|

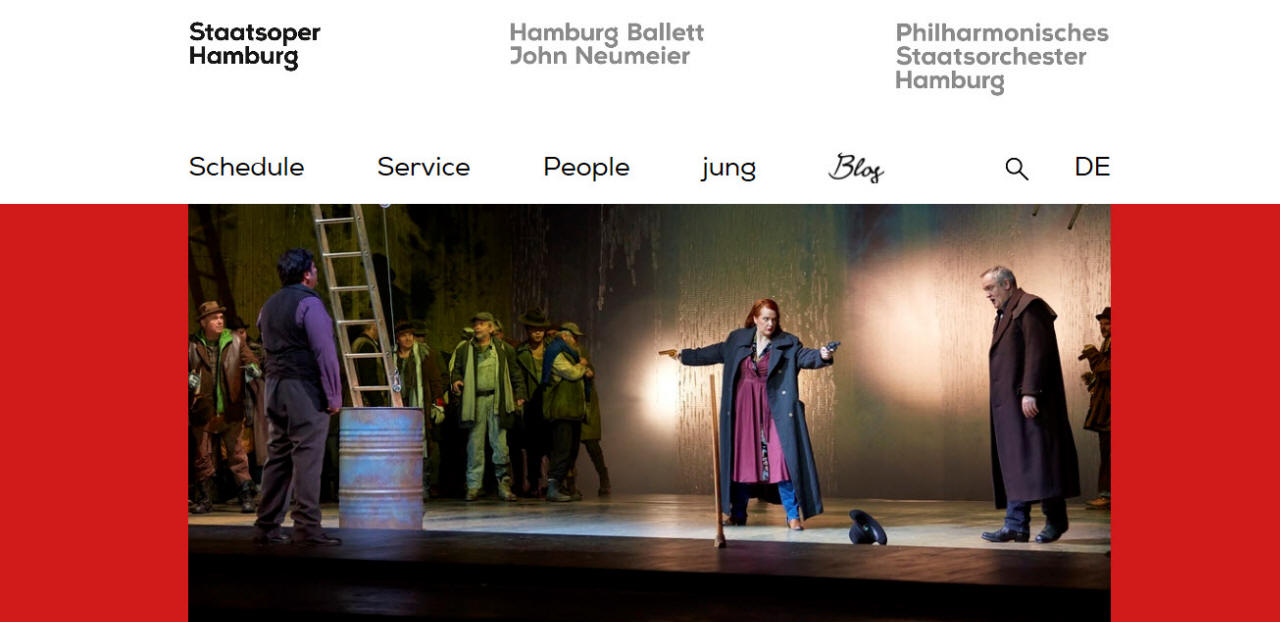

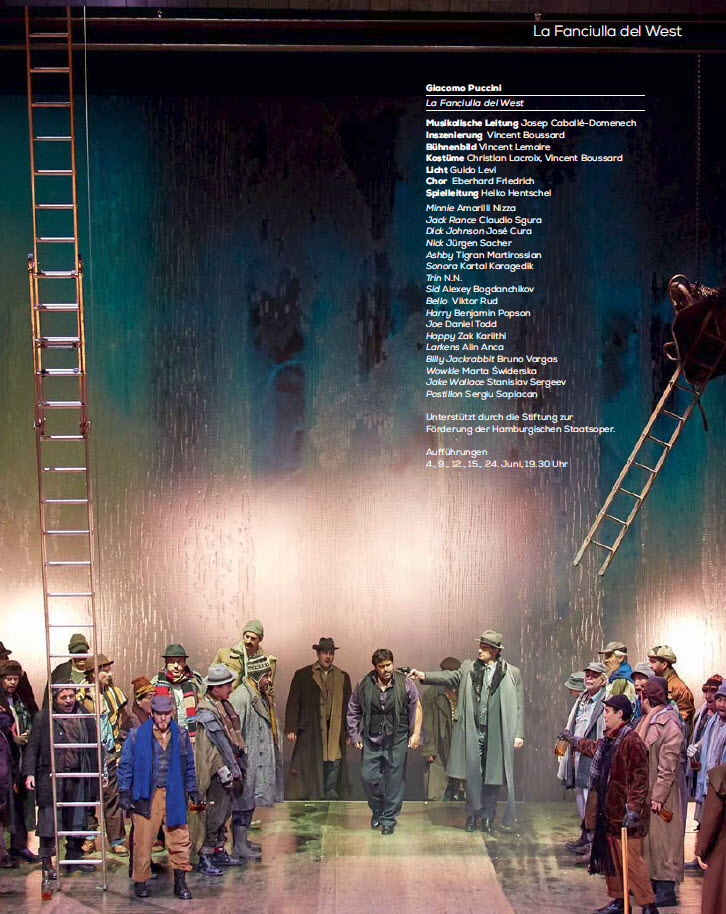

Fanciulla, with its

six-shooters and saddles, cowboys and Indians, macho

posturing, fist-fights and rough frontier justice,

may appear to be constructed of “Old West”

canvas but its heart is made of more delicate

fabric. Director Vincent Boussard’s uneven staging

embraced that larger, sturdy canvas while allowing

the finer material to unravel.

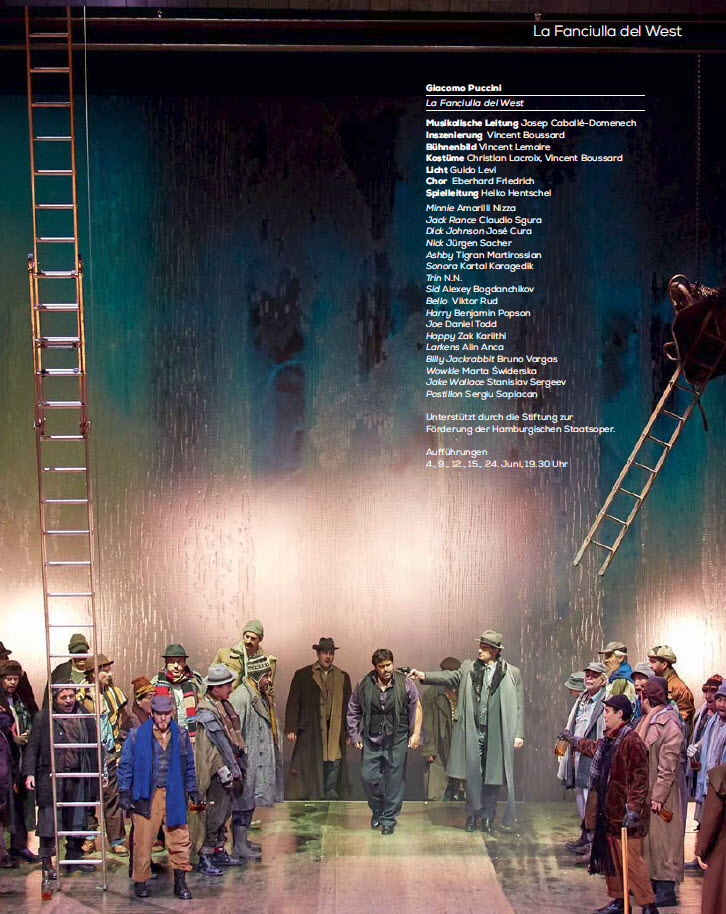

The large scale elements were in place in act I: the

Polka was suitably rustic, the miners suitably

scraggily, the atmosphere suitably evocative. But

the very long bar was placed forward and ran

parallel to the audience, effectively blocking the

view of many whenever the action took place behind

it and the obligatory effort to shock—the

introduction of the Marilyn Monroe minstrel-in-drag

singing the nostalgic “Che faranno I vecchi miei”—fell

flat. Totally missing was the charm and whimsy

inherent in the music and libretto: Minnie’s

entrance lacked drama (she wandered in), Dick

Johnson’s entrance with his mini-saddle wasn’t

impactful, and the sweet waltz in which the virginal

Minnie submits to Johnson sadly took place

off-stage.

Act II fared little better. Again we had the big

canvas—Minnie’s single room hut was strangely tilted

with no bed, no fireplace, no appliances but

featured a floor-to-ceiling mirror and huge crystal

chandelier—but little heart. The obligatory effort

to shock was the sudden dropping of the curtain when

Johnson gives Minnie her first ‘kiss’; when it rose

the two were on the ground in each other’s arms with

the chandelier now hovering just off the floor,

obscuring half the stage. A few tossed bits of

clothing would have been as effective and less

visually disruptive. Unfortunately, Boussard writes

Johnson out of the act after the bandit is shot: the

wounded man doesn’t move for the rest of the act and

no one takes notice of him. Since Minnie and Rance

gamble for the life of the bandit, having the

bandit’s presence front and center re-enforces how

high the stakes are; however, in this production,

neither Minnie nor Rance ever even look toward the

bleeding (and presumably dying) man as the essential

trio becomes a duo. The music churns and the

emotions rise in response to the genius that is

Puccini: alas, there was no sense of urgency or

emotional attachment coming from the stage. Even

when Minnie finally wins, she laughs and throws

cards around rather than rushing to her love. She

seems more excited to have beaten the sheriff than

rescuing Dick Johnson.

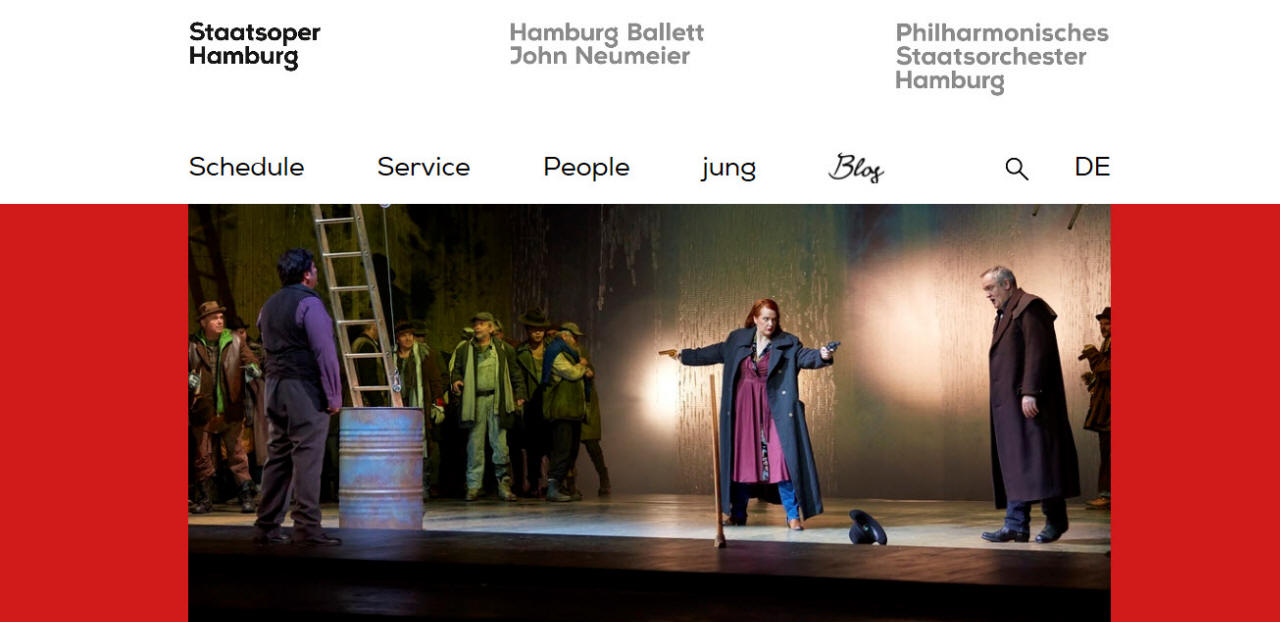

Without the effective psychological underpinnings

that come from Act II, Act III becomes all canvas.

Johnson is brutalized and Minnie saunters on stage,

showing little desperation or drive. She waves her

guns around, Rance acts menacingly until he runs

away, Johnson remains stoic, the miners have a

change in heart. One of the most delightful,

romantic, uplifting operas in the canon ends with a

whimper. The fabric that was the heart seemed

shredded.

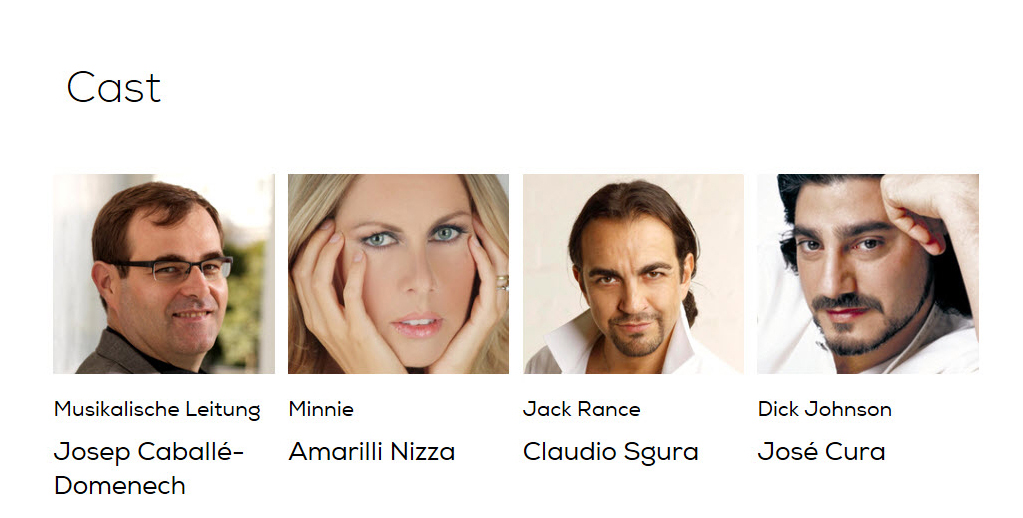

Whether due to direction or personal choice, Minnie

(Amarilli Nizza) came across as self-reverential and

unsympathetic; her voice tended to be shrill. Rance

(Claudio Sgura) was dour and one-dimensional,

somewhat hammy, though he sang well. Johnson was

well served by the ever charming José Cura who

brought his usual charisma to a role that suits him

like a favorite pair of jeans. He sang beautifully,

added lovely little touches that brought depth to

his character and seemed to have the time of his

life, but he had to struggle mightily to bring life

to the stage against a series of directorial

challenges.

The orchestra under the direction of Josep

Caballé-Domenech was disappointing: sour notes,

off-beat, too loud, out of sync—they seemed closer

to an amateur ensemble than an established, working

orchestra. Excuses were given, explanations were

made but the bottom line was that they too often

sounded like they were doing a first read-through of

the music. That they consistently overplayed the

singers and seemed incapable of any nuance reflected

control issues by the conductor. The artists on

stage, the audience and Puccini deserved better. |