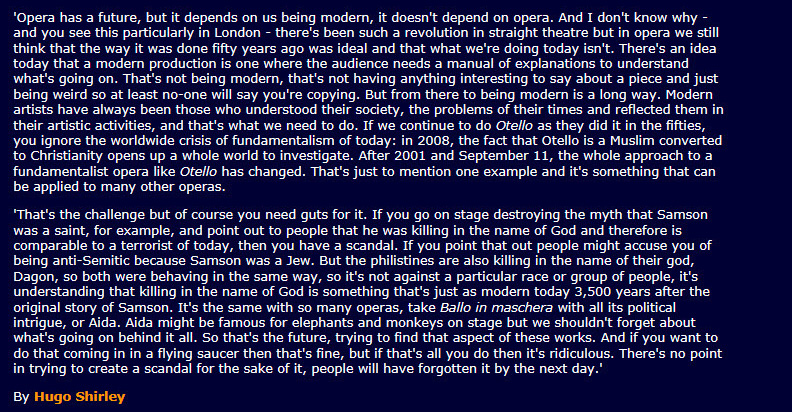

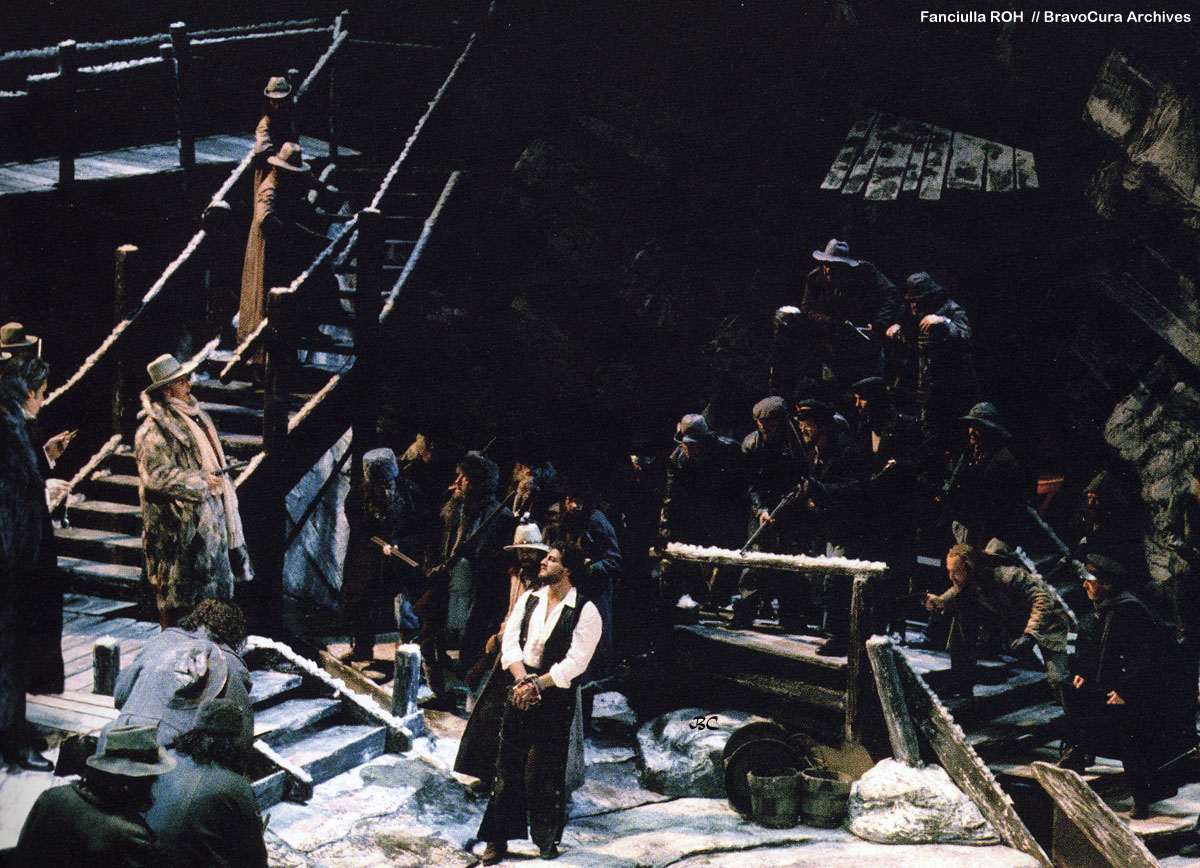

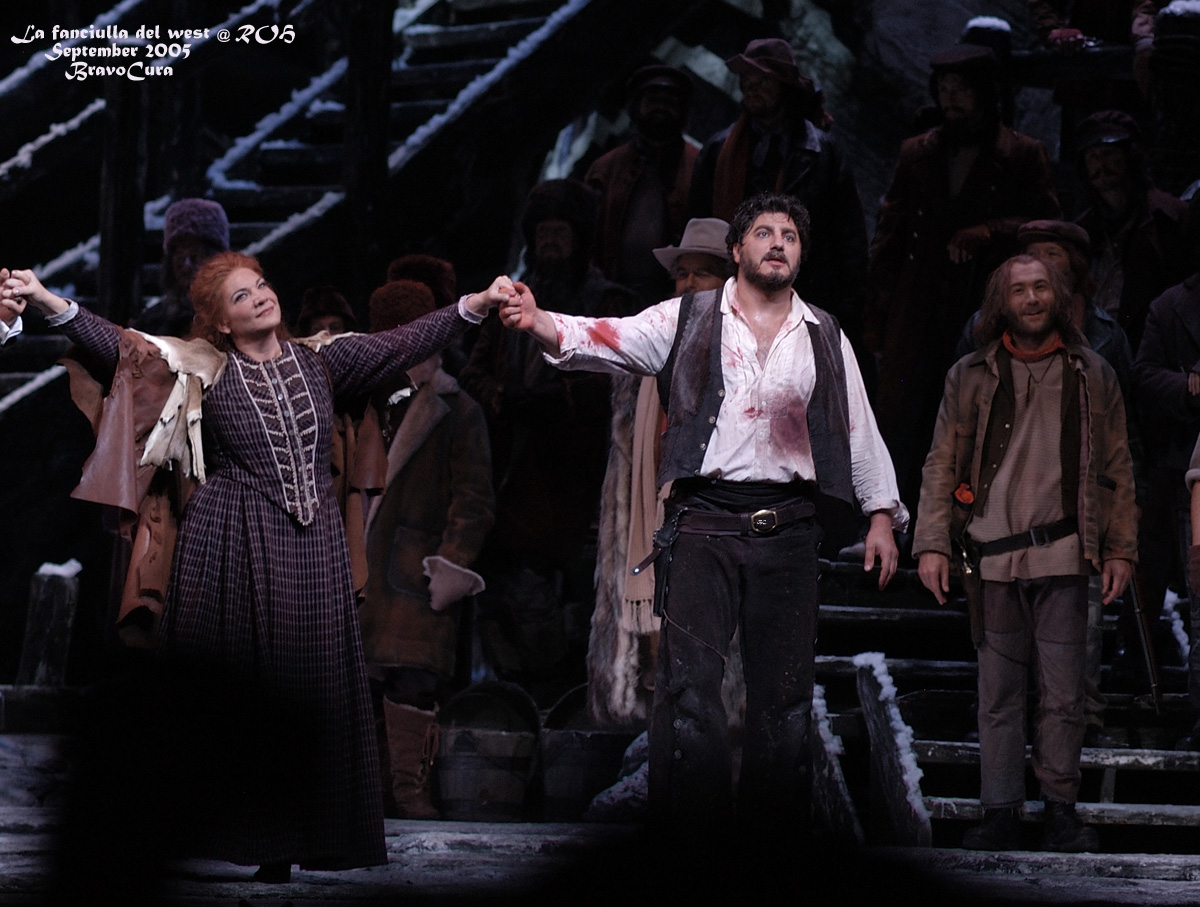

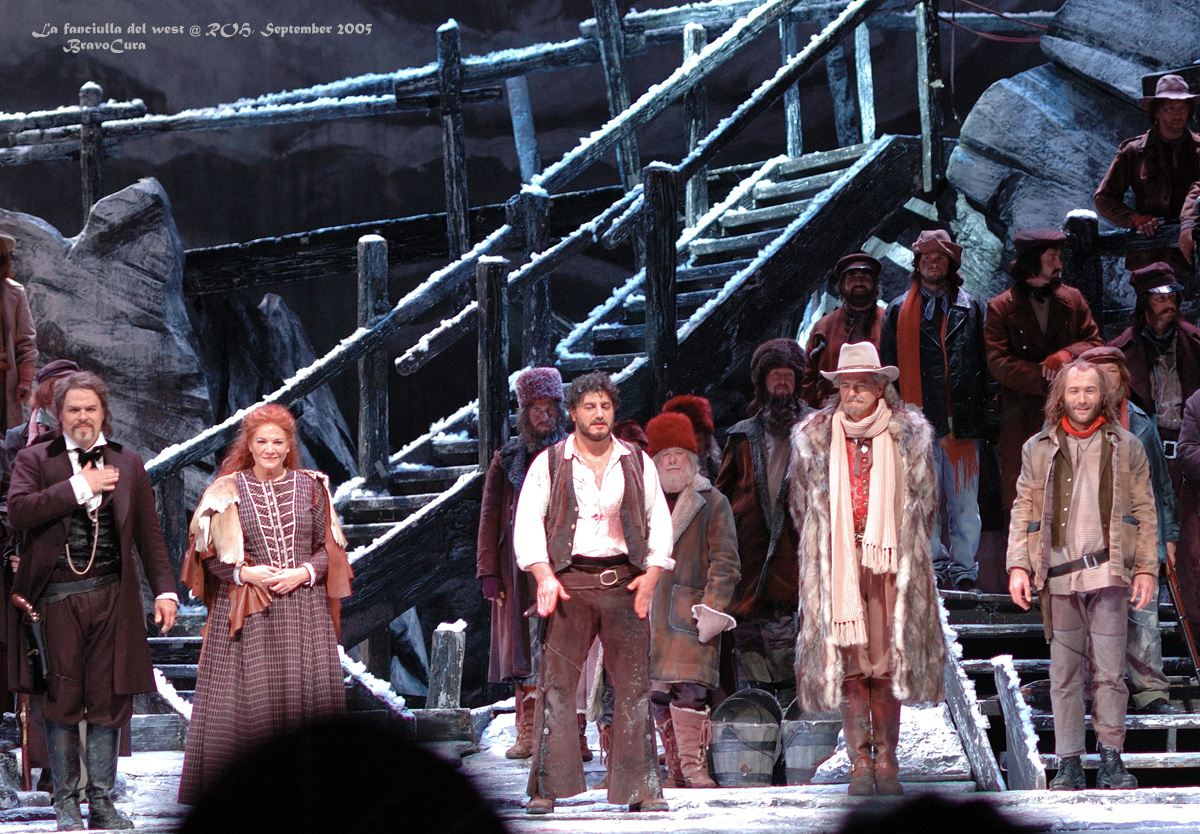

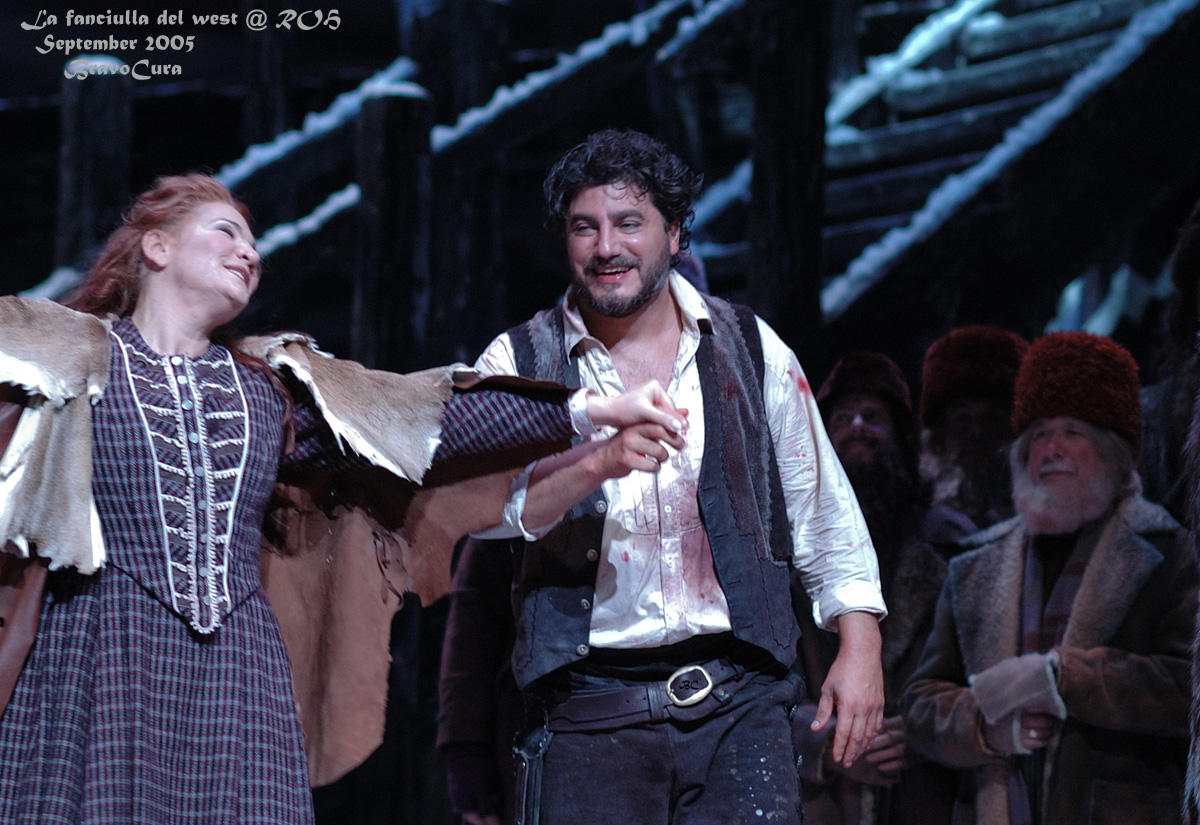

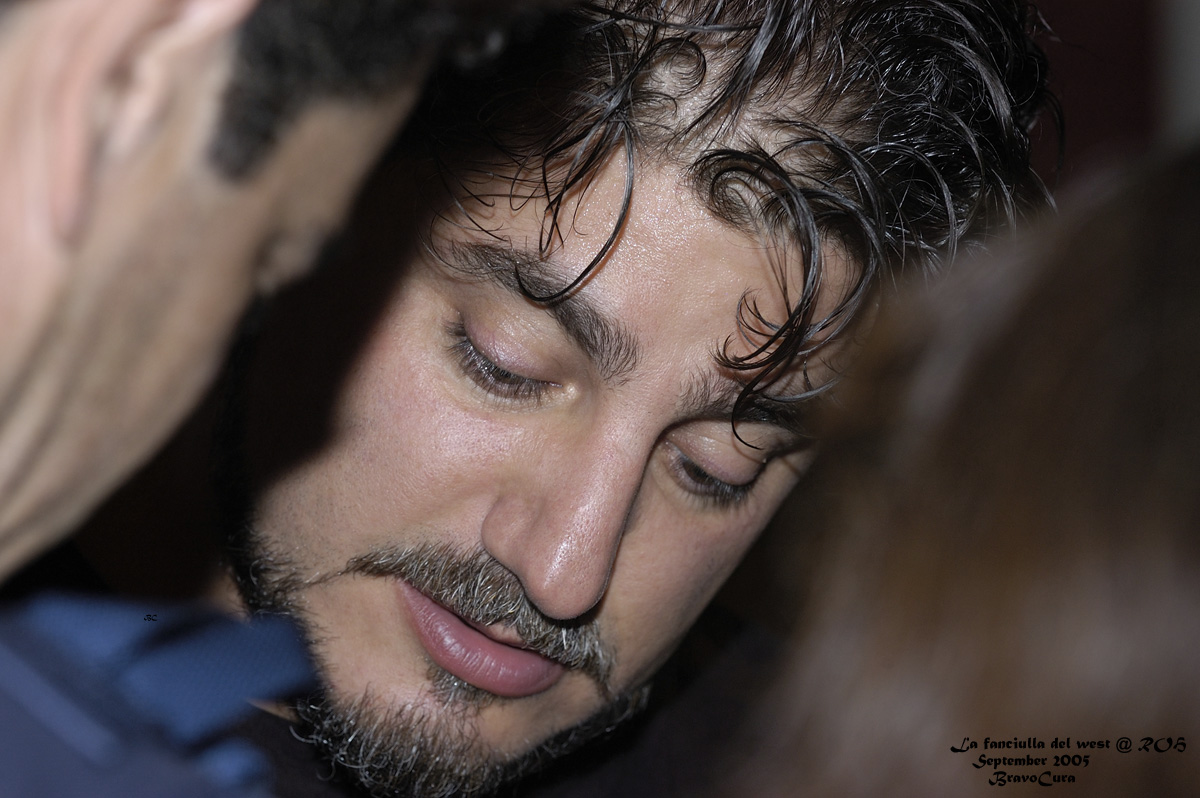

Fanciulla Retrospective - London

ROH 2005

|

|

Sound Files Click on the photo to hear the snippet |

|

Josť Cura talks about performing Dick Johnson |

|

|

Quello che tacete

|

|

|

Act I Ending |

|

|

Una parola sola |

|

Ch'ella mi creda (1) |

Ch'ella mi creda (2) |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

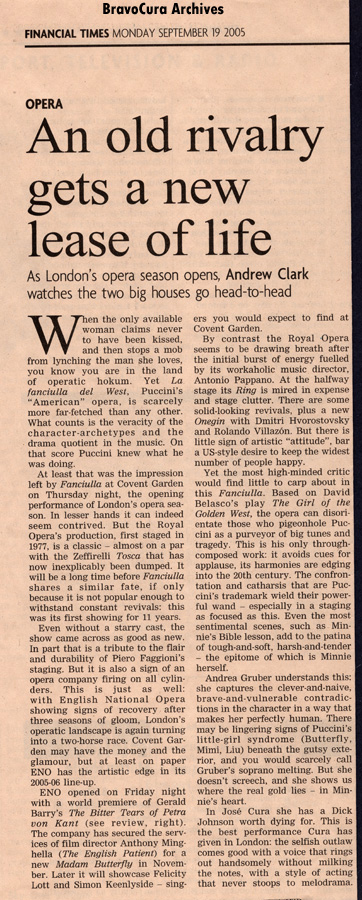

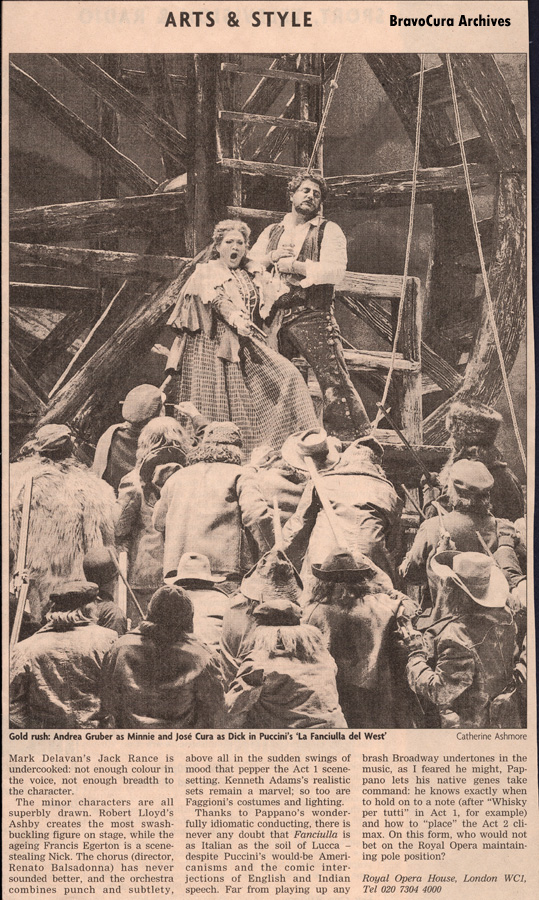

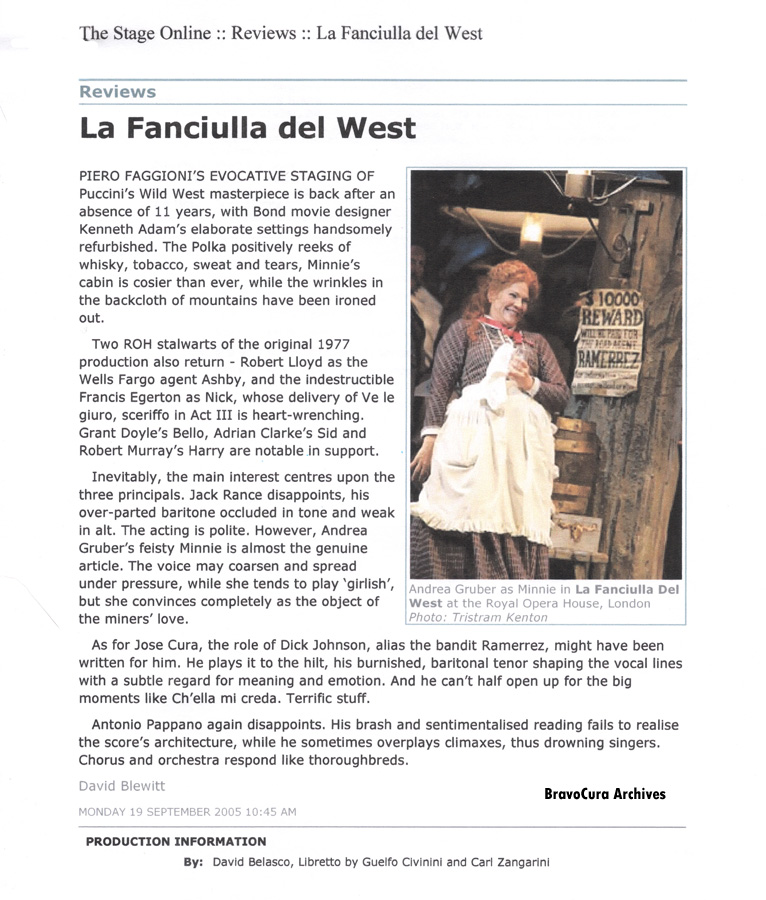

Press Associated with Fanciulla del West at ROH 2005

|

| The Cura for Airs and Graces

Irish Independent (Sunday) Ciara Dwyer 23 October 2005

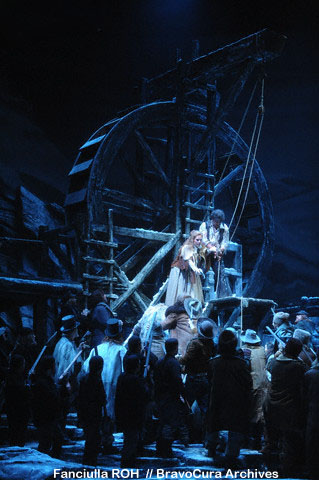

The shoppers who pass on the pavement are like pasty Lilliputians beside this glowing giant. He displaces air simply by standing there. It's like watching Marlon Brando in his prime - all that intensity and intelligence. But I am too scared to enjoy the sight. I am 10 minutes late and everybody knows how some tenors have a reputation for being temperamental. "I couldn't wait any longer," says Cura, "I'm starving. I need food." He walks away from the door of the apartment, where we were to do the interview, and heads off down the street. I gasp. Have I blown my big interview? I scurry after him. Moments later, the star tenor is pushing a trolley around Tesco, throwing packets of pasta and mozzarella and a pizza into his basket, while I, like a helpless diva, totter along the aisles beside him. Josť Cura is not your average tenor; for although he is extraordinarily talented, he is a very ordinary man. That morning he woke up in his Madrid home, had breakfast with his wife Silvia and their three children - Josť Ben, 17, Yazmin, 12, and Nicolas, 9. Then he got into his car, a Ford Focus, and dropped the kids to school, before heading for the airport. Nicolas was the last to get out. "Where are you going now?" the boy asked his father. "London." "And what are you going to sing?" "La Fanciulla del West." "OK. Ciao. Good luck." Cura, the doting father, smiles as he relates the beautifully blasť way of his child. He lugs his plastic Tesco bags back to the apartment and tells me he is tired. "All day yesterday I was doing my garden. Mowing the lawn and cutting hedges. At the moment we have no gardener and if I don't do it it will be a jungle. I was doing that from 10 in the morning till five, and in the middle I was on the phone, mowing with the headphone on, discussing contracts." In less than six hours, he will be performing as Dick Johnson in the Royal Opera House's production of Puccini's La Fanciulla del West. And he has agreed to let me interview him before this. Most opera singers don't stir before a performance. But Cura explains that that is not his way. "The important thing is living and not spending your day finding alibis not to live: 'I have a performance tonight so I cannot move' - that is a very common thing. OK, some people need that but most of the time it's just a stupid excuse. I find I do a much better performance when I enjoy my day. I forget about the performance until two hours before, when I need to get ready for it. "The other day, there was a march for peace here. [It was day he was due to perform.] So I went with my camera and stuck myself in the middle of the march, and started taking pictures. It was three hours before the performance. Then I went to the theatre and put my make-up on and sang. It's just living." Some might say that this is insane, not proper behaviour for a tenor, but Josť Cura has always done things his own way. Besides, he is not just a singer. The 42-year-old has been conducting for the past 25 years. He doesn't think of himself as a singer but as a musician who happens to sing and conduct and compose. Once, at a concert in London, he sang and conducted at the same time. Many years ago in La Scala, he was booed for singing an aria while lying down. And only last spring, he conducted Mascagni's Cavalleria Rusticana, then as soon as it was over he put on make-up and costume and played the lead role in Leoncavallo's Pagliacci. Such adventurous ways are not always praised. But Cura's path reminds me of the writer Antonio Porchia's line: "They will say that you are on the wrong road, if it is your own." "I am a daring artist," he tells me. "I am always investigating new ways of getting to the public. Not all of them work 100 per cent, but you study what does work, drop the useless and you develop. That's the way to grow in every human situation; if not, we would still be carving with stones. That's why for each generation since the beginning of time, you have two or three people who dare to challenge, and the other ones are just sitting there, either criticising or enjoying the results of your risks." The newspapers have chronicled his work. "Josť Cura is a phenomenally gifted artist. Seldom can anyone have made the hideously difficult title role [Verdi's Otello] sound so easy to sing," wrote the London Times's Rodney Milnes. The Daily Telegraph's Paul Gent raved about his "charm and charisma to burn, a thrilling voice with a dark centre and an athletic build honed by martial arts". And when the tenor returned to the Metropolitan in February of this year with Saint-Saens's Samson and Dalila, the New York Times wrote of his "animal magnetism" and hailed his performance as the reason to take in the opera. I have seen Josť Cura in many operas over the years and concur with the critic who described him as "thrillingly dramatic". Quite simply, Cura is a creature of the theatre, a male version of Maria Callas. Images of his performances remain in my head. When he was Manrico in Il Trovatore, I watched his side profile as he smoked a cheroot on stage, while the choir sang the Anvil Chorus; the way he put out the candle with his palm in Otello, then sang with fury, his lion-face on fire, as his Desdemona lay sleeping on the bed; pulling the pillars down in Samson. His voice, with its rich baritonal quality, is exquisite. And yet Josť Cura's singing career started by accident. In his home town of Rosario, he had been conductor of a young group which did chamber operas. One night, he settled into his seat in the audience to watch a concert which he had helped prepare, only to be told that the tenor had taken ill. Instead of cancelling the show, Cura stood in. "I was struggling, of course, because I was not a trained singer. But somebody heard me and said, 'You have to study, because there is some very interesting material to develop.' Fate is fate." In 1988, Josť had no money, but the singing teacher Horacio Amauri insisted on lessons - money was not an issue. "A voice like yours comes to the earth two or three times a century," he told Cura. Then in 1991, Josť and Silvia with their first child, left Argentina for Italy to pursue the singing. Later on, they lived in France and eventually settled in Madrid. "When we came to Europe we had some very tough years - working as waiters and cutting wood. It was tough but not scary. Today, I look back on it as an enriching period. I have always enjoyed my life, even when it was hard, because it's part of being alive. If you only enjoy your life when you are successful and well paid, then you are pathetic, because it's not the life that you are enjoying but the economical success of it." Today, as a tenor at the pinnacle of his career, he is grateful that he had to struggle. "To have an easy beginning is not advisable, because then you are a very tender thing. You have to make your muscles. You have to have what I call healthy rage. I have never accepted the mediocrity of giving up just because somebody says I will be at fault. If I have to do something, I do it and if I have to fight for it, I fight. Only the talent is given, but what you do with it is your own responsibility," he says. Cura attributes his success to hard graft. "The average audience will never understand the work behind a performance. Take a dancer, for example. To do a jump, he has to use muscles, he may have a pain in his knee. But in those 10 seconds that he is in the air, the audience sees this amazing creature, flying and smiling as if he is making no effort. They say, 'Wow! He is so lucky to be able to do this.' Lucky, sh*t. He's been working 10 hours a day for 10 years to be able to do that. It has nothing to do with luck." And so it is with opera. "I work very very hard. I study a lot and am very well prepared. That is why I am self-confident. I have been criticised because I look like I don't make any effort when I sing. I make a lot of effort but I have worked very hard, trained myself in front of mirrors and cameras, to make it look effortless. It's like if you see an actor acting, then he is not a good actor." Josť Cura is the full package - the former weight-lifter and black belt has the looks, the talent, the brains and a healthy sense of humour about life. But for years, his good looks proved a hindrance. "I never said I was a heart-throb, but people are impressed according to their own sensibilities. It is like if you take a tennis ball and you throw it against a wall, or water or the sun. You are throwing the same ball but it bounces differently according to the type of surface. " Now that Cura is going grey, and putting on a little weight, he is amused at changed perceptions. He tells me about a concert he conducted recently, where he heard the audience laugh when he put on his glasses. "I turned around and said, 'Well, it happens to everybody sooner or later. Now that I wear spectacles, you will say that after all that, I was not a bad musician'." If ageing means that he will be taken for the serious artist that he always was, then "getting old is good", he says. Now that he is in his prime as a tenor, he is happy to sing more than conduct, but when he gets older, he plans to tilt the scales in the other direction. "For sure I will keep singing until I finish paying my mortgage - 15 years to go." There was a time, a few years ago, when he was so disheartened with the opera world that Silvia, his staunchly loyal wife, told him they would sell the house, and get somewhere smaller, so he could be free and happy again. Luckily, he rediscovered his enthusiasm. Setting up his own production company and record label - Cuibar - helped. Now he is his own impresario. "It is extra headaches but it's nice. Life is about colours and moving and preparing for your future." Cura is still talking but I am conscious of the clock. There is the matter of tonight's opera. He needs to rest. After all these years he still strikes me as incredibly down-to-earth. In a world where singers can become precious, how has he remained so grounded? "You only stay grounded if you want to be. If it wasn't for the support of my family - my wife, my kids, my parents - I wouldn't have got so far. It depends on the kind of family you have. If you have an iron ball on your leg, you will move eventually but each step will be a nightmare. On the contrary, if your family is like a balloon, you just get everybody on board and you fly together. " That evening in La Fanciulla del West, I watched Josť Cura on stage as a cowboy, with spurs, hat and gun. As always, his singing looked effortless, but sounded sublime. "When I am on stage I give my blood," he told me that afternoon. On that Covent Garden stage, I watched him bleed. His dynamism was mesmerising. It was like watching history being made. I sat in the audience, glowing like a proud mother. For I am privileged to have met this man who has been touched by the gods, to have heard his story and to have shopped with him in Tesco.

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

%20Sept%2008.jpg)

%20Sept%2008.jpg)

.jpg)

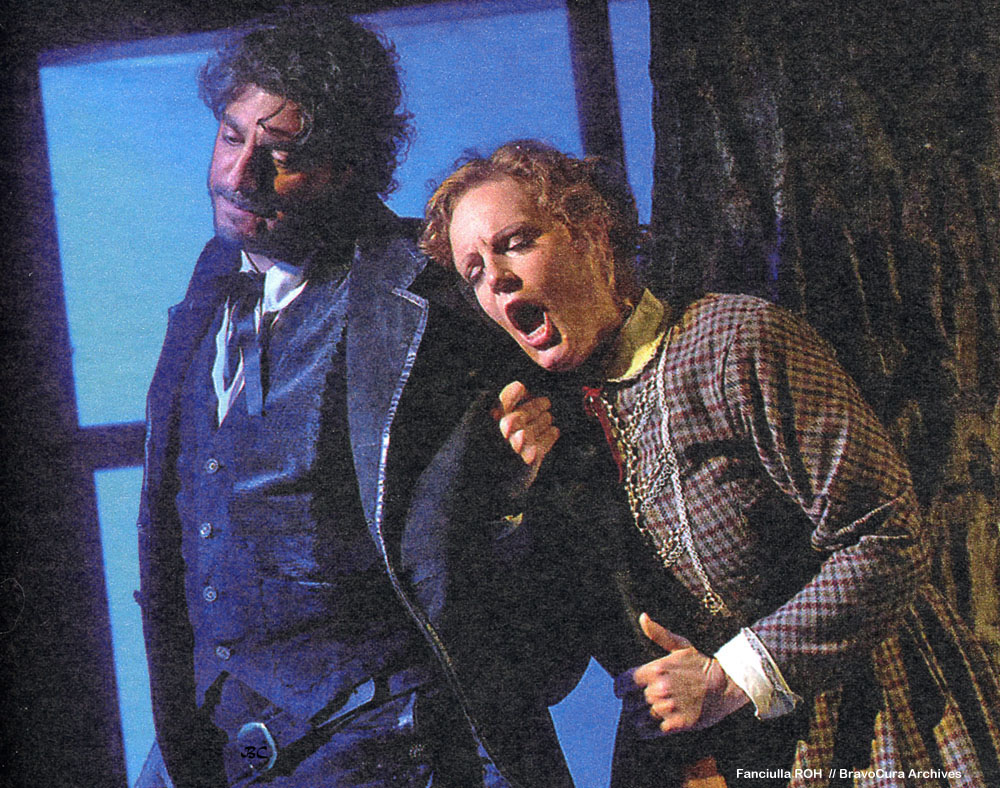

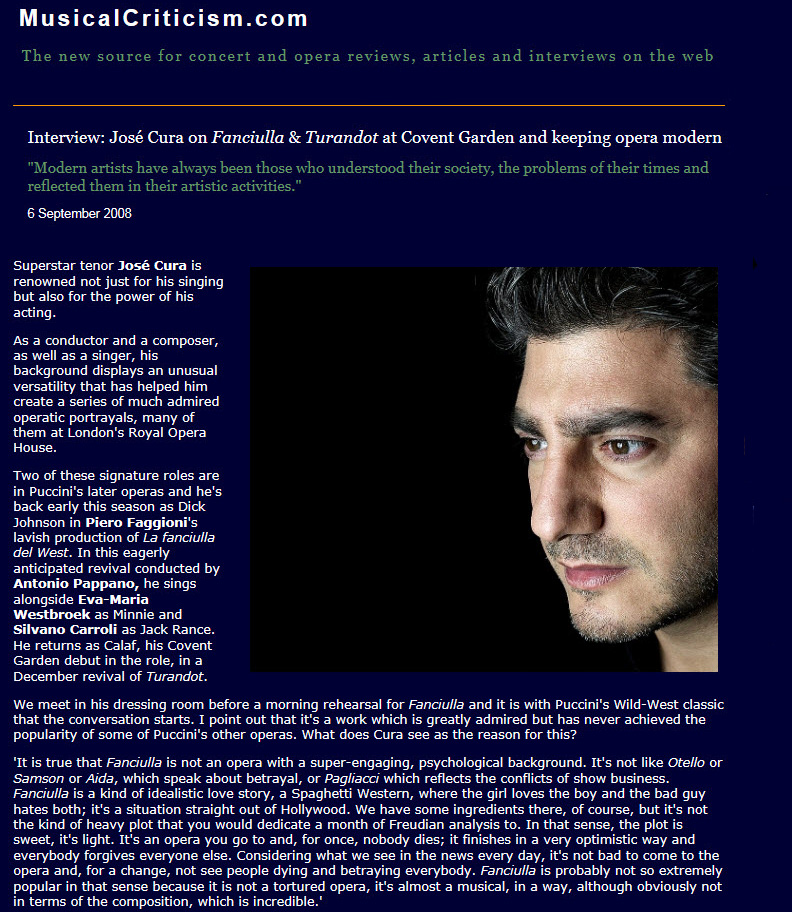

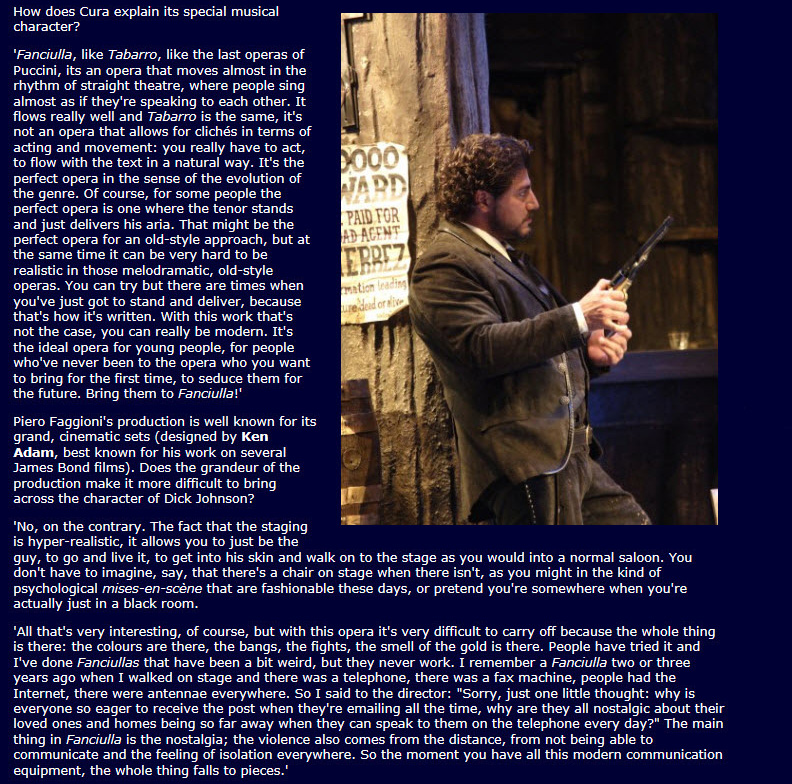

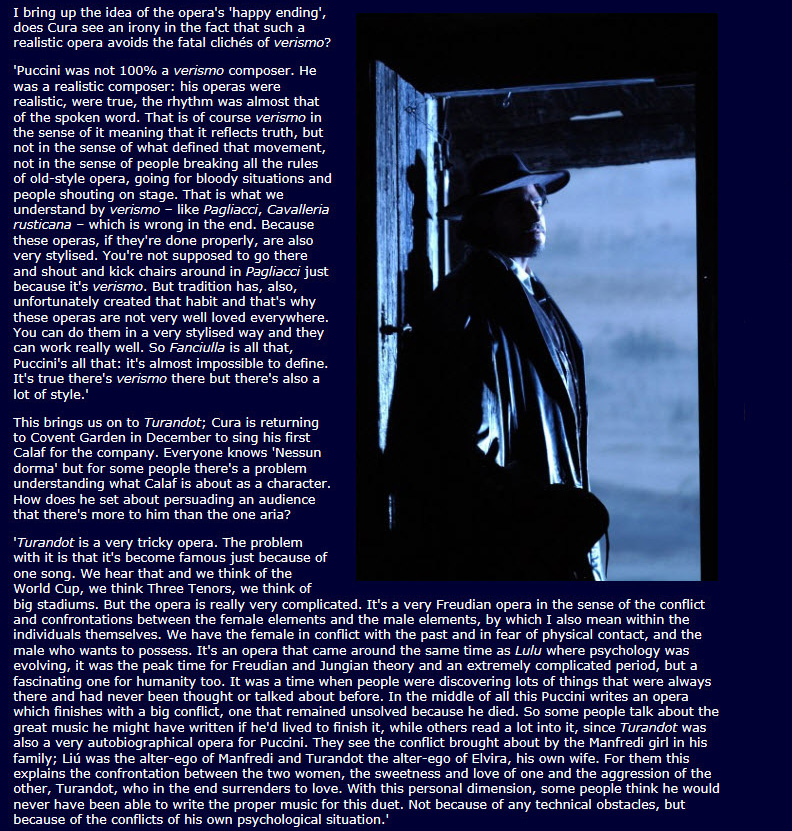

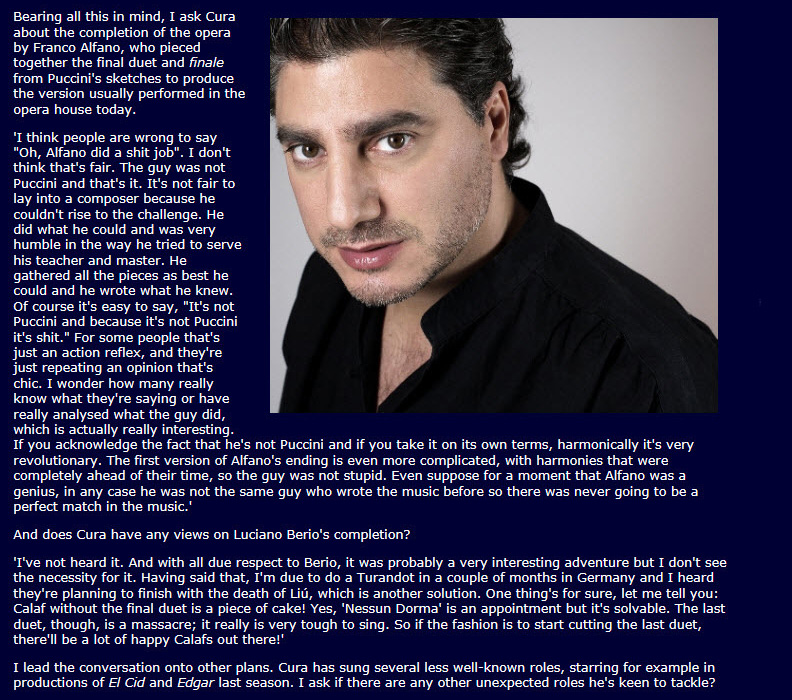

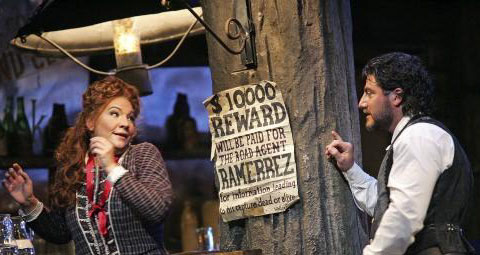

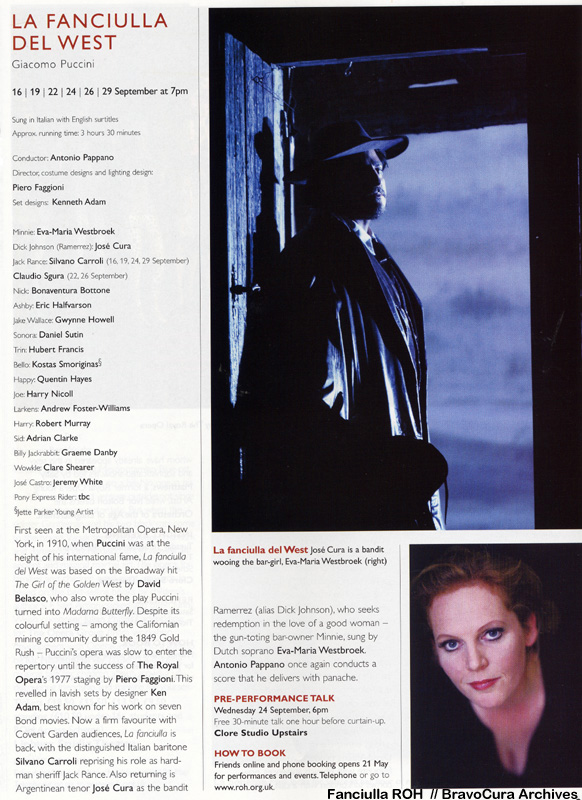

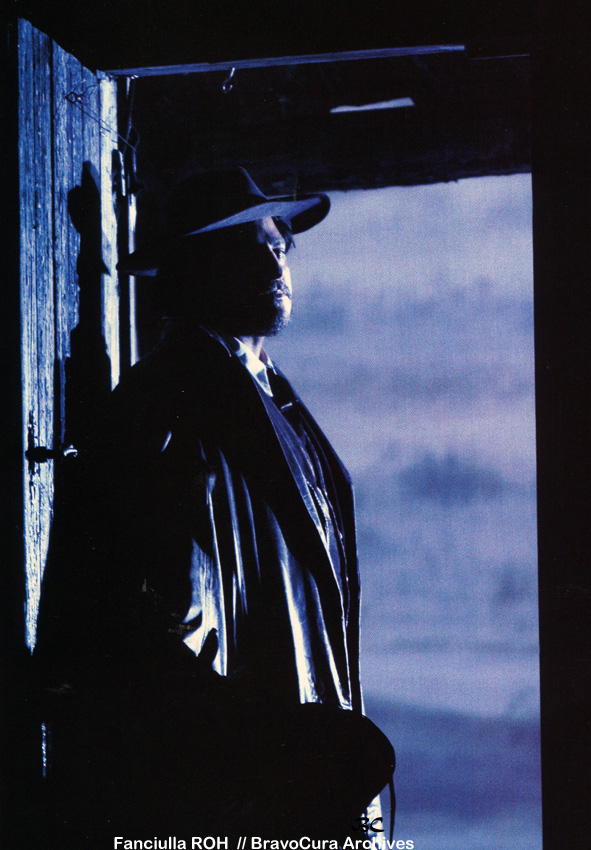

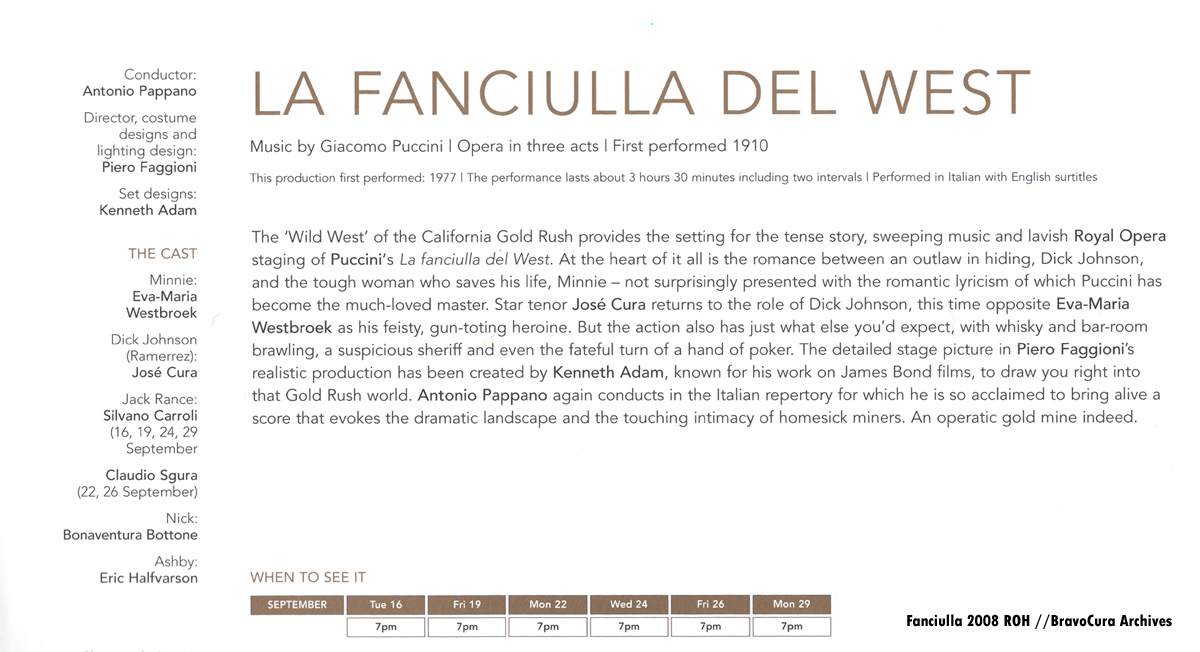

Josť

Cura breezes in from his rehearsal at the Royal Opera House

looking rather like an off-duty nightclub bouncer. The

dark-eyed Argentinian superstar, a former rugby player and

body-builder, could have been tailor-made for the tenor lead

in La Fanciulla del West, Puccini's take on

the gold rush, for which he received rave reviews last week.

His character, Johnson, aka Ramerrez, is an escaped Latin

bandit, by turns a "goody" and a "baddy" in the best

tradition of spaghetti westerns, but - in the best tradition

of romantic opera - ultimately redeemed by love. Cura has

run the gamut of "goody" and "baddy" in terms of critical

opinion over the years, but it's his passion that carries

him beyond that. His treacly, seductive, dangerous voice can

knock you into submission in seconds.

Josť

Cura breezes in from his rehearsal at the Royal Opera House

looking rather like an off-duty nightclub bouncer. The

dark-eyed Argentinian superstar, a former rugby player and

body-builder, could have been tailor-made for the tenor lead

in La Fanciulla del West, Puccini's take on

the gold rush, for which he received rave reviews last week.

His character, Johnson, aka Ramerrez, is an escaped Latin

bandit, by turns a "goody" and a "baddy" in the best

tradition of spaghetti westerns, but - in the best tradition

of romantic opera - ultimately redeemed by love. Cura has

run the gamut of "goody" and "baddy" in terms of critical

opinion over the years, but it's his passion that carries

him beyond that. His treacly, seductive, dangerous voice can

knock you into submission in seconds.

.jpg)