|

|

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. José Cura uses language with precision and purpose; the computer does not. We offer it only a a general guide to the conversation and the ideas exchanged but the following should not be considered definitive.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Build Starts

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

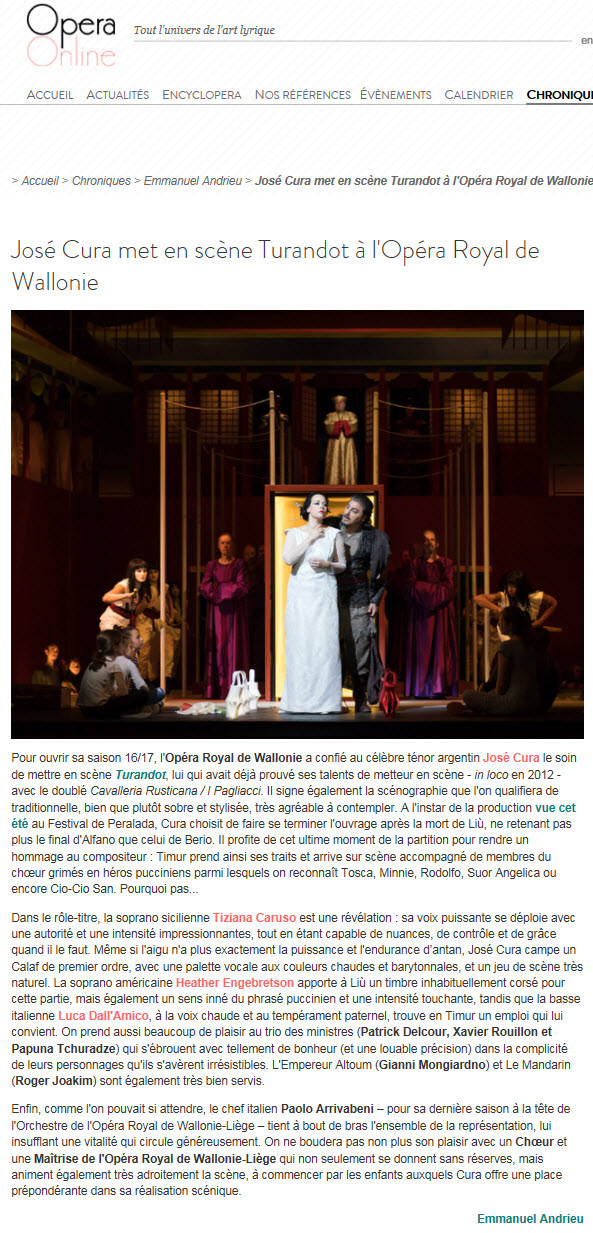

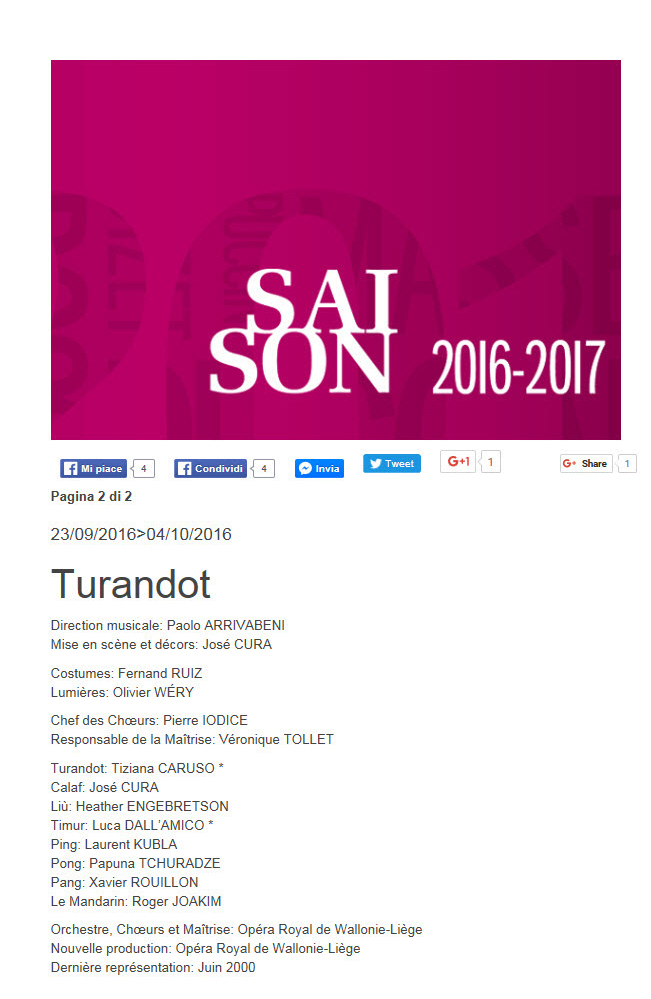

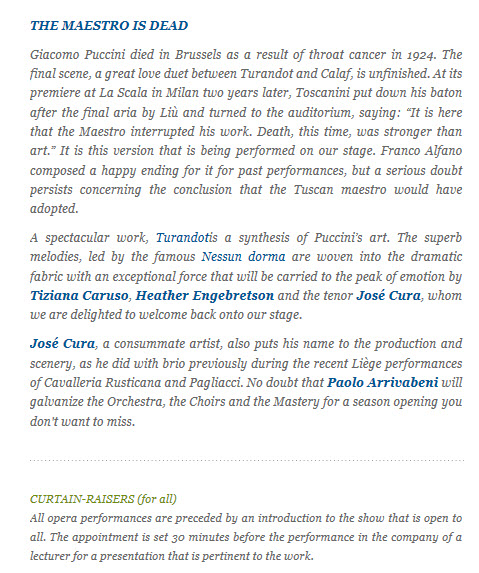

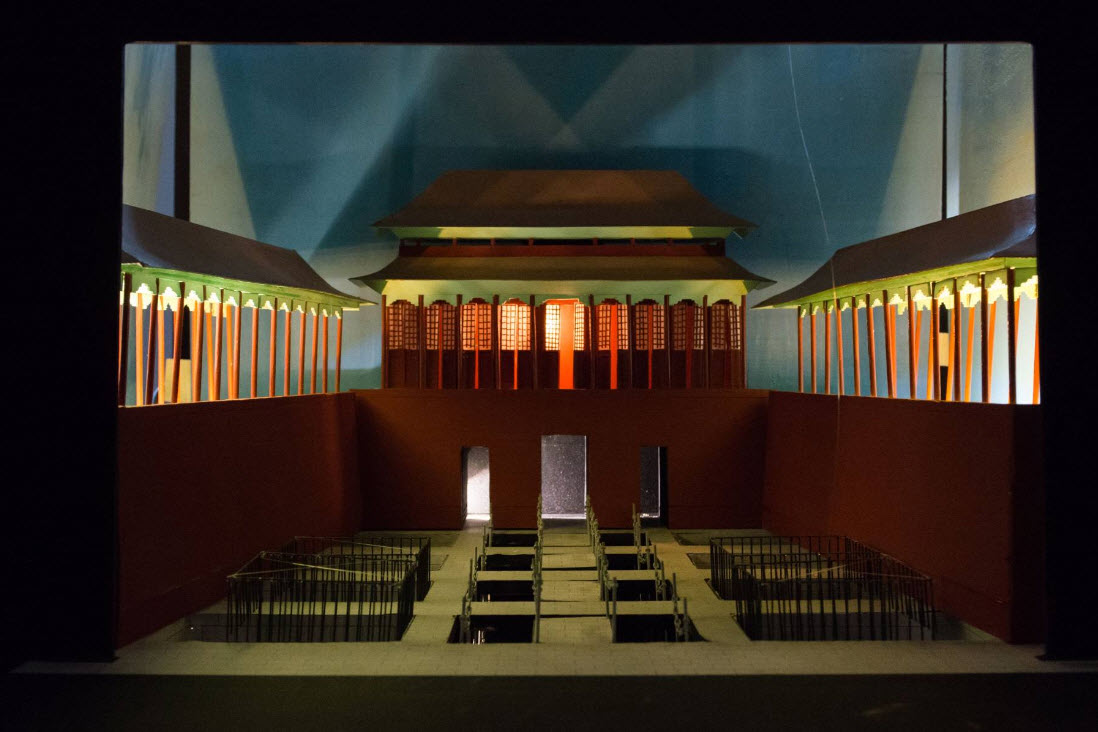

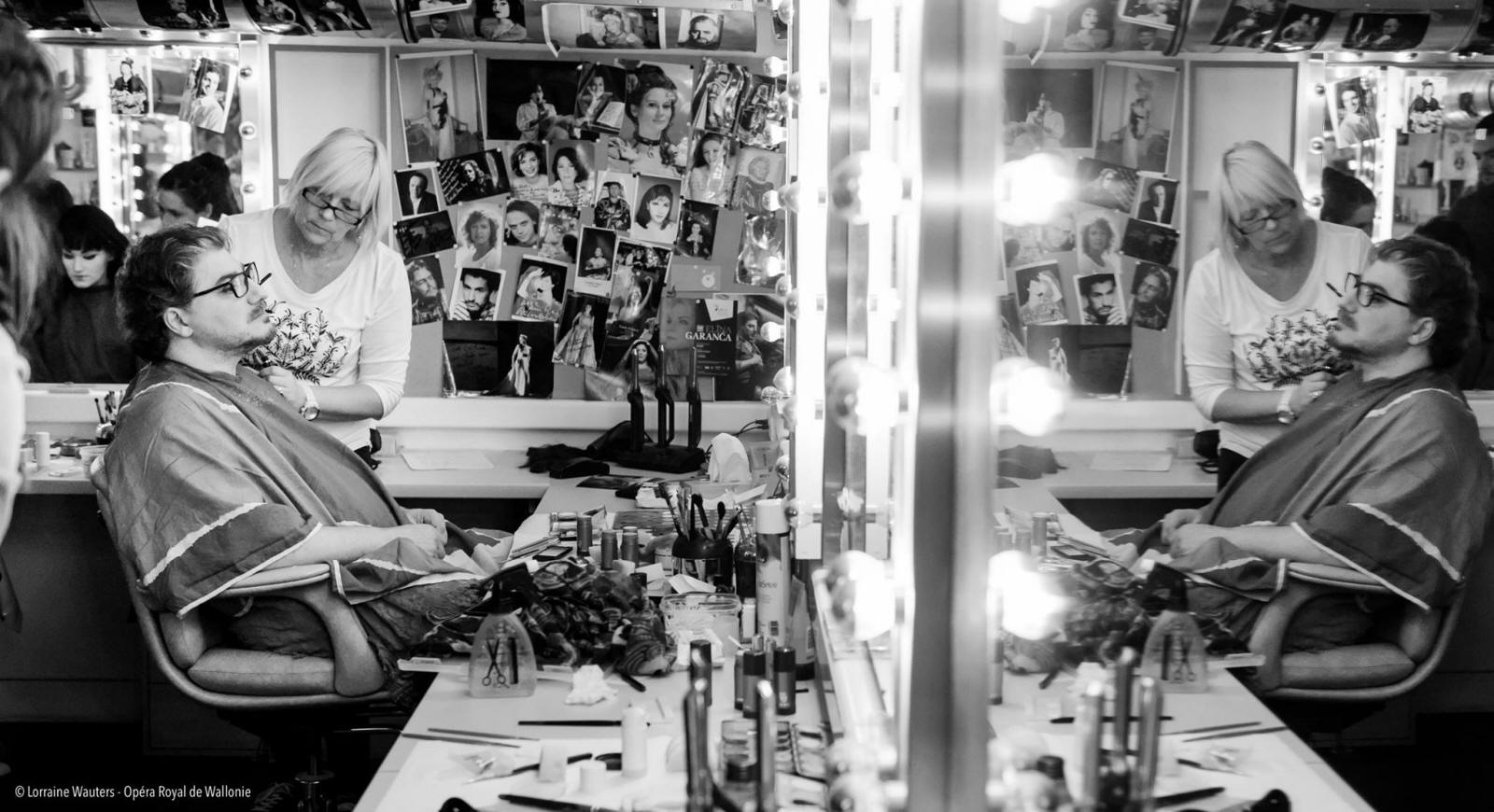

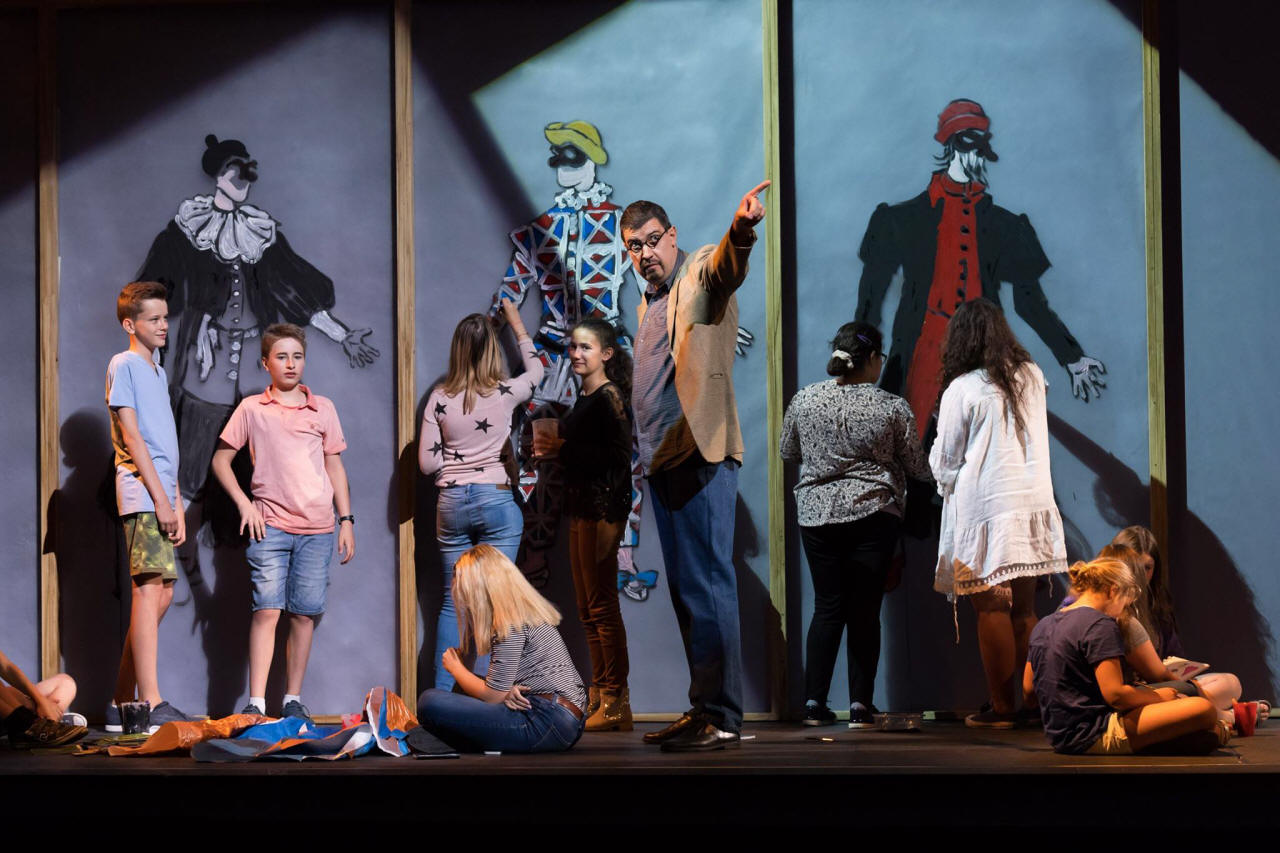

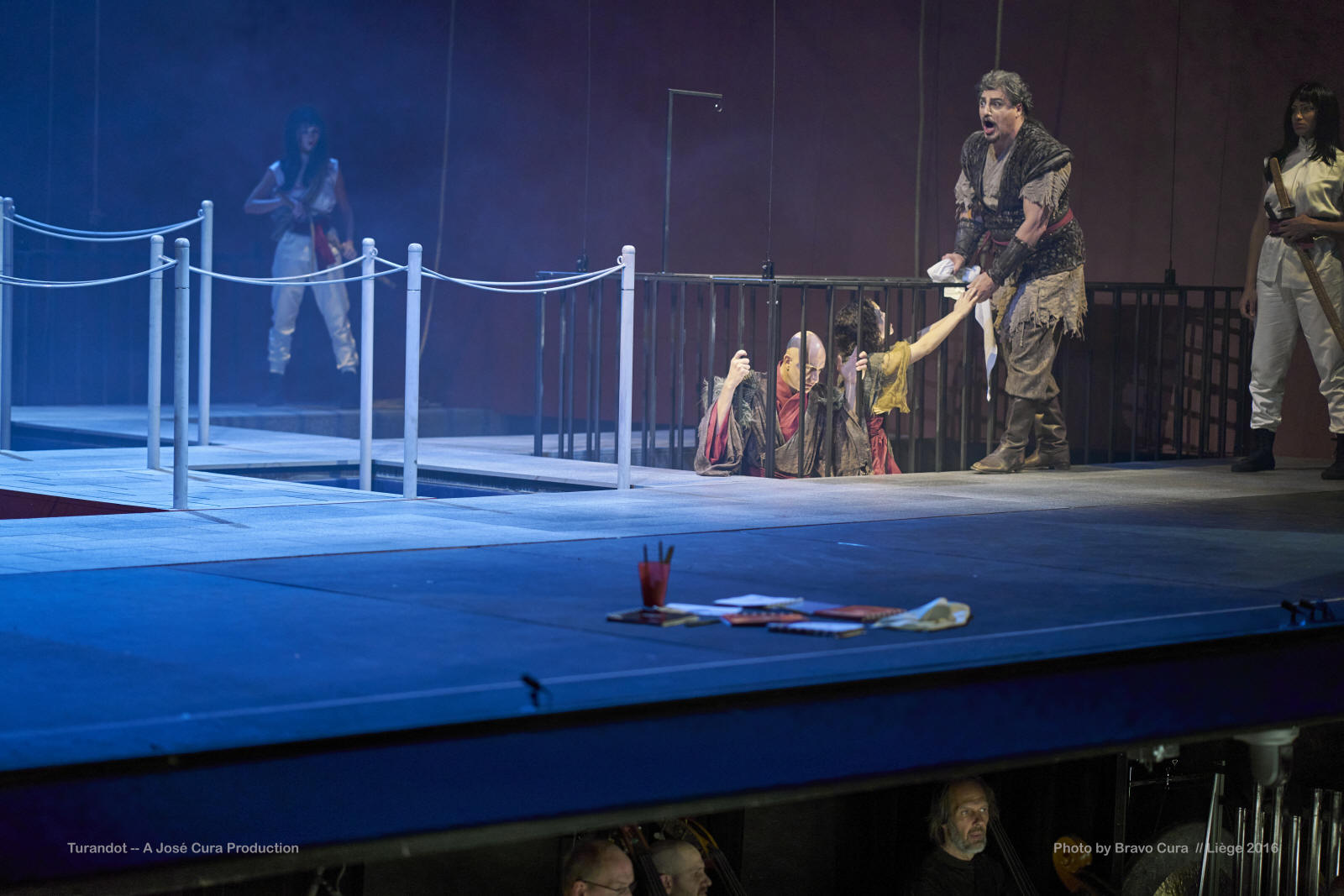

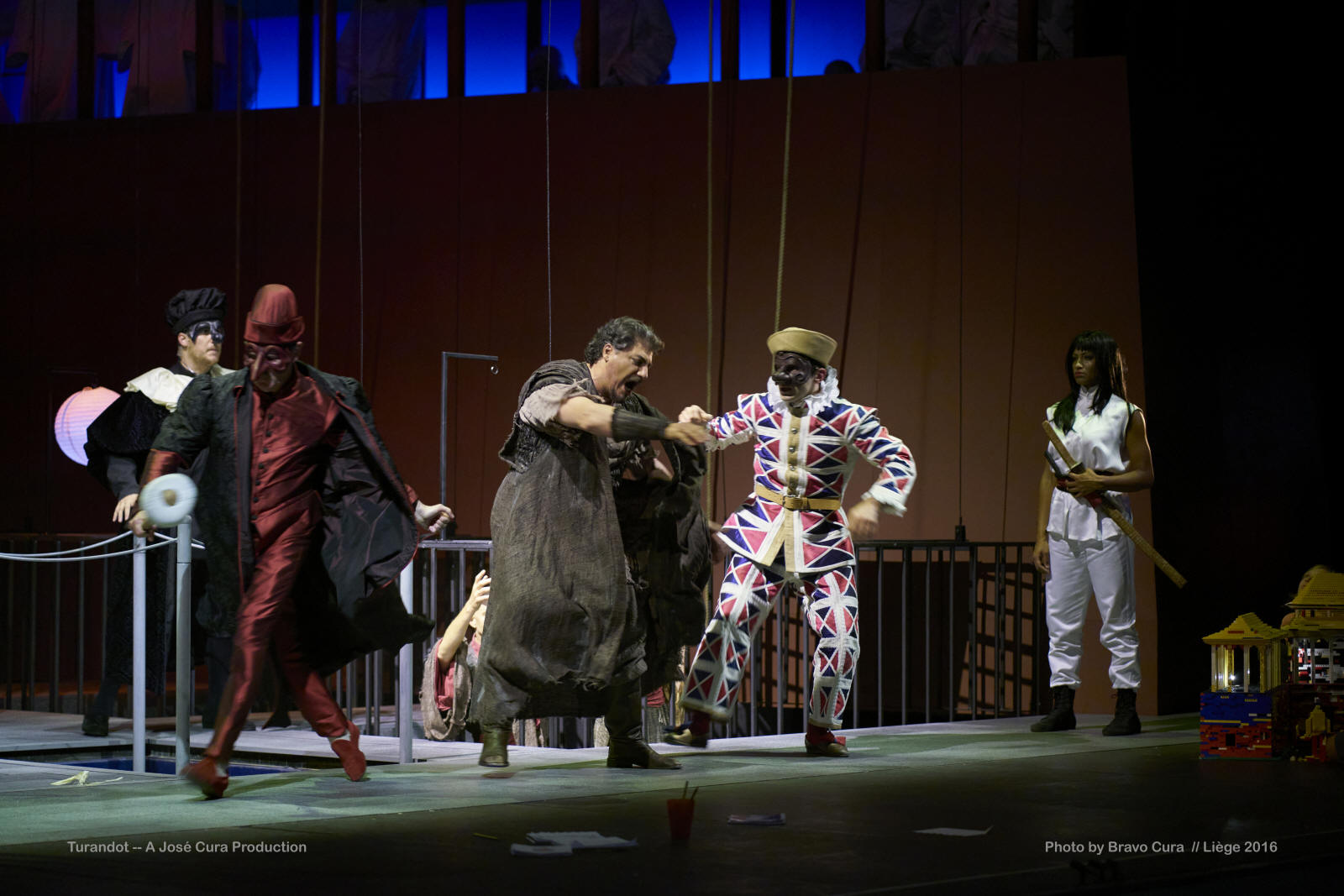

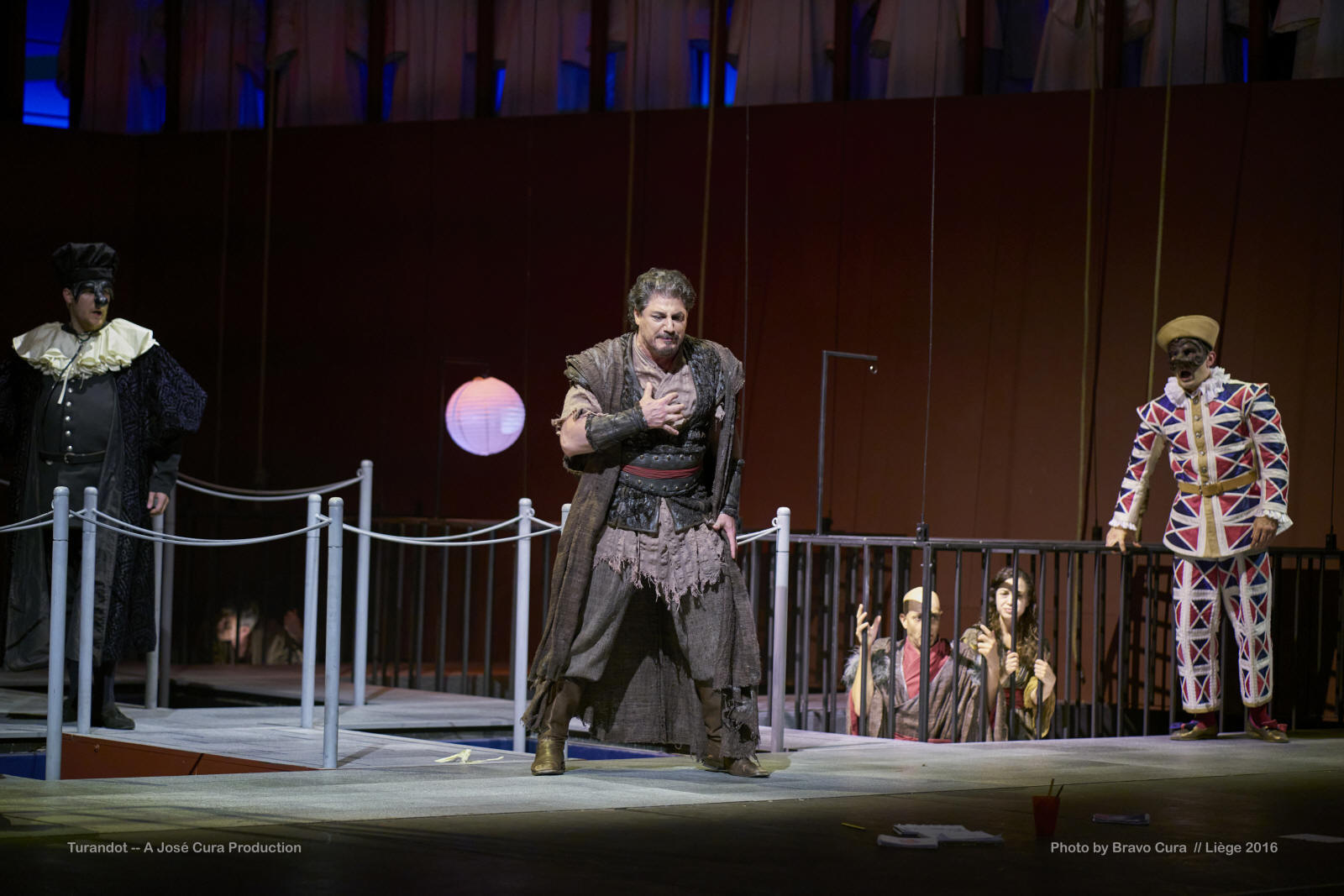

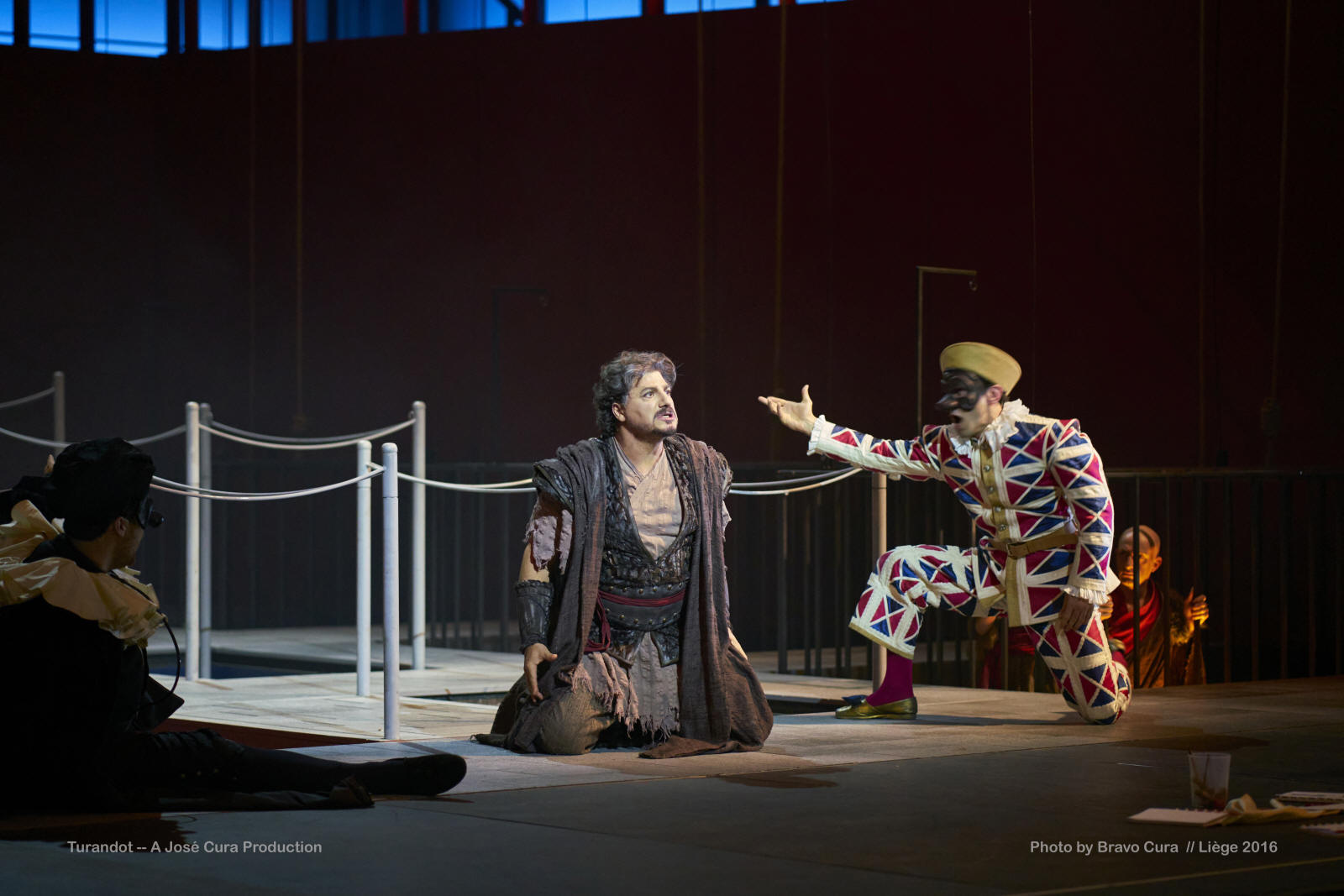

Turandot Opera News THE OPÉRA ROYAL DE LIÈGE opened its season with Puccini’s Turandot without the usual Alfano finale, but ending instead with the death of Liù. Toscanini had chosen this option for the work’s premiere, for, despite a few sketches by the composer, his death robbed us of knowing precisely how he would have dealt with the redemptive love of Calaf and Turandot. It is perhaps overly romantic to suggest that Puccini’s creativity was thwarted by the challenge of a happy ending. Renaissance man José Cura, was at once star tenor, director and designer of the show, with Paolo Arrivabeni conducting the Liège chorus and orchestra. When the audience entered the auditorium, children were busy making a Lego model of a temple and putting the finishing touches to paintings of the costumes. The Mandarin, baritone Roger Joakim, entered as an exasperated contemporary schoolteacher, cajoling his pupils into the telling of the ancient legend before donning his costume. The curtain then rose on a fairy tale image of the temple, inspired by the children’s imagination. It was a valid idea, but unfortunately the stylized temple looked rather too much like a 1950s take on chinoiserie than a cutting-edge concept. Cura’s best ideas came in his treatment of Ping, Pang and Pong—a trio of characters who often irritate rather than charm. He treated them as three principal characters of the commedia dell’arte, Pantalone, Arlecchino and Dr Balanzone, before dressing up in their official Chinese costumes for the riddles. This brought a darker brooding quality to the trio, who were even touching as they spoke of their past lives, led by the excellent baritone Patrick Delcour as Ping. Cura tried to cram too many tempting ideas into the final minutes of this shortened version. There is no music to accompany a last minute appearance of the dead composer, or Liù’s seemingly angelic pardon, but ending the opera with the poor girl’s death does put the opera in line with the heroines of La Bohème and Madama Butterfly. Liège was fortunate to have a scene stealing Liù in diminutive young American soprano Heather Engebretson. After a hesitant Act I aria, she reappeared with tragic poise and sweetly floated phrases for her climactic death scene, garnering the most applause from the first night audience on September 23, aided by some impassioned last-act singing from bass Luca Dall’Amico as Timur. This sentimental ending robs from Turandot her moment of transformation, somewhat sidelining the character—one suspects that neither the formidable Turandots of ages past, such as Eva Turner and Birgit Nilsson, would have gone with the plan. Tiziana Caruso’s sensual dramatic soprano made her seem a woman confused by her own sexuality, rather than an icy princess; her Turandot was intrigued by the arrival of the all-conquering Calaf, and shocked by the shattering reality of Liù’s death. In questa reggia and the climax of the riddle scene were spoiled by top Bs and Cs in which tension produced an unfortunate beat in her voice. Tenor Cura was in his very best form, however, with a secure heroic presence, and a roof raising Nessun dorma. Arrivabeni conducted a well paced performance but one lacking in orchestral detail; the chorus of children was excellent, their adult colleagues sounded in need of more voices. The production was dedicated to Cura’s friend and colleague, the recently deceased soprano Daniela Dessi, “Dany” to her friends. This was an evening of traditional vocal values, worthy of the artist who had made a number of appearances for this company. |

|

|

Act I

|

|

| Curtain Call and Backstage Photos

|

|

Note: This is a machine-based translation. We offer it only a a general guide but it should not be considered definitive.

Forum OpéraDominique Joucken 26 September 2016

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpt]

I n 1924, Puccini died in the middle of composing Turandot. The third act is incomplete: it lacks the great final duet, which must pit Calaf against the princess with the heart of ice who will ultimately capitulate in the face of victorious love. The only indication left by Puccini about this duet is written in the score, just after Liu's death: “e poi, Tristano” (“and then, Tristan”), an instruction that is both very vague and very precise. Franco Alfano initially, then Luciano Berio more recently, tried to complete the work. Neither of these attempts is fully convincing, as it is difficult to find the level of inspiration that the Tuscan master achieved in his ultimate opus.José Cura, known not only as a tenor but also as a director, opts for a radical solution: he stops the performance where Puccini laid down his pen, that is, at Liu's death and Timur's brief lament. Without revealing the secret of the staging to the future spectator, suffice it to say that he uses the last bars to allude to the fate of the composer himself. Is such an option satisfying? Not really. First, by concluding the evening with the sacrifice of the little slave girl, the staging shifts the opera's focus to a character who is ultimately secondary, and Turandot ultimately becomes the story of little Liu. Second, this musicological Jansenism deprives us of the final duet written by Alfano, generally adopted, which, if not written in musical finesse, nevertheless allows us to find an outlet for the tension built up during the piece. The cosmic accents of the final bars are catharsis-inducing. Apart from this questionable choice, the Argentine tenor's staging works rather well. It's a fairly classic production, faithful to the indications in the libretto. Over and above slavish illustration, José Cura succeeds in rediscovering the "Turandot tone" so unique in Puccini's career and therefore so difficult to define: that of an epic, choral work, in which China unfolds in all its magic, sensuality and cruelty. At the same time, kitsch - a common pitfall when it comes to Asia - is avoided thanks to extensive work on lighting and costumes. The ingenious way in which the children's choir is integrated into the action is particularly noteworthy. We wrote earlier of our regret at being deprived of the final duet. This was all the more frustrating as the Liège opera brings together two vocal monsters who would have had the capacity to shake the walls of the theater. Tiziana Caruso's Princess Turandot has the torrential breadth Puccini intended. She's an Isolde, a Brünnhilde, an Elektra, but without the vibrato that gnaws at many of these vocal battleships. She also knows how to lighten her emission in moments of tenderness, giving voice to half-tones that insinuate themselves into the memory by contrasting with the passionate outbursts that follow or precede. One can only imagine how this sea of ice would have melted in Calaf's arms. As for José Cura, he has lost (almost) nothing from his glorious recording period at the end of the 90s, when he performed Samson and Pagliacci without faltering. His voice is as full as ever, anchored in a physical and technical foundation that stands up to the test of time. You have to see him on stage, legs slightly apart, neck tucked between his shoulders, beginning to roar like a wild beast. The timbre has that baritone coloring, in the tradition of Ramon Vinay, and at the same time he has the ability to go for the high notes without distorting the voice. There was some frustration at the start of Act III with the famous Nessun dorma, when Cura seemed not to give his all. Was this an interpretive decision, a momentary fatigue or a desire to preserve himself for what was yet to come? It's hard to say, but the audience, galvanized by the performances in Acts I and II, was disappointed. In total contrast to Calaf's athletic figure, Heather Engebretson's Liu was so graceful and slender that she seemed to have stepped out of a children's choir. The voice was just as pure, fragile and diaphanous. At first, the format sounded a little "small," but the young American drew on her resources to get past the orchestra and touch the audience's heart in a death that closed the performance and allowed her to triumph on the applause meter. Luca Dall'Amico's Timur was a model of classical singing, a noble, powerful bass that lent his character emotion and gravity. Patrick Delcour, Xavier Rouillon and Papuna Tchuradze, all of whom are excellent actors, played the parts of Ping, Pang and Pong, which constantly blended comedy, lyricism and rhythmic vivacity. The chorus was committed and homogeneous but on this opening night, there were still many gaps. The orchestra of the Opéra Royal de Wallonie was visibly happy to play the sumptuous parts intended for it by Puccini at the height of his symphonic art. A little too enthusiastic, even, as conductor Paolo Arrivabeni sometimes had trouble containing the waves rising from the pit, which tended to drown out the singers. Will we complain that the bride is too beautiful? In conclusion, this Turandot is a captivating show and opened the opera season in Liège with great fanfare. The bar is set very high for the future. |

|

Turandot

LB [Computer-assisted Translation]

A faithful servant of Puccini, José Cura is so in more ways than one. Indeed, if we know the Argentinian for his operatic art, we may be unaware that he has been composing, conducting and directing for nearly ten years. He does so with seriousness and intelligence, as demonstrated by the house brochure, which links the story of the Ice Princess, rediscovered "when modern psychoanalysis asserted itself as an instrument of knowledge", with a creator who has always been very sensitive to the feminine. And Cura asks: "Is it possible that the reason he didn't complete the work, beyond his illness, was a very personal sense of unease at the 'settling of scores' between the masculine and feminine egos represented by Turandot's denouement?" In reference to the original fable, which is rich

in learning, he summons a group of children who, through their playful

activities upstage (painting, Lego, etc.), announce the work before

taking part in it (Dal deserto al mar). Far from sprawling out like

other productions, our "little" Imperial City rises towards the

arches to place the chorus in side galleries and bury its dungeons

under the stage boards, from which only the prisoners' torsos emerge

- creating an ingenious as symbolic sounding board. While the students

disguise their teacher as a Mandarin, three accomplices dressed

as ministers while also usually wearing Commedia dell'arte masks,

also link reality and fantasy. They are also the comic touch (phallic

sabers, Spiderman T-shirts, etc.) that breathes life into the sumptuous

but morbidly lit city. Paolo Arrivabeni was the talented master of an orchestra

with well-differentiated sections, at ease with the initial wildness

(episode of the Prince of Persia) as well as the sensuality of more

intimate scenes. The performance on 1 October will be dedicated

to one of Cura’s former partner, the divine Daniela Dessì, who passed

away on August 20th. |

Act II

|

v

v

|

|

Liège Opera starts the new season with a brilliant premiere of Turandot

BRF Hans Reul 26 September 2016

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpt]

Nessun dorma is a hit among opera arias. This aria has been known to everyone since the Three Tenors' stadium concerts. And it is one of the many highlights of Puccini's opera Turandot, which is now being performed at the Royal Opera of Wallonia in Liège.

Puccini's operas are among the most frequently performed in the repertoire, including this story of the Chinese princess Turandot, who only wants to marry the person who can answer her three questions. Many failed and had to pay with their lives. But now the Tartar prince Calaf appears and successfully solves the three riddles. Turandot doesn't want to marry him but her father points out the law that requires it; however, Calaf intervenes and gives her a riddle of his own: find out his name. The slave Liu knows the answer but refuses to say it and before she is forced to do so under torture, she kills herself.

Puccini had composed his work up to this point. After his death Franco Alfano was asked to compose a finale in which Calaf and Turandot come together. But was this really what Puccini wanted? José Cura and Liège opera director Stefano Mazzonis think no, and for that reason they end the opera with Liu's death.

Turandot is designed by director Cura as a fairytale opera, as a fable. So before the curtain rises, he has a group of children build the large gate of the forbidden city on the forestage using, among other things, Lego blocks, as the story is told to them. And if you look at the world of fairy tales, you'll notice that many fables are quite cruel.

The moral of Turandot is that Liu gains her strength through love and so the final scene chosen here becomes more logical. Liège has been able to engage a wonderful Liu with the young Heather Engebretson. The way she shapes and sings the role leaves no one unaffected. She was rightly celebrated by the audience. As was, of course, José Cura, who not only directed the production but also sang Calaf. Cura is still one of the leading tenors of our time and demonstrated that by singing the role with powerful brilliance. Tiziana Caruso, on the other hand, was less convincing as Turandot in the incredibly demanding role.

Conductor Paolo Arrivabeni has often proven that he is a connoisseur of the Italian repertoire. This time, too, he was able to bring out the colors of Puccini's score. He did not shy away from the fortissimo passages. The orchestra was so large that the percussion even has to be placed in one of the side boxes. The choir takes its place in the galleries of the stage, which Cura had built as an impressive backdrop. Considering that Puccini wanted a choir of 100 singers, it is understandable that the Liège choir sounded a little thin at times. On the other hand, the performance of the Liège Opera's children's and youth choir was magnificent and deserves special mention.

|

|

|

Act III

"Requiem" for LiùOpernnetz 23 September 2016 Pedro Obiera

[Computer-assisted translation // Excerpt]

José Cura, one of the best-known tenors in the Italian repertoire, is one of the few singers who can also hold his own as a director and look far beyond the boundaries of his singing career. His close friendship with the artistic director of the Opéra Royal de Wallonie in Liège, Stefani Mazzonis di Pralafera, has now brought the tenor to the Belgian city for the second time, where he is not only directing Puccini's last opera Turandot, but also creating the stage design and taking on the role of Calaf.

Even if the history of the work's reception does not need to be rewritten with this new production at the effective start of the season, Cura's production offers more than just an exotically colorful or even irrelevant chinoiserie as recently seen in Bregenz, free from the silly antics of the bizarre trio of ministers. Although he remains loyal to the spirit of Carlo Gozzi’s fairy-tale character, his reading of fairy tale suggests that it is a passionate plea for the inviolability of true love. And Cura celebrates the slave, Liù, who dies for her love, not the cold-blooded Chinese princess. Consequently, he ends with the fragment of the unfinished and renounces the sumptuous wedding and happy-ever-after ending of the blue-blooded princely couple that Franco Alfano added after Puccini's death. Cura’s work ends with the tragic yet tender death of the Liù, the last original sounds from the composer's pen.

Darkness dominates the entire production. Representational architecture of the "forbidden city" is weakly illuminated. The extras and most of the singers are dressed in muted colors. Only a group of the princess's brutal female henchmen appear in white and Turandot herself appears in a crisp white trouser suit, initially veiled and in the role of executioner. The trio of ministers only don richly decorated Chinese robes in the riddle scene.

[…]

Cura thus creates tension, particularly in the first and third acts, while he leaves much to chance in the dramaturgically and musically weaker second act, especially the riddle scene. Overall, however, following his successful productions of Cavalleria rusticana and Pagliacci at the same venue a few years ago, he has once again produced a very pleasing work.

And the musical quality is impressive anyway. The success [of this Turandot] is guaranteed, of course, when Cura uses his powerful and radiant voice—and not only when he triumphs in the famous Nessun dorma. He is the star of the evening. Heather Engebretson matches the importance Cura attaches to Liù, filling the role with lyrical warmth and becoming the star of the evening alongside Cura. Tiziana Caruso's voice in the title role, which sounds very hard in the high notes, has a hard time matching these performances.

If you add Luca dall'Amico's robust bass as Timur and the well-cast trio of ministers, the vocal quality is good, and that is saying a lot given the difficulty of casting the piece. While the choirs, some of whom are far away from the orchestra, still had to struggle with coordination problems in the premiere, the Liège orchestra under the expert direction of Paolo Arrivabeni provides both pithy and sensitive tones. The children's choir sings cleanly and succinctly and deserves special praise.

The audience thanks them all with long-lasting, enthusiastic applause for a Puccini production that is well worth hearing and overall seeing, with a cast that far surpasses that of the Deutsche Oper am Rhein by a long way.

|

|

José Cura staged Turandot at the Opéra Royal de Wallonie Opera Online 1 October 2016 Emmanuel Andrieu

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpt]

To open its 16/17 season, the Opéra Royal de Wallonie entrusted the renowned Argentinian tenor José Cura with the task of staging Turandot, having already proved his talents as a director - in loco in 2012 - with the Cavalleria rusticana / Pagliacci double bill. He also designed the sets which, although rather sober and stylized, could be described as traditional and attractive. As in the production seen this summer at the Peralada Festival, Cura chose to end the work after Liù's death, retaining neither Alfano's nor Berio's finale. Instead, he took advantage of the final moment in the score to pay tribute to the composer: Timur arrives on stage dressed as Puccini and accompanied by members of the chorus dressed as Puccinian heroes, including Tosca, Minnie, Rodolfo, Suor Angelica and Cio-Cio San. And why not?

In the title role, Sicilian soprano Tiziana Caruso is a revelation: her powerful voice unfolds with impressive authority and intensity, yet is capable of nuance, control and grace when required. Even if his high notes lack the power and stamina of yesteryear, José Cura is a first-rate Calaf, with a vocal palette of warm, baritone colors and a very natural stage presence. American soprano Heather Engebretson brings to Liù an unusually full-bodied timbre for this part, but also an innate sense of Puccinian phrasing and a touching intensity, while Italian bass Luca Dall'Amico, with his warm voice and paternal temperament, finds in Timur a job that suits him. We also enjoy the trio of ministers (Patrick Delcour, Xavier Rouillon and Papuna Tchuradze), who romp so happily (and with commendable precision) in the complicity of their characters that they prove irresistible. Emperor Altoum (Gianni Mongiardno) and The Mandarin (Roger Joakim) are also well served.

Last but not least, Italian conductor Paolo Arrivabeni - in his last season at the helm of the Orchestre de l'Opéra Royal de Wallonie-Liège - holds the whole performance together, infusing it with a vitality that flows generously. The Opéra Royal de Wallonie-Liège's Chorus and Maîtrise not only give their all, but also skillfully fill the stage, starting with the children, to whom Cura gives a prominent place in his stage direction.

|

|

Turandot

Opera January 2017 Erna Metdepenninghen

Belgium Liège The Opéra Royal de Wallonie opened the season with Puccini’s Turandot (October 1), conducted by its music director Paolo Arrivabeni and directed by José Cura, who also designed the sets and sang the part of Calaf. The opera was given in its unfinished state as left by the composer at his death, ending with the death of Liù and the short lament of Timur. So there was no conquest of Turandot by Calaf and no triumphant finale. Instead Timur (apparently no longer old and blind) quickly marched off into the wings only to reappear shortly afterwards dressed as Puccini to lie down and die next to Liù, surrounded by characters from his different operas. Not such a good idea, if you ask me. The opera now seemed more about Liù than Turandot; both the Alfano and the Berio endings bring about the necessary catharsis. Cura tried to combine fairy tale, orientalism and commedia dell’arte in his rather static staging. The opera started as a play for and by children under the guidance of a teacher who became the Mandarin. There was no exotic kitsch, no sumptuous palace and a severe but nonetheless alluring Principessa Turandot. Tiziana Caruso tackled this exacting part with ease, combining vocal fire with subtle nuance in her ample, rich soprano. It was a shame she wasn’t allowed the final duet. Cura was a self-assured, heroic Calaf, capable of compassion and singing with strong, shining, well-controlled tone. Heather Engebretson cut a tiny, childish figure as Liù and made the most of her confrontation with Turandot in the third act, but her clear soprano was too light and small for the role. Luca Dall’Amico sang Timur in a noble bass; the three ministers were well portrayed by Patrick Delcour, Xavier Rouillon and Papuna Tchuradze; and Roger Joachim was a sonorous Mandarin.

|

|

|

|

Liège Opera starts the new season with a brilliant premiere of Turandot

BRF Hans Reul 26 September 2016

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpt]

Nessun dorma is a hit among opera arias. This aria has been known to everyone since the Three Tenors' stadium concerts. And it is one of the many highlights of Puccini's opera Turandot, which is now being performed at the Royal Opera of Wallonia in Liège.

Puccini's operas are among the most frequently performed in the repertoire, including this story of the Chinese princess Turandot, who only wants to marry the person who can answer her three questions. Many failed and had to pay with their lives. But now the Tartar prince Calaf appears and successfully solves the three riddles. Turandot doesn't want to marry him but her father points out the law that requires it; however, Calaf intervenes and gives her a riddle of his own: find out his name. The slave Liu knows the answer but refuses to say it and before she is forced to do so under torture, she kills herself.

Puccini had composed his work up to this point. After his death Franco Alfano was asked to compose a finale in which Calaf and Turandot come together. But was this really what Puccini wanted? José Cura and Liège opera director Stefano Mazzonis think no, and for that reason they end the opera with Liu's death.

Turandot is designed by director Cura as a fairytale opera, as a fable. So before the curtain rises, he has a group of children build the large gate of the forbidden city on the forestage using, among other things, Lego blocks, as the story is told to them. And if you look at the world of fairy tales, you'll notice that many fables are quite cruel.

The moral of Turandot is that Liu gains her strength through love and so the final scene chosen here becomes more logical. Liège has been able to engage a wonderful Liu with the young Heather Engebretson. The way she shapes and sings the role leaves no one unaffected. She was rightly celebrated by the audience. As was, of course, José Cura, who not only directed the production but also sang Calaf. Cura is still one of the leading tenors of our time and demonstrated that by singing the role with powerful brilliance. Tiziana Caruso, on the other hand, was less convincing as Turandot in the incredibly demanding role.

Conductor Paolo Arrivabeni has often proven that he is a connoisseur of the Italian repertoire. This time, too, he was able to bring out the colors of Puccini's score. He did not shy away from the fortissimo passages. The orchestra was so large that the percussion even has to be placed in one of the side boxes. The choir takes its place in the galleries of the stage, which Cura had built as an impressive backdrop. Considering that Puccini wanted a choir of 100 singers, it is understandable that the Liège choir sounded a little thin at times. On the other hand, the performance of the Liège Opera's children's and youth choir was magnificent and deserves special mention.

|

|

Turandot in the intimacy of the ORW Le Soir 28 September 2016 Serge Martin

[Computer-Assisted Translation // Excerpt]

The staging brings out all the colorful and luminous freshness of the tale Turandot, with its multiple crowd scenes, is a spectacular opera displayed with brilliance in large theaters (Lehnhoff's staging in Amsterdam and at La Scala is memorable) or in gigantic open-air stages like the Chorégies d'Orange. This extravaganza of effects often makes us forget that this opera is above all a tale inspired by Puccini by a play by Gozzi. And it is the great merit of José Cura's works in Liege (the Argentinian tenor is making a habit of staging his own shows and doing so very well) that he rediscovered the true essence of the tale when set in the intimacy of a small stage. His geometrically spare set evoked the Imperial City, then illuminated it in a thousand colors (Oliver Wéry's lighting is one of the show's great assets). […] But beware: the action is lively, often fiery, between the arrogant ice of Turandot (Tizianna Caruso) and the compassionate fire of Calaf (José Cura). In the small theatre setting, vocal delights shine through, right down to the moving tenderness of American Heather Engebretson's Liu, the revelation of the evening. Luca dall'Amico's Timur is vigorous and the three ministers (Patrick Delcour, Xavier Rouillon and Papuna Tchurdze) are committed. But this vibrant tone would not be possible without Paolo Arrivabeni's dynamic conducting, to which the chorus responds with nobility. And suddenly, Puccini's last, sumptuous opera (what music! what an orchestra!) takes on an essentially human dimension, for the tale speaks to us of our fears and fantasies. And this humanity is all the more obvious since Stefano Mazzoni, like Toscanini, decided to stop the opera the moment Puccini stopped writing (he died in Brussels before completing it). A character dressed all in black (a repurposed Timur), comes to lie down between the lamp at the front of the stage to die. So, in the end, it's neither Turandot nor Calaf who triumph, but the pure, tender Liu. Beautiful and moving.

|

|

Puccini's end Online Musik Magazin Thomas Molke September 2016

[Computer-assisted Translation // Excerpt] Although Turandot is one of Giacomo Puccini's best-known operas, not least of which is due to the famous tenor aria Nessun dorma, it places high demands on theaters when it comes to complete performances, and not just because the primary roles are difficult to cast. In addition, Puccini was also unable to complete this opera, leaving behind only 36 sketch sheets at his death which follow the events after Liù's suicide, and the final duet for Turandot and Calaf had not yet been orchestrated. Under pressure from the publisher and the Prime Minister, Puccini's student Franco Alfano finally agreed to complete the opera based on the sketches. Nevertheless, since then musical theaters have struggled with the dramaturgically and musically questionable ending. Toscanini stopped the premiere of the opera after Liù's death with the words: "At this point the maestro died." Alfano's additions were only available in an abridged version at the second performance. Since the complete ending was first performed in the 1980s, there have always been different versions of the opera's ending. Now in Liège José Cura, who impressed here four years ago in Cavalleria rusticana and Pagliaci in the dual role of director and singer, has taken on Puccini's unfinished opera and found his own unique interpretation of the ending. He has the composer himself appear at the end and puts Timur's last words into his mouth after Liù has killed himself. Whether it really is a suicide in Cura's production is debatable, as it is not entirely clear whether the slave girl really throws herself into the sword drawn by Turandot or whether Turandot stabs her from behind. That Turandot feels complicity can be seen from the fact that she then desperately tries to clean her hands of the (imaginary) blood. Puccini now enters this scene, and suddenly his famous stage characters such as Madama Butterfly, Mimi, Tosca, the Girl from the Golden West, Suor Angelica and various others appear to bid a sad farewell to their creator. Puccini lies down between red and white paper lamps on the stage ramp and ends the piece with his death. The work thus comes to a close without a questionable happy ending. Apart from this reinterpretation of the opera's ending, Cura chooses a classical approach for his production. As a framework, he introduces a school class that is working on a project about Puccini's opera before the actual performance begins. The younger children have designed a three-part pagoda out of cardboard, which will later frame the stage set designed by Cura. The older girls have been working on the costumes for the three ministers and have drawn three figures from the commedia dell'arte on the stage wall, which replaces the curtain, to represent the three ministers Ping, Pang and Pong. They initially appear in everyday clothes with a suitcase containing the respective costume sketched on the wall. A teacher (Roger Joakim) appears and examines the pupils' work before he transforms himself into the Mandarin with an oriental jacket and sets the actual opera plot in motion with the announcement that Turandot will only marry a suitor who can solve her three riddles. The wall is drawn upward into the rigging loft and provides a view of a huge three-part Pagoda dates. The chorus, dressed in oriental-style costumes by Fernand Ruiz, is placed quite statically in the background. In the middle of the stage are numerous cages in which the suitors for Turandot's favor, as well as Liù and Timur, are held captive though not clear why, since the later, Timur, the dethroned king, wanders through the streets like a beggar, free to move as he wishes. To emphasize Turandot's rejection of the male sex, she surrounds herself with various female fighters in manga costumes. The glamour of the Princess is underlined by Olivier Wéry skillful lighting. In her white costume in the glistening bright light of her first appearance, she looks like an angelic figure, which makes it understandable that Calaf falls in love with her, especially as she drops her veil in front of his cage. Although Liù snatches this veil from Calaf shortly afterwards, she is unable to free him from his fascination for this man-killing woman. For the three riddles that Turandot poses to Calaf, three passageways are raised from the stage floor in the middle of the stage one behind the other, with a paper curtain closing the last passageway each time a riddle is solved. In the end, Turandot has no way of escaping Calaf, especially as her father announces that she must keep her promise to marry the one who can solve all three riddles. But Calaf offers her another way to escape him by cutting through one of the paper curtains. If she finds out his name by dawn, he is prepared to die for her. Musically, the evening is of a high standard. Paolo Arrivabeni finds a fresh approach to Puccini's music with the orchestra of the Opéra Royal de Wallonie and leads the ensemble through the evening with a light hand, without overdoing the dramatic passages. This gives the production a slender sound and reduces the "battle" between singers and orchestra that often arises in this opera. The opera chorus under the direction of Pierre Iodice and the children's chorus give a solid performance. Patrick Delcour, Xavier Rouillon and Papuna Tchuradze are musically and dramatically convincing as Ping, Pang and Pong - although whether you need a manga T-shirt, a Spiderman costume and a brassiere with a fatsuit is a matter of taste - before donning classic oriental garments. Roger Joakim is a safe bet as the Mandarin and class teacher with his powerful baritone. Luca Dall' Amico, as the dethroned King Timur, makes us sit up and take notice with his distinctive bass. Only his acting still seems too agile in places for the decrepit father. As Puccini, he demonstrates great stage presence at the end of the evening. Tiziana Caruso may not have yet properly adjusted to Arrivabeni's careful conducting. In any case, she sings Turandot's great aria with an exaggeratedly powerful voice and far too much vibrato, so that at one point it even wobbles slightly in the high notes. A little less would have been more here. On the other hand, Heather Engebretson as the slave Liù is an absolute audience favorite. With cleanly intoned, crystal-clear high notes, she thrilled the audience in her big scene in the second act, when she desperately tries to dissuade Calaf from taking the riddle test, and moved the audience in her big final scene, when she is prepared to die for Calaf. As the opera also ends at this point, it almost deserves the title Liù rather than Turandot. Cura not only proves that he has a convincing approach to Puccini's unfinished opera as a director, but also shines in the demanding role of Prince Calaf. With tenoral sheen and a furious "Vincerò", he recreates the famous Nessun dorma and works with the conductor to rush forward so that applause does not to interrupt the musical flow. . Cura also passionately sings Calaf's Non piangere, Liù in the second act with an agile tenor and magnificent high notes. At the end, there is long-lasting and frenetic applause for everyone involvedHier wäre ein bisschen weniger mehr gewesen. CONCLUSION José Cura once again proves his versatile talent in Liège by not only shining as a singer in Puccini's Turandot, but also as a director who brought a convincing approach for completion of the work.

|

|

v

|

|

|

|

Turandot, Liège, September and October 2016: “It stops with the death of Liù, where Puccini stopped. For the new staging of Turandot at Liège, it was decided to present the original unfinished version, as Arturo Toscanini had chosen to direct for the first performance at La Scala in 1926. Tenor José Cura, who plays Calaf but is also the director and creator of production, elected to end with a moving tribute which included the Puccini and his most famous characters who come to accompany him on the last trip. Cura confirmed his perfect mastery of the part [of Calaf] but as a director and set designer showed many ideas, from traditional to modern, mixed together on the scene of a stylized imperial palace.” Il Giornale Della Musica, 26 September 2016

Turandot, Liège, September and October 2016: “Cura was a self-assured, heroic Calaf, capable of compassion and singing with strong, shining, well-controlled tone.” Opera, January 2017

Turandot, Liège, September and October 2016: “Renaissance man José Cura was at once star tenor, director and designer of the show. Cura’s best ideas came in his treatment of Ping, Pang and Pong—a trio of characters who often irritate rather than charm. He treated them as three principal characters of the commedia dell’arte, Pantalone, Arlecchino and Dr Balanzone, before dressing up in their official Chinese costumes for the riddles. This brought a darker brooding quality to the trio, who were even touching as they spoke of their past lives, led by the excellent baritone Patrick Delcour as Ping. Tenor Cura was in his very best form, however, with a secure heroic presence, and a roof raising Nessun dorma. This was an evening of traditional vocal values, worthy of the artist who had made a number of appearances for this company.” Opera News, November 2016

Turandot, Liège, September and October 2016: “[Rightly celebrated], of course, was José Cura, who not only directed the production but also sang Calaf. Cura is still one of the leading tenors of our time and demonstrated that by singing the role with powerful brilliance.” BRF, 26 September 2016

Turandot, Liège, September and October 2016: “More than merely slavish illustration, José Cura succeeds in recovering the “Turandot tone” so unique to Puccini’s career and so difficult to define: that of an epic choral work in which China unfolds in all its magical sensuality but also its cruelty. At the same time, the kitsch—a pitfall so common when it comes to Asia—is avoided by thorough work on lighting and costumes. The ingenious way in which the children’s choir is integrated into the action deserves to be highlighted. José Cura has lost (almost) nothing from his glorious period on discs in the late 1990s, where he played the chained Samson and Pagliacci without flinching. The voice is always ample, fastened to physical and technical bases at all times. He must be seen on stage, his legs slightly spread, his neck tucked between his shoulders, beginning to roar like a wildcat. His timbre has a baritone coloring, along the lines of a Ramon Vinay, at the same time having the ability to go for the high notes without bleaching his voice. In conclusion, this Turandot was a captivating show, one which opened with great fanfare the opera season at Liège. The bar has been placed very high for the sequel.” Forum Opéra, 23 September 2016

Turandot, Liège, September and October 2016: “José Cura was a first-rate Calaf, with a vocal palette of warm, baritonal colors and a very natural stage presence.” Opera On Line, 1 October 2016

Turandot, Liège, September and October 2016: “The success [of this Turandot] is guaranteed, of course, when Cura uses his powerful and radiant voice—and not only when he triumphs in the famous Nessun dorma. He is the star of the evening. The audience offered thanks for the musicality, production, and cast that towers over others.” Opernnetz, 23 September 2016

Turandot, Liège, September and October 2016 // Director: “José Cura, one of the best-known tenors in the Italian repertoire, is also one of the few singers who can assert himself as a director and, in doing so, look far beyond the bounds of the singer's life. The tenor is now in Liège, where he not only directs Puccini's last opera, Turandot, but also creates the stage design and performs the role of Calaf. Cura’s production offers more than just an exotic, colorful or irrelevant chinoiserie. Although he remains loyal to the spirit of Carlo Gozzi’s fairy-tale character, his reading suggests that it is a passionate plea for the inviolability of true love. And Cura celebrates the slave, Liù, who dies for her love, not the cold-blooded Chinese princess. Consequently, he ends with the fragment of the unfinished and renounces the sumptuous wedding and happy-ever-after ending of the blue-blooded princely couple that Franco Alfano added after Puccini's death. Cura’s work ends with the tragic yet tender death of the Liù, the last original sounds from the composer's pen.” Opernnetz, 23 September 2016 Turandot, Liège, September and October 2016: “Musically, the evening was at a high level. Not only does Cura prove he has a compelling approach as a director to Puccini's unfinished opera but he also excels in the demanding role of Prince Calaf. With tenoral sheen and a furious "Vincerò", he recreates the famous Nessun dorma and works with the conductor to rush forward so that applause does not interrupt the musical flow. This comes after Calaf's Non piangere, Liù in the second act in which Cura sings with moving passion and magnificent high notes. At the end there was long-lasting and frenetic applause for everyone involved. Bottom line: José Cura once again proves his versatility in Liège, not only as a singer in Puccini's Turandot, but also as a director who brought a convincing approach for completion of the work.” Online Musik Magazin, September 2016

Turandot, Liège, September and October 2016: “Vocally, the heroic tenor embodied a committed Prince Calaf, from his crazy gamble at the end of the first act, punctuated by three great gong strokes, through his long-awaited Nessun dorma with its final, long held "Vincero." A masterful production.” Crescendo, 11 October 2016

Turandot, Liège, September and October 2016 // Director: “The famous - and often sulphurous - director Calixto Bieito had already tried to bring an original solution to the unfinished finale of Puccini's Turandot: in Toulouse, in 2015, he let the singers finish the performance in evening dress. Here in Liège, José Cura goes further: he radically removes the usual Alfano finale and leaves the score in the state it was in on November 29, 1924, the day of Puccini's death in Brussels. The opera ends with the death of Liu. During the brief lament that follows, Timur transforms into ... Puccini, who stretches and dies among his [opera] characters. A little girl crosses his hands on his chest. The moment is moving. The Argentine tenor is an excellent director, which the Liege audience had already noted in his diptych Cav / Pag. Struck by the Imperial Gate at the Forbidden City in Beijing, Cura recreates it in a sober way: a U-shaped building, leaving a place for the choir, essential character of the work, and placed simply to the left and to the right of the gate. The management of actors is effective; as a bonus, lights (Olivier Wéry) and costumes (Fernand Ruiz) make an important contribution to the oriental atmosphere. Except for a few puerile details (ministers undressing to reveal underwear inspired by comic books, large multicolored plastic balls representing the jewels offered to Calaf), the visual aspect was a new stage success for Cura. A masterful production.” Crescendo, 11 October 2016

Turandot, Liège, September and October 2016: “Dramatic tenor José Cura was both the opera’s hero Calaf and stage director. The Argentine tenor opted to do away with the typical clutter and chinoiserie that is the norm in productions of Puccini’s last work and masterpiece. Drawing on the fairy tale origin of the story, Cura sets the piece as a school project by children who design a Forbidden City using Lego, design the costumes including those of their teacher and narrator who is transformed into the Mandarin. [As a singer] José Cura had the humility to not put himself at the center of the production: he underplayed his role to focus on Turandot and Liù, thus emphasing the dark and light sides of desire. Cura had the required heroic voice and had no difficulty with the high notes [and with] the color of a true dramatic tenor.” ConcertoNet, September 2016

Turandot, Liège, September and October 2016: “José Cura played the leading male role, Calaf, son of Timur. He has deservedly received many awards and it is not surprising that he has been Kammersänger of the Viennese Opera since 2010. As a specialist in Verdi and Puccini, he took on this role with the necessary strength, desire and love, radiating a measured dramatic effect. He voiced all the vocal qualities in a magisterial way, without exaggeration in the high notes. Turandot is vocally a very difficult opera to sing because of the sometimes extremely heavy, rapidly changing vocal parts where technically the extreme is required. For Calaf, this was not a problem and José Cura may be safely counted as among the best interpreter of this role. [At the end] there was only one possible conclusion: this Turandot was without a doubt a splendid accomplishment that could equal that of the Scala or the Met. Performances of this level place the Opéra Royal de Wallonie Liège on a larger international level and make us want to attend other productions of this opera house.” Klassiek-Centraal, 11 October 2016

Turandot, Liège, September and October 2016 // Director: “In Liege not only was pure Puccini performed, but it became a true Puccini party. The staging and decors were completely suggestive, not excessive as sometimes happens in Butterfly or Turandot. Responsible for this was the Argentine Cura, who not only made himself credible as a world-famous dramatic tenor but also acts as a conductor (his original training), composer, set designer and photographer. Costumes and decors were as good as they were tasteful and the dramatic movements were evocative and expressive where necessary. The choir acted as an independent character, as in a Greek drama—again a perfect choice by Cura. Although Puccini wrote for a large number of voices here, this approach (with the chorus grouped and raised) was better; the attention remained with the three central players, Calaf, Turandot and Liù, the choir and orchestra. The only possible conclusion: this Turandot was without a doubt a splendid accomplishment that could equal that of the Scala or the Met. Performances of this level place the Opéra Royal de Wallonie Liège on a larger international level and make us want to attend other productions of this opera house.” Klassiek-Centraal, 11 October 2016

Turandot, Liège, September and October 2016: “Faithful servant of Puccini, José Cura was here in more than one role. Indeed, although the Argentinean is known for his operas, perhaps some are unaware that he composes, conducts, and for the last ten years has been staging operas. He does so with seriousness and intelligence. In reference to the original fable, Cura convened a group of children, who through a series of fun activities (painting, Legos, and so on) on the front edge of the stage announced the book ("Dal deserto al mar"). Rather than spreading outward, the Imperial City rose toward the rafters to allow the choir to be placed in the side galleries and ‘buried’ dungeons in the stage floor with little more than the torsos of the prisoners shown—creating an ingenious sounding board as much as a symbolic jail. While the students dress their teacher as the Mandarin, three accomplices wearing the masks usually associated with Commedia dell'arte arrived to further connect reality and fantasy as the Ministers [Ping/Pang/Pong]. They offered the comic touch (phallic sword, Spiderman t-shirt)… Dressed without exotic kitsch, strong singers surrounded José Cura (Calaf), a tenor of flawless strength but with heartbreaking tenderness when he whispered Dimmi il mio nome.” Anaclase, 27 September 2016

|

|

BravoCura Review For reasons never (success)fully articulated, management at the Opéra Royal de Wallonie elected to break with nearly 100 years of tradition to offer a truncated version of Giacomo Puccini’s last masterpiece, Turandot, despite the great composer’s deathbed plea that the work be performed only after it was completed. The result was a production that promised much, delivered a great deal, but in the end failed to satisfy. The house made one correct decision: they hired the best possible director to stage the abbreviated opera, one who knows this work intimately and whose fertile imagination overcomes obstacles that would stymie lesser artists. José Cura, who also designed the set and sang the role of Calaf, approached the work with a deep understanding of Puccini’s motivation and a reverence for both book and composition. His plan seemed admirably sensible but hardly simplistic: it took creativity and vision to slice open the stage floor to invoke the horror of Turandot’s reign while introducing the element of school kids learning about the ancient story and occasionally interacting with the characters. Incorporating tradition while breaking boundaries distinguishes many of Cura productions and this Turandot could have been a model of timelessness, if only….. Unfortunately, the mandated abbreviation distorted the narrative beyond the director’s control, shifting the dramatic momentum from Turandot to Liù. And without the final confrontation between Calaf and Turandot (the only time they are alone) and its triumphant conclusion the audience was left in limbo, denied the catharsis that comes with the resolution of the drama. Cura crafted as fine an emotional ending as possible under the circumstances, but it wasn’t Turandot. As a singing actor, Cura managed a unique interpretation which added depth to Calaf, a character too often portrayed as a shallow, ruthless, cold-blooded brute. The Argentine is thoroughly familiar with Puccini’s heroes: he, more than most, seems to understand that this last opera was the culmination of the Puccini male / female dynamic, the logical next step from the composer who created the heroic Mario Cavaradossi in Tosca and the girl who had never given away a kiss in Fanciulla. The yin / yang of Turandot and Liù, the two extremes of femininity, can convince only if the object of their love is truly worthy. As played with nobility and sensitivity by Cura, this Calaf certainly is: he steadfastly remains principled and honorable, treating his father with love and respect and a slave girl and a princess with equal dignity and kindness, evincing fearlessness in the face of death and offering grace when he could have claimed victory. Vocally, Cura was remarkable, singing with security, freely unleashing the immense power of his voice but just as easily pulling it back to release it as spun silk when needed. The private moment between Turandot and Calaf at the end of Act II, when he takes pity on her, was a moment of sheer beauty and indelible sweetness. Surprisingly, Nessun dorma, sung with an intensity approaching anger, was less successful, not in quality but in character. Turandot is an intimidating role, one of the most difficult that a dramatic soprano can perform, with the vocal fireworks often reduced to screams rising above the orchestra; few who attempt it survive unscathed. Tiziana Caruso managed the vocally fiendish role with skill and mostly succeeded; she was less convincing as an actress. In this production, Turandot picks Calaf as her next suitor and so there is, from the beginning, a certain connectivity and inevitability inherent in their relationship. Caruso was unable to bring that shading to her characterization, perhaps interpreting too literally her ice princess. Chemistry between the two leads, as a result, was lacking. As Liù, Heather Engebretson, a petite woman in the early years of what should be an admirable career, sang with remarkable purity, though marshalling her resources to push through Puccini’s heavy orchestra remained a challenge. Luca Dall’Amico offered a nicely varnish baritone as Timur. Patrick Delcour, Xavier Rouillon, and Papuna Tchuradze presented both solid singing and good comic timing as Ping, Pang and Pong. The chorus, cleverly located along the ramparts of the stylized Forbidden City, convinced; the children’s chorus, on stage throughout the evening as part of the class learning about the tale, where well used. The orchestra could have used a bit more nuance and occasional restraint but overall created a nice sonic environment. This production was a charming, warm, and inventive interpretation of 2/3 of Puccini’s masterpiece. Cura produced the most magical solution one can imagine to end the shortened evening but the constraints imposed on him denied the audience the sense of fulfillment and joy Puccini wanted us to experience: the redeeming power of love so deep, so true, so strong that death cannot diminish it. It left us wondering what Cura could have done had he been given the opportunity to stage the complete opera. Hopefully we will find out someday.

|

|

BravoCura Random Musings on Turandot

The use of the children’s chorus as part of the production was inspired and deserves to be highlighted for the creative use these young singers; however, they remained on the edge of the stage throughout the evening and for much of the time obscured sight-lines for a swathe of the audience. As a result, there were moments of disembodied singing from the primary cast and, after Liù’s suicide, many saw only Timur and Calaf grieving over an invisible body. Perhaps a different configuration would have mitigated the issue. *** Lighting was both impressive and overwhelming. Whenever Turandot was on stage, pure, brilliant white light was focused on her, the reflection off of her white outfits leaching the color out of everything else on stage, including the other characters. The concept was good—who could resist such a presence—but perhaps, in the interest of better visuals and truer colors, the white light could have been gradually toned down as Turandot thaws and wavers during the evening. *** Certainly the stage design was in place before anyone realized how tiny Heather Engebretson was (right before the start of Act II, we watched as she gleefully slide between the bars in her cell, her slight body fitting through with room to spare), but her small stature coupled with her being confined in the pits for much of the opera minimized her presence and resulted in her being nearly invisible. Liù is a secondary role to begin with, thrust out of the shadows by Timur in Act I and then returning to those shadows for much of the rest of the work; anything that further obscures her becomes problematic. There is always the danger in this role, regardless of where staged, that Liù won’t be present enough, won’t cast a big enough personality, to justify audience sympathy when dies; in this case the dangers were realized. Finding a way to remain present is just one of those things young artists need to learn as they move forward in their careers. Hopefully, Engebretson gained insight from watching José Cura. Even if he magically shrank to 4 foot, he would still command the stage because he has learned the process of self-projection, of sucking up the energy that comes from the stage itself and concentrating it before sending it out toward the audience.*** Calaf was better without the ponytail. *** Many see Turandot as a bleak and unwieldy opera with such an enormous emotional ‘punch’ with the death of the beloved Liù that it is unable to recover. The completion of Act III by Franco Alfano following Puccini’s outline allows the opera to end as Puccini wanted it to end, with the banishing of darkness, the dawning of a new age, and the triumph of love over death--but with an unfortunately weak start. The exquisite balance of Puccini design, the universality of his themes, the eternal conflict of man and woman and the healing power of love remain relatively intact, less artfully rendered; Liù’s death was a necessary parallel to the death of the Prince of Persia. an essential act that moves concept of love from abstract to real for Turandot, but Alfano fails to allow sufficient time to mourn the loss or to capitalize on its impact. After so many male deaths, a female death is required to break Turandot, to allow her to accept her humanity and embrace love; the yin and yang, the male and female, the Prince and the slave girl, completes the cycle. Liù’s death allows for the exorcism of Princess Lo-u-Ling and sets Turandot free. Puccini would have found a way to convey this transition; Alfano, alas, could not. *** Some fault the character of Calaf as being too arrogant, too selfish, too much like Turandot in his single-minded pursuit of goals. Those who think of Calaf as a cad don’t understand Puccini’s relationship with his male heroes--if these men have weaknesses, they are noble weaknesses. To a certain extent, they are the men Puccini wanted to be: strong, honorable, willing to die for what they believed in, motivated by a love so strong nothing could break it. Some blame for the misunderstanding is clearly sourced to Alfano’s too quick transition, which doesn't allow Calaf time to to grieve adequately for Liù before moving forward with Turandot. That wasn’t in keeping with the character Puccini wrote: from the beginning his Calaf was a compassionate man who fully embraced Liù as an equal and treated her with the same respect he gave his father. When he offered Turandot his riddle, it wasn’t because he was a master manipulator attempting to further humiliate her but because he was genuinely moved by her distress and because, in deference to her tale of Lo-u-Ling, he wanted to let her know he would not use brute force against her. Some productions feature a Nessun dorma sung in anger or swagger but in context it is primarily an expression of joy and optimism at besting fate—Calaf has reclaimed his destiny, reunited with his father, and found love. This is a man who has finally found his way out of darkness and no matter what happens he will have won. When Liù and Timur are brought in before Turandot in Act III, Puccini’s written instruction is that Calaf sets himself in front of Liù to protect her. When he ‘allows’ Liù to die, he is fully restrained; instead he gambles that they can survive until dawn if only they keep the secret. Some odern interpretations feature Calaf signaling his victory over Turandot with a physical assault; that would be totally out of character, as is the idea that any woman who feared rape her entire life would suddenly embrace the man who raped her ludicrous, but even more fundamental is the idea of rape is so outside the universe of Puccini that including it undermines everything he believed in. Calaf is a true Puccini hero, a transforming agent who guides Turandot away from the blackness and into the light through courage, kindness, generosity, and honor. He is Puccini’s final hero, representing Puccini’s constant belief in the power of love. He is a great invention. *** As usually portrayed, Turandot is a much more problematic character than Calaf because all we know of her is contained in exposition and in her In questa reggia. Until the final act, she doesn't interact with any other character directly; she is a cipher. In Liège, director Cura made an effort to humanize her by building a connection between the Princess and the Prince in the opening scene and again in Act II when Turandot physically reaches out to Calaf (a beautiful moment) but far too often Turandot is denied any human element, making her transition at the end of Act III somewhat improbable. There are, however, snippets of humanity in Act II that can be emphasized, such when Calaf falters on the final answer and Turandot offers a suggestion that helps him. Certainly her emotional breakdown at the end of the Act II signals the change to come, as does her reaction to Liù’s death (at least in Liège). *** What weakens Turandot is the abrupt change in tone after the death of Liù. If some enterprising composer/director/tenor (hint) were to step into the mix and write a better transitional scene—add five minutes more of music, for example—which better portrays the emotional aftermath of Liù’s suicide, the opera would be the better for it. *** So many people want to hate Turandot because of its blackness but in many ways it seems to be Puccini’s most optimistic and forward looking work. It is allegory based on an ancient tale, pitting one man against a seemingly unstoppable and powerful force. The ending, with Turandot repeating Liù’s name for Calaf, is a fitting end to the nightmare that ensnared too many.

|

|

|

.jpg)

.jpg)