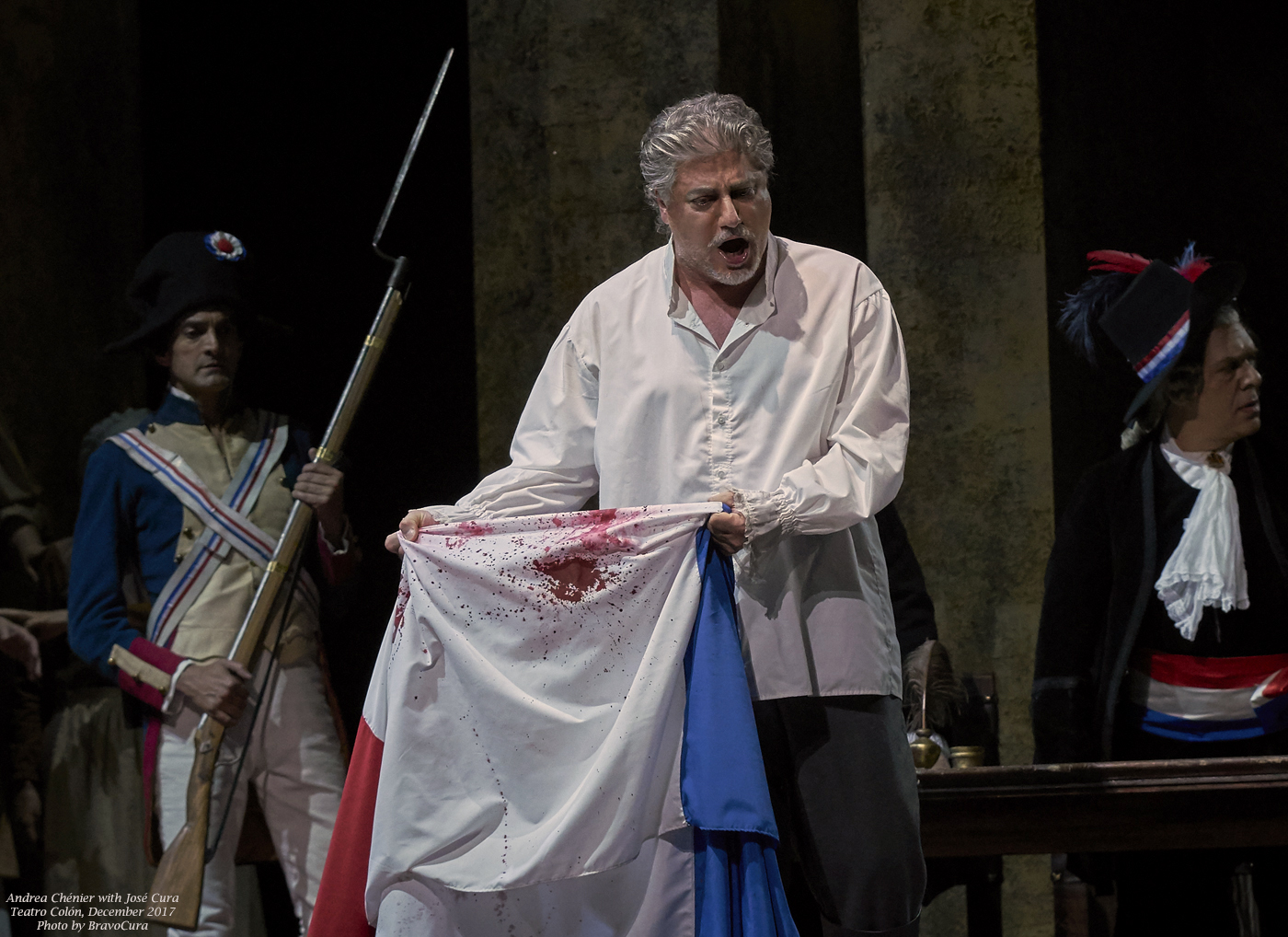

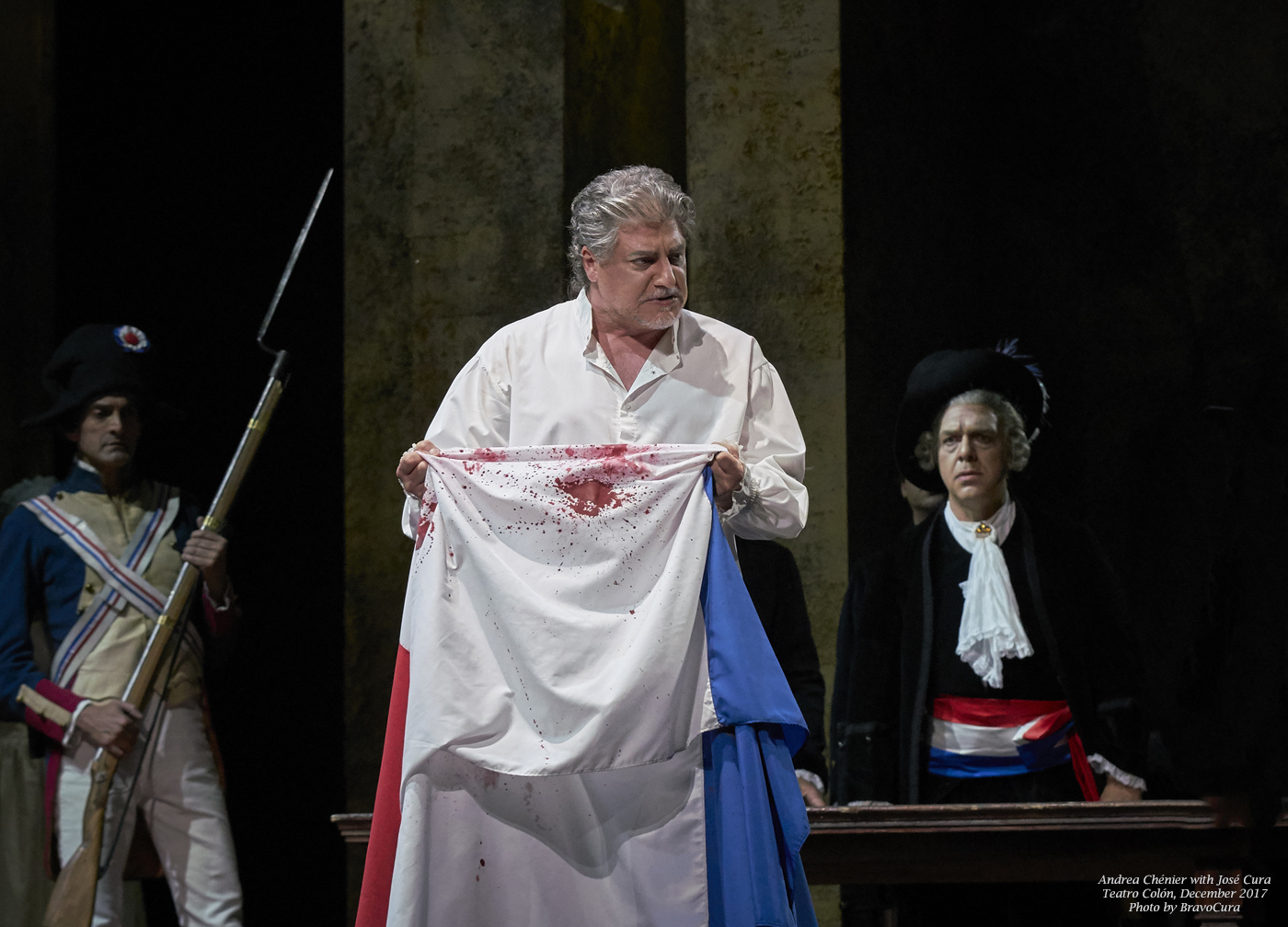

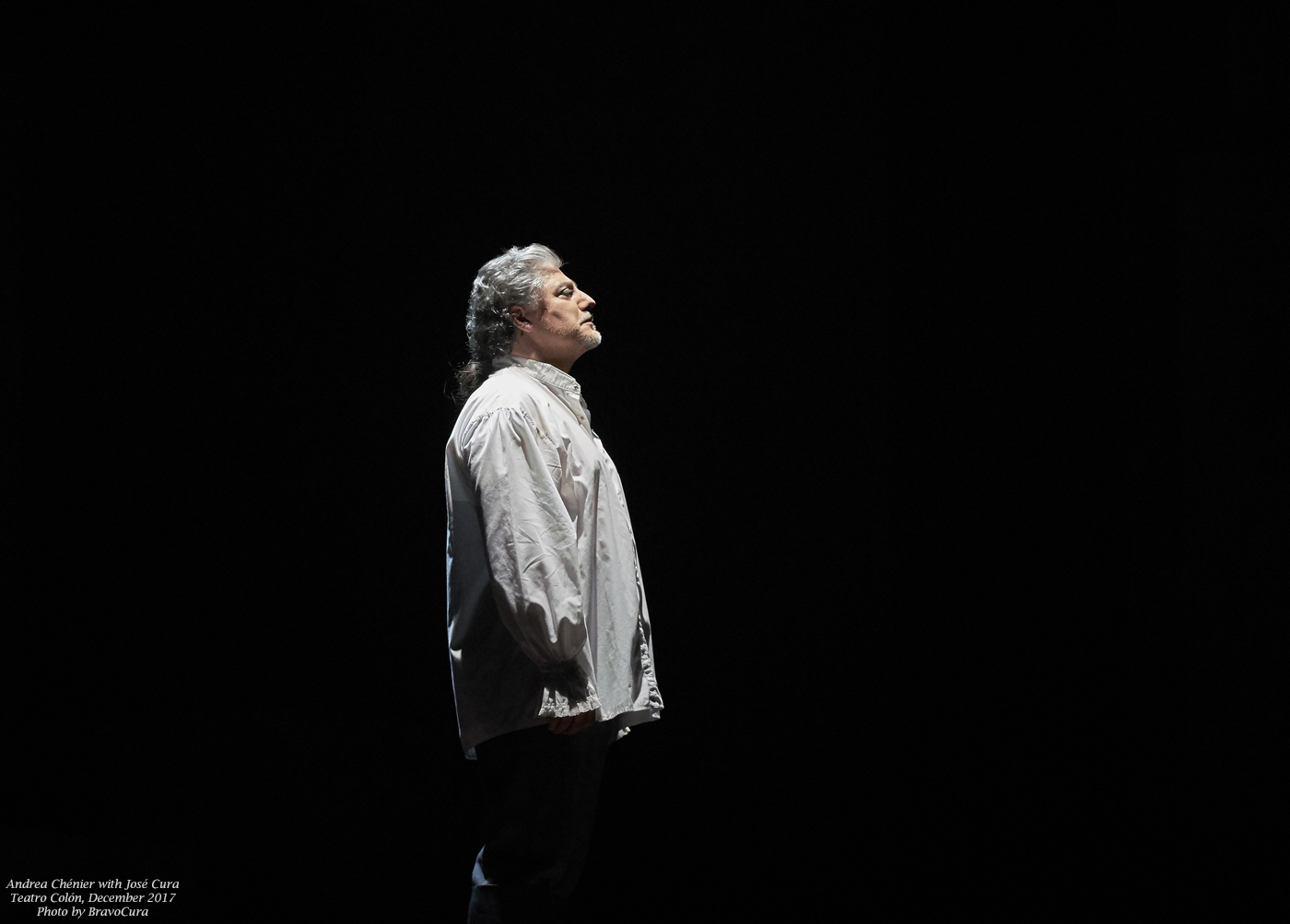

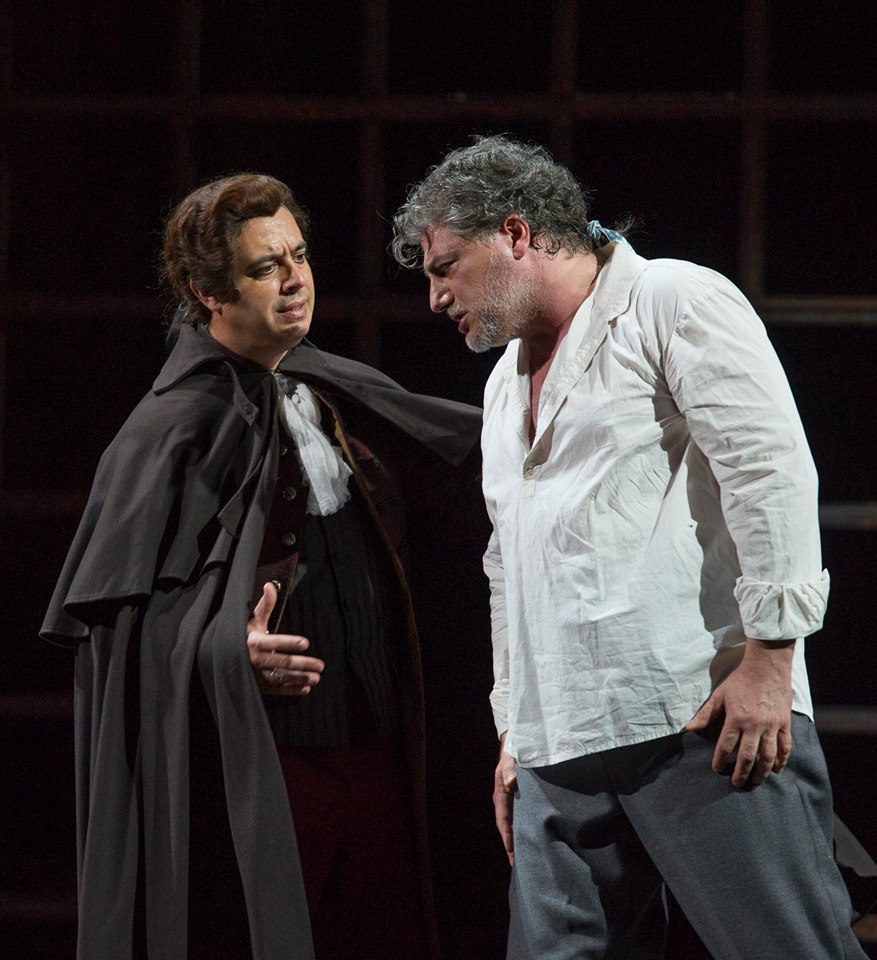

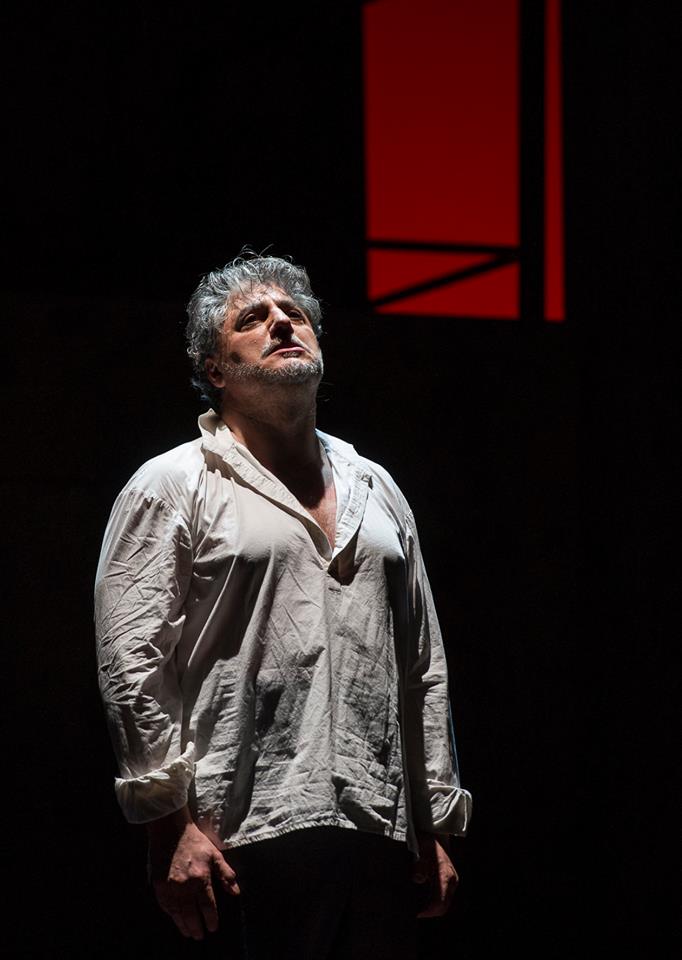

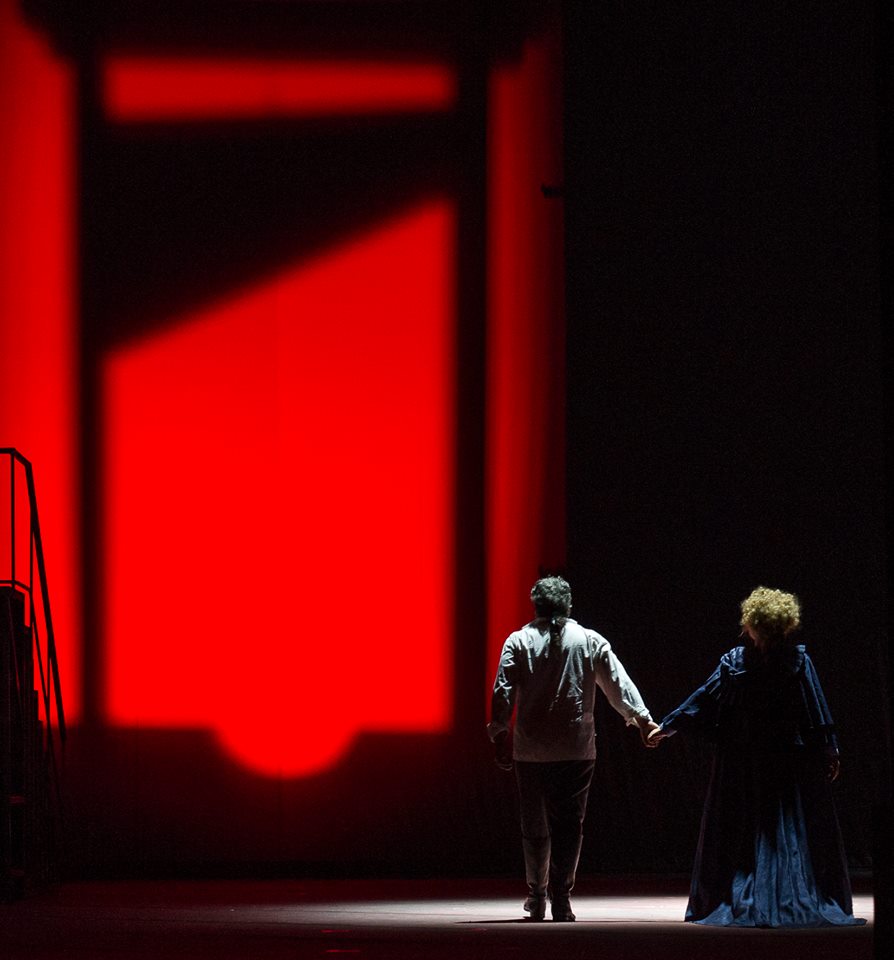

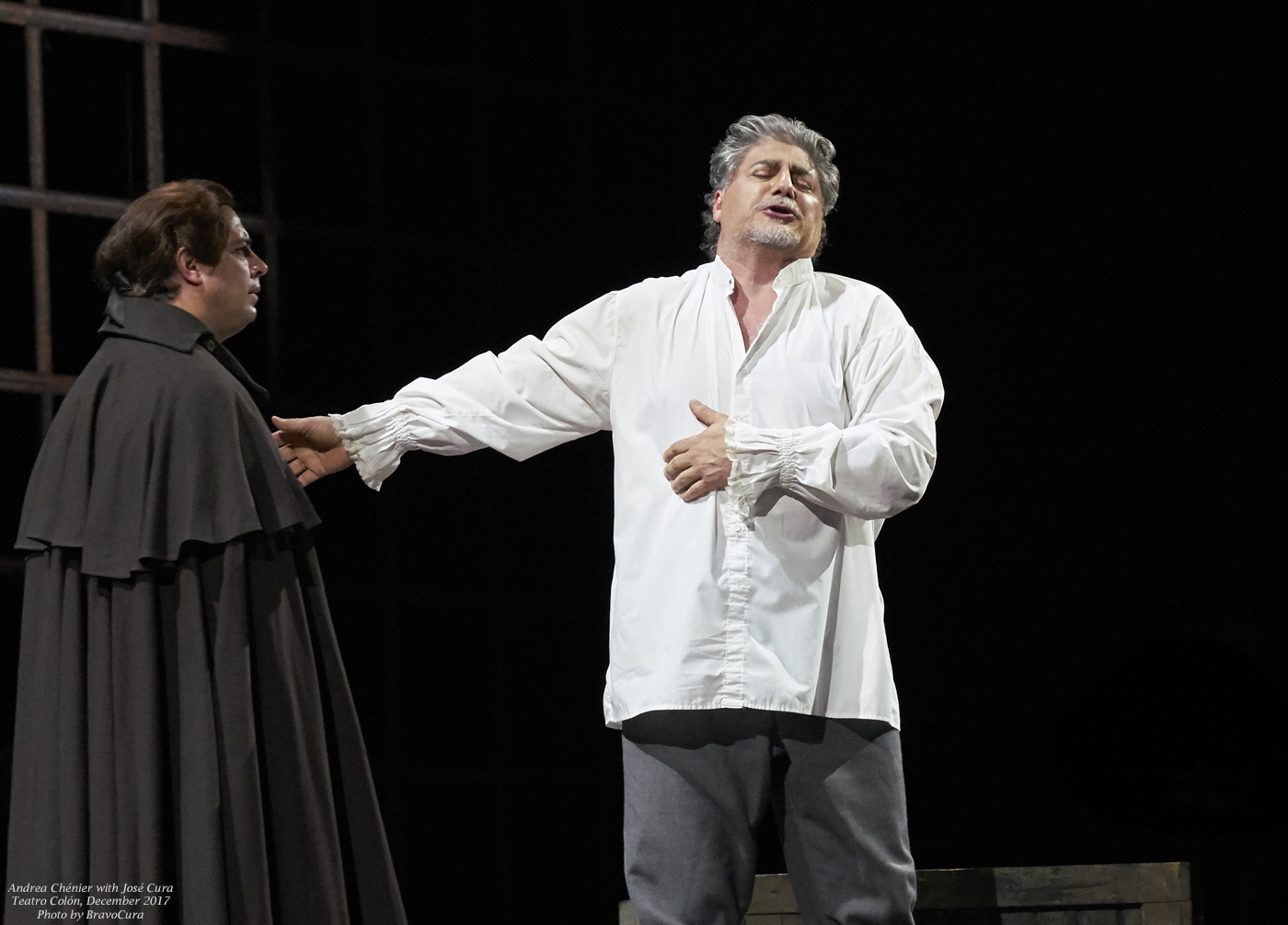

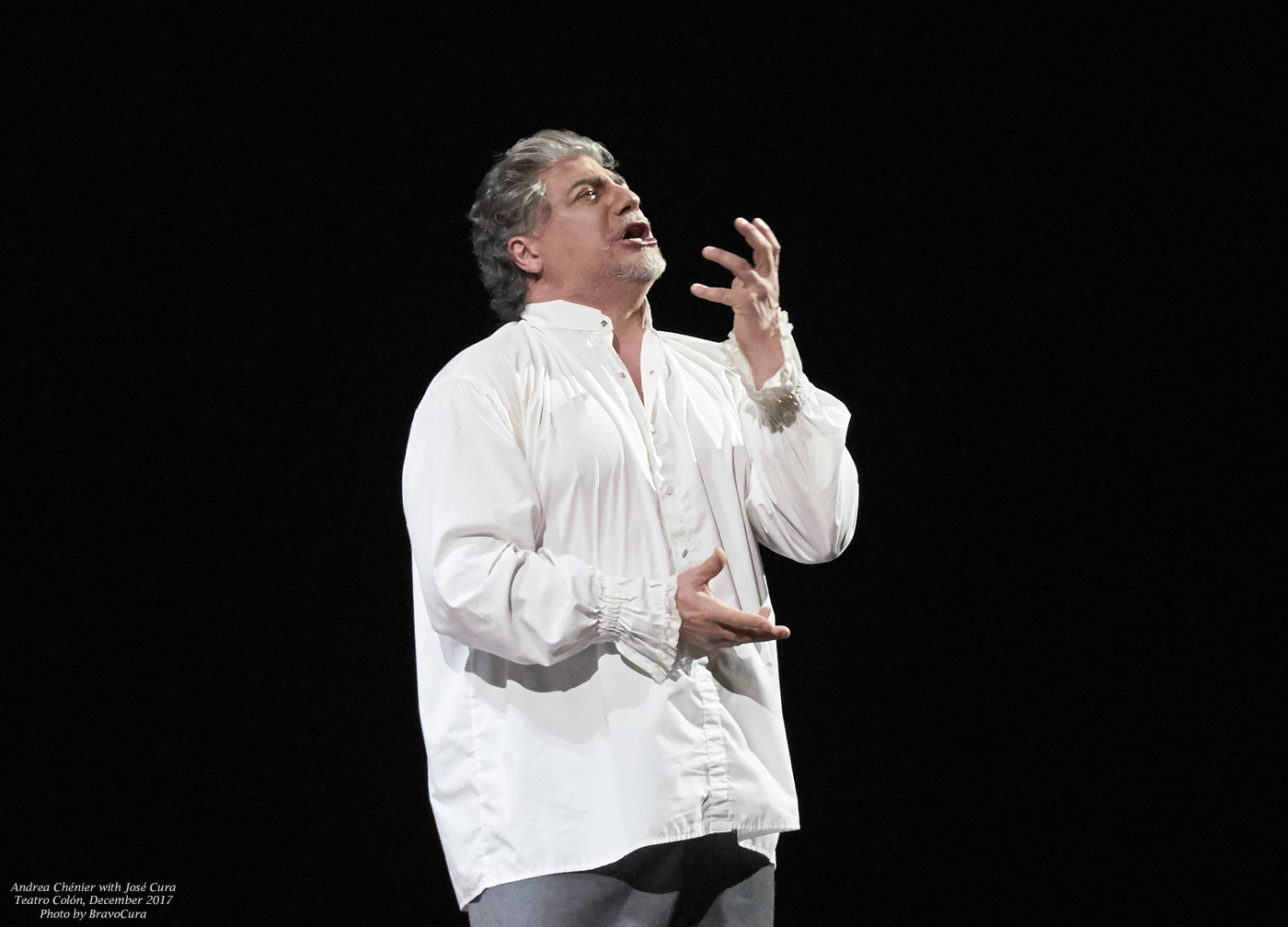

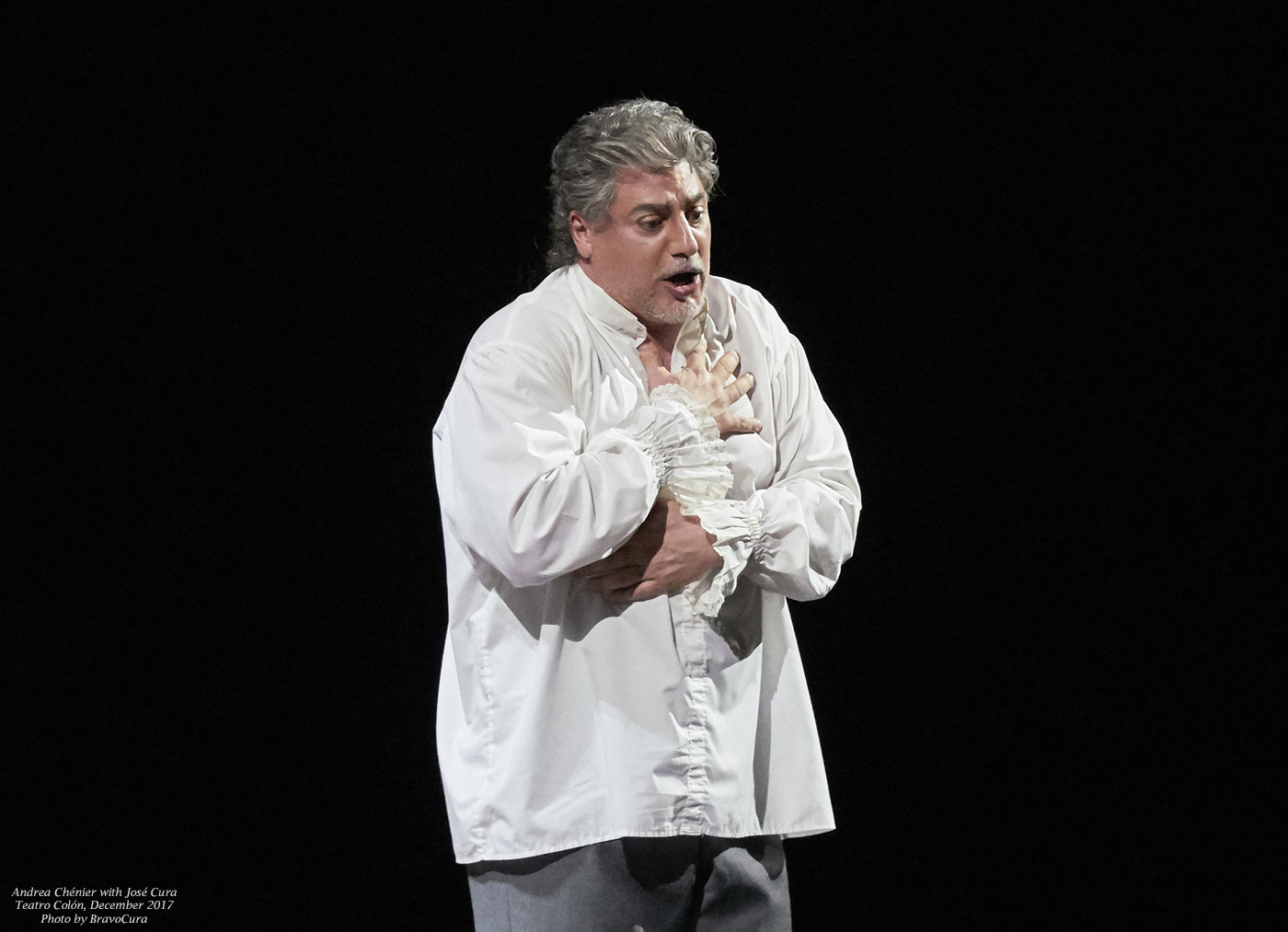

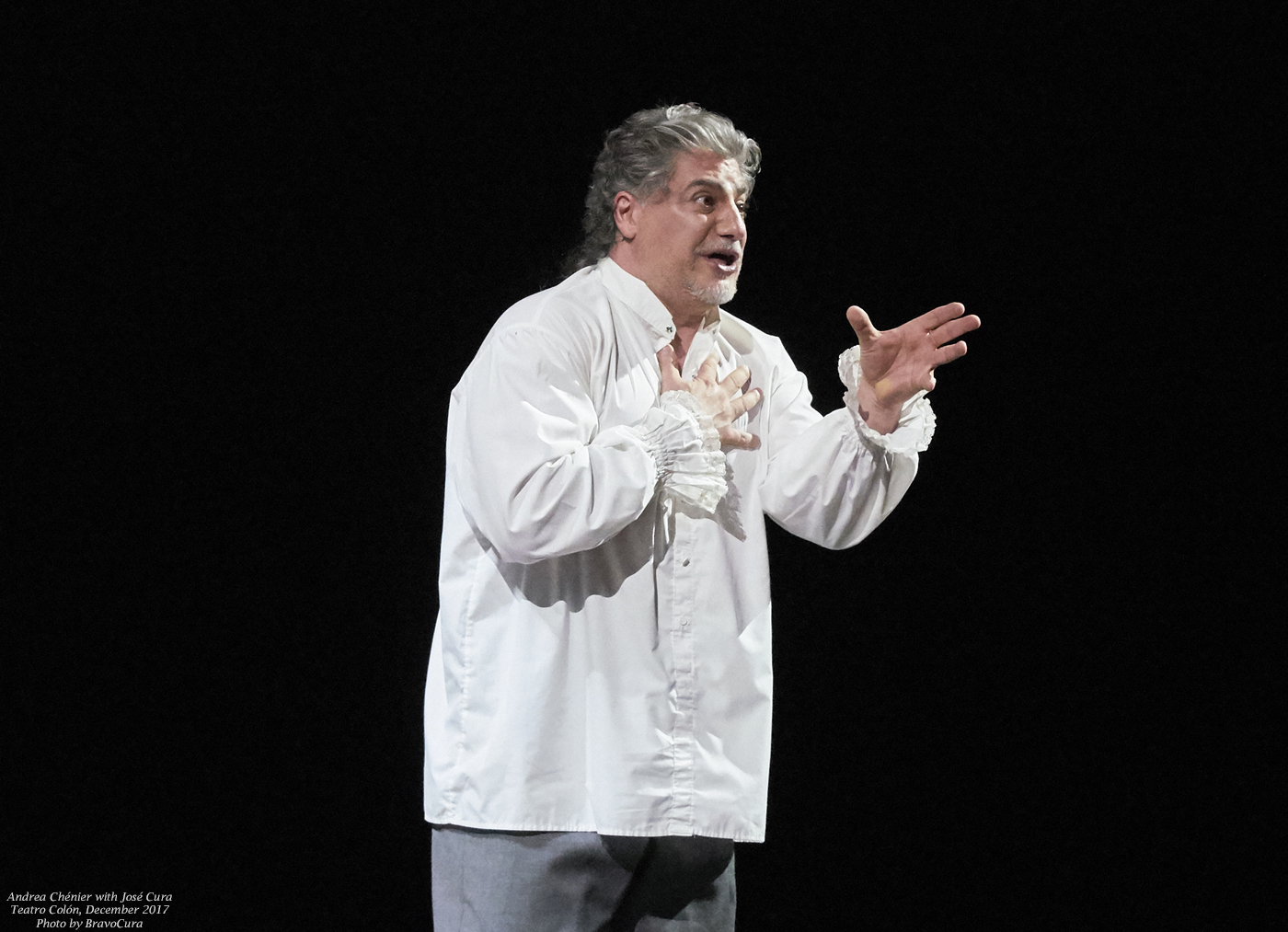

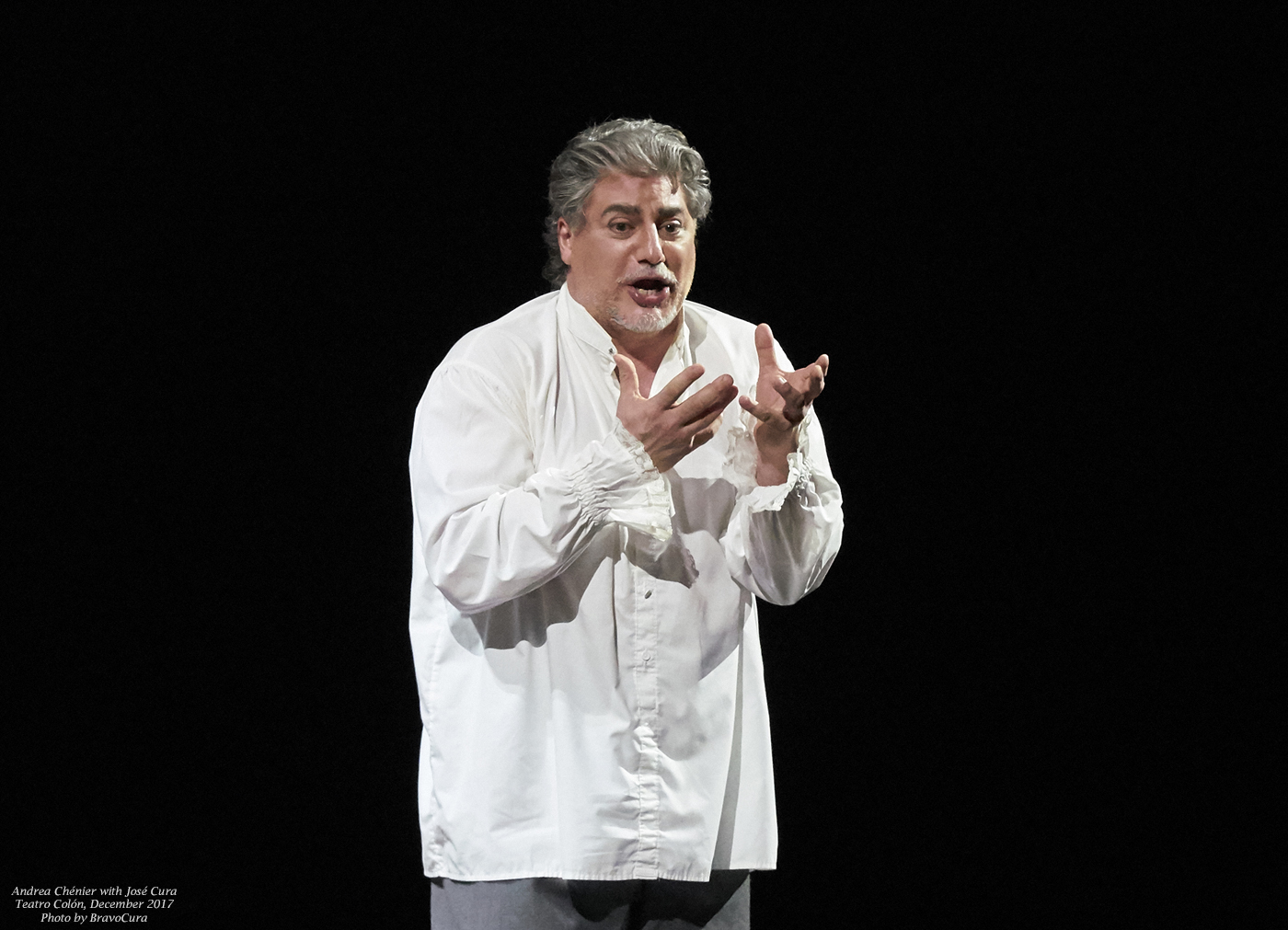

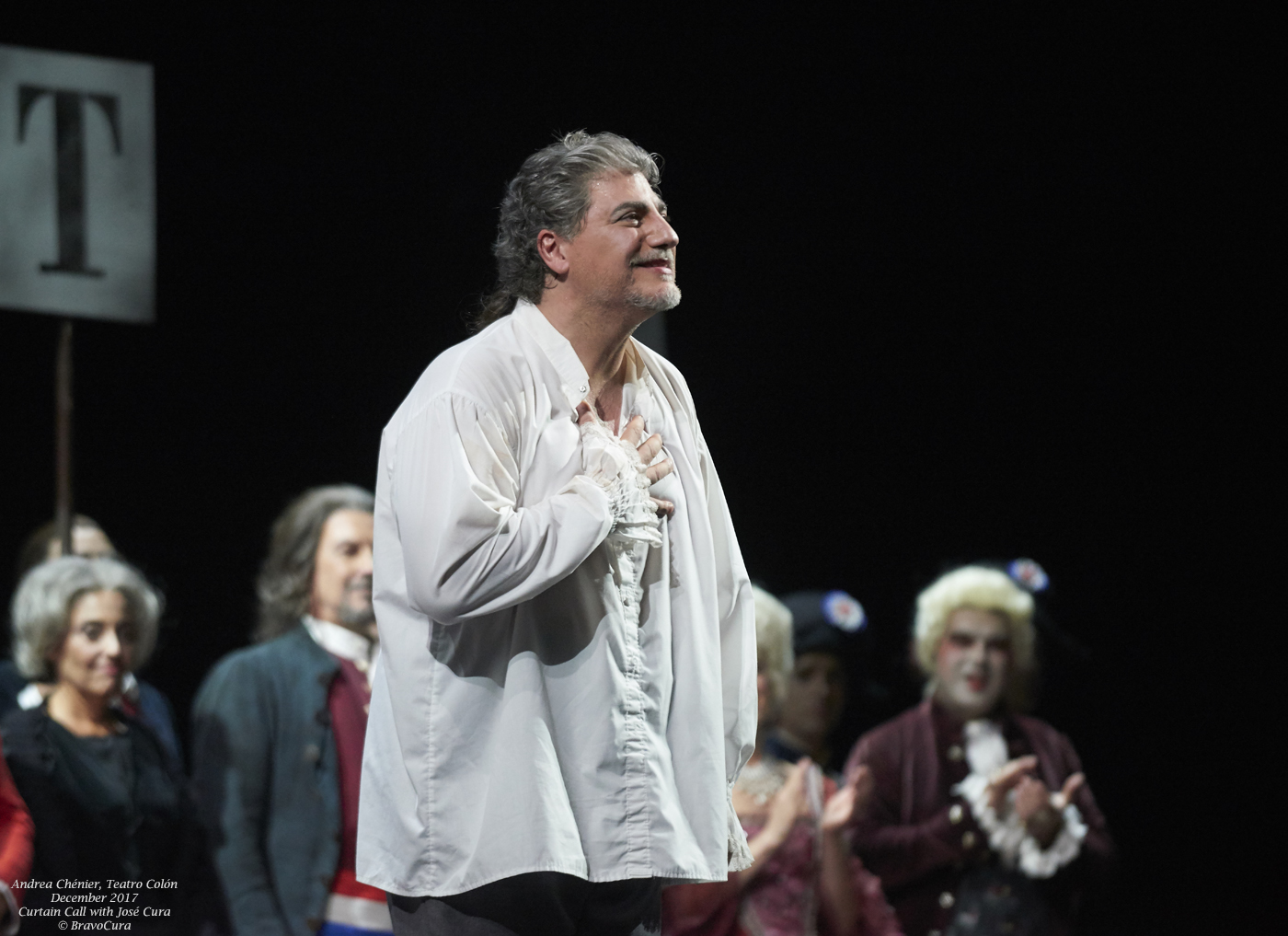

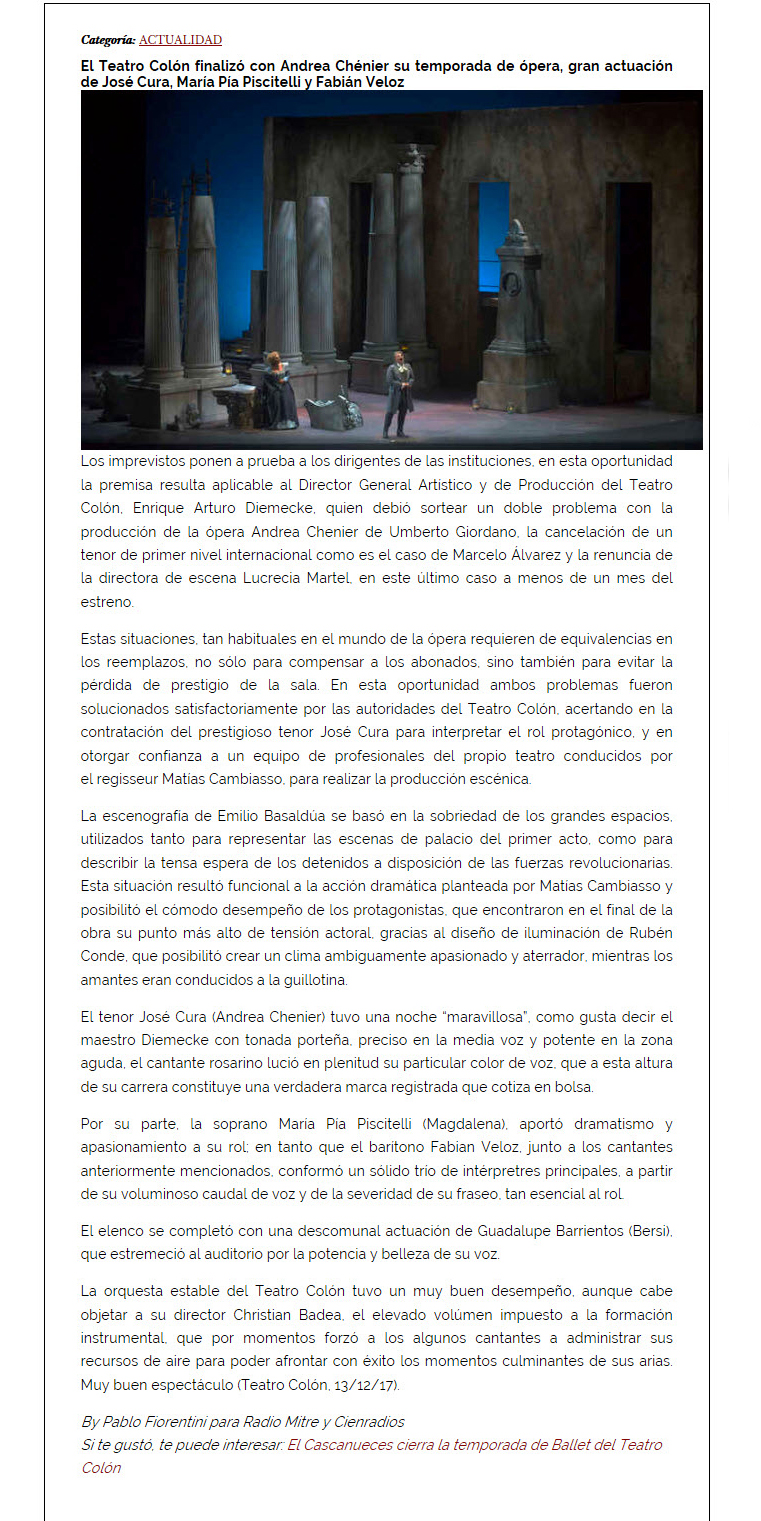

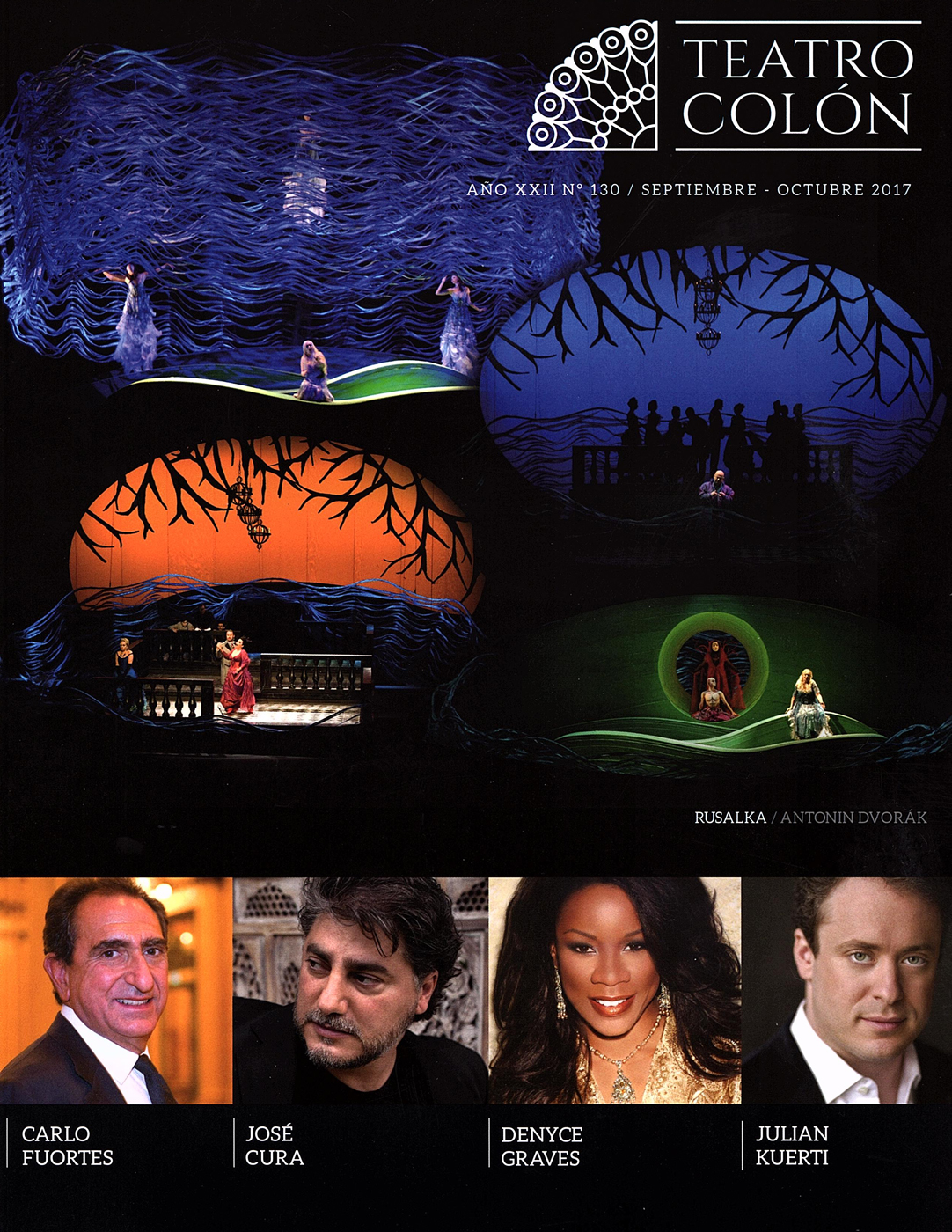

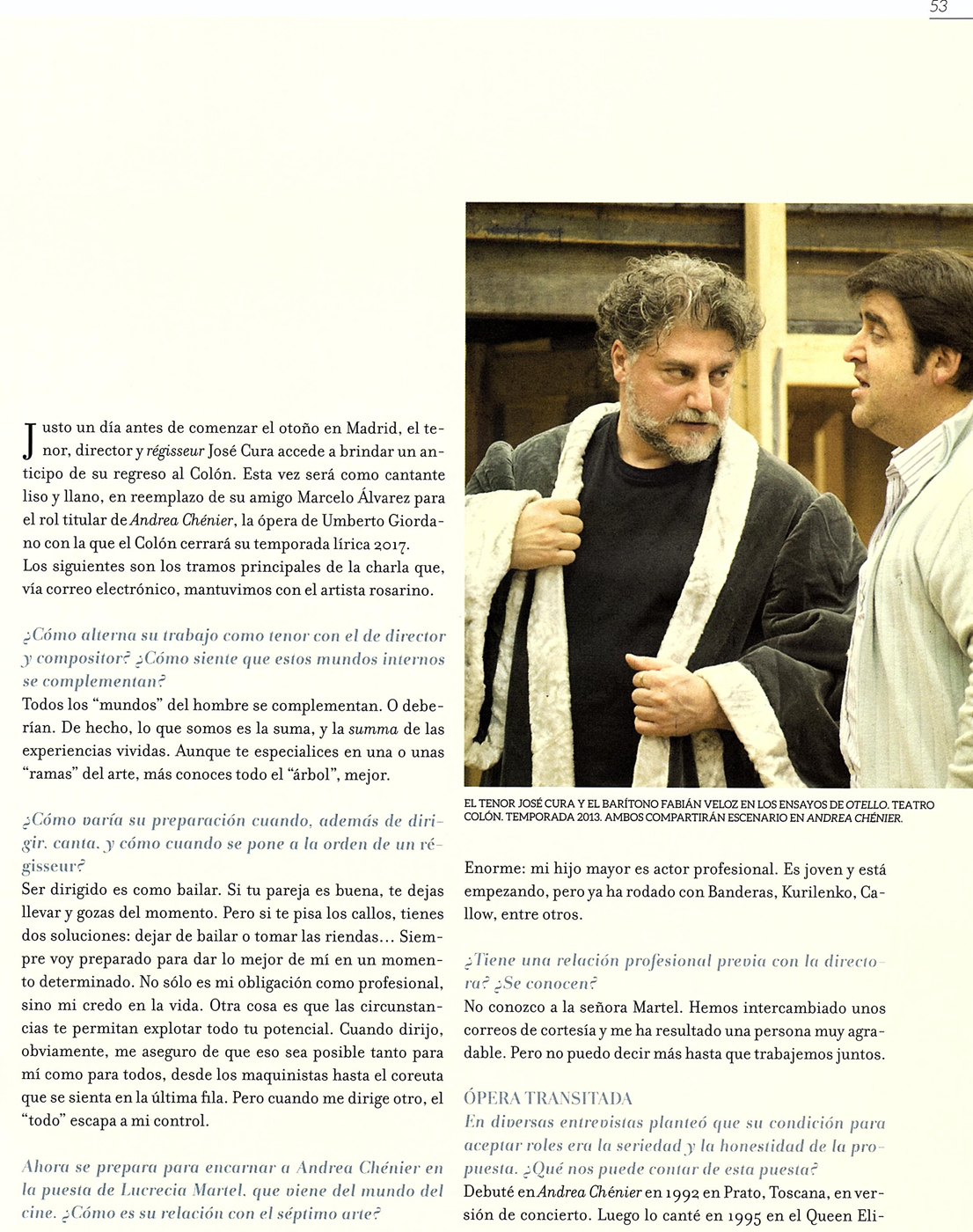

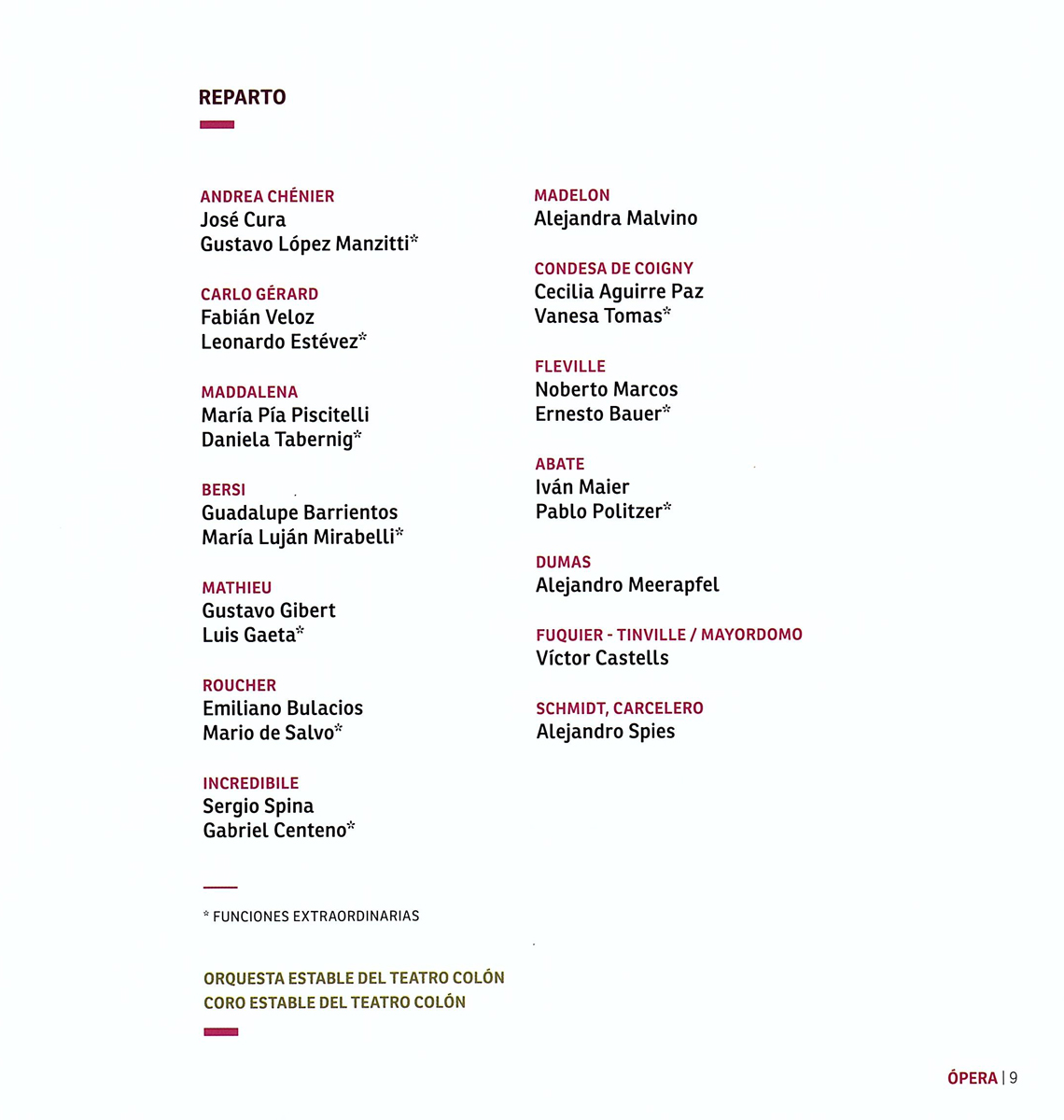

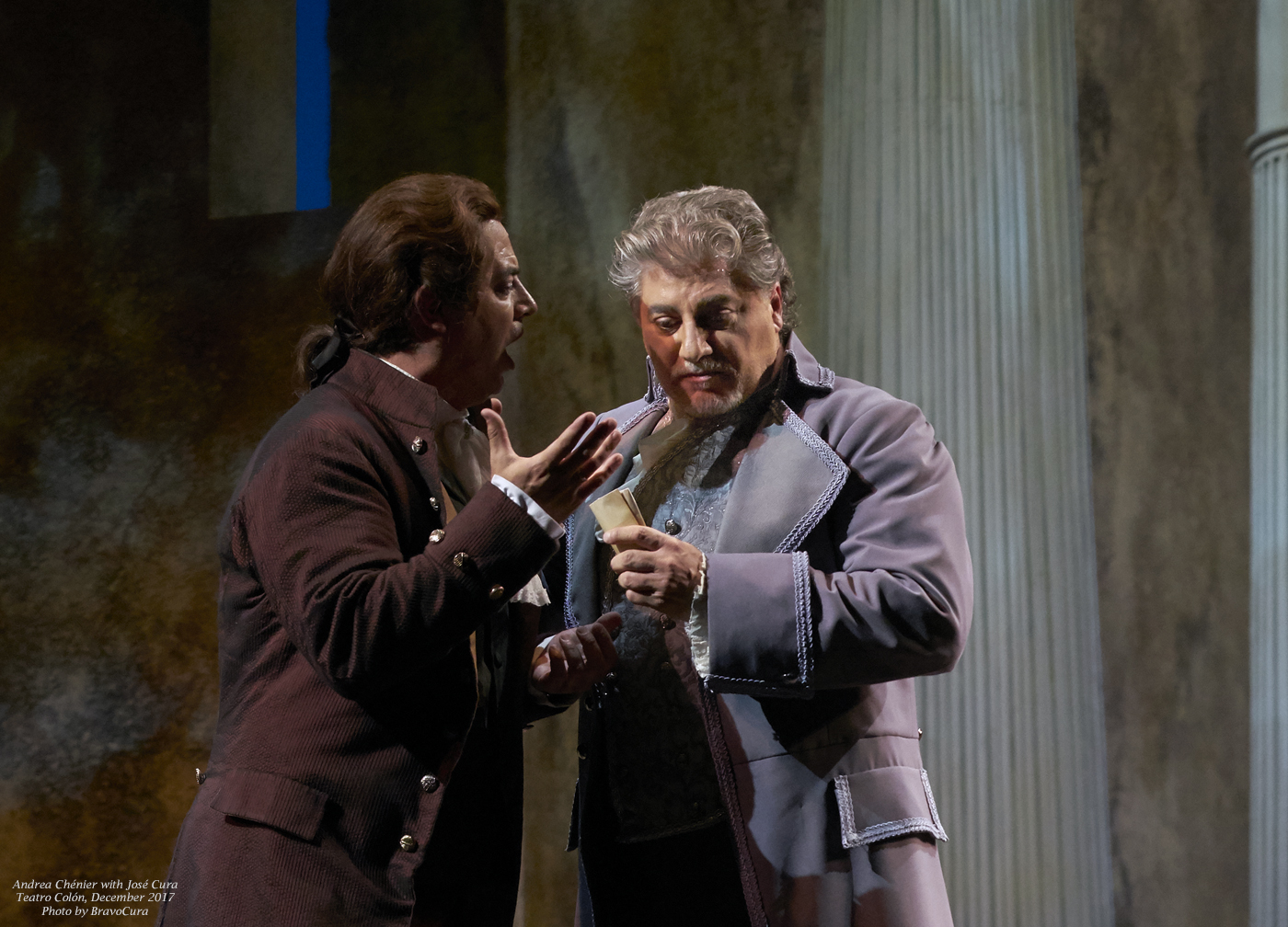

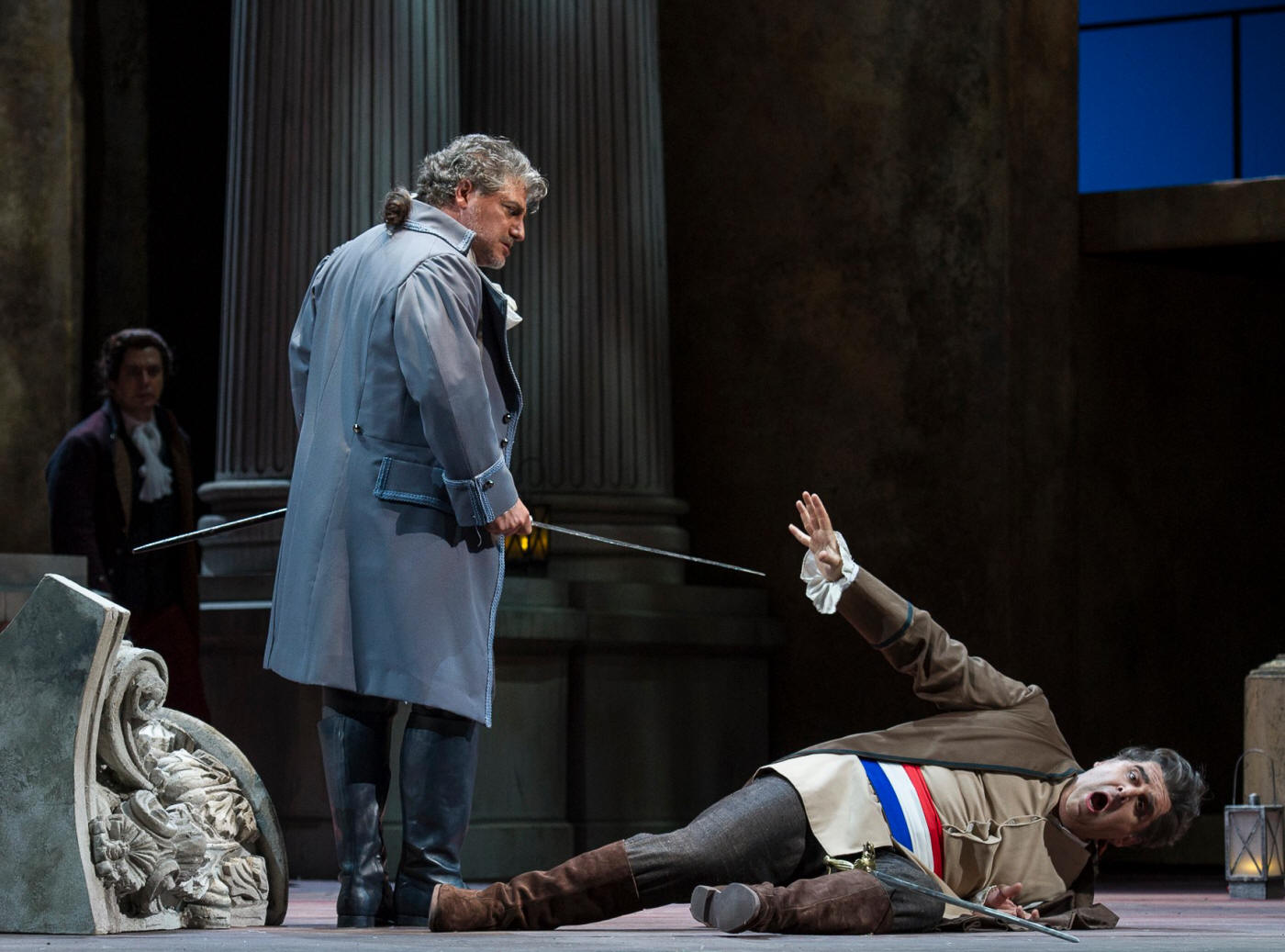

"Andrea Chénier" in the Colón

In this return to Argentina, José

Cura will star in the Teatro Colón the

opera "Andrea Chénier" based on the life

of a poet linked to the French

Revolution. The singer said that this

period is an example of how artists can

be protagonists in their time. "If

there was a revolution that was the

example of how far you can get supported

by artists, because if they are not

revolutionaries are those who warn of

potential dangers with their films,

books or music, this is it." Chénier was

on the side of the Revolution with his

writings, but when he saw that the

Revolution was beginning to have a

dangerous similarity with what was

revealed, he also denounced it, and

those who ended up cutting his head were

his own friends, "he explained about

this work he has already done in London

, Vienna, Bologna, Japan and Barcelona.

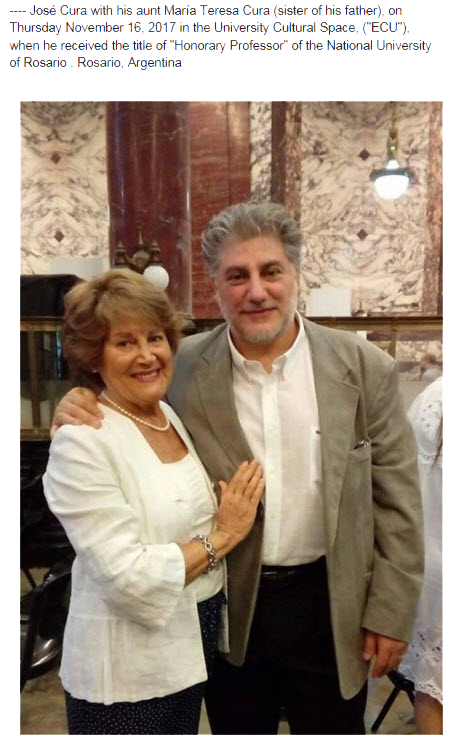

The "commitment" of a distinction

"A fortnight ago they gave me the

Onegin in Russia, which is like the

Russian Oscar in music, but when the

prize is at home, the weight and

responsibility are different," said José

Cura about the distinction given to him

by the UNR. Cura, who has added

international recognition throughout his

almost thirty-year career, added:

"Abroad has the character of honor and

satisfaction for the duty fulfilled, but

when it is at home a great

responsibility is attached. And the

applause or recognition most difficult

to achieve is always that of your

brothers, that of your family, that has

a double cut, the pleasure of feeling

recognized and respected by your

brothers and the commitment.” Cura has

also been named Knight of the Order of

the Cedar of Lebanon, Guest Professor of

the Royal Academy of Music, honorary

vice president of the Youth Opera in

London, among other titles.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)