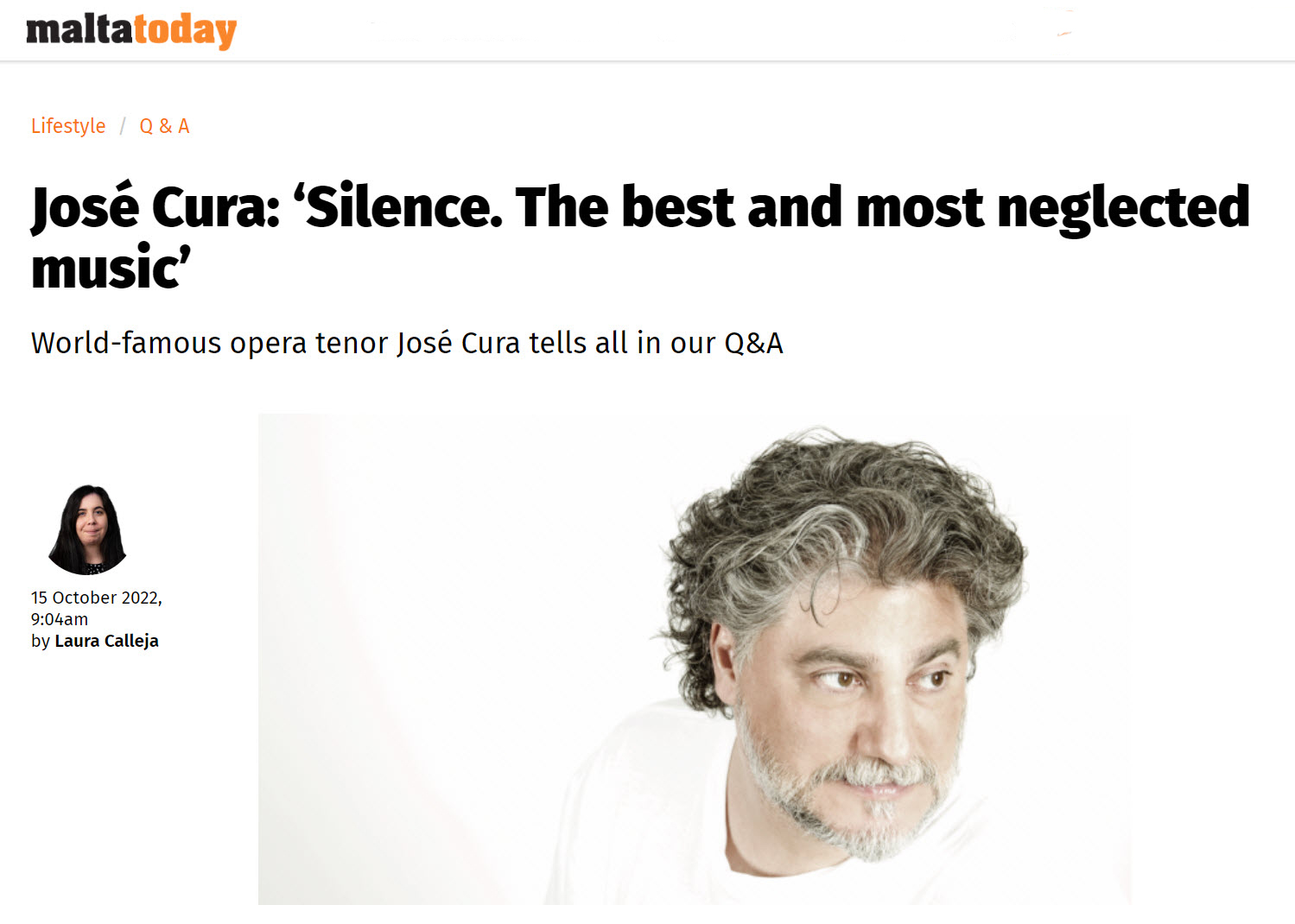

Mama Mia! That's some

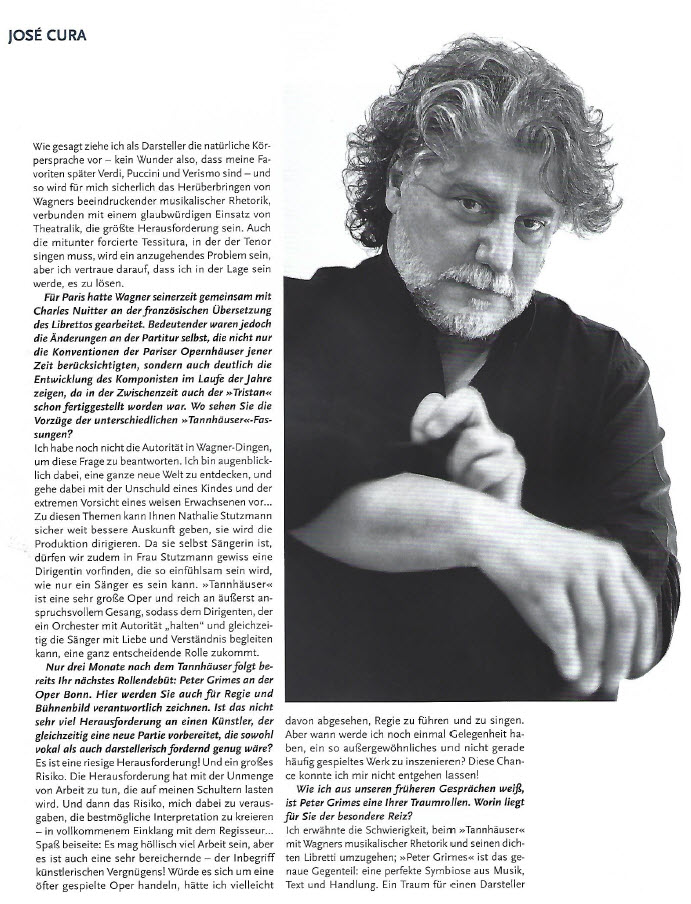

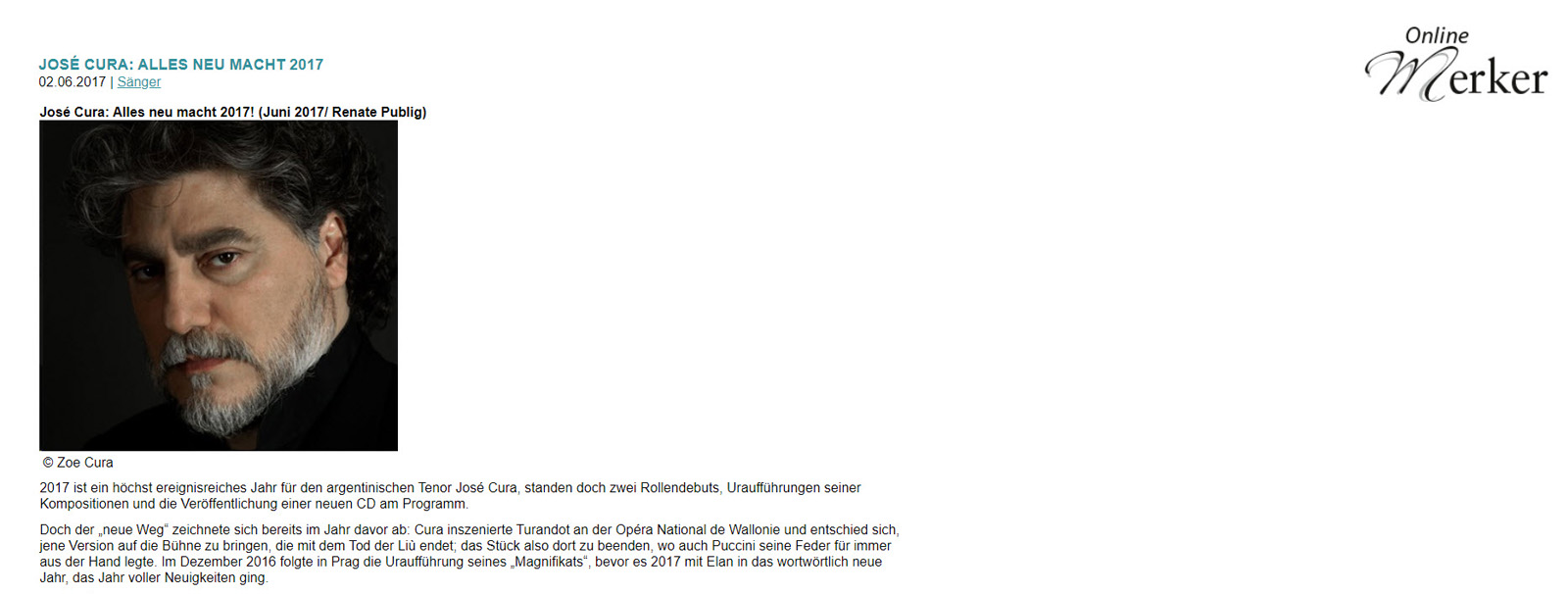

tenor

Shanghai Daily

Created: 2007-2-9

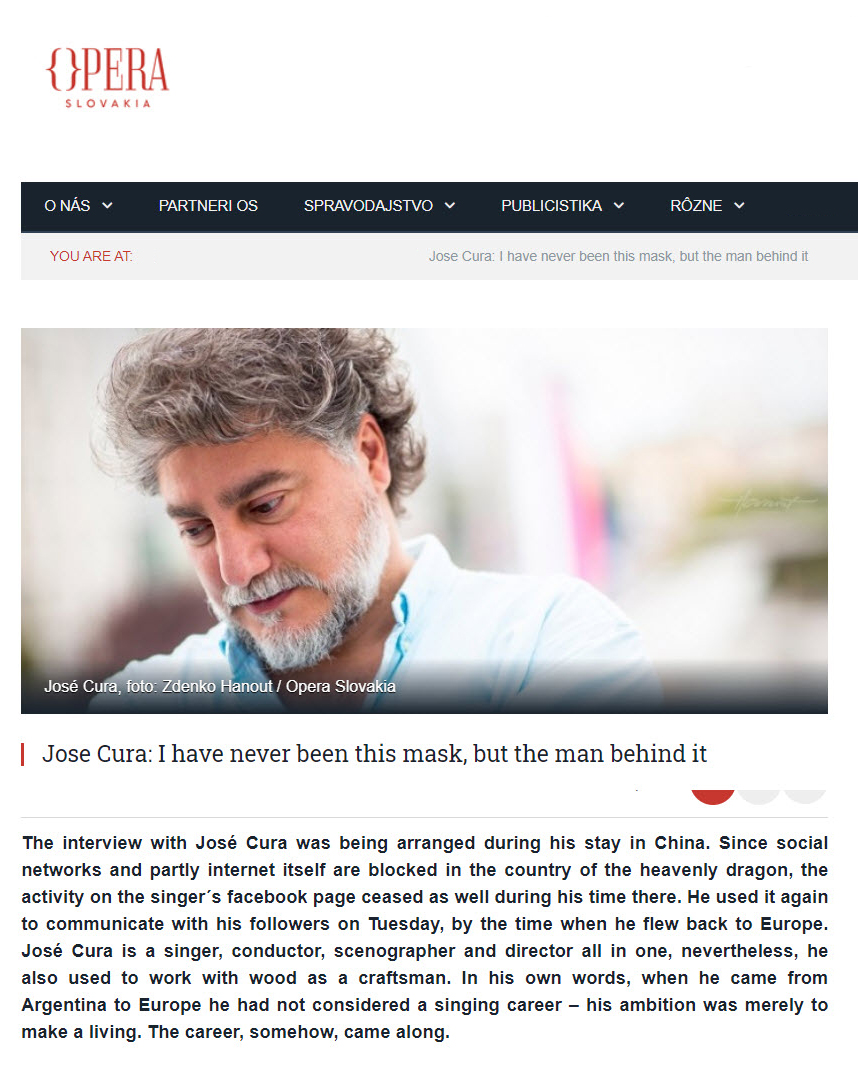

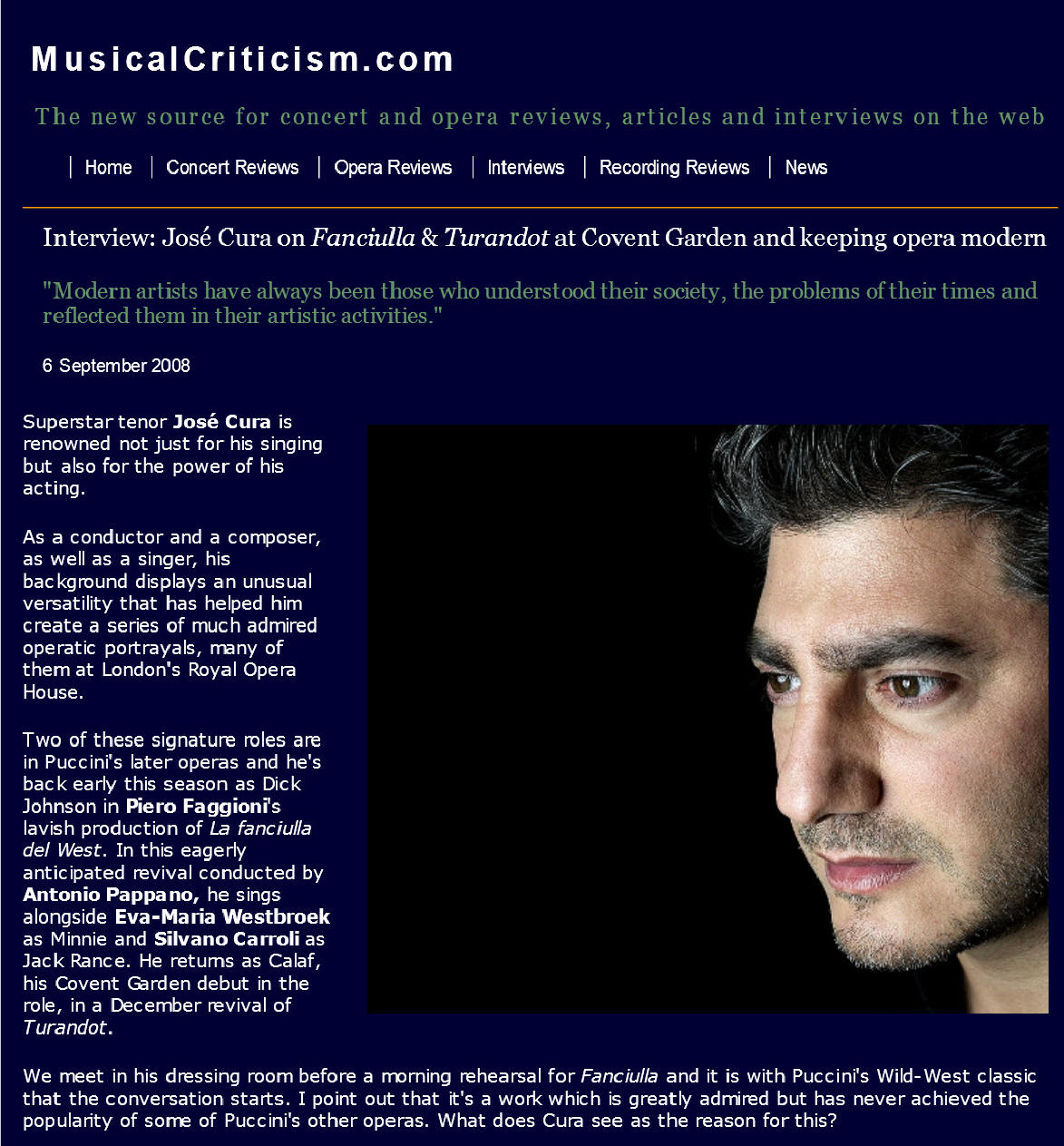

Argentine tenor Jose Cura sings

a superb Prince Calaf in "Turandot" and immodestly says his

"good shape, big and strong" is ideal for the role. But he calls

the greedy, kingdom-hunting character "disgusting" and hopes

Chinese audiences won't think ill of him, writes Michelle Qiao.

Opera singers often identify with, even love their roles, but

Argentine tenor Jose Cura loathes "Prince Calaf," his character

in the opera "Turandot" staging this weekend at the Shanghai

Grand Theater.

"'Turandot' is not a love tale, but a tale of interests and

greedy people trying to seize power," the tenor said during

a press conference this week.

"The character of Calaf is not romantic. Chinese Princess Turandot

loves Calaf but Calaf wants her for her kingdom, money and power.

He is superficially charming but behind the mask he's an idiot,

disgusting.

"The Prince has lost his own kingdom and searched in the world

for another kingdom," says Cura. "He put in danger the people

he loves to obtain something he wants."

"I'm sorry that for the first time in China, I must play an

idiot. Please don't think ill of me or link me with the character."

However, playing the black-hearted and designing prince, the

tenor still impressed his Shanghai audience with his charming

"surface" and superb voice last night.

This production of "Turandot" is a treat for the eyes because

both Cura and soprano Paoletta Marrocu, who sings Turandot,

are in good shape compared with other overweight Calafs and

Turandots in the opera world.

"My good shape, big and strong, is the result of many years

of physical training in my early days," says Cura, wearing a

pink sweater and a pair of comfortable white sneakers. "In the

past, a long time ago, I weighed 20 kilos less. Now I'm 44,

20 kilos more, and 20 years older."

But he can still pass for a prince.

"For roles in modern theater, if you look like the character

it's better for the theater fantasy. Old audiences gave the

greatest importance to good singing. But the younger generation

likes good spectacles."

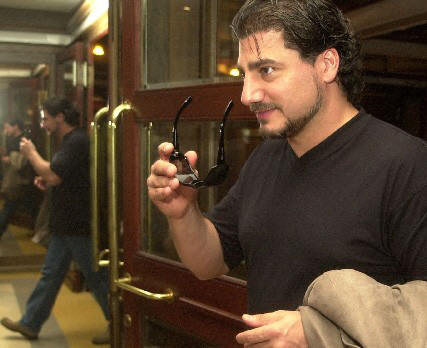

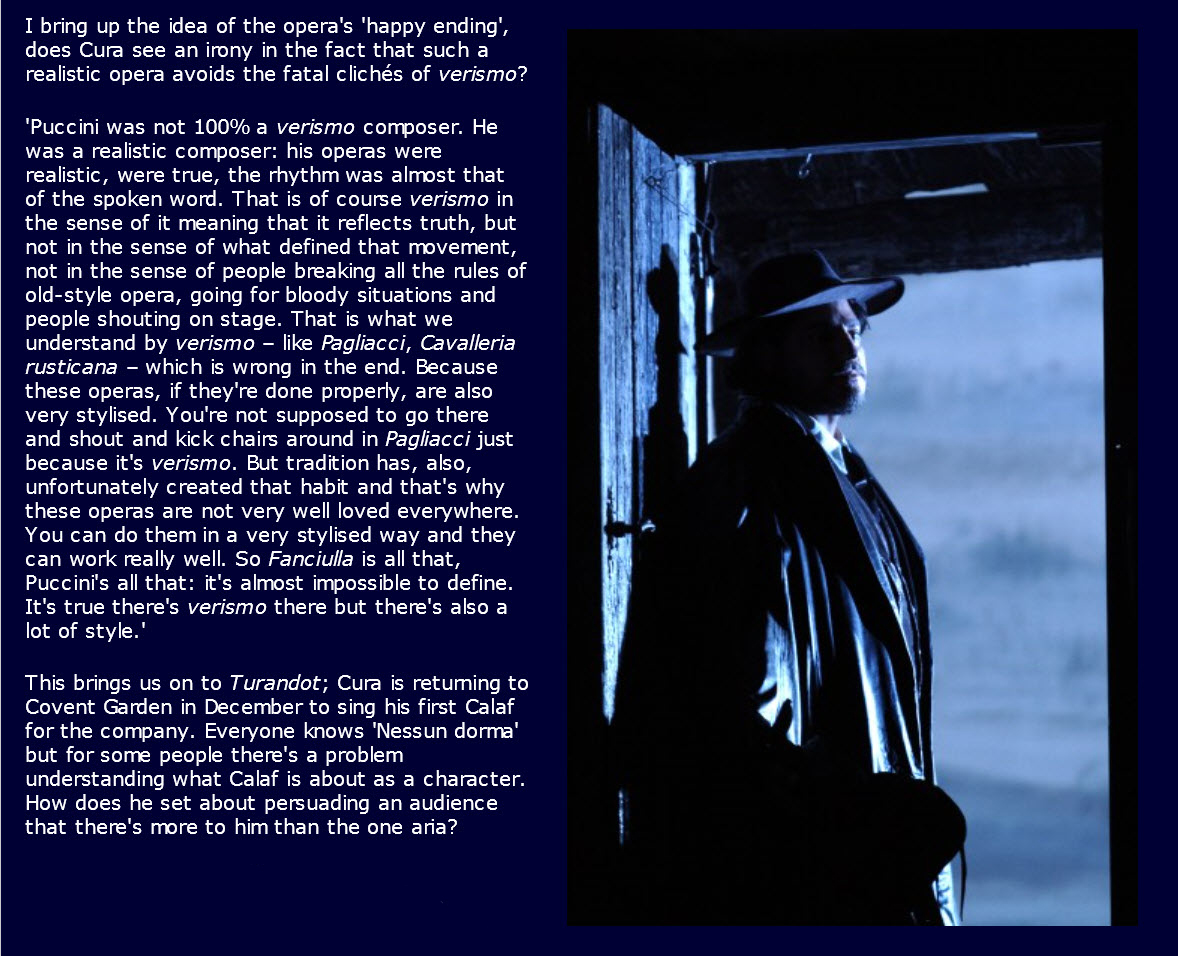

Cura's charisma shone from the start of the production created

by the Shanghai Grand Theater and the Zurich Opera House, when

he showed up like a sexy secret agent in a black leather jacket,

a tight-fitting gray vest and shades.

In sharp contrast to the antique green copper hues of the set

and the icy demeanor of Princess Turandot, Prince Calaf casually

smoked a cigarette and searched his laptop for answers to Turandot'

love-or-death riddles.

He even stretched on the ground to sing his famous aria "Nessun

Dorma," perfectly striking high B. His melodious vocals with

beautifully held top notes were expertly controlled.

With the Bund as the backdrop, the prince ended his dangerous

love pursuit with a romantic candle-lit dinner with the cruel

princess who had actually fallen in love and changed her weighty

formal robes for a fitted scarlet evening gown.

"Cura was not only acting, but also creating," says Zhang Guoyong,

head of the Shanghai Opera House. "He demonstrated the talent

of a true master."

Unlike other opera stars who often give pleasant, bland comments

during interviews, Cura was bold and forthright. "Mama Mia,"

he occasionally exclaimed when occasionally targeted with surprising

questions.

"I didn't know I'm famous in China," he said. "I thought I was

completely unknown and so I could relax on stage. Now you will

expect so much from me and I must rise to the challenge."

No matter whether he likes it or not, Cura is widely known in

China as "the world's fourth tenor" (after Luciano Pavarotti,

Placido Domingo and Jose Carreras).

"You can say I'm the successor of the three tenors who are as

old as my father and you are also the successor of your own

parents, right?" he says. "We are the next generation and the

world was so different from their time around 30 years ago when

CDs and DVDs had just been invented. "Now we face a big crisis

of new media and the Internet and MP3s will be the future. If

Bach were alive today, he might use a computer to write music.

It's very complicated, not simply being a successor. It's difficult

to succeed in the opera world today."

Cura has been a rare artist who's not only a tenor, but also

a conductor and composer. In addition to the two "Turandot"

operas, he will conduct the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra for

a concert at the Shanghai Grand Theater on February 14.

"I will also try the role as an opera director," says Cura.

"In every role I have put all my love, so I cannot say which

role I'm best at. But what makes me happiest is conducting.

I meant to do some deep, profound music for the Shanghai audience.

But the organizers asked me to do some romantic music for Valentine's

Day, such as 'Romeo and Juliet'."

As a tenor of IT times, Cura has an iPod with him that is filled

with jazz, symphonic music, and his favorite singer Karen Carpenter

- but no operas.

"I don't like some untuned pop music," says the tenor. "I cannot

have music as a background. If music is there, I will have to

pay attention to it. So I only like music with dramatic objectives."

Despite its modern elements, this production of "Turandot" closely

follows the original Puccini plot. Princess of China, the dangerously

beautiful Turandot, refuses to marry anyone but the man who

can answer her three riddles. All suitors who fail will be put

to death.

Enchanted by her beauty - and kingdom - the unknown Prince Calaf

dares to try and at last succeeds, at the cost of the life of

his slave girl Liu, who is in love with him.

"Prince Calaf has a disgusting personality," repeats Cura. "He

can be a citizen of any country of any race, like the greedy

people of all times. They don't hesitate to kill their mother

to succeed."

Well, maybe Cura feels it's a pity to show up as a man with

disgusting personality for his China debut. But through his

on-stage acting and off-stage talking, the tenor has showed

Shanghai the unique personality behind "the fourth tenor."

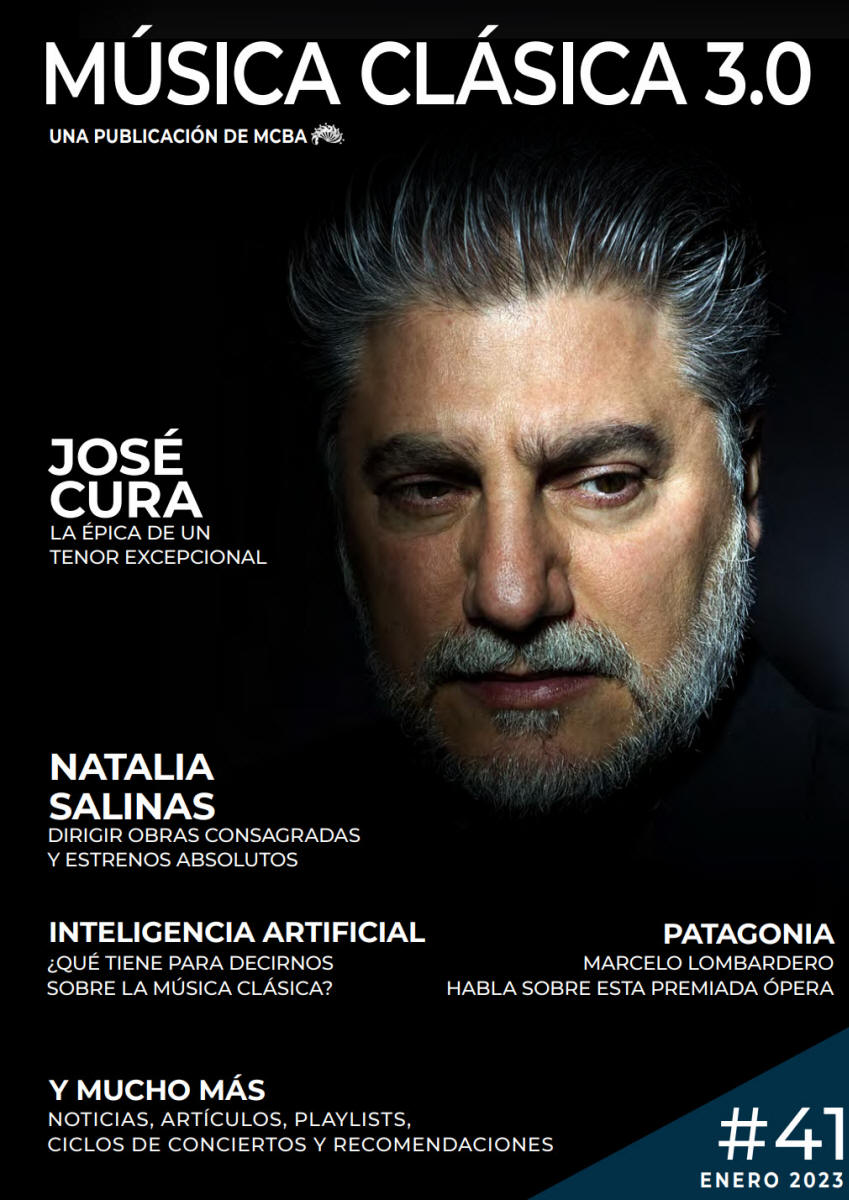

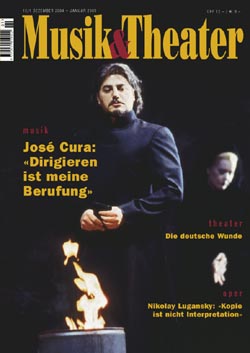

The Two Loves of José Cura

Publico.pt

19 October 2007

Pedro Boléo

The voice of

Argentine José Cura can be heard today in Lisbon. And that

is only one part; after the interval he picks up the baton and takes

Beethoven by the horns. Rebelliousness or professionalism?

He has two loves: the baton and the voice.

Two forms of expression of the same personality. José Cura

says that he used to want to be a maestro, but had to sing to sustain

his family. Now it is not quite so true: the Maestro

José also sustains the family, and Cura did not stop being a tenor.

Today, in the Teatro San Carlos in Lisbon, he will sing some arias

from opera but the main course of the evening is the 9th

Symphony of Beethoven, conducted by this artist in search of joy.

The same work, the 9th, the most emblematic of the ‘genius,’

as the maestro without fear states.

How? Does he sing and direct the singers?

Is he behind and in front of the orchestra? José Cura explains:

“The artist prepares a show—it can be one part, the other part,

or both.” In 2003, in Hamburg, he directed an opera and after the

interval he jumped on stage to sing another. Of course:

“Nobody finds it strange that DeNira goes behind the camera.

Or that Woody Allen is the actor in his films. But in opera…”

José Cura fights against the established ideas

and prefers to consider himself a total artist. Or at least

an artist free to do as he wants. A rebel? “Not in an

unpleasant sense, but an artist has the right to create following

his own reality and instinct,” he says.

He has already

been told he does too many things: he responds that to be

an artist “is not only to be safe and avoid risk.” He has

already been criticized for singing and gesticulating, as if directing

the orchestra: he argues that an artist “must be true to their

own nature.” Before we even ask about the 9th Symphony

he is about to conduct, José Cura adjusts the chair in his dressing

room at the San Carlos and adds Beethoven to the discussion.

“If they had dictated to Beethoven what he should have done, he

would not have been able to do what he did to the art of the symphony.”

And remember: “About the symphony they said it was as unpleasant

as the sound of a bag of nails. That it was banal. That

there was 55 minutes more than what was needed. Today, we

know that it is the cornerstone of symphonic music.”

And will Cura launch

himself into the ‘cornerstone’ as if it were nothing? He has

the size, the physical strength, and the enthusiasm, certainly,

but does he have the right stuff? “Yes, I feel the responsibility,”

says the singing, slouching in his chair. “But on the other

hand, it is simple: simply respect what the genius wrote.

We must put ourselves into the hands of the composer.” It is then

that José Cura leans forward and starts offering a thousand ideas

about how the symphony could go. He puts himself in the hands

of Beethoven. “Many conductors today still think they can change

a symphony to the better. It is a fairly common arrogance.

Even if it was ‘to improve it’…. Does it need to be improved?” Asks

José Cura. We are, by the way, reminded of the version of

the 9th by Maestro Herbert von Karajan, and he said jokingly:

“It was you who said it, not me.” But he is now out of jokes:

“There were excesses of a pseudo-romantic kitsch for a while.

Maybe people needed it that in the post-war period- a mist, one

to hide the exaggerated, excessive mannerism, distilled, but it

has its time. We must put this in its historical context.”

Today things are different, he says. “Also because there are

better editions of the scores. And we arrive at impressive

conclusions. For example, Beethoven wanted certain passages

taken more quickly.” And just so there is no misunderstanding, the

Argentine maestro warns: “Many people will find my interpretation

strange and original. But it is only what is written.”

We then move to

José Cura, tenor—the same man but a star with different demands:

attitude on stage, physical appearance, theatrical capabilities.

Is this just a marketing of his image? “I do not know what

is marketing,” he says immediately. “It has to do with being

beautiful or not.” And he confesses that “many roles that I would

like to play are or stranger or ugly types, but they do not let

me do them. It is true that in spite of everything, we all

have a physical self that determines the type of character.”

José Cura is a

man of 45 years, an opera superstar but also a simple and direct

person, with a moving honesty in how he speaks. He is not

a man of poses, although he knows how to be an actor and give a

performance. The keyword that connects to success is “professionalism

– a word that is used often but is worth ever less.” But in music

it is a different case: “It is a problem that music is not

like medicine. If a surgeon doesn’t have the degree, then

he is not going to cut into your intestines. But in music

the title does not mean anything. Many people say that are

[professional] but they are not. They deceive the public.”

We could see in

him as a modern and multifaceted Pavarotti, one who goes to the

gym, takes photographs (another great passion) plays guitar, singes,

conducts, directs. But no—he is only José Cura, a rebel and

a respectful, popular artist in opera houses, a stage animal, a

man with an open mind and with ‘social commitments’ (Cura is a founding

partner of the Portuguese Association against the Leukemia).

Is this rebellion?

Yes and no. He recalls Beethoven, once again: “If it were

not for the rebels we would be in the stone age.”

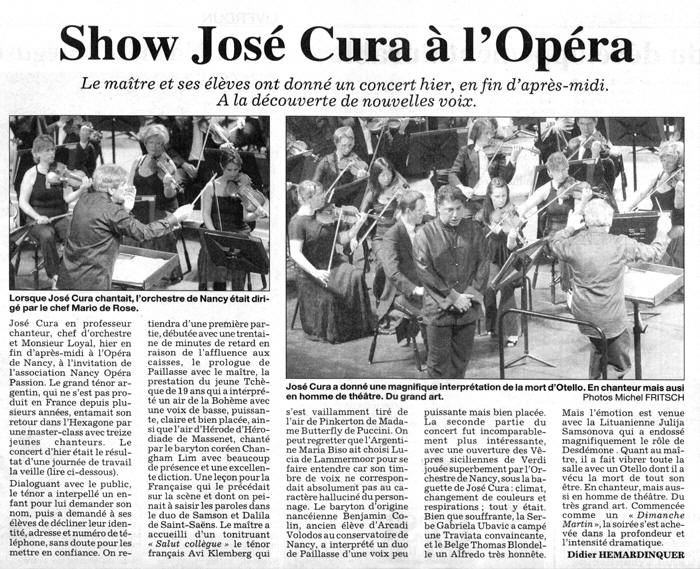

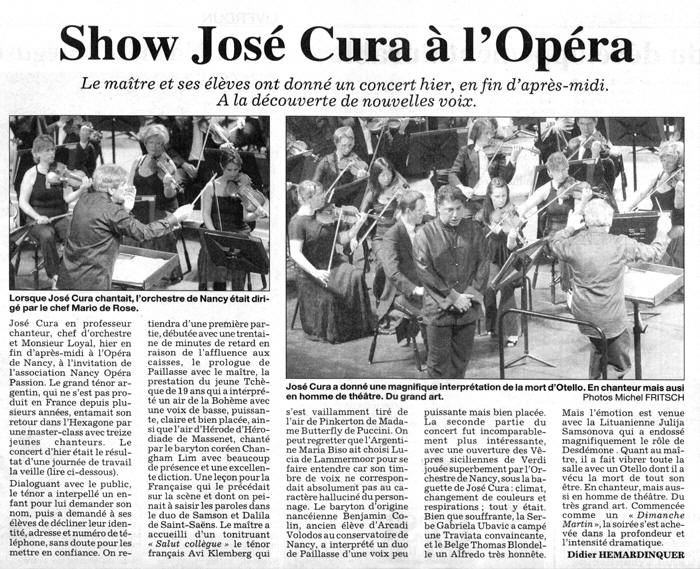

The Gala Concert

Lisbon, Teatro

Nacional de São Carlos

Today at 21h Chelsey Schill (soprano), Maria Luisa de Freitas (soprano),

José Cura and José Manuel Araújo (tenor); Johannes von Duisburg

(bass). Musical Direction [Symphony No. 9]: Jose Cura; Musical direction:

Mario de Rose. Portuguese Symphony Orchestra. Choir of San Carlos.

Arias, Leoncavallo, Puccini, Giordano and Verdi. 9. St symphony

(Symphony Coral, op.125) from Beethoven

Andrea Chénier, a poet

at the Liceu

Opera Actual

Susana Gavina

[Excerpts /

gist]

The

Liceu of Barcelona opens its opera season on September 25 with Umberto

Giordano’s Andrea Chénier, a title that returns to this stage

after an absence of two decades, with fourteen performances and

three different casts, the first headed by Deborah Voigt, José Cura

and Carlos Álvarez. The Argentine tenor … explains the points

of view he brings to this masterpiece of versimo. The

Liceu of Barcelona opens its opera season on September 25 with Umberto

Giordano’s Andrea Chénier, a title that returns to this stage

after an absence of two decades, with fourteen performances and

three different casts, the first headed by Deborah Voigt, José Cura

and Carlos Álvarez. The Argentine tenor … explains the points

of view he brings to this masterpiece of versimo.

Andrea Chénier

is a title that has been on the programmed often at the Liceu;

nevertheless, for more than two decades, “from the 1985-86 season,”

confirms Joan Matabosch, artistic director of the Gran Teatro,

it has not been staged. “It is a work in the repertoire and one

of the most popular in the recent history of the Liceu. Because

of that, programming it has become a small event.” One of the reasons

for its absence in the last few years, according to Matabosch, “is

the need to have great singers.” He has managed to bring together

a cast headed by José Cura, Deborah Voigt and Carlos Álvarez, alternating

with the voices of married couple Daniela Dessí and Fabio Armiliato

together with Anthony Michaels-Moore and another set with Carlo

Ventre, Anna Shafajinskaia and Silvio Zanon. In the pit will

be musical director Pinchas Steinberg. In staging the opera, the

Liceu is not treating itself to a new production this time, something

great theaters are usually expected to do at the beginning of the

season. Instead, they have hired a production from Tokyo designed

by Philippe Arlaud, who this year presented Tannhäuser in

Bayreuth. "It is not a question of this being a radical reading

of Andrea Chénier,” the art director of the Liceu assures,

“but it is not a traditional staging either.”

Jose Cura's presence in the Barcelona opera theater is turning

into something of a habit and is the only one in this Spanish opera

seasons. The Argentine tenor returns with a role he knows well,

that of a revolutionary poet executed by his own comrades in arms.

“I made my début in the role in 1997 in London, and I do not do

it as much as I would like to,” he says with regret during a telephone

interview from Buenos Aires, where he has returned after an absence

of almost nine years. “Since then, I have sung it in maybe four

or five productions. It is not an opera that has become common,

probably because the roles of the tenor and the soprano are very

difficult. Last year I did it in Bologna and it was recorded

on DVD,” he adds. Cura confessed to ÓPERA ACTUAL that he did not

know anything of the Japanese production and joked: “I hope not

to be alarmed. Do you know anything?” he asks.

For the tenor, a test

As far as the vocal characteristic of his role, the tenor underlines

again that it a matter of “a very hard role for a tenor, but also

very interesting because it is very complex. In the first

act, especially in the ‘Improvviso,’ the tenor is very present,

the aria is quite dramatic and written central enough that one must

try to be heard because the orchestra plays loudly. Later,

in the second act—and that is the most tremendous because there

is a great monologue and a great duet—that is where the tenor is

tested and discovers if the role fits your voice or not. The

third is simpler and the fourth is complicated because the first

aria is practically written for a lyric tenor, very dreamy, almost

with the scent of the aria ‘E lucevan le stelle’ from Tosca,”

according to Cura. “It is a bit of the farewell. And later

is the final duet, which is very badly written—and I don’t say this

only because it is super-orchestrated but it has that effect, though

it is tremendous. It is there where it really returns to test the

tenor to see if one is a tenor for Chénier or not. This is

an opera which time and time again puts the singer to the test.”

Singers such as Mario del Monaco, José Carreras, and Plácido Domingo

have interpreted this role. “Franco Corelli became famous

because of it. It is a role in which, much like Saint-Saëns’

Samson or Verdi’s Otello, even though it is a minor work when compared

with these titles, the tenor is greatly illuminated and it can even

mark your career.”

Giordano’s opera, with libretto by Luigi Illica, is inspired

in part by a real person, a French poet with the same name who was

a partisan in the French Revolution, although the execution of Luis

XVI caused him to redefine his support, finally being executed after

accusations of being a counterrevolutionary. “I have a book

at home about the life of the real Chénier, although as usual in

opera the history is exaggerated for the melodramatic requirements

of the plot. He was a revolutionary who died for speaking the truth.

He was an honest person and when he saw the ideals that he had originally

defend transformed into what he had been criticizing, he decided

to separate himself. The opera denounces the system in power,

independently of the party who holds it. In this sense, the

opera Andrea Chénier is both very durable and very current.” The

tenor emphasizes a phrase in the second act, “that is almost not

heard but which summarizes the opera: ‘The old courtesan inclines

her head to the new God.’ In the end they all pay homage to

the same thing, independent of its color. This phrase is turned

ultimately against Andrea Chénier,” the tenor says.

Other horizons

José Cura confirms that he does not have any other projects planned

in Spanish theaters, in particular the Teatro Real. “In February

2006, when I was performing at the Liceu, the directors of the Real

approached me and said they wanted me to return. That seemed

good to me and so I told them to go ahead, and that was it.

Perhaps there is no repertoire for me at the Real,” he said.

Nevertheless, he has agreements with the Barcelona theater through

2011, although he can not tell us what since “one of the agreements

I have with the theater is not to reveal anything until they announce

the season. The Liceu,” he continued, “is a very well organized

theater. Not even the Metropolitan in New York is signing

that date. In this, the Liceu is an international example.”

In respect to his participation in the macro project of José Moreno

to build the Theater of the Three Cultures, a project from which

soprano Montserrat Cabellé has removed herself, Cura affirms that

he does not know anything, although he has not disassociated himself.

He is waiting for that call from Moreno. “The last time we spoke

he told me all was moving ahead and that he would talk with us when

the project was more firm.” And he insists that “I have never withdrawn

but rather suspended [my involvement]. If when they finish

my calendar allows me, I would love to continue with it.”

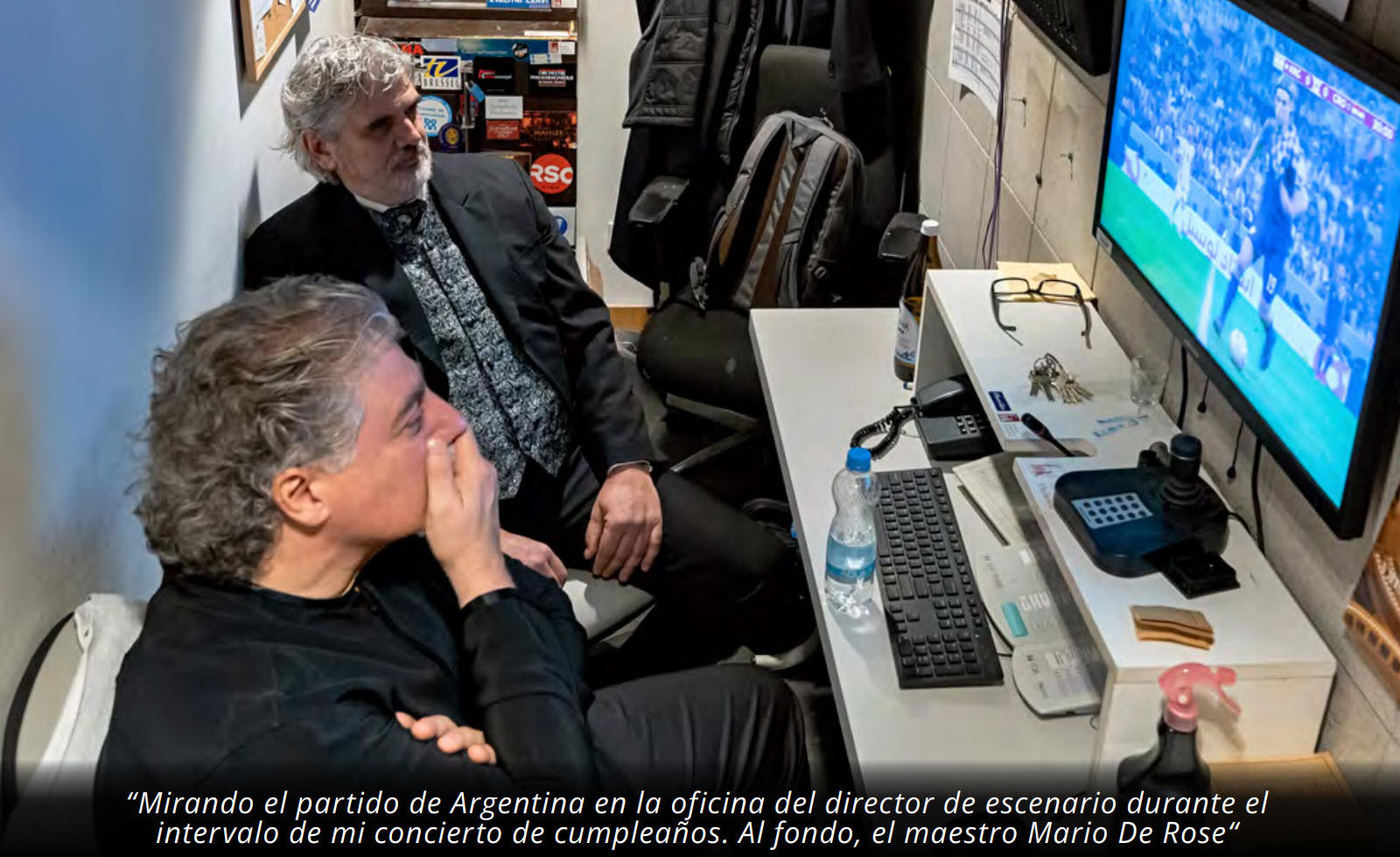

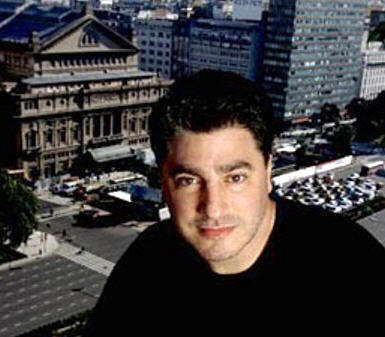

José Cura Returns to the Colón

His voice

will be heard again

After eight

years without a role in a production at the theater, the tenor

will star in the main role in Samson et Dalila, which premiers

tomorrow. Tuesday he sang in Rosario, his city, at the

festival for the 50th anniversary to the Monument

to the Flag.

La

Razon

Geraldine Mitelman

[excerpts]

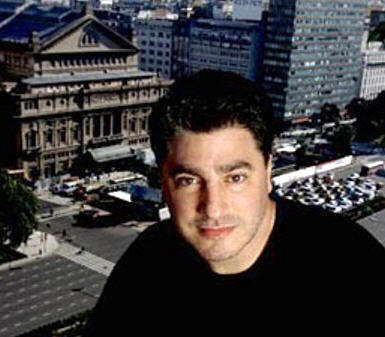

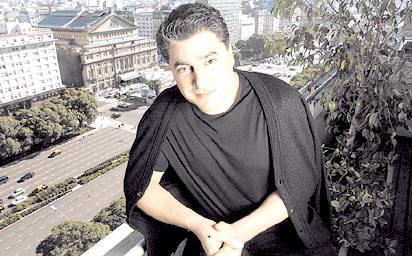

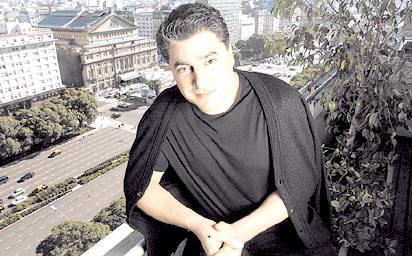

Dressed

in a black T-shirt and looking very casual, the Rosarino tenor José

Cura gave advanced details of Samson et Dalila, the opera

by Camille Saint-Saëns that he stars in, along with mezzo soprano

Cecilia Díaz. Dressed

in a black T-shirt and looking very casual, the Rosarino tenor José

Cura gave advanced details of Samson et Dalila, the opera

by Camille Saint-Saëns that he stars in, along with mezzo soprano

Cecilia Díaz.

The singer, who has not performed in the Colón

season for eight years, proved to be happy and very funny during

the press conference held at a central hotel. After recalling

“the old days when nobody knew him here” until now when he returns

successful (he is recognized everywhere and at present resides in

Europe, where he lives with his wife and children), Cura discussed

the make-up of the character he has interpreted so many times.

“There are two ways to read Samson, and one

of them is wrong. He can be interpreted as a Christ figure,

like a hippy of the 60s. No. He belongs to the book

of Judges, revolutionary leaders and not good boys. Samson

incites the town to raise weapons, which transforms him into a sort

of “Che Guevara” of the age,” he explained. Before that disconcerting

parallelism, Cura had been referred to as the heir apparent to the

artistic direction of the Teatro Colón. “I would not accept

a future offer for the position, but if they offered me the job

of principle guest director, I would say yes,” he affirmed amidst

laughter directed at the current artistic director,

Marcelo Lombardero, who was in the room.

Besides discussing his approach to the work

Samson et Dalila, Cura focused on his role as compose in

advance of the 8 July premier in Rosario of his work Sonetos.

Later, in response to the question of his possible return to his

country, he said: “You never know, life has many returns.”

José Cura

ParaTi

19 July 2007

Julieta Mortati

The renown Argentine tenor, currently living

in Madrid, is in Buenos Aires for the opera Samson et Dalila in

the Teatro Coliseo. In a chat with Para Ti, he related how

he studied music, martial arts, and even gave classes in body building

to survive. He began to sing at the age of 27 because “I

discovered that my voice could pay my bills.” He is considered

to have one of the best voices in the world for its interpretative

quality.

.jpg) José

Cura (44) traveled to Argentina to attend the golden anniversary

of his parents (the celebration is on Saturday 7 July in Rosario,

his hometown). He is accompanied by his wife, Silvia, and

their three children: José (19), Yazmín (14) and Nicolás (11).

The visit, at first a secret, was quickly divulged and the family

plan was subsequently interrupted by five performances of Samson

et Dalila (by Camille Saint-Saëns) in the Teatro Coliseo, with the

artistic support of the Teatro Colón, and in Rosario with the festival

of the 50 years of the Monument to the Flag and a chamber concert

in commemoration of the 25th anniversary of Mozarteum,

(8 July) where he will present the world premier of the

Sonetos cycle, seven pieces

composed for the poetry of Pablo Neruda. In his last week in this

country, he walks with bags under his eyes and runny nose.

“On the stage it is cold,” says Cura of the Teatro Coliseo,

“And it was not only cold but windy! Yesterday it was blowing

off my shirt and the boys in the chorus were wearing cravats and

scarves on stage. We endured, “but in the end the body just

says ‘enough!’. José

Cura (44) traveled to Argentina to attend the golden anniversary

of his parents (the celebration is on Saturday 7 July in Rosario,

his hometown). He is accompanied by his wife, Silvia, and

their three children: José (19), Yazmín (14) and Nicolás (11).

The visit, at first a secret, was quickly divulged and the family

plan was subsequently interrupted by five performances of Samson

et Dalila (by Camille Saint-Saëns) in the Teatro Coliseo, with the

artistic support of the Teatro Colón, and in Rosario with the festival

of the 50 years of the Monument to the Flag and a chamber concert

in commemoration of the 25th anniversary of Mozarteum,

(8 July) where he will present the world premier of the

Sonetos cycle, seven pieces

composed for the poetry of Pablo Neruda. In his last week in this

country, he walks with bags under his eyes and runny nose.

“On the stage it is cold,” says Cura of the Teatro Coliseo,

“And it was not only cold but windy! Yesterday it was blowing

off my shirt and the boys in the chorus were wearing cravats and

scarves on stage. We endured, “but in the end the body just

says ‘enough!’.

What does it mean for you to sing in Buenos

Aires?

Well, it is not the same thing to sing for

your people and your family as it is to sing for those who have

your respect because they are your fans but who do not know you,

do not know the man on the other side. When you sing in your

country, you know that in the audience are people who knew you as

a boy.

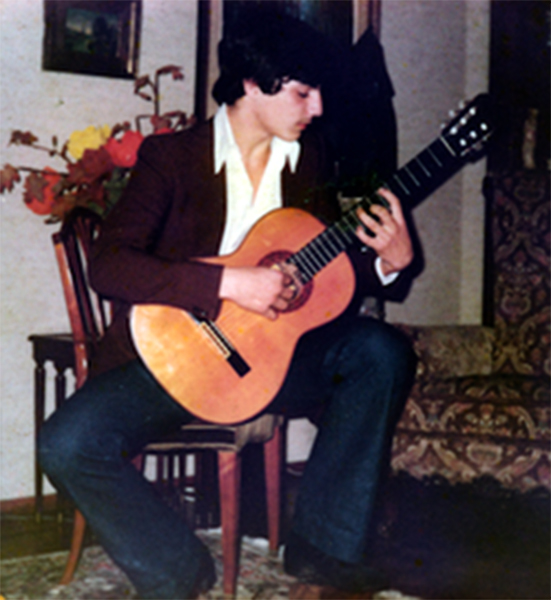

In his childhood, Cura learned to play the

piano by intuition, watching as his father interpreted Beethoven

and Chopin. Later he studied guitar, composition and piano,

and entered the School of Art at the University of Rosario.

By 12 he had already begun to direct choirs and orchestras.

Along the way, he specialized in martial arts and played rugby.

Then at 27 he began to sing. “Singing appears rather late

in my musical career. I discovered that I had a voice and

initially the investment seemed very logical: with this voice

I was going to be able to eat and to give food more easily to my

family than with composing. As crude as that sounds, I started

singing for purely economic reasons,” he admits and then explains:

“That which began as a blind date ended in a life-long relationship

but in the beginning I believed I was going to sing for only a few

years to relieve the situation, to pay the bills and pay for my

house. Finally, it turned into the full-time profession that

transformed me into what I am. There is a thing called destiny…I

cannot complain.”

And when things went badly for him, he didn’t

complain, either. In 1983 he wanted to enter the Teatro Colón

but a teacher at the audition told him, “You do not sing, you shout.”

The he gave classes in tae kwon do, body building, and worked in

a hardware store. In 1990 he took a second audition at the

Colón and finally they accepted him, but he decided to leave for

Europe. With his wife—whom he met at 16—and José, his first

son, Cura took a Pan Am flight toward Milan.

[NB: As most

of his fans are aware, Mr. Cura was accepted at the Colón in

1983 and rejected in 1990, after which he decided to move to

Europe. The reporter just got the dates mixed up but we

wanted to let you know the real story.]

A Stubborn Man

.jpg) -

I was always very stubborn. Like young children, each time

they get up in the morning it is not important to them what happened

the previous day, just that they are going to play again.

I believe I am like that. I was always convinced I had something

to say, I was prepared to say it, and was going to keep on saying

it until I finally found someone who would listen to what I had

to say and then this person would pass it on to others. It

is being eternally young beyond all mistakes and objections.

It causes one to want to continue forward with the same thing. -

I was always very stubborn. Like young children, each time

they get up in the morning it is not important to them what happened

the previous day, just that they are going to play again.

I believe I am like that. I was always convinced I had something

to say, I was prepared to say it, and was going to keep on saying

it until I finally found someone who would listen to what I had

to say and then this person would pass it on to others. It

is being eternally young beyond all mistakes and objections.

It causes one to want to continue forward with the same thing.

In 1995 [editor's note: he won in 1994],

Cura won the Operalia singing contest, presided over by Plácido

Domingo, and quickly became one of the most prestigious tenors in

the world, especially praised for his interpretive qualities.

A year later, he made his début in the role of Samson at the Royal

Opera House in London, a role that he continues to perform and for

which he received the Orphée d’Or and Echo Klassik

awards.

- What is important for you to interpreting

Samson et Dalila?

- One of the things in regards to this opera

is its use of force. Some fifteen hundred years before Christ

there was killing in the name of God, and 3500 years later, it is

the same thing. Humans still do not have the courage to take

responsibilities for their mistakes or their successes. If

we need to kill, the fault is with the other, and if we use God,

so much the better because no one can complain or say anything.

- And personally?

- This opera has a special aura because

it has been with me practically throughout my career. I have

it very well done, very well chewed, very studied, and very sung.

The character is the same in all works, the equation is different.

Every performance is like an act of love, a sexual act, and it is

the audience who is your partner at this moment. And you have

to ask yourself, “How much do I give to the artist?” The difference

between an audience who succumbs to the artist and one that does

not is enormous. It is like making love to a plastic doll.

- How do you prepare for your roles?

- The voice functions like the face of a

model. When you are going to do a photography shoot, you have

to treat yourself to more sleep so that you have the least ‘wrinkles’

possible. And on the day of a performance, if a singer tries

to rest everything so the voice can be as fresh as possible, that

is ideal.

- Why did you decide to live in Europe?

- I like Madrid, we have a most beautiful

house where I am able to have all the things I want in my life,

achieve all my whims.

- Do you have the tastes of a divo, eccentricities?

- Eccentricities, none. But, yes,

I give myself the things that I want. I have a wine cellar

in my home, with a pile of wine I have collected. I have a

pool, a gymnasium, the things that we have always wanted in the

way we like most.

Cura confesses that when he is alone in the

house he enjoys silence and he never sings in the shower.

He prefers to shop, to cook, and to taste wine.

- And you also like photography?

- Yes, I love it, and we are now negotiating

the release of my first book of photographs with a Swiss publisher.

I like news-photography, not posed photos, and take to the streets

with my camera to collect the testimony of the entire world.

I grab hold of my camera and get lost. I have ended up in

some screwed up neighborhoods and more than once have had to be

removed from complicated situations. I love to know the true

face of a town.

- Opera is often considered to be of the elite.

Is this something that bothers you?

- It is always spoken of as elite, but anywhere

in the world the ticket price to listen to an opera costs less that

the cost of tickets to the [sports] field. For many years

there was a tendency: people who liked classical music wanted

to feel exclusive, but that is stupid because the composers wrote

the music for everyone. They were simple people, but not easy

people. They were geniuses because they were simple, and this

trend to deify them became fashionable at the beginning of the twentieth

century, when these divisions were created for the purpose for with

which all divisions are created: “Divide and you will rule.’

When in fact there is only good music and bad music. There

is boring classical music and brilliant popular music.

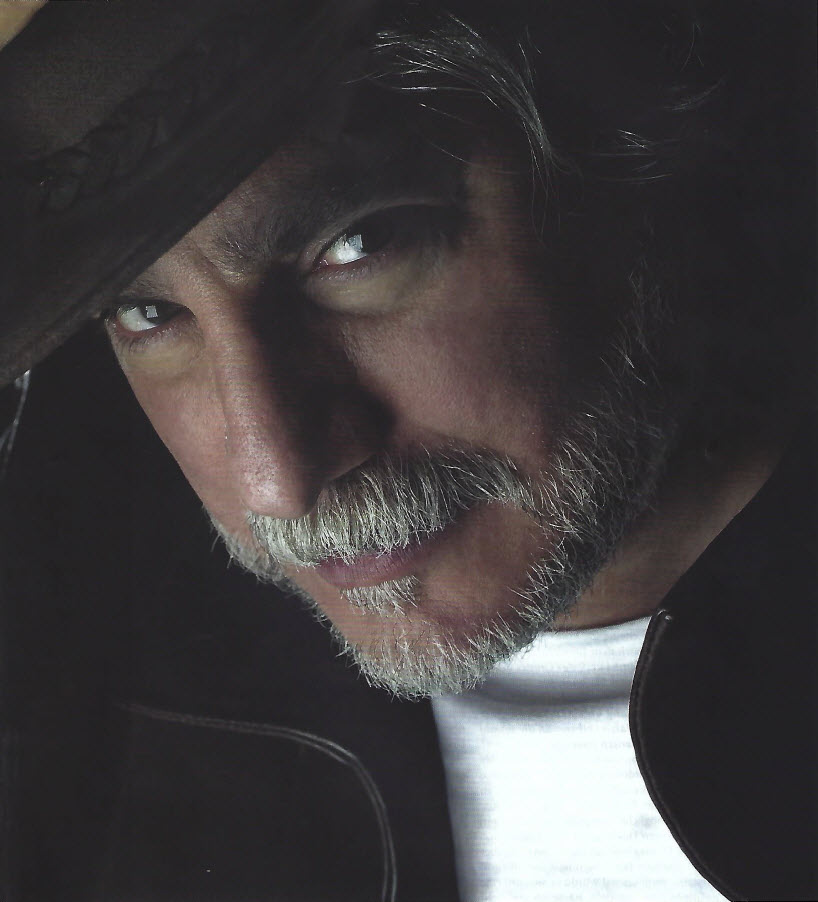

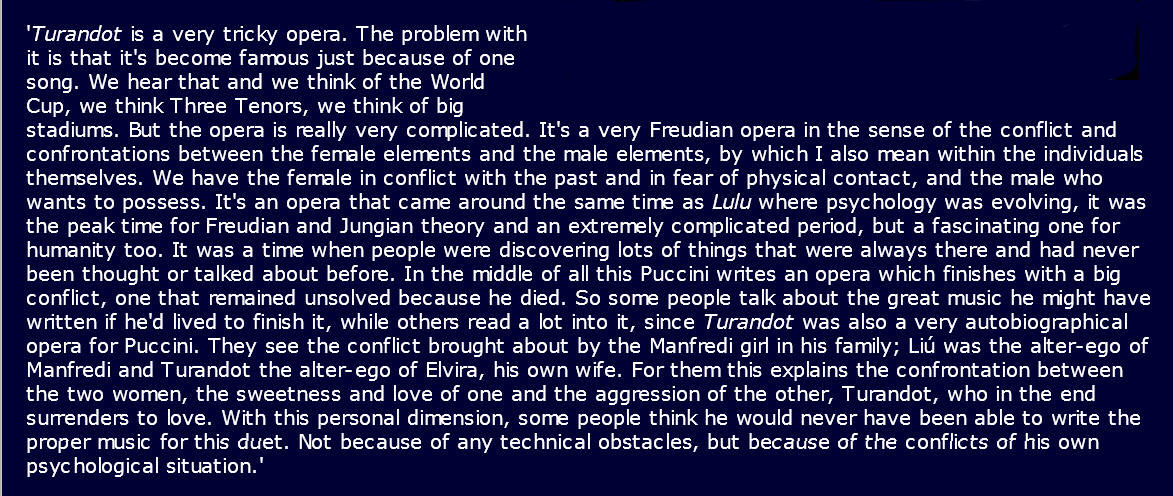

He Can't

be the Same Man, Can He?

The Independent

Michael

Church

12 April 2007

In 1993,

José Carreras celebrated his triumph

over leukaemia by starring in Verdi's

Stiffelio at Covent Garden. Two years

later, an unknown singer named José

Cura replaced him.

That

was Cura's launch: overnight he was

awarded a big recording contract, and

hailed as the "fourth tenor" and as

a new operatic sex symbol, and his meteoric

career began. Now he is back in that

role: the production is physically the

same, but since both he and director

Elijah Moshinsky have changed in the

intervening time, it will also reflect

that.

"Then

I was a naive young kid trying to fit

into the shoes of a tormented and complicated

adult," says Cura. "Now I am

closer to that character." Is his

voice changing? "A lot. It's getting

darker and darker, to a point where

some people think it's moving beyond

the tenor range. Certain characters

I cannot do now, not because I can't

[sing the role], but because the colour

of the voice wouldn't portray the psychology."

And

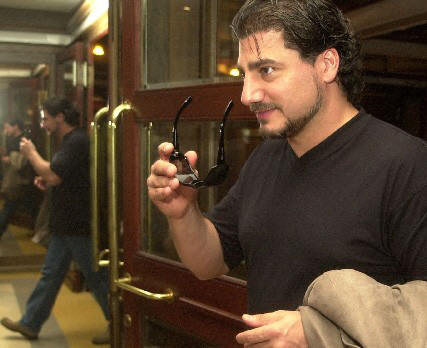

although he still exudes the lazy pantherish

charm that made his first interviewers

go down like ninepins, he's taken drastic

steps to obliterate that original image.

"All that stuff about the sonny-boy

sex symbol, those stories about the

fourth tenor - it was sending out the

wrong signals, and I was getting shot

at with the wrong weapons. I grew very

unhappy with how I was being sold, so

I dismissed my agent and set up my own

company to organise my work.

"I'm

44, and I started my career when I was

14 - I've worked very hard to become

a serious musician and a finished artist,

and now we've cleaned away the garbage.

Now I am accepted as serious artist."

He globetrots

as a conductor as well as singer, he's

staging his own touring production of

Pagliacci in Croatia, and he has had

a new CD and two DVDs out in the past

three months: point made, point taken.

José Cura Writes of Love

La Nacion

The tenor premieres

his own songs based on poems of Pablo Neruda

Saturday July 7, 2007

With

his performances in Samson et Dalila presented by

the Teatro Colón, José Cura gave ample evidence to the Argentine

public of why his name is where it is in the world of opera. Nevertheless,

and not to lose the habit of being pleasantly surprised, an important

moment still remains on his agenda before the tenor returns to Europe.

It is a question this time of the world premiere of his Sonnets,

based on the poems of Pablo Neruda, that take place tomorrow in

the program for the Mozarteum of Rosario, which is celebrating its

Silver Anniversary with a concert by José Cura and pianist Eduardo

Delgado in the Foundation Astengo. The two, acquainted through

the CD of Argentine music Anhelo, will offer a chamber

recital, including songs from the recording, works for solo piano,

and the pieces composed by Cura. With

his performances in Samson et Dalila presented by

the Teatro Colón, José Cura gave ample evidence to the Argentine

public of why his name is where it is in the world of opera. Nevertheless,

and not to lose the habit of being pleasantly surprised, an important

moment still remains on his agenda before the tenor returns to Europe.

It is a question this time of the world premiere of his Sonnets,

based on the poems of Pablo Neruda, that take place tomorrow in

the program for the Mozarteum of Rosario, which is celebrating its

Silver Anniversary with a concert by José Cura and pianist Eduardo

Delgado in the Foundation Astengo. The two, acquainted through

the CD of Argentine music Anhelo, will offer a chamber

recital, including songs from the recording, works for solo piano,

and the pieces composed by Cura.

The history of these Sonnets

was born in 1995, when José sang in Palermo (Sicily) in the Zandonai

opera Francesca di Rimini, based on the legendary

lover Romeo and Juliet. Someone—he never knew who—left a book

of Neruda poems in his dressing room with an anonymous dedication

that says, “For you, who sing of love, words of love.”

On opening the book, according to the tenor, the first thing he

read was the last sonnet that says “When I die, I want you hands

on my eyes” and he was so moved by emotion that the music was composed

almost at once in a single moment of inspiration. He continued

with “My love, if I should die and you should not” until the commitments

and the dizzying life of the singer on the rise forced him to put

all the beautiful ideas and sensation in a drawer not to be opened

for several years, until, in 2006, the composer firmly decided to

finish the project and to choose the sonnets that, he felt, still

remained to complete the cycle. The author of the dedication,

very romantically, has never been revealed.

In Buenos Aires, La Nacion met with

Cura and Delgado. The pianist referred to the work as personal

music whose harmonies declare a proper and elaborate language.

“They do not look like anything else. They are interesting

works and with their polyphonies and counterpoints, they are also

difficult. It gave me pleasure to work with them because they

demanded I study them and because I feel I can relate with José’s

musicality,” Delgado explained.

In turn, Cura added comments that

referred to the composition of the Sonnets.

-Are they composed for your own

voice?

They are written for a high baritone because

I consider the voice of a baritone the most beautiful one for chamber

music, as in that of the mezzo for a woman. The middle zone

is where the voice flows more sweet and less forced. This

reflects my own vocals: a dark voice with the ability to sing

high notes. It is not possible to sing them like normal songs.

They are intellectual, which means they cannot be learned by hearing

them, it is necessary to be able to read and to understand in depth

the music that, in reality, is a long duet of piano and song.

- How did you transfer the musicality

of the word to that of the singing voice?

-The poetry of Neruda awaken the

senses, is theatrical in an old-fashioned way. Each word is

loaded with theater and drama. The options were to write melody

accompany the words or to write music, but with the sensory wealth

that opens us up to Neruda’s fascinating world. The complexity of

the music is related to that of the text, so that it is not necessary

to listen to distill pure melody. One must concentrate in

the poems, leaving the melody to present itself alone.

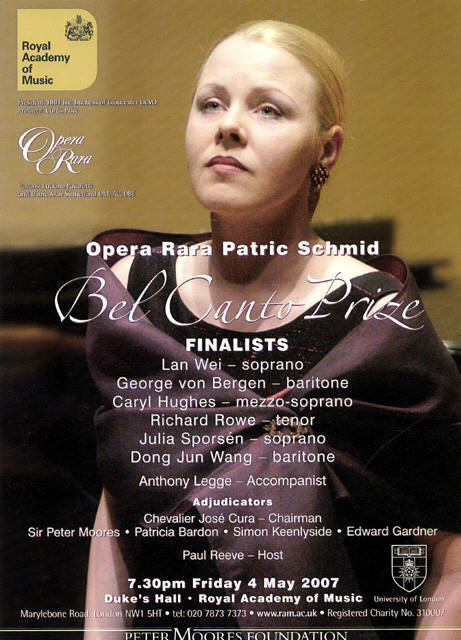

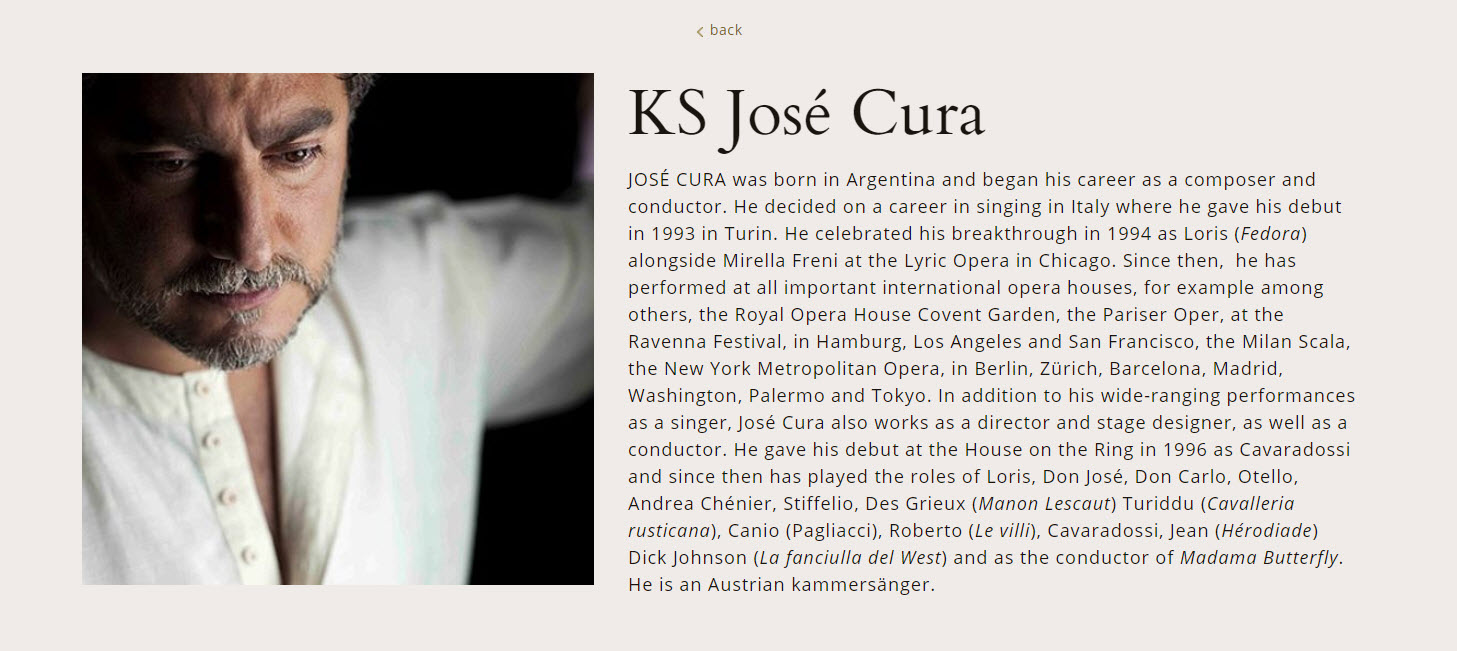

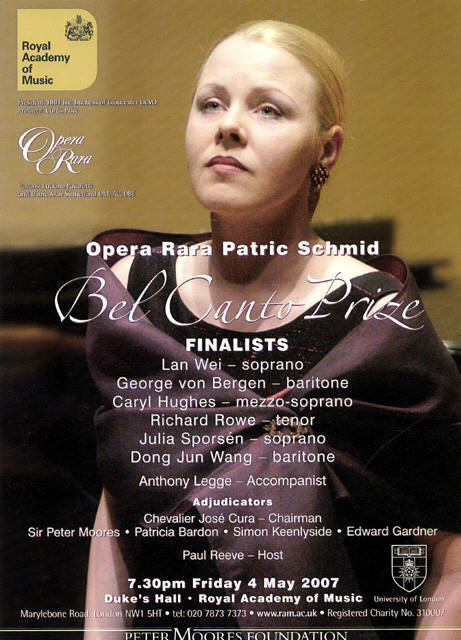

NDO is privileged to have as its

Patron, internationally renowned tenor and conductor

José Cura. Maestro Cura, originally from Argentina

and now based in Madrid, has a deep interest in finding ways

to help younger singers gain experience and so help further

their careers.

This is a unique

opportunity for music lovers from Devon and the UK, to enjoy

the passion, commitment and artistry that Maestro Cura brings

to everything he does. In addition to the Masterclass, there

will be a garden party Concert performance

of opera arias and ensembles given by all twelve singers in

the afternoon of May 7th; Maestro Cura will then present the

prize. On the morning of May 6th, Anthony Legge

(Director of Opera at the Royal Academy of Music) and

Alex Ingram, conductor and music coach, will

be bringing their expertise in working with opera accompanists

to a Repetiteurs' Seminar. Devon singers will have an opportunity

to take part in this seminar.

The performances will be held in

the charming Jubilee Hall of Stover– an independent school set

in its own 60 acres of beautiful grounds in the glorious Devon

countryside. Stover is situated on the edge of the Dartmoor

National Park, just a few miles west of the market town of Newton

Abbot and a mile from the main A38 carriageway between Exeter

and Plymouth.

“I truly

hope that New Devon Opera enjoys economic success

which will allow the company to develop in a strong

and confident way.

" José Cura

Opportunities in

the UK to see or hear international opera singer and conductor,

José Cura, are rare but on 6 May 2007,

Maestro Cura will come to Devon to give a public Masterclass

with twelve talented singers he has chosen – and who

will represent some of the best of today's young opera singers.

A compelling actor

and charismatic stage performer, Cura has been featured in numerous

telecasts of opera productions and concerts from venues around

the world. Blessed with a rich burnished tenor voice, mesmerizing

stage presence and abundant charm, José Cura has been thrilling

audiences since he first burst onto the international music

scene. His intelligent, insightful – sometimes controversial,

but always intense and unforgettable performances - have made

him a household name to opera lovers the world over.

But this success

did not come easily. As Cura himself puts it:

“I moved from Argentina

to Europe in 1991. I worked for two or three years in restaurants

– my wife worked with me, washing dishes – and we did many things

a lot of people wouldn't think about doing. We had a very hard

life. We lived in a garage for one year because we couldn't

pay the rent and we heated the garage with a small fire, with

me gathering wood in the middle of the night!”

It is this

memory that drives his desire to help promising singers to gain

the skills and experience needed to succeed in the notoriously

tough and challenging world of international opera. Working

together with New Devon Opera – the south west's

resident professional opera company, of which he is Patron –

the aim is to build this project to become a regular national

event in Devon.

This is a unique

opportunity for music lovers from Devon and the UK, to enjoy

the passion, commitment and artistry that Maestro Cura brings

to everything he does. In addition to the Masterclass, the re

will be a garden party Concert performance

of opera arias and ensembles given by all twelve singers in

the afternoon of May 7th; and, Maestro Cura will present a prize.

On the morning of May 6th, Anthony Legge (Director

of Opera at the Royal Academy of Music) and Alex Ingram,

conductor and music coach, will be bringing their expertise

in working with opera accompanists to a Repetiteurs' Seminar.

Devon singers will have an opportunity to take part in this

seminar.

The performances

will be held in the charming Jubilee Hall of Stover– an independent

school set in its own 60 acres of beautiful grounds in the glorious

Devon countryside. Stover is situated on the edge of the Dartmoor

National Park, just a few miles west of the market town of Newton

Abbot and a mile from the main A38 carriageway between Exeter

and Plymouth

An international star, José Cura has received many awards

and prizes for artistic excellence. In 1994, he was awarded

first place at the International Singers Competition (Operalia)

as well as the Prize of the Public; in 1997 he was awarded the

Abbiati Award (Italian critics' prize) for his performances

in two Mascagni operas - “Iris” in Rome and “Cavalleria Rusticana”

with the Ravenna Festival- and in “Il Corsaro” in Turin. A year

later, he earned the Orphée d'Or from Académie du Disque Lyrique.

In 1999, the Buenos Aires ' CAECE University awarded him the

distinction of “Professor Honoris Causae” and the city of Rosario

the one of “Citizen of Honour.” He received the ECHO award for

Sänger des Jahres from the Deutscher Schallplattenpreis in 2000.

In 2000, Cura was knighted “Chevalier de l'Ordre du Cedre”

by the Lebanese Government.

Cura was honored as the Best Artist of the Year from Grup

de Liceistes in Barcelona in 2001, received the Ewa Czeszejko

- Sochacka Foundation Award (Poland) in 2002, and the Sirmione

Catullus Prize honoring him as one of the great singers of opera

in 2003. In recognition of his artistry and in acknowledgement

of the great affection and high esteem in which he is held in

the country, José Cura was awarded “Citizen of Honour” by the

City of Vesprem, Hungary, in August, 2004.

Year 2005 proved a banner year for José Cura. In November,

The British Youth Opera (BYO) announced that he had accepted

the position of honorary Vice President of the company.

This appointment, made in recognition of Cura's dedication to

teaching, mentoring, and supporting young talent, adds his name

to a distinguished list of benefactors including such luminaries

as Dame Janet Baker, Dame Felicity Lott, and Bryn Terfel.

Cura also became Patron of New Devon Opera. The company,

established to promote and tour opera within Devon and the South

West of England, is a non-profit organization that promotes

charitable and educational productions and concerts.

In

December 2005, Cura became the second recipient of the City

of Piacenza-Giuseppi Verdi award in recognition of his contribution

to classical music as both singer and conductor. The award,

individually designed to honor the winner, is given annually

to an artist of international significance who has inspired

critical approval and audience affection. That Cura receives

the recognition so soon after its establishment is tribute to

his reputation as one of the greatest tenors of the age, his

artistry on the podium, his warm relationship with fans, his

personal support of young musicians and his on-going involvement

in charitable organizations.

Learning from a Maestro

By Laura Joint

World famous tenor José Cura comes to Devon to hold

a masterclass with 12 lucky singers.

Internationally renowned opera star José Cura will be in Devon

in May, to hold a masterclass with 12 singers.

The Argentinian-born tenor, now based in Madrid, agreed to

take the classes after becoming patron of professional touring

company, New Devon Opera. The opera company, based in

South Devon, publicised the project in 2006 - and more than

100 singers from all over the world have applied to be selected.

That number will be whittled down to around 25 for auditions

in London on 24-26 April. José Cura will then choose the final

12 who will be in the masterclass in Devon on 6-7 May.

It's hoped the José Cura Opera Project will unearth a new

generation of opera stars.

The public will be able to watch the classes at Jubilee Hall,

Stover School, near Newton Abbot on 6 May. Then, on 7 May, the

12 will perform mainly ensemble pieces at Stover School - in

front of an audience including the Maestro himself.

The tenor will present the singer who impresses him the most

with a special prize.

José Cura is in England in April and May, as he is performing

in the Verdi opera, Stiffelio, at the Royal Opera House in London.

Linda Hughes, chair of New Devon Opera, says it's a real

coup to bring José Cura to the county.

"This really puts Devon on the map," Linda told BBC Devon.

"People from all over the world have taken an interest in this."

Linda hopes that the event can be repeated in the future

- but on an even bigger scale. New Devon Opera was formed in

2004 and auditions for performers locally and nationally. It

is a not-for-profit charity.

In a classic case of 'if you don't ask, you don't get,' Linda

approached José Cura about the role of patron.

"I was speaking to him at the Royal Opera House and I asked

him. And he said yes!".

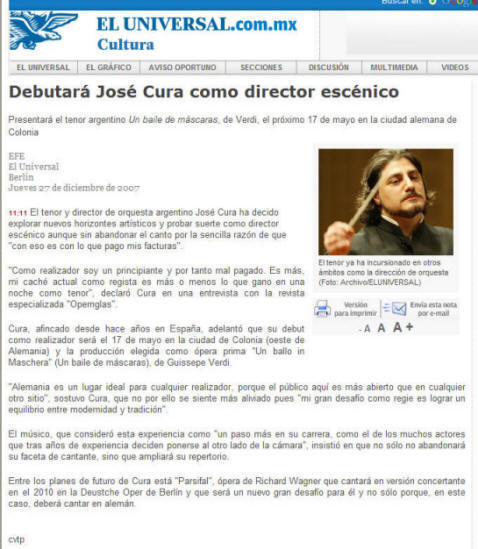

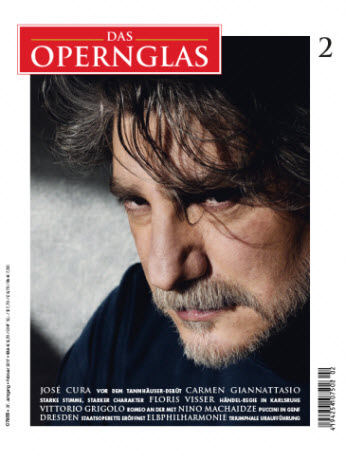

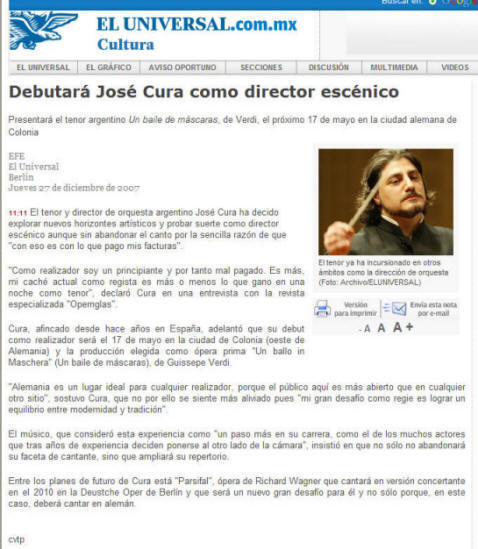

Debut of José Cura as Stage Director

EFE

El Universal

Berlin

Thursday December 27, 2007

(gist)

The Argentine tenor will direct Verdi’s Masked Ball next 17 May in

the German city of Cologne

Argentine tenor

and conductor José Cura has decided to explore new artistic horizons

and will try his luck as a stage director—but without abandoning

singing for the simple reason that “singing pays my bills.”

"As a director

I am a novice and therefore not paid well. In fact, my actual pay

as director for the entire production is more or less what I earn

as a tenor in a single evening," revealed Cura in an interview with

the magazine "Opernglas."

Cura, living for

years in Spain, makes his debut as director on 17 May in Cologne

(western German), and the production chosen for this initial effort

is the opera Un ballo in maschera (A masked ball) by Giuseppe

Verdi.

“Germany is an

ideal place for any producer, because the public here is more open-minded

than almost anywhere else,” maintains Cura, who nevertheless feels

comforted that “my big challenge as director is to achieve a balance

between modernity and tradition.”

The musician considers

this experience as “one more step in my career, just as many actors,

after years of experience, decide they want to be on the other side

of the camera,” but he insists that not only will he not abandon

his role of singer but he will also expand his repertoire.

Among Cura’s future

plans is Parsifal by Richard Wagner, an opera he will sing

in concert version in 2010 at the Deutsche Oper Berlin that offers

a major new challenge for the tenor--and not just because, in this

case, he must sing in German.

José Cura’s Debut as a Director

Der Standard

27

December 2007

(gist)

Hamburg - The Argentine star tenor and conductor José Cura now

tries being an opera director. On 17 May 2008, the 45-year-old will

make his directorial debut at the Cologne Opera with Verdi's "Masked

Ball."

"Of course, Germany is a wonderful place for

directors, as the audience here is really much more open than elsewhere,"

said Cura in an interview with the magazine "Das Opernglas." However,

this also serves as an excuse for the director who ignores the balance

between modernity and tradition: "That is for me the big challenge."

Acting Interests

Acting is of special interest to him, said the world-renowned singer.

"Directing is just the next step - similar to the famous movie actors

who, after years of experience with good directors, change sides.

In cinema it seems much more common and accepted than in musical

theater."

His main focus will continue on the singing,

assures Cura. "For a very simple reason: With the singing I pay

my bills." As a director he is a novice and is paid accordingly.

"My current job as a director - for the entire production - corresponds

more or less to what I earn as a tenor in one evening."

In the future the

singer will challenge himself with Wagner roles. In 2010, he will

sing “Parsifal” in concert at the Deutsche Opera. "This is my first

step to see how it goes." Wagner excites him on the one hand, but

frightens him on the other because of the language. (APA / dpa)

“The flag is

our identity: It is not the DNI* but the DNA of each

one of us.”

La

Capital

June 2007

José Cura says

that singing at the Anniversary Celebration of the Monument

was something very special. The tenor from Rosario,

who now lives in Europe, admitted that he felt flattered

by the call.

Rosario opera

singer José Cura joined in the festivities marking the

50th anniversary of the National Monument

to the Flag with a rendition of the “Canción a la bandera”,

which is an aria from Héctor Panizza’s opera “Aurora”.

Visibly moved, the tenor, who lives in Europe where

he has forged a solid career for himself, talked with

La Capital, confirming the saying that your homeland

is in essence your dialog with the land of your childhood:

“When I close my eyes, the first thing I see is my childhood

home, the neighborhood of those early years”, the artist

confessed.

Applauded

by the critics for his interpretations of Giuseppe Verdi’s

“Otello” and Saint-Saens’ “Samson”, Cura is also recognized

for being the first artist to have sung and conducted

the same work simultaneously as well as being the first

to combine vocal with symphonic performances in the

same concert. Applauded

by the critics for his interpretations of Giuseppe Verdi’s

“Otello” and Saint-Saens’ “Samson”, Cura is also recognized

for being the first artist to have sung and conducted

the same work simultaneously as well as being the first

to combine vocal with symphonic performances in the

same concert.

Emphatic, commanding

and loquacious, Cura steps for a moment out of his role

of operatic artist with international stature and enters

onto the path of confession admitting that to sing under

the circumstance that brought him here is somewhat different.

--What does

it mean to you to sing at the Flag Monument?

--To sing the

“Canción a la bandera” at the Monument is a bit overwhelming.

It’s not an ordinary concert; it’s about this place,

this particular spot and the song of it. There can be

nothing any more intense than that.

--Does this

place bring back memories for you?

--It’s not only

about memories but also about a sense of identity. The

Flag Monument is number one in what one identifies with

as a Rosarino. Perhaps number two is Newell’s and Central….After

having sung “Canción a la Bandera” in England, in Japan

and in Australia, it is something else altogether to

sing it here.

--What does

the flag mean to an exile?

--No, not an exile

because that implies a person who leaves with a kick

in the backside, so to speak. This man is not an exile

but an emigrant. Just as our grandparents came here

from far away in search of good fortune, many of us

left from here to go far off in search of ours. And

the flag is a means of identification, it’s our identity,

and it isn’t even just the DNI—it’s the DNA of each

one of us.

--Eight years

ago, you sang in this very spot before a crowd, and

we were not able to find out what kind of aftertaste

that experience left. What happened on that occasion?

--We were expecting

5,000 people and 40,000 came. It was an extraordinary

event, full of warmth and affection. It’s a tremendous

memory.

--When you

close your eyes and think of Rosario, what do you see?

--The first thing

I’m likely to see when I close my eyes is my childhood

home and the neighborhood of those early years. It’s

a place that has changed very much. Clearly, thirty

years have passed….

--The reason

for this visit to Argentina is the presentation of other

programs, like those you are going to give with the

cast from the Colón at the Coliseo of Buenos Aires Theater.…

--No. The initial

reason for this visit was the celebration of my parents’

fifty years of marriage, an anniversary that coincides

with that of the Monument. Later, it became known that

I was coming since it is practically out of a question

that no one is going to find out when one moves about,

and from there, the invitations began to arrive. In

this case, they are especially appreciated because taking

part in this celebration is something special. Afterwards

the one from the Colón came up and the concert in the

Mozarteum here. In the end, I’m working more during

this vacation than I do when I’m at home.

--What has

been going on with your “Aurora” CD?

--That was a disc

dedicated to my country which, to be precise, does begin

with the “Canción a la Bandera”. I recorded that CD

in 2001 and dedicated it to Argentina, but it was never

sold in the country. We are not managing to set up agreements

with any distributor. It was a CD dedicated to this

country and sold throughout the world, but here, it’s

sad to say, no one knows about it. To mark the occasion

of the 50th anniversary of the Monument,

the City of Rosario has entered into an agreement with

my company to buy 5,000 discs at cost. We are not making

anything, but at least, in a symbolic way, it will be

found at this commemoration, when it should have been

here all along and should have sold thousands of copies

simply because it is dedicated to Argentina, regardless

of whether the artist, who made it, is liked or not.

When a disc is dedicated to a country, it is (really)

dedicated to its people. Dedicated to my fellow Argentineans,

it is a CD to which they have no access. Market considerations

take precedence over sentimental ones. Let’s hope that

5,000 copies are not enough.

*DNI-Documento

Nacional de Identidad

Translation: Monica B.

|

A Conversation with José Cura

Entre Notas

María Josefina Bertossi

When José Cura came down punctually to the

lobby to give us his final interview before returning to Europe,

I thought it was gracious of him not to have canceled after the

effort of the previous night’s concert when he sang while suffering

from an untimely cold (for a singer, a cold is always untimely).

Besides, it was a very cold 9 July (Rosarinos hardly remember when

it was really cold) and many expected snow. I will never forget

when it snowed in Rosario a few days before my entire family was

involved in a car accident and we saw the snow on the windows of

the hospital, recalled the Rosarino musician (singer, director,

composer) who now lives in Madrid but works in capital cities around

the world.

“Have you ever tried to pick a flower

with a glove?” was the first thing we heard from José Cura

from the stage. The opening question was an attempt to explain

how it feels for a musician to sing with a cold and, in addition,

to share the recital and the respiratory affliction with the pianist,

Rosarino Eduardo Delgado, also ill with a cold.

The audience filled the auditorium of the Teatro

Fundación for the concert on 8 July, the main event of the 25th

anniversary of the Mozarteum of Rosario, which had been announced

as a program of chamber music, a difficult assignment considering

the health (of the artists) since this repertoire needs vocal subtleties,

but we can attest that the artist carried it off with experience

that comes from the position, interspersed with enjoyable and sincere

comments.

“Last night I took a beating and this morning

I rose voiceless. Anyone who isn’t in this career has no idea

of the significance of singing with bronchitis. I did well

and believe those who saw it liked it,” Cura said with satisfaction.

There were those who hoped you would sing opera

even though chamber music had been announced.

The program said chamber music. I

would love to do all of my concerts this way. I do not enjoy singing

arias in concerts because opera in concert is monastic and the audience

always expects me to sing the same thing. Besides, opera cannot

be done with just a piano and for a concert as important as this

anniversary it had to be a chamber concert with piano.

The auditorium of a theater can be a good thermometer

to measure the relationship between an artist and the public, and

it is there that we listened as some talked about this singer.

José Cura is the full name of an international artist, but those

who knew him in Rosario, in Fisherton, and from childhood they have

called him what they always called him: José Luis.

José was designated by the exigencies of

the program space because José Luis is too long. Only in Rosario

do they call my José Luis.

The concert represented the world-wide release

of Sonetos, a work based on the verses of Pablo Neruda with

music by José Cura. The composer explained that once

in a dressing room somebody left him a book of poems by Neruda,

which he fortuitously opened to the page of the sonnet that begins

“When I die, I want your hands on my eyes.”

The premiere was not assured, however, since

authorization from the heirs of the Chilean poet arrived only four

days earlier.

Here in Rosario we saw you and we listened

to a singer, composer and director. How difficult is it on

the international level to impose the role of director and composer

on the figure known as a singer?

I never impose it. I propose.

Those who like the proposal accept it, those who do not, don’t.

I conduct a lot and in very important locales such as the Vienna

Opera and when you direct the Wiener, you conduct one of the significant

orchestras in the world, the same is true in London with the London

Symphony. There is never this sort of question because

when one stands in front of the orchestra for the first three minutes

the musicians see the tenor but then no longer, because to move

forward without a professional musician [standing on the podium]

would not be possible. The preconception comes from the press,

which does not understand and uses tenor as a bad word. To

say someone is a tenor is like saying that she is a woman rather

than a feminist, like referring to a stupid individual with no rights.

The buzz surrounding the concert was the announcement

of the ‘music’ of José Cura.

Because of it, the highest points in the

entire night were the sonnets, twenty minutes of music of very strong

intensity and that says a lot. When you write something people

have not felt, makes no sense to them, they start fidgeting and

begin coughing. Therefore, it was very emotional, and one

must not forget this was a premier, that while the audience was

listening, and it is complicated [music], they were already analyzing

it and enjoying it. There was a lot of work (in composing),

hard work with theatrical awareness. Every harmony and every

melodic turn tried to continue the poetry of Neruda.

In our city, there is a lot of music and many

musicians who feel dissatisfied with what they can and cannot do.

There is something everyone needs to know:

nobody comes to seek you out, and this is true not only in Rosario

or in Argentina: it is that way in the world. Youth

has a tendency to say ‘I am the best in the world but no one knows

it.’ I know many cases like that, both colleagues and students,

who come to me and say ‘Maestro, what do I have to do?’ and I tell

them they must go out and bang on doors, and they say to me ‘But

what happened that made you so lucky?’ Luck? I

have spent more than thirty years doing this and only in the last

ten or fifteen years have I begun to see the fruit. Recently,

in the last five years of my life, I have been transformed by an

event that is very easy to obtain—the event of maturing.

Sometimes, someone will ask me how it feels

to be famous and I say nothing at all, because it is so easy to

become famous. Nowadays, with the mass media, being a celebrity

is almost free. The difference is to achieve the sort of fame

that is transformed into greatness.

Sometimes the decision to leave or to stay

can be very difficult.

Emigration is always difficult. Even

though now it is easier for us than for our grandparents, that does

not stop it from being traumatic. When you move to a country

where nobody greets you, nobody knows you, and when you present

your work visa they look at you badly simply because you are Argentine

or because you are a foreigner, and there is nothing you do to avoid

it, and that it what happened to my wife and me. There were

many people who told me not to leave but if I had a contract I would

not have gone. For example, in Buenos Aires some singers

asked me how they were singing and I said good. “Well, then,

if you have a contract you can send it to me.” No, it doesn’t work

like that.

The concert ended with “Aurora” by Hector Panizza,

the same aria that was sung together with the audience at the Monument

to the Flag, the same one which he also occasionally surprises the

English audiences. Despite the respiratory problem that appeared

in the last note of the aria, when the audience asked one more from

him, Cura , with humility, agreed to one last one.

You have a work dedicated to the Malvinas.

What has happened to it has not be produce?

I knocked on two or three doors and they were

not opened, nobody seemed interested in it. Perhaps it was

not the moment. When I wrote it in 1984, I was 22 years old

and we were entering a democracy. It is a work for two choirs,

with the dream being there would be an Argentine choir and an English

choir, quartet soloist, a children’s choir, an orchestra—a very

big, very expensive work. I wrote it in ’84 and there it remains,

and if some day I decide to do it perhaps I will have to revise

it, because many years have passed and with them a lot of experience

has been gained, or maybe not, because perhaps it would be nice

to show what a boy of 21 wrote at that age.

Interval Drink with José Cura

Classic FM

Sarah Kirkup

May 2007

What are you drinking?

A Spanish red wine from my beautiful cellar!

You're the patron of New Devon Opera...

The point of the project is to create an operatic activity in

Devon. We have auditions this April and, depending on the quality

of the singers we get, we'll see how far we can go.

Why do you want to help?

I believe in the continuation of the human species! Also, I

am known for being a rebel, and it would be ridiculous to have fought

all your life to transmit your opinions and then to die without

leaving your legacy.

You're in Stiffelio at Covent Garden from

20th April...

With Stiffelio, I am allowed to be a dark character, and I like

that. The one-dimensional thinking of most tenor roles is exhausting

- it's so limiting having to behave like the beautiful lover all

the time!

Acting's important to you...

You have to be believable. The best compliment I had was at

the end of Otello, when an epileptic came up to me and said: "I

saw myself in you". I had studied for a long time the reactions

of epileptics; the ability to observe has to be the main quality

of any actor, I think.

You conduct as well...

Singers respond well to me as a conductor because if there's

anyone who knows what the hell they're going through, it's me. I

conduct and sing at the same time, but only encores; a whole concert

would be a killer!

What's your next ambition?

I'd love to sing under the baton of Simon Rattle. I like his

fresh approach to music.

José Cura:

Titan of the Opera

Le Nueva

He has just arrived in

the country to dazzle us with his talent. This Argentine

tenor, who has already triumphed in Europe, will sing today

in Rosario.

[gist translation]

José Cura is one of the tenors in greatest

demand on the international stage and also one of the most popular

figures in classical music, but he does not agree with such high

praise. His is a multifaceted talent (singer, conductor, composer,

guitarist, régisseur and businessman), impelled by a spirit always

eager for creativity and challenges, leading him on a journey toward

artistic satisfaction. Always on the edge of frenzy from this

fascinating life, Cura’s temperament seems to have been forged to

enjoy facing risks, as a real titan, and not in vain has it been

written that his is one of the greatest voices of the century.

For all that, and in spite of his youth, José Cura has already joined

Olympus as one of the mythical singers [sacred monsters] of the

21st century.

An anticipated return home

He returned to Argentina, like one of our more

prodigal sons, for a concert production of the opera Samson et

Dalila by Teatro Colon, but most of all to his audience, to

their affection, and to his family. “After 16 years in Europe,

my house, in a physical sense, is no longer in Argentina.

But my feelings, my memories and my most intimate experiences, these

will always continue to remain in my country. I am happy to

return and meet again with the people with whom I grew up in an

artistic sense. I want to see the countrymen with whom I was

lucky enough to share the ‘kindergarten’ of the stage,” recounted

José in a talk in Berlin, Germany, not long before he returned home.

And then, as it could not otherwise be, speaking of reunions inevitably

means speaking of memories and the conversation, with Cura showing

a less familiar side, could not help but begin with his beloved

hometown, Rosario.

Memories of Rosario

“The oldest images I retain of Rosario,” he

recalls, “are the first two or three days of primary school.

I do not know if that was in the LaSalle or San José School, because

after three days my parents withdrew me to enroll me into a new

school, one that had just opened by the brothers of Saint Patrick

of Ireland. We were the first class. There were barely

two rooms and a patio. My class was also the first class to

graduate. Today it is a great school, one of the biggest in

Rosario. The last time I was in Argentina, in 1999, I visited the

school, I met with the students and I encountered a couple of my

former companions. So there is where I begin my memories of

Rosario, in the little school of St Patrick. In reality so many

years have passed…and it is only now when I return that I perceive

this passing of time.” The imaginary route soon pass by his

old house near the river and the second one in the first residential

district of Rosario. Almost immediately, and understanding

the strong connection that joins them, music arrived and, of course,

with it the beginning of the history whose future chapters would

cause him to do nothing less than conquer the world. “Music

always formed part of my family. My father played piano well

enough. I have a very clear image of when, as a boy, I watched

him, seated at the piano, playing Chopin and Liszt. Then he

tried to imprint on me his own story as a boy, sending me to study

piano with a teacher in the neighborhood. But the initiative

did not work.” After a few months, the teacher dismissed his

young student with a brief note sent to his parents, in which he

explained, sadly, that it would be best to wait for a time when

an interest [in music] developed in José that had, to that moment,

not been demonstrated, and at the same time he recommended looking

for a hobby that appealed to the young man, because musical sensitivity

did not seem strong in him. “It was probably true at that

time, and the best example was that, from that moment, I began to

devote myself to rugby.”

Musical Beginnings

But when did he discover his extraordinary

vocation in music and what was that cause that permanently awoke

his sensibilities? Oddly and without warning, that event was

the result of an examination to enter secondary school. “I

was there with one of my best friends. He played his guitar,

the Beatles were fashionable, and he created a lot of interest.

I learned to play immediately and the experience awoke the calling

that had been sleeping within me.” This was the friend who

gave him his first set of tools. Soon, his father contacted

Ernesto Bitteti (an old family friend), and Bitteti recommended

a professor with whom to study seriously. That began the history

with the guitar. “With my exuberant and extroverted personality,

I was like a time bomb. I learned to play well enough, although

always somewhat hampered by my very large hands…the things were

causing me quite a lot of work but I managed to have good results.

The guitar, though, very quickly made me feel small, not in a technical

sense but in the fact of it being a very introverted instrument.

For that reason, I entered the Conservatory in Rosario to study

conducting and composition.”

One of his teachers—who at the time was the

director of the conservatory—gave him the advice that changed his

life forever: “His comment determined who I am today.

He said to me: To become a better conductor and composer, you will

have to study singing.’ Indeed, following his advice I began

singing opera and ended up becoming a singer.” Everything

that happened after that is more or less well-known history; in

1983 he auditioned for the Teatro Colon, in 1991 he left for Europe,

where success and fame waited for him with open arms and rewarded

him for years of sacrifice in pursuit of his dream.

Today, and for some time, José Cura has been

one of the biggest names on the international music scene.

He is an exceptional professional who believes art is a profound

path in life.

“One of the characteristics of classical music

is that it is one of the few forms of art that remains, between

one person and another, a single thing: to the work of art

itself. We interpret that work live, without networks and without

lies. That artisan concept is probably the most important

aspect of music and, in my opinion, why it continues to work, although

as a spectacle it may be a little anachronistic. It is an

art of skin and bone, fact with flood, sweat and tears, and for

that reason it is an expression that stays alive. It is my hope

that all people, at least once in their lives, are touched by this

sensation, so powerful and so extraordinary.”

Love of Cerulean Blue and White

In one of his latest disks, called Aurora,

José Cura included a special dedication to ‘his country’ and printed

the Argentine flag on the cover. After launch of that record

(2002) Cura said, “I want my people to know that, for the entire

world and with much pride, José Cura is an Argentine tenor.”

Interview with José Cura

LaPorta Clássica

Ofèlia Roca

GIST TRANSLATION

Ofèlia Roca:

What is the daily life of an opera singer like?

José Cura:

Pretty much that of any other

person, I imagine. However, since I am a very atypical case,

I cannot offer a very reliable opinion. Perhaps a singer who dedicates

himself only to opera has a more orderly life, more aseptic in the

sense that he can take better care of himself. Personally,

since I devote myself to many things such as conducting orchestras,

composing, and running my company, my life is quite complicated.