LaNacion article June 2007

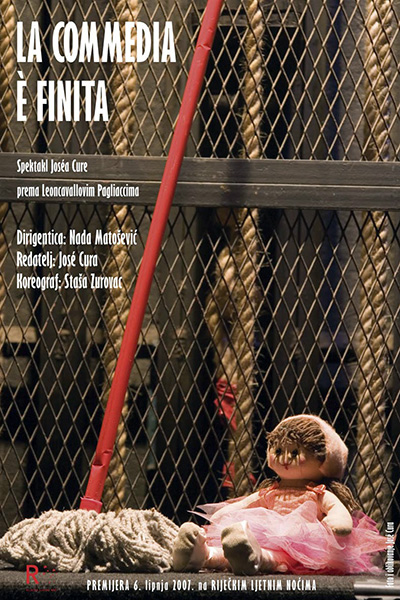

José Cura, the Return of the

Prodigal Son

One of the main items of interest

in the current classical music schedule of the city of Buenos Aires is

without a doubt the return of one of its prodigal sons, the Rosarino

tenor José Cura, after an eight year absence from the country. Living in

Europe for the past 16 years (currently in Spain), Cura’s name is

synonymous with success in portraying the dramatic characters of the

operatic repertoire, something which naturally turns him into one of the

most sought-after tenors in the world and one of the most popular

figures in his field. It also doesn’t hurt that on top of a phenomenal

voice, José Cura has an excellent physique for his type of role as well

as an exceptional professional foundation, which is both complete and

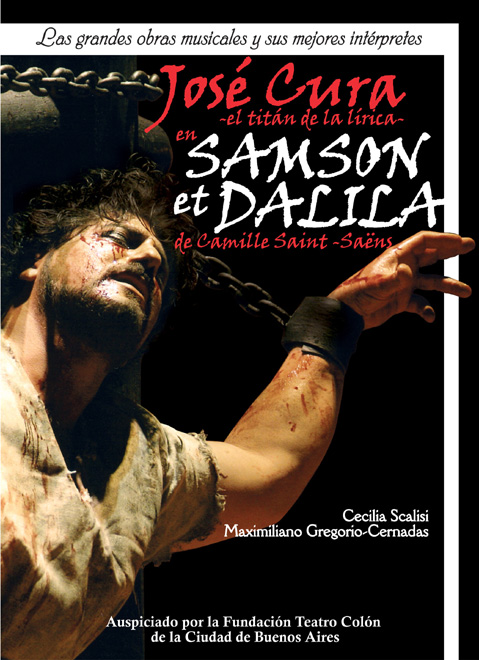

multi-faceted. The arrival in Buenos Aires of one of opera’s most

dazzling international opera stars puts the seal of the best in the

world of opera on the Teatro Colón’s season with a role that is

custom-made for him: the character of Samson in the Romantic-era opera

“Samson and Dalila”. Together with Cecilia Díaz and the cast, chorus and

orchestra of the Teatro Colón, the tenor will appear tomorrow evening at

8:30 in a concert version at the Coliseo.

The Titan of Opera

In

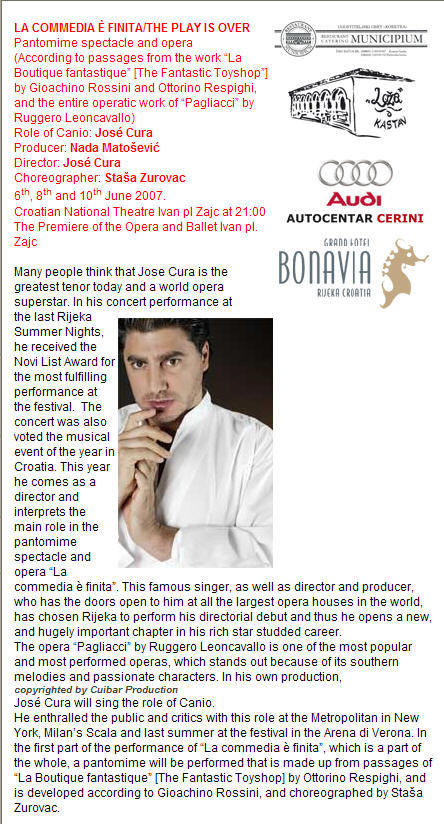

the fifteen years of his successful international career, José Cura has

frequented not only the most prestigious halls and theaters in the

classical music world (Met, Covent Garden, LaScala, Opera National in

Paris, Staatsoper in Vienna, Hamburg and Zurich, and the Deutsche Oper

in Berlin among others) but has also been present on remote stages, has

visited countries far removed from the traditional circuit, has

conquered exotic audiences as to opera and untiringly carried the art of

music and theater to inconceivable corners of the world. At his side

sing the most glamorous divas and direct the most celebrated conductors.

Parallel to his intense activity in the theater (as conductor, singer

and régisseur), he exploits his ample qualities as communicator and

showman with surprising ease, offering recitals and shows—some of them

on outdoor stages in front of thousands of people—in which he combines

singing with orchestral conducting (in an original format he himself

calls ‘half and half’), something that has earned him both the criticism

from the most conservative sectors of the music media and the admiration

of his fans, as well as an unusual popularity for an artist in the

classical genre. In

the fifteen years of his successful international career, José Cura has

frequented not only the most prestigious halls and theaters in the

classical music world (Met, Covent Garden, LaScala, Opera National in

Paris, Staatsoper in Vienna, Hamburg and Zurich, and the Deutsche Oper

in Berlin among others) but has also been present on remote stages, has

visited countries far removed from the traditional circuit, has

conquered exotic audiences as to opera and untiringly carried the art of

music and theater to inconceivable corners of the world. At his side

sing the most glamorous divas and direct the most celebrated conductors.

Parallel to his intense activity in the theater (as conductor, singer

and régisseur), he exploits his ample qualities as communicator and

showman with surprising ease, offering recitals and shows—some of them

on outdoor stages in front of thousands of people—in which he combines

singing with orchestral conducting (in an original format he himself

calls ‘half and half’), something that has earned him both the criticism

from the most conservative sectors of the music media and the admiration

of his fans, as well as an unusual popularity for an artist in the

classical genre.

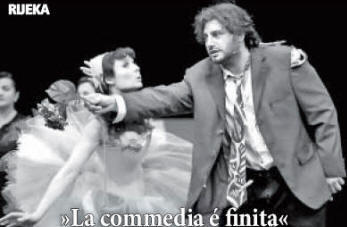

When José Cura began to be

mentioned on the front pages of the music media of the world, the

legendary figure of Samson was among the first roles to be associated

with the name and image of the Argentine tenor. Not only the qualities

of the timbre and the character of his voice, but also the exuberance of

his personality, his charisma and imposing stage presence permitted him

to be proclaimed—along with other great characters that he portrays with

equal empathy such as Otello, Canio, Don Carlo and Turridu—the ideal

interpreter of the biblical hero for several generations.

Some years have elapsed since

then; quite to the contrary of what often happens with a career that

takes off too quickly and with excessive fanfare only to become

exhausted by the media frenzy, all the predictions that accompanied José

Cura’s spectacular international rise have come to fruition in a career

beyond measure. In the following interview, the tenor refers to

different interpretative aspects of the role of Samson.

---What does one do about the

voice with respect to the traditional classification for Samson?

---If one would like to interpret

Samson in the spirit which is strictly understood as stylized French

music, in a historic sense, we would have to start with a voice that I

would not say is light but one with much less attack. It is very

different to do the role as it was conceived in around 1890. If we want

to, on the other hand, perform a modern Samson in light of the acoustic

problems and issues that we live with, the difference in the conception

as to the vocal aspect is enormous. More than relegating the role to a

classification based on the number of decibels produced, I prefer to

think of it on the basis of psychological coloring which is (to

be sure) a determining factor in the profile of the character.

---What are those acoustic

problems?

---The size of the theater today

is enormous. Then, there is the fact that the orchestra sounds very loud

due to the harmonic density of the modern instruments. A third point,

(and) a more dramatic one, is the rise of the diapason. The

majority of the operas which we perform today were written between 1800

and 1900. During that period, the diapason oscillated between 432

and 435 cycles, which means that, when we compare it with the

diapason that we use today, which is almost at 445, even up to 450

cycles, we have an increase in the tone by a third, even up to a half

tone. In short, this has caused an important modification in how we sing

as compared to the past. The logic of these conditions causes the

vocalizing (singing) of certain dramatic characters to be awarded to

voices which are much stronger and more robust.

---With respect to the

tessitura in which Samson is written, it is for a dark and baritonal

tenor who sings most of the opera in the middle register (medio-grave).

How do you decide the delivery of the high notes over the orchestra and

chorus?

---With a high note that has much

density (spessore), that is broad and large. We are talking about

a mythological hero who bases his entire legend on his physical power;

therefore, it would be ridiculous for the character to sing these notes

with the same sound value as, for example, a high note of the tenor in

“La bohème”. The more beautiful and correct the sound is, the more it

lacks dramatic intensity. This is the great vocal challenge of Samson

and of all the roles of the dramatic tenor in general.

---What is your perception of the

character with respect to vocal brilliance?

---Samson has clearly defined

moments in which he is able to shine for very different reasons. In the

first act, he is aggressive, a warrior of the Old Testament. In the

second act, the aggression changes to sensuality and extreme insecurity

in relation with himself, with God and with the feminine. In the third

act, which is spiritually the most interesting, is where Samson

redefines himself. In the entire first part of this act, Samson ought

to sing media voce. In the second part this changes on the other

hand, and we have again another type of singing. It is the moment of

redemption understood within the framework of a culture that existed

1500 years before Christ. The possibilities to shine are extensive and

manifold.

---Does this role give you a

feeling of satisfaction?

---Very much so! Samson is one of

the roles that I am indebted to the most for really making me shine on

stage. He is one of the characters that have given me the greatest

satisfaction throughout of my career.

Translation: Monica B.

A

Conversation with José Cura

María

Josefina Bertossi

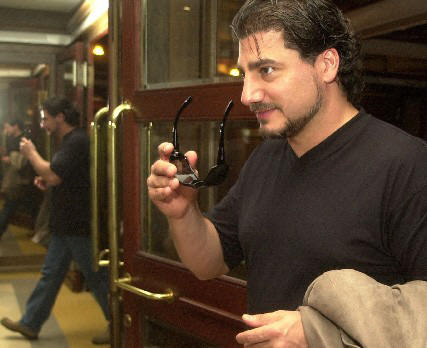

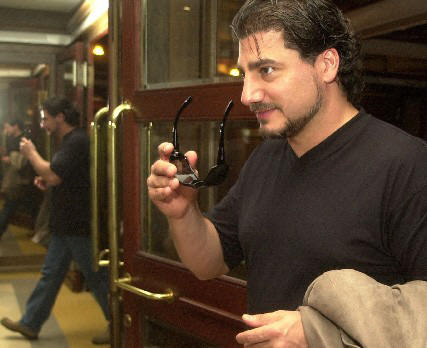

When

José Cura came down punctually to the lobby to give us his final interview

before returning to Europe, I thought it was gracious of him not to have

canceled after the effort of the previous night’s concert when he sang while

suffering from an untimely cold (for a singer, a cold is always untimely).

Besides, it was a very cold 9 July (Rosarinos hardly remember when it was

really cold) and many expected snow. I will never forget when it snowed

in Rosario a few days before my entire family was involved in a car accident

and we saw the snow on the windows of the hospital, recalled the

Rosarino musician (singer, director, composer) who now lives in Madrid but

works in capital cities around the world. When

José Cura came down punctually to the lobby to give us his final interview

before returning to Europe, I thought it was gracious of him not to have

canceled after the effort of the previous night’s concert when he sang while

suffering from an untimely cold (for a singer, a cold is always untimely).

Besides, it was a very cold 9 July (Rosarinos hardly remember when it was

really cold) and many expected snow. I will never forget when it snowed

in Rosario a few days before my entire family was involved in a car accident

and we saw the snow on the windows of the hospital, recalled the

Rosarino musician (singer, director, composer) who now lives in Madrid but

works in capital cities around the world.

“Have you ever tried to pick a flower with a glove?”

was the first thing we heard from José Cura from the stage. The opening

question was an attempt to explain how it feels for a musician to sing with

a cold and, in addition, to share the recital and the respiratory affliction

with the pianist, Rosarino Eduardo Delgado, also ill with a cold.

The audience filled the auditorium of the Teatro

Fundación for the concert on 8 July, the main event of the 25th

anniversary of the Mozarteum of Rosario, which had been announced as a

program of chamber music, a difficult assignment considering the health (of

the artists) since this repertoire needs vocal subtleties, but we can attest

that the artist carried it off with experience that comes from the position,

interspersed with enjoyable and sincere comments.

“Last night I took a beating and this morning I rose

voiceless. Anyone who isn’t in this career has no idea of the significance

of singing with bronchitis. I did well and believe those who saw it liked

it,” Cura said with satisfaction.

There were those who hoped you would sing opera even

though chamber music had been announced.

The program said chamber music. I would love to do

all of my concerts this way. I do not enjoy singing arias in concerts

because opera in concert is monastic and the audience always expects me to

sing the same thing. Besides, opera cannot be done with just a piano and

for a concert as important as this anniversary it had to be a chamber

concert with piano.

The auditorium of a theater can be a good thermometer

to measure the relationship between an artist and the public, and it is

there that we listened as some talked about this singer. José Cura is the

full name of an international artist, but those who knew him in Rosario, in

Fisherton, and from childhood they have called him what they always called

him: José Luis.

José was designated by the exigencies of the program

space because José Luis is too long. Only in Rosario do they call me José

Luis.

The concert represented the world-wide release of

Sonetos, a work based on the verses of Pablo Neruda with music by José

Cura. The composer explained that once in a dressing room somebody left

him a book of poems by Neruda, which he fortuitously opened to the page of

the sonnet that begins “When I die, I want your hands on my eyes.”

The premiere was not assured, however, since

authorization from the heirs of the Chilean poet arrived only four days

earlier.

Here in Rosario we saw you and we listened to a singer,

composer and director. How difficult is it on the international level to

impose the role of director and composer on the figure known as a singer?

I

never impose it. I propose. Those who like the proposal accept it, those

who do not, don’t. I conduct a lot and in very important locales such as

the Vienna Opera and when you direct the Wiener, you conduct one of the

significant orchestras in the world, the same is true in London with the

London Symphony. There is never this sort of question because when one

stands in front of the orchestra for the first three minutes the musicians

see the tenor but then no longer, because to move forward without a

professional musician [standing on the podium] would not be possible. The

preconception comes from the press, which does not understand and uses tenor

as a bad word. To say someone is a tenor is like saying that she is a woman

rather than a feminist, like referring to a stupid individual with no

rights. I

never impose it. I propose. Those who like the proposal accept it, those

who do not, don’t. I conduct a lot and in very important locales such as

the Vienna Opera and when you direct the Wiener, you conduct one of the

significant orchestras in the world, the same is true in London with the

London Symphony. There is never this sort of question because when one

stands in front of the orchestra for the first three minutes the musicians

see the tenor but then no longer, because to move forward without a

professional musician [standing on the podium] would not be possible. The

preconception comes from the press, which does not understand and uses tenor

as a bad word. To say someone is a tenor is like saying that she is a woman

rather than a feminist, like referring to a stupid individual with no

rights.

The buzz surrounding the concert was the announcement

of the ‘music’ of José Cura.

Because of it, the highest points in the entire

night were the sonnets, twenty minutes of music of very strong intensity and

that says a lot. When you write something people have not felt, makes no

sense to them, they start fidgeting and begin coughing. Therefore, it was

very emotional, and one must not forget this was a premier, that while the

audience was listening, and it is complicated [music], they were already

analyzing it and enjoying it. There was a lot of work (in composing), hard

work with theatrical awareness. Every harmony and every melodic turn tried

to continue the poetry of Neruda.

In our city, there is a lot of music and many musicians

who feel dissatisfied with what they can and cannot do.

There is something everyone needs to know: nobody

comes to seek you out, and this is true not only in Rosario or in

Argentina: it is that way in the world. Youth has a tendency to say ‘I am

the best in the world but no one knows it.’ I know many cases like that,

both colleagues and students, who come to me and say ‘Maestro, what do I

have to do?’ and I tell them they must go out and bang on doors, and they

say to me ‘But what happened that made you so lucky?' Luck? I have spent

more than thirty years doing this and only in the last ten or fifteen years

have I begun to see the fruit. Recently, in the last five years of my life,

I have been transformed by an event that is very easy to obtain—the event of

maturing.

Sometimes, someone will ask me how it feels to be

famous and I say nothing at all, because it is so easy to become famous.

Nowadays, with the mass media, being a celebrity is almost free. The

difference is to achieve the sort of fame that is transformed into greatness.

Sometimes the decision to leave or to stay can be very

difficult.

Emigration is always difficult. Even though now it

is easier for us than for our grandparents, that does not stop it from being

traumatic. When you move to a country where nobody greets you, nobody knows

you, and when you present your work visa they look at you badly simply

because you are Argentine or because you are a foreigner, and there is

nothing you do to avoid it, and that it what happened to my wife and me.

There were many people who told me not to leave but if I had a contract I

would not have gone. For example, in Buenos Aires some singers asked me how

they were singing and I said good. “Well, then, if you have a contract you

can send it to me.” No, it doesn’t work like that.

The concert ended with “Aurora” by Hector Panizza, the

same aria that was sung together with the audience at the Monument to the

Flag, the same one which he also occasionally surprises the English

audiences. Despite the respiratory problem that appeared in the last note

of the aria, when the audience asked one more from him, Cura , with

humility, agreed to one last one.

You have a work dedicated to the Malvinas. What has

happened to it has not be produce?

I knocked on two or three doors and they were not

opened, nobody seemed interested in it. Perhaps it was not the moment.

When I wrote it in 1984, I was 22 years old and we were entering a

democracy. It is a work for two choirs, with the dream being there would be

an Argentine choir and an English choir, quartet soloist, a children’s

choir, an orchestra—a very big, very expensive work. I wrote it in ’84 and

there it remains, and if some day I decide to do it perhaps I will have to

revise it, because many years have passed and with them a lot of experience

has been gained, or maybe not, because perhaps it would be nice to show what

a boy of 21 wrote at that age.

José Cura

ParaTi

19 July 2007

Julieta Mortati

The renown Argentine tenor, currently living in Madrid,

is in Buenos Aires for the opera Samson et Dalila in the Teatro Coliseo. In

a chat with Para Ti, he related how he studied music, martial arts, and even

gave classes in body building to survive. He began to sing at the age of 27

because “I discovered that my voice could pay my bills.” He is considered to

have one of the best voices in the world for its interpretative quality.

.jpg) José

Cura (44) traveled to Argentina to attend the golden anniversary of his

parents (the celebration is on Saturday 7 July in Rosario, his hometown).

He is accompanied by his wife, Silvia, and their three children: José (19),

Yazmín (14) and Nicolás (11). The visit, at first a secret, was quickly

divulged and the family plan was subsequently interrupted by five

performances of Samson et Dalila (by Camille Saint-Saëns) in the Teatro

Coliseo, with the artistic support of the Teatro Colón, and in Rosario with

the festival of the 50 years of the Monument to the Flag and a chamber

concert in commemoration of the 25th anniversary of Mozarteum,

(8 July) where he will present the world premier of the

Sonetos cycle, seven pieces composed

for the poetry of Pablo Neruda. In his last week in this country, he walks

with bags under his eyes and runny nose. “On the stage it is cold,” says

Cura of the Teatro Coliseo, “And it was not only cold but windy! Yesterday

it was blowing off my shirt and the boys in the chorus were wearing cravats

and scarves on stage. We endured, “but in the end the body just says

‘enough!’. José

Cura (44) traveled to Argentina to attend the golden anniversary of his

parents (the celebration is on Saturday 7 July in Rosario, his hometown).

He is accompanied by his wife, Silvia, and their three children: José (19),

Yazmín (14) and Nicolás (11). The visit, at first a secret, was quickly

divulged and the family plan was subsequently interrupted by five

performances of Samson et Dalila (by Camille Saint-Saëns) in the Teatro

Coliseo, with the artistic support of the Teatro Colón, and in Rosario with

the festival of the 50 years of the Monument to the Flag and a chamber

concert in commemoration of the 25th anniversary of Mozarteum,

(8 July) where he will present the world premier of the

Sonetos cycle, seven pieces composed

for the poetry of Pablo Neruda. In his last week in this country, he walks

with bags under his eyes and runny nose. “On the stage it is cold,” says

Cura of the Teatro Coliseo, “And it was not only cold but windy! Yesterday

it was blowing off my shirt and the boys in the chorus were wearing cravats

and scarves on stage. We endured, “but in the end the body just says

‘enough!’.

What does it mean for you to sing in Buenos Aires?

Well, it is not the same thing to sing for your people

and your family as it is to sing for those who have your respect because

they are your fans but who do not know you, do not know the man on the other

side. When you sing in your country, you know that in the audience are

people who knew you as a boy.

In his childhood, Cura learned to play the piano by

intuition, watching as his father interpreted Beethoven and Chopin. Later

he studied guitar, composition and piano, and entered the School of Art at

the University of Rosario. By 12 he had already begun to direct choirs and

orchestras. Along the way, he specialized in martial arts and played

rugby. Then at 27 he began to sing. “Singing appears rather late in my

musical career. I discovered that I had a voice and initially the

investment seemed very logical: with this voice I was going to be able to

eat and to give food more easily to my family than with composing. As crude

as that sounds, I started singing for purely economic reasons,” he admits

and then explains: “That which began as a blind date ended in a life-long

relationship but in the beginning I believed I was going to sing for only a

few years to relieve the situation, to pay the bills and pay for my house.

Finally, it turned into the full-time profession that transformed me into

what I am. There is a thing called destiny…I cannot complain.”

And when things went badly for him, he didn’t complain,

either. In 1983 he wanted to enter the Teatro Colón but a teacher at the

audition told him, “You do not sing, you shout.” The he gave classes in tae

kwon do, body building, and worked in a hardware store. In 1990 he took a

second audition at the Colón and finally they accepted him, but he decided

to leave for Europe. With his wife—whom he met at 16—and José, his first

son, Cura took a Pan Am flight toward Milan.

[NB:

As most of his fans are aware, Mr. Cura was accepted at the Colón in

1983 and rejected in 1990, after which he decided to move to Europe.

The reporter just got the dates mixed up but we wanted to let you know

the real story.]

A Stubborn Man

.jpg) -

I was always very stubborn. Like young children, each time they get up in

the morning it is not important to them what happened the previous day, just

that they are going to play again. I believe I am like that. I was always

convinced I had something to say, I was prepared to say it, and was going to

keep on saying it until I finally found someone who would listen to what I

had to say and then this person would pass it on to others. It is being

eternally young beyond all mistakes and objections. It causes one to want

to continue forward with the same thing. -

I was always very stubborn. Like young children, each time they get up in

the morning it is not important to them what happened the previous day, just

that they are going to play again. I believe I am like that. I was always

convinced I had something to say, I was prepared to say it, and was going to

keep on saying it until I finally found someone who would listen to what I

had to say and then this person would pass it on to others. It is being

eternally young beyond all mistakes and objections. It causes one to want

to continue forward with the same thing.

In 1995 [editor's note: he won in 1994], Cura

won the Operalia singing contest, presided over by Plácido Domingo, and

quickly became one of the most prestigious tenors in the world, especially

praised for his interpretive qualities. A year later, he made his début in

the role of Samson at the Royal Opera House in London, a role that he

continues to perform and for which he received the Orphée d’Or and

Echo Klassik awards.

- What is important for you to interpreting Samson et

Dalila?

- One of the things in regards to this opera is its use

of force. Some fifteen hundred years before Christ there was killing in the

name of God, and 3500 years later, it is the same thing. Humans still do

not have the courage to take responsibilities for their mistakes or their

successes. If we need to kill, the fault is with the other, and if we use

God, so much the better because no one can complain or say anything.

- And personally?

- This opera has a special aura because it has been

with me practically throughout my career. I have it very well done, very

well chewed, very studied, and very sung. The character is the same in all

works, the equation is different. Every performance is like an act of love,

a sexual act, and it is the audience who is your partner at this moment.

And you have to ask yourself, “How much do I give to the artist?” The

difference between an audience who succumbs to the artist and one that does

not is enormous. It is like making love to a plastic doll.

- How do you prepare for your roles?

- The voice functions like the face of a model. When

you are going to do a photography shoot, you have to treat yourself to more

sleep so that you have the least ‘wrinkles’ possible. And on the day of a

performance, if a singer tries to rest everything so the voice can be as

fresh as possible, that is ideal.

- Why did you decide to live in Europe?

- I like Madrid, we have a most beautiful house where I

am able to have all the things I want in my life, achieve all my whims.

- Do you have the tastes of a divo, eccentricities?

- Eccentricities, none. But, yes, I give myself the

things that I want. I have a wine cellar in my home, with a pile of wine I

have collected. I have a pool, a gymnasium, the things that we have always

wanted in the way we like most.

Cura confesses that when he is alone in the house he

enjoys silence and he never sings in the shower. He prefers to shop, to

cook, and to taste wine.

- And you also like photography?

- Yes, I love it, and we are now negotiating the

release of my first book of photographs with a Swiss publisher. I like

news-photography, not posed photos, and take to the streets with my camera

to collect the testimony of the entire world. I grab hold of my camera and

get lost. I have ended up in some screwed up neighborhoods and more than

once have had to be removed from complicated situations. I love to know the

true face of a town.

- Opera is often considered to be of the elite. Is

this something that bothers you?

- It is always spoken of as elite, but anywhere in the

world the ticket price to listen to an opera costs less that the cost of

tickets to the [sports] field. For many years there was a tendency: people

who liked classical music wanted to feel exclusive, but that is stupid

because the composers wrote the music for everyone. They were simple

people, but not easy people. They were geniuses because they were simple,

and this trend to deify them became fashionable at the beginning of the

twentieth century, when these divisions were created for the purpose for

with which all divisions are created: “Divide and you will rule.’ When in

fact there is only good music and bad music. There is boring classical

music and brilliant popular music.

José Cura: Titan of the

Opera

He has just arrived in the

country to dazzle us with his talent. This Argentine tenor, who has

already triumphed in Europe, will sing today in Rosario.

[gist translation]

José

Cura is one of the tenors in greatest demand on the international stage and

also one of the most popular figures in classical music, but he does not

agree with such high praise. His is a multifaceted talent (singer,

conductor, composer, guitarist, régisseur and businessman), impelled by a

spirit always eager for creativity and challenges, leading him on a journey

toward artistic satisfaction. Always on the edge of frenzy from this

fascinating life, Cura’s temperament seems to have been forged to enjoy

facing risks, as a real titan, and not in vain has it been written that his

is one of the greatest voices of the century. For all that, and in spite of

his youth, José Cura has already joined Olympus as one of the mythical

singers [sacred monsters] of the 21st century. José

Cura is one of the tenors in greatest demand on the international stage and

also one of the most popular figures in classical music, but he does not

agree with such high praise. His is a multifaceted talent (singer,

conductor, composer, guitarist, régisseur and businessman), impelled by a

spirit always eager for creativity and challenges, leading him on a journey

toward artistic satisfaction. Always on the edge of frenzy from this

fascinating life, Cura’s temperament seems to have been forged to enjoy

facing risks, as a real titan, and not in vain has it been written that his

is one of the greatest voices of the century. For all that, and in spite of

his youth, José Cura has already joined Olympus as one of the mythical

singers [sacred monsters] of the 21st century.

An anticipated return home

He returned to Argentina, like one of our more prodigal

sons, for a concert production of the opera Samson et Dalila by

Teatro Colon, but most of all to his audience, to their affection, and to

his family. “After 16 years in Europe, my house, in a physical sense, is no

longer in Argentina. But my feelings, my memories and my most intimate

experiences, these will always continue to remain in my country. I am happy

to return and meet again with the people with whom I grew up in an artistic

sense. I want to see the countrymen with whom I was lucky enough to share

the ‘kindergarten’ of the stage,” recounted José in a talk in Berlin,

Germany, not long before he returned home. And then, as it could not

otherwise be, speaking of reunions inevitably means speaking of memories and

the conversation, with Cura showing a less familiar side, could not help but

begin with his beloved hometown, Rosario.

Memories of Rosario

“The

oldest images I retain of Rosario,” he recalls, “are the first two or three

days of primary school. I do not know if that was in the LaSalle or San

José School, because after three days my parents withdrew me to enroll me

into a new school, one that had just opened by the brothers of Saint Patrick

of Ireland. We were the first class. There were barely two rooms and a

patio. My class was also the first class to graduate. Today it is a great

school, one of the biggest in Rosario. The last time I was in Argentina, in

1999, I visited the school, I met with the students and I encountered a

couple of my former companions. So there is where I begin my memories of

Rosario, in the little school of St Patrick. In reality so many years have

passed…and it is only now when I return that I perceive this passing of

time.” The imaginary route soon pass by his old house near the river and

the second one in the first residential district of Rosario. Almost

immediately, and understanding the strong connection that joins them, music

arrived and, of course, with it the beginning of the history whose future

chapters would cause him to do nothing less than conquer the world. “Music

always formed part of my family. My father played piano well enough. I

have a very clear image of when, as a boy, I watched him, seated at the

piano, playing Chopin and Liszt. Then he tried to imprint on me his own

story as a boy, sending me to study piano with a teacher in the

neighborhood. But the initiative did not work.” After a few months, the

teacher dismissed his young student with a brief note sent to his parents,

in which he explained, sadly, that it would be best to wait for a time when

an interest [in music] developed in José that had, to that moment, not been

demonstrated, and at the same time he recommended looking for a hobby that

appealed to the young man, because musical sensitivity did not seem strong

in him. “It was probably true at that time, and the best example was that,

from that moment, I began to devote myself to rugby.” “The

oldest images I retain of Rosario,” he recalls, “are the first two or three

days of primary school. I do not know if that was in the LaSalle or San

José School, because after three days my parents withdrew me to enroll me

into a new school, one that had just opened by the brothers of Saint Patrick

of Ireland. We were the first class. There were barely two rooms and a

patio. My class was also the first class to graduate. Today it is a great

school, one of the biggest in Rosario. The last time I was in Argentina, in

1999, I visited the school, I met with the students and I encountered a

couple of my former companions. So there is where I begin my memories of

Rosario, in the little school of St Patrick. In reality so many years have

passed…and it is only now when I return that I perceive this passing of

time.” The imaginary route soon pass by his old house near the river and

the second one in the first residential district of Rosario. Almost

immediately, and understanding the strong connection that joins them, music

arrived and, of course, with it the beginning of the history whose future

chapters would cause him to do nothing less than conquer the world. “Music

always formed part of my family. My father played piano well enough. I

have a very clear image of when, as a boy, I watched him, seated at the

piano, playing Chopin and Liszt. Then he tried to imprint on me his own

story as a boy, sending me to study piano with a teacher in the

neighborhood. But the initiative did not work.” After a few months, the

teacher dismissed his young student with a brief note sent to his parents,

in which he explained, sadly, that it would be best to wait for a time when

an interest [in music] developed in José that had, to that moment, not been

demonstrated, and at the same time he recommended looking for a hobby that

appealed to the young man, because musical sensitivity did not seem strong

in him. “It was probably true at that time, and the best example was that,

from that moment, I began to devote myself to rugby.”

Musical Beginnings

But

when did he discover his extraordinary vocation in music and what was that

cause that permanently awoke his sensibilities? Oddly and without warning,

that event was the result of an examination to enter secondary school. “I

was there with one of my best friends. He played his guitar, the Beatles

were fashionable, and he created a lot of interest. I learned to play

immediately and the experience awoke the calling that had been sleeping

within me.” This was the friend who gave him his first set of tools. Soon,

his father contacted Ernesto Bitteti (an old family friend), and Bitteti

recommended a professor with whom to study seriously. That began the

history with the guitar. “With my exuberant and extroverted personality, I

was like a time bomb. I learned to play well enough, although always

somewhat hampered by my very large hands…the things were causing me quite a

lot of work but I managed to have good results. The guitar, though, very

quickly made me feel small, not in a technical sense but in the fact of it

being a very introverted instrument. For that reason, I entered the

Conservatory in Rosario to study conducting and composition.” But

when did he discover his extraordinary vocation in music and what was that

cause that permanently awoke his sensibilities? Oddly and without warning,

that event was the result of an examination to enter secondary school. “I

was there with one of my best friends. He played his guitar, the Beatles

were fashionable, and he created a lot of interest. I learned to play

immediately and the experience awoke the calling that had been sleeping

within me.” This was the friend who gave him his first set of tools. Soon,

his father contacted Ernesto Bitteti (an old family friend), and Bitteti

recommended a professor with whom to study seriously. That began the

history with the guitar. “With my exuberant and extroverted personality, I

was like a time bomb. I learned to play well enough, although always

somewhat hampered by my very large hands…the things were causing me quite a

lot of work but I managed to have good results. The guitar, though, very

quickly made me feel small, not in a technical sense but in the fact of it

being a very introverted instrument. For that reason, I entered the

Conservatory in Rosario to study conducting and composition.”

One of his teachers—who at the time was the director of

the conservatory—gave him the advice that changed his life forever: “His

comment determined who I am today. He said to me: To become a better

conductor and composer, you will have to study singing.’ Indeed, following

his advice I began singing opera and ended up becoming a singer.”

Everything that happened after that is more or less well-known history; in

1983 he auditioned for the Teatro Colon, in 1991 he left for Europe, where

success and fame waited for him with open arms and rewarded him for years of

sacrifice in pursuit of his dream.

Today, and for some time, José Cura has been one of the

biggest names on the international music scene. He is an exceptional

professional who believes art is a profound path in life.

“One

of the characteristics of classical music is that it is one of the few forms

of art that remains, between one person and another, a single thing: to the

work of art itself. We interpret that work live, without networks and

without lies. That artisan concept is probably the most important aspect of

music and, in my opinion, why it continues to work, although as a spectacle

it may be a little anachronistic. It is an art of skin and bone, fact with

flood, sweat and tears, and for that reason it is an expression that stays

alive. It is my hope that all people, at least once in their lives, are

touched by this sensation, so powerful and so extraordinary.” “One

of the characteristics of classical music is that it is one of the few forms

of art that remains, between one person and another, a single thing: to the

work of art itself. We interpret that work live, without networks and

without lies. That artisan concept is probably the most important aspect of

music and, in my opinion, why it continues to work, although as a spectacle

it may be a little anachronistic. It is an art of skin and bone, fact with

flood, sweat and tears, and for that reason it is an expression that stays

alive. It is my hope that all people, at least once in their lives, are

touched by this sensation, so powerful and so extraordinary.”

Love of Cerulean Blue and White

In one of his latest disks, called Aurora, José Cura

included a special dedication to ‘his country’ and printed the Argentine

flag on the cover. After launch ofthat record (2002) Cura said, “I want my

people to know that, for the entire world and with much pride, José Cura is

an Argentine tenor.”

Two Rosario

Musicians

Marcelo Menichetti

Tenor José

Cura and pianist Eduardo Delgado will offer a concert today at 2100, at

Auditorio Fundación Astengo, Mitre 754. The Rosarinos artists will be

commemorating the 25th anniversary of the Mozarteum Argentino

Filial Rosario.

On

this occasion they will present a program that includes the spiritual “Were

You There”, “Cantata” by John Carter, “For a dead infant” as a piano solo,

“Soneto IV” by Carlo Guastavino and the works of Gabriel Fauré “Prison” and

“Chason dámour”. After ‘Balada en sol menor Op. 23” by Maurice Ravel for

solo piano, “Sonetos”, seven musical works composed by José Cura based on

the poems of Pablo Neruda, will be presented. On

this occasion they will present a program that includes the spiritual “Were

You There”, “Cantata” by John Carter, “For a dead infant” as a piano solo,

“Soneto IV” by Carlo Guastavino and the works of Gabriel Fauré “Prison” and

“Chason dámour”. After ‘Balada en sol menor Op. 23” by Maurice Ravel for

solo piano, “Sonetos”, seven musical works composed by José Cura based on

the poems of Pablo Neruda, will be presented.

In the second

part of the concert the artists will perform “Nocturno” by Alberto Muzzio

and “Canción del árbol del olvido” by Alberto Ginastera, with more

selections from the works of Carlos Guastavino including “Se equivocó la

paloma”, “La rosa y el sauce”, “Campanilla”, “Canción de perico”, “El único

camino”, Elegía para un gorrión” and “Canción del carretero”. Finally there

will be the “Canción a la bandera” by Héctor Panizza and, for solo piano,

“Sonatina” by Carlos Guastavino and “Adiós Nonino” by Astor Piazzolla.

During

rehearsal prior to the presentation, the artists talked with La Capital

about their pleasure at the opportunity to celebrate the anniversary of the

Mozarteum Argentino Filial Rosario and at the same time to perform together

in front of their hometown. “This recital is the first time we have worked

together,” declared Delgado. “Before this, we did the CD Anhelo (1999), in

which the guitarist Ernesto Bitetti also participated,” he explained.

Cura performed a series of

“Samsons” in concert version at the Teatro Coliseo in Buenos Aires that

received very good reviews. “There is great payback in the spectacle and

more than anything else the emotions of singing with all my companions from

the Colón after an absence of eight years,” explains the singer, “created an

emotional charge of such great energy that it shocked the audience.”

Delgado is happy to share the celebration: "I feel

very honored to do this with José, because he is an international figure who

performs in all the great theaters in the world and the chosen schedule is

of our music, which is so beautiful,” he said.

The pianist, who has recorded all the work of Alberto

Ginastera and is now preparing for a concert he will give in London next

November, emphasized that next to Cura, the star of the performance will be

"a concert of chamber music, not of song and piano. The piano and the voice

become two instruments in dialogue and with José I have a very special

musical understanding".

Both musicians reveal a state of mind with a degree of

anxiety they do not try to hide. “We artists are like football players

because when we enter the field, it doesn’t matter to the people that we

have played well and scored ten goals before: it is what you do for them

now,” Cura explains.

José Cura

Writes of Love

The tenor premieres his own

songs based on poems of Pablo Neruda

Saturday

July 7, 2007

With

his performances in Samson et Dalila presented by the Teatro Colón,

José Cura gave ample evidence to the Argentine public of why his name is

where it is in the world of opera. Nevertheless, and not to lose the habit

of being pleasantly surprised, an important moment still remains on his

agenda before the tenor returns to Europe. It is a question this time of

the world premiere of his Sonnets, based on the poems of Pablo

Neruda, that take place tomorrow in the program for the Mozarteum of

Rosario, which is celebrating its Silver Anniversary with a concert by José

Cura and pianist Eduardo Delgado in the Foundation Astengo. The two,

acquainted through the CD of Argentine music Anhelo, will offer a

chamber recital, including songs from the recording, works for solo piano,

and the pieces composed by Cura. With

his performances in Samson et Dalila presented by the Teatro Colón,

José Cura gave ample evidence to the Argentine public of why his name is

where it is in the world of opera. Nevertheless, and not to lose the habit

of being pleasantly surprised, an important moment still remains on his

agenda before the tenor returns to Europe. It is a question this time of

the world premiere of his Sonnets, based on the poems of Pablo

Neruda, that take place tomorrow in the program for the Mozarteum of

Rosario, which is celebrating its Silver Anniversary with a concert by José

Cura and pianist Eduardo Delgado in the Foundation Astengo. The two,

acquainted through the CD of Argentine music Anhelo, will offer a

chamber recital, including songs from the recording, works for solo piano,

and the pieces composed by Cura.

The history of these Sonnets was born

in 1995, when José sang in Palermo (Sicily) in the Zandonai opera

Francesca di Rimini, based on the legendary lover Romeo and Juliet.

Someone—he never knew who—left a book of Neruda poems in his dressing room

with an anonymous dedication that says, “For you, who sing of love, words of

love.” On opening the book, according to the tenor, the first thing he

read was the last sonnet that says “When I die, I want you hands on my eyes”

and he was so moved by emotion that the music was composed almost at once in

a single moment of inspiration. He continued with “My love, if I should die

and you should not” until the commitments and the dizzying life of the

singer on the rise forced him to put all the beautiful ideas and sensation

in a drawer not to be opened for several years, until, in 2006, the composer

firmly decided to finish the project and to choose the sonnets that, he

felt, still remained to complete the cycle. The author of the dedication,

very romantically, has never been revealed.

In Buenos Aires, La Nacion met with Cura and

Delgado. The pianist referred to the work as personal music whose harmonies

declare a proper and elaborate language. “They do not look like anything

else. They are interesting works and with their polyphonies and

counterpoints, they are also difficult. It gave me pleasure to work with

them because they demanded I study them and because I feel I can relate with

José’s musicality,” Delgado explained.

In turn, Cura added comments that referred

to the composition of the Sonnets.

-Are they composed for your own voice?

They are written for a high baritone because I consider

the voice of a baritone the most beautiful one for chamber music, as in that

of the mezzo for a woman. The middle zone is where the voice flows more

sweet and less forced. This reflects my own vocals: a dark voice with the

ability to sing high notes. It is not possible to sing them like normal

songs. They are intellectual, which means they cannot be learned by hearing

them, it is necessary to be able to read and to understand in depth the

music that, in reality, is a long duet of piano and song.

- How did you transfer the musicality of the

word to that of the singing voice?

-The poetry of Neruda awaken the senses, is

theatrical in an old-fashioned way. Each word is loaded with theater and

drama. The options were to write melody accompany the words or to write

music, but with the sensory wealth that opens us up to Neruda’s fascinating

world. The complexity of the music is related to that of the text, so that

it is not necessary to listen to distill pure melody. One must concentrate

in the poems, leaving the melody to present itself alone.

Song and Piano Combine for an

All-round Tribute

José Cura and Eduardo Delgado

celebrated 25 years of the Mozarteum Rosario.

Marcelo Menichetti

The Rosario affiliate of the

Argentinean Mozarteum celebrated 25 years of operation in the city with an

outstanding concert starring tenor José Cura and pianist Eduardo Delgado.

The Rosarino artists, who now live abroad, returned to their hometown to

offer a repertoire of songs which reached absolute high points in the world

premiere of the “Sonetos”, poems by Pablo Neruda set to music by José Cura,

in the instrumental versions by Delgado of Astor Piazzolla’s “Adiós Nonino”

and Carlos Gustavino’s “Bailecito”, and in the brilliant closure with the

“Cancion a la bandera” from Hector Panizza’s opera “Aurora”.

The Fundación Astengo Auditorium was

filled to capacity on the cold night that was last Sunday. The

not-be-postponed, not-to-be-missed event brought the highly acclaimed

singer, who provided the city and his pianist with major international

exposure, back on stage. The reason for the convocation was no less

important: the 25th anniversary of an institution that made

possible the performance in Rosario of a large segment of the top exponents

of the classical genre in recent years, including musicians, conductors,

soloists, chamber ensembles and large orchestras as well as dancers and

singers.

With the check mark of audience

accord, the concert was characterized by a certain informality given it by

the two protagonists. Both artists, unquestionably affected by a cold,

paused to sip tea on stage. That gesture lent the necessary warmth to an

evening spent in a true atmosphere of celebration saluting years of labor

and fittingly capped by the presence of two sons of the city, who today are

winning applause around the world, and who returned to celebrate with music

an anniversary that even found a happy birthday (salute) offered from the

stage.

Translation:

Monica B.

Listen:

Chanson d'amour

La rosa y el sauce

Rosarino

Tenor José Cura

Rosario, 9 July 2007 (DYN) – The Rosarino tenor José

Cura performed in this city after an absence of eight years, accompanied on

piano by another internationally recognized son of Rosario, Eduardo Delgado,

in a celebratory recital in the Teatro Fundación Astengo.

The recital was carried out last night within the

framework of the 25th anniversary of the Mozarteum Argentino

Filial Rosario and before an enthusiastic and effusive audience that filled

the auditorium to capacity.

The audience was attentive to the singer in the

interpretation of works by John Carter, Carlos Guastavino, Alberto

Ginastera, Héctor Panizza, Leonard Bernstein, Gabriel Fauré and of Cura’s

own works, “Sonetos,” a series of songs inspired by the poetry of Chilean

Pablo Neruda.

Cura recalled that in 1999, while he was participating

in a production of Francesca di Rimini in Palermo, Italy, he returned

to his dressing room to find a book of poems by Neruda that had a totally

anonymous dedication: “For you, who sing of love, words of love.”

The tenor said that the emotions that filled him on

reading the verses immediately awoke the desire to compose songs for the

text, but he had to delay [completing the cycle] for some years until he

could finally finish in 2006.

Cura returned to his home town after a series of

concerts performances of Camille Saint-Saëns’ opera “Samson et Dalila” at

the Teatro Coliseo in Buenos Aires. The tenor was accompanied on this

occasion by Delgado, an outstanding pianist who has lived for three decades

in Los Angeles, in the United States, and who returns at least twice a year

to Rosario to visit his mother.

Delgado, who performs as well as teaches at important

educational institutions in the US, served last night as a first rate

accompanist and offered works by Maurice Ravel, Maurice Ravel, Carlos

Guastavino and Ástor Piazzola during the concert.

Cura emphasized that the poems of Neruda “Awaken the

senses, is theatrical in an old-fashioned way. Each word is loaded with

theater and drama.”

“They are written for a high baritone because I

consider the voice of a baritone the most beautiful for chamber music, just

as that of the mezzo is for a woman,” he said.

The tenor last performed in his hometown on Sunday, 11

April 1999, after an absence of twelve years, before an audience of some 40

thousand at the National Monument to the Flag in a concert that included

songs from the Beatles.

July 10, 2007

One of life’s mysterious gifts

José Cura studied composition at the

National University of Rosario’s School of Music, but his career channelled

him into song. “My composing goes back to that period in time; later on I

got totally wrapped up in singing, and today is today, “ recalled the artist

who today will premiere his musical adaptations of seven sonnets based on

the poetry of the Chilean Pablo Neruda. Pleased with (the fruits of) his

labor, he recalled the origin of the songs: “The beginning of this is very

strange and very sweet.” he says, folding his hands on the table before

continuing, “In 1995 I was singing in Palermo, Sicily, and at the end of one

of the performances, when I returned to my dressing room, I found a book of

poems by Neruda. I opened it, and inside was a dedication signed

“Anonymous”. I never knew who sent it to me: neither age, nor color, nor

gender. Nothing. What happened next was that I opened the book, stumbling

upon a poem that I really liked, and automatically set it to music the

following day.”

|

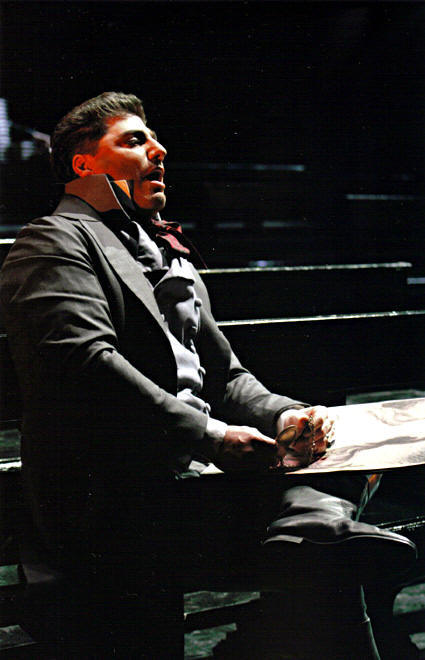

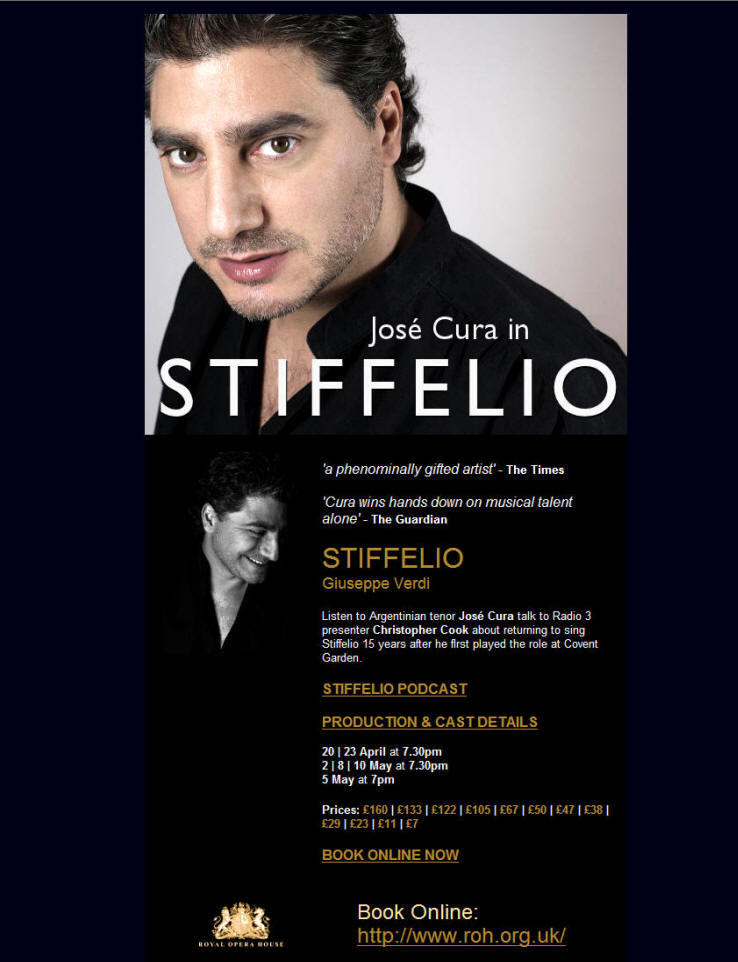

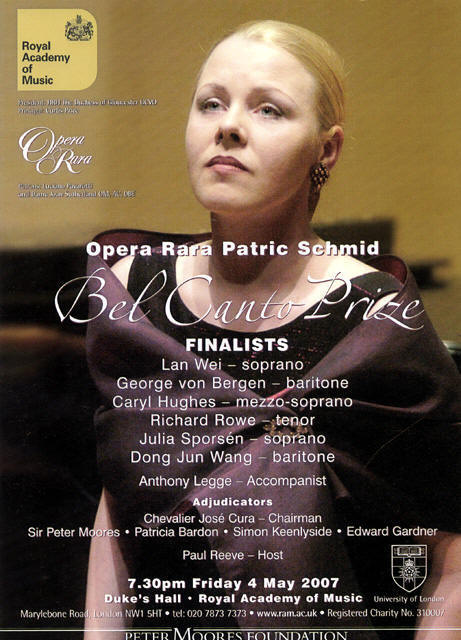

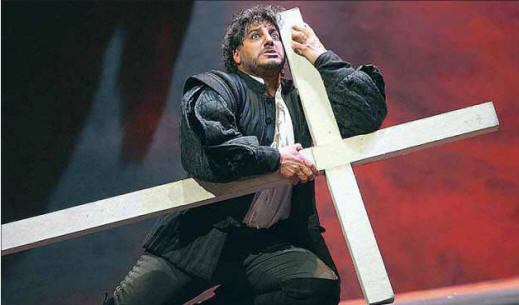

Almost exactly twelve years ago,

a young and largely unknown Argentinean tenor opened the Royal

Opera's Verdi Festival playing the title role in Stiffelio,

Verdi's long-neglected masterpiece of 1850. But in the interim,

José Cura has risen to become one of the most highly-acclaimed

and beloved singers of his generation; at Covent Garden, he has

performed leading roles in operas such as Samson et Dalila, Il

trovatore, Andrea Chénier and most recently La fanciulla del

West.

Almost exactly twelve years ago,

a young and largely unknown Argentinean tenor opened the Royal

Opera's Verdi Festival playing the title role in Stiffelio,

Verdi's long-neglected masterpiece of 1850. But in the interim,

José Cura has risen to become one of the most highly-acclaimed

and beloved singers of his generation; at Covent Garden, he has

performed leading roles in operas such as Samson et Dalila, Il

trovatore, Andrea Chénier and most recently La fanciulla del

West.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Regarding

the opera that he has come here to sing, “Stiffelio”—the same one in which

he made his London debut in 1995—Cura feels obliged to defend himself

against some of the reviews of the production that have recently been

published. The critics have made note of the extraordinary vocal power of

the principal singers, Cura (the Protestant pastor Stiffelio), the North

American soprano Sondra Radvanovsky (Lina, his adulterous wife) and the

Italian baritone Roberto Frontali (her father).

Regarding

the opera that he has come here to sing, “Stiffelio”—the same one in which

he made his London debut in 1995—Cura feels obliged to defend himself

against some of the reviews of the production that have recently been

published. The critics have made note of the extraordinary vocal power of

the principal singers, Cura (the Protestant pastor Stiffelio), the North

American soprano Sondra Radvanovsky (Lina, his adulterous wife) and the

Italian baritone Roberto Frontali (her father).

%20a.jpg)

%20a.jpg)

%20a.jpg)

%20a.jpg)

%20a.jpg)

%20a.jpg)

%20a.jpg)

.jpg)

%20a.jpg)

%20a.jpg)

World famous tenor José Cura has been in

Devon for a masterclass with 12 lucky opera singers culminating

in a gala concert at Stover School.

World famous tenor José Cura has been in

Devon for a masterclass with 12 lucky opera singers culminating

in a gala concert at Stover School.

.jpg)

Opera News, June 2007

//

R. Baxter

Opera News, June 2007

//

R. Baxter

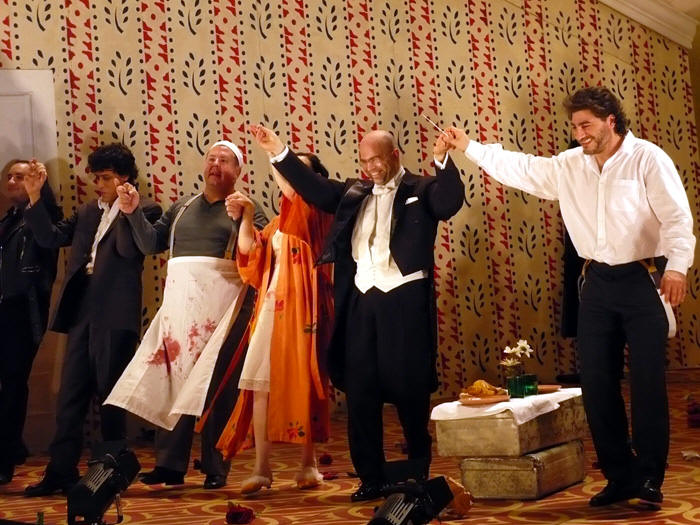

Applauded

by the critics for his interpretations of Giuseppe Verdi’s

“Otello” and Saint-Saens’ “Samson”, Cura is also recognized for

being the first artist to have sung and conducted the same work

simultaneously as well as being the first to combine vocal with

symphonic performances in the same concert.

Applauded

by the critics for his interpretations of Giuseppe Verdi’s

“Otello” and Saint-Saens’ “Samson”, Cura is also recognized for

being the first artist to have sung and conducted the same work

simultaneously as well as being the first to combine vocal with

symphonic performances in the same concert.

.jpg)

After

an eight year absence, the Rosarino tenor José Cura returns to

Buenos Aires in a concert version of Camille Saint-Saens’ opera

Samson and Dalila, which will be presented tomorrow at the

Coliseo as part of the Colón’s season. Recognized as one of the

great voices of today on the international scene, José Cura is a

very unusual artist who, besides singing, conducts orchestras,

composes, and also has recently started to make incursions into

stage management/directing.

After

an eight year absence, the Rosarino tenor José Cura returns to

Buenos Aires in a concert version of Camille Saint-Saens’ opera

Samson and Dalila, which will be presented tomorrow at the

Coliseo as part of the Colón’s season. Recognized as one of the

great voices of today on the international scene, José Cura is a

very unusual artist who, besides singing, conducts orchestras,

composes, and also has recently started to make incursions into

stage management/directing.

In

the fifteen years of his successful international career, José Cura has

frequented not only the most prestigious halls and theaters in the

classical music world (Met, Covent Garden, LaScala, Opera National in

Paris, Staatsoper in Vienna, Hamburg and Zurich, and the Deutsche Oper

in Berlin among others) but has also been present on remote stages, has

visited countries far removed from the traditional circuit, has

conquered exotic audiences as to opera and untiringly carried the art of

music and theater to inconceivable corners of the world. At his side

sing the most glamorous divas and direct the most celebrated conductors.

Parallel to his intense activity in the theater (as conductor, singer

and régisseur), he exploits his ample qualities as communicator and

showman with surprising ease, offering recitals and shows—some of them

on outdoor stages in front of thousands of people—in which he combines

singing with orchestral conducting (in an original format he himself

calls ‘half and half’), something that has earned him both the criticism

from the most conservative sectors of the music media and the admiration

of his fans, as well as an unusual popularity for an artist in the

classical genre.

In

the fifteen years of his successful international career, José Cura has

frequented not only the most prestigious halls and theaters in the

classical music world (Met, Covent Garden, LaScala, Opera National in

Paris, Staatsoper in Vienna, Hamburg and Zurich, and the Deutsche Oper

in Berlin among others) but has also been present on remote stages, has

visited countries far removed from the traditional circuit, has

conquered exotic audiences as to opera and untiringly carried the art of

music and theater to inconceivable corners of the world. At his side

sing the most glamorous divas and direct the most celebrated conductors.

Parallel to his intense activity in the theater (as conductor, singer

and régisseur), he exploits his ample qualities as communicator and

showman with surprising ease, offering recitals and shows—some of them

on outdoor stages in front of thousands of people—in which he combines

singing with orchestral conducting (in an original format he himself

calls ‘half and half’), something that has earned him both the criticism

from the most conservative sectors of the music media and the admiration

of his fans, as well as an unusual popularity for an artist in the

classical genre.

When

José Cura came down punctually to the lobby to give us his final interview

before returning to Europe, I thought it was gracious of him not to have

canceled after the effort of the previous night’s concert when he sang while

suffering from an untimely cold (for a singer, a cold is always untimely).

Besides, it was a very cold 9 July (Rosarinos hardly remember when it was

really cold) and many expected snow. I will never forget when it snowed

in Rosario a few days before my entire family was involved in a car accident

and we saw the snow on the windows of the hospital, recalled the

Rosarino musician (singer, director, composer) who now lives in Madrid but

works in capital cities around the world.

When

José Cura came down punctually to the lobby to give us his final interview

before returning to Europe, I thought it was gracious of him not to have

canceled after the effort of the previous night’s concert when he sang while

suffering from an untimely cold (for a singer, a cold is always untimely).

Besides, it was a very cold 9 July (Rosarinos hardly remember when it was

really cold) and many expected snow. I will never forget when it snowed

in Rosario a few days before my entire family was involved in a car accident

and we saw the snow on the windows of the hospital, recalled the

Rosarino musician (singer, director, composer) who now lives in Madrid but

works in capital cities around the world.

.jpg) José

Cura (44) traveled to Argentina to attend the golden anniversary of his

parents (the celebration is on Saturday 7 July in Rosario, his hometown).

He is accompanied by his wife, Silvia, and their three children: José (19),

Yazmín (14) and Nicolás (11). The visit, at first a secret, was quickly

divulged and the family plan was subsequently interrupted by five

performances of Samson et Dalila (by Camille Saint-Saëns) in the Teatro

Coliseo, with the artistic support of the Teatro Colón, and in Rosario with

the festival of the 50 years of the Monument to the Flag and a chamber

concert in commemoration of the 25th anniversary of Mozarteum,

(8 July) where he will present the world premier of the

José

Cura (44) traveled to Argentina to attend the golden anniversary of his

parents (the celebration is on Saturday 7 July in Rosario, his hometown).

He is accompanied by his wife, Silvia, and their three children: José (19),

Yazmín (14) and Nicolás (11). The visit, at first a secret, was quickly

divulged and the family plan was subsequently interrupted by five

performances of Samson et Dalila (by Camille Saint-Saëns) in the Teatro

Coliseo, with the artistic support of the Teatro Colón, and in Rosario with

the festival of the 50 years of the Monument to the Flag and a chamber

concert in commemoration of the 25th anniversary of Mozarteum,

(8 July) where he will present the world premier of the

.jpg) -

I was always very stubborn. Like young children, each time they get up in

the morning it is not important to them what happened the previous day, just

that they are going to play again. I believe I am like that. I was always

convinced I had something to say, I was prepared to say it, and was going to

keep on saying it until I finally found someone who would listen to what I

had to say and then this person would pass it on to others. It is being

eternally young beyond all mistakes and objections. It causes one to want

to continue forward with the same thing.

-

I was always very stubborn. Like young children, each time they get up in

the morning it is not important to them what happened the previous day, just

that they are going to play again. I believe I am like that. I was always

convinced I had something to say, I was prepared to say it, and was going to

keep on saying it until I finally found someone who would listen to what I

had to say and then this person would pass it on to others. It is being

eternally young beyond all mistakes and objections. It causes one to want

to continue forward with the same thing.

“The

oldest images I retain of Rosario,” he recalls, “are the first two or three

days of primary school. I do not know if that was in the LaSalle or San

José School, because after three days my parents withdrew me to enroll me

into a new school, one that had just opened by the brothers of Saint Patrick

of Ireland. We were the first class. There were barely two rooms and a

patio. My class was also the first class to graduate. Today it is a great

school, one of the biggest in Rosario. The last time I was in Argentina, in

1999, I visited the school, I met with the students and I encountered a

couple of my former companions. So there is where I begin my memories of

Rosario, in the little school of St Patrick. In reality so many years have

passed…and it is only now when I return that I perceive this passing of

time.” The imaginary route soon pass by his old house near the river and

the second one in the first residential district of Rosario. Almost

immediately, and understanding the strong connection that joins them, music

arrived and, of course, with it the beginning of the history whose future

chapters would cause him to do nothing less than conquer the world. “Music

always formed part of my family. My father played piano well enough. I

have a very clear image of when, as a boy, I watched him, seated at the

piano, playing Chopin and Liszt. Then he tried to imprint on me his own

story as a boy, sending me to study piano with a teacher in the

neighborhood. But the initiative did not work.” After a few months, the

teacher dismissed his young student with a brief note sent to his parents,

in which he explained, sadly, that it would be best to wait for a time when

an interest [in music] developed in José that had, to that moment, not been

demonstrated, and at the same time he recommended looking for a hobby that

appealed to the young man, because musical sensitivity did not seem strong

in him. “It was probably true at that time, and the best example was that,

from that moment, I began to devote myself to rugby.”

“The

oldest images I retain of Rosario,” he recalls, “are the first two or three

days of primary school. I do not know if that was in the LaSalle or San

José School, because after three days my parents withdrew me to enroll me

into a new school, one that had just opened by the brothers of Saint Patrick

of Ireland. We were the first class. There were barely two rooms and a

patio. My class was also the first class to graduate. Today it is a great

school, one of the biggest in Rosario. The last time I was in Argentina, in

1999, I visited the school, I met with the students and I encountered a

couple of my former companions. So there is where I begin my memories of

Rosario, in the little school of St Patrick. In reality so many years have

passed…and it is only now when I return that I perceive this passing of

time.” The imaginary route soon pass by his old house near the river and

the second one in the first residential district of Rosario. Almost

immediately, and understanding the strong connection that joins them, music

arrived and, of course, with it the beginning of the history whose future

chapters would cause him to do nothing less than conquer the world. “Music

always formed part of my family. My father played piano well enough. I

have a very clear image of when, as a boy, I watched him, seated at the

piano, playing Chopin and Liszt. Then he tried to imprint on me his own

story as a boy, sending me to study piano with a teacher in the

neighborhood. But the initiative did not work.” After a few months, the

teacher dismissed his young student with a brief note sent to his parents,

in which he explained, sadly, that it would be best to wait for a time when

an interest [in music] developed in José that had, to that moment, not been

demonstrated, and at the same time he recommended looking for a hobby that

appealed to the young man, because musical sensitivity did not seem strong

in him. “It was probably true at that time, and the best example was that,

from that moment, I began to devote myself to rugby.”  But

when did he discover his extraordinary vocation in music and what was that

cause that permanently awoke his sensibilities? Oddly and without warning,

that event was the result of an examination to enter secondary school. “I

was there with one of my best friends. He played his guitar, the Beatles

were fashionable, and he created a lot of interest. I learned to play

immediately and the experience awoke the calling that had been sleeping

within me.” This was the friend who gave him his first set of tools. Soon,

his father contacted Ernesto Bitteti (an old family friend), and Bitteti

recommended a professor with whom to study seriously. That began the

history with the guitar. “With my exuberant and extroverted personality, I

was like a time bomb. I learned to play well enough, although always

somewhat hampered by my very large hands…the things were causing me quite a

lot of work but I managed to have good results. The guitar, though, very

quickly made me feel small, not in a technical sense but in the fact of it

being a very introverted instrument. For that reason, I entered the

Conservatory in Rosario to study conducting and composition.”

But

when did he discover his extraordinary vocation in music and what was that

cause that permanently awoke his sensibilities? Oddly and without warning,

that event was the result of an examination to enter secondary school. “I

was there with one of my best friends. He played his guitar, the Beatles

were fashionable, and he created a lot of interest. I learned to play

immediately and the experience awoke the calling that had been sleeping

within me.” This was the friend who gave him his first set of tools. Soon,

his father contacted Ernesto Bitteti (an old family friend), and Bitteti

recommended a professor with whom to study seriously. That began the

history with the guitar. “With my exuberant and extroverted personality, I

was like a time bomb. I learned to play well enough, although always

somewhat hampered by my very large hands…the things were causing me quite a

lot of work but I managed to have good results. The guitar, though, very

quickly made me feel small, not in a technical sense but in the fact of it

being a very introverted instrument. For that reason, I entered the

Conservatory in Rosario to study conducting and composition.”  “One

of the characteristics of classical music is that it is one of the few forms

of art that remains, between one person and another, a single thing: to the

work of art itself. We interpret that work live, without networks and

without lies. That artisan concept is probably the most important aspect of

music and, in my opinion, why it continues to work, although as a spectacle

it may be a little anachronistic. It is an art of skin and bone, fact with

flood, sweat and tears, and for that reason it is an expression that stays

alive. It is my hope that all people, at least once in their lives, are

touched by this sensation, so powerful and so extraordinary.”

“One

of the characteristics of classical music is that it is one of the few forms

of art that remains, between one person and another, a single thing: to the

work of art itself. We interpret that work live, without networks and

without lies. That artisan concept is probably the most important aspect of

music and, in my opinion, why it continues to work, although as a spectacle

it may be a little anachronistic. It is an art of skin and bone, fact with

flood, sweat and tears, and for that reason it is an expression that stays

alive. It is my hope that all people, at least once in their lives, are

touched by this sensation, so powerful and so extraordinary.”

On

this occasion they will present a program that includes the spiritual “Were

You There”, “Cantata” by John Carter, “For a dead infant” as a piano solo,

“Soneto IV” by Carlo Guastavino and the works of Gabriel Fauré “Prison” and

“Chason dámour”. After ‘Balada en sol menor Op. 23” by Maurice Ravel for

solo piano, “Sonetos”, seven musical works composed by José Cura based on

the poems of Pablo Neruda, will be presented.

On

this occasion they will present a program that includes the spiritual “Were

You There”, “Cantata” by John Carter, “For a dead infant” as a piano solo,

“Soneto IV” by Carlo Guastavino and the works of Gabriel Fauré “Prison” and

“Chason dámour”. After ‘Balada en sol menor Op. 23” by Maurice Ravel for

solo piano, “Sonetos”, seven musical works composed by José Cura based on

the poems of Pablo Neruda, will be presented. With

his performances in Samson et Dalila presented by the Teatro Colón,

José Cura gave ample evidence to the Argentine public of why his name is

where it is in the world of opera. Nevertheless, and not to lose the habit

of being pleasantly surprised, an important moment still remains on his

agenda before the tenor returns to Europe. It is a question this time of

the world premiere of his Sonnets, based on the poems of Pablo

Neruda, that take place tomorrow in the program for the Mozarteum of

Rosario, which is celebrating its Silver Anniversary with a concert by José

Cura and pianist Eduardo Delgado in the Foundation Astengo. The two,

acquainted through the CD of Argentine music Anhelo, will offer a

chamber recital, including songs from the recording, works for solo piano,

and the pieces composed by Cura.

With

his performances in Samson et Dalila presented by the Teatro Colón,

José Cura gave ample evidence to the Argentine public of why his name is

where it is in the world of opera. Nevertheless, and not to lose the habit

of being pleasantly surprised, an important moment still remains on his

agenda before the tenor returns to Europe. It is a question this time of

the world premiere of his Sonnets, based on the poems of Pablo

Neruda, that take place tomorrow in the program for the Mozarteum of

Rosario, which is celebrating its Silver Anniversary with a concert by José

Cura and pianist Eduardo Delgado in the Foundation Astengo. The two,

acquainted through the CD of Argentine music Anhelo, will offer a