Bravo Cura

Celebrating José Cura--Singer, Conductor, Director

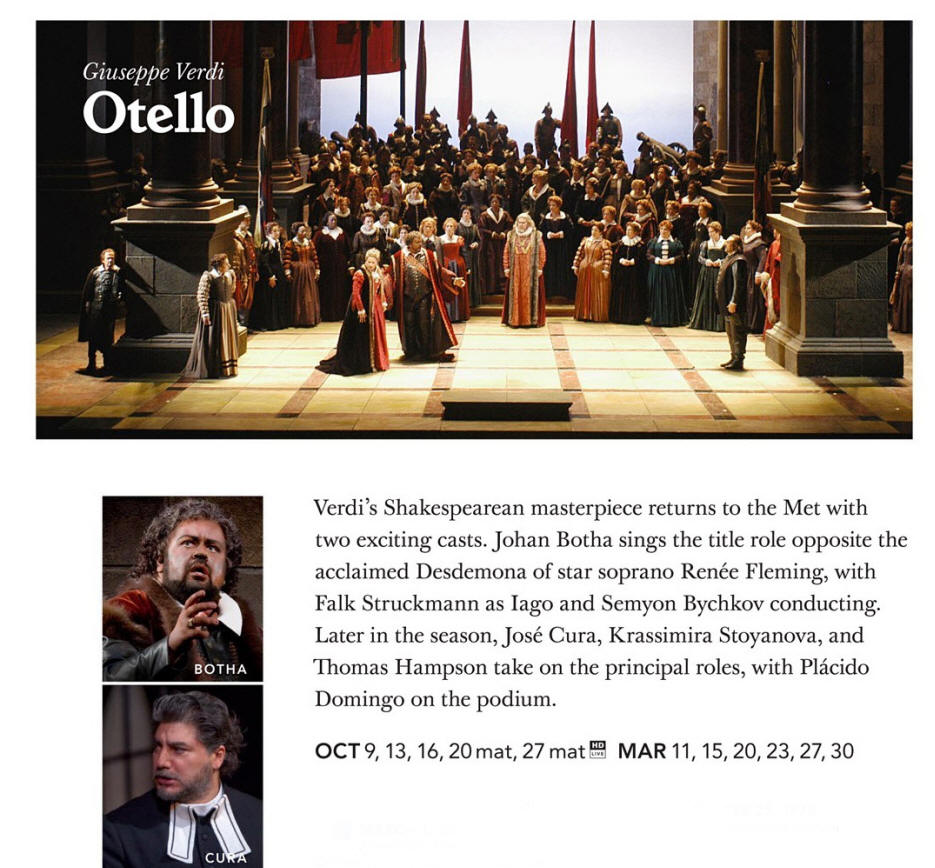

Operas: Otello

Otello - New York City - 2013

|

|

|

|

[Excerpts]

|

|

|

|

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.

José Cura performs his "particular" Otello at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. RTVE 16 April 2013 [Excerpt] Tenor José Cura (Rosario, Argentina, 1962) has just presented his ‘particular” Otello at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, "an Otello that has taken me 15 years to mature, so I have an authority behind the character that allows me to do things in a certain way." "A lot of people” he stated, “are annoyed that I recreate my Otello as a vile, nasty, insecure being. Because opera is an art form that still thinks that the tenor is always the good guy; the baritone, the bad guy; the soprano, the poor girl and the mezzo-soprano, the prostitute..." The Argentinean, nationalized Spanish, always goes one point further in his analysis and points out that "without having the gift of infallibility, my analysis is that Otello is an apostate, a former Muslim and Christian, who has been hired to kill Muslims, which makes him a traitor. In addition, since he is not Venetian but African, he does not fight to defend his homeland but as a soldier for hire, a mercenary, an assassin." Cura does not feel that his interpretation proposes profound changes in the meaning of the opera, but allows him to do what the composers of operatic works, and in this case Verdi, dreamed of doing with them, without limitations or obscurantism. The tenor draws attention to the stagnation of opera, stating that while theater, ballet and cinema have evolved opera is still anchored in the 1940s and 1950s. He is in favor of a profound transformation but he is also aware of the great difficulties of that which he attributes, fundamentally, to the large size of the productions and to the large number of people needed in the current scheme to justify an opera production.

|

|

|

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.

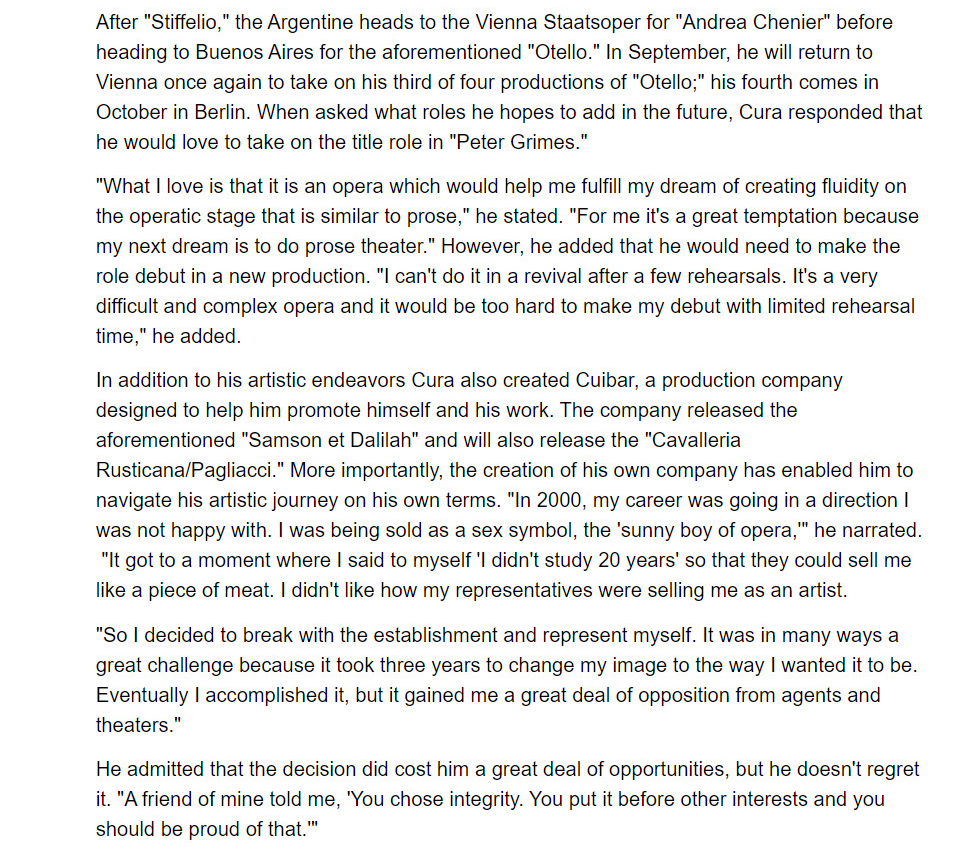

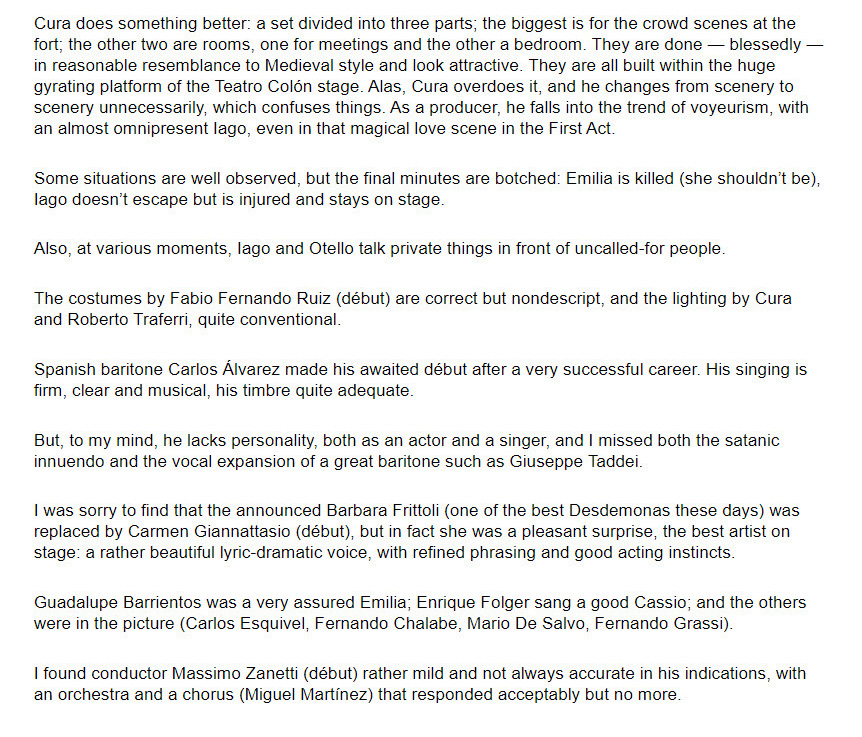

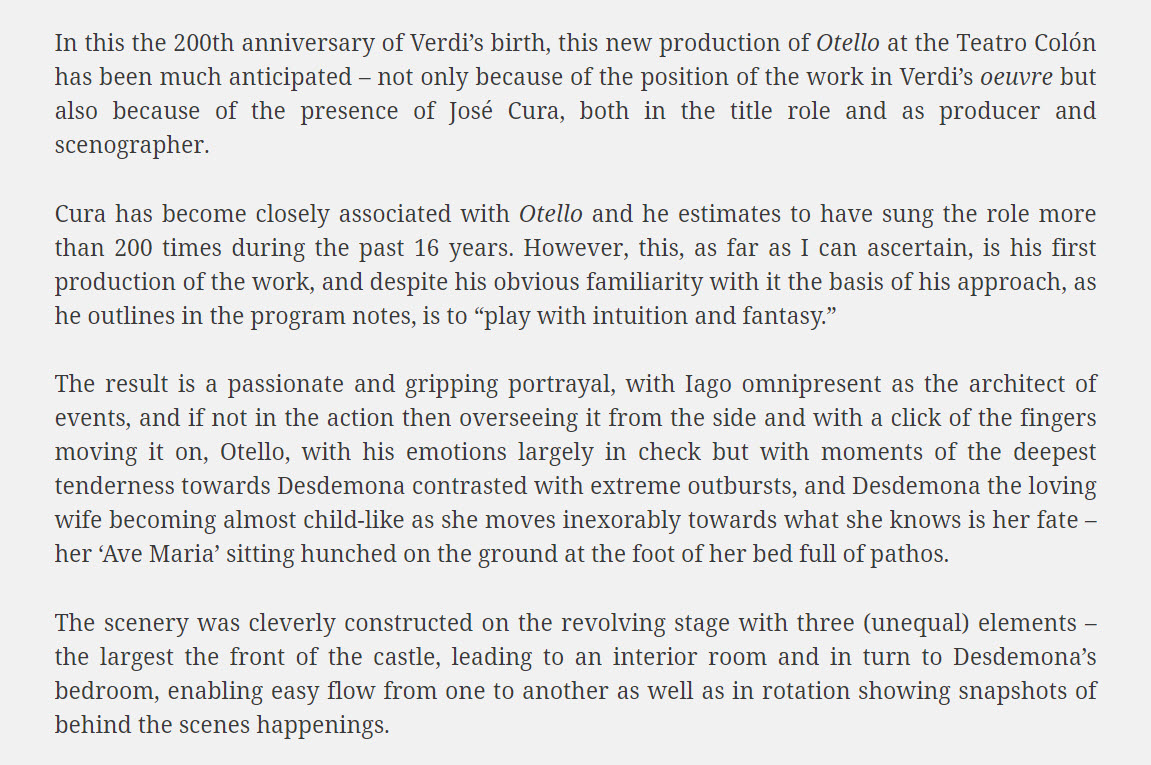

NEW YORK, METROPOLITAN: OTELLO

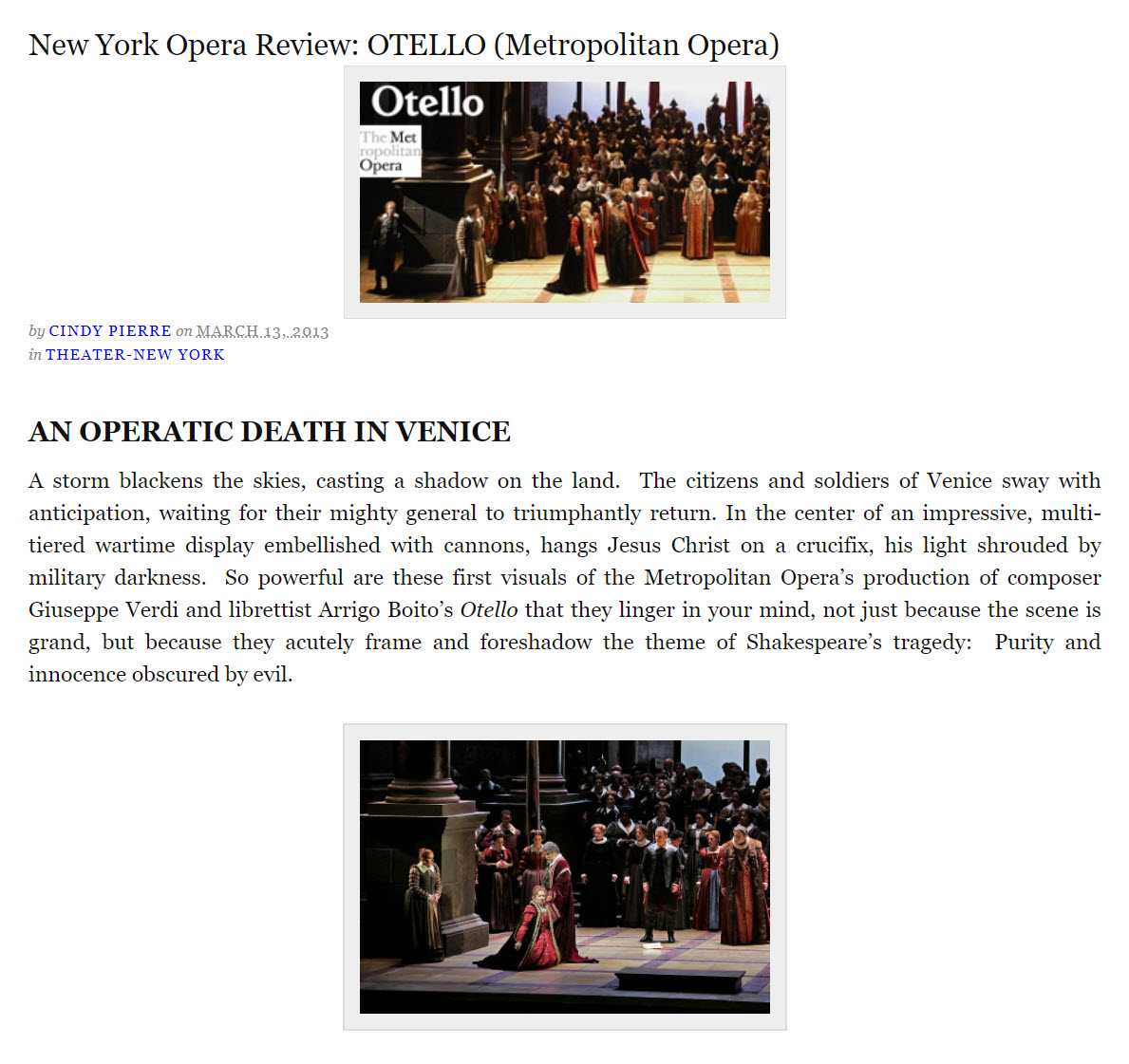

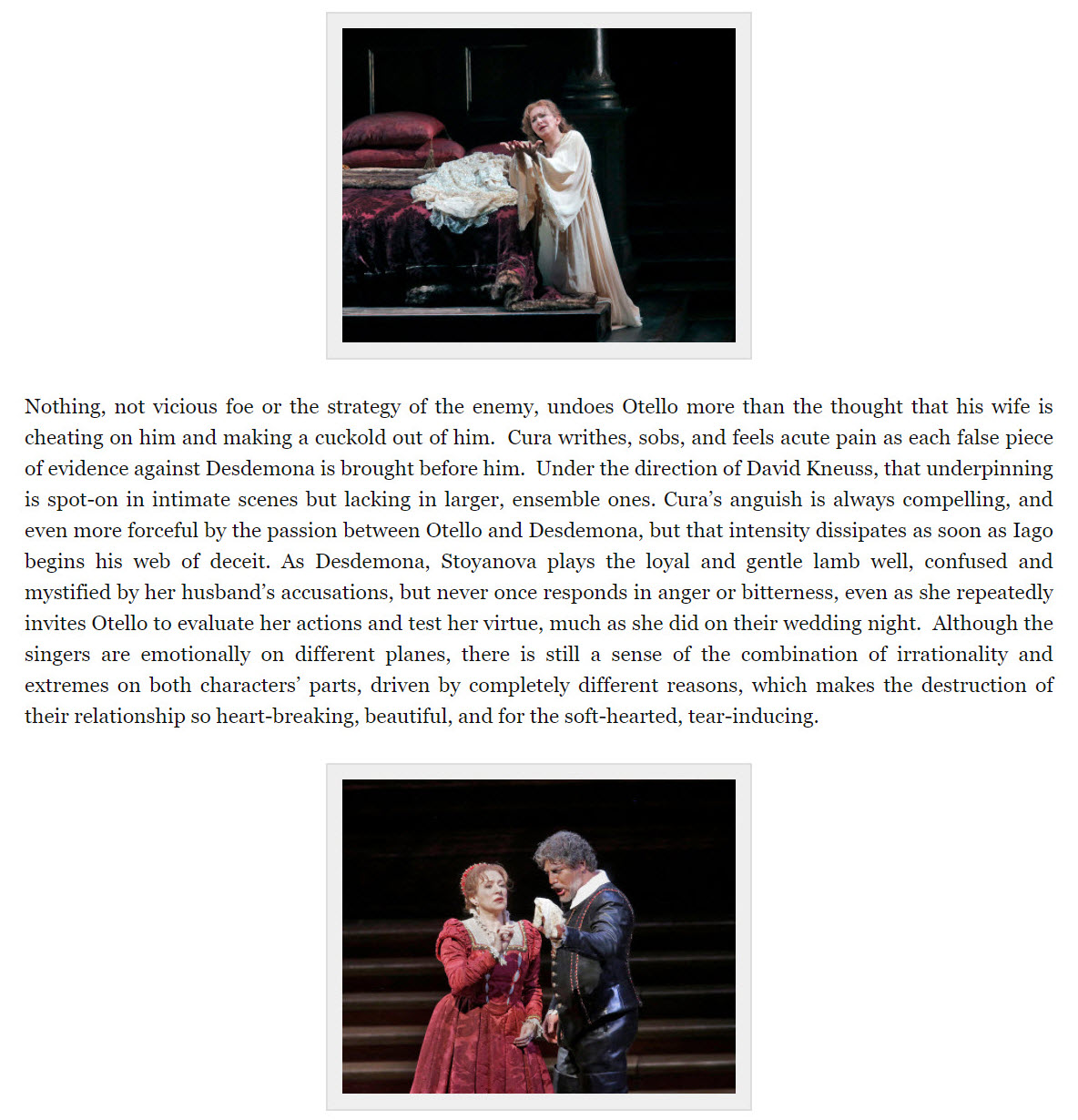

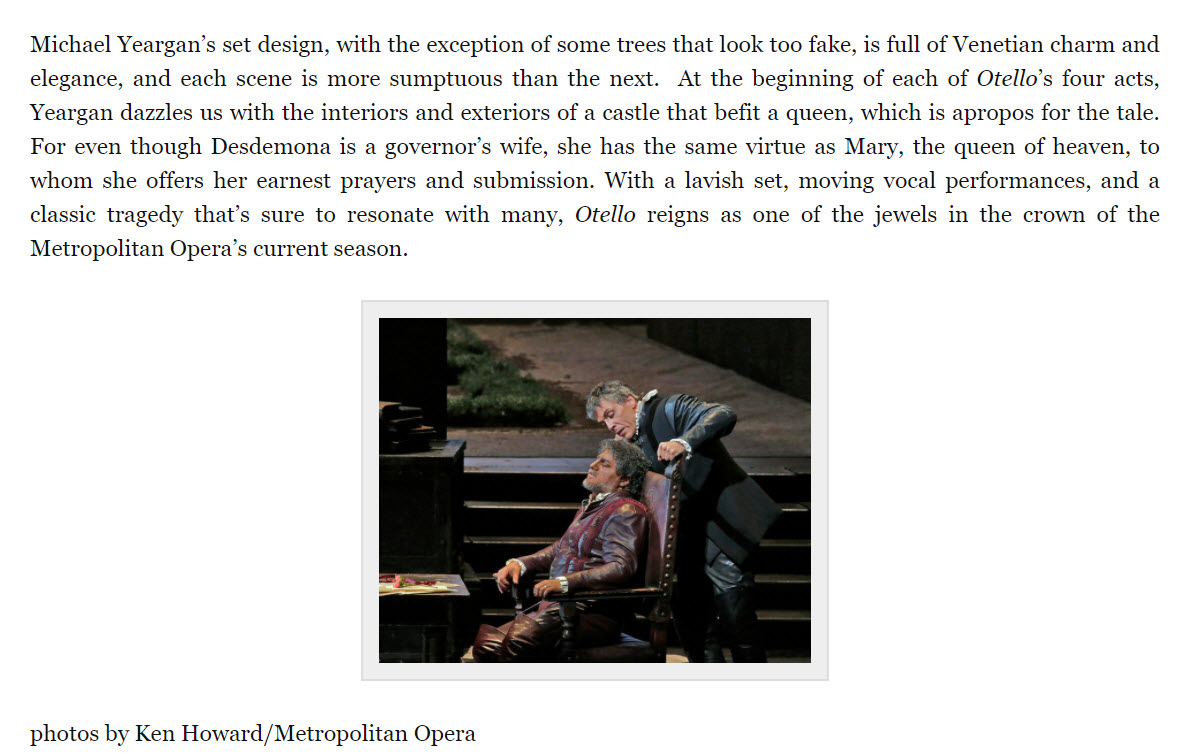

GBOpera William V. Madison 22 March 2013 [Excerpt] Verdi’s penultimate opera returned to the Metropolitan on 11 March for just three performances, after an absence of several months. None of the three lead singers, José Cura, Krassimira Stoyanova, and Thomas Hampson, had sung these roles before in this theater, and particularly because Cura’s Otello has won acclaim around the world, interest ran high. The first two acts found the Argentine tenor anxious and evidently in a hurry to be through with the opera altogether. While French conductor Alain Altinoglu strove vainly to keep pace with him, Cura sped ever onward; his voice sounded ragged, and his pitch proved unreliable. After the intermission, Cura recovered much of his vocal poise and showed himself far more willing to adjust his tempi to those of the conductor and of his colleagues; by the end of the evening, he delivered a musically and dramatically effective Act IV. Yet this was at best an adequate, not a first-rate Otello, a missed opportunity for New Yorkers and for Cura himself. As a sometime conductor and stage-director, Cura may have brought his own ideas to this mid-season revival of Otello, for which rehearsal time was limited. It’s unclear, for example, whether he simply forgot to strike Desdemona in Act III, Scene 2, or whether he believes that Desdemona is by this point so psychologically abused by her husband that she kneels at his command (likewise, it was unclear whether Desdemona was stunned by Otello’s behavior, or whether Stoyanova was stunned by Cura’s failure to hit her). With curiously weak gestures, Cura never managed to offer much opposition to Hampson’s Iago, who dominated Otello from start to finish. Much of the present performance required more damage-control than artistic expression on Antinoglu’s part; it speaks well of the Met musicians that they managed to respond alertly to his cues and to deliver an otherwise reasonably coordinated, coherent performance — it’s not likely that many other orchestras could do the same. But by then Verdi’s music has worked its magic spell, and even the impetuous José Cura must submit to it.

|

|

|

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.

José Cura: "If everyone likes you, it's because you don't do anything new"Expansión Estala S Mazo 11 April 2013

[Excerpt] The tenor claims the right to perform without the yoke of tradition. He has a reputation for being unconventional. For breaking rules. Or "patience," as José Cura (Rosario, Argentina, 1962) says from backstage at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, where he had had just performed as Otello. But not just any Otello: "The one I play now has taken me 15 years to mature, so I have an authority behind the character that allows me to do things in a certain way. You can agree or not, but you cannot not tell me that I am wrong," he explains to Expansión. And the fact is that his representation is not conventional either. "A lot of people have been annoyed that I recreated Otello as a vile, unpleasant and insecure being." Why? "Because it is an art form that still thinks that the tenor is always the good guy; the baritone, the bad guy; the soprano, the poor girl; and the mezzo-soprano, the prostitute. It can’t be, we live in a haze…”

Hence, the Argentinean, nationalized Spanish, breaks rules. But it is not a whim but the product of reflection. "Without having the gift of infallibility, my analysis is that Otello is an apostate, ex-Muslim and Christian and is hired to kill Muslims, which makes him a traitor. Moreover, since he is not Venetian but African he does not fight to defend his homeland, but is a soldier for hire, a mercenary, an assassin." This vision clashes with the traditional, with those who do not understand the revolution that Cura proposes for the opera. "It’s not about the changes but rather to do once and for all what the composers of the works dreamed of doing with them, without fear that a whole brotherhood of priests of vocal and operatic obscurantism will tell us how to do things," he explains. “He understands that today no one would tell a prose actor to speak as he did in the 1940s, but "we do." Thus, while theater, ballet and cinema have already made the transition, "opera is still anchored in the 40s and 50s. How can young people not be put off by opera if you go to the theater and see a man standing in the middle of the stage with his arms wide open, singing at full blast with a knife in his belly?" he asks. The transformation won't be easy, as stereotypes are "very entrenched." "For example, producing an opera requires no fewer than 250 people, and the bigger the mass, the more impossible it is to stop the inertia." And the genre itself is not easy to embrace either, as it requires effort. "We have always hidden behind the argument of the elitism of classical art to justify our laziness in not approaching it," he says. And the fact is that this art comes with a condition: "The level of enjoyment it provides is directly proportional to the amount of time you have invested in preparing yourself to understand it, because it is neither obvious nor free." That effort is precisely what makes it elitist. On the other side of the stage, he has a piece of advice for a newcomer to opera, which he borrows from Oscar Wilde (attributed): "Be yourself. Everyone else is already taken." "You can go through life as a clone or as an individual.... If everyone likes you it's because you're not doing anything new. If no one likes you it's because what you're doing is crap. You have to find the middle ground." He makes the same commitment to his characters, which he prepares by "studying the score, thinking about it and looking at the implications." Once he finishes his analysis, he consults the story to see if he was wrong in his conclusions. "I look at it at the end because if you do at the start you might conclude what others have concluded." His favorite? "The librettos that work, that have continuity and logic, like Otello, Samson, Carmen, Tosca." In real life, he admires "many people" but "I won't tell you who because if I do people will wonder why." Less mysterious is what one of opera's greats listens to on the radio at home or in the car. "When you work in music constantly, your ideal music is silence."

|

Otello - Buenos Aires - 2013

|

|

|

OTELLO AT THE TEATRO COLÓN (English version Monica Belew) TIME FRAME Even though there were plenty of battles between the Venetians and the Ottomans during the 16th century, I have chosen to set my Otello production in the year 1571, after the Battle of Lepanto. This epic conflict between a Christian coalition and the Ottoman Empire is among the most legendary naval battles in history. Why Lepanto and not another battle? Shakespeare does not make clear which conflict he had in mind, and Giraldi Cinzio (or Cinthio), on whose novel the Bard based his play, does not mention a battle at all… So here is where the director’s freedom to imagine a place and a time enters the picture, and in this, my picture, one man figures prominently: Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra. The number of quotations directly or indirectly mentioning Lepanto in “Don Quixote” is huge, so I couldn’t resist the temptation of using the voice of the legendary “Manco de Lepanto”, to introduce the show. SETS The characteristics of the set will be those of the “Brechtian epic theater”: a black curtain surrounding the entire stage (no pretension to spatial realism); the walls of the Castle “cut” into this revolving disc, as if a corkscrew had removed the cap that covers Otello’s claustrophobic world. The three scenes (Beach, Hall, Bedroom) are, each within itself, realistic, but they are not realistic with regard to their architectural relationship: the windows of the Hall open to the Beach level (improbable in a fortress); the main entrance of the Castle, from the Beach to the Hall, directly connects the outside with the private rooms instead of with a courtyard; and so on. This is done in order to maintain continuity of action, moving the “view” from one environment to another, even within the same act, depending on what's called for in the libretto. The audience will have the impression of the proscenium being the frame of a camera whose lens is the eye of the individual spectator, with the camera following the work around the “zone of action”, this last one limited to the revolving plate. Only Iago, the “puppeteer”, has the chance to “exist” outside of this world, stepping out of it to directly address the audience: the “host of the Devil” has no need to see the “world of humans” behind him to know what’s going on… COSTUMES The costumes have been designed mixing the late Medieval fashion with the early Baroque one. Cyprus was a “crossing point", a port at which to stop for provisions and business (hence the commercial interest that fueled the large number of wars fought over possession of the island), and, in consequence, a land of multiracial characteristics. It was nothing unusual to see the most varied types of outfits in Cyprus, and the interaction between cultures and religions was, thanks to the common god, “money”, less conflicted than we might imagine. Nothing new under the sun…

|

|

Director's Concept

|

Singing in the Service of the Character Cantabile Cecilia Scalisi July / August 2013

Cecilia Scalisi: What was the process by which you discovered your role as a stage director? José Cura: My singing career has always been distinguished by a tendency to interpret, to act, to use singing as a tool in the service of the character and not the other way around, with the character at the service of singing. This choice in my career led me towards a course that attracted the attention of many, positively and not so much. CS: In what way could it have caused a negative impression, since opera demands more and more preparation and acting commitment from singers? JC: When one presents a new product (because in the contemporary market we speak of a “commercial product”), there are people who embrace it because it excite them and others who prefer to repeat the same old product without experiencing change. Both positions are valid. CS: What is your definition of “singing at the service of the character”? JC: It implies that sometimes I have to sacrifice vocal beauty because I judge the character to be suffering a certain issue in that moment and it isn’t believable for the voice to sound too lovely. For example, I sing the ending of Otello with a small voice, with a broken voice. I see no other way to interpret the death of a person suffocating in his own blood because he has just plunged a knife into his gut. That is my vision of the character and I can’t see any other way to interpret his end. CS: Going back to the stage direction ... JC: It was the result of a personal search to find the balance between the dramatic effect and the song itself. In 2007 I received a proposal from a Croatian Theater whose director was interested in my approach to acting. She thought it would be interesting for me to do the complete staging of a show I would also devised. That show was called La commedia è finita. The project ignited a flame I hadn’t anticipated. In 2008 I was invited by the Cologne opera, then by the Karlsruhe opera (both in Germany) and I have been directing for six years now. CS: With your accumulated experience in singing and now in stage direction, how do you judge the work of other régisseurs? JC: If you are playing a character who you have already mastered, the shortcomings of the director are not so serious if he lacks direction, because in a way the singer can save himself. The problem is when the directions he gives are wrong. I have come across régisseurs who do not really know what the text of the opera says, since they are directing from a translation. That’s serious: for a stage director to direct a work whose text he cannot read or understand in its original language ... That is the worst! CS: I have always heard you put the emphasis on singing only what you have mastered idiomatically, as well as not singing phonetically. JC: That's right. In the past, opera was characterized, in 99% of productions, as a parade of costumes and sets. The dramatic juice of the libretto mattered little, to such an extent that there were singers who didn’t even know what their companions were saying in the same scene, people who only knew what they were supposed to sing, and perhaps in duets they knew more or less what the other was saying. That does not happen in the theater or in the cinema ... It is a revolution that has yet to reach the opera. CS: What would be the changes that this “revolution” should bring about? JC: That the artist sits in front of his libretto and sees what there is besides from the notes, the highs and the beautiful moments. In many letters Verdi asked that for certain characters the voices should not be "pretty." In Otello, for example, he said "the only one who sings is Desdemona. Otello has to bark." He was already looking for that modernity. We, after so many years, are trying to embrace that and continue the search initiated by the composer. However, push back continues. CS: Do you think opera audiences prefer to see a repetition of what they already know or do they want to take the risk of a “theatrical interpretation”? JC: It’s one thing to recreate and another to interpret a work. When you recreate what someone else has already done, that's it ... it's over. But when the work is interpreted, the artist plunges right in and tries to say what he thinks he has to say. That’s the reason people keep going to hear the same opera over and over again, because if all we did was copy what has already been done, nothing would make sense. Myself, if I were a member of the audience and knew I was going to see the umpteenth Otello that would look just like the last one and the one before that, because “this is how it has to be,” I wouldn’t be interested. I think if we continue in that direction we will definitely lose the audience that must be won for opera. Besides, I consider that in art, change and search is a fundamental approach. Sometimes you find what you are looking for; sometimes you don’t. But it is essential for artists to be in a constant search. In fact, I consider it an obligation. Otello: twenty years of searching. CS: What do you have to say about Verdi's Otello? JC: I've always done other people's Otellos. Sometimes they have been successful stagings and sometimes not so much. People have to understand that when an artist goes on stage he is not only offering his own stuff but also following the interpretive line of the régisseur, which may not always align with how the artist feels. Once, a director came up with the idea that Otello should go out bare-chested and there are still people who think that all the Otellos I have sung—in thirty years of opera!—have always been sung bare-chested. CS: What will your Otello look like? JC: The look will be medieval, as close as possible to what we know from the books. I want to show an Otello located more or less in the historical period in which it takes place: halfway between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Shakespeare does not specify which of the battles between Turks and Christians he is talking about, so I, for an emotional reason, thought of placing it in the Battle of Lepanto, year 1571. CS: Finally, after so many years and productions of this opera, what is your conception of the character of Otello from the vocal point of view? JC: Except for Desdemona, who sings in a melodic "bel canto" mode (this is in quotation marks because Verdi himself said that he wrote melodramma), all the other characters in Otello base their vocal structure on a type of singing that is more declamatory than melodic, more sung on the word and on the repeated note. I sing the character as I understand it and I feel that he has to be sung. I claim my right as an artist to show the way in which I conceive the work and ask those who see it, whether or not they agree with me, to recognize the work behind it, the study and the sacrifice of twenty years of research behind the character.

|

||||

|

Otello, According to Jose Cura: Far from Realism and Hysteria Clarin Sandra de La Fuente 18 July 2013

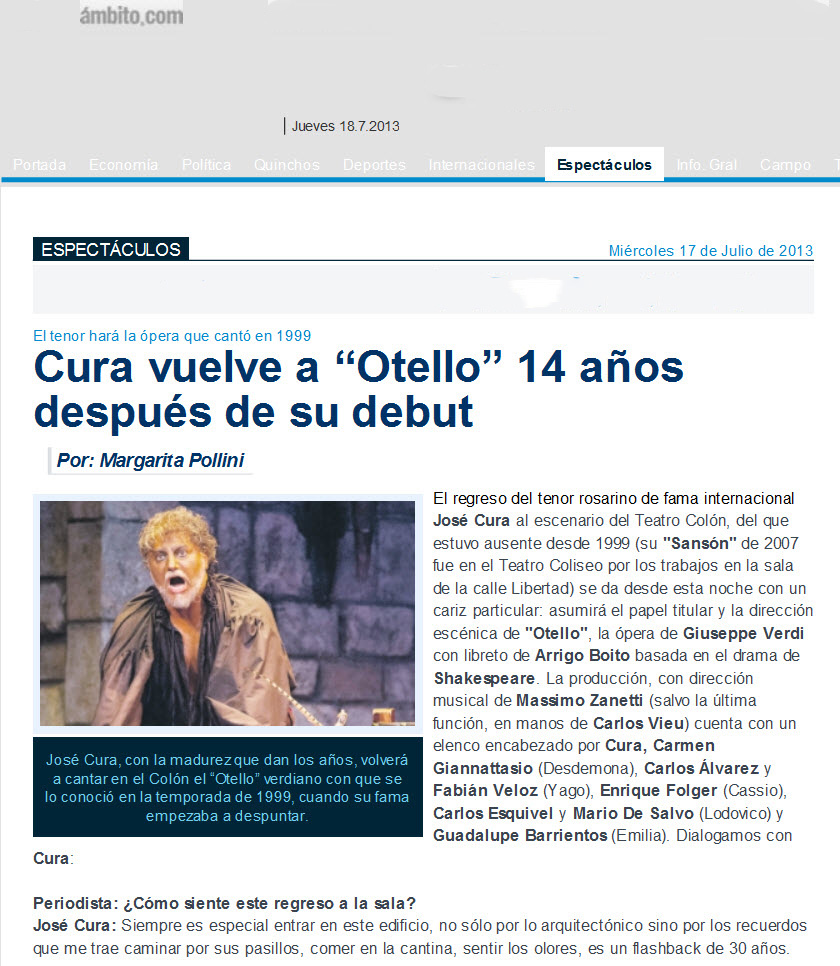

“To enter the Colon today is like facing the fresco of the Sistine Chapel. Of course, when you start working and move into the guts of the theater, you see all that is still missing,” assessed Argentine tenor Jose Cura a few days before the premiere of Otello for which he functions in the dual role of actor and stage director. Born in Rosario in 1962 and based in Madrid for the last 15 years, José Cura is one of the most famous tenors in the world, and a much sought-after Otello in theatres around the world (he previously performed it in the Colon in 1999). “In 2001, for the centenary of Verdi’s death, this role took me everywhere. Now for the 200th birthday, I’m back to traveling: I came from the Metropolitan Opera and after my dual assignment in Buenos Aires, I go to Vienna and Berlin,” he says. Q. You say things are missing in the theater. What things? JC: There are missing sections, office areas, certain things need to be made operative, the workshops need to return to the theater. I do not know the reason why these things are missing, but, yes, I know they are missing. The theater is not an island. It is the social reality of the country and all the emotional, social, economic and political upheavals affect it. However, the people who work here suffer to keep the theater open. For example, I found a carpenter who promised to make me a chair I needed. And he did, and the chair is perfect. I understand that he makes that chair as his contribution so that the theater works. This happens at all levels and it is this that saves the Colon. Q. Some directors complain about the disorder that is in the theater. JC: It is that disorder creates stress. And when one has to work at the pace I work at, unnecessary stress is negative. It so happens that here are my genes, my roots, my people so my ability to adapt is faster than that of a German or Englishman. I know that you have to work with your left hand, as the Spanish say. Q. What does that mean? JC: In boxing the right hand is the one that knocks out and the left is the one that checks. You have to use the right hand when needed, because every so often there is a need to strike a blow so the house does not fall but one always works with the left hand. Because you have to get people to dream your dream and not turn into puppets in your dream. Ours is a business, we make money here, but we often forget that it is a business based on a vocation, in a system whose raison d’etre is the energy exchange between individuals. If that is missing, the work rots. The leader’s job is to motivate, to touch this little button that remember the vocation. I am trying to make the entire theater breathe with enthusiasm. I am not going to eliminate problems but we can return home feeling we had a beautiful day. It is important to know where you want to go with a project but also to listen to the voices of the people with whom you work. Feedback will lift the project. Authoritarianism always leads to failure. Q: Does your method work here? JC: Yes, and very quickly. The other day, the choir gave me a demonstration of affection that moved me to the bone because the rehearsal went overtime but no one moved from his place, no one complained. They continued working until we got the scene right. That happened because there was an energy that no one would have thought to interrupt. Now, a director should be careful and not take advantage of it. It is necessary to earn the love. Q: It doesn’t seem simple to overlay the director’s role with that of the protagonist in the opera. How did you manage it? JC: It requires an enormous energy and the ability to see yourself. It’s also necessary to have a team of reliable professionals. I call them my ‘rear-view mirrors.” An assistant director is your eyes, as long as you have real confidence in him and he is part of the process from the beginning of the project. I discuss, but I believe what they tell me. Arrogance in the leader of the work is useless. Besides, I have Fernando Chalabe, my friend since I entered the theater thirty years ago. He replaced me in the role of Otello so I can see the movement from the outside. Q. Otello has been played by singers who have left a strong mark in history. Do you take anything from them? JC: Yes. Domingo, del Monaco, Vinay—also like our, like Cosutta—they marked the passage of time and were great Otellos in their time. For del Monaco, he was called to be Otello in the postwar period, a special time in which society needed to say it was still alive. Domingo did his Otello at a time when the fundamentalism that today invades the world was not so evident. And when I speak of fundamentalism, I do not speak of turbans and camel, but of someone who wants to impose his ideas on those of others, even if you dress with suit and tie. To interpret Otello today, in light of the international situation, with the fundamentalism that has so exacerbated since 2001 is another thing. Q. Are you announcing some sort of update in the staging? JC: No update but an awareness of what it means to be an apostate and traitor. This is the Otello of Shakespeare but today it takes on a different significance. I don’t need to modernize to make it clear. Although I think Otello could be done with minimal staging, because the force of the words is such that they tolerate everything. In this staging there is a compromise: we use the Black Box and we exist inside the turntable of the theater, which is great because it is 20 meters, allowing me to mount all the scenes and maintain a continuity, the famous continuity that Shakespeare sought. Inside the turntable, everything happens and outside the turntable only Iago exists because it is he who interacts with the audience. That means the production is not 100% realistic or 100% hysterical. Q. You said ‘hysterical’? JC: Yes, ‘hysterical’ because some force everything. I had to do Otello in a spaceship. You can imagine the absurdity of the situation: I looked like Captain Kirk and Iago was Spock. Absolute banality.

|

||||

|

|

|

|

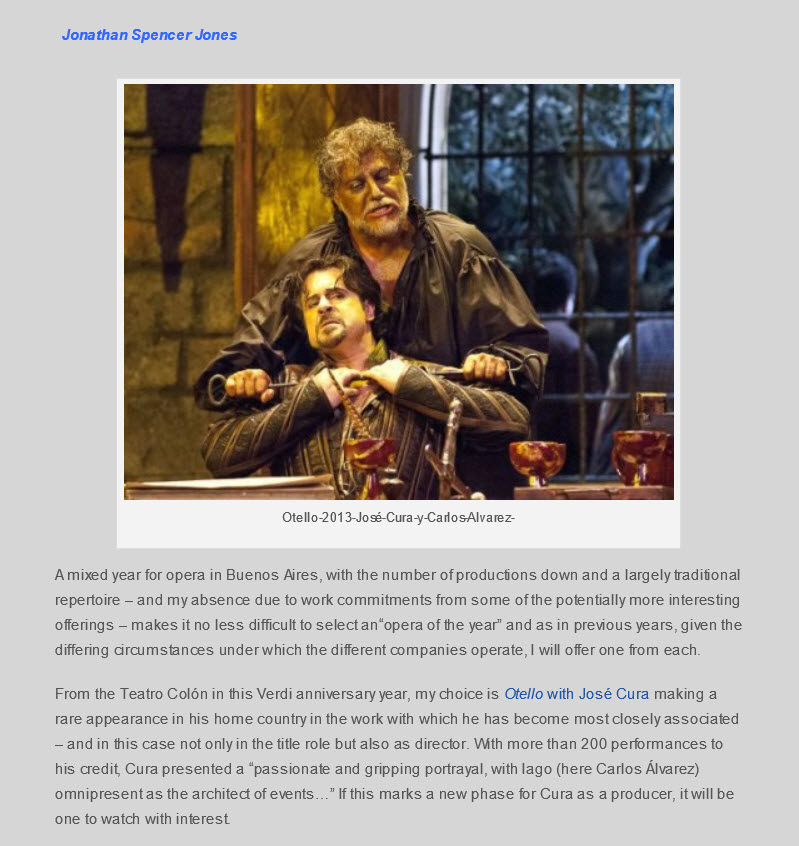

Love, Jealousy, Passion La Nacion Jorge Araoz Badí 18 July 2013

The Teatro Colón reveals a new version of Verdi’s famous opera, with José Cura starring in many roles A rehearsal of the version of Verdi's Otello, which will return to the Colón tonight after a 14-year absence, hardly resembles any other rehearsal of the same opera or of any other in the classical or romantic repertoire. It is not that the procedures, practices, method or rituals are altered. As opera rehearsals move forward, they always boast the presence of the protagonist, the stage director, and possibly the set designer. So it is with this Otello 2013, but here the circumstances are totally outside the norm, for the three most fundamental, decisive, and significant roles of the opera are held by a single individual. If one did not see the work of the Argentine José Cura in the rehearsal and finished product, it would be difficult to understand that the three tasks that are so differentiated and important, which are always in the care of so many specialists, can be monopolized by a single director and managed by nothing more than the mind. It is curious and unsettling to be in front of the singer who rehearses his part and at the same time warns that the window does not close well and gives an instruction to an artist who accompanies him on stage and makes a point to the conductor, and then leaves everything to make a surprise leap from the stage into the stalls to speak with the time keeper. Everything at once, without pause. Is it possible? Apparently, it is. Dramatic concentration La Nacion watched the end of the second act. Although every moment of Otello is essential, this act contains the overview of the psychological intrigue. It has the famous Credo (Credo in un dio Crudel) of Iago and all the weight of his perversity fired on Otello, which generates the tremendous climate of tension. Consider the actions of Iago and in this case, the performance of baritone Carlos Alvarez (who arrives from Valencia where he had performed the role, who seems in good vocal condition and whose acting style is very communicative) to support this review. However, Cura’s Otello, who sits listening to the deployment of inventions concocted by Iago and barely moves a few muscles in his face and even those perhaps unintentionally, dominates the scene and produces a memorable theatrical tension that grows without pause until his disheartened outbreak. His is such a strong personality that he needs no easy recourse to thrill. How would you describe your set? JC: As a search for the Shakespearean continuum. The scenes, the seamless actions are intended to let people see the opera as if it were a movie. It has the characteristic of Brechtian [theater], in the sense that it is a play within a play. Do you have experience as a stage manager? JC: This is my seventh. Samson et Dalila has already been recorded. Although, really, not all experiences in all theatres are equal. Luckily, here in the Colón I have found collaboration on all levels and very positive affection and understanding. As for the cast, I think it is of the highest quality, but that will be seen as of tonight. The ending is known to all, so there is nothing to reveal. But does your concept have any relationship with the Otello you performed here in 1999? JC: In 1999 it was run by a different director. Here the focus is mine. Futhermore, in ’99 I was a boy who played the drama as an elderly man. The pains of life I knew only as they were told to me. Now, at the age of fifty, I know them because I have lived them. It is another vision. And the movement of the action matters a great deal? It’s very fluid. The idea is if we turned off the music, everything has to work well theatrically. To end, what does the voice that is heard relate? JC: Otello comes from a battle. Shakespeare does not say which one. So I imagined it as the battle of Lepanto. Miguel de Cervantes, the author of Don Quixote, fought there. There is a curious coincidence between Cervantes and Shakespeare. The two great geniuses of Spanish and English died in the same year. Cervantes recounts the battle of Lepanto as ‘that great epic.” Shakespeare alludes to a war. From these things, I put together a brief comment from Cervantes, read by a reporter, to emphasize a bit on the historical and human brotherhood.

|

||||

The tenor sang the opera in 1999 Cura Returns to Otello 14 Years after his Debut Ambito July 2013 Margarita Pollini

The return of the internationally renowned Rosario tenor José Cura to the stage of the Teatro Colón, from which he has been absent since 1999 (his Samson in 2007 was performed at the Coliseum on Liberty Street) will give tonight’s premiere a special look: he has assumed the title role and is stage director of Otello, Giuseppe Verdi’s opera with libretto by Arrigo Boito based on Shakespeare’s drama. The production, with musical direction by Massimo Zanetti (except for the last performance which will be conducted by Carlos Vieu) features a cast led by Cura, Carmen Giannattasio (Desdemona) Carlos Alvarez and Fabian Veloz (Iago), Henry Folger (Cassio) Carlos Esquivel and Mario De Salvo (Lodovico) and Guadalupe Barrientos (Emilia). We talked to Cura: Q: How do you feel about returning to this space? JC: It’s always special to enter this building, not only for the architecture but also the memories it brings to walk through the halls, eat in the canteen, smell the odors. It’s a flashback from 30 years ago. Q: Are the memories from your first time on stage positive or negative? JC: There is everything: positive and negative. The negatives, now that I’m older, are set aside, because they were the ones that convinced me to take the plunge, and perhaps by not having living those bad experiences, I would not have gone and done what I did. And among the good, I started my career here. Q: What is your perception of the climate in Argentina since returning after an absence of several years? JC: I don’t like to talk much about it because when you get into politics you are always injured and bruised. I will only say that people seem a little sadder than before. My memories of 30 years ago were of very elegant Argentines walking down the street, always well dressed, and now I see people neglected not by personal neglect but as a reflection of a situation. But I cannot go further because I don’t know the profound reality. I know that there have been many good things done and others still left to do, and I play here on the premise of my affections but I do not live here and what I know I learn from the newspapers and that depends on what is read and how things are one way or another. I do not want to delve into the reason because I don’t know, but my perception is that of a town that just a little bit beaten down. Q: You live in Spain, which is going through a great economic and social crisis. How do you see its repercussions on culture in Spain and Europe? JC: Inevitably, when there is an economic crisis one of the first things to be affected is culture, right or wrong. In the short term, if you have to choose between putting food on the table for the children or going to the theater, the answer is obvious and you have to start trimming the extras. Entertainment, although a fundamental part of the structure of society, does not stop being something added-on and when one can afford to amuse himself he will and when he can’t he remains at home. But the next generation pays for the cut in culture, and then the remedy is much more complex. A people without culture, without identify, without roots, drifts. Whenever you want to undermine the foundation of a society, attack the culture. Q: Why did you choose to return with Otello, an opera you sang here in 1999? JC: I did not choose. I was invited to create a Verdi opera in the year of Verdi, and when you talk about commemorating you pick is the one with which one is most identified within that author's oeuvre. Otello is the opera that I am doing in some of the most important theaters in the world, and it was also the opportunity to do the opera as I always wanted to see it. The thing we did in ‘99 was for me a “coitus interruptus.” I did not have the maturity that I now have, not only in age but in the 150 or 200 performances of the role that I have since sung. When you’re young the only pains in life you know are those of which you are told, then you lives through them. All this affects the character, especially Otello, a man my age who feels the weight of life on his head. There was also a time when there was a lot of hype around me, much more than I could handle. It is a process through which everyone who is of a certain level of “product” or celebrity is almost obliged to pass. Many do not make it, it is a process of natural selection, but those of us who do, who endure and survive, we have the advantage of another stage, the real one, when you can concentrate on making art, which is what I’m living now. Q: What is the main conflict of Otello? JC: There is not just one. If there were, it would be easy but the work would not have the effect it has. The play was written around 1500 by Cinzio, which inspired Shakespeare and Rossini and reached Verdi through Boito. There is still debate about the themes and no one can tell how Otello should be. You have to choose a path for yourself. Mine is the face of a personal quest that is not dogmatic but it is what I find comfortable in my understanding of the drama, and that is to be recreating the life of a person leaving his original religion, a Muslim who becomes a Christian and makes a career being hired to kill Muslims, so add treason to his apostasy, the fact he abandoned his religion for convenience. In light of the facts of the beginning of this millennium driven by all kinds of fundamentalism, not only Arabic, that are almost one of the economic engines of civilization, the character of Otello has a much more dense and current psychological profile. Q: How do you approach the visuals? JC: It is almost an exercise is Brechtian epic theater. Our set is not located in the real world but in a black box and a rotating stage so that everything always flows without interruption. The environments themselves are realistic but not in their relationship. Q: Overall, what is your relation to the impact generated by your work by the audience and the critics? JC: When I was younger I had problems but then I realized that there is no way to conform to everyone. So you have to believe in what you do. If you are liked by everyone it is because you have nothing new to offer, and if you are disliked by everyone it is because what you do is done badly. It no longer matters what an artist does not, only respect: you don’t have to agree with an artist but recognize and respect his path, his career, his inquiry. With education you can go anywhere. A lack of education is what is hurting us. All those negative comments which are generated in the social media cause more damage to those who make them then those who receive them. We should channel that energy into doing something positive.

|

||||

|

|

The Successful Tenor Feels like a Foreigner in his Homeland Perfil 14 July 2013 Based in Spain for over two decades, the singer will present Otello at the Teatro Colón. He says its restoration was impressive José Cura, the great Argentinean tenor who has lived in Spain since 1991[sic] and is a figure on the international opera stage, is in Buenos Aires. The audience will have double the opportunity to experience him. He will perform the role of Otello, based on Shakespeare’s tragedy and set to the music of Verdi, in a role that has brought him endless acclaim. In addition, he will be the stage director and set designer for the production. Performances will take place from 18 to 31 July at the Teatro Colón, where he trained in 1983 and where he now declares he is returning with full satisfaction. Cura is a versatile artist for music lovers, some of whom do not forgive him—while others are fascinated by—his ability to perform several tasks at once: singer, director, conductor, producer of shows. “In the theater this happens often, in cinema as well. People are surprised that I can do it in opera. It requires a great capacity for sacrifice and the ability to absorb fatigue, because the work is multiplied by a thousand,” he says. Q: What can you tell us about this Otello? JC: The most important thing about the staging is the almost cinematographic continuity of the actions, of the scenic gesture. In general, in the Shakespearean theater, characters come and go without interruption but that is hard to do in the opera house because the curtain is lowered to allow the scene to change. But the Colón has a giant turntable. I think it is the largest in the world, at least in traditional theaters. It measures twenty meters in diameter, almost the size of the entire stage in many European theaters. Taking advantage of this turntable, we don’t have to stop to change scenes so the (dramatic) thread is not lost. The stage is a Brechtian epic theater, a little attenuated: what happens inside the turntable is not reality, but around it, people can see that it is part of a theater. I want the machines, the lights to be seen. It is a declared intention of making theatre within theatre. Q: Could this be mounted outside the Colón? JC: I’m going to confess something: four or five theaters in the world have already asked me to do this staging but all the ones I’ve sent the plan to have told me that it does not fit. Not all theaters have turntables and even those who do have modest rotation, about ten meters. Q. How do you perceive the Colón on your return? JC: I have a strong sense of time travel, but not to the year 1983 but to 1908, when the theater opened for the first time. I found a theatre whose face I did not know, with brightness, color, beauty, presence…The cleaning and restoration that have been made are impressive. Regarding work stoppage and criticism of the renovation, these are things I read in the newspaper and I will not dare to make a comment because I would be speaking through the mouth of an outsider. Q: How do you see this Argentina with respect to the 1980s? And how do you see Spain today? JC: It is not possible to compare times so abysmally different. The year 83 was the first year of our renewed democracy. Now we have thirty years of democracy: more or less beaten up, depending from what point of view you look, but this is our democracy As much as my roots are here, my loves, I am still a foreigner in my motherland so I don’t live daily reality. And about Spain, there is the global crisis. Unfortunately, this is a globalized world. But the thing is that the economic crisis, from my point of view, is the result and not the cause. The cause is a crisis of morals and values.

|

||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Program

|

|

Bravo Cura Goes to the Opera

Act II

For the famous Credo, Cura grants Iago the power over time so that when he claps his hands, Cassio freezes in place. Cura accents Iago’s extra-ordinary abilities by having Iago bend over the open-pit fire as the flames change from orange to ghoulish red as if the ensign controls the hell below. At his order the turntable begins to rotate as he sings his famous paean to the nothingness of man, first displaying Otello surrounded by his staff and hard at work in his office and then a giddy Desdemona dressing with the help of Emilia in the bedroom. Interestingly, Cura has Iago keep his eyes closed throughout, inserting the question as to whether Iago is controlling the action or simply has the ability to see beyond what is apparent.

Cura’s genius in setting the stage on a rotating platform to enhance the flow of the story is now made evident. Cassio and Desdemona meet in the courtyard while Iago and Otello attend to work inside the fort—but the two environments are linked by door and windows. It also allows for a lovely choreography of movement between the two domains, as when Desdemona comes to the window and presses her hand into Otello’s—a magic moment of great sensitivity.

Another wonderful insight comes when Cura has Rodrigo, a rich man besotted with Desdemona, arrange the flowers and children chorus as a tribute to his affection for her; the continuity marries nicely with the opportunity to use a character who too often exists only on the periphery of the tale.

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|||||

|

***

In 1993, he had his first starring role and the following year, with the trophy from Placido Domingo’s Operalia, he jumped to the front page of the media. Everything accelerated. 1995: he made his debut in London (Covent Garden) and Paris (Bastille). Later, two of the iconic roles that positioned him among the best in the world: Samson in London and a triumphant Otello with Claudio Abbado in the Regio in Turin. It was then that Arena di Verona summoned him to replace José Carreras in Carmen at the last moment and he made his debut with glory in the Italian Amphitheater. “I wanted to greet the clerk who had told me there, in 1991, that I could only sing if they hired me as a soloist, but he was gone,” he jokes. In 1999 he become only the second tenor in Met history (after Enrico Caruso in 1902) to make his debut in the opening of the season, and in 2000 sang Traviata a Paris that was transmitted around the world. In the same year, standing on a summit at which few arrive, he decided to kick the board, challenging the system of managers and record companies, breaking the rules of the classical music business. He wanted to manage his life and it was hard for them to forgive him. “At the moment I thought to take advantage of my image and position to try a new way: create my own company and manage my career. I had not spent years studying to remain just a picture of a handsome fellow. I needed challenges and I was right. Now I consider myself a mature artist but it took me years of beatings and bad press.” The Price of Image By the mid-1990s, his record label had transformed him into a Latin lover, a sort of operatic Sandro who was a hit in record sales and concerts, signing autographs for female audiences who adored him like a rock star. “They sold me as a sex symbol and that was part of the game, but I got tired of it. Cura is a handsome guy but in a few years he will fall, they said. And this was only the 15 minutes of fame. You cannot bet everything on that one horse that is nothing more than an ephemeral and trivial chapter. I paid the price of rising fast at the expense of the image, passed the filter of time and here I am: 25 years in a career that shows there was something else behind the façade.” [Note: Roberto Julio Sánchez (August 19, 1945 – January 4, 2010), better known by his artist name Sandro was a notable Argentine singer and actor. He is considered one of the first rock artists to sing in Spanish in Latin America. Sandro was also the first Latin American artist to sing at Madison Square Garden, in 1970] Why did he allow himself the luxury of renouncing that of which everyone dreams? Was it the whim of a divo in the moment? No, he answers emphatically. Quite the contrary. He did it for his independence, for liberation, to grow as an artist and find a meaning beyond appearances. And yet, in contrast, he says the opera divo no longer exists, there are only singers with personality and charisma, and fans who live longing for memories of times past, imagining that maybe someone will emerge to revive the fascination of those stories that represent a longing for a different life. “That’s the folklore of the genre,” he says. “Callas, with all her artistic genius, ended her life in great tragedy. People think it’s pure glamour…It’s only that when someone is making money off of your image … but most of the time, we end up alone in our hotel room, zapping and eating something from room service. The loneliness is overwhelming…” But his ability to work enthusiastically and passionately allowed him to transform those occupational hazards into strength to make the most of his time. What he does escape, however, is the routine into which many in the profession can fall, the boredom and repetition of endlessly singing the same work in the same house until exhausted. “When you have the energy that I have, the conviction and the restlessness, the training and experience, many people become frightened because they feel my attitude shakes their little homes. For some, routine represents security. For me, it is the beginning of death.” And while he admits he never imagined he would get to where he did based on where he came from, he believed in music as a faith and his own rebelliousness as a manifesto. “Sometimes I look back and I begin to recall memories, see myself 25 years ago and ask myself, with a mixture of pride and nostalgia, how did I get here? I’ve changed a lot since then. Life is no longer what they tell me it is but what I can begin to tell myself,” he reflects. However, in the deepest recesses of his being, he did know that the indomitable spirit that still animates him would guide him, against all odds, to any summit he might aspire to. And so he charged, fearlessly, into the world of opera, with the blind and unstoppable force of Samson at the millwheel, demolishing with his steps the cracked walls of custom and indifference. The Return to the Teatro Colón Faithful to his style and against the must stultified musical criticism, José Cura defends the interpretation of strong personal concepts. “The imitation of the past is decadent. What would history be without the revolt of the artist!” And he proposes—as a stage director and set designer—a medieval aesthetic tone for the new Otello which premiered Thursday at the Colon. The setting, located in the Battle of Lepanto (1571) is his version after decades studying the tragedy of the Moor of Venice, one of the most legendary and successful characters in his career. “Before I had to paint my hair gray to look older. Now I have to cover it not to look too much so. In the arc of time lived, all humans change.” With musical direction of Massimo Zanetti and stage direction from the same José Cura who will star in the play (Otello), there will be four new performance in the Colón: tonight and on 24, 27 and 30 of this month.

Something Very Personal

*The Letter from the School (1970)

Saint Patrick’s

College

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

Successful Production of Jose Cura of Giuseppe Verdi’s Otello Cienradios Pablo Fiorentini 26 July 2013 On Wednesday, 24 July 2013, the Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires presented the third performance of Otello by Giuseppe Verdi with Rosario tenor José Cura in the title role and as director. The show began with a narration by way of prologue in which Miguel de Cervantes expresses his impressions of the Battle of Lepanto, from which the director took the battle from which Otello has just returned victorious. This introduction alters the work without complementing it, not only because if provides the audience with unnecessary data, but because it mitigates the drama of the opening scene of the storm and the providential arrival of Otello, one of the strongest moments in the opera. Nevertheless, we must applaud the staging of Jose Cura, based on three stage sets, mounted on the revolving stage, representing an exterior courtyard, the main hall of the palace, and the bedroom of the leading couple, which were rotated on the wooden platform with such precision that every scene occurs in the right place, creating an almost cinematographic framework. An example of this was seen at the end of the third act when Otello—totally driven mad—is lying on the floor of the courtyard but rises up at the beginning of the fourth act and steps towards the main room while the stage rotates, there to sit in a chair to meditate, then with a new turn of the stage to go to the conjugal bedroom where he murders his wife Regarding the performance of the singers, we can say that the tenor Jose Cura had a very good performance, demonstrating possession of a wide palette of tones and colors used to construct a more melancholic than alienated Otello; for her part, the Italian soprano Carmen Giannattasio composed a psychologically mature and vocally accurate Desdemona, distinguished by her poignant lyricism and expressiveness; and finally we must mention the very good performance by the Spanish baritone Carlos Alvarez who creates an Iago who is more strategic than demonic….. The rest of the cast performed at a high level, especially Enrique Folger (Cassio), Guadalupe Barrientos (Emilia) and Fernando Chalabe (Roderigo); correct performances were provided Mario De Salvo (Montano) and Fernando Grassi (Herald). The orchestra had a solid performance, despite the low intensity from director Massimo Zanetti who contributed little to the vision. It was perhaps the lack of musical emotion in this Otello that held the audience silent during the performance, exception for the applause for Carmen Giannatsio at the end of the Willow Song. A final, warm recognition was awarded to each of the singers.

|

||||

|

|

|||||

|

Otello Opera Club Roberto Falcone 23 July 2013 [Excerpt] The responsibilities of stage direction and staging were added to that of the performance of José Cura as the lead in this opera. It was a daunting task for a singer who already has enough to do with a difficult vocal and acting role without having to add other responsibilities. As a regiseur, Cura showed us an Otello within the tradition (thank you!), with some very interesting details, such as the denouement of the opera, with the death of Emilia and Iago, and Otello's gesture to Montano, Cassio and Ludovico to leave the room and let him die "intimately" with Desdemona and in the presence of his disloyal ensign. The staging was suitable for his purposes, with a simple setting consistent with Cura's conception of the work, as evidenced from what he wrote, and we could read, in the program’s hand bill. Clearly José Cura is not a “conventional” tenor from a vocal perspective; he is unique in his phrasing, in his singing style and in his technique, Cura needs no introduction after so many years of career, nor considering how controversial he has and continues to be over its course. As with many singers, audiences around the world are divided between supporters and detractors. The same is true at the Colon. It may be appropriate here to apply to Cura Iago's response to Ludovico regarding Otello: “È quel ch'egli è.” [“He is what he is.”] Perhaps to understand him best it is necessary to see him on stage rather than listen to him on recordings. While always maintaining that conceptual consistency of the character of Otello, Cura did have some touching phrases, worthy of the greats, and a truly moving ending to the opera. Soprano Carmen Giannatasio's debut was a pleasant surprise. She brought with her a beautiful voice, excellent emission, and lovely stage presence, everything necessary to fulfill her commitment very well. The baritone Carlos Álvarez showed his handsome voice and his stage experience in the role of Iago, despite some moments that were not well resolved during the “Credo.” He is undoubtedly a singer of distinction. The secondary roles were covered adequately with the new breed of young singers from our theater: Enrique Folger, Guadalupe Barrientos, Mario de Salvo and Fernando Grassi. The same goes for Carlos Esquivel, the Argentine bass who is making a career in Europe, and Fernando Chalabe, the most veteran of the Colon singers in this performance, and who always stands out with his professionalism and dedication. What happened with the Orquesta Estable was absolutely bizarre. Knowing the satisfactory performance of this body throughout recent seasons, the many imperfections heard was inexplicable: mismatches in the nuances of the first act love duet, some fake and false notes, imbalances between orchestra and stage. Were all of these the fault of the conductor? Perhaps not all of them, but on the other hand, Massimo Zanetti is no more than an adequate conductor, apparently with difficulty in achieving a neat orchestral execution of his ideas. We have heard better Otellos from the CoroEstable. In short: a successful performance of Verdi’s Otello but one which will be colored by expectations and degree of admiration for the star.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

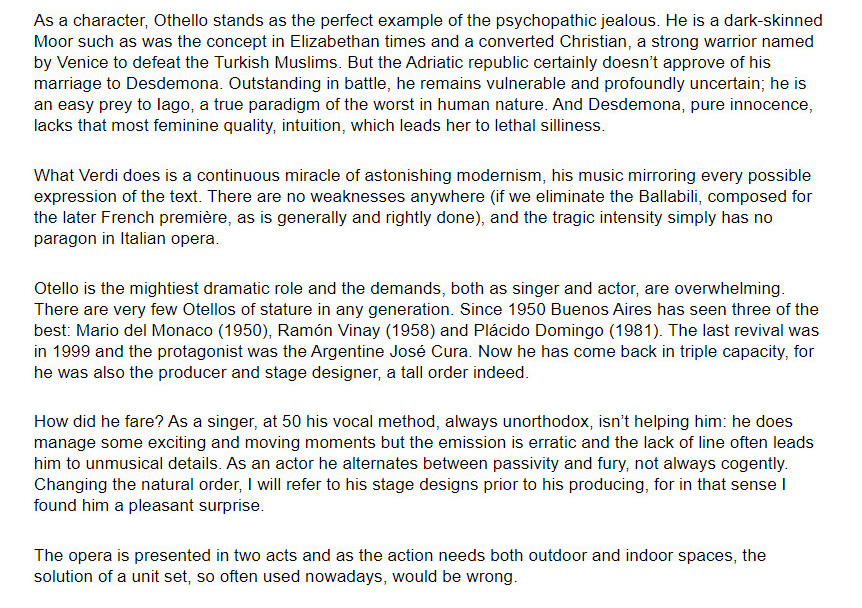

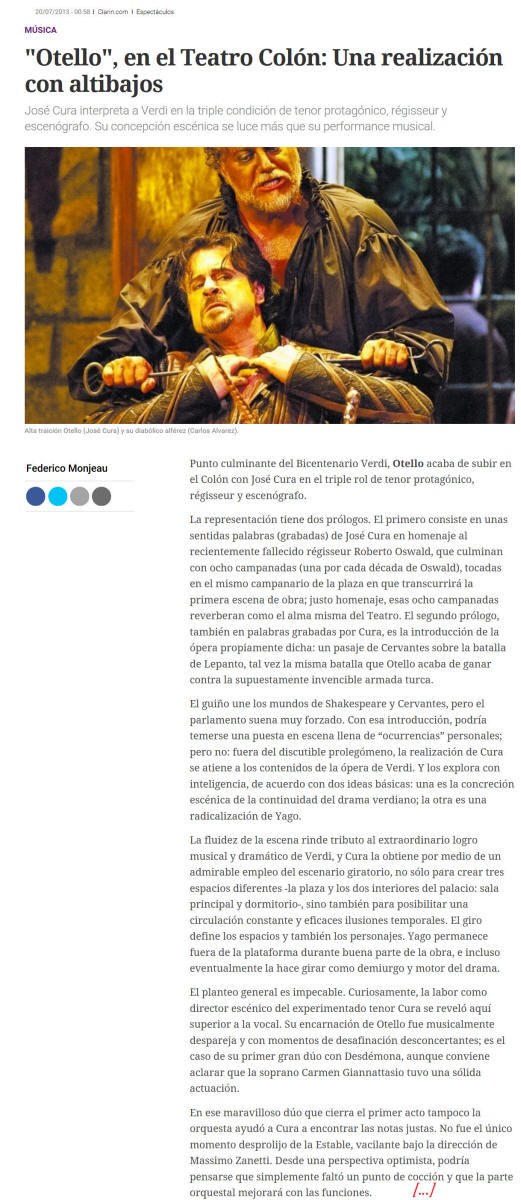

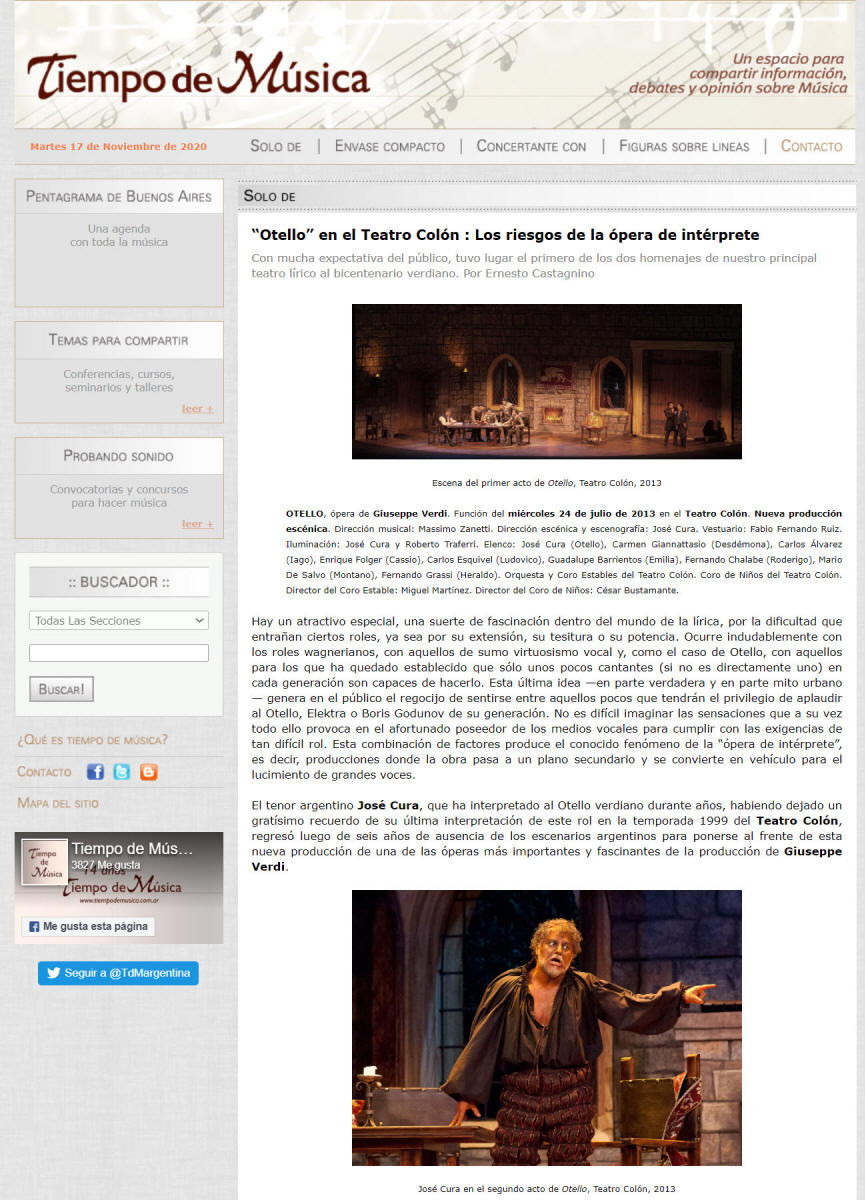

Otello at the Teatro Colón: The risks of the interpreter's opera

With much expectation from the public, the first of the two tributes of our main lyrical theater to the Verdian bicentennial took place.

Tiempo de Musica Ernesto Castagnino 24 July 2013

[Excerpt] There is a special attraction, a sort of fascination within the world of opera, for the difficulty that certain roles entail, either because of their length, their tessitura or their power. It happens undoubtedly with Wagnerian roles, with those requiring extreme vocal virtuosity and, as in the case of Otello, with those for which it has been established that only a few singers (if not just a single one) in each generation are capable of doing it. This last idea - partly true and partly urban myth - generates in the audience the exhilaration of feeling among those few who will have the privilege of applauding the Otello, Elektra or Boris Godunov of their generation. It is not difficult to imagine the sensations that all this in turn provokes in the fortunate possessor of the vocal means to fulfill the demands of such a difficult role. This combination of factors produces the well-known phenomenon of the "performer's opera," that is to say, productions where the work is secondary and becomes a vehicle for the showcasing of great voices. The Argentinean tenor José Cura, who has performed Verdi's Otello for years and left a very gratifying memory of his last interpretation of this role in the 1999 season of the Teatro Colón, returned after six years of absence to take the lead in this new production of one of the most important and fascinating operas of Giuseppe Verdi's compositions. From the cover of the handbill a large photo of Cura as Otello invites us to think that this will be a "performer's opera": no title in recent seasons has merited a photo of its star on the cover of the handbill. When we open it, we find the tenor's name in four roles: stage director, set design, lighting design and lead. We continue reading and four pages appear under the title Notes from the stage director where José Cura explains his intentions for and visions of the work and the character. We close the program and when the lights go out we hear over the loudspeaker: "Good evening, this is José Cura...". It’s confirmed, we are in the presence of a "performer's opera." The production concept had both strengths and weaknesses. The use of the revolving platform to divide the stage into three interconnected sections and allow, as it rotated, the singers to move from one space to another, created a continuum between many scenes that gained in dramatic fluidity. It is also true that, after a certain point, the mechanism produced visual exhaustion and became less effective. The attempt to seek historical realism by framing the fiction created by William Shakespeare and recreated by Verdi and Arrigo Boito in the context of the Battle of Lepanto contributed little to the opera and nothing to the intensity of the human drama that unfolds. All in all, however, the staging made for a compelling ensemble, allowing smooth and well-executed transitions. The decision to place Iago offstage contributed dramatically, underlining his function of manipulating the threads of the story in his favor. His physical presence in the periphery was subtle and sufficient for that purpose, though making him clap to stop the movement of the characters, perform magical passes to “see” through the walls, or extinguish fire with hand movements was something excessive and overdone. Massimo Zanetti was the weakest pillar of this production; he failed to interpret the deeply theatrical sense, the contrasts and changes of emotional climate, the vertigo of a mind plunging into madness, everything that makes Otello one of the most fascinating, complete and refined scores of Italian opera. It was a correct version but with little emotion and, if this work is about anything, it is one of the greatest expressions of emotion translated into music. The leading role found in José Cura an experienced interpreter who has delved into the different facets of the character. That same experience allowed him to overcome the difficulties of the score that are understandably presented to him at this point in his career and vocal maturity in the face of a role that is enormously demanding in both length and power. Although there were a few, he did not allow the grunts and screams to dominate as other interpreters of the role have resorted to to give more realism to the character. Carmen Giannattasio is a soprano with the ideal lyrical timbre and figure for Desdemona. If the love duet failed to create sparks, Giannattasio had her great moment in the final scene with the "Canción del Willow" and the "Ave Maria": here she was able to display her expressive capacity to the maximum, with subtle half voices , ethereal sounds that were lost in melancholy in the air and an undertone of pain and anguish. Carlos Álvarez's Iago was a villain without much subtlety: diabolical, evil and without remorse from the beginning, he remains the same until the end. In the “Credo” —which was transformed into a kind of demonic invocation in front of the fire— Álvarez provided a remarkable vocal and dramatic performance. It was a real treat to listen to Enrique Folger and Guadalupe Barrientos in the brief roles of Cassio and Emilia respectively, accompanied by Carlos Esquivel as Lodovico, Fernando Chalabe as Roderigo, Mario De Salvo as Montano and Fernando Grassi as a Herald. The Coro Estable del Teatro Colón, after an imprecise beginning, gave a beautiful musical moment in “Pietà! Mistero!" and the Children's Choir fulfilled the requirements in the second act. When great expectation is generated in the audience, the risk is that their frustration is directly proportional to that expectation, and that in turn may generates unfair and excessive reproaches. This production, in which the Argentine tenor assumed so many functions, had some successes but lacked the essential: that explosiveness, that incandescence that is achieved perhaps by listening less to yourself and more to the music of Verdi' music and the words of Shakespeare and Boito. These are the keys that make this work one of the most incredible efforts to lay bare human passion. If everything flows, the force of that music and those words hits the viewer like a slap and the experience will hardly be forgotten. Cura's Otello was fine, but despite Iago's magical castings, the spell did not take place.

|

||||

|

|

Hype and Refinement La Nacion Pablo Kohan 20 July 2013 [Excerpt]

To celebrate the bicentenary of Verdi's birth, the Colón scheduled two operas, the first of which, Otello, generated great expectation, both for the significance of this title in the general panorama of the composer's opera production, and for the reappearance of José Cura, now in his double capacity as singer and stage director. Before the start of the opera, José Cura personally announced that the performance would be dedicated to the memory of Ricardo [sic] Oswald. Eight long-spaced bells, one for each decade lived, were struck in tribute as soon as the curtain opened and while the cast stood on stage in suspended animation. Next—and Cura explains the reasons for this decision in detail in the program—a text by Cervantes about his participation in the battle of Lepanto is heard. Cura's need to link Cervantes with Shakespeare, through the personal experience of one and the drama of the other, is as legitimate as it is unconvincing. Moved by the memory of Oswald and with the unnecessary text quickly forgotten, Otello began. And from the first scene of the ensemble, with imbalances between the choir and the orchestra, in which some subtleties and details of high refinement coexisted—the omnipresence of Iago as the troublemaker, always on the fringe and with an ability to stop the dramatic action as if he were a puppet master, a stratagem that gives greater importance to his own thoughts—an overblown pomposity repeats itself and is complemented by performances always on the verge of exaggeration. Cura set his staging on the Colón's rotating disc by dividing the great circle into three sectors, with gigantic radial walls, each one with doors that led to neighboring areas. The passage from one scene to another and from one act to the next take place as the disc rotates and the characters move from one of the three areas to another. The feature, pleasantly surprising in its first appearance, ended up being repeated ad infinitum throughout the entire opera and had the drawback of being slow, inevitably resulting in a certain lack of dramatic pacing. Between moments of visual beauty and the perspective provided by the open doors in the walls, everything unfolded with a certain languor. And in the acting, it was the role of Otello that proved most controversial. Although Iago and Desdemona are portrayed within the limits of what the wickedness of one and the infinite and innocent goodness of the other demand, Cura chose to present the Venetian Moor with a raw cruelty and ferocity, with a violence that exceeds the limits of psychological normality twisted by jealousy. In the third act he has convulsions, moves with pathological rage and brutally attacks Desdemona. Perhaps it was this overwrought construction in all its aspects that caused Cura to neglect his singing. From beginning to end, from the erratic intonation in the love duet of the first act, the harshness with which he used his voice, straining, without a natural delivery, to the moaning cracks in the final monologue, it was apparent. Although Carlos Álvarez fulfilled his task correctly, he did not manage to make an impact with the famous creed of the second act. But it was the ladies in the opera deserve all the accolades. Guadalupe Barrientos showed more than enough theatrical and vocal presence in the few moments she was required. And Carmen Giannattasio got the biggest applause of the night. Restrained, confident and very musical, she closed her work offering "The willow song" with a crystalline, fine and moving voice. The last scene deserves a final paragraph. More than a decade ago, in a Beni Montresor staging, Otello, who also happened to be José Cura, the director was chastised for not letting Otello reach Desdemona's body to give her that longed-for last kiss. On this occasion, a strange tumult, with swords and knives, develops in Desdemona's room and in the confusion Emilia ends up dead while Iago fails to flee and is wounded by Otello. The ensign remains on his knees, as if imploring and begging for mercy. Then, yes, the Venetian Moor lies down next to his wife, not on her bed but on the floor next to it, and, embracing her, kisses her. With Iago, two meters away, crying, as the stranger, the main and only witness.

|

||||

Quincho Talks Ambito Charlas de Quincho 22 July 2013

[Excerpt] The polar cold plagued Buenos Aires but it did not diminish the heat of the great performance at the Colón theater, much less the return of the Rosario tenor José Cura, who came from Madrid with an ambitious plan: to sing Otello by Verdi and also fulfill the role of régisseur and set designer. The misfortunes of the innocent Desdemona and Otello's perfidious suspicions, jealousy, added passions to Cura's story, although his voice did not help him on this night. Cura likes to sing in this theater that once told him they didn’t want him and didn’t appreciate his talent. He already did it in 1999's Otello, albeit with a fresher voice and greater energy. Then he also dazzled the audience with his naked torso and enviable musculature, forged by paying for his studies by giving gymnastics classes. Now he is somewhat overweight and prudently appeared on stage dressed in a wide black robe. Commenting on these issues were [various audience members]. “This is a real Moor from Venice,” said some. Others were silent. Before Otello, by Cura’s decision, there was an emotional moment. The audience was invited to remember Roberto Oswald - the legendary régisseur of unforgettable performances at the Colón who passed away ten days ago - with eight strokes, one for each decade he had lived. The metallic ringing was infinitely painful. But immediately afterwards, also by order of Cura, Otello was linked with Miguel de Cervantes and the Battle of Lepanto. Few understood the reason why and most wondered when the show would begin. Cura's shifting stage immediately captured attention. The revolving stage moved in semicircles moving about the choir, sailors, slaves, soldiers, servants and women of the town--without respite for the duration of the two and a half hours show. The incessant rotations to the right and left undoubtedly demanded laudable efforts, but not all results were equally praiseworthy. Someone said that some singers crossed themselves in the hope they would not get dizzy and maintain their balance on that unstable ground that tended to jolt them about. Afterwards, in the Edelweiss restaurant, praise was heard for Cura's special way of singing, for his "emotional recklessness." And while some connoisseurs claimed that his voice sounded poor, others highlighted the attributes of the tenor. "Certainly, that's how fame is built," concluded one, almost philosophically.

|

||||

|

Act III

Aside from the remarkable over-arching set design that allowed continual flow of thoughts and individuals throughout the opera, Act III introduced some of the most interesting, unique, and insightful elements in the staging of Otello at the Colón.

As the curtain rises on Act III, the flag that Otello had just torn from the wall remains crumpled on the floor, a clue that for Cura the opera is set adrift from time: all that has happened, all that will happen, will be compressed in time to add to the urgency and intensity. Rodrigo arrives to announce that the delegation from Venice will soon arrive; Iago leaves to find Cassio whom, Iago assures Otello, will offer proof of Desdemona’s deceit; and Desdemona arrives to plead with her husband once more on behalf of Cassio. At the mention of Cassio’s name, Otello’s initial calmness is replaced with agitation and he asks Desdemona to wrap her handkerchief around his throbbing head; she attempts to comply with a colored (purple from our seats) cloth.

Otello: Woe if you have lost it. A powerful witch enchanted its fibers. In them is held a great magic, dark and deadly. Careful. If you lost it -- or gave it away, misfortune will befall you. Desdemona: Is this true? Otello: I speak the truth!

Kira Cliff Notes: The handkerchief, of course, is only a symbol but a powerful one—and while neither the play nor the opera is simply about the handkerchief, they are both about what the handkerchief represents: honor, fidelity, integrity. Iago selects the one item that physically represents all the traits he lacks and is able to distort reality for Otello based on possession of the traits that mean most to the general.

But the hanky also gives us additional insight into the nature of Otello. In the Shakespearean play, the Moor explains more thoroughly about the fabric: the handkerchief was given to Othello’s mother by a two-hundred year old prophetess who told her that as long as she kept the piece, she would keep the love of her husband. But “if she lost it / Or made gift of it, my father's eye / Should hold her loathed" (3.4.60-62). Othello’s mother gave the handkerchief to her son as she was dying so he would also have the gift of enduring love.

But there is more to the handkerchief than the blessing (or curse). As Othello tells Desdemona, its silks came from silk worms and the markings were dyed in fluid drawn from embalmed virgin hearts. The pattern of strawberries on a white background strongly suggests the bloodstains left on the sheets on a virgin’s wedding night, so in construction and expression the handkerchief implicitly suggests a guarantee of virginity as well as fidelity. That someone else has possession of the talisman, to the superstitious mind, would mean someone else also possesses Desdemona.

Finally, as Otello reveals the origins and mystical abilities of the handkerchief, he also reveals more about himself and his formation: though his belief system is based on Christianity and there are Christian elements scattered throughout both play and opera, Otello’s embrace of mysticism and magic emphasizes his ‘otherness.’ Otello isn’t separated from the Venetians by skin color alone; he is separated by experience, upbringing, and belief in the mystical.

Director Cura also added his own element of mysticism. At the same time Desdemona is unable to provide proof of her honesty and integrity, she continues to champion Cassio. Her husband shows increasing erratic behavior, including the threat of physical violence—but Cura has allowed Iago to return to the periphery of the stage, not part of the scene but not outside of it, and appears to give him the gift of control over Otello: the puppet- master has returned.

Cura is at his finest as a performer when he channels absolute pain and despair; not only does his voice convey the agony and hopelessness of the moment, but his body resonates in pain, his face reflects the sorrow, and his overall stillness projects a man in the fragile state of disintegration: we come to one of the high points in the opera: Dio! Mi potevi scagliar tutti i mali / God, you could have thrown every evil at me. Beautifully staged, beautifully rendered, beautifully acted, Cura ensures this moment became the emotional pivot point in the opera.

Cura makes the explosion from reverie to reality both vocally and visually memorable: he snuffs the flame from the candle as he rouses himself to action. Iago returns to prepare Otello for Cassio’s imminent arrival; the Moor hides behind one of the great doors at the entrance to the fortress and listens as Iago manipulates reality to further his plans. Eventually, Cassio produces Desdemona’s handkerchief—the physical evidence Otello needs to prove Desdemona has transferred her affections to Cassio. Events move quickly: the bugles blow to announce the arrival of the Venetians, Iago tells Cassio to leave quickly and as Iago helps him into his ceremonial garb, Otello asks how he should execute his wife, whom he, as the governor, has found guilty of a crime while Iago offers to execute Cassio. Otello promotes Iago to Captain.

Kira’s Cliff Note: Lodovico is Desdemona’s cousin.

Director Cura’s vision is pronounced throughout the rest of the act. When Otello calls Desdemona a demon and attempts to attack her, the Venetian males intercede, forming a protective barricade: never is Otello’s status as outsider more evident than when the society he has worked so hard to integrate unites against him. When Otello is replaced as governor by Cassio, he doffs his governor’s robe—but Iago picks it up and insists Otello put it on; it is essential to Iago that Otello views himself as remaining in command and control. As Desdemona and the others lament, Otello spies a small grouping of slaves that have come ashore with the ambassadors. Past becomes present as he stumbles to them, lifts their burdens from them, embraces them, finally clothes one in his governor’s robe and walks them to their freedom—spectacularly insightful dramatically and painful emotionally. When he returns via the dock, he is in the obvious throws of an epileptic fit, physically and vocally out of control: just moments before Desdemona was the demon, now the demon lives inside Otello and there is no escape. He orders all away before he collapses on the dock, the scene of his great victory in the opening scene. And still there is more from Director Cura’s vision: instead of the act ending with Otello prone, he has his Moor slowly pick himself up and stagger into the fort to sit at the far end of the table opposite Desdemona, who is waiting for him. They sit in silence until she slowly, sorrowfully walks towards their bedroom, pausing only to collect the prized handkerchief that Otello holds out for her as she passes. A magical moment.

Kira’s Cliff Notes: What to do about Shakespearean time? It expands, it contracts, it folds in on itself and it proceeds double-fast. For this staging, Director Cura seems to approach time as an abstract: Otello marries Desdemona and kills her twenty-four hours later. ‘Things’ happen outside his timeline that have direct bearing on the plot development but those things merely inform his staging. Thus, Otello lands in Cyprus as the military governor and the next day he is called back to Venice. Otello marries a virgin who becomes a courtesan as soon as she leaves the marriage bed. Iago steals Desdemona’s handkerchief, never leaves Otello’s side yet still manages to tuck into Cassio’s bunk so he finds it when he wakes.

As with all things Shakespeare, there is a theory for this seemingly random abuse of time: the necessity to add urgency and propulsion to the drama. According to the Wilson-Halpin theory of Double-Time, “Shakespeare counts off days and hours, as it were, by two clocks, on one of which the True Historic Time is recorded, and on the other, the Dramatic Time, or a false show of time, whereby days, weeks, and months may be to the utmost contracted.” According to A. F. Sproule writing for the Shakespeare Quarterly, “One set of time references produces the True Historic Time, or the duration of the main action. The time required is said to be about thirty six hours. The other set of time references, the references which cannot be reconciled to the main action, produces the Dramatic Time. The time suggested for the latter is rather indefinite, but a period of two months may strike the average.”

So there it is: Outside the world of Cyprus two months pass; in Cyprus, those events inform the plot but the actual time covered is only a couple of days. The disconnect between Historic and Dramatic time leads to infuriating logic conflicts and issues and how well the director handles the difference goes far in determining how well the evening is balanced.